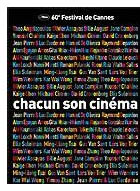

Can you spot all the auteurs in this picture?

Wednesday | June 6, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Some movies consist of several distinct episodes, each directed by a different filmmaker and all focused on a single theme. I’ve heard them called anthology films, omnibus films, and portmanteau films.

The earliest one I know is If I Had a Million (1932); later, Hollywood offered us Ziegfeld Follies (1946) and O. Henry’s Full House (1952). The Brits gave us the horror anthology Dead of Night (1945). Still, I think we associate the form chiefly with European cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. We got Love in the City (1953), Amori di mezzo secolo (1954), The Seven Deadly Sins (1962), RoGoPaG (1963), Les plus belles escroqueries du monde (1964), Paris vu par . . . (1965), Three Faces of Woman (1965), The World’s Oldest Trade (1967), and Amore e rabbia (1969).

Why the emergence of omnibus movies at this point in history? Some causes are surely financial. Most high-budget European films of the period had to be cross-national coproductions. Bringing in directors from several different countries could help guarantee funding under EU auspices and participating nations’ subsidy schemes. Just as important, the anthology format appeared when the festival scene was starting to become a vast clearing house for international film trade.

Although you can argue that many people seeing If I Had a Million would recognize the Lubitsch episode, Hollywood’s use of the form didn’t stress directorial differences. But as the Euro auteur was becoming a marketable commodity in the postwar era, a collection of short films could sell if they were signed by big-name filmmakers. “Paris As Seen by…” signals the importance of the different directorial approaches, and the very title of RoGoPaG invokes Rossellini, Godard, and Pasolini as brand-name labels. (Granted, the final G, Hugo Gregoretti, didn’t add much to the deal.)

For full enjoyment, the 1960s portmanteau film requires a degree of specialized film knowledge. At one level, we enjoy varied treatments of a theme, but at another we’re supposed to recognize each director’s personal vision, as we know it from other films. Even political-commentary portmanteau films like Far from Vietnam (1967), Lucía (1968), and Germany in Autumn (1978) gathered international attention because of the name recognition of the filmmakers who participated. The same branding operates in New York Stories (1989) and, more openly, in the documentary 12 registri per 12 città (“12 Directors for 12 Cities,” 1989).

The format has returned recently. We’ve had 11’09”01—Sept. 11 (2002), Eros (2004), Tickets (2005), and Paris, je t’aime (2006), the last virtually a rebooting of Paris vu par . . . . As we’d expect, such films continue to highlight the personal signatures of festival familiars. But we can spot some new twists too.

For one thing, the unifying idea may be formal as well as thematic. The episodes of 11’09”01 were all obliged to be the same length, eleven minutes, nine seconds, and one frame. Lumière et cie (1995) not only celebrated the centenary of film but obliged the directors to make their entries with a Lumière camera, to shoot without sync sound, to shoot no more than three takes, and to restrict the length to 52 seconds, the approximate running time of the earliest films. The Lumière homage also introduces the key themes of cinema and cinephilia, an angle that doesn’t seem prominent in the 1960s omnibus movies.

The most prominent portmanteau film so far this year fits snugly into current trends. As Anthony Kaufman writes, “Chacun son cinéma. . . showcases a range of filmmaking aesthetics, and for the most part, the program is a dazzling and memorable array of current auteur cinema.” As in other eras, we get a stylistic buffet; as in recent years, we find formal constraints and the theme of cinephilia. Commissioned for Cannes’ sixtieth anniversary by festival head Giles Jacob, the project restricts filmmakers to three minutes per episode and dictates the subject: “their state of mind of the moment as inspired by the motion picture theater.” The result was 33 short films about the joys and sorrows of film viewing and, to some degree, an extended commercial promoting the cultural value of the Cannes event.

The most prominent portmanteau film so far this year fits snugly into current trends. As Anthony Kaufman writes, “Chacun son cinéma. . . showcases a range of filmmaking aesthetics, and for the most part, the program is a dazzling and memorable array of current auteur cinema.” As in other eras, we get a stylistic buffet; as in recent years, we find formal constraints and the theme of cinephilia. Commissioned for Cannes’ sixtieth anniversary by festival head Giles Jacob, the project restricts filmmakers to three minutes per episode and dictates the subject: “their state of mind of the moment as inspired by the motion picture theater.” The result was 33 short films about the joys and sorrows of film viewing and, to some degree, an extended commercial promoting the cultural value of the Cannes event.

A half-dozen things strike me while watching the French DVD version (which has English subtitles but is unaccountably lacking the Coens’ entry). Most notable, I suppose, is the way that many of the shorts replay tendencies that are characteristic of art cinema generally (1).

1. Cinema invokes eroticism . . . We get a dreamy Wong Kar-wai scene of a man watching, or recalling, heavy petting in the theatre. Polanski’s episode plays amusingly on the similarity of orgasmic moans and painful groans. Gus van Sant’s First Kiss reinvents Sherlock Jr., while the Dardenne brothers give us a tight tale of hands in the dark. Olivier Assayas’ episode, a crisp piece of filmmaking, reveals its l’amour fou at the very end. Angelopoulos makes clever use of the Kuleshov effect to create a touching exchange between Jeanne Moreau and the lamented Mastroianni.

2. . . . and childhood, especially for the Chinese directors, who haven’t exactly risen to the occasion here. The international art film has long traded on the appeal of kids, but the treatment of them in these episodes is remarkably banal. Tsai Ming-liang, who already passed his benediction for classic cinema in Goodbye, Dragon Inn, gives us a dream of a family reunited at the pictures. Chen Kaige shows children watching—hold on now—a silent Chaplin film. Hou Hsiao-hsien provides a sepia-toned flashback to going to the movies in Taiwan, while Zhang Yimou takes us to movie night in a Mainland village. At least the Hou episode opens on a lengthy shot that nicely decenters areas of interest in a busy street scene.

3. The cinema is on the decline . . . . One way to interpret Kitano Takeshi’s cryptic sequence is that films, even his own Kids’ Return, are little more than an anachronism today. More explicitly, David Cronenberg’s single-take close-up, captured by a surveillance camera shows himself as the world’s last surviving Jew, on the threshold of suicide in a movie house.

4. . . . yet it holds us in a magical spell. Some directors celebrate the simple folk at the movies. Claude Lelouch’s parents watch Top Hat and fall in love. Raymond Depardon takes us to a rooftop cinema in Alexandria, and Wenders shows a Congolese village running Black Hawk Down on video (more kids, but this time to disturb us). Kaurismaki seems to be poking fun at this arthouse commonplace by showing foundry workers blankly watching a rather different image of workers at the end of the day. The cinema, Ruiz and González Iñárritu suggest, mesmerizes even blind people.

Walter Salles provides a charming, deflating musical dialogue (below) that might be called Far from Cannes, showing that this festival casts a quasi-religious spell felt across the world. In my favorite section, Kiarostami gives us shots of women responding to Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. The image/sound pairing hints at their own thwarted loves, while certain lines, such as “Where be these enemies?,” seem addressed to Westerners who try to dehumanize the people of Iran.

5. Film can be silly. Von Trier, decked out in a tux, silences a businessman through extreme means, and the rest of the audience hardly notices. Jane Campion, in an awkward episode, reveals a bug living in a theatre speaker. Probably the funniest contribution shows a mute Elia Suleiman preparing for a Q & A session after a screening. There are more gags in this three minutes than in all the other episodes put together.

5. Lest we forget . . . This couldn’t help but be a nostalgia exercise, encouraging filmmakers to muse on their lives in cinema. This theme recalls Cinema Paradiso, Scola’s Splendor, and all the other films soaked in the melancholy sweetness of movie memories. Moretti (top image above), gives us an anecdotal monologue, while Youssef Chahine unashamedly thanks Cannes for giving him an award ten years ago. The most formally ingenious entry here is Atom Egoyan’s tale of a couple sitting in different screenings while texting each other. Eventually one grabs an image from La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and passes it along, creating a parallel to what’s happening in the other film (Egoyan’s The Adjuster).

In particular, there’s nostalgia for the golden age of auteurs, the very period when the anthology film gained its purchase. Chacun son cinéma is dedicated to Fellini, and Konchalovsky’s episode centers on 8 ½. Bresson and Godard are the most frequently referenced directors. (More generally, in our new century Bresson seems to have become the prototype of the serious filmmaker.) Other icons of the 1960s, such as Mastroianni and Anna Karina, keep popping up.

6. Spot the auteur. Most episodes don’t reveal the director’s name until the end, so the cinephilia takes on a suspenseful dimension, forcing you to guess who filmed the bit you’re watching. You also have to identify movies within the movies on the basis of clips and soundtracks. It’s a great game for arthouse aficionados, but it also highlights festival cinema’s reliance on the cult of the director and the organic unity of his/her body of work.

Suppose that all these films omitted the director’s name and replaced the recognizable players with nobodies. Would any of these episodes have been accepted for Cannes’ short film programs? Probably not, but we shouldn’t be cynical about this. Clearly artworks can gain in interest by virtue of their place in history or an artist’s career. Renoir’s Sur un air de Charleston (1927), Bresson’s Les affaires publiques (1934), Dreyer’s They Caught the Ferry (1948), and Fassinder’s episode in Germany in Autumn are not masterpieces, but these shorts show fresh sides of great filmmakers, and our understanding of their accomplishment is enriched by having them.

So we’re right to recognize the director’s career as a meaningful whole. But we should also recognize that today such careers continue thanks to a distinct system of marketing. At the Cannes site, Rauol Ruiz says: “It’s a delight to be a preferred filmmaker and especially a favored filmmaker of Gilles Jacob.” The system depends on reciprocity. “Without the auteurs,” says Jacob, “there wouldn’t be a festival.” (2) In turn, auteurs are obligated to festival gatekeepers and tastemakers, the powerful critics, programmers, and impresarios. The filmmaker knows the drill. You showed my film last year, so yes, I’ll sit on a jury or offer a master class or show up on the red carpet this year.

We’re told by Anne Thompson that a more complete DVD edition, including the David Lynch entry, will be available before Christmas. That gesture makes the disc I bought the equivalent of the plain-vanilla DVD of a blockbuster that will be followed at the right moment by the Deluxe Edition. Who says the art cinema operates above pressures of business and the market?

(1) I discuss the idea of art cinema in a 1979 article, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” revised in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.

(2) Nancy Tartaglione-Vialatte, “‘Without the auteurs there wouldn’t be a festival,'” Screen International (May 18-31, 2007), p. 15. See also the accompanying article by Nick Roddick, “The bucks start here,” pp. 14-15. These are available online to subscribers.

PS: Speaking of Cannes and the art cinema, I wrote an essay about camerawork in contemporary Danish film for the festival issue of the Danish Film Institute magazine. It’s now online here (pp 22-26). And speaking of Danish filmmakers. . . .

Atom Egoyan, Artaud Double Bill.