Archive for 2011

Cognitive scientists 1, screenplay gurus 0

Kristin here:

The annual meeting of the Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image is currently taking place at Elte University in Budapest. It runs from June 8 to 11. It must have started off very well. Barbara Flueckiger posted this comment on the opening keynote address on Facebook: “Just attended an absolutely fascinating and inspiring talk by Talma Hendler, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience: ‘Brain Shows Where the Drama Is. A Call for an Empirical Neurocinematic Agenda.'”

Last week David posted a new web essay on “common-sense film theory” as a way of participating from afar in the work going on in Budapest. Now it’s my turn to post a SCSMI-related item.

The mirage of the second-act desert

Twelve years ago I published Storytelling in the New Hollywood (Harvard University Press). It included a claim that most classical Hollywood feature films have four acts, lasting roughly 25-30 minutes each, adding up to a film of from 100 minutes to two hours. This claim ran counter to the old notion, popularized by Syd (Screenplay) Field, that Hollywood movies (and, according to Field, all feature narrative films) have three acts of 30, 60, and 30 minutes respectively.

My book analyses ten films in detail, dividing them into their four parts: Setup, Complicating Action, Development, and Climax (usually including an epilogue). I also have an appendix listing ninety additional films that I timed by large-scale part, ten for each decade from the 1910s to the 1990s. My conclusion was that most of these films stuck to the four-part structure with each part within five minutes either way of lasting a half-hour. Some of the exceptions were actual three-act films (e.g., Adam’s Rib) and others were longer films. Amadeus, one of my ten main examples, is 160 minutes long and has five large-scale parts. (“Large-scale part” was the rather cumbersome term I employed in the book, trying to avoid the misleading word “act.” I have to admit though, that there’s little chance of people discontinuing “act” and switching to “large-scale part.”)

I also defined the “turning point” that Field says divides acts more concretely than he does, specifying that it usually results from moments when the main characters formulate or modify the goals that drive the narrative forward. (I expand upon the relationship of goal shifts and turning points in a previous entry.)

Unlike Field and other screenwriting “gurus,” I allow for exceptions to my four-part schema. The Pink Panther doesn’t have a turning point until over 52 minutes in; the lengthy early part of the film consists of a bedroom-farce situation of male sexual frustration that makes absolutely no progress toward the putative subject of the film, the theft of a valuable jewel. As far as I can tell, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World has no turning points at all. I remember thinking it was quite funny when I saw it as a child.

Some screenwriters have read the book, and some who teach screenwriting courses assign it as a textbook. At least it’s still in print, which is something to be grateful for at my age.

Since the book was published, it certainly hasn’t knocked out the conventional view that films have three acts. Not infrequently I read a review in Variety or another specialist journal that refers to the last quarter of the film as the “third act.” The idea that films fall into chunks lasting 30 minutes, 60 minutes, and 30 minutes, no matter how counterintuitive or inaccurate, is too entrenched to be dislodged, apparently.

Still, I have the consolation that I’m apparently right. Other people have tried out my claim and found it to work. Creative Screenwriting gave a very kind review to my book (in its March/April 2002 edition, not online). D. K. Holm, the reviewer, was inspired to test out my system on the next three films he saw in theaters. He declared that it worked as predicted for The Shipping News, In the Bedroom, and even Ali, a five-act film. (My claim is that longer films don’t stretch their four acts. They add more, roughly 30 minutes long, for every half hour beyond the standard two-hour feature. Roughly half an hour apparently seems to create a pleasing balance as far as Hollywood practitioners are concerned—whether they’re aware of it or not.)

Real scientists at work

Now James E. Cutting, whom we enjoyed meeting and talking with at last year’s SCSMI conference (David devoted part of his report on the conference to James’s work), has collaborated with two of his graduate students, Kaitlin L. Brunick and Jordan E. DeLong, on a quantitative study related to Storytelling. They set out to test the whether the four large-scale parts of a classical film are reflected on the stylistic level. Specifically, do shot lengths and the use of non-cut shot transitions (fades, dissolves, and the like) vary in a patterned way across or among the parts?

It’s exciting to see cognitive scientists study claims that I’ve made on the basis of close film analysis. David has had his claims about staging and attention in There Will Be Blood confirmed by Tim Smith’s eye-tracking research on the same sequence. Now the results of Cutting, Brunick, and DeLong’s work relating to the four-part structure have been published in Projections (Vol. 5, issue 1, Summer 2011), subscriptions of which are included in SCSMI membership. Luckily I didn’t know this article was on the way, or I might have been in some suspense to find out whether my model worked. (This and other articles on film are also available online, linked from this page that lists the work on film published by James and his colleagues.)

As the authors’ starting point, they accepted my four-part structure. Or as they put it:

We find Thompson’s argument persuasive and her data remarkably clean. Nonetheless, the division into acts is built on a detailed analysis of the narrative, and we work from the physical properties of film. Many observers might agree on act divisions, but these divisions would not necessarily be reflected in any physical measure of a film’s shots and transitions. Thus, without prejudice as to what we might find, we sought data in shot lengths and in shot transitions that might corroborate Thompson’s analysis. (p. 4)

The team used 150 films they had previously studied in their work on editing patterns and their possible correlations to human attention. Of these, some were eliminated because they were too long, so that the statistical work could concentrate on films with four parts. I cannot claim to be able to follow all the statistical manipulations the data from these films were put through—though I can tell from the information in the footnotes that the degree of probability for some of their results indicated an amazingly small chance of error.

The figure at the top is a “scatter plot” of shot lengths for 143 Hollywood films from the period 1935 to 2005. These figures have been statistically adjusted in ways that allow the films to be compared despite their differing lengths. (I have no idea how this sort of thing is done. You’ll have to see the explanation in the article.)

One striking revelation of this chart is that the lengthiest shots in the films occur at the beginning, end, and at the one-quarter, two-quarter, and three-quarter points. Moreover, the “scallop” pattern of rising and falling average shot lengths shows a “tendency toward intensification of films near the middles of acts, where shot lengths become slightly shorter.” The ASLs were found to be as much as 1.1 seconds shorter than in the early and later portions of the acts.

Luckily I was right about the four parts. But beyond that the authors came up with results supporting my claims about the functions of the plot’s third part, the Development. Here’s how.

As part of the study, the authors tackled the question of where non-cut shot changes fall in relation to the quarters of films. Non-cut changes are fades, dissolves, and the like. It turns out, not surprisingly, that quite a few of them come early on, since the exposition may move among time and places setting up the basic premises of the narrative. But the rest tend to come in the third quarter, the Development. That makes sense to me. By my definition, the Development is essentially the stretch of action where most of the major premises, goals, and obstacles have been established. Before the climax can begin, the protagonist usually struggles against obstacles, usually provided by the antagonist. Often relatively little happens in the Development to forward the action, at least in comparison with the other three parts. At the Development’s end, some vital last premise is introduced that allows the action to move into the climax portion, where the plot moves forward relatively quickly and no more major premises are introduced.

The Development might contain extra fades and dissolves for two reasons. First, a surprising number of films have a montage sequence shortly after the middle turning point. The one depicting Michael Dorsey’s rise to fame as Dorothy Michaels in Tootsie is one such. Second, since the Development often is the section where time passes until the point where the climax can begin, one would expect fades or dissolves to cover temporal gaps. I’d have to go back and watch a bunch of films to confirm those hunches, but they seem logical.

My main purpose in writing Storytelling in the New Hollywood was to show that the principles of classical narrative construction formulated in the 1910s and used throughout the studio era are still operative today. Despite film reviewers’ complaints that action and special effects have come to substitute for story appeal in modern mainstream films, the kinds of films they find so shapeless do usually stick to the same four-part structure, contain goals and conflict and the rest of the principles that have been in effect for decades. Cutting, Brunick, and DeLong’s work bolsters this claim about classical narrative’s stability over time. They find that “there are no obvious differences in these patterns for films of different eras.” (p. 8.)

This issue of Projections has other articles applying a cognitive-science approach, and with luck future issues may contain some of the papers we have been unable to attend at this year’s conference.

James, Kaitlin, and Bradford have set up an online overview of their research in progress, “Shot Structure and Visual Activity: The Evolution of Hollywood Film.” The graphics and type are quite small, but right-click on the page and click “Marquee Zoom,” which brings up the little magnifying glass that allows you to enlarge it multiple times.

For online applications of the idea of four-part structure, see David’s essay on Mission: Impossible III and his blog entry on Source Code.

Jordan DeLong, Kaitlin Brunick, and James Cutting at annual convention of SCSMI, Roanoke 2011.

Chinese boxes, Russian dolls, and Hollywood movies

The Locket.

DB here:

In the 1990s and 2000s, American cinema was hit by a rash of fancy storytelling. Filmmakers experimented with flashbacks, replays, shifting points of view, multiple universes, network narratives, and a host of other unusual devices. (Some prototypes: Pulp Fiction, The Usual Suspects, Memento, and Short Cuts.) These developments nudged me into analyzing the trend in The Way Hollywood Tells It, but my interest in such tricky narration goes back to my adolescent love of detective fiction and the stories of Henry James, Faulkner, and James Joyce. For me, mysteries and modernism went together.

That was especially true of 1940s movies, which I now realize loom large in my film consciousness. Many of the fractured, densely plotted movies I wrote about at length in Narration in the Fiction Film, such as Murder My Sweet, The Big Sleep, In This Our Life, and The Killers, come from the same era as Citizen Kane and How Green Was My Valley. So do subjects I wrote about later, such as Mildred Pierce and Rope and network pictures like Weekend at the Waldorf and Tales of Manhattan.

This summer I face up to my proclivities and give a batch of lectures under the rubric “Dark Passages: Storytelling Strategies in 1940s Hollywood.” The series, accompanied with ten screenings, is part of a “Film College” to be held in Antwerp under the auspices of the Flemish Service for Film Culture and the Belgian Cinematek. I first wrote about this “summer movie camp” here. I probably shouldn’t have called it that; I still get emails from services that sell canoeing gear and organize outings to the Poconos.

Starting to think about this course has given me more ideas than I can pursue in seven lectures, so in the weeks to come don’t be surprised if some chips from the workbench get swept up here. Even if you merely like the 1940s for those gleaming cigarette cases and those fashion shoulders that seem to have been designed with a carpenter’s level, we can enjoy some rather tricky pieces of movie storytelling.

The inner circle

During the early 1930s American studio filmmakers experimented considerably with flashbacks. (I write about that trend here.) Several associated conventions, such as the dissolve-plus-music, as well as the track-in to a narrating or remembering character, seem to have been installed then. But in the 1940s, the flashback became a more wondrous thing.

Relatively rare in the later 1930s, after a few years the technique seemed to be everywhere. You’d expect that Citizen Kane might have set the fashion, but at least eleven other pictures from 1941 boasted flashbacks. A year earlier, Sturges’ The Great McGinty had built its plot around the device and John Farrow’s Married and In Love crammed six flashbacks into less than sixty minutes. Soon critics, those chronic malcontents, protested. In 1944, the Los Angeles Times reviewer Philip K. Scheuer wrote of Double Indemnity, “I am sick of flash-back narration and I can’t forgive it here.” One producer claimed that “the market is glutted with flashback pictures,” and had alternative scripts of The Chase (1946) written to allow the editor to omit the original novel’s flashback. Since the late 1920s, flashbacks had been staples of courtroom dramas, but by late 1948 a reviewer expressed relief that in The Paradine Case (1948) “There are no flashback devices to clutter the trial.”

As flashbacks proliferated, they got weirder. Films gave us flashbacks retelling events from different characters’ perspectives, flashbacks that proved deceptively incomplete or downright false, even flashbacks narrated by corpses. Then there was the embedding option: setting a flashback within an already-established flashback.

Here’s an example. In Shoot to Kill (1947), Marian Dale is brought into the hospital from a car crash and is pumped by a reporter anxious to get her story. The narration flashes back to happier times, when the reporter introduced Marian to Larry, the new district attorney. When Larry takes her to dinner, Marian explains how she came to find him attractive. Now a further flashback shows her listening raptly to Larry’s aggressive prosecution of the case against mobster Dixie Logan. Coming out of this flashback, we’re back in the restaurant, and flirtation continues between Marian and Larry. At later points we’ll come out of that earlier time frame back to the present, with Marian and the reporter in the hospital.

This sort of embedding is an obvious option, but let’s go to the next level. What about a flashback within a flashback that’s already nested inside another flashback? Or even, gulp, flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks? Do the math. The result is like the famous Chinese boxes or Russian dolls, with one story held within another, which is held within another, and so on.

Many of the strangest narrative experiments of the 1940s are to be found in B films. Perhaps in that domain the demand for novelty and rapid turnover is greater and the constraints on plausibility, or even just good sense, are fewer. Shoot to Kill, an independently produced B-item, would seem to be an example, though it’s not as wild as The Sin of Nora Moran (1933), my candidate for America’s most peculiar flashback movie. Surprisingly, though, the multiply-embedded flashback is most prominent in two high-profile films of the 1940s.

How could I talk about them without spoilers?

Marseille or bust

Flashbacks are often presented as solutions to a mystery: we go back to the past to learn how or why something took place in the present.

Passage to Marseille (1944) opens with Manning, a war correspondent, visiting a camouflaged air base in the English countryside. From here Free French pilots launch bombing raids on Germany and occupied France. Struck by the intensity he sees on one gunner’s face, Manning asks his host Freycinet about the man’s past. Freycinet answers with “the story of a little group of whom Matrac was one.” That is the first layer, or the surrounding box.

Aboard the Ville de Nancy: We go back a few years to a French cargo ship carrying nickel ore to Marseille. Freycinet, traveling on orders, runs into conflict with the right-wing Major Duval and his coterie. The ship rescues five men from a drifting boat. Are they prospectors, as they claim? Soon Freycinet realizes that they are convicts, escaped from Devil’s Island. They start to explain how and why they got away.

Devil’s Island: We see the men plan to escape, but these convicts don’t simply want freedom. They are patriots who yearn to fight the Germans. But one, Matrac (Humphrey Bogart), sits apart from the others and won’t explain himself. Why? Another member of the team, Renault, explains.

France, 1938: Daladier returns from Munich with news of an accommodation with Hitler. Matrac, a crusading reporter, is disgusted and writes scathingly of this sellout to Nazidom. His newspaper office is smashed by right-wingers while police and citizens look on. Disabused of his faith in France, Matrac seizes the chance to flee with his lover Paula. But he is arrested, tried on trumped-up charges, and sent to Devil’s Island.

Devil’s Island: After Matrac has been let out of solitary confinement (where he shouted, “I hate France!”), the five men escape from the prison camp. The old man who helps them asks only that they promise to serve French freedom. But Matrac refuses to recite the pledge (above). The new mystery becomes: What has turned him into the loyalist gunner that Manning sees in the opening scene?

Aboard the Ville de Nancy: On the ship, word comes that Marshall Pétain has signed an armistice with the Germans. The captain secretly swerves the ship from Marseille, a Pétain-controlled city, and sets sights on England. But his ruse is discovered by Duval, whose men seize the ship. A fight ensues, with the crew and the Devil’s Island brigade pitted against the pro-German officers. Soon a German bomber arrives to sink the ship, but only after Matrac assures the dying cabin boy that they will drive the enemy out of France.

Back in the frame story, all mysteries from the past have been cleared up. Now Manning appreciates what the pilots have sacrificed, and he understands what has turned Matrac back into a patriot. The film could close quickly, but the plot sets up a new future-oriented suspense. Manning and Freycinet wait for the planes to return from the night’s bombing run. Renault’s plane, though, is delayed, and it brings back a fatally wounded Matrac. This time he has not been able to drop a message to Paula as his plane passes over their farm, but at Matrac’s funeral, Freycinet assures everyone “That letter will be delivered.”

In Passage to Marseille, Matrac’s 1938 adventure forms the core, wrapped in three layers. We have a flashback within a flashback within a flashback, itself surrounded by a frame story set in the present. The whole action takes place across about six years. Why tell the story in this complicated way?

Because, I think, it enhances mystery. The initially formulated mystery is vague, revolving around Manning’s inquiry about the charismatic Matrac, but other questions get more specific. What led these five men to near-death on the open sea? Are they really gold prospectors? Why does Matrac sit sullen while his comrades explain their patriotism to Freycinet? What has made him so bitter? And since we know from the start that he has become a committed patriot, what led him away from his solitude? These aren’t the sorts of questions you get in a classic detective story; they focus on personal psychology and character change. A more linear story tends to give us motives straightforwardly, and it explicitly traces the process of people changing their minds and hearts. The broken timeline creates more curiosity as we are led to ask why people do what they do. These are puzzles of personality.

The film thus gains a double propulsion. We have the usual forward movement, the rhythm of anticipation hinging on the question: What will happen next? But the mystery element adds curiosity about the past, asking: What led up to the situation of crisis that we see now? This double movement is seen in many 1940s films, which in retrospect (my own flashback here) may be one reason I turned to that era in exploring storytelling options in my narration book.

Hopelessly twisted

When we encounter embedded flashbacks, the plot often treats the core, or innermost layer, as the ultimate secret, the source of what teases us in other layers. Like Passage to Marseille, The Locket (1946) turns on a puzzle of character: Is the beautiful and charming Nancy exactly as she seems? We find out when we witness a childhood trauma located in the center of the plot’s geometry.

It’s the wedding day of John Willis. While his dazzling bride-to-be Nancy beguiles the guests, John is called away to meet Dr. Blair in his study. Dr. Blair has come to warn him: Nancy is “hopelessly twisted.” He explains….

Some years earlier: Nancy and Blair meet, fall in love, and marry. With a lovely wife and a flourishing psychiatric practice, Blair couldn’t be happier, but one day a young artist, Norman Clyde, visits his office. Norman tells him that Nancy could be charged with murder, and she must act to save the life of a man about to be executed (image above). He explains….

Earlier: Nancy is visiting Norman’s studio for an art class, and soon they’re involved in a romance. Her boss Andrew Bonner is a patron of the arts, and she calls his attention to Norman’s work. After a party celebrating Norman’s recent success, Norman finds that Nancy has stolen another guest’s expensive bracelet. He asks her why she did it, and she explains….

Childhood trauma: Nancy is ten, and her mother works as a servant for a wealthy family. The daughter of the house, Karen, is Nancy’s best friend. Karen gets a diamond locket for her birthday, but she gives it to Nancy. When her mother finds out, she takes it back and upbraids the girl. Later Karen’s locket is missing. Although it simply went astray, Karen’s mother brutally forces Nancy to confess that she stole it. Nancy and her mother are dismissed from the household.

Back in Norman’s studio, he points out that Nancy’s stealing the bracelet at the Bonners’ party was her effort to get even with Karen’s mother. Nancy swears to never steal again, and he anonymously mails the bracelet back to its owner. Later, at another art-crowd party at the Bonners, Norman is looking for Nancy when he hears a gunshot. Upstairs, he finds Nancy running down the corridor while a maid discovers Bonner’s body. Later, Nancy denies killing her boss, and Norman agrees to conceal what he saw. But he’s tormented by the fact that a manservant is now the chief suspect. Claiming that he’s too suspicious of her, Nancy breaks off their affair.

Back in Blair’s office, Norman begs Blair to induce Nancy to confess and save the servant, who’s to be executed tonight. Norman visits Blair and Nancy, who admits their old affair but denies killing Bonner. The next day, with the servant now executed, Norman flings himself through Blair’s office window and falls to his death. Shaken, Blair returns to England, where he and Nancy take up the war effort. When a bomb is dropped on their own street, Blair searches the rubble of their apartment and finds jewels that have gone missing from the collection of an acquaintance. Nancy turns up unharmed, but Blair has a breakdown and Nancy leaves England.

Back at the wedding: John remains skeptical, especially after Nancy comes in. She smilingly admits knowing Blair, but says he was only her psychoanalyst. She points out that he cracked up in London and was recently released from an asylum. Having renewed John’s trust, she goes to meet his mother, revealed as well to be the mother of Karen, her playmate of long ago.

We now understand that Nancy is marrying into the family that had cast her out as a child. Karen has died, and her mother fastens Karen’s treasured locket around Nancy’s neck. Trying to brazen through the ceremony, Nancy is assailed by memories of her childhood and her crimes. She becomes dizzy, screams, and faints. As she’s taken to a sanitarium, John decides to go with her, adhering to Blair’s last bit of advice: “Lockets are only symbols. It’s love she needed–and love she needs now.” Maybe she isn’t as hopelessly twisted as he had initially said, or as the plot itself seems to be.

Hitchcock’s films Spellbound and Marnie saved the revelation of childhood trauma for the climax, but The Locket doesn’t do that. Nor does the scene come at the exact center of the running time, as the plot geometry might suggest. The childhood scene arrives at the sacred twenty-five-minute mark, after Nancy’s confession to Norman that she stole the bracelet at the Bonners’ party. The plot thus emphasizes the aftershocks of Nancy’s childhood, creating suspense about whether she can continue to hide her trauma.

Someone versed in modern literature might ask: But can we be sure that we now know her trauma? Her confession to Norman is embedded in the tale Norman tells Dr. Blair. He is a somewhat unbalanced fellow, rude, proud, and inclined to do rash things. “Why,” he asks in his voice-over, “was I always throwing away the very things I wanted?” And of course his tale is embedded within the story Blair tells John Willis, the prospective bridegroom. By the end of his time with Nancy, Blair is a nervous wreck; he could be delusional. In literature, we might well suspect a trauma that has made its way through three filters (adult Nancy-Norman-Blair).

This possibility is accentuated by the film’s unusual adherence to each character’s range of knowledge during each flashback. We know pretty much only as much, in turn, as the child Nancy, Norman, and Blair know. Most classical flashbacks roam more freely outside the recounting or recalling character knew, or could have known. The Locket‘s restriction to each man successively optimizes the mystery of grown-up Nancy. But the strategy also offers no outside validation that what each man tells us actually happened. With no external or objective scenes of Nancy doing vicious things, the film locks us within what could be wholly hallucinatory tales.

Classical Hollywood film doesn’t try to undermine us so thoroughly, though. However modernist the multiple-narrator format of the film looks, the implications for reliability aren’t as unsettling as in literary works like The Sound and the Fury. The conventionally realistic style of most of the film makes it difficult for us to imagine layers of lying. We’re most likely to take what see and hear as veridical, unless there are explicit clues (as in, say, the landscapes and plot twists of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) to ask us to ask whether what we’re seeing is unreal in the fiction. What actually ensues is a drama of crafty concealment. As the evidence piles up against her, the question becomes: How will Nancy outwit her man this time?

This maneuver is especially significant in the film’s last third, when Blair suspects that she has stolen jewelry from Lord Windham’s collection. He tries to peek into her purse, but when she finally shakes out its contents, the missing locket isn’t there. He is relieved, though his suspicions continue to prey on his mind. We have to wait too, but when Blair finds the necklace in the apartment wreckage, we’re hardly surprised. Everything we see has been actual; we must doubt Nancy, not the narrators.

A ghastly melodrama

Even in the men’s stories, the film drops a few hints that Nancy isn’t what she seems. At one point, the camera lingers on her after Blair has left her in their London apartment. As she closes the curtains for the blackout, she crouches and looks askance in the classic posture of the guilty one. (On re-viewing, we might take this as suggesting she was looking off at the real hiding-place of Lord Windham’s locket.) Earlier, when she starts to tell Norman of Mrs. Willis’ abuse of her, she turns from him and looks at the camera, as if asking us to believe her.

Above all, there is the linkage of Nancy with Cassandra, the suffering madwoman of Greek mythology who was notoriously ignored by those she tried to warn. She had the gift of prophecy, but that quality seems denied Nancy. The prophetess we meet in the movie is a horoscope reader at the wedding, and she supplies banal and contradictory predictions. More telling, and spooky, is the fact that the Cassandra of the film is seen in Norman’s painting, and her eyes are filmed over, blank and presumably blind. This image is counterposed to the portrait Norman later paints of Bonner’s wife. She is confined to a wheelchair but on the canvas, she is presented as majestically erect and possessed of a penetrating glance.

The blind Cassandra seems scarily oblivious to her madness, while this painted mother-figure seems all-seeing. It’s no great reach to consider her a variant of Karen’s mother, who tormented the young Nancy and who comes back at the end as another, less serene incarnation of Norman’s second painting.

In sum, the prophetic quality of the heroine’s namesake is taken over by the film’s overall narration, which makes sure that everything that is planted early (the locket, the painting, a music box, the mean Mom) comes back with a relentless logic at the end.

But we shouldn’t forget that the Cassandra of legend was repeatedly raped. If she’s mad, men helped make her that way. The film is as much a study in male neurosis as in female frailties. Behind the swagger and insults, Norman is insecure, and he ends his life spectacularly. Earlier he had told Nancy: “If I had to relive these past few weeks, I’d kill myself.” As for Dr. Blair, on the strength of a single encounter, he smugly diagnoses Norman as “a paranoiac with guilt fantasies.” Yet he forgets that Norman told him about the partygoer’s missing bracelet, as if his wife’s childhood loss of the locket erased his awareness of what led her to tell it. After a few years with Nancy and the blitz, he’s the one who ends up in an asylum.

Unlike the stalwart heroes of Passage to Marseille, Nancy’s men trace no smooth character arc. The fragments given us in Passage can be swiftly reassembled. We understand that characters can change, and we expect that the film will trace out the men’s survival, especially after the opening establishes their successful bombing missions. We also note that Matrac is played by Bogart, and anyone who caught Casablanca (released fifteen months earlier) could see his change of heart coming from far off.

In The Locket, the failure of the men to understand, let alone heal, Nancy is made explicit when she tells Blair about a film she’s just seen. “I’m all goosepimples.” “A melodrama?” he asks. (We need to recall that in the 1940s that term was often applied to crime films and thrillers.)

Nancy: Yes, it was ghastly. You ought to see it, Harry. It’s about a schizophrenic who kills his wife and doesn’t know it.

Blair, laughing: I’m afraid that wouldn’t be much of a treat for me.

Nancy: That’s where you’re wrong. You’d never guess how it turns out. Now it may not be sound psychologically, but the wife’s father is the–

Blair: Darling, do you mind? You can tell me later.

Nancy’s father, she told Norman, was a painter like him, but he failed, and he is already dead when we see her as a child. In the popularized Freudianism of the 1940s, perhaps Nancy lacks the firm guidance of a strong male; certainly her kindly but ineffectual mother isn’t much help to her. But then neither are these supposedly grown-up men.

Risks and rewards

During Nancy’s hallucinatory march to the altar, music and dialogue and visual moments from earlier in the film collide and overwhelm her. But this is merely the climax of the inward bent of The Locket as a whole, which contains almost no exterior scenes. We might be tempted to attribute this interiority to the old standbys, wartime trauma and postwar malaise. The subjective sequences could be put down to the resurgence of Expressionist style, purportedly under the influence of German directors and technicians who fled to Hollywood. So far, so familiar.

I’m inclined to see a different dynamic at work. What if the stereotypes of situation and imagery sprang not from a Zeitgeist or localized influences? What if current themes and trends were exploited by filmmakers aiming for a more complicated sort of storytelling that still adhered to the models given by tradition? For reasons I hope to explore in my lectures and in some blog jottings, I think that many American filmmakers aimed more or less deliberately to revise Hollywood narrative norms in fresh, sometimes startling ways. In their urge to shake up their audiences, writers, directors, and others competed in pushing the envelope, straining the premises further as the decade went on. Why not a blind Cassandra or a mixup of mother-figures? Why not tell a story from a corpse’s point of view?

This enterprise gave us many fresh, even shocking films, but they risked incoherence. You see it in the resort to amnesiac heroes, to savage dreams, to perfunctory or downright inconsistent endings, to angels who might rescue us, to moments that repeat or condense or contort other images scattered across the movie, like the queenly mothers and blind prophetess of The Locket. When a producer is ready to leave decisions about flashbacks to the editing stage, you shouldn’t be surprised by gaps and disparities.

Still, even if a movie gets hopelessly twisted, it can provide a creative play with storytelling options. Or so I’ll try to show from time to time in the next few months.

An earlier entry discusses the cycle of early-1930s flashback films. The quote from Philip Scheuer comes from James Naremore’s subtle and informative More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts, 2d ed., 2008, 17. The quotation from Seymour Nebenzal, producer of The Chase, appears in “Hollywood Inside,” Variety (16 September 1946), 2. The finished film did drop the novel’s flashback, but something more peculiar was put in its place. (That’s a whole other blog.) The Paradine Case review is quoted in an advertisement for the film in Variety (15 January 1948), 3.

My outline of Passage to Marseille simplifies the plot architecture just a little. The first Devil’s Island block is actually two chunks, a brief one introducing a few of the team, followed by a return to the narrating situation on the ship, and then followed by much lengthier set of scenes on Devil’s Island. The logic of the “sandwich-structure” flashbacks remains intact, though.

Barbara Deming’sRunning Away from Myself: A Dream Portrait of America Drawn from the Films of the 40’s, pp. 23-25, fits the iconography and narrative reversals of Passage to Marseille into a wider trend of wartime patriots who, apparently having cast off their cynicism, make commitment to the cause seem a new form of their earlier despair.

The embedded-story strategy is a recursive one. How many levels can a viewer handle before confusion sets in? I raise the problem in discussing Inception here, and I mention Robin Dunbar’s suggestion that five layers is the limit most people can follow. The 1940s films I discuss in this entry have four, counting the framing situations, but Inception pushes the limit with its five.

An informative history of nested boxes, dolls, and the like across cultures can be found here, the source of my array of caskets in the illustration above.

The Locket.

P.S. 8 June: William Benzon, of the vivacious site The Valve and the blogsite New Savanna, has written to point out that what I’ve characterized as boxes-within-boxes belongs to a broader tradition known as ring composition. It is an ancient literary technique that can operate at many levels, from that of plot down to a passage of a few lines. The essential feature is that the components are arranged in that ABCDCBA pattern. Ring composition has been analyzed by Mary Douglas in Thinking in Circles, and Bill has written about it here. Thanks to Bill for reminding me!

Madison calling Budapest: Can you read me?

Can you look at this picture without smiling? I think it’s hard, for reasons that relate to one thread of the essay here. Thanks to Levi Buchhuber, age eight months, and Jim Cortada, grandpa.

DB here:

Next week several dozen bright, energetic researchers will be crowding into conference rooms at Elte University in Budapest for the annual meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. Full details on the event are here. As usual, I expect that a hell of a time will be had by all.

I’ve discussed the purposes and projects of the members of this dynamic bunch on earlier occasions. If you want a rundown, I’d suggest reading the items in chronological order:

*I sketch out the SCSMI project in this entry. There are more ruminations in two run-ups to the 2008 Madison SCSMI get-together (here and here), and one a year later summing up that event.

*For a report on the wonderful 2009 Copenhagen convention, go here.

*I try to sum up the wide-ranging 2010 Roanoke powwow here, while a recent blog, “Molly Wanted More,” can be considered an echo of that event.

*For an utterly fun introduction to some of the research on display at SCSMI, head to one of our most popular entries, the guest blog by Tim Smith called “Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD.”

This year’s paper line-up is especially enticing, and the prospect of seeing so many old friends is even more thrilling. Alas, for reasons beyond our control, Kristin and I aren’t able to attend. As the date draws near, my need to stay home saddens me more than I had expected it would. I must content myself with directing you, with all the fervor I can muster, to the event. Many of our members have told me that their first visit was life-changing, providing them a whole new social network that would encourage their research. Moreover, I notice that every year several participants tell me that they think this one was the best session yet. We’re just getting better, and we’re not going away! I should also alert you to the likelihood that many of the papers will be published in the SCSMI-affiliated journal Projections.

I thought, though, that I might participate a little at long range. So I’ve posted a web essay that sets out, in less technical terms, what my proposed paper for the convention would have tried to say. The essay, “Common Sense + Film Theory = Common-Sense Film Theory?,” reflects an effort to rethink ideas about filmic comprehension that I set out in Narration in the Fiction Film in 1985. This book was one of the first efforts to explore how findings in cognitive science might help us make progress in understanding cinematic storytelling.

I’d stand by much of what I argued there, but in the light of further thinking and later research (much of it conducted by SCSMI members), I wanted to float some ideas that recast and correct my arguments in the book. (Yes, I hope I’ve learned something in twenty-five years.) Some of my more recent notions are available in Poetics of Cinema and under the Film theory: Cognitivism category on this blogsite, but the conference provided a good occasion to submit to the sort of friendly but pointed critique at which my SCSMI colleagues excel.

Of course, give me another twenty-five years and I’ll probably find fault with what I say now. Others won’t need so much time.

Start with this question, which I think is one of the most fascinating we can ask:

What enables us to understand films?

Continue reading here.

To my SCSMI cohort: I wish you a superb gathering. See you next year, at Sarah Lawrence!

Joe Anderson, co-founder of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, opens the 2010 session at Roanoke.

Graphic content ahead

Kristin here:

Recently I received the June issue of Empire magazine. After the shock of realizing that, Ack! It really is almost June, I turned to the letters to the editor. I received an even worse shock when I read this one:

I recently discussed 2001: A Space Odyssey with my Film Studies teacher (I’m an A-level student), and mentioned (what the back of the DVD case says): “One of the most mind-blowing jump cuts ever conceived.” He told me the bone to satellite scene is actually a match cut. I then read issue 262 of Empire, and was very happy to see a Stanley Kubrick special. I noticed you also called it a “stunning jump cut”. After being told what a jump cut and what a match cut is and seeing a few examples (the jump cut at the start of Don’t Look Now, and then the match cut in 2001: A Space Odyssey), I am now confused as to why the DVD and Empire would call it a jump cut when it is a match cut.

Robby Burke, via email

It is a match cut. The offending writer has been put into a small room with only Eisenstein films for company. The moral of this story is always listen to your teachers, kids. And good luck to Owen Robinson on your Kubrick Film Studies unit. This is turning into hospital radio.

No wonder Mr. Burke is confused. His teacher and Empire both gave him answers that I would consider wrong, or at best imprecise to the point of vagueness. This rather surprised me. I enjoy reading Empire, which has somehow managed to keep itself fat and glossy when magazines like Entertainment Weekly have shrunk to the size of brochures. It even has occasional useful articles, like its retrospective section on Back to the Future in the April, 2010 issue. (As far as I can tell, this section has never made its way to the Empire website.)

The term “match cut” is, out of context, virtually meaningless. There are different kinds of match cuts, and not specifying which type one is referring to will leave Mr. Burke and the rest of us clueless as to what the teacher and the unnamed staff member for Empire mean.

Thinking I was missing something about the term “match cut,” I looked it up on Wikipedia and discovered that the teacher and the Empire staff member might have gotten their misinformation from the entry on that phrase. Its definition of a “match cut” is:

A match cut, also called a graphic match, is a cut in film editing between either two different objects, two different spaces, or two different compositions in which an object in the two shots graphically match, often helping to establish a strong continuity of action and linking the two shots metaphorically.

While the Empire use of “match cut” was only vague, this definition is simply inaccurate. The author goes on to say:

Match cuts form the basis for continuity editing, such as the ubiquitous use of match on action. Continuity editing smoothes over the inherent discontinuity of shot changes to establish a logical coherence between shots. Even within continuity editing, though, the match cut is a contrast both with cross-cutting between actions in two different locations that are occurring simultaneously, and with parallel editing, which draws parallels or contrasts between two different time-space locations.

I’ll agree that continuity editing is designed to smooth over the potentially disruptive quality of cuts. Matching anything within a scene is definitely different from cutting from an action in one place to a different action in a different place. But graphic matches are neither synonymous with “match cuts” nor the basis for continuity editing.

I also discovered that the “Further Reading” list at the bottom included two items, one of which was Film Art: An Introduction. One of those good news/bad news situations. The good news is, if you read the book, you will find out what graphic matches, and matches in general, really are. The bad news is, if you don’t, you might blame us for the contents of the Wikipedia entry.

A little detour into history

Most people don’t realize this, but David and I invented the term “graphic match.” As we recall, this happened in 1975. David was teaching a course that involved screening Yasujiro Ozu’s second color film, Ohayu (1959), a wonderful comedy about television, farting, and small talk. We had never seen the film before and were watching a 16mm print of it.

When the two shots below passed before our eyes, we both gasped and lunged for the projector. We ran the film back and watched the cut again. There was no doubt that Ozu had deliberately placed a bright red sweater in the upper left quadrant of the frame in one shot and a bright red lamp in the same basic position in the next shot. We didn’t know what to call this technique, so we dubbed it a “graphic match.” Two years later, when we started writing Film Art: An Introduction, we included the term as one technique of film editing and used Ozu’s match on red as one example. By now “graphic match” has been picked up to the point where we occasionally see it used in print.

If people, however, are tossing that term and “match cut” around so inaccurately–and even equating the two–then some definitions and examples seem in order.

Matcharama

“Match” as applied to editing simply means that some element is carried over from one shot to the next. That doesn’t necessarily mean that this element creates a sense of continuity.

In general, “continuity” means that a coherent space and time are continuing over the cut, so that the spectator’s understanding of a story isn’t disturbed by a sense that bits of time have been left out or that characters have changed positions at the cut. Most people watching a mainstream narrative film probably aren’t even aware of the editing, especially in conventional conversation scenes.

More specifically, “continuity” means a set of guidelines or loose “rules” that American filmmakers devised, mostly during the 1910s, to allow them to help create that clarity of narrative action in time and space. Within a scene, the most basic of these is the 180-degree rule or “axis of action,” the invisible line that runs through the scene perpendicular to the camera. If the camera stays on one side of that line, characters will stay in a consistent spatial relation to each other. Character A will be on the left in every shot, Character B on the right—unless one of them walks to a different part of the setting. In other words, the axis creates consistent screen direction.

The most basic kinds of matches are on appearance, position, action, and eyelines. Everyone knows that if a character is wearing a blue hat, showing her wearing a red one after the cut is a continuity error. Her appearance has not been matched. The same is true if she is resting her cheek on her hand in one shot, but has both hands flat on the table after the cut. If she is walking in one shot, she should not be running or standing still in the next. Even if the shots are made with a single camera and the actress repeats her actions, her position and movement should ideally be repeated so precisely that her action appears continuous. That’s a match on action, one of the most common continuity devices.

Smooth matches on action are difficult, especially if, as often happened in classic studio filmmaking, the two shots are made hours or even days apart. Even a supreme technician like Hitchcock can err. Here is a flagrantly mismatched passage from Suspicion. In the long shot, Johnnie (Cary Grant) reaches for the teapot with his left hand and starts to pour.

But then Hitchcock cuts in axially, the teapot is back where it was, and Johnnie once more reaches for it. By the time he’s pouring now, Lina has turned to watch him.

Editors traditionally like an overlap of 2-4 frames when they’re matching action on cuts, but this is a much longer overlap, something on the order of four seconds. Why we don’t usually notice such things is a source of considerable discussion in film circles.

The eyeline match is also very common. If a character looks at something offscreen, a cut shows us something in a different space, and we tend to assume that the character is looking at what we now see. Screen direction is important here, since if the character looks off right, when the next shot appears, we assume he is now offscreen left.

Not all continuity devices involve matches of these kinds. Crosscutting and flashbacks may move the action away from the space and even the time of a scene, but there are other cues that help us keep track of the ways in which these new spaces relate to the storyline.

None of this requires what we would consider a graphic match. Of course, if we see the same characters in the same setting from shot to shot, there will be an overall graphic consistency. They’re wearing the same costumes, and the background colors probably won’t shift greatly. But precisely because of that general consistency, we probably won’t notice the graphic qualities of the scene as being that important as elements of the editing. We’re busy following the story.

Graphic matches precise enough to be noticed as such tend to jolt us a little out of our smooth concentration on the story action. They are not the basic of continuity, as the Wikipedia definition claims. On the contrary, they often appear in films outside the continuity tradition. Abstract films often play on the graphic similarities (matches) or contrasts (mismatches) among shapes from shot to shot. Such abstract play is, in effect, their subject, and we pay attention to the pictorial flow as we would pay attention to story in a conventional narrative film.

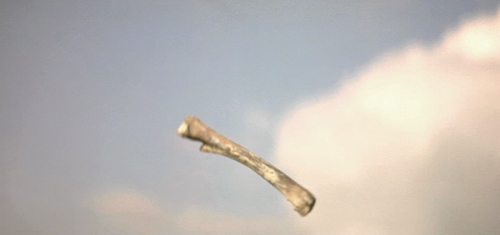

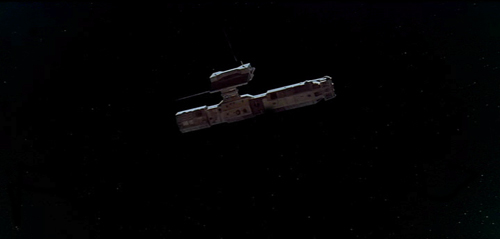

When close graphic matches or jolting graphic contrasts appear in narrative films, they may or may not play a narrative role. The famous bone/spaceship cut in 2001 is a graphic match. It’s not a match on action, since two different objects in completely different times and places are shown. It’s not a jump cut for the same reasons.

Here the graphic match is not really very close. The sky is bright and blue behind the bone, while it is dark behind the spaceship. Similarly, the bone is light in color, while the spaceship is initially dark, though it does brighten slightly as it moves. The only graphic element matched is the general shape and motion of the two objects.

The function, I assume, is to jolt the audience with the dramatic transition across millions of years and from earth into space. Thus here the graphic match has a narrative function, though it does not create the smooth movement from one scene to another that classical films tend to have. It’s more like what is sometimes called a “shock cut,” one which startles the viewer. The cut to the screeching cockatoo in Citizen Kane is one of the most famous examples, though it primarily involves sound and a strong graphic contrast.

A transition somewhat similar to the one in 2001 occurs early in Aliens, an example which we use in recent editions of Film Art. A dissolve moves from a close-up of Ripley’s sleeping face to a view of part of the earth seen from space. Again there is a passage through time and space, though the interval is presumably only a few months. Here the graphic match is much closer than in the 2001 transition, with the colors as well as the shapes being kept fairly consistent. This graphic similarity and the dissolve that emphasizes it ease us from one scene to another rather than jolting and surprising us.

In the hands of an experimental filmmaker or of an unconventional director like Ozu, who avoids obeying Hollywood’s continuity guidelines, graphic matches don’t necessarily play a narrative role. They are included as an extra layer of engagement for the viewer. We don’t, or at least shouldn’t, expect to be able to interpret them. I would contend that the link between the red sweater and the red lampshade is there for pure pleasure. You can come up with an interpretation of the graphic match if you try hard enough—but if you do, please don’t tell me about it. I suspect it would interfere with my enjoyment of that scene when I next watch Ohayu.

I don’t think the cut serves even so modest a function as establishing space at the beginning of a scene. Here’s the shot that actually begins the scene and leads to the sweater and lampshade shots:

And here’s the one that follows the lampshade shot:

The woman is a minor character. She and her husband live in the suburban housing complex where the much of the action is set. They are more modern in their habits than their neighbors, wearing western clothes rather than kimonos and owning the only TV in the complex. They function primarily to introduce the two young boys in the central family of the story to TV, since they hospitably let the local kids visit them to watch it. The scene following the graphic match shows the wife packing to move. Their absence will precipitate a crisis when the boys demand that their parents buy them a television. The strife among the family members forms the basis for much of the rest of the action.

So the packing scene is important. Yet Ozu uses two shots that he wouldn’t need, thus delaying the scene’s beginning. The extreme long shot of the housing complex doesn’t tell us which house will form the setting for the upcoming scene. The red sweater is in the distance, but barely visible. We certainly wouldn’t notice it or get any clues about the narrative from it. Yet Ozu cuts to a closer view of the sweater and a towel. The houses in the background are all identical, and we don’t know which one belongs to which characters or which we will enter in the next shot.

The first interior view would be a logical establishing shot for the scene. The modern furnishings and especially the television box let us know where we are, and the boxes might hint that the inhabitants are packing to leave. So we are not surprised when we see the modern wife in the subsequent shot. But Ozu puts in the other two as part of his typical series of transitional shots that show the spaces between locales where action occurs.

The graphic match, I would suggest, is simply part of Ozu’s distinctive style. It’s playful and fits in with the general graphic beauty of his films, which includes bright splashes of color, careful compositions using the lines of the sets, and precise placements of props.

Returning to the Wikipedia entry for “match cut,” there is a section that mentions several examples, including the one that inspired Mr. Burke’s letter:

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey contains a famous example of a match cut. After an ape discovers the use of bones as a tool and a weapon, there is a match cut to a spacecraft or satellite in orbit. The match cut helps draw a connection between the two objects as exemplars of primitive and advanced tools respectively.

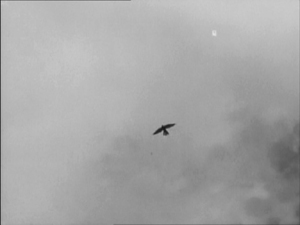

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale contains the influence for the 2001: A Space Odyssey match cut in which a fourteenth century falcon cuts to a World War II aeroplane. The sense of time passing but nothing changing is emphasised by having the same actor, in different costumes, looking at both the falcon and the aeroplane.

An early example comes from Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane which opens with a series of match dissolves that keeps the lit window of C.F. Kane’s in the same part of the frame while the cuts take us around his dilapidated Xanadu estate, before a final match dissolve takes us from the outside to the inside where Kane is about to die.

Another match cut comes from Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962) where an edit cuts together Lawrence blowing out a lit match with the desert sun rising from the horizon. Director David Lean credits inspiration for the edit to the experimental French New Wave. The edit was later praised by Steven Spielberg as inspiration for his own work.

How the author knows that A Canterbury Tale (see below) influenced 2001 is not clear. The site footnoted (here) simply says that the cut (below) “anticipated” Kubrick’s scene in 2001. The film was released in the U.S. in early 1949, so possibly Kubrick saw it and remembered the scene nearly twenty years later. By the way, Powell and Pressburger create a double graphic echo, roughly matching the two similar dark objects against a light sky and making the two shots of the men looking upward strongly resemble each other as well.

The Citizen Kane opening, with its precise placements of the one lit window from shot to shot, is a good example of graphic matches. I am not going to touch the question of what a “match dissolve” is.

The cut from the match to the Jordanian desert horizon in Lawrence of Arabia is a trickier case. The match is placed in the left half of the anamorphic widescreen frame, while the sun rises in the right half. Moreover, the match shot is very bright, while the desert scene is fairly dark, with the sun only beginning to glow above the horizon a short way into the shot. Graphically there is not much to link them, though I think the spectator does get a strong sense of a connection between the match and sun. I’d say it’s a conceptual link, not a graphic one. It’s a link that we make on the basis of two bright objects that are not compositionally or spatially matched but simply juxtaposed.

Mr. Burke, your inquiry was perfectly reasonable, and I hope I have helped clear up your confusion.

We supply two flagrant examples of mismatched action, figure placement, and setting in Bringing Up Baby in this blog entry. Interestingly, probably no one but a professional notices them, because the relative positions of the major figures are consistent, as are the overall compositions of the shots. But then, as Dan Levin points out, we are not that sensitive to continuity disruptions in the real world either!

A Canterbury Tale.