Zip, zero, Zeitgeist

Sunday | August 24, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014).

DB here:

The silly season always seems to catch me off guard. This time I got the word in a New York Times feature, “The Moviegoers.”

Here two writers, Frank Bruni and Ross Douthat, conduct an email conversation about recent films. You may have thought that the Times already has a large stable of movie reviewers, headlined by Manohla Dargis and A. O. Scott. But mainstream movies are very accessible (as opposed to, say, serial music or Baroque architecture), so nearly everybody has something to say. And because nobody knows what counts as expertise in movie reviewing, why not bring on two of the commentariat? Once you become a public intellectual, what you say about anything is interesting.

Granted, both participants in the dialogue, Frank Bruni and Ross Douthat, have been movie reviewers. Mr. Bruni wrote for the Detroit Free Press, and Mr. Douthat currently covers film for the National Review. Through some process yet unexplained, these movie reviewers became second-string social and political pundits for the Times. That would seem a step up, so why put them back in the reviewing game?

The rationale is supplied in the series introduction, which talks of the plan to discuss “movies, pop culture, television, and other real-world distractions.” The Times style guardian might want to pause on the last phrase: Are these phenomena distractions in the real world (as in “real-world opportunities”)? Or are they distractions from the real world? I think the writer means the latter, which translates into this: Politics is the important stuff, mass art is a lightweight diversion. And we all need diversion, especially a newspaper aiming to attract readers under fifty.

So we have two Op-Ed columnists taking a break from serious matters in order to shoot the breeze about summer releases. In “Two Thumbs Up…Yer Arse.” Charlie Pierce, our fouler-mouthed Mencken, has exposed some curious assumptions about poverty displayed in the Moviegoers’ first round of chitchat. What interests me here is another aspect of the column, which showcases one standard move that many reviewers make.

The problem for serious people like Mr. Douthat and Mr. Bruni is this. If movies are “real-world distractions,” why spend any time talking about them? More specifically, why should political pundits talk about them? The obvious answer: Somehow these products of popular culture open a window into what’s really going on. Mr. Douthat:

In this sense I do think moviemakers are tapping into the American psyche, but I also think they’re replicating a flaw of the American political debate. I’m not sure we’ll get very far by painting the rich as morally hopeless people who must be subverted, vanquished, overtaken.

And when Mr. Bruni asks, “Tell me about the trend that made you happy, and (speaking of political allegories) whether you like ‘Apes’ as much as everyone else,” Mr. Douthat replies:

There was something poignant about watching “Apes” against the backdrop of the mess in the Middle East and of the war in Israel and Gaza, because it’s a disturbingly good allegory of reciprocal mistrust, asking the right questions about how peace ever reigns when combatants can’t bring themselves to forgive error, to take the first step, to turn from the past and focus on the future, to start afresh. It’s a disturbingly good allegory about corrupt leaders, too: how they whip up fervor in the service of their own ambition; how we rise and fall based on the clarity and wisdom with which we choose them.

You may want to reply that if this is what the Times wants, you will undertake to supply them with 3000 words of it every day at reasonable rates. But put aside the banalities about politics. I’m interested in the suggestion that movies can bear traces of the national psyche, or reflect national debates we’re having right now, or provide inadvertent “allegories” of contemporary history.

These ideas enjoy an astonishing popularity. They are staples of movie journalism. The trouble is that they don’t hold up.

Reflections on reflectionism

That mass entertainment somehow reflects its society is, I believe, the One Big Idea that every intellectual has about popular culture. The notion shapes the Sunday Times think piece about how the movies of the last few months capture the current Zeitgeist (or one a while back). It informs the belief that we can define periods in American popular art by presidential eras–Leave It to Beaver as cozy Eisenhower suburban fantasy, Forrest Gump as an expression of Clinton-era post-Cold-War isolationism. Reflectionism may be the last refuge of journalists writing to deadline, but it’s also found in the industry’s talk about itself. “Oscar Best Pic Contenders Reflect America’s Anxieties,” Variety announced last winter.

The threat of circularity. Behind this Big Idea is an assumption that cinema, being a “popular art,” tends to embody some state of mind common to the millions of people living in a society. The very idea of a massive mind-meld like this seems implausible. America’s anxieties and our national psyche? The anxieties of the 1% are not yours and mine, and I doubt that even you and I share a psyche.

The argument easily becomes circular. All popular films reflect society’s attitudes. How do we know what the attitudes are? Just look at the films! We need independent and pretty broadly based evidence to show that the attitudes exist, are very widespread, and have been incorporated in films. And it won’t do to simply point to the same attitudes surfacing in TV, pop songs, mass-market fiction as well, because that just postpones the problem of correlating the attitudes with groups of living and breathing people.

Critics seem to assume that if a film is successful at the box office, it must reflect the audience’s inner life. Yet the sheer fact of a movie’s popularity doesn’t prove that these attitudes are out there. Just because Spider-Man (2002) was a huge success doesn’t mean that it offers us access to America’s national mood or hidden anxieties. People spend time with a piece of mass art for many reasons: to kill an idle hour, to meet with friends, to find out what all the fuss is about. After the encounter, consumers often dislike the art work to some degree, or they remain indifferent to it. Since people must buy the movie ticket before they experience the movie, there can’t be a simple correlation between mass sales and mass mood. You and lots of others may be suckered into going to a film you dislike, but just by going you’ve already been counted as among those who support it. Doubtless many people enjoyed Spider-Man. But it’s very difficult to say how many.

And did all of the patrons who enjoyed it do so for the same reasons? That remains to be shown, and it’s hard. We know that a movie may appeal to several audiences at once, packaging a range of appeals. In fact, it’s a strategy of the film industry to produce movies that contain fuzzy messages, contrary attitudes, and something for nearly everybody. Must we find reflections of cultural needs in every aspect of a movie that might appeal to somebody?

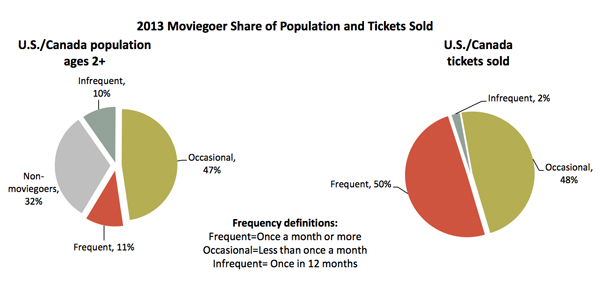

Movies are narrowcasting. The film audience is a skewed sampling of the population. According to industry statistics, about one-third of Americans over the age of two never go to the movies, and another ten percent go once a year.

Another 40% go “occasionally”–less than once a month. It turns out that the heavy moviegoers, those going once a month or more, are currently just 11% of the population. Take Dawn of Planet of the Apes. Assuming an average ticket price of $8 and no repeat viewings, at most about 25.5 million Americans and Canadians have seen the movie. That’s about 7% of the countries’ total population. We would need to tell a pretty full story about how the mental life of 350 or so million people gets into movies seen by a thin, self-selected slice of the population.

Moviegoers are atypical of the population in other respects. Since the beginning, Hollywood cinema has catered to the middle class. Moviegoers have been younger, better educated, and better-off economically than non-moviegoers.

The real mass medium of our time is network television (as radio was before). On one night, a single episode of The Big Bang Theory can attract 19 million viewers. A film that had that viewership across an opening weekend would take in over $150 million. That is $50 million more than the latest Transformers movie garnered at its debut. If Messrs. Douthat and Bruni want to take the national temperature, they should watch TV–ideally, the ads on the Super Bowl (shown to 112 million viewers).

Actually, you can argue that television really is a more reliable barometer of mass tastes, not just because of its prevalence but because TV viewing depends on recidivism. People may not know they’ll like a movie before they attend, but they tune in to shows that have proven to satisfy them. Still and all, mass taste is not the national psyche.

The long road from the White House. A primary prop for reflectionists is politics. Talk about an American film of the 1950s and sooner or later someone will invoke the reign of blandness that was (purportedly) the Eisenhower administration. But why do we assume that the population’s mind set switches its course whenever a new President is elected? Many voters stubbornly adhere to the same values election after election; others vote in order to throw out a rascal and aren’t at all satisfied with the newcomer.

There couldn’t be a direct tie between elections and moviegoers’ attitudes. About thirty percent of today’s audience consists of people too young to vote. The most reliable voter turnout is among the over-forty-five set, which until recently constituted only about twenty percent of moviegoers. Of course, maybe movies reflect the attitudes of non-voters, or people who are indifferent to politics. But then why identify periods of political history with periods of movie history?

Reflectionists have always been reluctant to offer a concrete causal account of how widely-held attitudes or anxieties within an audience could find their way into art works. What precise story could we tell to explain how changing the occupant of the White House can affect popular culture? How exactly does a party platform or a candidate’s charisma or the new administration’s policies seep into Hollywood movies for the multitudes?

Movies’ crystal ball. If there ever were a dominant mood at large in the land, it would be very difficult for that mood to find its way into a current movie. There’s often a lag of several years before a script gets to the screen. Many of the films released in 1997, though read as responding to current crises, were bought as projects in 1993 and 1994. Dawn of Planet of the Apes was begun in 2011, written through 2011-2012, and began shooting in April of 2013–all before the current standoff between Israel and Hamas.

Maybe the moviemakers are somehow in touch with political forces before they crystallize? One critic has proposed that films can have this prophetic power. Puzzled that no Obama-era movies had emerged by 2012, J. Hoberman suggests that the most “Obama-ite” ones came out before Obama was elected:

The longing for Obama (or an Obama) can be found in two prescient 2008 movies—WALL-E (the world saved by an endearing little dingbot, community organizer for an extinct community) and Milk (portrait of another creative community organizer—not to mention a precedent-shattering politician who, it’s very often reiterated, presented himself as a Messenger of Hope).

This is nearly a miracle. Somehow these filmmakers sensed that Americans (well, 53% of the people voting) were yearning to be led by a community organizer. But how specifically could the filmmakers have arrived at that prescience? In fact, they would have had to be long-range prophets. Milk began as a 1992 project, and the final version of the script was prepared in 2007. The Pixar adepts started talking about WALL-E in 1994 and began drafting scripts in 2002. Why don’t we ask filmmakers to predict our next president right now?

Pick and choose. Of all the films of the summer, Bruni and Douthat settle on a few. Of all the hundreds of 2008 films, two presage Obama. This selectivity is typical of the reflectionist approach, which typically ignores the range of incompatible material on offer.

If 1940s film noir reflects some angst in the American psyche, how to explain the audience’s embrace of sunny MGM musicals and lightweight comedies in the same years? The year 1956 saw the release of The Ten Commandments, Around the World in 80 Days, Giant, The King and I, Guys and Dolls, Picnic, War and Peace, Moby Dick, The Searchers, and The Lieutenant Wore Skirts. Pick one, find some thematic concerns there that resonate with social life of the time, and you have a case for any state you wish to ascribe to the collective psyche. But take any other movie, or indeed the industry’s entire output, and you have a problem. One alternative is for us to find that the films share common themes, but these are likely to be of an insipid generality. Or we could float the rather uncompelling claim that several hundred films reflect hundreds of different, and contradictory, facets of the audience’s inner life.

Consider the source. Of course filmmakers sometimes deliberately include political comment. But then the film is “reflecting” the purposes of its particular makers, not the mass public. The filmmaker may claim to be tapping the Zeitgeist, but it’s really the Zeitgeist as she or he understands it. It’s not the public expressing itself spontaneously and unselfconsiously through the movie.

Movies use a lot of collaborators, and they may have varying agendas. The most powerful players are inevitably going to shape the initial project in specific, often personal ways. The preoccupations of the screenwriter, the producer, the director, and the stars necessarily transform the given idea. And these workers, living hermetic lives in Beverly Hills and jetting off to Majorca, are far from typical. How can the fears and yearnings of the masses be adequately “reflected” once these elites have finished with the product? Maybe some violence in American films gets there not because the crowd secretly wants it but because Hollywood creators compete in pushing the envelope. Once more we need a story about how widespread opinions get incarnated in the work of an unrepresentative group.

In sum, reflectionist criticism throws out loose and intuitive connections between film and society without offering concrete explanations that can be argued explicitly. It relies on spurious and far-fetched correlations between films and social or political events. It neglects damaging counterexamples. It assumes that popular culture is the audience talking to itself, without interference or distortion from the makers and the social institutions they inhabit. And the causal forces invoked–a spirit of the time, a national mood, collective anxieties–may exist only as abstractions that the commentator, pressed to fill column inches, invokes in the manner of calling spirits from the deep.

Primate see, primate do

This isn’t to say that society has no impact on films. Of course it does. But we understand that process best by taking film as film.

Film critics serve us best when they explore how a film uses the medium to yield its effects. Critics can enlighten us about how filmmakers work with their givens (subjects, themes, genres, artistic traditions, star personas) and generate an experience shot through with meanings, feelings, and ideas. We should recognize that a large part of any movie is the result of will and skill, not the passive reflection of vague social turmoil. There will be some unintended effects too, of course, but we can try to understand those as coming from specific conditions of production practices, traditions, and creative options.

One first step, for example, would be to consider Dawn of the Planet of the Apes as following the plot pattern of the revisionist Western.(Spoilers follow.) The humans, like settlers in the west, need resources held by the apes, who live in self-sufficient harmony with nature. They wish others no harm. A well-meaning emissary from the humans, Malcolm, leads a team into ape territory to tap an energy source. Thanks to Malcolm’s promises of peaceful coexistence, humans and apes become friendly. But other members of Malcolm’s team don’t trust the apes and provoke violence. There is also the brooding ape Koba, who wants revenge for his mistreatment in experiments. The peace treaty is broken by both sides.

Koba, Caesar’s friend and rival, escalates the war with the humans when he discovers the cache of weapons. While Caesar tries to keep Koba from fomenting rebellion, Malcolm must try to restrain the humans’ leader, Dreyfuss. This is a familiar duality: the unruly tribal brave hot for vengeance who must be disciplined by the wise chief, and the sensible lieutenant who tries to restrain his rapacious superior.

The science-fiction premise has been shaped to fit the familiar pattern of liberal Westerns, in which blame can be placed on weak, cowardly, vengeful, or power-hungry individuals who block well-meaning leaders from finding peace. The classic equivocation of Hollywood film (there’s always an element that says, “Yes, but then there’s…”) is well summed up by the ambivalent to-camera glare of Caesar that begins and ends the movie: Angry? Sorrowful? Defiant? Implacable? Your mileage may vary.

The political themes are sculpted in another way, through family parallels. Caesar has a wife, Cornelia, and a son, Blue Eyes. Malcolm has a wife, Ellie, and a son, Alexander. The prospect of peaceful coexistence between human and ape is encapsulated in the two families’ growing fondness for each other. The parallels are sharpened by contrasts. Alexander comes to accept the apes, while his more rebellious adolescent counterpart Blue Eyes temporarily aligns himself with the false father Koba—only to prove himself loyal to Caesar at the climax.

By contrast, Dreyfus and Koba are lone males, without women or offspring. Granted, we are allowed some sympathy for both: Koba has been mistreated by humans, and Dreyfus has lost his family in the collapse of civilization. Still, Caesar is morally superior to both because he has lived in each world harmoniously. Before the final battle, the wounded Caesar gets to recall his first human family, typified by his father figure, on video.

Onto the settlers vs. Indians plot, then, is grafted what film scholars have called a “family adventure” pattern, one that became prominent in the 1980s and 1990s with E. T.: The Extraterrestrial, Jurassic Park and other films seeking “four-quadrant” success. The result is more made-in-Hollywood archetype than grassroots allegory.

My sketch is Film Studies 101 and needs plenty of nuancing. To go further we should consider how this movie, or any movie, puts flesh on its plot bones. How does the film handle point-of-view and exposition? How does it generate sympathy or antipathy? How does it create character conflicts both external and internal? Does it accord with the sharply contoured plot architecture characteristic of US studio filmmaking (and maybe popular literature too)? If I were trying to do a finer-grained analysis of Dawn, I’d try to understand how the Western and family-adventure templates intertwine with these factors and gain force as the film unfolds.

The point would be not to suggest that these plot patterns reflect the attitudes or anxieties of the audience, let alone a national psyche. Rather, the patterns are chosen by the filmmakers because they have proven emotionally appealing to at least some viewers (and apparently in cultures outside the US). And they can be fashioned to accord with contemporary norms of moviemaking. Instead of passive reflection, we have active creation.

It isn’t all controlled by the filmmakers. Like all actions, filmmaking can have unintended consequences. If some members of the audience respond in the way the filmmakers wanted, so far, so good. If the results are grasped in ways that the makers didn’t expect or prefer, that comes with the territory too. Mass-market filmmakers take inherited forms and tweak them in new ways. The audience, in its turn, appropriates what it’s given, sometimes in predictable ways, sometimes in unpredictable ones. No national psyche is needed for this process to keep rolling.

Instead of reflection, better to think of refraction, the bending and reconfiguring of social themes under the pressure of filmmaking traditions. We understand mass-market films better when we see them as, sometimes opportunistically, grabbing material from the wider culture (whether that material reflects mass sentiment or not) and transforming it through narrative and stylistic conventions. That transformation, or rather transmutation, is central to the artistry of popular entertainment.

Movies are worth studying for themselves, not just as channels for Op-Ed memes. Critics who are sensitive to the art, craft, history, and business of cinema will be able to enlighten us about all aspects of a film, including its political ones.

Jeff Smith’s new book, Film Criticism, The Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds examines how critics of the 1950s found allegories of resistance to HUAC in movies made at the time. It’s a good reminder that this sort of reflectionist criticism goes back pretty far.

In tune with Jeff’s argument, in an earlier entry I argued that reflectionist readings of popular cinema intensified during the 1940s. But our best critics pushed back. Parker Tyler proposed that movies don’t so much reflect social myths as they invent their own, and he suggested that the process follows the zany logic of dreams. Otis Ferguson, James Agee, and Manny Farber mostly avoided Zeitgeist explanations and talked about films’ implications in relationship to art, craft, and other media and artforms. I survey their work in a series of recent entries: on Ferguson, on Agee, on Farber (here and here), on Tyler, and on their originality, their cultural context, and their legacy.

The pie chart come from the MPAA report on 2013 moviegoing, p. 11.

For a wide-ranging and skeptical examination of one aspect of this topic, there’s Alan Hunt’s article, “Anxiety and social explanation: Some anxieties about anxiety,” Journal of Social History 32, 3 (Spring 1999), 509-528.

Peter Krämer developed the concept of the family adventure film in contemporary Hollywood. See his “Would You Take Your Child to See This Film? The Cultural and Social Work of the Family Adventure Movie,” in Steve Neale, ed. Contemporary Hollywood Cinema (Routlege, 1998), 294-311.

If there’s an allegory in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, perhaps it’s a Bolshevik one. Josef Stalin was known as Koba, which would make Caesar a Lenin figure and Rocket a stand-in for Trotsky. (I doubt that the conservative Mr. Douthat would welcome this reading.) If the reference is intentional, it provides a good example of how a Hollywood film simply seizes cultural flotsam willy-nilly, perhaps to give intellectuals something to ponder. As Christopher Nolan explains of his Batman trilogy: “We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks.”

Parts of today’s sermonette are pulled from an essay published in Poetics of Cinema in 2008. That essay also charts areas of control that filmmakers and audiences enjoy. Another entry on this site dealt with these questions in relation to The Dark Knight and, again, the good, grey Times.

Daumier: Types Parisiens (1840-1843): “Ah, I can see my street, there’s my house, there’s my garden and my wife, I can see Laurent – Oh, I have seen too much.”