Hitchcock again: 3.9 steps to s-u-s-p-e-n-s-e

Thursday | December 5, 2013 open printable version

open printable version

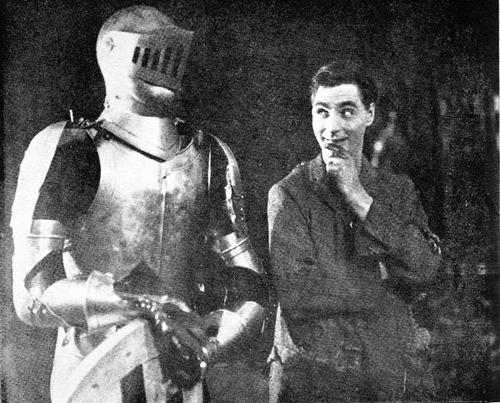

Henry Edwards; Alfred Hitchcock.

DB here:

My previous entry reminded you that Hitchcock was notorious for distinguishing between suspense and surprise. To achieve suspense, he maintained, the audience has to be aware of more than the characters know. Surprise arises when we know as much as the characters, or less. Hitchcock also declared his general preference for suspense, since it provides prolonged tension while surprise produces merely a momentary buzz. The mystery was: Where do this distinction and this preference come from? Are they original with Sir Alfred, or can we find precedents?

The story so far:

Step 1: The distinction itself goes back at least to the eighteenth century and the playwright/theorist Gotthold Ephriam Lessing. Lessing likewise expressed his preference for suspense because it demanded superior craftsmanship and yielded stronger effects on the audience.

Step 2: The distinction and the preference for suspense was still circulating in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century commentaries on theatre. My entry also mentioned a 1922 screen playwriting manual by Howard Dimick that took the same stance.

So we’ve located general conditions for influence. By the early 1920s, the suspense/surprise doublet was still circulating in the worlds of film and theatre, when Hitchcock was starting his career. But influence, like its source-word influenza, requires close contact. It would be good to find the secret agent who might have passed along the idea to the young director.

Step 3: My P.S. to the entry ropes in one candidate: Eliot Stannard. Richard Allen proposed him as a possibility, and Ian Macdonald supplied information that strengthened the suspicion. Stannard was a busy screenwriter of the period, who worked closely with Hitchcock on nearly all his silent pictures, and he even wrote a manual on screenwriting. Although he apparently didn’t talk about suspense and surprise in print, he would have known William Archer and other drama theorists who did. Stannard could well have initiated Hitchcock into the idea.

Step 3.9: But do we have the wrong man? After I posted my P. S., another foreign correspondent weighed in. Charles Barr writes:

A key figure here is Henry Edwards. Director in British cinema 1916-1937, and actor for much longer. His (lost) feature film Lily of the Alley in 1923 made a big point of avoiding intertitles. Whether or not he saw it, Hitchcock must have at least been aware of it, even though later he always said that The Last Laugh was the first such film. And already in 1920 Edwards had spelled out the surprise/suspense distinction: see attachment from the trade paper The Bioscope.

Edwards was indeed a major figure, as producer, actor, and director during the 1910s and 1920s. At the British Film Institute site, Geoff Brown and Briony Dixon provide a lively account of his career. He was clearly in a position to influence younger filmmakers.

The 1920 Bioscope article, cited in the Brown/Dixon overview and supplied to Charles by Ph.D. student Michaela Mikalauski, is a revelation. Edwards writes:

We must so construct our story that suspense is created–suspense is the dread that something may happen, and it is on this that we must build our story.

We must so construct it, that by careful preparation impeding difficulties or dangers are looming up before our characters. We must show the audience these dangers, and keep our characters ignorant of them until the proper moment; and it is the nearing of the danger to the blissfully ignorant character, making us long to cry out and warn him, that give suspense.

Tellingly, Edwards uses an example of an explosion. Imagine that our hero, wandering in the wilderness, has taken shelter in a shack. He sits on a box and lights a cigarette. While he has a leisurely smoke, his match has ignited some dry rubbish by the box. He rises and leaves the shed, just as the box is blown to pieces. Now we realize that it contained dynamite.

Here is a case in which there is expectancy, and never for a moment suspense, because the audience does not know of the impending danger to the character.

Now let us defy the critics who clamour for “surprise” in film construction, and tell the incident in the language of the screen.

Edwards goes on to imagine that we’ve seen quarrymen leave the box of dynamite behind. When the hero ambles in and settles down on the box for a smoke, we’re already apprehensive. Now every gesture he makes prolongs the tension, and we watch anxiously as the discarded match ignites scraps beside the box.

It becomes a question as to which will take the longer, the hero to recover his strength and go, or the box of dynamite to explode. Here is sheer suspense, and when there hero has gone it is no jar to the audience but rather a pleasurable expectancy to see the box explode harmlessly in the air.

After supplying another, more psychological example, Edwards concludes his piece: “The letters of the film alphabet are s-u-s-p-e-n-s-e.”

This article–published the very year that a young and innocent Hitchcock began work for Famous Players-Lasky in Islington–shows that the terms in which Hitchcock understood the suspense/ surprise distinction were already clearly articulated in English film culture. Even the bomb situation that Hitchcock would summon up for Truffaut is there in Edwards’ piece. But of course this information doesn’t sabotage the standing of Stannard, who may have read the Bioscope article and transmitted its lesson to Hitchcock in later years.

I confess I had thought I was done with the thing, but the last few days have brought a small frenzy of emails, and I’m feeling a bit of vertigo. Still, there seems not a shadow of a doubt that Hitchcock was maintaining his faith in a storytelling device that goes back quite far and still had a grip on the formative years of British and American cinema.

Thanks very much to Charles Barr for the information and for sending me the Edwards article. It was published as “The Language of Action,” Bioscope (1 July 1920), supplement p. iv. Thanks also to Michaela Mikalauski for locating the piece, and to Antti Alanen for forwarding some crucial email addresses.

Charles’ revised edition of his Vertigo monograph includes some further comments on the suspense/surprise distinction as it relates to that film. Charles is also completing a new book, with Alain Kerzoncuf, called Hitchcock: Lost and Found. It surveys the little-known films from all periods of Hitchcock’s career. “It devotes some 15,000 words to ‘Before the Pleasure Garden,’ discussing the 21 films Hitchcock was involved with (surviving in whole or part or not at all) and also a bit on the wider context, which is where Edwards comes in. This is all about to go to the publisher (Kentucky) and if all goes well will be out by the end of 2014.”

I’m grateful to all. The little adventure, which I suspect is not quite over, has been rich and strange.

Broken Threads (1918), produced and directed by Henry Edwards, who also starred.