EXODUS: GODS AND KINGS and the myth of authenticity

Sunday | January 11, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here:

Back in the early 1990s I got interested in ancient Egypt and particularly the Amarna period. I started reading, attending conferences, giving papers at conferences, and eventually publishing scholarly articles. In 2000 I was invited to join the expedition at Amarna, registering statuary fragments. That work quickly grew into matching pieces, reconstructing a considerable portion of an important statue, researching in museums around the world, and now working on a large book on Amarna royal statuary. (You can read a bit about my work in this page of our website–badly in need of updating.)

So I watched Exodus: Gods and Kings with a somewhat different attitude than that of most other viewers. Now I don’t expect all films set in ancient cultures to be 100% authentic in their design and their depiction of events. Considerations of spectacle and general visual appeal take precedence at times. But Exodus goes a bit over the top. Even a one-time tourist to Egypt who was paying the slightest attention to the guide would spot some laugh-out-loud moments here.

The departure from historical reality here led me to think, as I often do, about the ways in which the makers of fiction films set in ancient Egypt and other early cultures tend to try and lend an air of authenticity by hiring an expert consultant who is listed in the final credits.

Something similar happens in educational documentaries of the type shown on The Learning Channel or The History Channel. There several experts may appear in talking-head segments, and additional scholars will be credited at the end as consultants.

My experience, however, is that in at least some cases, consultants’ advice is ignored, even in the documentaries. Filmmakers tend to do what they think will be most appealing to the viewer, and then credit the consultants anyway, as if they had actually guided the filmmakers throughout. I know this partly because several of my teammates and other Egyptologists have complained that it is not uncommon for their suggestions to be dismissed. I have been filmed a couple of times, though I ended up on the cutting room floor in both cases. My chunks of broken sculpture, which tell me a great deal and in some cases are very unusual and important historically, just aren’t visually interesting enough for the public–or so the assumption is. On one of these occasions I pointed out to the filmmakers that one object was more relevant to the point being made than the one they wanted to use. I was told that the one they wanted to and did use would look more attractive. I’m sure a lot of consultants more expert than I hear the same thing.

Too much history

One has to sympathize with filmmakers tackling a tale set in ancient Egypt. Its history just goes on and on.

The date for the unification of Egypt under a single ruler and the invention of the hieroglyphic writing system that made its centralized administration possible keeps getting pushed back as more discoveries are made. Now it’s at about 3100 BC. Pharaonic Egypt ended in 30 BC with the death of Cleopatra VII Philopator (yes, that Cleopatra) when she committed suicide, reportedly using a poisonous snake. To give a vivid indication of how long pharaonic Egypt lasted, Cleopatra lived distinctly closer in time to us (just over 2000 years) than she did to the building of the Great Pyramids of Giza (about 2600 years earlier). And those pyramids were built about 500 years after that unification I mentioned.

The challenge for filmmakers is that many of the things we think of as most emblematic of ancient Egypt happened far apart in time. The Great Pyramids of Giza were built around 2600. The introduction of horses and chariots was–well, nobody knows exactly, but perhaps some time in the 1640 to 1550 BC range. Yet filmmakers cannot resist the temptation to have people dashing about in chariots as they supervise the building of the Great Pyramids. Howard Hawks’s Land of the Pharaoh does it. Exodus: Gods and Kings does it. It looks good, but in modern terms it would be sort of like William the Conqueror checking his email to see how preparations for his invasion of Britain were going.

Apart from the problem of Egyptian history, Exodus mixes two different genres of story. The Exodus story is a myth based solely on texts, with no archaeological evidence to confirm it. Ancient Egyptian history really happened. That history can be portrayed authentically, while the Exodus story can be portrayed faithfully. There’s a difference. Moreover, even people who believe that the Exodus really happened can’t agree at what point in that history it occurred. Probably the most popular choice for the Pharaoh of the Exodus is Ramses II, and the filmmakers have settled on that. He’s not called “Ramses the Second” in the film, and indeed ancient Egyptians didn’t think of their kings as numbered. Still, the fact that his father is Sety indicates that the Ramses in the movie is the second of the eleven Ramses that sat on the throne of Egypt over the years.

Absolute chronology is impossible to determine for ancient Egypt, but best estimate is that Ramses II reigned from 1290 to 1224 BC. (He lived to be 97.) That’s Nineteenth Dynasty, New Kingdom. The period I study is roughly 1353 to 1335, the reign of Akhenaten, who is Eighteenth Dynasty, New Kingdom, so not all that far apart by Egyptian standards. The late Eighteenth Dynasty and early Nineteenth were the pinnacle of Egyptian power and wealth: perfect for a sword-and-sandal spectacle.

Yet in making Exodus, the filmmakers have not solved the problems I’ve just mentioned. Time and space are oddly warped, and design concerns have trumped authenticity to a considerable degree.

Egypt compressed

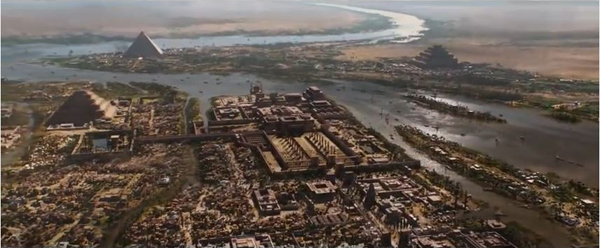

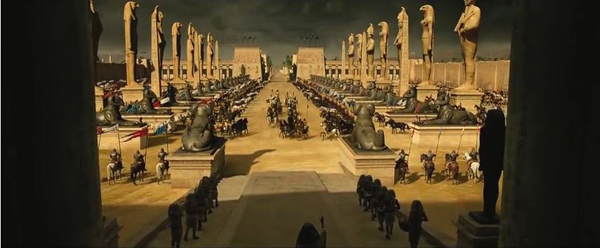

Perhaps the strangest aspect of Exodus: Gods and Kings is how it mashes together not only things from different periods but also localities that are actually many miles apart. The early part of the action is set in Memphis, which was genuinely the administrative capital of Egypt during much of its history. See the image at the top, which gives the best view of the city’s layout. The earliest pyramid ever built, the Step Pyramid of Djoser (constructed somewhere around 2630 BC and probably the one over on the left in the image), is part of the necropolis of Memphis, but it’s up on the high desert, well away from the city, which is down in the cultivated area. And what is that other step pyramid doing on the other side of the river? There was only the one step pyramid, and all the pyramids built as tombs for the pharaoh were on the same side of the river, the west. The pointed pyramid in the distance has been transported from Giza to Memphis. Admittedly, that’s only a distance of about fifteen miles.

But the pyramid is also shown under construction. Ramses II would not have built a pyramid for his own tomb, since long before that point pharaohs had started using rock-cut tombs in what is now known as the Valley of the Kings. That’s where he was interred.

In the film, the palace of Sety and later of Ramses is modeled on the temple of Amun at Karnak, way down in Luxor (about 350 miles away). The massive columns of the hypostyle hall, one of the most familiar tourist sights in the country, were indeed built by Sety and Ramses, but it’s a temple, not a palace. Temples were built largely or entirely of stone in this period, while palaces were mainly built of mudbrick and painted mud plaster. We don’t know nearly as much about palaces as we do about temples, because they tend not to survive very well. Pharaohs tended to travel around, staying in palaces built for specific purposes, rather than to erect one giant one to call home.

The road running out from the palace down which Moses, Ramses, and other leaders of the army depart is lined with criosphinxes, sphinxes with the heads in the form of a ram, the sacred animal of Amun (see bottom). These are copied from the criosphinxes that line the sacred ways leading up to Karnak from the west and south. These criosphinxes didn’t have colossal statues of gods standing in between them, though the filmmakers may have added them to give a hint at the multiple gods of the ancient Egyptians. Given the film’s title, one might expect a little more exposition on the gods of Egypt, to create a contrast with Moses’ monotheistic religion. Instead we get almost nothing relating to gods except entrail-reading, which was not practiced in ancient Egypt.

The choice of Memphis as the main city setting is a dubious one. Sety I founded a new city east of the Delta, and Ramses II built it up into the new main royal residence and capital of the country, Piramesse. I mention this not to be nitpicky. In fact, at the beginning of his reign, as he is in the film, Ramses quite possibly was still primarily residing in Memphis. The point really is that the Bible specifies that the Exodus began with the Israelites leaving “Rameses” (spelled thus in the King James translation, “Exodus” Chapter 12, 37). It’s not absolutely certain that this Rameses is identical with Piramesse, but no other candidate has been discovered, and it seems likely. Piramesse lies well north of the Red Sea and due west from the land bridge from Egypt to the Sinai peninsula. Heading straight for Canaan, the Israelites shouldn’t have had to deal with the Red Sea or any parting thereof to get where they wanted to go. Still, it makes a vivid story.

Piramesse is also quite far from any pyramids or other spectacular, familiar Egyptian structures, and out in the flat lands north of the beginning of the Delta. Plus a lot more people have heard of ancient Memphis than Piramesse, so one can understand the filmmakers’ choice of cities.

Familiar and not so familiar mistakes

Another thing that film designers of stories set in ancient Egypt invariably do is to put many of the male characters and even extras in the striped headcloth called the nemes. That’s the one that forms a sort of triangle on either side of the face. Guards, overseers, officials, all wear the nemes. In this hanging scene, for example, the chap at the far left in the frame below has one, as has the man in the middle ground, just to the right of the scaffolding. So do the men lined up at the back of the scaffold. But the nemes was a royal headdress. Only the king could wear it. The royal uraeus, the rearing protective cobra worn above the forehead, was also confined to the king, and during some periods his wife. We see Moses wearing one when going into battle, which would not have been allowed.

And speaking of this scene, hanging was not a method of execution used in ancient Egypt. In fact, execution as such was fairly rare, but someone who rebelled against the state or the gods might be burned alive or impaled. On the whole,  severe punishments involved loss of property or hard labor, like being sent to the pharaoh’s quarries or mines–likely to be a death sentence in itself.

severe punishments involved loss of property or hard labor, like being sent to the pharaoh’s quarries or mines–likely to be a death sentence in itself.

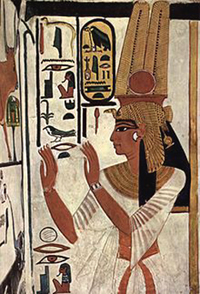

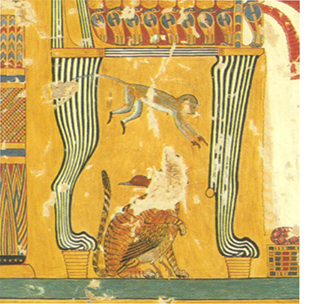

In two or three shots of the palace, we see peacocks wandering around. There were no peacocks in Egypt at this point. I suppose the designers thought that these showy birds would add to the spectacle and the sense of vaguely decadent luxury. There were, however, other options. For example, ancient Egyptian royals and nobility loved monkeys and kept them as pets. They are frequently depicted in reliefs and paintings, mainly in tombs, sitting under their owners’ chairs, though favorite dogs or cats often occupy that spot instead. A particularly lively monkey appears in the image to the left, from the tomb of a prominent Eighteenth Dynasty official, Anen, on the west bank at Luxor. The monkey is leaping under the chair of Queen Tiye, and beneath it is what appears to be a cat embracing a duck in a friendly fashion (left). That seems pretty visually interesting to me.

In the film, Ramses’ army includes cavalry, but ancient Egyptians didn’t ride horses into battle. The troops were either in chariots or on foot. The horses originally introduce d into Egypt were too small to be ridden by someone fully astride their backs. Consequently saddles were unknown in Ramses’ era. The rider had to sit well back on the rump, as Egyptians still do today when they ride donkeys. In the Memphite tomb of Horemheb (last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty or first of the Nineteenth, depending on whom you ask), there’s a rare depiction of a man riding a horse in exactly this fashion (right). He’s probably a groom, taking a horse from one of the chariots visible at the upper right to tend to it elsewhere.

d into Egypt were too small to be ridden by someone fully astride their backs. Consequently saddles were unknown in Ramses’ era. The rider had to sit well back on the rump, as Egyptians still do today when they ride donkeys. In the Memphite tomb of Horemheb (last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty or first of the Nineteenth, depending on whom you ask), there’s a rare depiction of a man riding a horse in exactly this fashion (right). He’s probably a groom, taking a horse from one of the chariots visible at the upper right to tend to it elsewhere.

Exodus: Gods and Kings also dusts off that Hollywood cliché of showing legions of Israelite slaves laboring under the lash to built the Great Pyramids. The main sources of this notion are Herodotus (writing about 2200 years after the event) and the book of Exodus in the Bible (perhaps written close to 3000 years after their construction).

In fact the Great Pyramids were built by paid laborers. Many of these were part of a permanent workforce who lived in a village near the plateau. Others might have been part-timers, such as farmers whose fields were under the inundation for four months out of every year.

The claim in the film is that the Israelites have been enslaved in Egypt for four hundred years. Four hundred years before Ramses II’s reign, Egypt was falling apart, with the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Dynasty pharaohs fighting for control. The country was declining into the Second Intermediate Period, with part of the land controlled by the Hyksos, a foreign group of rulers. There were probably few if any slaves being brought into Egypt at the time, let alone a huge group like the one posited.

Slavery in ancient Egypt is still not fully understood, but clearly it was a more complex and flexible system than the sort of slavery that we think of today. There weren’t all that many slaves in the Old Kingdom when the pyramids were built. The big influx came with the expansion of the empire in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties, when Egypt conquered southward into Nubia and northeastward into the Levant. At that point prisoners of war became the main source of slaves. They would either serve the pharaoh and his institutions or be awarded to the military officers who had served well in combat. Slavery didn’t become the basis of the national economy, ironically, until the Greeks took over.

Slavery took a variety of forms. It could be a punishment for wrongdoers, but it could also be a way of going bankrupt, working off debts by serving the creditor. There is evidence that slaves had legal rights, such as owning property. There are recorded cases, perhaps exceptional, of slaves gaining training in professional skills, including writing. Some could rise to management positions, even supervising freemen in their masters’ estates. In some instances, slaves married or were adopted into the families they served. Slavery covered a wide range of circumstances, but it didn’t extend to the sort of mass oppression portrayed in Exodus: Gods and Kings.

I could go on, but a few more brief examples should suffice. The Great Sphinx, which is located in front of the central pyramid at Giza, is placed out in the desert instead. Colossal statues of Ramses were not built of individual small blocks of stone. Even his collapsed colossus at his mortuary temple, which weighed about 1000 tons when intact, was made of a single giant piece of granite. Huge sphinxes would not be built in the middle of residential areas, let alone slave dwellings, as are the ones we glimpse in the film.

And finally, the golden helmet that Ramses wears into battle is based on a queen’s protective vulture crown. His wife, Nefertari, would have been the one to wear such a crown. The real Nefertari is shown wearing several embellished ones, including this one with large plumes and a sun disk, in her spectacular painted tomb. The vulture’s head acts as a uraeus in this case, though it has rather bizarrely been replaced by a snake on the version given to Ramses.

Don’t get me started on the camels.

Research with a little twist

To be fair, the publicity surrounding Exodus didn’t make a lot of big claims to authenticity. There was some attempt, however, to promote its faithfulness to historical fact. The Hollywood Reporter ran one brief paragraph in a piece on possible Oscar nominees for best production design.

Arthur Max, production designer

Before creating ancient Egypt’s Royal Palace of Memphis, Max took a research trip up the Nile to visit the Luxor Temple and the Temple of Amun [i.e., Karnak]. He also made stops at the British Museum, the Petrie Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Egyptian Museum of Turin. The $150 million production spent 16 weeks building large sets at Pinewood Studios, and CG was used to extend their monumental scale. “Each column is 10 feet in diameter and about 70 feet high,” says Max. “All the furniture is hand-built–there’s not a lot of ancient Egyptian furniture around. All the murals are hand-painted in traditional pigments. They even re-created period sculptures like a 42-foot high head of Ramses the Great.

Some of the other design people, however, freely admitted to a concern with flashiness over authenticity. Variety ran a story on the costumes:

Those who have seen Janty Yates’ work with Ridley Scott in period epics like “Gladiator” and “Kingdom of Heaven” know they can expect a feast for the eyes that’s grounded in research, but also offers what she called “a little twist.” Translation? A bit of extra sheen in a metal breastplate, or, in the case of Scott’s biblical saga, “Exodus: Gods and Kings,” dressing Ramses entirely in gold, or making T-shaped garments for the plebes that look “quite hot,” per Yates.

Another Variety story of the same type is very misleadingly entitled “Making It All Look Real” (in the print edition; the online title is “Artisans on Making ‘Exodus: Gods and Kings’ Look Authentic”). In fact, the piece is about how authenticity was sacrificed to design considerations.

Filmmakers strive for period authenticity–up to a point.

Take Ridley Scott’s “Exodus: Gods and Kings.” Set decorator Celia Bobak said she took certain liberties. For example, tables in ancient Egypt were low to the ground–a look that she felt contemporary audiences might find laughable.

Similarly, cinematographer Dariusz Wolski requested the use of silk fabrics to enhance the film’s warm, golden-color palette, even though linen and wool were more period-specific.

Bobak added that materials used for creating the furniture “were anything but authentic,” but were made to look so by a team of painters who paid attention to surface decoration and detail.

Working with production designer Arthur Max, a frequent Scott collaborator, Bobak researched the period by visiting the Cairo Museum and Egyptian archives in Europe. Once the duo established the look of each set, prop makers, graphic designers and carpenters brought everything to life.

Why modern audiences would laugh at low tables is unclear. I suspect that decision had more to do with staging the scene where Ramses threatens to cut off the hand of Moses’ “sister,” which he is holding down on a table top. That certainly would have looked silly with the characters bending over a low table.

Yes, there was an expert consultant

With this sort of personal research and devil-may-care attitude, combined with the highly selective use of actual historical fact, you might assume that the Exodus project didn’t hire an expert consultant. In fact, they did. They didn’t flaunt their consultant in the credits, though, as such films tend to do. I scanned the credits for the name Alan Lloyd, but I didn’t spot it. It must be there somewhere, since it’s listed on the imdb Full Cast and Crew for the film. There it’s way down at the bottom, under Other Crew:

Dr. Lloyd is listed as “technical advisor (Doctor),” which might convey the impression that he was on the medical team. I don’t know why the filmmakers buried him in this fashion, since Dr. Alan Lloyd is an actual, reputable Egyptologist. He’s currently the president of the Egypt Exploration Society, which has been a major British institution fostering Egyptological work since 1882. He retired from the University of Swansea in 2006, with a substantial record of publication and other scholarly activities. His specialties include Herodotus, the Graeco-Roman period in Egypt, and ancient warfare.

Dr. Lloyd also is a big film fan and admires Ridley Scott, as an interview with him on the writing studio site reveals. There he expresses enthusiasm for the film and the experience of working on it. In particular he speaks of the care taken concerning texts:

One particularly clear indication of this was that they continually came back to me to provide them with copy for Egyptian texts, and this was sometimes hieroglyphs, and this I provided them with, and indeed they used it.

They also, at times, wanted material in hieratic, which was the script that was normally used for letters and documents, and I produced that material for them.

Particularly interestingly, and I don’t know how many people in the world would pick up on this, or even whether it was used, but they wanted text of the Ten Commandments, but not in English.

They wanted it in Hebrew and I gave them the Hebrew text written in the old Hebrew alphabet, not the one that everyone is familiar with. It is the proto-Hebrew alphabet, which is very different.

All the texts in the film flitted by so fast that even an expert couldn’t judge them, but I assume they were accurate. We get one glimpse of Moses writing the Commandments on a tablet, but the view is from opposite him and we see the writing upside down. (By the way, in the Bible, didn’t the Lord himself write these?)

Oddly, toward the end of the production, the filmmakers showed Dr. Lloyd only selected sequences from the film. The same interview continues: “Professor Lloyd has seen footage from the film and says that some of the sequences he watched, including the Battle of Kadesh and the plagues visited on ancient Egypt by an angry God, are ‘brilliantly’ realized.”

To be sure, the long montage sequence of the plagues is probably the best thing in the film. Moreover, given Dr. Lloyd’s expertise in ancient warfare, it seems likely that he was consulted particularly on the battle scene. It’s certainly more authentic than most of the film’s other scenes. Six-spoked chariot wheels, yes. Plumes on the royal horses’ heads, yes. Bows and arrows, yes. The chariots themselves look fairly close to surviving ones from the New Kingdom. My guess is that Dr. Lloyd pointed out that cavalry was not used in that period but was told that showing warriors riding horses (with saddles) was more visually interesting than mere foot soldiers.

Perhaps Dr. Lloyd was not shown the entire film because of all the inaccuracies in the other scenes. Or perhaps I am being too suspicious.

Hollywood remains in an ambiguous position in regard to historical authenticity, especially in spectacular tales set in ancient times. It plays well in the publicity, but when the designers come up with their visions, it’s awfully easy to dismiss it.

A final comment

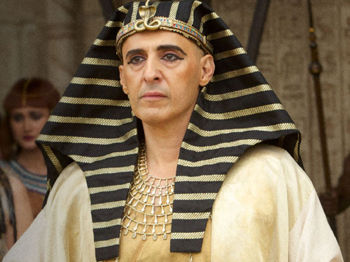

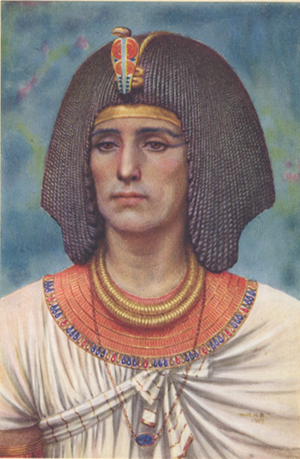

There has been much criticism of the filmmakers for using white males for the lead roles. True, it’s hard to think of Christian Bale and especially Joel Edgerton as an ancient Canaanite or Egyptian. But to give the film some credit, the moment I saw John Turturro as Sety I, my unexpected reaction was, Wow, he looks like a Ramesside pharaoh. Specifically, like Sety I.

How can we know? For a start, Sety’s mummy happens to be one of the best-preserved that has come down to us. Even so, it’s hard to tell from a mummy what the man looked like, though he obviously had a beaky nose, a long chin, and prominent, high cheekbones. In the early 20th Century, artist Winifred Brunton studied Egyptology alongside her husband. They worked in Egypt, and during that time she painted a set of portraits of the pharaohs and their families, based on paintings, sculptures, and mummies. They’re actually fairly plausible as conceptual paintings. Although they’re not scientific evidence, they’re still held in some regard by Egyptologists–though obviously the depiction of the skin color of the ancients does look too European. Her portrait of Sety I is at the right below. She shows the pharaoh as a younger man, but to me the resemblance is there.

The only source I could turn to for frames from the film was the set of online trailers. I can’t be entirely sure that all of my illustrations are in the final film, since occasionally shots from the trailer get dropped.

The photo of Ramses’ helmet was one of many of his golden costume taken by blogger Jason in Hollywood during the current “23rd Annual Art of Motion Picture Costume Design” exhibition, which takes place in the pre-Oscar period.

For those interested in birds in ancient Egypt, a catalogue of a recent exhibition at the Oriental Institute in Chicago is available as a pdf online for free. No peacocks, but storks, pelicans, hoopoes, geese, and many more, as beautifully rendered in tomb paintings and other ancient artworks.

Anyone visiting Bologna, whether for Il Cinema Ritrovato or any other purpose, can wander over to the Museo Civico Archeologico, just off the Piazza Maggiore, and see the original of the relief of the horse-riding groom and other magnificent scenes from the tomb of Horemheb.

For a good, brief Associated Press summary of evidence against the Great Pyramids being built with slave labor, see here. For a longer but accessible account of the work of Mark Lehner, who has long excavated at Giza and discovered the village of the pyramid workmen, see here.

Winifred Brunton’s portrait of Sety I appears in her Kings and Queens of Ancient Egypt (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1926).