An auteur, three archives, and the archivist as auteur

Wednesday | September 17, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

City of Sadness (1989).

DB here:

The books have been piling up again, and so I pass along some recommendations. This time the volumes are unusually handsome. Apart from what they say, these publications display how sumptuous a serious film book can be.

Particularly welcome, in light of the touring retrospective of Hou Hsiao-hsien films that began at MoMI on 12 September, is Richard I. Suchenski’s anthology of writings on and by the director. Hou Hsiao-hsien is packed with color illustrations and fully up to the standard of other publications from the Austrian Filmmuseum.

Particularly welcome, in light of the touring retrospective of Hou Hsiao-hsien films that began at MoMI on 12 September, is Richard I. Suchenski’s anthology of writings on and by the director. Hou Hsiao-hsien is packed with color illustrations and fully up to the standard of other publications from the Austrian Filmmuseum.

Some of our top critics and scholars have contributed essays. From Japan comes Hasumi Shigehiko on Flowers of Shanghai; from France, Jean-Michel Frodon on Hou’s collaboration with Chu Tien-wen; from Canada, James Quandt, eloquent as ever on Three Times. American scholars are here too. We have Jean Ma on The Puppetmaster, Abe Mark Nornes on calligraphy and frame space, Kent Jones on time in Hou, and James Udden on Dust in the Wind. Jim is author of the first English-language book on Hou and a contributor to this website. To these essays are added the unique perspectives offered by Taiwanese observers Peggy Chiao on City of Sadness and Wen Tien-hsiang on unmarried women in Hou. A wide-ranging introduction by Richard brings out virtually all the artistic, political, and cultural issues that have been raised by Hou’s body of work.

Unabashedly auteurist—and what’s wrong with that?—the collection adds even more value by including an interview with Hou and Chu, who supply precious information about the work-in-progress The Assassin. There are also statements by three distinguished directors: Olivier Assayas, Jia Zhang-ke, and Koreeda Hirokazu. Koreeda notes: “Life’s details (like eating) should be respected.”

We learn as well about the craft behind the artistry. We get a cascade of information from artistic collaborators, including cinematographers, sound designers, actors and others. For example, Tu Duu-chih, sound expert, says: “What [Hou] wants is a natural form of expression and he always manages the atmosphere to meet his needs. If he shoots a drinking scene, for example, he will select real dishes and alcohol and they must be delicious.” Delicious is a good word for this book too, an absolute necessity for every serious cinephile.

Birthday greetings to Vienna and Brussels

Speaking of the Austrian Filmmuseum, it celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this year. To celebrate, it has issued a heavyweight, unorthodox boxed set, The Austrian Film Museum at Fifty. Director Alexander Horwath has done a monumental job in bringing a great deal of material together, creating not only a history of the Filmmuseum but a real contribution to international film culture.

In volume one, Aufbrechen (Setting Out), Eszter Kondor provides a history of the institution, with emphasis on its emergence the 1960s and 1970s. Volume two pays homage to Béla Balázs with the title Das sichbare Kino (The Visible Cinema). This is a plump anthology of texts, pictures, and documents from the museum’s history. Given the fact that Peter Kubelka was curator for many years, you’re not surprised to find a letter from Michael Snow and an email from Ken Jacobs. But I didn’t expect an interview with Groucho Marx (letter appended) and correspondence from Don Siegel. This volume also includes a complete record of programs at the museum.

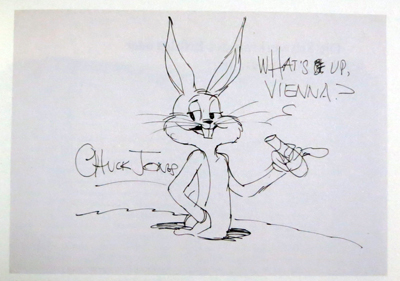

Volume three, Kollection, is a visual treat. It gives us a short history of film in fifty items. The survey includes The Unfinished Letter, a 22mm Edison film ca. 1911-1913, outtakes from Murnau’s Tabu, Morgan Fisher’s site-specific Screening Room (1968), Kurt Kren’s leather jacket, Chuck Jones’ What’s Up, Vienna? (1983), and frames from Norbert Pfaffenbichler’s dizzying Notes on Film 03: Mosaik Mécanique (2007).

The texts in all of the books are in German, but there are so many posters, photos, sketches, diagrams, and storyboards (one by Vertov) that you learn merely by browsing. These volumes are a must for research libraries with a focus on film.

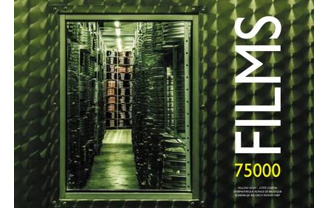

No less idiosyncratic is another anniversary volume, this one from the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, now known as the Cinematek. It was founded seventy-five years ago and, as if by cosmic convergence, it holds 75,000 film titles. But the book, 75000 Films, isn’t a celebration of this particular museum. It’s a book about film archiving in general. As curator Nicola Mazzanti puts it in his introduction:

No less idiosyncratic is another anniversary volume, this one from the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, now known as the Cinematek. It was founded seventy-five years ago and, as if by cosmic convergence, it holds 75,000 film titles. But the book, 75000 Films, isn’t a celebration of this particular museum. It’s a book about film archiving in general. As curator Nicola Mazzanti puts it in his introduction:

Film archiving is already changing and in a few years will be very different from what it is now. New skills, new machines, new people. As no book like this one exists about film archiving we wanted to make sure that at least one is published before the picture changes completely.

What will change? Chiefly, the sheer tactility of the work.

Inspecting a film to check its conditions and its history is all about a physical relation with the material. While winding through a reel of film your fingers run along the edges to feel imperfections and damages. One bends a piece of film to assess its brittleness, caresses a splice to check its resistance. . . .

In other words, it is a precise, careful, dedicated and highly specialized work that often is as tedious as rewinding hundreds and thousand of reels (by hand, as electric motors are often dangerous to the film). An uneventful process until you stumble upon a lost film or a camera negative or perhaps just a beautiful copy in which the colours are perfectly preserved. And the beauty of those images takes your breath away, the thrill of the discovery repays you for all the hours of boring inspections.

To capture both the routine and the exhilaration, Nicola let three photographers document, without constraint, what they saw behind the scenes of the Cinematek. Xavier Harck, Jimmy Kets, and Marie-Françoise Plissart took their cameras into the vaults, the work spaces, the projection rooms, even the loading docks. The images are gorgeous and radiate the touch and heft of reel after reel, can upon can, in profusion that evokes Resnais’ Toute la mémoire du monde.

Along with the photos are three essays about film archives. They are personal reflections on cinematheques and their place in film culture. Dominique Païni writes (in French) about how access to films changed during his years as director of the Cinematheque Francaise. Erich de Kuyper, filmmaker and novelist, reflects in Flemish on guiding the Amsterdam Film Museum and creating the programs there. I contributed a piece in English that tries to fit my personal research work into broader trends of film archiving. My essay is elsewhere on this site.

The age of impresarios

Langlois is the dragon who guards our treasures.

–Jean Cocteau

In spring of 1973 the New York Times announced that a city board had approved the leasing of a building that would house the City Center Cinematheque. This was to be the American counterpart of the Cinémathèque Française, and Henri Langlois was to be its director.

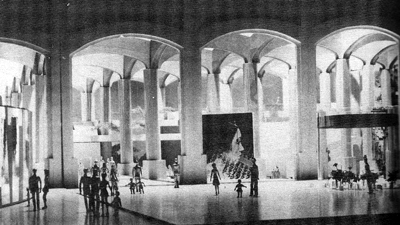

Langlois’ project was as vast and flamboyant as the man himself. An old storage building under the Queensboro Bridge, on First Avenue between 59th and 60th Streets, would be converted into a cathedral of cinema. I. M. Pei would design the new building. (One sketch is above.) There would be three auditoriums, a staff screening room, an exhibition space, a restaurant, a bookstore, and a flower market. Programs would draw upon Langlois’ archive of 60,000 titles, and there would be screenings from morning to midnight, offering as many as fourteen films a day. Langlois predicted that attendance would surpass a million a year.

My own encounters with Langlois, brief though they were, came at just this moment. I needed to see several French silent films for my dissertation work, and in 1972-1973 I wrote to Langlois asking for permission to visit his archive. Thanks to Sallie Blumenthal, we made contact and he gave me permission. In July, during the summer of Watergate, I arrived at the Cinémathèque. An expansive Langlois welcomed me and gave me a tour of the Musée du cinema, which had been somewhat prematurely opened. Jean-Louis Barrault’s costume from Les Enfants du Paradis was draped on a coat hanger nailed to a wall. During my two months in Paris, thanks to Langlois and Mary Meerson, I saw several rare films on Marie Epstein’s viewing table.

I have sometimes wondered if my stay there was an accident of timing. Perhaps as a young American I benefited from Langlois’ high hopes for his transatlantic alliance. Pressed by money problems in Paris, he could imagine that the American branch of the Cinémathèque would vindicate his vision of a motion picture museum without walls: films circulating everywhere, films shown all the time, no film too minor to merit attention. Had the City Center venue come to fruition, it would have overshadowed the Museum of Modern Art, Manhattan’s temple of cinema history. But the project collapsed fairly soon. It required private financing, and during the recession and the oil crisis money was hard to come by.

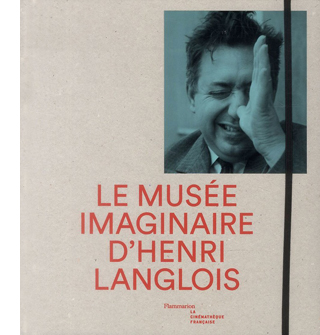

Langlois’ American adventure is just one episode in the tapestry presented in another archive-related anniversary volume: Le Musée imaginaire d’Henri Langlois. Edited by Dominique Païni, this de luxe production accompanied the Cinémathèque’s massive exposition from April to August. If Langlois were still living, he’d be 100 this year, and the sumptuousness of this catalogue is in part a testimony to what he accomplished. He helped make cinema equal to the other arts in cultural significance. But the enterprise is not too serious: Païni has made the volume’s emblem the famous shot, taken by an unknown hand, of Langlois in the kiss-my-ass salute.

The menu is familiar. There are informative essays by various hands, interspersed with illustrations and documents. But the execution is extraordinary. Reminiscent of 1920s publications, on rough paper and with decentered blocks of type, this square volume seduces you into sustained browsing. Moreover, it contains reproductions of artworks related to Langlois and his institution. We have works by Beuys, Chagall, Duchamp, Fischinger, Léger, Matisse, Miró, Picabia, Richter, Severini, and Survage—all connected, somehow to Langlois and cinema. There are frames from Le Métro, a 1934 film by Langlois and Franju., There are guest-book signatures, catalogue covers, correspondence, and much more.

The catalogue of the exposition is accompanied by a slender but no less ingratiating biographical chronology, festooned with still more images. Mais qui est ce Monsieur Langlois? opens with a striking portrait by Henri Cartier-Bresson and ends with the telegram sent by Jean Renoir after Langlois’ death in 1977. “We have lost our guide, and now we feel alone in the forest.”

I met Langlois in the days of rivalry among archives, a good deal of it triggered by him. If you were welcomed to Archive X, and word got to Archive Y, that venue would shun you. Surveying these books, I was struck by their quiet assumption that archives must collaborate on projects and share their treasures. After Langlois, archiving became more cooperative, more routinized, more professional, and–Langlois and his allies would say–more boring. We may not need dragons now. Perhaps, though, we had to go through the turmoil of the Age of Impresarios in order to appreciate why collecting films was so important.

For some ideas on Hou’s visual style, see Chapter 5 of my Figures Traced in Light, this entry, and a discussion of the early films on this site.

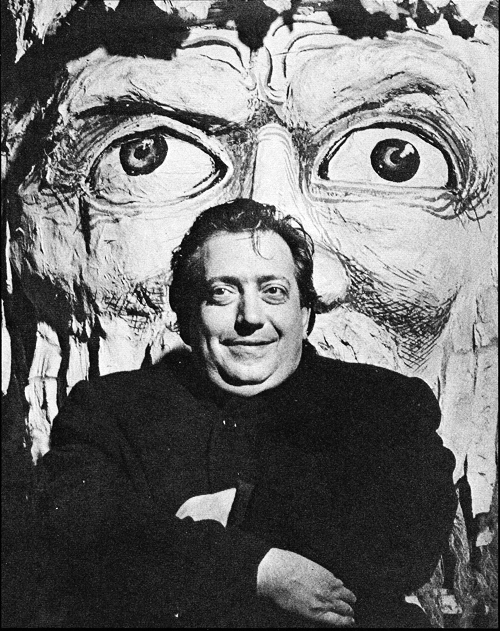

Henri Langlois. Photo by Pierre Boulat.