Little Women (2019).

DB here:

For a while The Blog conducted an annual ritual of analyzing storytelling techniques in year-end releases. I wrote entries from early in 2016 [2], in 2017 [3], and in 2018 [4]. Last year I muffed it, largely because of time spent revising our Christopher Nolan book [5]. (Yes, we’re also looking forward to Tenet, especially after that hellah trailer [6].)

This time I’m trying an alternative. Instead of surveying a range of releases, I’ll focus on two that I think encapsulate some robust variants on familiar narrative strategies. Those strategies include choice of protagonist, linearity versus nonlinearity in time, and manipulation of viewpoint. While I’m concentrating on Marriage Story and Little Women, I’ll draw out some comparisons with other films.

Many spoilers follow, but of course you’ve probably seen all the new films. Except maybe Cats.

Protagonists, dual and dueling

Human nature is not given to a protagonist/antagonist three-act structure. Human nature is just one damn thing after another in which the only thing that matters is what went on today because yesterday is gone. And that is contrary to a lot of the business that we’re in, which makes sure that everybody understands the story by page 30 and is involved in the conflict.

Tom Hanks [8]

You’re plotting a film. What sort of options do you face? A basic choice involves protagonists.

You might build the film around one character who pursues a cluster of goals. Examples this season would include Dark Waters, Motherless Brooklyn, Uncut Gems, and Harriet. The protagonist can have helpers, and will certainly have adversaries, but her or his initiatives, decisions, and responses propel the action. In addition, we’re usually attached to the protagonist’s point of view, which limits us to what she or he knows. Judicious widening of the horizon often takes place to enhance tension. In Uncut Gems we’re briefly attached to Arno’s thugs when they’re tailing Howard, and the climax crosscuts Howard in his office with Julia placing his big bet.

You could center the action on two characters, giving us a dual-protagonist plot. Here the goals may be shared or at least compatible. In The Aeronauts, a lady balloonist and a male meteorologist cooperate, with frictions, to break ascension records, while Ford v. Ferrari unites two men working together to win at Le Mans.

More rarely, a dual-protagonist plot can shift the protagonist in the course of the action. Good examples are Red River (1948) and The Killers (1946). I’d argue that Don Corleone functions as protagonist in the early sections of The Godfather (1972), while Michael takes up that role later. Similarly, Waves initially concentrates on Tyler, but he largely drops out of the plot and his sister Emily drives the film’s second half.

Alternatively, the plot can present two protagonists in competition. This season we’ve had The Current War, centering on the struggle between Edison and Morgan to transmit electrical power. The narrational weight is largely with Edison, but I think Morgan is characterized enough and we’re attached to his viewpoint frequently enough to present a counterweight. Morgan isn’t simply an antagonist but rather what Kristin calls a parallel protagonist, like Salieri in Amadeus or Captain Ramius in The Hunt for Red October. As these examples indicate, parallel protagonists, although they’re trying to figure out each one’s aims and stratagems, often become fascinated with each other and recognize their affinities.

Paired protagonists are common in romantic comedies, which often consist of friction between the couple (due to clashing goals) but end in harmony and union. What’s striking about Marriage Story is that here the end, not the start, of a romantic alliance is treated through the dual-protagonist strategy. Charlie and Nicole struggle over the terms of their divorce, particularly the handling of custody of their son Henry. Unlike Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), which is organized chiefly around the husband’s viewpoint, this gives weight to both spouses.

Director Noah Baumbach achieves this balance through a cunning parallel block construction. The film opens with two montages of roughly equal running time. One surveys Nicole’s habits and accomplishments with Charlie’s voice-over praising her. (“She’s my favorite actress.”) Then we get a montage illustrating what Nicole loves about Charlie, with other incidents stitched together by her voice-over. Both montages weave in scenes of Nicole in rehearsal while Charlie, the director, makes suggestions.

Baumbach has compared these montages to an overture in musical theatre. The film’s score sets out themes associated with each protagonist, and the quirks and routines that rush by establish important motifs, like haircutting, Monopoly games, and Henry’s urge to sleep with his parents. With the he said/she said duality, the montages prepare us for the film’s strategy of parallelism, a compare-and-contrast attitude.

The montages are revealed as visualizations of two memoirs the couple have written for a mediator.

They’re planning to divorce, and he’s asked them to recall what they loved about each other. Charlie is willing to share his notes with Nicole, but Nicole won’t show hers. This hints that he’s more reluctant to separate than she is, planting a question about why she seems determined to pursue the divorce.

Just as important, we’ve been given privileged access to both characters’ minds, and this sort of alternating omniscience will proceed throughout the film. There won’t be any more plunges this deep into subjectivity, but we’ll always know more than either does, because after they separate we’ll be attached to one or the other in large stretches.

For a time, though, we’re with both. In the mediator’s office, and then during the play’s performance, in the bar with the troupe after the show, and in the family apartment, they interact as a couple. (True, Charlie sleeps on the sofa.) But once Nicole moves to California, the first block of action ends and we are attached to her and Henry as she launches her new project, a TV pilot.

Not until Charlie comes to visit Nicole, her mother, and her sister does the narration bring him back. There he’s officially served the divorce papers. This scene launches a discreet viewpoint pivot from her to him. The family cuddle ends when Henry banishes Charlie from bed, foreshadowing how marginal his father will be to him from now on.

The film’s next block attaches us to Charlie as he seeks out a lawyer, takes Henry on outings, and clashes with Nicole about how to celebrate Halloween. The couple wind up giving Henry two trick-or-treating trips, in different costumes, which reiterates the duplex structure of action we’ve been presented with since the start.

The alternation between Nicole and Charlie’s viewpoints quickens as their negotiations get more fraught. Their first legal meeting ends with Charlie’s losing faith in his easygoing attorney. The next meeting is an escalating confrontation between Charlie’s new hard-charging lawyer and Nicole’s equally tough Nora. In the courtroom exchange, the he said/she said pattern becomes vicious as each lawyer weaponizes minor incidents from scenes we’ve seen to cast shame on the opposing side.

The nastiness of the custody battle comes to a crisis in a ten-minute duologue in Charlie’s apartment, an all-out fight between Nicole and Charlie. They run through a repertoire of reactions, from assurance of mutual admiration to declarations of annoyance, unhappiness, frustration, and complaints. By the end they’re screaming insults. Charlie rages and then, as if aware of how monstrous he’s being, collapses sobbing at Nicole’s feet.

Most classically constructed films follow the pattern Kristin identified back when. [19] The plot consists of a setup, a complicating action redefining the setup, a development section consisting largely of delay and backstory, and a climax that resolves the situation. An epilogue asserts a stable, if changed state of affairs. The four main parts are roughly equal in running time, with the climax tending to be a bit shorter and the epilogue being only a few minutes.

Up to a point, Marriage Story conforms to this architecture. The first thirty minutes set up the split in the family before focusing on Nicole’s new life in California. Both Charlie and Nicole had hoped to separate amicably, with no need for lawyers. But thirty minutes in Nicole hires Nora and sets in motion a more severe legal battle than the couple had expected. The complicating action is triggered by serving Charlie the divorce papers.

There’s no turning back, and the new situation centers on figuring out how to handle access to Henry. Charlie wants Henry to spend time in New York (“We’re a New York family”) but Nicole wants him with her, and as he was born in California the law inclines to her side. Hence the triple thrust of the Charlie block: visiting lawyers, trying to keep his Broadway production on track, and winning some loyalty from Henry.

The development section consists of characterizing stretches (Nicole indulges in a quick sexual encounter) and delays: the unsatisfactory first lawyer session, a power outage at Nicole’s house, and the courtroom showdown. What happens next, though, seems to me quite original.

Between theatre and TV

To determine custody, both Nicole and Charlie must let an evaluator visit to observe each one’s treatment of Henry. In a more ordinary film, this stretch would initiate the climax. The visit from the evaluator would furnish a deadline for determining how custody would be handled. Then the film’s peak could be the vicious, trembling argument between Charlie and Nicole. This would be the explosion that reveals both their love and the impossibility of their staying together.

From this angle, Charlie’s guilt-ridden collapse would be the resolution–his realization of how he stunted Nicole’s life. A courtroom finale settling the terms of custody (a little more for Nicole than Charlie) would fill out the climax and lead to an epilogue, perhaps on the courthouse steps.

Excuse me for rewriting the film. I do it to show that Baumbach’s script does something daring. The big argument comes before the evaluator’s testing. After that brutal clash, we see Nicole rehearsing her answers in Nora’s office. Moreover, the blundering efforts of Charlie to convince the stiff evaluator he’s a good father play out in a lengthy comic scene with some gory sight gags.

A certain amount of suspense remains, I think, but the final cascade of gags works against the emotional pitch of the couple’s quarrel. Baumbach has, in effect, risked using an anticlimax to round out the normal climax section of the film. It also serves as a good-natured punishment for Charlie’s self-centeredness.

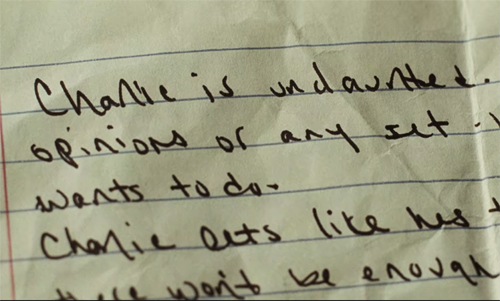

The same daring informs an unusually lengthy epilogue. It’s built out of the sort of modules we’ve seen already. Nicole and her friends and family celebrate her divorce with a party, while Charlie mopes around Manhattan and morosely salutes his play’s closing with his troupe in a bar. We might stop there, but Baumbach again does something original (though highly motivated). Charlie, now relocated for a teaching gig in LA, comes to pick up Henry and discovers the boy reading the note about Charlie that Nicole had prepared for the mediator session.

Not only does it reveal the feelings she had suppressed during the session, but the fact that she kept it shows she still harbors affection for that part of her life. Other films surprise us in the epilogue (Citizen Kane, for instance), but Baumbach’s use of the memoir in the film’s final moments remains a pretty bold, and moving, choice. This stretched and packed epilogue shows Charlie how much Nicole loved him, while also suggesting things that contributed to stifling her. Lines like “He’s very competitive” and “He loves being a dad” have a new impact now that we’ve seen his battle for his son.

In telling this story, Baumbach exploits a larger strategy of what theatre people call continuous exposition. Instead of giving the necessary backstory in a lump at the beginning or middle, major information is sprinkled through the ongoing plot. We’re familiar with this device in films that trigger fragmentary flashbacks, filling in backstory bit by bit. Baumbach goes with a more “theatrical” strategy using dialogue to invoke things that happened before the first scenes..

One of the major instances involves Nicole, who breaks down in an embrace with Nora, sobbing that Charlie slept with his assistant. Coming half an hour into the movie, it explains Nicole’s bitterness in the mediation session, as well as her larger reappraisal of her life with Charlie. At other points we learn of big events, like Nicole’s show taking off and Charlie’s long-term settling in LA, in casual conversation, not in extended scenes.

Crucially, in their climactic quarrel, Charlie justifies his affair by accusing Nicole of withholding sex for a year. We can’t appraise the truth of this, but it at least fills in a motive that more conventional exposition would have put into the setup. Resisting the temptation to supply flashbacks for all these revelations, Baumbach trusts our memory. That way the new data can color our ongoing understanding of the characters. The opening montages were generous but one-sided, chunks of incomplete exposition that suppressed important motives and behavior.

Continuous exposition is associated with Ibsen and playwrights who followed, but the theatrical patron hovering over the film is Stephen Sondheim. Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird had used Sondheim as a touchstone for ambitious high-school players, but the parallel structure of Marriage Story makes more explicit references, this time to Sondheim’s Company. Nicole’s party features her and her mother and sister performing “You Could Drive a Person Crazy,” a saucy song about dumping a weak man. Soon in the bar Charlie is singing the yearning “Being Alive.”

Maybe a little on the nose (like the movie’s title), these citations seem true to the tastes of these show-biz mavens, while suggesting that at least some of Manhattan clings to Nicole in her exile.

Another parallel reminds us of a perennial Hollywood motif. Nicole began her career in a raunchy teen movie but thanks to Charlie’s stage shows she became a respected performer. Yet to establish her own identity more fully she agrees to shoot a TV pilot. Marriage Story positions itself between theatre (a little pretentious, but nobly struggling) and TV (dumb and superficial, but high-tech and well-financed). Worse, TV literally defaces Nicole.

Theatre, TV: what about film?

In this story about show-biz LA, movies and references to them are sparse. (I didn’t spot any.) So maybe we should take this film itself as standing in for righteous cinema, rather than the teenpic trash Nicole was in. Perhaps Marriage Story offers itself as its own example of the subtlety and risk-taking that cinema can embody. Even when streaming on Netflix.

Muses in the family

The family saga is one Hollywood genre that doesn’t get enough respect. We tend nowadays to celebrate the tough, not tender side of studio cinema. The cult of noir, the abundance of hard-edged action pictures, and the idolatry that trails Tarantino all tend to make us prefer force to gentleness. When families gather, we expect big trouble, if not outright murder (Knives Out). We decry weepies of any sort, and family sagas are often felt to be soft, schmaltzy, womanish. A male friend tells me that Little Women is “a movie about hugs.” When NPR devotes a whole show [30] to it, panelists ponder how to convince men to see it. No wonder the family film has migrated to daytime cable TV.

Yet the family saga is one of the nicest things American cinema does. Two of our greatest masterpieces, How Green Was My Valley (1941) and Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), are prime examples. The Forties were rich in such efforts, including Forever and a Day (1943), Life with Father (1947), I Remember Mama (1948), The Human Comedy (1943), and Since You Went Away (1944). We ought to recognize as well the strength of later entries like The Joy Luck Club (1993), How to Make an American Quilt (1995), and Soul Food (1997), all trying out some of the fresh approaches to storytelling that were emerging in the 1990s.

And the sentiments informing domestic sagas seep into other genres. The Fast and Furious team, we’re told, come to be a family, as do the Avengers. The coming-of-age story, that perennial of indie cinema, inherits the aura of cozy warmth that is central to the family saga. I’d add one of my favorites, We Bought a Zoo (2011), which isn’t really a saga but does radiate a comparable warmth.

Although there are probably earlier examples (I think of Vidor’s 1924 Wine of Youth), it seems likely that the 1933 MGM production of Little Women furnished an important template. The four March sisters, each drawn to a different art form, are a model for the musically gifted sisters in the fine Four Daughters (1938).

And surely the fact that Katrin in I Remember Mama chronicles the family’s daily lives owes a lot to the example of Jo March, aspiring novelist.

The family saga poses at least three creative problems for the filmmaker. Since each family member is likely to confront personal problems (romance, finance, school, job) how do you weave and weight multiple storylines? How do you provide conflict to propel the action? And, since the “saga” comparison suggests development over years or even generations, how do you handle long spans of time cinematically?

Greta Gerwig handles all these problems adroitly in her version of Little Women. I’m going to concentrate on the film, but I’m aware that some of the narrative strategies are taken from Louisa May Alcott’s original novel. But much of what’s ingenious about Gerwig’s adaptation is of her own devising.

Start with storylines. In most such films, the trick is to create a group but then produce a scale of emphasis running from minor figures to the most important one typically, the “first among equals.” In How Green, that is Huw, also our narrator; in Meet Me in St. Louis, it’s Esther. But the doings of other characters shape the family’s destiny and the decisions made by the spotlighted figure. So the activities intertwine.

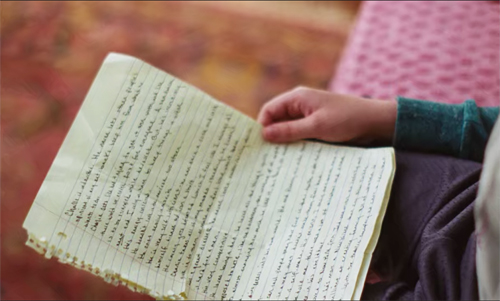

In Little Women, characters shape one another’s development. Jo, the first among equals, is nonconformist and self-reliant. Yet she needs steering–from Friedrich, the professor who tries to turn her away from sensation fiction, and more importantly from Beth, who in her sickness urges her to write “our story.” They give her the strength to persist and trust her sense of what her writing can be.

On the romance front, Jo’s rejection of Laurie’s proposal of marriage opens the field for sister Amy, who has already supplanted Jo in the role of amanuensis to Aunt March. When Jo, out of loneliness, decides to welcome Laurie’s offer, it’s too late: he’s married to Amy. The tangled alliances of melodrama get tightly bound in the family saga.

The other sisters contribute to the causal weave of the plot, with Meg’s decision to abandon the stage reinforcing Jo’s stubborn attachment to her art. More generally, the fates of the sisters dramatize the tension between creative impulse and the social demands of domesticity. Meg wants a family more than fame. Amy, the indifferent painter, can hope only for a good marriage (the same prospect Aunt March makes explicit to Jo).

In family sagas, the siblings are put in parallel. Huw’s brothers leave the household, but he loyally stays, and Rose, the mature sister, has more trouble attracting men than the vivacious Esther. Here, Jo’s kindred spirit is Beth the pianist, whose playing gives solace to Mr. Laurence in his grief. But illness keeps Beth from fulfilling herself either as artist or grown woman. As for Marmee, we’re allowed to catch a glint of Jo’s defiance behind the older woman’s warmth when she confesses that she’s angry every day.

Jo’s main contrast is with Amy. Amy has done nasty things, but she accepts the burden, laid down by Aunt March, of marrying for money, not love, in order to benefit her loved ones. She does this even though, as she reveals in a key scene, she has always loved Laurie and has always felt herself overshadowed by Jo. (Those revelations are also suggested as what leads Laurie to fall in love with her, and not simply as a substitute for Jo.) Even the various suitors get ranged along comparative dimensions of class, strength of will, and temperament.

The need to provide a dense social milieu also creates parallels–here, in terms of good deeds. The Marches are lower middle-class, living on a parson’s income, but they share their Christmas dinner with a more deprived family. The primary family is constantly compared to the wealthy Laurences, who are generous and good-hearted. Even Aunt March, who married well and embraced hardheaded principles, wills her mansion to Jo. The contrast with the flinty publishing house and the imperious Dashwood is softened when we learn, surprise, that he has a batch of daughters himself.

What about conflict in the family saga? There’s often an external threat–predatory capitalism in How Green Was My Valley, the war in The Human Comedy–but not always a personified antagonist. Often these films have no straightforward villains. Parental error can move the plot, as when in Meet Me in St. Louis Alonzo Smith announces that he’s taking a job in New York. And crises are created by misunderstandings or happenstance, most commonly illness. Somebody almost always gets hurt (here, Meg’s twisted ankle, Amy’s plunge through the ice) or sick (Beth’s scarlet fever).

By and large, the conflicts come through romance and sibling rivalry. In Little Women, Meg loves John only somewhat more than she loves fine clothes, so their impoverished marriage nags at her heart. Amy, enraged at not going to the theatre, burns Jo’s manuscripts. Jo responds with hatred–until Amy falls through the ice and needs rescuing. Amy later considers marrying a rich nonentity, and instead acknowledges her long love for Laurie–who in turn loves Jo. As in most melodramas, we know more than any one character, so we watch as characters’ hopes rise against forces they don’t yet realize.

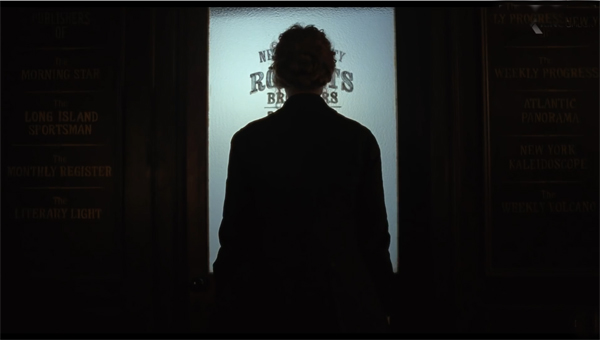

Even without a clear-cut antagonist, the family members can have goals. The March girls start out as aspiring artists, and stretches of the plot are devoted to them developing their abilities. As their goals change, swerving two of them to marriage and maternity, Jo keeps striving toward what we see her doing in the film’s very first scene: selling her stories. Her burning desire to write is a major through-line, and it encounters obstacles of many sorts, from the harrumphing Dashwood to the destruction of her manuscripts by Amy. And even Jo, as we’ve seen, recasts her goals: in offering solace to the dying Beth, she will write “all about us.”

That means writing about the family as it changes over time. Our third narrative problem, in other words.

“If I were a girl in a book, this would all be so easy”

Marriage Story‘s avoidance of flashbacks makes it unusual nowadays. It’s hard to find a movie without at least a few flashbacks. As mysteries, Motherless Brooklyn and Knives Out resort to them to replay scenes with new information. Other films make time shifts basic to their architecture. The Aeronauts uses flashbacks to supply the backstory to an unfolding crisis situation, while Hustlers switches between a contemporary interview and stages in the career of the woman questioned.

The Irishman goes for deeper embedding. The overall frame shows elderly Frank Sheeran in the care facility; the next frame is Frank’s trip with Russell Bufalino and their wives to upstate New York, where Frank will kill Hoffa. That trip in turn flashes back to the central story of Frank’s career with the mob. I try to show in Reinventing Hollywood that this sort of Russian-doll structure comes to be a major option in American film during the 1940s.

In Little Women, the years of change in the March family are given through alternating blocks. We start in the present, with Jo in New York struggling to get published. She’s summoned back to Concord because Beth is ill. Meg is living in poverty with husband John, and Amy is in Paris with Aunt March. For about eleven minutes, crosscutting carries us among the sisters.

This block of exposition is followed by a title, “7 Years Earlier,” that sets up the time oscillations we’ll get for the rest of the film. In chronological order we follow the sisters growing up. Chunks of scenes from the past, shifting viewpoint among several characters, alternate with briefer scenes of the ongoing present showing Jo’s settling back into the family. Sometimes the cuts break the blocks into smaller, interlocking bits, as when we shuttle quickly between Beth’s childhood illness and her death one year later.

Why split a linear story into two intercut strands? Flashbacks often create a specific sort of anticipation: Not just What will happen next? but What caused the outcome I already more or less know? In the first ten minutes we learn that Laurie proposed to Jo and she refused him; that Amy, not Jo, became Aunt March’s traveling companion; that Meg married John, the impoverished tutor. We’ll witness the development of all these turning points, and more. We must watch the rise and fall of characters’ hopes, knowing they will be dashed. But we also know, from Jo’s initial visit to the publishing house, that she will gain some success. This time-jumping gives us another level of omniscience, one that lets us savor the details of emotional scenes whose outcomes we roughly know. We’re in the theatre, after all, to enjoy the rapture of pathos.

Instead of tagging each time shift with a date, Gerwig expects us to keep track of the double-entry storylines. She assists us by making story motifs visual hooks between past and present. Silk for a dress, a key, Jo seen writing at a window–these link scenes but also carry dramatic weight in the ongoing action. Other echoes are longer-range. We’re invited to remember contrasting dance scenes (tavern, ballroom, porch), scorched dresses, and piano pieces.

Eventually the past scenes catch up with the present. The fusion comes with the burial of Beth and one more clutch of flashbacks, to Meg’s wedding. I take this as the end of the development section. “Childhood is over,” Jo says. Back in the present, Jo vows to abandon writing.

Now the present-time action dominates the climax. Grieving for Beth, distraught at Meg’s leaving the household, and crushed by the marriage of Laurie and Amy, Jo burns her manuscripts–except for the stories she wrote for Beth. She starts to assemble them and write more.

After a glimpse of Dashwood refusing the manuscript, we see Friedrich come to visit the Marches on his way to California. After he’s left for the station, the family claims that Jo obviously loves him.

At this point, in her most daring creative choice, Gerwig retains the crosscutting technique in a way that seems to continue the present/past alternation. Dashwood’s daughters have urged him to publish Jo’s manuscript. In New York, in a scene that rhymes with the opening passage, Jo negotiates with Dashwood.

Their conversation is intercut with views of Jo rushing to the station to catch Friedrich and ask him to stay.

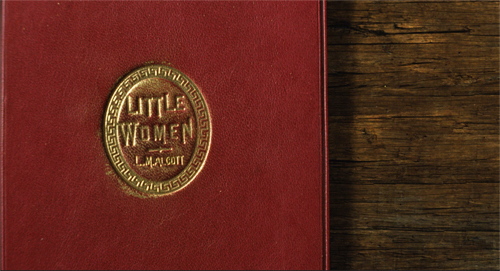

The epilogue consists of more alternations. We see Jo watching Little Women being printed, crosscut with a party at the school Jo has founded in Aunt March’s mansion. There John, Friedrich, and Laurie can be glimpsed as Meg and Amy teach children the arts they had practiced. The celebration ends with a birthday cake presented to Marmee.

But there’s another way to take the final minutes. The alternation isn’t tracking two points in time–Jo’s rush to Friedrich and a later session with Dashwood–but rather a split between fiction and reality.

We’re coaxed to take scene of Jo’s pursuit of Friedrich as representing not her own action but the changes that Dashwood demands in Jo’s novel. “Who does she marry?” he asks, explaining that a book sells only if there’s a marriage. Jo reluctantly agrees. “I suppose marriage has always been an economic proposition, even in fiction.” Cut to Jo racing to the station. After the shots of her embracing Friedrich under an umbrella, we’re back in the office. Dashwood suggests the chapter title, “Under the Umbrella,” and Jo agrees. But in turn she makes demands: “You keep your five hundred dollars and I’ll keep the copyright. . . . I want to own my own book.”

We’ve assumed throughout that Jo’s book is highly autobiographical, but we’ve taken what we see and hear as actual events, the living source of a literary text. Instead, the crosscut climax allows a parallel reality to burst forth, a road not taken. The epilogue yields another ambivalent passage of crosscutting. The school party might be veridical; certainly the family would likely gather for Marmee’s birthday. But the scene could as well serve as the fictional epilogue in Jo’s book (as it does in the Alcott original).

The true epilogue of Jo’s story would then be the moment when she sees her book printed, action that’s crosscut with the celebration. Jo gets the first copy. In the last shot, pleasure, apprehension, and determination play across her features. And she’s framed in a window, an approximate reverse shot to the image that opened the film (see image at the top of this section).

From the start Gerwig has shrewdly foreshadowed the turn to fiction by presenting the film’s title, after Jo has made her first sale, not as an inscription on the screen but as the physical book itself. That book is signed by L. M. Alcott. The apparently identical volume that comes off the printing press at the end bears the name J. L. March. Gerwig has let Jo appropriate Alcott’s story.

By giving us a double-voiced ending, Gerwig does something quite bold. Little Women becomes something of a “what-if” movie, positing two paths for her heroine. Alcott’s Jo had given up a literary career, whereas Gerwig’s Jo finds one by writing her own life and adding an optional ending. We’re free to think that Jo and Friedrich married and the family became a harmonious whole, as in Alcott’s book. A happy ending, we might say, for those who want one. But this film about hugs ends with the heroine hugging not a husband but her novel.

Unmarried in life, Jo can marry in fiction, and Gerwig can have it both ways. Narrative lets you do things like that.

I haven’t been able to do justice to the intriguing choices made in other films of the season. I appreciate, for instance, the nonlinearity in Kasi Lemmons’ Harriet, where the interruptions of present-time action offer Harriet’s premonitions of future scenes. This sort of “prophetic” flashforward is rare; usually such passages are presented as omniscient narration, not assigned to characters. But the device does establish Harriet as a sensitive, almost angelic figure, and suggests that her quest to guide slaves to freedom is sustained not just by faith but by holiness.

Still, looking in a little depth at just two major films can make us aware of several choices available to filmmakers at this point in history. As Wölfflin said, “Not everything is possible at all times.” But film researchers can usefully trace the flexible menu of options that filmmakers work with, and film viewers come to master.

Gerwig has kindly made available a version of the screenplay [41], which I discovered only after I wrote this. (Thanks, Kristin.) The notations for the final sequences are pretty interesting. The most wide-ranging discussion I’ve seen of the ending, with plenty of links, is the conversation between Marissa Martinelli and Heather Schwedel [42]in Slate. Among several perceptive reviews, I’d single out the one in Time [43] by Stephanie Zacharek and Richard Brody’s review [44]in The New Yorker.

I can’t help but think how central crosscutting, that technique pioneered by early filmmakers, is to both of these films. Techniques endure because they open up a lot of expressive possibilities.

Kristin elaborates on arguments for four-part plot structure in Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique. Extended examples on this site are here [45] and here [46]. I discuss family sagas of the 1940s, along with flashbacks, protagonists, and other narrative techniques in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling [47]. On 1990s revival of these techniques, see The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies.

Marriage Story (2019). Is this why the film includes few standing two-shots of Nicole and Charlie?