Archive for December 2006

An appetite for artifice

Offscreen (Christoffer Boe)

DB here (no, not above):

Catching up with several of the fall’s films, I was struck by how often they played quite self-consciously with the overall shape of their plots. Here are some examples.

Network narratives. This is the label I applied in The Way Hollywood Tells It to those films highlighting several protagonists inhabiting distinct, but intermingling, story lines. In Poetics of Cinema, I have an essay examining the conventions of this format. Several films I saw this fall continued this tradition.

*Bobby used the familiar device of gathering everyone in a single spot–a hotel–within a short time frame and interweaving personal stories with a fateful climax. I thought the film was fairly clumsy, but I was still moved. In 1964 I filmed RFK when he stumped our town for the presidential nomination, and in college, though leaning toward Gene McCarthy I thought Bobby was the only candidate who could beat the Republicans. “Dump the Hump!” (Hubert Humphrey) was the rallying cry.) His assassination, during the same year Martin Luther King was killed, was very traumatic to young idealists. Estevez’s film becomes most powerful, I think, by simply replaying footage and speeches, reminding us that there was once a rich politician who talked incessantly about helping the poor. Just as Stone’s JFK positioned Jack as the man who could have averted the Vietnam War, Bobby makes RFK the anti-Bush.

*Fast Food Nation was for me a more satisfying use of the network narrative format. Here the time scheme is more diffuse because Linklater is tracing a large-scale process, the burger from the hoof to the Happy Meal. By starting with the middle-management character (Greg Kinnear) and then easing us into the harsh working life facing Mexican illegals, the film builds sympathy for the immigrants. Gradually, the illegals’ stories take over, and the social conscience of one of the burger chain’s teenage workers is ignited.

The plotting makes some thoughtful moves. A more literal approach would have shown us the meat-processing plant’s killing floor early, as part of the step-by-step process. But here the shocking material isn’t presented until the very climax of the film, as the fate to which the immigrant working woman must submit. Likewise, the film drops the Kinnear character about halfway through, a ploy that conceals from us how he’ll act on his new knowledge. Will he blow the whistle on the plant, and endanger his job? A European film might have left his whole line of action open, but Linklater adheres to the tendency of American films to resolve a plotline one way or another. He does it, however, in an epilogue which leaves us with a sharpened sense of the acute problems of the system.

*The Uchoten Hotel (aka Suite Dreams, Japan, 2006). In the vein of Tampopo and Shall We Dance?, Mitani Koki offers gentle humor mixed with satiric social observation. Confusion reigns at the Avanti Hotel on New Year’s Eve, as a philandering professor, a corrupt Senator, low-end showbiz types, and the hotel staff become embroiled in one another’s lives. Lively long takes display subtle staging, and there’s a ventriloquist’s duck. A tribute to Grand Hotel, Billy Wilder, and Jacques Tati, this good-hearted survey of human aspirations was the most uncynical movie I saw all year.

Many critics seem to feel that the network format is tired out. At indieWire, Nick Schager calls for “a moratorium on second-rate Nashville-style ensemble pieces that seem increasingly to be the province of every Tom, Dick, and Emilio.” The key words are “second-rate”: Like any storytelling pattern, the network option can be used well or badly. Linklater and Mitani use it with flair.

The point I’d stress is that although the network model can claim to be a realistic device (in our world, our projects commingle), it’s almost always presented through a series of conventions–traffic accidents, people brushing past each other, narration that holds back information about the characters’ relationships, and so on. We recognize these as part of the artifice in this tradition of storytelling.

Broken Timelines. During his DVD commentary for Basic, John McTiernan uses this phrase to explain the film’s flashbacks and replays. In the terms we use in Film Art, the linear story action is scrambled or rearranged in the plot that that the film presents to us.

Screenwriters used to urge novices to avoid breaking up the timeline, but in the 1940s through the mid-1950s, films began to play around with story order. Citizen Kane (1941) probably encouraged the flashback form, as did film noir’s emphasis on mystery and crime detection. Siodmak’s fine The Killers offers a prototype. (I discuss its plot maneuvers in Narration in the Fiction Film.)

We don’t lack for flashbacks in contemporary films, but things are getting complicated. Today a film may open with a quite mystifying sequence, before backtracking to acquaint us with the situation. In itself, this isn’t very unusual, since flashback-based films have often opened at a point of crisis and then taken us back to the beginning of the action. The Big Clock and Written on the Wind are instances. The new wrinkle is to actually replay the opening situation or just the images from it in a new context.

*The Fountain by Darren Aronofsky offers one example. Using three time layers, it can keep replaying the opening portions in ways that recontextualize the material we saw at first. In its out-of-this-world realm, as well as its suggestion that the story is in some sense being written as we see it, it reminded me of Slaughterhouse-Five (1972)–another indication that these innovations aren’t brand new.

*Another instance: The opening image of Christoffer Boe’s Offscreen (2006), with a bloody Nicolas Bro in close-up advancing to the camera, gets explained only at the grisly climax.

*The recontextualizing replay isn’t an avant-garde device. Tony Scott’s well-done thriller Déjà Vu uses it in the context of a time-travel plot. It replays the opening sequence in a way that suggests both a branching or alternative future and a deeper understanding of what we saw initially. A similar pattern is found in Flags of Our Fathers, in which we reinterpret the opening differently now that we know the characters more fully. I suppose that Pulp Fiction‘s opening became a powerful influence on this formal choice.

When an action is replayed, it can be shown from different characters’ perspectives. Again, this was explored a lot in the 1940s, as in Mildred Pierce (a replay of the opening) and Crossfire (a replay of the crucial incident). The device is on display in The Killing and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance as well. Kurosawa’s Rashomon made the technique more ambiguous, by not confirming which version of events is accurate. The same idea guides the money exchange in Tarantino’s Jackie Brown, which we discuss in the new edition of Film Art.

*The broken timeline of Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada uses multiple points of attachment mildly, in the murder scene. The replays are more significant and fragmentary in The Prestige. More films in this vein are in preparation, including Vantage Point, which shows an assassination attempt on a US president as seen from five characters’ points of view, “unfolding in 15-minute increments.”

Companion films. Back in the 1960s, Fox announced that it wanted to make Tora! Tora! Tora! with two directors, one Japanese and one American. My friends and I indulged in a game: Whom should they pick? (I favored Ozu and Samuel Fuller.) As you probably know, Kurosawa’s collaboration came to naught (though he did shoot some footage, discussed by Richard Fleischer in his book and his DVD commentary on the film). Fukasaku Kinji and evidently some other directors contributed to the Japan-based footage.

Now, instead of one film with two directors, Clint Eastwood gave us two complementary films from a single hand. I haven’t yet seen Letters from Iwo Jima, but the very idea of showing the same battle from opposite sides in two movies acknowledges a level of artifice.

The French got here first, I think. Marguerite Duras made a companion film to her mesmerizing India Song (on right) called Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert. Son nom had exactly the same soundtrack as India Song but a wholly different image track–only landscapes around the site of action, empty (as I recall) of all human presence. A comparable instance is the alternate-worlds pairing by Alain Resnais, Smoking/ No Smoking, adapted from a cylce of Alan Ayckbourn plays.

The French got here first, I think. Marguerite Duras made a companion film to her mesmerizing India Song (on right) called Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert. Son nom had exactly the same soundtrack as India Song but a wholly different image track–only landscapes around the site of action, empty (as I recall) of all human presence. A comparable instance is the alternate-worlds pairing by Alain Resnais, Smoking/ No Smoking, adapted from a cylce of Alan Ayckbourn plays.

The companion-film concept seems to be expanding. Red Road, directed by Andrea Arnold, is launching a series of films to based in Scotland and all featuring the same group of characters, but filmed by different directors. The characters are conceived by filmmakers Lone Scherfig (Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself) and Anders Thomas Jensen (Brothers). In a way, a sort of episodic-television idea applied to feature films.

What’s behind this? Why are today’s movies using such self-conscious artifice in their plotting? Is form the new content, the way gray is the new black?

Complex storytelling can be found in a lot of other media today. It’s common to point to Hill Street Blues and later TV shows as reinforcing tendencies toward network narratives in film. Jason Mittell discusses the tendency in Velvet Light Trap no. 58. His article “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television” (available here), makes the case that shows like 24, Arrested Development, Buffy, Malcolm in the Middle, and so on have offered viewers ways “to be actively engaged in the story and successfully surprised through the storytelling’s manipulations”–a good way to describe some of the strategies I’ve been sketching.

In graphic novels and comic art we’re seeing the same tendencies. Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware manipulate time and space in virtuoso ways, as does the highly formalized movement known as OuBaPo. You can check out an American version of OuBaPo in Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story.

In graphic novels and comic art we’re seeing the same tendencies. Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware manipulate time and space in virtuoso ways, as does the highly formalized movement known as OuBaPo. You can check out an American version of OuBaPo in Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story.

In Everything Bad Is Good for You, Steven Johnson argues that people are just getting smarter, and so popular culture is pitched at a more sophisticated level. But quite complex artifice can be found in mass media of earlier eras. As I mention in The Way, we can find backward-told stories in popular fiction long before Memento, and Grand Hotel is an early prototype of the network narrative. Our ancestors weren’t necessarily dumber than we are, and popular art has long harbored experimental impulses.

I’d hypothesize some other causes. Regardless of IQ, more members of the audience have been to college today than in early eras. More of the creators have studied modern art and literature and are ready to borrow experimental devices they’ve encountered in other media. This process has a familiar ring. American filmmaking has often renewed itself by absorbing all manner of experiment, from German Expressionism (for 1930s horror films) to serial music (for 1950s psychological dramas). Usually, I feel compelled to add, the experimental devices are absorbed into existing forms, like classical script structure, genres, or stylistic principles.

I suspect as well that the new genre hierarchy that emerged in the last couple of decades cranked up the artifice level. The rise of science fiction, mystery, fantasy, horror, and comic-book movies probably encouraged clever juggling with story order, point of view, and states of knowledge. So did the rise of indie cinema, which needs narrative innovation to set itself apart from the mainstream. Again, Pulp Fiction fuses the two strands: an indie neo-noir that attracted attention through its bold manipulation of story/ plot relations.

At the same time, filmmakers in other countries have been eager to push the boundaries. Many of the broken-timeline devices have their sources in art cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. Younger European directors like Boe and Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run) have revived this adventurous attitude toward storytelling, putting them somewhat in sync with American directors. Asian experimentalists like Wong Kar-wai and Hou Hsiao-hsien continue to exercise a comparable influence.

We need to think more about where this impulse toward innovation comes from and how it shows itself, but it seems likely that the flourishing trade in self-conscious storytelling will be with us for some time yet. Hollywood cinema has long been self-consciously, almost fussily formal, and it has a vast appetite for artifice.

Another little DA VINCI CODE mystery

Kristin here—

First, a little background. In the new edition of Film Art, we have added a new feature. At the end of each chapter we recommend DVD supplements that tie in with the respective subject matter. The task of watching lots of supplements—around 60 films’ worth—devolved upon me. That wasn’t always as fun as it might sound. There were some informative sets of extras, but all too many were mutually congratulatory fests, with directors praising actors, actors praising directors, actors praising other actors, and so on. “X was just perfect for that role. I can’t imagine anyone else playing the part.” You know the kind.

Film Art’s new edition is finished, but I keep looking for supplements we can recommend here or in the ninth edition. One promising-sounding DVD set was the recent “Special Edition” of The Da Vinci Code, with 90 minutes worth of extras.

I know The Da Vinci Code has a so-so reputation based on the reviewers’ responses. I went to it during its first run and was pleasantly surprised. It’s no masterpiece, but the idea that it is dull or slow seems very odd. It was entertaining and reasonably well-made, and I enjoyed it. It’s certainly miles above the overly long Dan Brown novel, which has a tendency to have information revealed in the dialogue and then redundantly summarized in the third-person narration. It also has those thudding cliff-hanger sentences at the end of just about every one of its choppy little chapters. The movie positively races along in comparison. And the washed-out historical flashbacks during the Grail explanations have a loony, experimental feel to them that appeals to me. It’s startling to see such epic scenes tossed in briefly in the midst of a modern thriller. I can see, though, where others might dismiss them as silly.

I don’t know how it happens, but sometimes a film comes along that all the critics simultaneously decide to trash, whether it deserves it or not. Some sort of telepathic thing, maybe, or perhaps in this case they all consulted each other during the famous long press junket on a special chartered train traveling from London to Cannes this past spring. (Ian McKellen has posted an amusing account of answering the same questions over and over during this journey.) The Da Vinci Code was the opening-night film at Cannes, and that’s where the lukewarm critical response began. The reviews were completely ignored by moviegoers, who made The Da Vinci Code the second highest grossing film of 2006 internationally.

Anyway, having enjoyed the film and knowing that its DVD was laden with supplements, I set out to purchase it. Investigation on the internet turned up the surprising news that there was an “extended version” available. That was news to me, and no wonder. When I searched further, I discovered that this longer cut was not available in the U.S. While the familiar 149-minute theatrical version can be had here—complete with a replica cryptex if you buy the deluxe version—the unknown 168-minute version cannot. Not only that, but though I Googled as hard as I could, I could find no explanation as to why there would be an extended version at all and why we Yanks have no access to it.

There’s a Region 2 French edition, as advertised on Amazon’s French site. The Germans seem to have the best selection, with the extended version available on a simple two-disc set, a deluxe edition that throws in a cryptex, and a boxed set of the two DVDs with six CDs containing the audiobook. The long version is also available on Region 4 DVDs in New Zealand and Australia. I have not been able to locate any Region 1 (U.S. standard) DVDs of this version. By the way, all the DVDs, regular, extended, fullscreen, and widescreen seem to have an identical set of supplements.

Perhaps an extended Da Vinci Code is not at the top of everyone’s Christmas list, but the lack of availability or even knowledge of this version in the States is puzzling. Was there something in this longer version that would bore, offend, or otherwise put off American viewers? Which version would one write about in doing some sort of analytical essay on The Da Vinci Code? Aided by eBay and a multi-standard DVD player, I set out to investigate.

The copy I bought, an Australian one, doesn’t have a list of where the extra footage comes. I didn’t sit down with two DVD players and two monitors side-by-side, so I can’t pinpoint every single difference. I had seen the film in a theater in June, and upon watching the extended version, I was able to spot ten additions, ranging from a couple of shots at the beginning of a scene to five new sequences. I don’t think these add up to an extra 26 minutes, so there are presumably some I missed. Those who are interested can have the pleasure of ferreting out all the details of the extra footage for themselves. (It does make one appreciate the Lord of the Rings extended-edition menus, where changes are marked with asterisks.)

One can understand why a longish film would be trimmed by 25 minutes. It’s enough to reduce by one the number of times it could be screened per day, which is clearly a significant obstacle.  Still, the extra scenes and bits do make a difference, though it’s often minor. In the scene at Teabing’s (Ian McKellen) country house where the group moves from the kitchen to the study to look at the Last Supper slides, the establishing shot of the new setting has an oil painting of a woman framed prominently in the foreground. It presumably was meant to hint at a backstory for Teabing, some great lost love whose absence may have contributed to the man’s obsession with the Grail. The painting is clearly visible in one shot of the shortened version, but since it comes during the invasion of the house by Silas (Paul Bettany), the viewer is not likely to notice it.

Still, the extra scenes and bits do make a difference, though it’s often minor. In the scene at Teabing’s (Ian McKellen) country house where the group moves from the kitchen to the study to look at the Last Supper slides, the establishing shot of the new setting has an oil painting of a woman framed prominently in the foreground. It presumably was meant to hint at a backstory for Teabing, some great lost love whose absence may have contributed to the man’s obsession with the Grail. The painting is clearly visible in one shot of the shortened version, but since it comes during the invasion of the house by Silas (Paul Bettany), the viewer is not likely to notice it.

Later, in the conversation between Fache (Jean Reno) and his assistant at the airport, Fache asks whom he has betrayed in using his ruthless means to pursue Langdon. In the release print, the assistant simply tells Fache that Teabing’s plane has changed course and is going to London. In the longer version, he goes on to say that he will bribe the airport official that Fache has beaten up. Thus rather than simply doing his duty and giving Fache information, the assistant firmly allies himself with his boss in his illegal doings.

Another brief extra moment comes in the second scene of Silas flagellating himself. The theatrical version cuts away from the action rather abruptly. In the extended version we see a quick series of flashbacks to previous murders that he has committed, presumably all at the behest of Bishop Aringarosa. Not really necessary to the plot, but it does make it clear that Silas realizes that his actions are reprehensible.

These are mere nuances, but the longer added scenes contribute more significant material. Two brief conversations show Aringarosa alone with the head of the Opus Dei council, basically establishing their collusion outside the council meeting itself.

Another new scene takes place aboard Teabing’s plane. It is a conversation in shot/reverse shot, with Sophie (Audrey Tautou) despairing and telling Langdon (Tom Hanks) to go to the U.S. embassy once they reach London, ending his efforts to help her. She suggests that she will simply throw the cryptex away. His insistence that he will stick with her creates one of the most emotionally charged moments between the two. Many critics complained that the Sophie-Langdon relationship lacks chemistry, but this scene’s restoration helps by showing a warm exchange between them. (Not that a lack of chemistry is a problem, given that the two are not supposed to be forming a romantic couple, just a friendship born of necessity.)

The second added sequence comes after the scene in the Temple Church, with a cut back to Teabing’s château. Fache’s assistant inspects an elaborate surveillance post in the barn, including recordings marked with the names of the four men killed by Silas. This event makes it quite clear why in the climactic scene at Westminster Abbey Fache arrests Teabing rather than Langdon and Sophie. In the shorter version, his change of quarry is rather fuzzily motivated by his realization that Aringarosa has duped him. (Maybe I missed some other plot point, but the surveillance-post scene certainly makes things clearer.)

inspects an elaborate surveillance post in the barn, including recordings marked with the names of the four men killed by Silas. This event makes it quite clear why in the climactic scene at Westminster Abbey Fache arrests Teabing rather than Langdon and Sophie. In the shorter version, his change of quarry is rather fuzzily motivated by his realization that Aringarosa has duped him. (Maybe I missed some other plot point, but the surveillance-post scene certainly makes things clearer.)

Finally, a new scene follows Fache’s arrest of Teabing. The detective meets with Langdon and Sophie in an office and expresses his regret over having wrongly pursued them: “I should have been smarter.” Although not necessary to the plot, this scene does give more prominence to Fache’s character, making him a more sympathetic figure.

It presumably made sense to cut these sections to allow for more screenings in theaters, but the question remains, why was the extended version not released in the U.S.? Along with all the commentaries and supplements that the studio added on, surely the words “extended edition” would have added some appeal to the DVD set. After all, the longer version was made and released elsewhere, so presumably the added expense wasn’t an issue.

The only reason I can think of is that the added scenes weren’t considered obvious or flashy enough for American audiences. Extended editions on the Lord of the Rings model tend to be done for fantasy and sci-fi films or other genre pictures that might be assumed to have a fan audience eager for any little extras they can get. Maybe that’s not assumed to be the case for other types of films. But then why bother to do such a version for the rest of the world? I’m baffled.

For those living in Region 1 territory who like The Da Vinci Code and who have a multi-standard DVD player, you might want to take the extra trouble to track down the extended version. There always seem to be a few on eBay (though watch out for the bootleg copies someone in Asia is selling there!), and they can be had through the big internet sellers in Europe and Australia.

Mad City’s movie mania

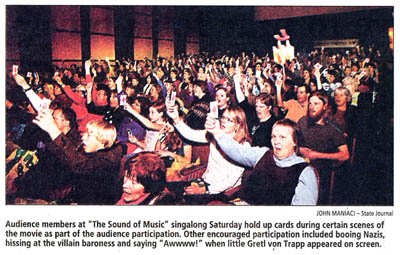

The Hilldale Theatre of Madison, Wisconsin opened its doors in spring of 1966 roadshowing The Sound of Music, and last weekend the theatre closed. To celebrate its passing, the management held a Sound of Music Sing Along, complete with subtitles to help with the lyrics. (No, not “How do you hold a moonbeam in your hand?” but the really tough ones.)

People came dressed as Maria, nuns, and the frog that was slipped into Maria’s pocket. There were cues for audience interaction, including saying “Awwww!” when Gretl appears on screen. This brought back memories of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which ran at midnight shows at the now departed Majestic Theatre from 1976 through the mid-1990s. For a report on that, and the connubial bliss it brought, have a look here.

Kristin and I came to Madison in fall of 1973, prime time. The campus boasted 22 film societies: Wisconsin Film Society, Fertile Valley, Green Lantern, Hal-9000, and all the rest. Members of the Union Film Committee, overseeing the only campus 35mm venue, were passionately debating whether to show Godard, or Jancso, or a John Ford retrospective. I convinced them to show The Young Girls of Rochefort, which hurt my reputation,and Play Time, which I think helped it.

The Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research had just acquired several thousand Warners and RKO films. The Majestic Theatre ran double and triple bills (kung-fu, Leone’s Dollars trilogy). The Velvet Light Trap magazine was going strong, run wholly by students and semi-students.

In those days, before home video, it was glorious to be in Mad City. We had 6-10 movies to see every night, apart from course screenings. We didn’t even own a TV. Who needed one?

Not to mention the cast of characters, all colorful. In the late 1960s-early 1970s the film community included:

Not to mention the cast of characters, all colorful. In the late 1960s-early 1970s the film community included:

The late Mark Bergman, premiere projectionist, fan of Phil Karlson, and gentle soul.

Joe McBride, critic (Variety), screenwriter (Rock and Roll High School), actor (The Other Side of the Wind), and excellent biographer (Spielberg, Capra, Ford, now Welles; What Ever Happened to OW? is very engaging).

Mike Wilmington, one of America’s top film critics, a mainstay of the Chicago Tribune.

Tim Onosko, author of Wasn’t the Future Wonderful?, industry consultant, and documentary filmmaker.

Gerry Peary, enterprising critic, screenwriter, and film professor.

Danny Peary, most famous for his series of Cult Movies books.

John Davis, co-founder of the Light Trap and creator of Capital City Comics.

Susan Dalton, another co-founder of the Light Trap and archivist at the American Film Institute.

Pat McGilligan, prolific critic, interviewer, and biographer.

Tom Flinn, the other co-founder of the Light Trap, pop-culture encyclopedist, and expert on Germans in Hollywood.

Bill Banning, founder of Roxie Releasing and operator of San Francisco’s Roxie Cinema.

Reid Rosefelt, publicist, producer’s rep, and filmmaker.

Many of these worthies ran film societies, so their ideas and passions showed through the films they screened. For more on the Madison Movie Mafia, go here.

Also present and active in late 1960s-early 1970s:

Filmmakers Erroll Morris, Stewart Gordon, Jim Benning, Bette Gordon, Michelle Citron, Karyn Kay.

Scholars-in-training James Naremore, Doug Gomery, Maureen Turim, Fina Bathrick, Marilyn Campbell, Diane Waldman, Ed Branigan, Vance Kepley, Peter Lehman, Brian Rose, Peter Brunette, Frank Scheide, and many more.

Great days, and nights…Mike Wilmington has written a fond appreciation of the whole scene here.

But this isn’t just an exercise in baby-boomer nostalgia. The Madison Cinema Juggernaut rolls on. The Light Trap just published its 58th issue. The Onion, founded by Madison students, continues to be America’s finest news source. Dan Fuller makes silent films with his students, using cameras from the 1920s, and the results have played at Pordenone. And not least, the Cinematheque, founded by faculty and students in the Communication Arts Department, carries on the spirit of the old film societies.

In sync with the closing of Hilldale, our Cinematheque ended the semester last weekend. (Crowd starting to gather above.) An outstanding schedule (S. Ray, Tarr, Godard, Sjostrom.) wound up with Lau Kar-leung’s Dirty Ho, the last of our string of Shaw Brothers classics. It was, of course, a delight, full of flamboyant, good-humored, and downright weird kung-fu.

A lot of it was close-quarter work, as warriors examining pottery or sampling wine disguise their deadly thrusts as elaborate courtesy. Lau is arguably Hong Kong’s top martial arts choreographer, but he’s a fine moviemaker as well, and Dirty Ho is one of his best. Even the shabby state of the print, an original from 1979 complete with curious purple splotches, seemed to pay tribute to three decades of campus film fanaticism. It could have played the Majestic.

Even with the loss of the two Hilldale screens, Madison has five commercial screens dedicated to foreign and independent films, not counting the Cinematheque and the Play Circle in the Student Union. Come spring with Sundance, we’ll get six more. And our Wisconsin Film Festival (April 12-15) comes hard on the heels of the Sundance complex. Wisconsin Movie Madness lives on.

DB

PS: Thanks to Ivo Blom for the Swarte illustration up top.

PPS 21 December: Today’s Isthmus has a nice story on Dan Fuller and the Wisconsin Bioscope company. I played a small role in their last film of the semester, and despite the need to wear eye shadow, this gave me an even greater appreciation of their efforts. They’ll have a screening of recent work some time next term.

Good Actors spell Good Acting, 2: Oscar bait

Kristin here–

David and I seem to be swimming against the stream of end-of-year blog entries. No ten-best lists, no predictions about Oscar nominations.

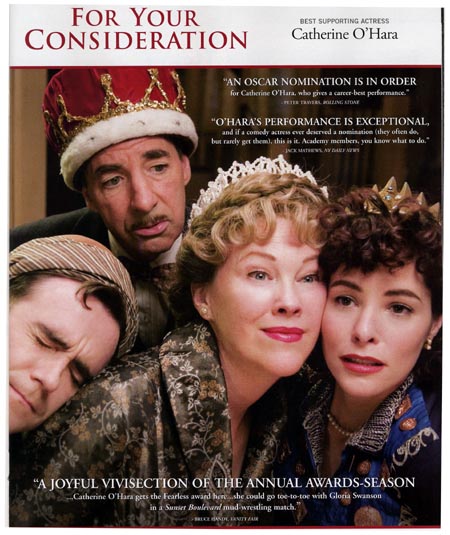

Instead, I’ll develop on the theme I introduced in my entry concerning the over-emphasis on star turns in reviews of films that contain an obviously outstanding performance. It’s interesting that quotes from such reviews are now routinely used in the “For Your Consideration” ads in show-business trade journals like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter when a studio is pushing a performance for award nominations.

There are a lot of good performances in any given year. We’ve all seen reviews that call a performance “Oscar-worthy” without the actor ending up getting nominated or even mentioned by pundits at year’s end predicting those nominations. Some types of performances just seem more like Oscar bait than others. What makes them that way?

Some of the reasons are apparent to almost anyone who pays any attention during the awards season. Notoriously, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences members prefer to honor dramatic roles rather than comic or musical ones. In 1985, a good deal of outrage was expressed—and rightly so–over the fact that Steve Martin was not nominated for his hilarious turn in All of Me. Conversely, the nomination of Johnny Depp for a comic role in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl created a stir, though few probably thought that he would actually win. (Remember, just being nominated is an honor, as nominees—and who would know better?—often point out.)

So, actors tend to be nominated for serious roles. Not just any kind of serious roles, though. History teaches us that playing a real person gives one’s chances for a “nod” (as nominations are for some reason now called). From Paul Muni in The Story of Louis Pasteur to George C. Scott in Patton to Ben Kingsley in Gandhi to Phillip Seymour Hoffman in Capote, it’s a familiar pattern. In the television age, when famous people’s appearances and behaviors are often familiar to the public, performances can become in part a matter of impersonation, and a skill at mimicry becomes a strong signal of “good acting.” Undoubtedly a performance like Helen Mirren’s as Elizabeth II in The Queen adds subtleties that go beyond the imitation of appearance and speech patterns and other obvious characteristics, but it’s the impersonation that gets talked about more.

Even when we’re not familiar with the person a character represents, for some reason it helps to have “based on a true story” attached to a title. Publicity often stresses that the actor met and spent time with the real person in order to craft an authentic performance.

Obviously making oneself less attractive to play a role gets Brownie points in a big way: Robert DeNiro gaining 60 pounds to play boxer Jake La Motta in Raging Bull, Charlize Theron sacrificing glamor in Monster, Nicole Kidman sporting an unflattering fake nose as Virginia Woolf in The Hours.

Characters with disabilities can definitely put an actor into the Oscar-bait realm: Cliff Robertson in Charly, John Mills in Ryan’s Daughter, Daniel Day Lewis in My Left Foot, or Jack Nicholson in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Presumably the implication of playing a real person or gaining weight for a role or simulating a disability all imply work, harder work than “just” playing a healthy, good-looking fictional person.

There are other indicators for nomination likelihood.

It helps to be old. Think Helen Hayes in Airport or Art Carney in Harry and Tonto. Their best performances? This year Peter O’Toole may finally get a non-honorary acting statuette.

It helps to be English and to have done Shakespeare.

For that matter, it helps to speak English. We’ll see if Penélope Cruz ends up being one of the very few to succeed without doing so. She did get nominated for a Golden Globe for Volver, but foreign-language films are definitely an afterthought when it comes to Academy Awards.

It helps to be Meryl Streep, whose performances don’t even have to fit any of these tendencies.

Oddly enough, most of these generalizations don’t seem to apply as much to the supporting-actor categories. Presumably “supporting” implies a less bravura turn that doesn’t compete with the stars.

Of course there are all sorts of reasons why actors get Oscars. A lot of people were surprised in 1997 when Juliette Binoche (The English Patient) beat out Lauren Bacall (The Mirror Has Two Faces) as Best Supporting Actress. It helps to recall that three years earlier, through a technicality, Binoche had been judged ineligible to be nominated for Best Actress in Three Colors: Blue. The injustice of that clearly rankled Academy members (the majority of whom are actors), and the first time they had a chance to make it up to Binoche, they did. Both Jimmy Stewart and Denzel Washington supposedly won their Best Actor awards because voters felt they had deserved them for previous roles.

On Thursday the Golden Globes nominations were announced. Reporting on the Globes tends to center around their predictive powers for the later Academy Awards. (See “And … They’re Off!” in the new Entertainment Weekly.) The Globes are just as interesting, though, for the fact that they divide the main film-acting awards into two categories: “Drama” and “Musical or Comedy.” (Two parallel best-picture awards are given in these categories as well, but for some reason the supporting-actor awards aren’t divided by genre.) So Sacha Baron Cohen and Johnny Depp can get nominated for comedies and not have to compete against Will Smith and Forest Whitaker in dramas.

If you like endless speculation on nominees-to-be, check out the December 2006 Hollywood Reporter issue “The Actor.” In it Stephen Galloway talks about actors playing real people: “Whether a story surrounding a character is biographical or fictionalized, actors are determined to find the truth behind their real-life role models” (“As a Matter of Fact”). Part of the reason that the trade press devotes so much space to awards speculation is because these special issues sell lots of “For Your Consideration” ads. This year my favorite one touts Catherine O’Hara as best supporting actress. They don’t even have to tell us the title.