The waning thrills of CGI

Sunday | May 24, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here:

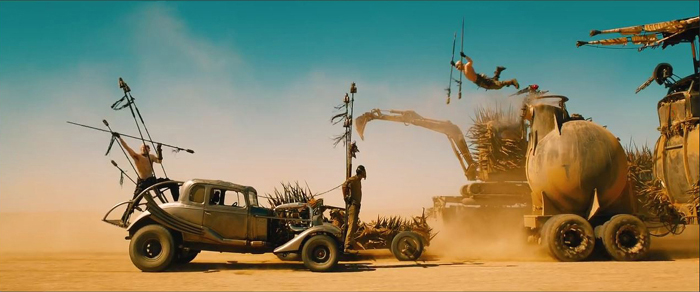

There have been rumblings lately about the surfeit of CGI-heavy films, especially superhero movies, and about a certain monotony in the results. Critics and fans are hailing Mad Max: Fury Road, in no little part because George Miller did stage much of the action, with real fantasy vehicles and hair-raising stunts, and employed CGI only when necessary. Among the diehard Peter Jackson fans over on TheOneRing.net, many argue that the emphasis on practical effects over digital in the Lord of the Rings trilogy should have been carried over to the Hobbit trilogy, despite the advances in CGI technology in the nine-year gap between them.

Earlier this month, Variety‘s Brian Lowry published an editorial laying out the problem. He concentrated on the superhero movies that have increasingly come to dominate the tentpole level of big-studio filmmaking:

The ability to mount enormous battles featuring multiple super-powered characters, however, has become its own trap. And while the results can be visually astounding, the movies regularly feel as lifeless and mechanized as the technology responsible for bringing those visions to fruition.

The why of it remains something of a mystery, but the outcome is frequently a hugely expensive–if often enough quite lucrative–tentpole release that certainly puts the money onscreen, yet nevertheless proves more numbing than exciting, even during what should be the show-stopping sequences.

The original “Avengers” was mostly a happy exception, even with its prolonged alien-invasion climax. “Age of Ultron,” while ambitious in exploring relationships among characters, becomes drearily repetitive as the heroes mow down another CGI horde, this time consisting of artificially intelligent robots.

[…]

The pattern has become predictable. “Iron Man,” a terrific movie overall — particularly in capturing the origin story — degenerated into a mundane brawl between two armor-clad characters. Ditto the “Hulk” reboot with Edward Norton, which culminated with the title character’s ho-hum showdown with another green behemoth, the Abomination.

One can argue, in fact, that the much-maligned second “Star Wars” trilogy sacrificed an element of its humanity in George Lucas’ embrace of a wholly digital filmmaking approach. At a certain point, watching droid armies being whacked to pieces begins to yield diminishing returns.

Put more simply, just because CGI wizardry allows you to do something, whether hoisting an entire city into the air or leveling skyscrapers willy-nilly, doesn’t always mean you should. Because while the box office figures might suggest otherwise, there is an audience out there that’s weary of these movies precisely because of the hollow quality to the inevitable final 30 minutes of unrelenting mayhem.

This struck a chord with me, because since the beginning of the year I have seen trailers for several CGI-heavy films. (How many of them begin with an ominous “helicopter shot” high over a CGI city, usually at night?) Most of them melt into each other in my memory, but I do recall that they included Insurgent (the teaser, below left) and Jupiter Ascending (trailer #3, below right).

My reactions to the Insurgent and Jupiter Ascending images were: 1) another burning cityscape with a CGI person flying through the air, and 2) wild horses couldn’t drag me to these.

Compare these two frames with the image at the top of this entry. My reactions to the Mad Max: Fury Road teaser, which I only saw in HD on my computer, were: 1) what a gorgeous shot, 2) why is that guy doing that–he’s crazy, 3) George Miller and all these other people are crazy, and 4) I must see this film ASAP. The same qualities attracted me to The Road Warrior, but this time Miller had a far bigger budget, allowing him to create more vehicles and make them more elaborate.

The increasingly same old-same old quality about superhero films extends to science-fiction films and dystopian future ones.

CGI is a marvelous technology and has been used to create wonderful films, scenes, and characters. Gollum remains one of its most successful and memorable creations. I suspect that many, like me, remember that initial jolt of amazement in the scene in The Two Towers when the mild “Smeagol” and villainous “Gollum” sides of his nature talked to each other, and a sudden switch to shot/reverse shot made his split visible, as if he had two bodies:

It was a brilliant way to handle the scene, but it also depended on us accepting Gollum as a character on the same plane of existence as Frodo and Sam. Yes, the technology for Gollum was improved for his reappearance in The Hobbit, but it wasn’t dramatically better, and the first trilogy was the real breakthrough.

Smaug was another creation where one could hardly deny that CGI was used with astonishing complexity and skill (see bottom). The same is true for The Dawn of the Planet of the Apes and The Rise of the Planet of the Apes (also with effects by Weta Digital, which also managed to fill in scenes involving the late Paul Walker in Furious 7 without barely anyone noticing).

Lest all this become too Weta-centric, I also have seen the teaser for Robert Zemickis’ The Walk a few times. Again there’s a computer-generated cityscape, as in Insurgent and Jupiter Ascending, but the effect is quite different. It’s an attempt to create realism in a story based on actual events; the actor obviously can’t be placed high above New York, and the Trade Towers are gone. The effect is anything but clichéd. That I was to see, too.

Another well-reviewed current science-fiction film, Ex Machina, uses CGI in an original way. David liked it less well than I did, but whatever one thinks of the film as a whole, the robot character Ava is not something we’ve seen on the screen before–at least, not done this way.

Historically, any art form goes through cycles. Hugely successful films will give rise to many imitators, and imitation eventually leads to cliché. The question is, will the filmmakers called upon to make big effects-heavy films make the effort to use CGI in an imaginative way? With sequel after sequel in the largest franchises already planned by the studios for years into the future, will the apparent assumption that flashy CGI is enough to attract the action-movie crowd prove wrong?

The madness of Mad Max

Despite the critics’ emphasis on the practical effects and real locations in Fury Road, it should be pointed out that Miller used quite a bit of CGI in the film. Indeed, he was no stranger to digital effects. For Babe (1995), his team used CGI to achieve the most realistic talking animals in films to that time. (Miller produced and wrote the script, with Chris Noonan directing; he directed Babe: Pig in the City.) Previously talking animals were usually done with puppets and animatronics, but Miller’s team used 3D scans of animals snouts and muzzles and manipulated the results. Babe won the 1996 Oscar for best visual effects. There were no exploding cities, giant armies, or battling superheroes, but experts recognized those moving animal mouths as cutting-edge stuff.

In Fury Road, CGI is used for effects that would be difficult, impossible, or prohibitively expensive otherwise. Furiosa’s missing left wrist and hand are an obvious example, as is the massive sandstorm that hits the fugitives and pursuers.

The blue night scene was shot day for night and then enhanced digitally, presumably with tinting and the addition of stars. The city which is the Citadel’s source of gasoline and is supposedly Furiosa’s goal as her truck sets out early in the film, is shown on the distant horizon but clearly was not built, since none of the action takes place there. The Citadel scenes were done in Australia, while most of the desert material was shot in Namibia. Some parts of the Citadel were built full-scale (e.g., the winch room), while green-screen replaced by digital set extensions supplied the rest. I think I spotted some digital matte paintings in some of the landscapes. But on the whole, Miller stuck to real locations, and most of the scenes of the chases were done with real vehicles and actors, chasing each other around the Namibian desert.

Miller commented, “We don’t defy the laws of physics–there are no flying human beings, no spacecraft–so it doesn’t make sense to do it as CGI. We’ve got real vehicles and real humans in a real desert, and you hope that all that texture will be up there on the screen.” Miller had in fact assumed that he would have to create the “pole cat” sequence, which has men perched on long, swaying poles atop speeding vehicles (above). Action unit director Guy Norris, however, shot a test scene on video, with no CGI. Miller was thrilled: “There were 10 pole cats swaying, coming down the road at speed, all of them on cars, and Guy was on one of the poles filming them. I choked up. I thought, ‘Wow, it’s real. It’s absolutely real.”

According to Simon Gray’s “Max Intensity” in the latest American Cinematographer (not yet online), “Months of rehearsals enabled the stunt crew to perform their choreographed sequences while the vehicles traveled at speeds up to 50 miles an hour.” (AC, June 2015, p. 42)

The reality of it comes through, as in this scene of one of many explosions. The stunt man flinching in the foreground is not the sort of thing you’d see if this were all being faked.

And some of the stunts are not all that different from what we saw in The Road Warrior or Beyond Thunderdome, both made in the pre-CGI days. This scene, for example, among the best in the film, where a motorcycle gang chases Furiosa’s rig.

One reason why Fury Road looks so good is results from Miller’s and and his cinematographer’s decision to avoid the look of most post-apocalyptic movies. Anne Thompson describes their approach: “The cliches of the genre were to desaturate the cinematography. So he and great Australian cinematographer John Seale (dragged out of retirement), saturated the color. ‘We were able to change the skies, and go against the idea that because it’s the apocalypse, there’s no longer any beauty in the world.'” (AC, June 2015, p. 48)

There are desert areas of Africa where the sand is the rich, peachy color that appears in the film. The Namibian desert, however, is not so colorful.

(George Miller, in the official Warner Bros. making-of publicity short)

The film’s senior colorist, Eric Whipp, describes the challenge of differentiating the largely brown, beige, and grey colors of the costumes and vehicles from such backgrounds: “The desert sand in Namibia is, in reality, closer to be gray color, but pushing it toward rich gold colors complemented the characters and vehicles, providing a strong, graphic look. The only other dominant color in the film was blue sky, which we embraced.”

The transformation of the desert into rich yellow and orange tones was done with what was obviously aggressive digital color grading. It runs marvelously counter to the dull blues, browns, and grays that form the dominant look of so many action films.

[May 31: On fxguide, Ian Failes has posted an excellent piece that lays out the practical vs. the digital effects in Fury Road.]

LOTR vs. The Hobbit

Reading Lowry’s comments made me think of Andrew Lesnie, who died recently at the young age of 59. Lesnie had unintentionally played a small but pivotal role in my attempts back in 2002-2003 to get permission to interview the Lord of the Rings filmmakers for my book, The Frodo Franchise. I needed to contact someone high in the production who could be a sort of sponsor for me, helping to gain New Line’s cooperation. The only people I figured could do that would be producer Barrie Osborne or Peter Jackson or Fran Walsh.

In November 2002, I was at a conference in Adelaide, Australia and met Annabelle Sheehan, who at that time was an administrator at the Australian School of Film, Radio and Television. When I told her of my potential project, she offered to put me in touch with Lesnie. I hesitated before responding. I knew that it would be wonderful to interview him, but my subject didn’t relate to cinematography at all. Moreover, he wasn’t in a position to sponsor such a project. Then Annabelle offered to introduce me to Barrie Osborne, which subsequently happened via email. The project became real at that point.

I’ve always regretted that I had no excuse to interview Lesnie. From interviews and his appearances in the supplements for the extended DVD editions of LOTR, he seems a genial man. I also admire the cinematography for LOTR. There’s a great variety in the lighting schemes, and he contributed some very striking moments to the film.

It’s of course very difficult to pin down exactly what Lesnie’s contributions to LOTR were in many scenes, given the considerable dependence on CGI. Still, I think he probably had more affect on the final look of LOTR than he did on The Hobbit. As the three parts of The Hobbit came out, it became increasingly clear that there were no shots or sequences that could stand comparison with the best things in LOTR. I think of well-conceived, dramatic shots like the one in The Fellowship of the Ring where a scene begins with a bucolic view out over a misty morning in the Shire, which is suddenly interrupted by ominous music and the entry from offscreen of one of the Black Riders’ horses.

Another shot I admire is the first exterior after the long sequence of the passage through the Mines of Moria in Fellowship. Gandalf has just fallen into the abyss with the Balrog, and the others flee. The cut to an extreme long shot of the rocky terrain (filmed on Mt. Owen) outside the eastern gate to the Mines is jolting, seemingly switching from a color film to a black-and-white one. A trace of green plants at the lower left is virtually unnoticeable, and only as the camera arcs around to follow the remaining Fellowship’s movements away from the gate (which was added digitally) does a bit of blue sky appear at the upper right and eventually the green of the landscapes in the distance.

Although there are plenty of New Zealand locations in The Hobbit, I can’t think of any that are used as effectively as some of the ones in LOTR–most memorably the Edoras set, which was built full-size on Mount Sunday on the South Island. The swooping helicopter shots around the rocky promontory, with the snowy mountains revolving slowly around it, became iconic moments in the film.

Viewers might think that those background mountains were added digitally, and certainly some scenes, including the ones set at Orthanc, did have backgrounds built up of mountains from a variety of places. The extreme long shots of Rivendell are a patchwork of elements. Not so for Edoras, however. David and I were privileged to fly around Mount Sunday in a small plane–after the Edoras set had been removed–and we saw more or less what one sees in the film.

It was a different time of year, November (the Southern Hemisphere’s equivalent of May), but the mountains are clearly the same ones.

There was a helicopter camera team, so Lesnie might have had nothing to do with these circling shots, nor with the mountain photography for the magnificent Beacons Sequence in The Return of the King (to which the fires were added digitally).

Again, there is nothing to compare with this in The Hobbit, which, I would say, suffers from having so many sequences with CGI-created landscapes.

The only really memorable shot I can think of from The Hobbit is entirely digital, the emergence of Smaug from Erebor, covered in gold, at the end of The Desolation of Smaug. He bursts through the door and soars up away from the camera, shaking the gold off in sparkling droplets.

The shot of the dragon’s death is nearly as impressive, as Smaug falls slowly downward away from the camera.

The problems with The Hobbit arise, I think, because so much of it, especially in the third part, has been conceived as almost entirely digital. Compare these two pre-battle moments from The Return of the King and The Battle of the Five Armies.

As Théoden addresses his troops before their charge during the Battle of the Pelennor, we are clearly watching real riders on real horses, their spears held at various angles. To be sure, the MASSIVE program was used to multiply horses and riders, but primarily in the extreme long shots. Hundreds of real ones were used in the scene. In the background we again see impressive non-CGI snow-covered mountains. There are four characters here about whom we care: Théoden, Éowyn, Merry, and Éomer. The Battle of the Five Armies shot of Thranduil’s troops, in contrast, involves perfect ranks of anonymous Elves, moving in synchronization. There is no actual landscape behind them, just vague patches of blue, brown, and white.

MASSIVE was used here as well, but for far more figures. Wasn’t the program devised to allow digital “extras” to move independently of each other rather than replicating a very limited number of gestures? It’s ironic, since in the film’s endless battle, characters moving in synchronization seem to be the rule. See the moment when the dwarves assemble their shields into a wall against the orcs, with Elves leaping effortlessly over them.

Which brings up the matter of seemingly weightless characters and creatures. There has been much discussion of the fact that Legolas and Tauriel leap about, stand on other characters’ heads while fighting, and bound up collapsing stone staircases. Admittedly, Tolkien says in the blizzard scene of The Fellowship of the Ring that Legolas’ “feet made little imprint in the snow.” But even assuming that Elves are very light, some of the antics in The Hobbit look plain silly.

And it’s not just Elves that zip about in this fashion. Partway through the Battle of the Five Armies, large rams appear out of nowhere. (I gather that their presence will be explained in the extended edition.)

Thorin, Kili, Fili, and Dwalin ride the rams up the sheer pinnacle to reach Azog’s command post. The rams bounce weightlessly and effortlessly up the steep cliffs, looking more like ping-pong balls than heavy animals. Indeed, gravity seems to be defied quite a bit in the films–even putting aside from the fact that the characters are able to survive impossibly long falls without a scratch. I can’t think of cases in LOTR where such things happen.

Much has been made of the fact that The Hobbit contains many echoes of LOTR, in terms of characters, scenes, and even specific repeated lines. I’ve complained about that myself. Yet there are many fans who prefer The Hobbit to LOTR–many of them fangirls obsessing over Richard Armitage (Thorin), Aidan Turner (Kili), Dean O’Gorman (Fili), and/or Lee Pace (Thranduil). Such fans proudly point to the “fact” that the second trilogy had higher box-office totals than did LOTR. In unadjusted dollars, yes. In adjusted dollars, LOTR made considerably more, and that without the benefit of 3D surcharges. I suspect this disparity arose from the fact that LOTR was so extraordinarily original, and because it balanced CGI and practical effects so effectively. The Hobbit tipped far in the direction of CGI, and it shows.

Many studios and filmmakers will continue to rely on the standard look of action/sci-fi/fantasy CGI, at least until it becomes so obviously repetitive that audiences lose interest. But films like Fury Road and LOTR offer models of how CGI and practical effects can be balanced for a much livelier film.

[April 18, 2016: Ex Machina, to the surprise of many, won the Academy Award for best special effects. This was probably because it was so original in its use of effects. After all, most special effects doesn’t equal best special effects.]