Kristin here:

Students and faculty in the film-studies division of the Department of Communication Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison are known for aesthetic analysis of films and historical study of the film industry. One aspect of the latter has been the study of franchises. Long ago Henry Jenkins coined the term acafan [2], defined as someone who is a fan of what he or she studies but also produces academically solid publications on it. His Textual Poachers (1992, second edition 2012) became a classic in the study of fandoms. His Convergence Culture (2008) examined the relationship between fandoms and film, television, and other media franchises.

Henry studied under David here at the university. I think it’s safe to say that David was also an acafan when he wrote about Asian action cinema in Planet Hong Kong (2000, second edition 2011, available as a PDF here [3]). I, too, admitted to being an acafan when I wrote my study of Peter Jackson’s (or should I say New Line’s) Lord of the Rings films in The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (2007).

In 2016 I took a look at the continuation of the [4]LOTR [4]franchise [4], which was still going strong then and is still going strong now. No doubt next year, when we reach the twenty-fifth anniversary of the release of The Fellowship in the Ring, there will be considerable exploitation of re-releases and yet more licensed products.

More recently Colin Burnett, another of David’s students, known for his study of Robert Bresson [5], has turned his enthusiasm for the James Bond franchise into a research project. I am happy to see him discovering shifts in control of the film and merchandising rights that somewhat parallel those in the LOTR franchise, most notably with Amazon’s ambitious prequel series, The Rings of Power. Thanks to Colin for contributing an entry dissecting and clarifying the recent Variety article announcing Amazon MGM’s acquisition of the Bond film franchise.

Amazon Doesn’t Own James Bond–Yet

In a development that has shocked the entertainment industry, Amazon MGM announced on February 20, 2025 [6] that it had taken over “creative control” of the James Bond film franchise. What exactly does this mean, and why is it so shocking?

Reporting on the news has tended to overlook some crucial details about the structure of the Bond franchise, a factor which in turn has colored the speculations of commentators and fans. Variety’s February 20 headline [7], for instance, alleges that “Amazon MGM gains creative control of 007 franchise.” This simply isn’t the case.

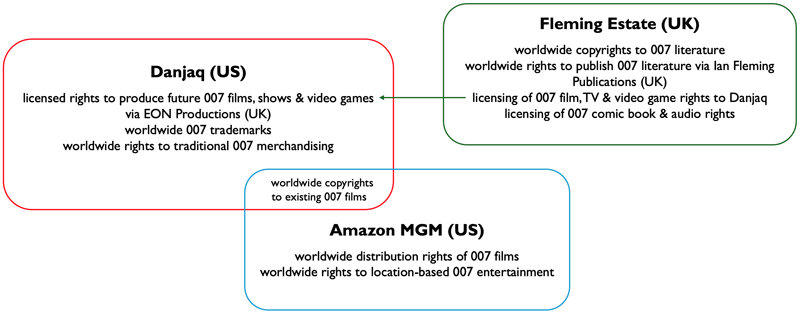

The Bond franchise is configured as a shared rights and licensing network (above). For decades, even prior to Amazon’s acquisition of the studio in 2022 [9], MGM has owned the worldwide distribution rights of the Bond films, as well as shared copyrights for the existing Bond film titles. The new pact, which some price at $1 billion [10] (unconfirmed), gives Amazon MGM the power to manage the artistic direction of the film series for the first time, and thus presumably a controlling stake in a company called Danjaq.

How did we get here?

Danjaq/EON Productions’s shifting media franchising strategy

Until now, production of the film series has been in the able hands of the Broccoli family. In 1961, producers Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli and Harry Saltzman optioned Ian Fleming’s novels and formed Danjaq [11], a rights holding firm initially based in Switzerland (now in the US). To produce their Bond film series, Broccoli and Saltzman acquired the small British production company EON Productions, allowing them to benefit from British tax breaks and subsidies. They also formed a partnership with Hollywood studio United Artists (UA) to finance and distribute their projects. Over the years, there have been changes here and there—MGM acquired UA in 1981, and Broccoli’s stepson Michael G. Wilson and daughter Barbara Broccoli took the reins of EON/Danjaq in 1995—but the EON/MGM arrangement has remained relatively stable.

The decades-long partnership between EON and MGM has always favored the Broccolis. Through EON, they shaped the creative direction for the series, and through Danjaq, the Broccolis managed the copyrights for the cinematic Bond and the global Bond trademarks. But when the multinational technology company Amazon purchased MGM in March 2022, it acquired considerable leverage in the Bond franchise. Almost immediately, tensions began to surface between EON and MGM. The longtime partners couldn’t agree on the next steps for the series.

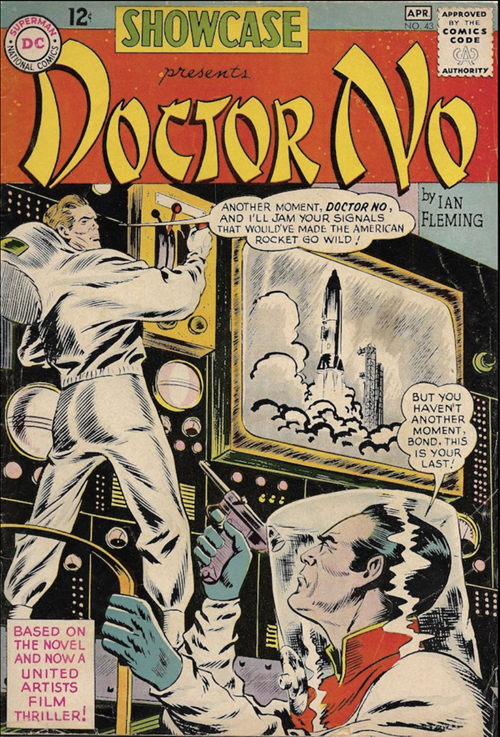

Reports indicate [12] that Amazon MGM was intrigued by the possibility of a James Bond Universe akin to Disney’s Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars Universe. The concept is not a foreign one to Bond producers. Between 1961 and 2002, EON worked with partners in numerous popular media to spread the Bond story throughout the market. They licensed publishers DC, Dell, Marvel, and Topps comics [13] to adapt their films into comic books, such as the 1962 DC Showcase 32-page comic book adaptation of the film Dr. No.

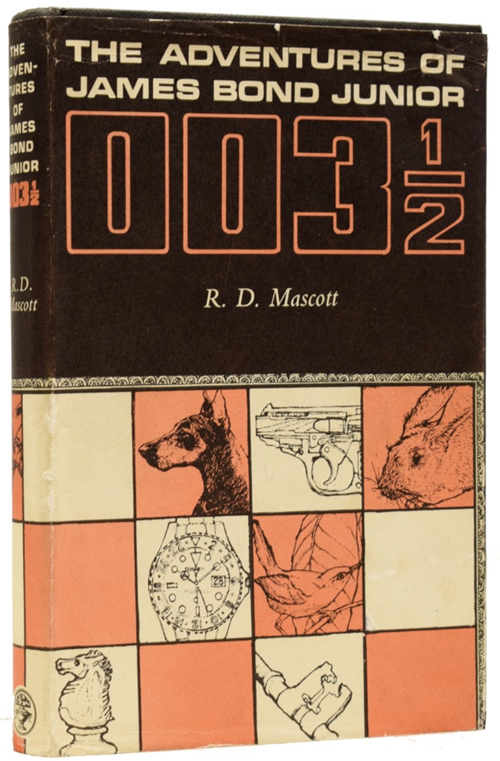

In the 1960s, they showed interest in a children’s TV series based on the 1967 novel The Adventures of James Bond Junior 003 ½ [15] , published by Ian Fleming publisher Jonathan Cape. The concept came to fruition with the syndicated show James Bond Jr. (1991-1992) [16].

In the early 2000s, they started development on a spinoff film titled “Jinx,” [18] based on the Halle Barry character from the 2002 film Die Another Day. And for decades, EON has worked with video game designers to create interactive adventures, the most famous being GoldenEye 007 (1997) for the Nintendo 64 system [19]. In fact, there’s a new EON-licensed game [20] in the works.

In recent years, EON has devoted most of its resources to the films, whose productions became more ambitious [21]. Perhaps sensing Bond’s uniqueness in the market, where franchises saturate consumers with content—Marvel and Alien movies and streaming series, Star Trek shows, Star Wars games, Avatar comics, etc.—EON opted for a more restrained approach that focused on films, creating the impression that they were “specials” and avoiding product overexposure. There have been exceptions. When the Daniel Craig era came to an end with 2021’s No Time to Die, EON signed with Amazon Prime—prior to the Amazon’s acquisition of MGM—to partner on the reality show 007’s Road to a Million. The series required little creative investment on Wilson’s and Broccoli’s part, and Bond doesn’t appear in the show, protecting EON’s most valuable commodity.

Amazon MGM’s notion of a cross-media Bond Universe simply didn’t appeal to EON, and the development of a series to follow the Craig films stalled. Exacerbating the situation, reports are that EON was flummoxed [22] about how to relaunch the films after the creative and financial triumphs of the Craig era.

Why did EON step away?

Commentators have alleged that these creative impasses placed pressure on Wilson and Broccoli to sell their creative stake in the film series. But other developments suggest that the picture is more complicated.

Media franchises like Bond, the Lord of the Rings, Oz, and Marvel are all about rights. In recent weeks, peculiar news has surfaced in The Guardian (UK) [23] about an Austrian-born developer named Josef Kleindienst, owner of a luxury property empire in Dubai, filing a number of “cancellation actions based on non-use” in UK and European courts. His ambition is to claim ownership of a broad swathe of Bond trademarks. These trademarks—for such items as computer programs, electronic comic books, electronic publishing and design—have not been used for a period of five years. Kleindienst is alleging that Danjaq’s trademarks for “James Bond Special Agent 007,” “James Bond 007,” “James Bond,” “James Bond: World of Espionage,” and the expression “Bond, James Bond” are subject to challenge.

These legal challenges, assuming they have standing, would have placed EON/Danjaq in the difficult position of having to battle a well-resourced foe in court or to quickly roll out product to renew their trademarks. A loss of even some of these trademarks could be devastating for the franchise. Acquiring the trademarks would not be easy [24], but were Kleindienst to succeed, he could at least in theory challenge or seek compensation from the production and release of any product seeking to use the James Bond name. Perhaps Wilson and Broccoli elected to sell their controlling stakes in Bond to avoid a protracted legal battle. Perhaps, too, the multi-billion-dollar firm Amazon MGM stepped in, and agreed as part of the deal to fight these impending trademark challenges to keep all Bond rights under the EON-MGM tent.

If such speculation has merit, then Wilson and Broccoli ceded creative control because it was their only major bargaining chip with Amazon MGM. The deal would ensure their continued roles as stewards of their portion of the Bond rights. After all, even EON/Danjaq doesn’t own all of the Bond intellectual property. The literary, audio, and comics rights are retained by the Ian Fleming Estate and managed by the firm of Ian Fleming Publications (IFP). In a statement issued on its website [25], IFP addressed the Amazon MGM deal, acknowledging Wilson and Broccoli “for their remarkable stewardship and vision. Their imagining of James Bond on screen has created one of the world’s great film franchises and has led the incredible success of the British film industry.”

What lies ahead for 007?

Here too there’s much speculation. Most fans of the film series seem skeptical about the new Amazon MGM era, concerned that Bond will become just another media franchise. An Ellis Rosen New Yorker cartoon [26] captures the general mood, showing Jeff Bezos—in the guise of Bond villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld—standing over a bound James Bond who lays prone under the Amazon Swoosh symbol in a position reminiscent of the famous laser-torture sequence from 1964’s Goldfinger. In the original, Sean Connery’s Bond says to rival Auric Goldfinger, “You expect me talk?” Goldfinger’s answer is iconic—“No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die!” In the New Yorker version, Bezos responds, “No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to star in a series of increasingly bland spinoffs and TV shows that have significant viewership decline after the first episode.”

One thing’s for certain: Bond has entered the “content” era. The film franchise will no longer focus on films alone. Given its extraordinary resources, Amazon MGM may even make a bid for all Bond rights, including a buyout of IFP, bringing the Bond property under one rights-holding company for the first time since the 1950s.

In the meantime, will Amazon MGM respect the Bond film property? Will it treat the replacement of Craig with the same care EON addressed the “new Bond” question in the past? Will it pursue EON’s commitment since the onset of the Craig era to “quality” blockbuster production, with an emphasis on location shooting, practical effects, and adherence to the spirit, if not the letter, of the Fleming version of the character? I have reasons to doubt some of this.

Among other concerns, the copyrights to Ian Fleming’s original Bond stories expire in the UK in 2034, a date that marks 70th anniversary of the author’s death (Fleming’s works are already in the public domain in Canada. [27])

Amazon MGM has just under a decade to exploit the Bond film rights before competitors are legally able to launch their own adaptations of Fleming’s 007. We can expect more studio-bound, computer-generated (CG) productions, which is more efficient than the location-based approach of EON and today drives most major franchise filmmaking. We can also expect streaming series: a Felix Leiter series, a Moneypenny series, or perhaps a Lashana Lynch 007 series or a Jinx series. Perhaps we can expect Amazon MGM to option a number of the “Bond Continuation” novels released by IFP [29] since Ian Fleming’s death in 1964. Most assuredly, we can expect a “mothership” theatrical series with a new Bond, and even a revival of the James Bond Jr. animated series, for which some fans are nostalgic. Amazon MGM will do many of the things EON/Danjaq did or had hoped to do in the past but didn’t have the resources or bandwidth to do in recent decades.

We can expect, in short, what we’ve come to expect, over and over again. A new Bond era.

For more on EON Productions and its reliance on British film subsidies, see pages 41-42 and 55-56 of James Chapman’s Dr. No: The First James Bond Film (New York: Wallflower Press, 2022). See also Charles Drazin, A Bond for Bond: Film Finances and Dr. No (London: Film Finances, Ltd., 2011).

For a detailed account of the original deal between EON and UA/MGM, see chapter eight of Tino Balio’s United Artists, The Company that Changed the Film Industry, Volume 2, 1951-1978 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987).

Colin Burnett is Program Director and Associate Professor in the Film & Media Studies Program at Washington University in St. Louis. He is the author of two books, including one on the major French director Robert Bresson [30]. He has written an article on storytelling in the James Bond film series for the Journal of Narrative Theory [31] and is completing a new book entitled Serial Bonds: The Shape of 007 Stories.