Archive for March 16, 2010

Film criticism: Always declining, never quite falling

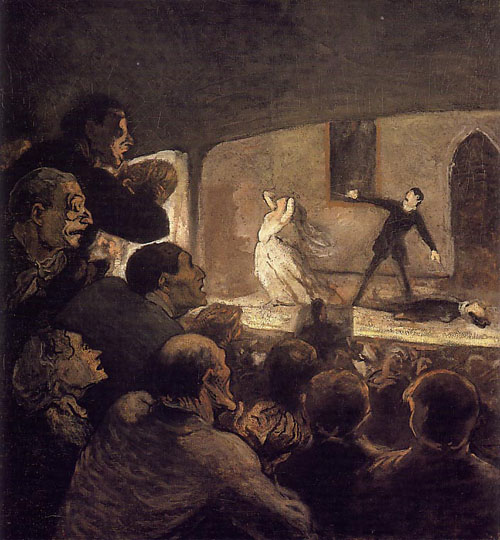

Daumier, Le mélodrame (1860-64)

DB here:

Before the Internets, did people fret as much about movie criticism as they do now? The dialogue has become as predictable as a minuet at Versailles.

Film criticism is dead.

No, it’s not! It’s alive and well on the Web.

Hah! Call that criticism? Nobody can be a movie critic unless they (a) write for print publication; (b) have been doing it for x years; (c) are a member of a critics’ professional society; and/ or (d) get paid for it.

Well, the track record of the official movie critics isn’t that great. Most of their writings are forgotten the minute they’re published.

Infinitely more awful is what you read on the Net. At least print critics kept up standards; there were gatekeepers (also called editors) and a literate public.

The result being….? When has a print critic of recent years equaled the greats of the past—Agee, Farber, Sarris, Kael?

Same thing goes for the Net. Blogs and websites don’t show me anything like that level of achievement. What I see is amateur hour.

Yeah? Well, bloggers and netwriters have passion!

But not a passion for using Spellcheck.

So if print criticism is so valuable, how come all those professional critics are getting fired?

Film criticism is dead.

Repeat as often as you like.

I thought I had watched this rondelay often enough from the wallflower section, but I got dragged onto the dance floor by Tom Doherty. In his piece for the Chronicle of Higher Education, Tom offered another eulogy for serious film criticism. Dead again, as Jim Emerson notes; killed by those wretched netizens.

To watch their backs and retain their 401(k)’s, most print critics have been forced into sleeping with the enemy. As a form of ancillary outreach, blogs, podcasts, and chat-room discussions have become a required part of the job description for print reviewers. Or maybe the print part of the gig is now the ancillary outreach.

Feeling the same heat, academic critics have also plunged into the brash new world. The film-studies panjandrum David Bordwell—think Knowles with chops in postmodern theory—runs one of the most closely watched blogs at David Bordwell’s Website on Cinema (http://davidbordwell.net/blog). The impact of the academic bloggers on Hollywood’s box-office gross is negligible (sorry, David), but the online work of the digital hordes is already making a substantial contribution to film scholarship—in the spirited parry and thrust of the dialogues, in the instant retrieval of past research, and in the factoid jackpots provided by the film databases.

I’m sure Tom means to be complimentary, but just to get mundane: No heat forced Kristin and me to the Web. I set up a bare-bones site in 2000, including a vitae and a statement about what studying film meant to me, because people were sometimes writing me asking for such information. Then, inspired by Philip Steadman’s stylish site extending the arguments in his book Vermeer’s Camera, I used mine to supplement my books, putting in corrections, second thoughts, and pictures. Then I began to write longish essays that build on things in the books.

When I retired in 2006, Kristin and I decided to recast the site as a supplement to our best-known book, Film Art: An Introduction. Our publisher McGraw-Hill funded an upgrade. But our efforts quickly went beyond spinning off the textbook. We treated Observations as our own magazine, with no pesky editors to tell us that a piece was too long or had too many stills. It offered a way to get our ideas out to a new audience, or maybe a bigger one. Just as important, after years spent writing books, I enjoy the recreation of writing shorter pieces. When you’re 62, sprints look better than marathons. Actually, because I’m a compulsive overwriter, some of my blog-sprints are like marathons.

Unhappily, none of this enhanced our 401(k)s.

Some other quibbles: Tom intended “panjandrum” as praise, but as many friends have pointed out, I’m probably the last person you’d associate with PoMo. I’m stuck in pre-post-modernism. Still, Tom is right on one point. My efforts to erode the box-office takings of Babel, The Departed, and The Dark Knight failed utterly. On the other hand, I may have considerably boosted Cloverfield’s first-dollar gross.

Nothing if not critical

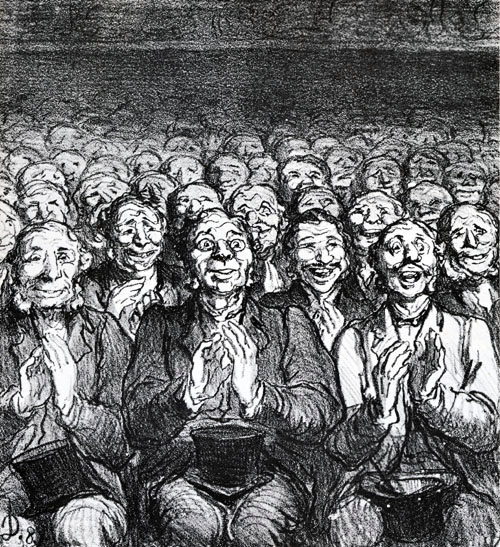

Daumier, Les critiques (1862)

Tom’s piece, its place of publication, the comments on it, and his reply to those comments invite me to revive some points I made around this season in 2008 and 2009. (Is it a rite of spring?)

Film criticism takes many forms. Tom identifies criticism with being paid to review movies that have just come out. This is a form of arts journalism, and like all journalism it is being squeezed by the decline in advertising revenue. So yes, print-based paid reviewing is waning.

But criticism includes more activities than rapid-response reviewing. It includes what we might call haute journalism, as practiced in literary quarterlies, film magazines like Cineaste and Cinema Scope, and even occasionally in the New York Review of Books (which just got around to noticing Sokurov’s 2005 The Sun). There’s also reseach-based criticism, published in specialized venues like Cinema Journal and in semi-specialized journals like Film Quarterly (which seems to be moving toward haute journalism). And of course academics have written whole volumes of film criticism—through-composed books, not collections of published reviews.

Each of these modes of criticism has its own conventions. I try to characterize them here. I think Tom should have made some of these distinctions, because it doesn’t help film culture to encourage readers of the Chronicle to limit their conception of criticism to what they get in The New Yorker or Salon.

Insofar as we think of criticism as evaluation, we need to distinguish between taste (preferences, educated or not) and criteria for excellence. I may like a film a lot, but that doesn’t make it good. For arguments, go here again. Criteria are intersubjective standards that we can discuss; taste is what you feel in your bones. A critical piece that merits serious thinking tends to appeal to criteria that readers can recognize, and dispute if they choose.

Enough with the love, already. My only real quarrel with Gerry Peary’s film For the Love of Movies is that it seems to place “love of cinema” at the center of the critical activity. But everybody loves film. The real question is: What does this love lead to? Gossip? Infighting and insults? A desire to take chances and watch films you might hate? A desire to stretch and nuance one’s viewing? An urge to learn something subtle about cinema more generally?

Opinions need balancing with information and ideas. The best critics wear their knowledge lightly, but it’s there. To be able to compare films delicately, to trace their historical antecedents, to explain the creative craft of cinema to non-specialists: the critical essay is an ideal vehicle for such information. The critic is, in this respect, a teacher.

Which means that the critic traffics in ideas too. A critic of lasting value offers a vision of cinema, of the arts more generally, of society or politics or something beyond the individual movie. For Sarris, the key idea was directorial authorship. For Parker Tyler, it was the idea that popular culture spasmodically threw up surrealistic material. For Farber it was the prospect that the studio system nurtured films, or moments, that hinted at speed, harshness, and darkness. Sontag clung to the hope that cinema could carry on the program of post-World-War-II modernism. For Ebert, what seems central is the belief that cinema can yield humane wisdom that forms a guide for living. Beyond our shores there were Arnheim, Bazin, Eisenstein (yes, he wrote film criticism), the Cahiers and Positif crews, and many more. Their powerful and provocative ideas yielded new ways to think about any movie.

Last year I moderated an Ebertfest panel consisting of a dozen or so critics. A student from the audience said he wanted to be a critic too. Instead of advising him to get into a more financially rewarding form of endeavor, like selling consumer electronics off the back of a truck, the panelists encouraged him. This form of altruism, in which you help people to become your competitor, is alarmingly common in the arts.

A moderator doesn’t get to talk much, so I couldn’t respond. What I wanted to say was: Forget about becoming a film critic. Become an intellectual, a person to whom ideas matter. Read in history, science, politics, and the arts generally. Develop your own ideas, and see what sparks they strike in relation to films.

Writing style is overrated. Many people think that good reviewing amounts to personal opinions whipped up in frothy prose. Perhaps the snazzy styles of Farber and Kael have led people to weight style too much. Granted, the Web has revealed that a lot of people are excellent writers, and without the Web they would probably never have found an audience. Although lively writing is always welcome, it gets heft and endurance through its arguments, and that comes back to ideas and information as much as opinion.

Hollywood, still declining

As often happens, a current controversy sends me backward, and to books. Ezra Goodman’s Fifty-Year Decline and Fall of Hollywood was published in the momentous year 1960, as was Beth Day’s This Was Hollywood. Both wrote finis to the glory days of American studio cinema. But if Day was nostalgic, Goodman was sour, and racy.

He worked as reporter, publicist, and reviewer, most notably for Time. By 1960, he must have felt he never needed an LA job again, so he castigates every specimen of Hollywoodite, from press agents to stars. Buddy Adler, who for a while ran production at Twentieth Century-Fox was no more than “a dutiful office boy.” Humphrey Bogart had “as a result of four marriages, innumerable bouts with the bottle, and a paucity of food and sleep developed what was described as a look of intelligent depravity. . . .”

Goodman includes a long chapter on film reviewers, which launches with a decidedly contemporary ring:

It has been said that there are sometimes more clichés in movie reviews than in the movies they are discussing. Sample review phrases: “sure-fire,” “stunning,” “taut with suspense,” “lavish and exciting,” “sumptuous,” “captures the imagination,” “moving,” “significant drama,” “sheer screen artistry,” “uncommonly good performance,” “dramatic urgency,” “enormous compulsion,” “spectacular finish,” and once in a while, “ineptly directed,” “singularly dull.”

Fifty years later, Goodman would have to add jaw-dropping, adrenalin-charged, mind-bending, hellish/ hellacious, resonance/ resonate, lush, dark, incredible, intensely personal, pitch-perfect, and our two all-purpose adjectives of praise, amazing and terrific. You’d think that we were staggering around astounded all the time.

Yet reading Fifty-Year Decline and Fall confirms my hunch that we have made progress. I would say that the best film writing in all registers–daily/ weekly reviewing, haute journalism, “think pieces,” personal essays, research studies, whether on the web or off– is much better today than it was in Goodman’s era. Then the New York Times had Bosley Crowther; now it has Dargis and Scott. Richard Schickel has hurt his reputation with some insulting remarks he made recently, but read his book on Fairbanks, His Picture in the Papers, or his scathing The Disney Version, and you’ll find a keen eye and a nonconformist intelligence. Riding above the oceanic fizz of infotainment, there are many sharp writers both journalistic and academic. Start clicking our link-list for examples.

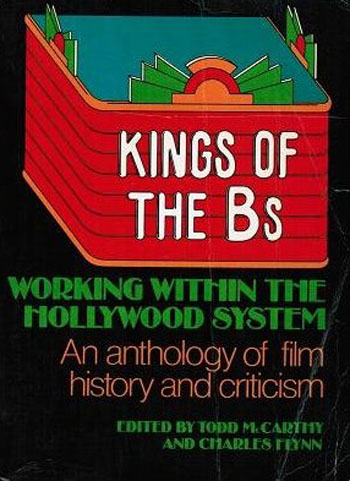

Which makes it all the more lamentable that two of our finest writers have lost their platform. Todd McCarthy’s work for Variety long exemplified the virtues I’ve itemized. He writes a brisk prose that isn’t showoffish. His reviews, often in a few deft words, situate the film historically; he’s one of those guys who has simply seen and read everything. He has as well a guiding idea of cinema—roughly, I think, the premise that straightforward classical storytelling is an inexhaustible resource—but he doesn’t deploy it as a bludgeon. McCarthy’s respect for studio history and the tradition of expressive narrative can be found in his and Charles Flynn’s indispensible collection Kings of the Bs (where you can see what a Republic budget sheet looked like) and in his biography of Howard Hawks. There are also his documentaries on filmmaking (e.g., Visions of Light) and film culture (Man of Cinema: Pierre Rissient), which allow him the leisure to probe subjects in depth.

Or consider Derek Elley. He is one of the most knowledgeable writers on Asian cinema, and his reviews skillfully tie a new film to a trend or earlier work by the same director. Few critics have his ability to supply a translation of a Chinese film’s original title, or to explain a crucial local custom. By dismissing McCarthy and Elley as contract writers, Variety has dealt a blow to informative, thoughtful film writing, whether you call it criticism or not.

Daumier, One says that the Parisians. . . (1864)