2046.

From DB:

We don’t have to think of film as an art form. A historian can treat a movie as a document of its time and place. A war buff could scrutinize Eastwood’s Iwo Jima movies for their accuracy, and a chess expert could sieve through Looking for Bobby Fischer to discover, move by move, what matches were dramatized. But most of the time we assume that cinema is an art of some sort.

Not necessarily high art. Cinema is often a popular art, or in Noël Carroll’s phrase, a mass art [1]. From this angle, there’s no split between art and entertainment. Popular songs are undeniably music, and best-selling novels are instances of literature. Similarly, megaplex movies are as much a part of the art of film as are the most esoteric experiments. Whether those movies, or the experiments, are good cinema is another story, but cinema they remain.

So, at least, is our position in Film Art: An Introduction. We draw our examples from documentaries, animated films, avant-garde films, mainstream entertainment vehicles, and films aimed at narrower audiences. In other writing, Kristin has done research on high-art movements like German Expressionism and Soviet Montage (she wrote her dissertation on Ivan the Terrible), but she’s also written about popular cinema from Doug Fairbanks to The Lord of the Rings. I’ve indulged my admiration for Hou and Dreyer but also I’ve tried to tease out the aesthetics of Hong Kong action pictures and contemporary Hollywood blockbusters. Ozu gives us the best of both worlds: one of cinema’s most accomplished artists, he was also a popular commercial filmmaker.

Still, people who look upon cinema as an art don’t necessarily share the same conceptions of what kind of art it is. We have different conceptions of cinema’s artistic dimensions, and we won’t find unanimity of opinion among filmmakers, critics, academics, or audiences.

When we study film theory, this sort of question comes to the fore, and so today’s blog will be a bit more theoretical than most. Don’t let that scare you off, though; I’m trying for clarity, not murk.

Dimensions

People have tended to think of cinema as an art by means of rough analogies to the other arts. After all, film came along at a point when virtually all the other arts had been around for milennia. It’s commonly said that film is the only artform whose historical origins we can determine. So it’s been natural for people to compare this new medium with older arts.

Here are the dimensions that come to my mind:

*Film is a photographic art.

*Film is a narrative art.

*Film is a performing art.

*Film is a pictorial art.

*Film is an audiovisual art.

Let me say off the bat that I think that film is a synthetic medium, in the sense that all these features and more can be found in it. It’s like opera, which is at once narrative, performative, musical, and even pictorial. I mark out these dimensions simply to show some emphases in people’s thinking about cinema. As we’ll see, these ideas can be mixed together in various ways.

Film as a photographic art.

La petite fille et son chat (1900).

For many early filmmakers, such as the Lumière brothers (above), cinema was a means of capturing reality, documenting the visible world. Movies were moving photographs. Naturally, this conception of cinema leads us to treat documentary as the central mode of filmmaking.

It’s an appealing idea. G.W. Bush reading “My Pet Goat” wouldn’t be as revelatory presented as a painting or a theatre performance. On film we can see the event as it occurred and judge it as if we were in the same room. Even in fictional cinema, you can argue, the physicality of the actors, the tangibility of the setting, and the details–a train’s pistons, wind rustling through grass–could not be rendered, or even imagined, so powerfully in a non-photographic medium. In addition, consider Jackie Chan. His stunts are astonishing partly because we know he really did them and the camera photographed them. In an animated film, or a CGI-based one, a character’s acrobatics or brushes with death aren’t so thrilling.

The great film theorist André Bazin claimed that cinema’s photographic basis made it very different from the more traditional arts. By recording the world in all its immediacy, giving us slices of actual space and true duration, film puts us in a position to discover our link to primordial experience. Other arts rely on conventions, Bazin thought, but cinema goes beyond convention to reacquaint us with the concrete reality that surrounds us but that we seldom notice.

I think that Bazin’s idea lies behind our sense that long takes and a static camera are putting us in touch with reality and inviting us to notice details that we usually overlook in everyday life. (I try out this line of argument in relation to the tactility of Sátántangó here [2].) Moreover, you can argue that in treating cinema as a photographic art the filmmaker surrenders a degree of control over what we see and how we see it. Bazin made this claim about the Italian neorealists and Jean Renoir: creation becomes a matter of an existential collaboration between humans and the concrete world around us.

An example I used in my book Figures Traced in Light pertains to a moment in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Summer at Grandfather’s, when a tiny toy fan falls between railroad tracks as a locomotive roars past. The fan’s blades stop, then spin in the opposite direction as the train thunders over it. The blades reverse again when the train has gone. (This detail might not be visible on video.) Did Hou know how the fan would behave? Isn’t it just as likely he simply discovered it after the fact, making his shot a kind of experiment in the behavior of things? Conceived as a species of photography, cinema can yield visual discoveries that no other art can.

Interestingly, cinema didn’t have to be photographic. Many early experiments with moving images were made with strips of drawings, such as the Belgian Émile Reynaud’s Praxinoscope. You can argue that recording glimpses of the world photographically simply proved to be the easiest way to obtain a long string of slightly different images that could generate the illusion of movement. Some filmmakers, such as George Lucas, hold that filmmakers are no longer tied to photography, and that the digital revolution will allow cinema to finally realize itself as a painterly art. More on that below.

Film as a narrative art.

Rope.

This is at the core of Hollywood’s explicit concerns. Producers, directors, crew, and of course screenwriters will agree that Without a good story, the movie fails. Our Indie and Indiewood filmmakers say they’re trying to find fresh stories, the ones that “haven’t been told yet.” Overseas filmmakers dominated by Hollywood tell us, “We have our own stories to tell.” Even the most celebrated arthouse filmmakers often say they’re interested in character as revealed through action. Resnais, Rivette, Fassbinder, Haneke, and all the rest may have told unusual stories, but still they told ’em.

Likewise, many viewers will say that they go to the movies to experience a story. Reviewers online and in the popular press, if they do nothing else, are obliged to sketch out the film’s plot, though they mustn’t give away the ending. Even in academia, most discussions of films focus on what happens in the narrative.

When we consider film genres, we’re usually concentrating on the narrative aspects of them. Most genres display typical characters and plot patterns. The backstage musical features aging stars and young hopefuls, caught up in the process of putting on a show. The horror film typically centers on a monster’s attack on humans, who must fight back. One type of science fiction shows us an overweening scientist striving to go beyond “what is proper for humans to know.” Both fans and scholars discuss other aspects of genre films, but narrative is often central to their concerns.

Historians have traced in great detail how filmmakers employed cinema as a narrative art, but we’re making more discoveries all the time. How, for instance, have films signaled flashbacks? How do they let us know we’re in a character’s mind, or attached to his or her optical point of view? How have they structured their plots? Can we pick out distinct approaches to narrative–in various periods, or genres, or national cinemas? How have narrative conventions changed over the years? Some of the answers Kristin and I have proposed can be found elsewhere on this site, and in our books and articles.

Film as a performing art.

The Marrying Kind.

In the West, since Plato and Aristotle we’ve distinguished between verbal storytelling and dramatic presentation, or performance. Films may be stories, but they’re not exactly told: they’re enacted. At Oscar time, we’re especially conscious of this analogy, for the Actor/ Actress nominees usually garner the most public attention.

Hollywood acknowledged cinema as a performing art in the 1910s, when it created the star system. The Star reminds us that film acting isn’t exactly the same as theatre acting, since an elusive charisma puts the performance across. John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Keanu Reeves, and many other “axioms of the cinema” aren’t good actors by stagebound standards, but once they show up on screen, you can’t take your eyes off them. This notion intersects with the photographic premise: we say that the camera seems to love them.

You can argue that Andy Warhol revamped this idea. His superstars weren’t photogenic by ordinary standards but their almost clinical narcissism and exhibitionism, captured by the camera, made them as mesmerizing as any matinee idols. Warhol films like Paul Swann create rather disturbing emotions by putting us in the presence of an awkward performer.

Reviewers place a premium on a movie’s performance dimension. After they’ve told us a bit of the plot , they appraise the job the actors did. Some ambitious critics have written wonderful appreciative essays on acting, as in Andrew Sarris’s “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet” [3] and the collection [4] OK You Mugs. See also the two collections of articles by Gary Giddins, which I discuss in an earlier blog [5].

Academic film studies has been slow to study acting systematically, partly because of a bias against considering cinema as a theatrical art, and partly because acting is very hard to analyze. But Charles Affron [6], Jim Naremore [7], Roberta Pearson [8], and Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs [9] have greatly helped us understand performance practices. They show, among other things, that it isn’t just a matter of the face or the voice: a fluttered hand or a willowy stance can be as powerful as a frown or a line reading.

Film as a pictorial art.

Ohayu (Good Morning).

Progressive opinion in the silent era tended to deny that film was a performing art, since that would make it a form of theatre. No, film had unique capacities. Cinema was essentially moving pictures.

It was a visual art that unfolded in time, so a movie was neither quite the same as a painting (frozen in time) or as a stage play (not pictures but three-dimensional reality). The coming of sound somewhat reduced the appeal of this line of argument, but to a very great extent, students of film technique still emphasize cinema as a visual art.

Theorists argued that the film frame was a pictorial field, not a proscenium stage. Action unfolded in the frame in ways that dynamized space. The choice of angle, camera distance, camera movement, and the like created a visual fluidity that had no equivalent on stage or in other graphic arts. Even cinematic staging was quite different from blocking in a theatrical space. Add to this the ability to join one strip of pictures to another via editing, and we have a unique pictorial artform.

The theorists of the silent era, like Rudolf Arnheim and the Russian montagists, gave us a vocabulary and an orientation to studying visual style, but their legacy hasn’t been fully developed. Journalistic reviewers typically don’t pay that much attention to the way movies look. Nor, surprisingly, do academics. Film studies departments seldom pursue research into visual style and structure.

Here the professors are out of sync with the people whose work they study. Manuals and film schools teach composition, lighting, cutting, camera placement and the like. Professional filmmakers all over the world often think in pictures; they prepare shot lists and storyboards and care very much about the color values and editing patterns of the finished work. We can see their interest in visuals in DVD commentaries and supplements, and as viewers start to absorb bonus materials, perhaps their interest will be whetted too.

Needless to say, a number of avant-garde filmmakers, from Viking Eggeling and Walter Ruttmann to Deren, Brakhage, Ernie Gehr, James Benning, and Nathaniel Dorsky, have also thought of cinema as having the power to refresh, even redeem, our vision. But many of the most important directors aiming at broader audiences are also renowned for their visual styles. To mention just a few: Griffith, Feuillade, Sjostrom, Keaton, De Mille, Murnau, Lang, Dreyer, Lubitsch, and Dovzhenko; Ford, Hitchcock, and von Sternberg; Renoir, Ozu (above), Mizoguchi, and Ophuls; early Bergman, Antonioni, Jancsó, Resnais, Angelopoulos, Tarr, Tarkovsky, Kieślowski, Kiarostami, and Makhmalbaf; Scorsese, Spielberg, Michael Mann, and Tim Burton. Some, like Oshima, Sokurov, and Johnnie To, have been polystylistic, exploring many different visual pathways.

Film as an audiovisual art.

In the 1920s, many theorists feared the coming of synchronized sound, since that would thrust film back toward theatre. The “talkies” would sacrifice visual artistry to Broadway dialogue. This worry was mistaken, but I can sympathize. Probably the mandatory silence of early film pushed filmmakers to find means of visual expression. Would we have Chaplin and the other clowns if they could have spoken at the start?

Yet a great deal of sound cinema wasn’t canned theatre. Film became a synthetic medium blending imagery, the spoken word, sound effects, and music into something that was neither painting nor theatre nor illustrated radio.

Though he’s thought of as the premiere theorist of editing, Eisenstein actually developed this idea of audio-visual synthesis. He was fascinated by the ways in which images and music worked together, creating an idea or feeling that couldn’t be expressed by either one. If shot A followed by shot B gave us something that wasn’t present in either one, then why couldn’t shot A and sound B yield the same results? He believed that Disney’s 1930s films [10] were the strongest efforts in this direction, as when a peacock fanned out his tail to a rippling melody. Eisenstein called it “synchronization of senses.”

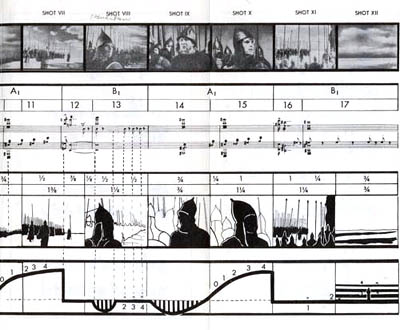

Eisenstein sometimes pushed this idea pretty far. His remarkable analysis of one sequence in Alexander Nevsky (sample above) tried to show how the movement of the viewer’s eye across a suite of shots actually mimicked the movement of the music. He made the case tough for himself because the shots contain almost no movement within them: Eisenstein claimed that we read the compositions from left to right, in time with the musical chords!

Not only Disney but many filmmakers of the 1930s experimented with audiovisual fusion–Kozintsev and Trauberg in Alone, Pudovkin in Deserter, Mamoulian in Love Me Tonight, Renoir in the final danse macabre of Rules of the Game, and Busby Berkeley’s Warners and MGM musicals. Welles made Citizen Kane a feast of audio-visual echoes, as when the wobbly descent of Susan’s singing voice is matched by the flickering of a stage light that finally goes out.

With magnetic and multichannel recording in the 1940s and 1950s, filmmakers could compose very complex sound mixes, and later improvements offered still more possibilities. After Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, we expected a movie to be an immersive audiovisual experience, like the light show at a rock concert. Scorsese, especially in Raging Bull and Goodfellas, created powerful mergers of music, sound effects, camera movement, and character movement. So did the Hong Kong kung-fu films of the 1970s and early 1980s. The spellbinding languor of Wong Kar-wai’s films stems largely, I think, from their synchronization of color, slow motion, drifting camerawork, and evocative music.

The avant-garde has pursued more elusive synchronizations of sense modes.The idea of synthesis was floated in the silent era, when experimenters like Oskar Fischinger used musical pieces to anchor their abstract imagery. This tendency has resurfaced in music videos, some of which (Michel Gondry’s in particular) have clear links to the experimental tradition. So too do the shorts and features of Peter Greenaway, especially in his collaborations with composer Michael Nyman. In a film like Prospero’s Books, Greenaway seems to follow Eisenstein in imagining a Wagnerian synthesis of writing, image, and sound.

By contrast, Godard explores all manner of unpredictable junctures between image and sound, with the tracks teasing us but always avoiding a complete coordination. Somewhat similar are the disjunctive image/sound juxtapositions in Peter Kubelka’s Unsere Afrikareise and Bruce Connor’s Report, or the inverse and retrograde organizations of Structural Film soundtracks like Michael Snow’s Wavelength and J. J. Murphy’s Print Generation.

Film academics have begun to analyze image/ sound juxtapositions, studying the development of early talkies and more recent Dolby technology. Arguably, film researchers now pay more attention to music than they pay to imagery. By contrast, most journalistic critics ignore a film’s soundtrack, except occasionally to comment on line readings and pop tunes. As for ordinary audiences, perhaps DVD and home theatre technology have made people more aware of how movies can saturate our senses with audiovisual correspondences.

Three waivers

1. Once I floated these distinctions in a seminar discussion, and a participant mentioned that cinema was also an emotional art. I’d agree that a lot of cinema aims at arousing feelings, but this idea can be found in all the dimensions I traced. Each conception of film favors different means of stirring up emotion.

For example, the photographic approach holds that recording and revealing the world is the most effective way to move spectators, while the narrative approach favors stories as the means to that end. The performance-based approach trusts that we’ll react empathetically to the emotional states displayed by our fellow humans, but the visual-art approach says that cinema can arouse feeling by manipulating pictures in time and space, perhaps even pictures that don’t show any people at all. Eisenstein argued that synchronization of senses was the most powerful form of emotional stimulation, creating in the viewer an “ecstasy” comparable to religious fervor. Beyond these general considerations, it would be worthwhile to tease out the different sorts of emotion that each perspective tends to emphasize.

2. Someone else might ask: What about other analogies? Filmmakers and critics have sometimes compared cinema to music or poetry. Shouldn’t those arts be added to the list?

I think that these comparisons show up principally within the broad idea of film as a pictorial art. The French Impressionist directors of the silent era thought that they were making “visual music,” and Brakhage and Deren’s conceptions of the “film lyric” were mainly pictorial. (See girishshambu [11] for thoughts on the latter.) I’d suggest that filmmakers in the pictorial-art camp have looked to these adjacent arts for models of patterning (meter, rhythm, motif development) and imagery (metaphor and subjective states in lyric verse). Filmmakers are also attracted to the idea that music and poetry tend to be suggestive rather than explicit, conveying powerful feelings in elusive and open-ended ways.

Polemically, filmmakers often conjure up these musical and literary analogies to counter the mainstream cinema’s emphasis on narrative and performance. If we think of film as lyric or rhapsody, story seems less important. The same thing goes, I think, for thinking of film as moving architecture or kinetic sculpture; the analogy again targets film’s pictorial dimension and its non-narrative potential.

3. To think of film as having an affinity with another art form isn’t to say that they’re identical. Thinking of cinema as a performance-based art, for example, doesn’t commit you to saying that film acting is the same as theatrical acting. Instead, thinking along these lines seems to create a first approximation, an initial comparison that lets you move on to notice differences. Once you consider film as a pictorial art, you can then ask in what ways it differs from other pictorial arts, or in what ways this particular movie transforms or reworks the techniques of painting. Ballet Mécanique, which we analyze in Film Art (pp. 358-366), owes a lot to cubism, but its imagery isn’t identical to what Picasso, Braque, and Gris came up with on canvas. All of these analogies seem to work best as frameworks for sensitizing us to both similarities and differences between film and other arts.

And . . . so?

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.

Each conception of film art harbors a good portion of truth. Each may fail to cover all of cinema, but for certain types of film, or particular movies, some are likely to be more helpful than others.

For example, it’s useful to consider David Lynch as making audiovisual works, in which blinking lights or grooves in pine planks seem uncannily synchronized with throbs and hums and Julee Cruise vibrato. Very often story and acting seem to precipitate out of an enveloping pictorial/auditory atmosphere. This isn’t to say that you couldn’t study narrative or performance in Lynch films; it’s just that taking up the audiovisual-mix perspective will throw certain aspects into sharper relief.

You could also argue that the Hollywood studio era blended many of these appeals into a single strong tradition. Story was important, but so was performance. Visual style was often striking, but so too was an expressive soundtrack that went beyond simply recording the dialogue. Sound effects, musical scores, and verbal hooks between scenes created imaginative resonances with the image track. Contrariwise, we can see some avant-garde traditions as taking a purist tack. In several of his films, Brakhage reduces narrative, purges performance, and bans sound: we have to engage wholly and solely with a pictorial experience.

Just as we can distinguish film traditions along these dimensions, we can contrast writers and thinkers. Some critics are very good in pinning down performance qualities, others excel at plot dissection or visual analysis. Arnheim is sensitive to pictorial values but he has little to contribute to understanding storytelling.

Bazin and Eisenstein are attuned to several of the dimensions I’ve traced out. Bazin’s interest in cinema’s photographic basis also alerted him to pictorial possibilities, like deep-focus and camera movement. Eisenstein, famous for his ideas on cinema’s visual dimension, was as I’ve said interested in sound as well. He was no less concerned with film performance, which he conceived as expressive movement (to be synchronized with properties of the image and the soundtrack). But he voiced almost no interest in narrative or photography.

I warned you that this blog would be theoretical, but I hope the takeaway message is clear. Cinema is teeming with artistic possibilities, and each of these frameworks can illuminate certain areas of choice and control. We don’t need to pick a single creed to live by, but we deepen our understanding of film by being sensitive to as many as we can manage.