Make mine music, not to mention pictures

Tuesday | October 9, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

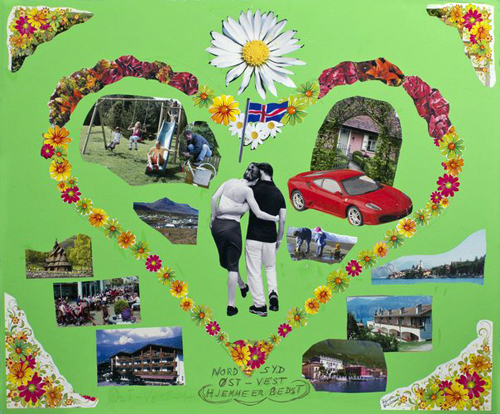

Collage by Sigrídur Níelsdóttir.

DB here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival has had strong commitments to certain types of cinema–Asian, Canadian, environmentally-sensitive documentaries, and perhaps least well-known, arts documentaries. I still recall seeing The Red Baton, a vivid account of Russian musical life under Stalin, at my first VIFF visit in 2006, and ever since I’ve tried to check out at least a few entries in this category. They’re not usually very daring formally, but they do open up areas of the arts that I cherish, and–just as important–areas I’m completely unaware of.

Childhood and the morning of the world

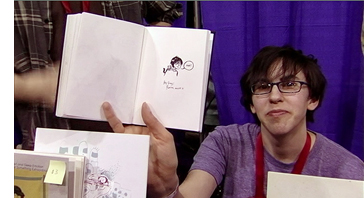

For instance, as an admirer of comic strips and comic books, I had to see Josh Melrod and Tara Wray’s Cartoon College. The institution in question is the Center for Cartoon Studies at White River Junction, Vermont. (Go here for the most educational college catalog I’ve ever seen.) Each year twenty students are admitted for the two-year MFA program, and the film follows several as they move through the curriculum.

Don’t be misled by the black clothes, Kool-aid hair, and cats’-eye glasses. These kids aren’t your usual Art School posers. They want to tell stories. Jen explores menstruation; Al, the 61-year-old Boston archaeologist, takes time off to learn to draw; and Blair the Mormon wants to chronicle his missionary work. Interviews with Lynda Barry, Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns, and Chris Ware are salted through this story of intense work, achievement, and occasional disappointment.

Don’t be misled by the black clothes, Kool-aid hair, and cats’-eye glasses. These kids aren’t your usual Art School posers. They want to tell stories. Jen explores menstruation; Al, the 61-year-old Boston archaeologist, takes time off to learn to draw; and Blair the Mormon wants to chronicle his missionary work. Interviews with Lynda Barry, Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns, and Chris Ware are salted through this story of intense work, achievement, and occasional disappointment.

One accomplishment of the film is to remind us of the very unusual qualities needed to be a cartoonist. There’s the patience of drawing hundreds of panels, and sometimes the same figure in hundreds of different postures, along with the hours of fine-grain line work and coloring. There’s also the sense that of all artists, cartoonists are most in touch with childhood, that period, as Ware remarks, when each experience is “rich and warm . . . and days seem to last for weeks.”

Perhaps that’s why the students radiate that awkward innocence that’s easily mocked. They explain how they didn’t fit in with their high-school milieu; one man recalls that people assumed he was either gay or a British exchange student “because I didn’t contract all my g’s and used proper English.” The great thing students find at CCS, says Spiegelman, is that “instead of being the outcast in art school you get to be with a bunch of other outcasts.” Yet these outcasts bond, forming couples and offering group critiques, and cooperating on projects for conventions and festivals. Cartoon College teaches you a lot about cartooning, but it also reminds you of the vitality of young imagination.

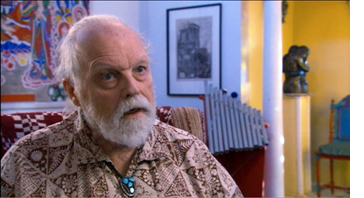

Lou Harrison, whom I knew chiefly as a pioneer of melding non-Western music with classical traditions, proved to be a fascinating figure in Eva Soltes’s Lou Harrison: A World of Music. This biographical account showed me that this man often considered marginal–far less well-known than Copland or Bernstein–in fact thrived at the center of the bohemian world of American music. He went to Mills College, taught at Black Mountain College, hung around with Henry Cowell and John Cage and Virgil Thompson, collaborated with Merce Cunningham and Mark Morris, and conducted the premiere of Ives’ monumental Third Symphony.

Harrison was open to every influence, from Schoenberg’s serialism to Harry Partch’s unorthodox instrumentation. He drew on Korean and Taiwanese music and Javanese Gamelan, and even composed pieces for Geiger counters (as a protest against nuclear testing). The result is music of great delicacy, with sumptuous textures and fluid melodies. Go here to listen to some samples.

Harrison was open to every influence, from Schoenberg’s serialism to Harry Partch’s unorthodox instrumentation. He drew on Korean and Taiwanese music and Javanese Gamelan, and even composed pieces for Geiger counters (as a protest against nuclear testing). The result is music of great delicacy, with sumptuous textures and fluid melodies. Go here to listen to some samples.

Like many of his peers and collaborators, Harrison was gay, and he wasn’t shy about saying so. The partner of his later years, Will Colvig, lovingly crafted unique instruments for his compositions. After Colvig’s death, Harrison struggled to put onstage Young Caesar, a gay-centered opera–for puppets, no less. “Lou was always out of fashion,” reflects conductor Michael Tilson Thomas. Unfashionable or not, Harrison left us music of pulsating lyricism and quiet, unforced radiance. The film’s celebration of this American original deserves wide circulation. Now a personal request to Ms. Soltes: How about Alan Hovhaness next?

Nordic thaws

Then there were two films that opened my ears. I wasn’t prepared for the brawny music of Kimmo Pohjonen, who is on roaring display in Kimmo Koskela’s Soundbreaker (aka Ice Bellows). Along with street mimes and face-painters, accordion playing has become a bad joke, but Pohjonen makes it a contact sport. Built like a torpedo, with short hair razored to a cellbock edge, he plays his amplified squeezebox like he’s grappling with a python. Our musician is first shown tramping across a frozen lake and then plunging through a hole before taking up his instrument and playing underwater.

It’s a nice introduction to Extreme Music, Finnish style. Thereafter, a mixture of concert footage and daily routine takes us into a world like Lou Harrison’s, where any sound can become music. Pohjonen will solo with the Kronos Quartet or with chugging farm machinery (the clip is here). Soundbreaker was the first film I saw in my VIFF visit. After hearing this infectious wahoo music, I ordered some albums. Consider doing the same.

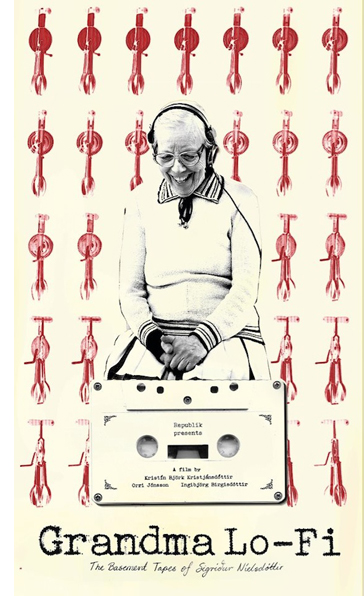

Speaking of Nordic revelations, there’s Grandma Lo-Fi: The Basement Tapes of Sigrídur Níelsdóttir. I can’t do better than quote the VIFF catalog, describing a lady who

decided to become a musician at the unlikely age of 70. Equipped with little more than a cassette recorder, cheap keyboards, common household items, and an adventurous spirit, she crafted an astonishing 59 albums in a mere seven years and became a DIY icon for a generation of Icelandic musicians.

Since some of those musicians include ones I follow, like múm, I had to catch up with Sigrídur.

Born in Denmark to a German mother and Danish father, she learned a little piano as a child. Later, after her sweetheart was lost at sea, she left her parents and made her own way. Parts of her life are hazy, but she wound up in Iceland with several children. Having worked as a shopkeeper, dog-walker, and lacemaker, she settled in old age in a basement apartment, where she began composing at a keyboard she called her “entertainer.”

Born in Denmark to a German mother and Danish father, she learned a little piano as a child. Later, after her sweetheart was lost at sea, she left her parents and made her own way. Parts of her life are hazy, but she wound up in Iceland with several children. Having worked as a shopkeeper, dog-walker, and lacemaker, she settled in old age in a basement apartment, where she began composing at a keyboard she called her “entertainer.”

Thanks to a double-tape boom box, she could dub and redub her compositions, often reusing commercial audiocassettes discarded from her library. Her music and voice were garnished with animal sounds (including barking dogs and cooing pigeons) and kitchenware noises. Eggbeaters made good helicopters, cheese graters evoked shamisens, and tinfoil provided campfire sounds. “Everyone is free to use these things. I don’t charge.” Like the rest of us, she self-publishes.

She filled her apartment with religious images and awoke at 4:30 AM to pray and read the Bible. Music, she says, taught her what the Bible really means. When she couldn’t sleep, she chirped to the birds; for all she knew, she might have been swearing in bird-talk. After 687 original songs, some dedicated to friends and family, she abruptly stopped her musical career and turned to cut-and-paste art. Her collages, like her music and album graphics, display simple geometric structures overwritten by doodlish embellishments, marks of classic “naive” or “outsider” art. But now outsider art inspires everyone.

The film, by Orrí Jónsson, Kristín Björk Kristjánsdóttír, and Ingíbjörg Bírgisdóttir, mimics the low-tech quality of Sigrídur’s oeuvre with rashes of graininess, images reminiscent of 8mm and VHS, and some self-conscious animation and SPFX tableaus featuring pop artists indebted to her. But the film isn’t mocking this remarkable woman, who perpetually grins in modest pride. As she tells us, “I don’t think you can do any harm with songs like these, right?” Like Lou Harrison, who was composing in his eighties, Sigrídur easily rivaled the energy and passion of Pohjonen and the kids of Cartoon College. Art keeps you young, as if you didn’t know.

I learn from many VIFFers that Alan Franey, Festival Director and CEO, is the guiding spirit behind the festival’s commitment to arts documentaries, and particularly those focused on music. For this and many other things, Kristin and I owe him our thanks.

10 October 2012: Thanks to Olli Sulopuisto for a major correction; I had initially called Pohjonen an Icelandic musician. Thanks to Olli as well for correcting a misspelled name.

Young Caesar, opera by Lou Harrison (1971).