Archive for 2016

It’s all over, until the next time

Our Little Sister (Kore-eda Hirokazu, 2015).

DB here:

The perennial Silly Season topic, The Death of Film, is back.

In June, Huffington Post‘s Matthew Jacobs announced “The death of Movies As We Know Them.” He laments the loss of “solid storytelling and bankable stars.” In August, Brian Raftery asked: “Could this be the year that movies stopped mattering?” The author argues that now movies are “Something to Do When the Wi-Fi’s Down.” Echoing the virality theme, Ty Burr announced that two albums, Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” and Frank Ocean’s “Blonde,” “came packaged with better movies than anything in theatres.” For Burr, the summer season confirmed that audiences are more interested in grazing among YouTube clips and luxuriating in eight-hour video serials than watching a feature film. “The two-hour movie, especially in its larger and more commercial form, is becoming a relic.”

Richard Brody eloquently replied to Raftery, noting Beyoncé’s debt to Julie Dash and Khalik Allah’s films. Brody has been around this block before, as I noted in a 2012 blog entry.

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

But after four years, maybe things really have deteriorated. So let’s get specific. What’s really going down the tubes? The theatrical side of the industry? Quality? Cultural cachet?

Movies, your best entertainment value

Bar area of Orange Cinema Club, Beijing.

Let’s look at some current evidence about the industry, thanks to the redoubtable Cinema research division of IHS Media Technology.

The newest symptom of cinema’s demise, according to many, is the rise of Netflix and other streaming platforms. Serial TV is attracting a lot of attention, true, but streaming has long relied on licensing feature films from studios, independents, and overseas companies. TCM and Criterion are launching FilmStruck as a new channel chock-full of classic films from Hollywood and elsewhere. Amazon and Netflix have also begun acquiring and financing features to guarantee a supply of those two-hour films that for some reason people still want to watch.

But what about movies in theatres? Actually, things are pretty robust. Despite everybody viewing at home and on the go, for many years theatre growth has been phenomenal. In 2015 the world added about 12,000 screens, hitting a new high: 153,163. Not counting all our “second screens” (and third), there are more movie screens now than ever before.

By the way, those of us, me included, who worried that the rise of digital exhibition would cause a drop in screens were wrong. Digital was a shot in the arm to theatrical exhibition, and it made 3D a viable platform. That format shows signs of growth, chiefly because of China, and now 16-20% of box-office grosses come from 3D screenings.

In keeping with the expansion of exhibition, for the last decade, the global box office has risen steadily. Almost every year sets a record. The new height is $37.7 billion for 2015, and it seems likely that 2016 will beat that.

As for number of admissions, 2015 also set a record: 7.4 billion, a jump of 13% over 2014. This is a bit more than one ticket for every man, woman, and child on earth. The first half of 2016 is ahead of the same period last year.

Of course revenues don’t equal profits. Jacobs is especially concerned that some big films have been losing money in their domestic theatrical run. But most films lose money in that run. For a long time, ancillary markets (DVD, overseas cable, merchandising, etc.) made up for the deficits. More and more, overseas theatrical is helping in a big way. In a recent rundown, of the summer’s top twenty hits, a print story in The Hollywood Reporter indicates that foreign grosses outweigh US/Canadian ones in most cases, and sometimes by a lot.

For example, big as Captain America: Civil War was in the US, 65% of its $1.1 billion haul was due to the offshore market. X-Men: Apocalypse got half a billion theatrical, 71% of which came from the international audience. Ancillaries will still need to kick in, given the mammoth budgets of films like these, but those ancillaries piggyback on theatrical visibility. As ever, the big pictures pay for a lot of lesser films.

Moreover, so many costs are buried or dispersed in overhead, debt service, tax incentives, deferred payments, far-fetched studio expenses, and the like that it seems hard to know what final profits really are. Nor will we know what, if any, profits are yielded by films from countries with subsidized film industries.

There are many things to worry about in the exhibition business, but it doesn’t seem on the verge of collapse. Let’s keep a sense of proportion. Here is what the death of “our cinema” might really look like.

Theatre admissions fall 45% over six years. Studio profits fall 80% over the same period. One-sixth of theatres close. Major overseas markets refuse to remit the earnings of Hollywood films. Audiences turn increasingly to other leisure activities.

This was the state of the American film industry in 1953. The prosperous war years, culminating in the all-time admissions high of 1946, were over and the studios went into sharp decline. Thanks to the 1948 Supreme Court “Divorcement Decree,” the studios lost control of their theatres, relinquishing not only valuable showcases for their product but also millions of dollars of prime real estate.

Yet as we know, 1953 didn’t end cinema, not even American cinema. As the old studio system waned, a new one eventually replaced it. In the process, Hollywood continued to make major films. Filmmaking abroad—in Asia, Europe, and South America especially—flourished. Film festivals sprang up, and a new young public proved eager to watch movies from a variety of cultures. Avant-garde and documentary movements gained traction, partly because of the widespread dissemination of 16mm.

No one, so far as I can tell, predicted the end of cinema, or Hollywood, because of the 1947-1953 crisis. That person would have looked very foolish. Things today aren’t nearly so severe.

Long, hot summers

What about quality? A. O. Scott points out that the way to quell fears for the End of Good Cinema is to go to a film festival. It’s good advice that we’ve given as well. Richard Brody, who has I think seen everything, responds to Raftery by reminding us of many valuable films that the naysayers ignore. Another way to remain calm is to look at a little history.

What about quality? A. O. Scott points out that the way to quell fears for the End of Good Cinema is to go to a film festival. It’s good advice that we’ve given as well. Richard Brody, who has I think seen everything, responds to Raftery by reminding us of many valuable films that the naysayers ignore. Another way to remain calm is to look at a little history.

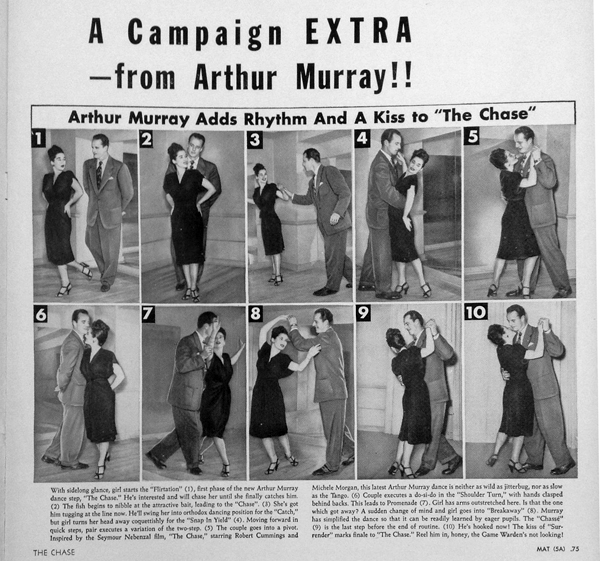

Things often seem grim at summer’s end. Let’s go back fifty years, to the summer of 1966. In those days, the blockbusters and prestige pictures were saved for fall and winter. Indeed, the blockbusters were largely the prestige pictures, the adaptations of novels and plays. The big grosser of the year was Hawaii, released in October. Two others were The Bible: In the Beginning (September) and A Man for All Seasons (December). But two of the top-grossers hit the jackpot in the summer: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (July) and Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN (June).

Pause on this last title. Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN was an indisputably lowbrow hit, a Disney comedy starring Dick Van Dyke. The fact that it earned $10.1 million (about $75 million today) might well have set critics worrying about American tastes. Worse, they might have concluded there was no hope, because from 1950 to 1970, twenty Disney films appeared in the annual top five. That record includes not only animated classics but In Search of the Castaways, That Darn Cat, and Darby O’Gill and the Little People–enough to make intellectuals despair of American moviegoers. Robin Crusoe‘s summer success might have seemed another sign of End Times.

Summer 1966 also saw The Ghost and Mr. Chicken, Fantastic Voyage, the remake of Stagecoach, a Bob Hope comedy, the low camp of Batman, and the high camp of Modesty Blaise. The 1966 counterpart to our spate of superhero sagas was a cycle of spy movies, somber or spoofy. The summer yielded Blindfold, Arabesque, and even The Man Called Flintstone. Along with these came Nevada Smith, Khartoum, What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?, This Property Is Condemned, and Wild Angels.

Some of these are well-remembered, mostly by viewers exposed at an impressionable age. For prestige there was and remains Virginia Woolf. For auteurists, there was Three on a Couch and Torn Curtain, and perhaps Modesty Blaise. As for the rest, most were and are still decried as junk.

Things were not looking good for American cinema. The Sound of Music had just won the Best Picture Oscar, a middlebrow shot across critics’ bow, and Pauline Kael was turning angry firepower on the massive threat posed by The Singing Nun. In the summer, the Times lambasted Hitchcock and Jerry Lewis. As far as I can tell, the follow-ups to the Bond boom pleased hardly anybody.

In sum, we forget just how godawful summer movies can be, year in and year out. The few we remember after Labor Day bob up from a river of sludge. We should be grateful for Indignation, Finding Dory, Lights Out, The Shallows, Hell or High Water, Don’t Breathe, The BFG, Kubo and the Two Strings, and probably half a dozen others I haven’t seen. (But not Jason Bourne, which I have.) Ben-Hur wasn’t as terrible as I’d been led to believe.

And of course, everybody’s pumped for the fall, for Snowden and The Arrival and The Birth of a Nation and La La Land and Manchester by the Sea and all the rest. 1966 critics were looking forward as well, but to what? Not only Hawaii, The Bible, and A Man for All Seasons but also Is Paris Burning?, Grand Prix, Any Wednesday, The Sand Pebbles and more spy movies (Gambit, The Quiller Memorandum). Not so exciting by our standards; Big Pictures were more square then.

True, also coming up in the fall of ’66 were The Fortune Cookie, Seconds, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Fahrenheit 451, The Professionals, Loves of a Blonde, and Blow-Up. But even then some critics stayed unhappy. Kael denounced Blow-Up, and Vernon Young intoned: “The party’s over. . . . Another phase of film history, in many ways the most creative, is drawing to a close.” Sound familiar?

Conversation starters and stoppers

End-of-movie writers argue that pop music and Quality Television are usurping the cultural place of film. But I’m skeptical, because I don’t think film is playing in the same arena.

Odd as it sounds, film has never been popular on the scale of other mass media. Before TV, radio listeners far outnumbered film audiences. Via radio and records, a hit tune reached more people than nearly any movie. Even today, radio audiences are surprisingly big. Nielsen reported in 2014 that just in the 18-35 age group, 65 million people listen to radio broadcasts each week. That’s nearly three times the average number of all viewers who attend movie theatres in a week.

Once TV came along, it became another truly mass medium. 73 million people, over a third of the US population, watched the Beatles on Ed Sullivan in 1964. TV is still the big game. More than 20 million people watch The Big Bang Theory each week. It’s reported that 8.9 million people watched the season finale of Game of Thrones in original cablecast, and 23 million in all its iterations. Yet, again, about 23 million people see all the movies playing in a given week.

The plain fact is that visiting a theatre to see a movie has been, throughout most of American history, a middle-class pastime. It’s relatively expensive, and getting more so. It’s not quite niche, not as rarefied as theatre or concert music or novels, but still not on the scale of other media. We ought to expect that memes will spread faster and more pervasively in pop music and television platforms.

Our critics are concerned that films aren’t part of what Raftery calls “the pop-cultural conversation.” “What in popular culture got people excited or even interested over the last few months?” asks Burr, going on to worry that movies didn’t do so. This is a strange criterion for judging films. Hula hoops, Rubik cubes, Chia pets, and Donald Trump’s coiffure have all been part of the cultural conversation. Some good films excite lots of people, and some don’t (partly because those people don’t know of them). And of course many people got excited by films Burr and Raftery considered bad, like Suicide Squad. Excitement may not be a great standard for excellence.

The cultural-conversation gambit suggests that mere popularity needs to be accompanied by a special jolt, the hum of nowness, the throb of hipness. Financially successful films like The Jungle Book or Finding Dory don’t give off much buzz. Where does that special ingredient come from? Apparently, now, the Netizens. It’s natural that critics, who are assigned to surf the waves of mass tastes, would identify important art with what’s trending on Facebook. It’s their job to hop on what’s hot.

Or in truth, help make it hot. When critics treat what’s buzzy as valuable, they agree with marketers, and cooperate with them. How many critics who loved The Dark Knight had been prompted by the campaign that played up “Why So Serious?” and other memes that publicists thought would stick? Kristin has documented how The Lord of the Rings marketers set the agenda for journalists by means of junkets and Electronic Press Kits (above), while wooing fans with carefully judged opportunities to participate online (a “pop-cultural conversation,” for sure). The typical big film is positioned by the marketing campaign, and even unanticipated responses, especially if the film is strategically ambiguous, can feed ticket sales.

The People don’t start the cultural conversation; they react to what they’re given. The conversation is started by the studios, and they try to channel it. They generate the “controversies” about making the protagonists of Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens a woman and an African American man. The critics pick up the story. (Remember: column inches.) Viewers dutifully enter their opinions on blogs, tweets, and comments columns–which the critics then re-spin. As Brody points out of Quality TV, it’s all about expanding discourse, indefinitely. Criticism begets “comments” which beget chitchat. This is less a conversation than a perpetually chattering flashmob.

A side note: I wonder if making cultural buzz a criterion of worthwhile cinema doesn’t owe something to the influence of Pauline Kael. She sent contradictory signals on this score, worrying that audiences were too easily bought off; the industry jollied them into accepting junk as fun. But she thought that one reason to like, say, Bonnie and Clyde was the fact that it was “contemporary in feeling.” It brought into movies “things that people have been feeling and saying and writing about.”

For a moment let’s accept the assumption that worthy movies have some broader cultural impact. How could we measure that? I suggest the Tagline Test. A movie enters the culture when a line becomes instantly recognizable. At its best, the tagline applies to an immediate situation. You step into a startling new setting and tell your friend you don’t think you’re in Kansas any more. You talk about your boss making you an offer you can’t refuse. You’re bargaining and you say, “Show me the money.” TV gives us plenty of catchphrases, of course. (“You rang?” “Not that there’s anything wrong with that.” “Don’t have a cow, man.” “That’s what she said.”) This is one symptom of a show’s buzziness.

When I came up with the Tagline Test, I thought it supported the doomsayers’ diagnosis. I couldn’t think of many memorable lines from films after the 1980s. Had TV taken over the traffic in catchphrases? Crowdsourcing among two fairly diverse populations came up with a big set. Here’s a sample:

Hasta la vista, baby. Houston, we have a problem. That’ll do, pig; that’ll do. I drink your milkshake. The Precious (enunciated in a high voice). With great power comes great responsibility. Stop trying to make fetch happen. She doesn’t even go here. Stay classy. That escalated quickly. The first Rule of Fight Club… 60% of the time, it works every time. Little golden-haired baby Jesus in the crib. Schwing! Coffee is for closers. King of the World! Stay alive; I will find you.

The Big Lebowski is a virtual encyclopedia of them: The Dude abides. Obviously you’re not a golfer. That rug really tied the room together. Nobody fucks with the Jesus. So too Napoleon Dynamite: Whatever I feel like I wanna do GOSH! I’m pretty much the best in the world at it.

Maybe you don’t agree that these are all equally common; I didn’t know about the Mean Girls and Napoleon Dynamite ones. But all I need to show is that recent movies have entered the “cultural conversation” quite literally. Maybe it just takes months or years for movie taglines to replicate in everyday life. Anyhow, those who want movies to get all buzzy don’t have to worry. With Oscar season upon us, the frenzy will begin. In fact it already has, with Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation.

Who’s we?

In talking about “our” cinema, I’ve been too glib, though this angle fits with an assumption of the death-knoll critics (“Movies as We Know Them”). Of course, Jacobs, Raftery, and Burr all acknowledge that Hollywood isn’t making movies just for us; it’s a world industry. People elsewhere (many recently arrived in the local equivalent of the middle class) seem keen to participate in American popular culture, with fashion, music, TV, and websites. Hollywood entertainment, lame as it often is, is part of being cosmopolitan.

In talking about “our” cinema, I’ve been too glib, though this angle fits with an assumption of the death-knoll critics (“Movies as We Know Them”). Of course, Jacobs, Raftery, and Burr all acknowledge that Hollywood isn’t making movies just for us; it’s a world industry. People elsewhere (many recently arrived in the local equivalent of the middle class) seem keen to participate in American popular culture, with fashion, music, TV, and websites. Hollywood entertainment, lame as it often is, is part of being cosmopolitan.

Still, maybe it’s time to admit that we don’t own Hollywood. Maybe we never did, but it seems clear that with globalization “our” popular cinema is becoming something else–not exactly “theirs,” but not wholly ours either. Now You See Me 2 may have attracted only mild interest here: little cultural chitchat, except maybe among magicians, and $65 million box office (less than Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN). But it garnered $266 million internationally. Nearly a hundred million of that came from China, perhaps partly owing to long stretches set in Macau and short stretches featuring Jay Chou Kit-lun. And the director was Asian-American Jon M. Chu.

Now Lionsgate announces a Now You See Me spinoff, a feature co-production with China that will use local stars. So who owns this franchise? “Us” or “them”? If it disappoints us and pleases them, how does that mean that movies are so over? Maybe other countries’ cultural conversations are pulsing with talk of the Four Horsemen (one of whom is a woman).

It’s long been obvious that other film industries create their own versions of Hollywood. Europe, India, and Hong Kong have done it for decades. Current Chinese hits borrow from “our” rom-coms, action pictures, and comedies. In Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s The Mermaid, you can watch a blockbuster premise coming unglued. It’s a mixture of sentiment, message, slapstick, and bad taste; Hollywood twisted up in Chow’s characteristic funhouse mirror.

This won’t stop. One of the most astonishing and puzzling facts of contemporary cinema gets almost no press, maybe because it contravenes the death-of-film narrative. Over the last ten years, there has been a huge rise in the number of feature films.

In 2001, the world produced about 3800 features annually. The number passed 4000 in 2002, passed 5000 in 2007, and passed 6000 in 2011. In 2014, IHS estimates, over 7300 feature films were made in the world. There are now fifteen countries that produce over 100 features a year. As a result, only 18% of the world’s features come from North America. The boom took place despite the rise of home video, cable, satellite, DVD, Blu-ray, VOD, and streaming. And it happened despite the fact that American blockbusters rule nearly every national market. This may be a bubble, or it may be genuine growth. In any case, we ought to investigate the reasons that a great many people around the world stubbornly persist in making two-hour films. They don’t appear to care if We sense a summer slump.

While I was preparing this entry, Kristin and I went to Our Little Sister, Kore-eda Hirokazu’s 2015 film about three sisters abandoned, first by the father, then by their mother, and raised by the moderately stern oldest sister. The plot follows what happens when the trio takes in their half-sister after her mother dies. This is a movie that’s bereft of villains and almost totally lacking in conflict. The sisters’ misjudgments and flaws cause them problems, and sometimes they quarrel, but mostly we see decent people trying to lead happy lives, and largely succeeding. Compared to Kore-eda’s debut, Maboroshi (1995), it’s pictorially rather conventional. (That damn sidling camera.) But its episodic, open-textured plot, its quiet depiction of changes across seasons and years, and its casually serene vision of family and community make it one of the most enjoyable and moving films I’ve seen this year.

Based on the graphic novel Umimachi Diary, the film participated in Japan’s “cultural conversation.” It’s certainly a mainstream commercial movie, of a sort that Japanese studios have turned out for decades. It won solid attention on the festival circuit too. It earned a 92% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, up there with Kubo and Hell or High Water. But such a reserved, sentimental film will never get the edgy buzz that our doomsayers want. Sentiment, after all, is anathema to our dominant mode of consuming pop culture, that of cool, ironic knowingness.

I don’t want to oversell Our Little Sister: Kore-eda is no Ozu. But this film and many others remind us that worthwhile films are still made, and released, and available outside the circus tent of Entertainment Weekly cover stories. (In this case, Americans’ thanks should go to Sony Pictures Classics, now celebrating its 25th anniversary.)

In short: Forget the zeitgeist; it likely doesn’t exist, apart from marketers’ dreams and journalists’ deadlines. Forget the cultural conversation; there’s not only one. Seek out the films that matter to you, and not “to us.” Stay classy!

Thanks to correspondents on two listserves, that of Communication Arts film folk and that of the Art House Convergence. A great many people made many suggestions, with the inevitable duplication, so thanking everyone by name would be protracted. But you know who you are.

My information on worldwide production and exhibition comes from issues of IHS Media & Technology Digest and Cinema Intelligence Report. Special thanks to David Hancock, Director of IHS Cinema division. Pamela McClintock’s “Summer Anxiety Despite Near-Record Numbers” in the 16 September Hollywood Reporter print edition contains the top-twenty film list I mention; that chart isn’t included in the online version.

On the summer 1966 US releases, see The Film Daily Yearbook of Motion Pictures 1967 (Film Daily, 1967), 144-168. I charted the year’s top-grossers from Susan Sackett, The Hollywood Reporter Book of Box Office Hits (Billboard, 1996).

My quotations from Pauline Kael come from her Bonnie and Clyde review reprinted in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1968), 47. My quotation from Vernon Young is the opening of his “The Verge and After: Film by 1966,” in On Film: Unpopular Essays on a Popular Art (Quadrangle, 1972), 273.

It’s probably irrelevant to mention that both Scorpio Rising and The Brig were released, in some sense, in summer 1966.

P. S. 18 September 2016: And see the practically real-time followup. Remember when blogs were like Twitter is now?

12,000 tickets are sold for premiere screenings of Baahubali (2015) in Hyderabad, India.

Reeling and dealing: Rescuing movies, by hook or by crook

DB here:

There have long been film collectors, and they’re central to film preservation. Some archives, notably the Cinémathèque Française and George Eastman House, were built on the private hoardings of passionate cinephiles. Filmmaking companies, both American and overseas, had little concern for saving their films until home video showed that there was perpetual life in their libraries. By then, many classics had been dumped, burned, or left to rot, and in many cases collectors came to the rescue.

In America, private collecting really took off after World War II. What happened afterward is too little known among cinephiles, but it represents an important part of film culture. A new book fills in a lot of the detail, and in a very entertaining way. It’s a big contribution to our knowledge of the afterlife of the movies.

16 + 35 = $$$$

In the late 1940s, 16mm versions of theatrical releases became widely available. For a while the studios contemplated replacing 3 5mm with 16 in regular theatres, but soon the narrow gauge emerged as the format for nontheatrical screenings. Schools, churches, and colleges got war surplus 16 projectors. The Museum of Modern Art circulated classics in the format, and for newer items programmers could turn to Audio-Brandon, Janus, and other distributors.

5mm with 16 in regular theatres, but soon the narrow gauge emerged as the format for nontheatrical screenings. Schools, churches, and colleges got war surplus 16 projectors. The Museum of Modern Art circulated classics in the format, and for newer items programmers could turn to Audio-Brandon, Janus, and other distributors.

Many of those firms dealt in foreign titles, which weren’t as attractive to most collectors—who were in love with Gollywood. For them, the floodgates had already opened when the studios licensed their pre-1948 product to television. The 1950s and 1960s were very unlike the multi-channel 24/7 TV environment of today. The networks didn’t fill the broadcast day, and many independent stations tried to support themselves apart from the nets. So everybody needed what we now call content. Our colleague Eric Hoyt has traced in detail how C & C Movietime and other entrepreneurs bought rights to classics and not-so-classics and packaged them in 16mm bundles for local TV stations. Those prints were shown throughout the day and night, interspersed with commercials cut in by staff like Barry C. Allen.

In the 1950s hundreds of copies of film classics were abroad in the land. But many of these TV prints wound up discarded and scavenged by guys (almost always guys) who wanted to show them at home. Aficionados started building their own libraries.

Collecting 35 was tougher, but it could be done. Older films were stored in labs and depots. They might wind up in Dumpsters or be smuggled out by enterprising employees. Of course showing 35 was more difficult, but it wasn’t impossible to get 35 projectors fairly cheap, and if the hobbyist was willing to make major home renovations, he (again, almost always a he) could set up a personal screening room. Some went with curtains, masking, auditorium seats, popcorn machines, and other amenities. The idea of “home theatres” for ordinary folks has its origin here.

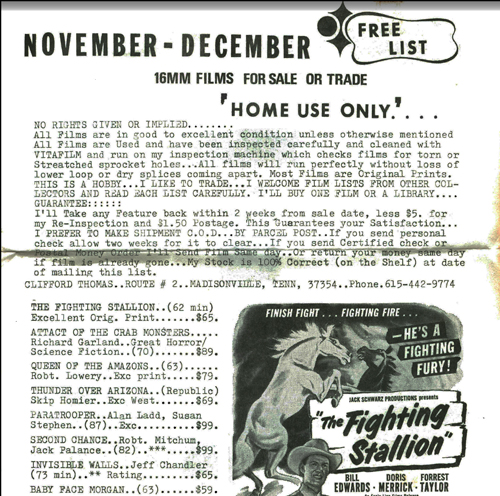

Acquiring 16mm was gray-market but ultimately not very criminal. Because of the First Sale Doctrine, a collector was not in violation if he bought a 16 print that had already been sold (to a TV station). If I buy the new Carl Hiaasen novel Razor Girl, I can sell my copy to you because someone sold it to me. What got 16mm dealers in real trouble was their zeal to copy prints. If they got access to a nice 35, they might make a 16 reduction; or if they had a decent 16, they might pull dupes. These were definitely illegal, as if I were to scan Razor Girl and sell you a pdf.

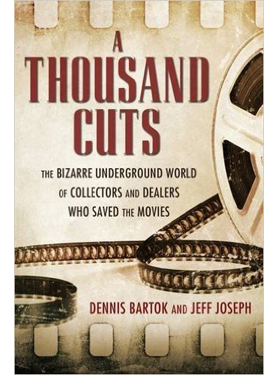

Mimeograph lists circulated by mail, but by the 1970s, collectors had their own periodicals, like Classic Film Collector and The Big Reel. To say that readers subscribed for the nostalgia pieces would be like saying you bought Playboy for the articles. The meat of the issues lay in the dealers’ lists, which might go on for pages. I well remember the rush to the phone after The Big Reel arrived each month. Once I called a Texas dealer who had advertised an untitled Japanese film. He was puzzled by its Irish name: The Life of O’Hara.

Mimeograph lists circulated by mail, but by the 1970s, collectors had their own periodicals, like Classic Film Collector and The Big Reel. To say that readers subscribed for the nostalgia pieces would be like saying you bought Playboy for the articles. The meat of the issues lay in the dealers’ lists, which might go on for pages. I well remember the rush to the phone after The Big Reel arrived each month. Once I called a Texas dealer who had advertised an untitled Japanese film. He was puzzled by its Irish name: The Life of O’Hara.

With some exceptions, 35 prints weren’t originally sold, only rented, and so possession of one suggested, to suspicious minds, big-time theft. Actually, most collectors’ prints had been junked, and you can argue that once something is tossed out, it’s the American Way to scavenge and recycle it.

Beyond the domestic collectors’ market, there was money to be made with 35 prints. American films didn’t circulate much in Cuba, South Africa, parts of Asia, and Eastern Europe, so there was an international demand for bootleg copies, and some dealers were happy to meet it. I lost out on a collection of Hong Kong films that was bought by an Indian dealer who intended to circulate them at home. I always think of that episode when I see the almost inevitable kung-fu fight in an Indian action movie.

The sale of 35 boomed because of another factor. With the rise of the blockbuster mentality in 1970s-1980s Hollywood, the nation was awash in theatrical prints. Then as now, a film might open on thousands of multiplex screens, play a few weeks, and be done. The studio would keep a few of those prints, but the rest would have to be disposed of. Salvage companies were contracted to destroy them, but—human nature being what it is—often some copies slipped out and into eager hands.

Films stored in laboratories or warehouses had a habit of disappearing as well, and prints shipped to theatres might be waylaid. I remember booking Blue Velvet and learning that the copy had disappeared in transit. The fact that prints were labeled with their titles printed in large letters probably didn’t help keep them safe. I was always startled to see the casual ways in which prints were handled. On Thursday midnights I’d leave a screening at one local theatre and see, neatly lined up on the sidewalk, shipping cases bearing the titles of films that had played there in recent weeks, waiting for a UPS pickup the next morning. After a theatrical run, exhibitors cared as little for prints as producers and distributors did.

Many collectors favored older titles, but others were as susceptible to blockbuster mania as general audiences. Star Wars, Jaws, The Godfather, and all the other top hits became as sought-after as Casablanca and Snow White. Collectors still boast of having multitrack, IB-Tech copies of 1970s and 1980s franchise pictures.

Enter the Feds

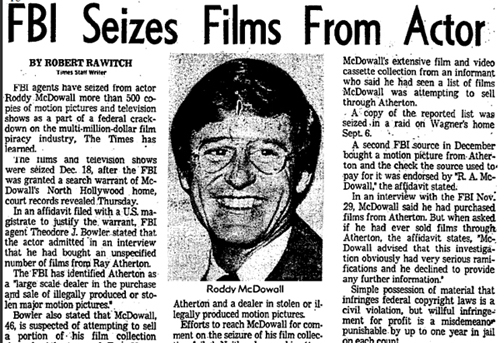

Los Angeles Times (17 January 1975), B1.

I’ve moved from describing the collectors’ market to describing the dealers’ market. That’s because they were almost one and the same. Collectors needed dealers to help find the rarities they yearned for; collectors started to deal to support their habit; and dealers, whether collectors or not, found that they could make money acquiring and selling movies. Demand and supply, in solid capitalist fashion, created an underworld traffic in prints.

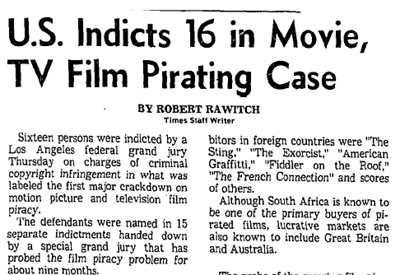

The studios didn’t take this lying down. With the aid of the FBI, they pursued collectors, pressuring them to snitch on their suppliers and fellow addicts. Former child star Roddy McDowall, an avid collector, was the most visible target of these maneuvers. I well remember the chill that passed through the collector community at the news of the Feds’ raid on his house, which turned up hundreds of prints and videos. McDowall, who could probably have won a legal case, gave up many of his contacts. Charges against him were dismissed, but the U.S. Attorney pursuing the case warned that the activities of film collectors (said to number 65,000) “could constitute serious violations of both state and federal law.”

Most collectors flew under the radar, though. Although McDowall’s collection was mostly 16mm, the studios turned a blind eye to 16mm collectors. Famously, William K. Everson helped studios uncover lost films (e.g., obscure Fords and Stroheims) and as payment received 16mm copies of his discoveries. Collectors like Bill, who accumulated several thousand prints, shared their libraries with archives and film schools; at NYU, Bill taught from his collection for many years.

Home video didn’t destroy this underworld right away. The first video systems were of such poor quality that they couldn’t compete with 16mm projection, let alone 35. However, as formats improved in the 1990s, more and more collectors turned to video. Why thread up a battered copy of an MGM musical when a pretty nice DVD could just be popped into your player? With the arrival of Blu-ray, which can look very impressive projected in theatrical conditions, 35 began to be seen as more and more a retro hobby. And your average hobbyist was discovering that he (still almost certainly a he) was aging. Or dying.

The studios mostly lost interest in film-based piracy, once video presented a threat on a much bigger scale. Duplicating VHS and laserdisc, always imperfect, was followed by the cloning of perfect copies of DVDs. Now, of course, the main arena is the Net, where film piracy via BitTorrent has exploded to a level the old-timers couldn’t imagine. Back in the 60s, there were very few film collectors. Now, thanks to digital convergence and massive hard drives, everybody is a film collector—not only he’s.

Boom and busts

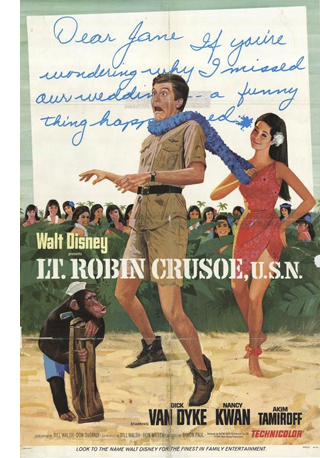

This is the world chronicled, with affection, humor, gossipy detail, and a pang of melancholy, in Dennis Bartok and Jeff Joseph’s A Thousand Cuts. Dennis has been head of programming for the American Cinematheque, and he currently heads the distribution company Cinelicious Pics. Jeff was one of the top film dealers in the country; at its peak, his company SabuCat sold about 1,000 prints per month. In the wake of the McDowall bust, Jeff became the only film dealer to serve time for selling prints. Jeff is now a distinguished archivist, conserving 3-D prints and, most recently, rare Laurel and Hardy movies.

The book lives up to its subtitle: The Bizarre Underground World of Collectors and Dealers Who Saved the Movies. Through interviews, documents, and vast knowledge of the world of film dealing, Bartok and Joseph have given us an invaluable survey of a wondrous land. It’s as gripping, and sometimes as hallucinatory, as any Forties B noir.

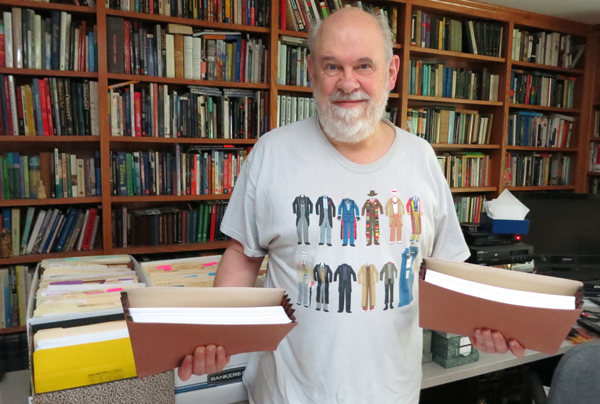

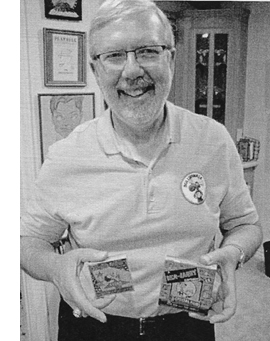

Start with the cast of characters. Hugh Hefner, it turns out, was a huge collector, and not just of erotica. Probably today’s most visible collectors are Robert Osborne, of Turner Classic Movies, and the genial Leonard Maltin (right), who has lived in many worlds—fandom, mainstream publishing (thorough books surveying aspects of film history), and mass media (TCM, Entertainment Tonight, etc.). His obsession: shorts and cartoons. Men with an appetite for features include director Joe Dante and producer Jon Davison, whose collections continue to grow.

Start with the cast of characters. Hugh Hefner, it turns out, was a huge collector, and not just of erotica. Probably today’s most visible collectors are Robert Osborne, of Turner Classic Movies, and the genial Leonard Maltin (right), who has lived in many worlds—fandom, mainstream publishing (thorough books surveying aspects of film history), and mass media (TCM, Entertainment Tonight, etc.). His obsession: shorts and cartoons. Men with an appetite for features include director Joe Dante and producer Jon Davison, whose collections continue to grow.

Once we leave behind the celebrities, things take a more exotic turn. There’s Evan H. Foreman, the first collector targeted by the studios, a tough customer who fought for the right to sell prints and was called to testify before a Senate committee. There’s Ken Kramer, proprietor of The Clip Joint, a Burbank archive and screening facility decorated with posters and Christmas lights. There’s Tony Turano, who claimed for years that he was the baby in the bulrushes in The Ten Commandments. Tony kept his apartment heavily curtained, the better to preserve Claudette Colbert’s headdress and robe from Cleopatra (1934). Paul Rayton, projectionist extraordinaire, stores the cans for his rare Oklahoma! print in the back seat of his car. Not the film–it went vinegar long ago. Just the cans.

There’s Al Beardsley, uniformly considered untrustworthy, perhaps because he simply picked up a 70mm print of Lawrence of Arabia posing as a delivery courier and immediately sold it to a collector. Beardsley gave up film dealing for sports memorabilia, and became a participant in the O. J. Simpson throwdown in Vegas. As Beardsley recalls his encounter with one Thomas Riccio, who had set up the O. J. meet: “I had a drink and, I believe, a hamburger that Riccio paid for. He feeds you before he screws you.” O. J. was more direct: “Motherfucker, you think you can steal my shit and sell it?” Yes, firearms were involved.

This is as wild and crazy as any nerd culture can be. Like collectors of comic books and LPs, film mavens are clannish and wily, generous and secretive, boastful and yet somewhat innocent. These guys can’t be considered Geek Chic; they retain an unselfconscious love for what moved them in their youth. They live in the Adolescent Window, as we all do, but they don’t pretend to have become hip. And they run risks that other collectors don’t. A book or record collector runs no risk of arrest. But should a film collector offer a rarity to an archive? Will the studio claim it and bury it? Will the law get involved? Paranoia strikes deep, and justifiably.

Some of the tales are painfully funny, some just painful. This is the sort of book that contains sentences like:

The two were briefly partners as film dealers in the early 1970s, until Ken’s then-wife Lauren left him to marry Jeff, shortly after they were discovered having an affair at the 3rd Annual Witchcraft and Sorcery Convention.

Turano, wheelchair bound, had a habit of bursting into showtunes at the top of his voice. Tom Dunnahoo, of Thunderbird films, “routinely passed out on the floor of his film lab drunk on Drambuie.” A dealer takes pride in the fact that at his trial, the expert on the stand couldn’t tell his dupe of Paper Moon from the original. Another bit of dialogue:

“You remember I had a beet-red print of Giant? Well, Louie Federici ran it and borrowed a beautiful IB print of Giant. Afterward he sent it back to Warners, and you know what they got? A beet red print,” he says, face lighting up.

“You swapped it out?” Jeff asks.

“I did. And later I traded it to you for Singin’ in the Rain. How about that, huh?”

Nearly every page of my copy boasts my penciled ! in the margin.

Saving the movies

Jeff Joseph and Dennis Bartok, Cinecon 2016.

The book stresses that collectors functioned as preservationists. Just as in the early days of archives, they have saved films major and minor from destruction. Just last week, we learned that a collection of 9.5mm has added more footage to a partially surviving Ozu film, A Straightforward Boy. Famously, missing King Kong footage was discovered by a collector. . . and given, not sold, back to the studio. Tony Turano found a missing Fred Astaire number from Second Chorus in Hermes Pan’s closet. Jeff Joseph preserved color behind-the-scenes footage of Animal Crackers and found remarkable home-movie Kodachrome footage of Hitchcock, Bergman, and Grant out for a walk during the shooting of Notorious (surmounting today’s entry). Mike Hyatt has devoted his life to cleaning up The Day of the Triffids. Using a jeweler’s loupe and a needle, across many years, he flicked over 20,000 bits of dirt out of the camera negative.

Every collector I’ve known has welcomed sincere interest in their holdings. In pre-video days, Bill Everson (right), unbelievably, loaned prints to undergrads for their papers. Kristin and I spent many nights at friends’ homes screening rare silents and unusual items, like a full-frame print of North by Northwest that showed the edges of the Mount Rushmore backdrop. Nearly every chapter of A Thousand Cuts recalls nights when the collectors would screen their rarities. Cutthroat they might be in dealing, they were often eager to share their treasures with those who’d appreciate them.

Every collector I’ve known has welcomed sincere interest in their holdings. In pre-video days, Bill Everson (right), unbelievably, loaned prints to undergrads for their papers. Kristin and I spent many nights at friends’ homes screening rare silents and unusual items, like a full-frame print of North by Northwest that showed the edges of the Mount Rushmore backdrop. Nearly every chapter of A Thousand Cuts recalls nights when the collectors would screen their rarities. Cutthroat they might be in dealing, they were often eager to share their treasures with those who’d appreciate them.

Most of the stories in the book come from the West Coast, as you’d expect. Other regions have their own lore and characters. The East Coast was a lively scene, centering on Manhattan’s Theodore Huff Film Society (duly noted in A Thousand Cuts) and Bill Everson’s screenings at the New School and elsewhere. Scorsese is, of course, a famous collector. Until this last year hard-core fans of old films gathered at Syracuse’s fine Cinefest. The Midwest had its own center of film trade, Festival Films in Minneapolis, now a source of public-domain items. The screening-and-dealing gathering Cinevent, in Columbus, Ohio, is entering its 49th year.

There were colorful personalities hereabouts too, including a Milwaukee collector with a stupendous array of original Hitchcocks from the 1950s. Another Wisconsin collector, Al Dettlaff, discovered and jealously guarded Edison’s 1910 version of Frankenstein. I met a collector in remote Minnesota who had converted his garage for 35mm screening both indoors and outdoors. He could aim his projectors to shoot out onto the back yard for neighborhood shows (a popular pastime for collectors). During the snowbound winters, he could swivel the machines to shoot through the kitchen to the living room. I asked how his wife felt about sawing holes in the walls. He said: “She’s fine with it. She knows I can get a new wife a hell of a lot easier than an IB Tech of Bambi.”

Dennis and Jeff are to be thanked for recording precious information about a phase of American film culture that has been neglected. They’re continuing the effort with a clip show on 23 September at the American Cinematheque’s Egyptian Theatre. It will include many items mentioned here, as well as a Bela Lugosi interview from 1931.

The collecting adventure is not quite over. The book profiles passionate younger aficionados, some of whom keep the energy going online. Still, as someone who has relinquished his passion for owning film on film and is happy that archives are taking over the task, I’m afraid it’s evident that the curtain is coming down. Without collectors, who will scavenge all the films not likely to be transferred to digital formats? The book ends with a list of six interviewees who died during writing and publication. And in the podcast below, Jeff glumly notes that studios are still junking prints.

Thanks to Jeff Joseph for illustrations. The Len Maltin picture is by Dennis Bartok. For a fascinating podcast that gives the authors a chance to expand on many aspects of A Thousand Cuts, check The Projection Booth. There’s a shorter streaming interview at KPCC radio.

Typical collector story: How did William K. Everson acquire his K? He told us that the first movie he remembered seeing was by William K. Howard, so Bill borrowed the middle initial. Another: We did our bit. After seeing an ad in The Big Reel for a hand-tinted Méliès print, we alerted Paolo Cherchi Usai, then at Eastman House. It turned out to be one of the lost Méliès titles.

Thanks to Haden Guest for tipping me to the Ozu rediscovery. I talk about how piracy created a classic here. For more on 16mm collecting and showing, go here and here. In this entry we cover Joe Dante’s remarkable visit to Madison and his presentation of The Movie Orgy, one result of his insatiable collecting appetites.

P.S. 14 September 2016: I should have mentioned another collector committed to preserving 3D films. Since 1980 Bob Furmanek has been building a large 3D archive, a project that is still ongoing. The history of his work is traced on his site.

P.S. 15 September 2016: Thanks to Christoph Michel for correcting a howler that out of shame I shall not name.

Animal Crackers, Multicolor on-set record (1930). Courtesy Jeff Joseph.

Oof! Out!

I Remember Mama (1948).

DB here:

Jim Naremore calls 1940s American studio cinema “the beating heart of Hollywood.” I think he’s right. For about five years I’ve been working on a book taking EKGs of that beating heart. The book tries to understand some factors that made Forties Hollywood so dynamic and continually captivating.

Doing this called my attention to so many things: the fresh subject matter, the variations in genres, the stylistic experiments, the superb performances, the quality of line-by-line writing. But I focused on something that’s still pretty big: new, or newly revived, storytelling methods. Those methods made that period exciting–not just in film noir, where we tend to think that narrative got pretty wild, but also in melodramas, rom-coms, musicals, and the rest.

It’s the only study I know of how narrative techniques emerged and developed in a single era. No wonder it took five years. I watched over 600 films. I trawled through books and trade papers for hints about what the producers, directors, and writers thought they were doing. And because a lot of techniques weren’t unique to film (e.g., flashbacks, first-person voice-over, etc.), I wound up reading forgotten plays and neglected novels, while listening to hours of old-time radio.

The project started when I was asked to do a series of lectures, “Dark Passages,” for Belgium’s Summer Film College in 2011. Just before that, I tried out some ideas in some spring blog entries. Things crystallized in 2013, when I firmed the project up. In this entry, I promised, falsely, that the book would be short.

Since then, I’ve been immersed in fun, except for the Red Skelton movies. I loved having Mercury Theatre playing in my car during drive-time, and digging out 1930s and 1940s books from the oldest section of our university library.

I think the book says some new things about films of the period, and about the development of American popular entertainment more generally. For one thing, I think I have a better understanding of how High Modernist techniques (out of Joyce, Woolf, etc.) made their way into mass art. (Not directly, I’m convinced.) For another, I have a new respect for those filmmakers who tried something daring, even if–see my last post on The Chase (1946)–they somewhat botched it. And it develops some ideas I floated in The Way Hollywood Tells It: ideas about how modern filmmakers like Tarantino and Nolan are continuing a Forties tradition of somewhat experimental narrative.

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling went off to the publisher this afternoon. Said publisher is the University of Chicago Press, who did a fine job with our Minding Movies and my recent little book The Rhapsodes, to which this is sort of a bigger, thuggier brother.

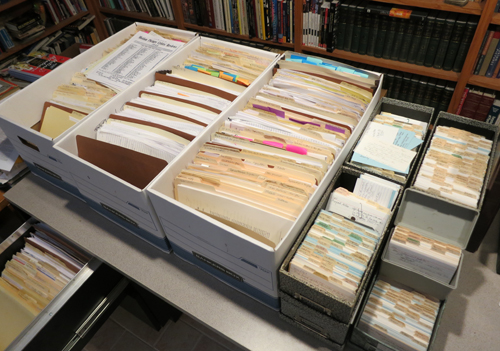

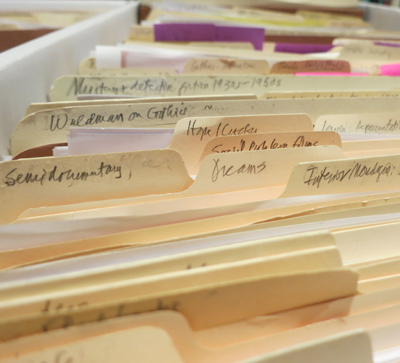

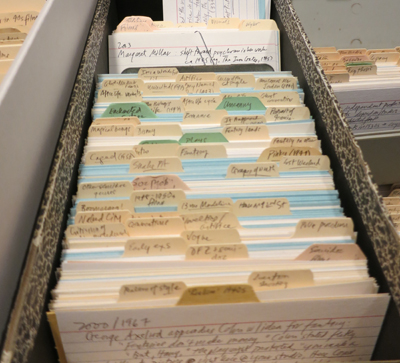

In the meantime, just to give you an idea of how one writer makes a book, I append some images from the workbench, before I pack up the paperwork. Here are the file folders and note cards I worked from. Hard to get those long note-card boxes nowadays; I needed 8 1/2 for this project.

Yes, I’m still a pen-and-paper nerd. All that’s changed since my 60s student years is the worsening of my handwriting.

Like you, I have hundreds of digital files too.

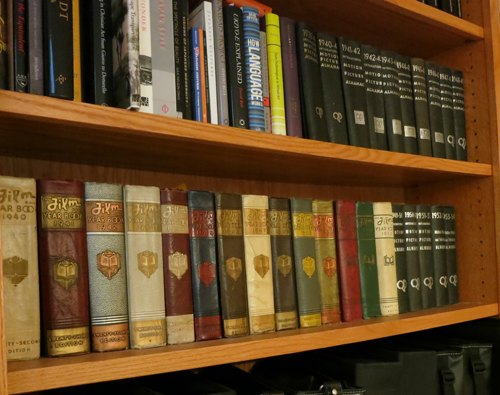

I was reliant on my old friends, The Motion Picture Almanac and The Film Daily Yearbook.

I amassed many albums of DVDs, as you’d expect–thanks chiefly to Turner Classic Movies.

Of course there are scores of books about films and figures of the period. I depended a lot on two key surveys: Douglas Gomery’s Hollywood Studio System (both editions) and Tom Schatz’s Boom and Bust: American Cinema of the 1940s. I didn’t rely much on all those books of a reflectionist, Zeitgeisty flavor–for reasons I’ve indicated here as well as in the book.

Reinventing Hollywood should be out this time next year. It should run to around 550 pages, with 180 illustrations. In addition, I’ll be putting up a dozen or so clips online to supplement some of my analyses. Hereabouts, from time to time I’ll preview arguments in the book.

I want to thank my editor, Rodney Powell, and his colleagues at the University of Chicago for supporting the book. I also owe a debt to Jim Naremore, Jeff Smith, and Malcolm Turvey for their close reading of the thing in draft form, and of course to Kristin for help in matters big and small. The couple dozen of friends and colleagues who helped me, too many to list here, are gratefully acknowledged in the text.

To give you a sense of what the book is up to, I’ve gathered most of my Forties blog entries into a separate category. Some of these are grist for the book, and some, like the ones on The Magnificent Ambersons and on The Chase, expand the book’s analysis.

In all it reminds me of what the Duke of Gloucester said to Gibbon: ““Another damn’d thick, square book! Always, scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh! Mr. Gibbon?” I’ve used this before, but after writing or rewriting seven books since I retired in 2004, it seems even more grimly appropriate. The reader is warned.

Photo by Kristin Thompson.

In pursuit of THE CHASE

The Chase (1946).

DB here:

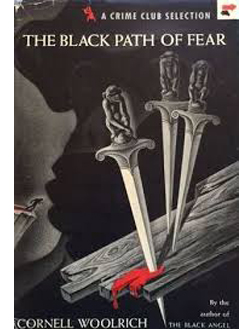

While writing my book on Forties Hollywood, I often felt that every movie I talked about was based on a bestseller, a Broadway play, or something by Cornell Woolrich. Many of the best, or at least strangest, films of the era come from his haunted imagination.

T he Chase (1946), long a cult film maudit, is for some aficionados the ultimate noir. It manages to be even more peculiar than its source novel, Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear (1944). Although I began reading Woolrich as a teenager, I didn’t catch up with the film until the 2000s, in a so-so DVD. It has come to occupy a minor place of honor in the book (due out next fall, thanks for asking).

he Chase (1946), long a cult film maudit, is for some aficionados the ultimate noir. It manages to be even more peculiar than its source novel, Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear (1944). Although I began reading Woolrich as a teenager, I didn’t catch up with the film until the 2000s, in a so-so DVD. It has come to occupy a minor place of honor in the book (due out next fall, thanks for asking).

Kino Lorber has recently released The Chase in a nicely cleaned-up DVD/Blu-ray edition. So all hail UCLA’s efforts restoring this neglected item, as well as its rescue of other worthy titles: Renoir’s The Southerner (1945, also from Kino Lorber), Too Late for Tears (1949), and Woman on the Run (1950), the last two from the estimable Flicker Alley. Kino Lorber has decorated the Chase release with commentary by Guy Maddin and recordings of two radio shows based on the Woolrich novel. (A pity we don’t have the Hedda Hopper radio show promoting the film, but maybe that’s lost.)

My book features The Chase because it poses with extreme prejudice the question of how far narrative innovation could go in the 1940s. Sometimes, as I’ve argued with The Great Moment and All about Eve, filmmakers go too far and get pulled back. But then readjustments necessary in postproduction may create twitches of novelty too. The Chase is another example of innovation by accident.

In the book, I mostly analyze the film. But I’ve also done a little digging into its production and promotion, as a way of explaining some of its captivating oddities. I came up with some information I haven’t seen discussed anywhere, so I thought I’d pass it along in a blog entry.

I haven’t located any scripts, alas, but our archive at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research holds other intriguing documents, including correspondence, a typescript synopsis, and a gorgeous presskit. Elsewhere I came across a document that gives clues about what the script and, at one stage, the film were like. There are reasons to think that an early version of the film was even stranger than the finished movie.

There must be spoilers, for both The Chase and The Woman in the Window (1944). Oddly enough, as we’ll see, contemporary reviewers of these movies didn’t worry about spoilers, so maybe I shouldn’t either.

Die in Havana, wake up in Miami

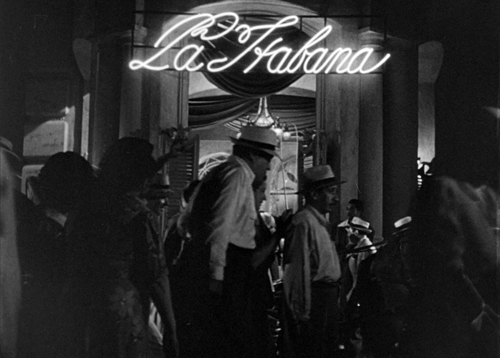

The Black Path of Fear begins in a fraught situation. Bill Scott enters a Havana club with an American woman. As they kiss, she is suddenly stabbed to death, and he’s the prime suspect. He escapes from police questioning and takes refuge in the tenement apartment of another woman, nicknamed Midnight. Scott recounts his backstory in a brief flashback, and then he sets out to find the people who have killed his woman and framed him. His effort takes him into the opium racket run by Eddie Roman from Miami. The bulk of the action takes place in Havana, with the flashback and a penultimate episode set in Miami.

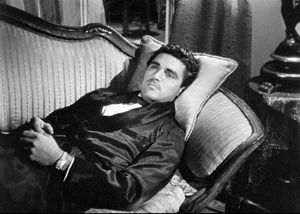

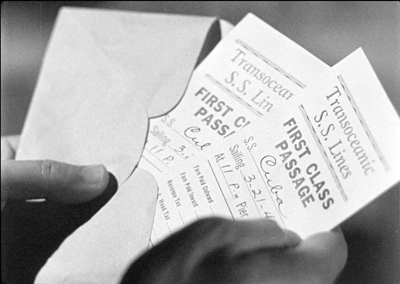

The Chase shifts the book’s flashback material to its chronological place. The film begins with navy veteran Chuck Scott down on his luck. He finds a wallet belonging to crooked businessman Eddie Roman, returns it, and for his honesty is rewarded with the job of a chauffeur. He meets Eddie’s wife Lorna, and soon they are plotting to run away to Havana.

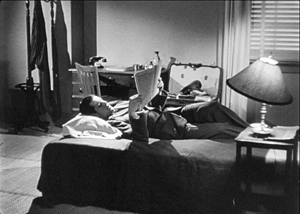

That’s when things get strange. On the night of the couple’s planned escape, Scott stretches out to read a newspaper. Fade out and up to Eddie, also stretched out, listening to a phonograph record–first in extreme long shot, then in mid-shot.

Eddie’s assistant Gino comes to Scott’s room and finds him gone. He reports to Eddie, showing the telltale travel folder.

As the recorded music continues, we are taken to a ship, where in a stateroom Scott is playing the same tune on a piano. Lorna is with him and they are evidently on their way to freedom.

Once the lovers are in Havana, The Chase follows the original novel, up to a point. Lorna is stabbed to death in the bar, Scott becomes the main suspect, and he flees the police by hiding in Midnight’s apartment. Soon Scott discovers that Gino is in Havana. He has arranged Lorna’s murder and the frame-up of Scott.

But now comes an astonishing twist, not in the novel. Gino finds Chuck hiding behind a curtain, shoots him, and dumps his body down a trap door. The body lies lifeless on the stair.

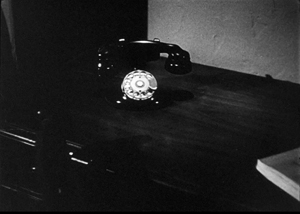

This is plotting in extremis. An hour into the film, both heroine and hero have evidently been killed and the unsavory characters have won. How to get out of this impasse? A telephone in the cellar rings. Cut to a ringing telephone on a desk, and track back. Chuck Scott is waking up, still on his bed with his newspaper.

He has dreamed the entire thirty-minute escape to Cuba, and we weren’t told he had fallen asleep.

This is the sort of twist modern filmmakers don’t advertise in advance, and indeed online accounts of the Kino Lorber disc, such as the shrewd review by Glenn Erickson, have been admirably discreet about it. Yet contemporary reviews openly revealed the device. Six out of seven trade-paper reviews I’ve found announce the dream twist. Daily Variety claimed that this “wild and disordered narrative” consumes “more than half the picture” (no) and “throws audience for a loss” (yes). Motion Picture Herald was less condemnatory—“the whole tangle untangles in a satisfactory manner”—but somehow found that Scott “has been dreaming a dream inside of a dream.”

Critics in the general press were likewise unafraid of spoilers. Life was a bit coy: “Its highly improbable plot has the eerie sensation of a bad dream.” The New York Times was more explicit: “All the foregoing horrors, however, are only a nightmare of Cummings’ ailing brain.” Of the violence, the Los Angeles Times noted, “Most. . . occurs in a dream sequence, which proves puzzling at first….” So perhaps some audiences, primed by reviews, were actually waiting for the twist. The film’s presskit does include suggestions for dream stunts exhibitors might try.

In any case, the dream has taken its toll on Chuck. Now he has amnesia, which spread among 40s movie heroes like a plague. Forgetting his promise to help Lorna escape, forgetting even how he got the chauffeur job with Eddie, he returns to his navy doctor for help. “It’s happened again,” Scott tells him. Dr. Davidson says he has “anxiety neurosis,” dismisses the Havana material as “dream-stuff,” and reassures him that he’s getting better. But from the spectator’s standpoint, the entire plot is put on hold.

The climax carries coincidence to new heights. Dr. Davidson takes Scott to a restaurant for a drink. Pieces of Chuck’s memory return, chiefly the name Lorna. At that moment Eddie and Gino stroll into the restaurant, having locked up Lorna at home. As Davidson chats with Eddie, Chuck finds the tickets to Havana in his pocket and remembers more. Rushing to Eddie’s mansion, he frees Lorna and takes her to the ship. Eddie learns of their plan and races to get to the pier, but en route his car is struck by a train.

Unlike Woolrich’s novel, The Chase takes place almost wholly in Miami, with the Havana dream as an interlude. The epilogue returns to the Havana nightclub and Chuck and Lorna in a carriage at the curb. As they embrace, Chuck says, “We’ll be together forever.”

There doesn’t seem to be any beginning

The Chase, released 22 November 1946, followed a series of and-then-I-woke-up pictures: The Woman in the Window (1944), The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945), and Strange Impersonation (March 1946). All of these thrillers depend on a double bluff. They seamlessly move from waking life to a dream scenario without tipping us off. They return to real life in a symmetrical fashion, while letting us observe how we were misled.

Hooks are very helpful here. For example, in The Woman in the Window, Professor Wanley asks a club servant to remind him when it’s 10:30. He settles down to read. Dissolve to the clock chiming 10:30.

Wanley is still reading when the servant’s voice from offscreen tells him the time. The camera pulls back as the servant enters the frame.

The transition is imperceptible. At the climax of the dream, when Wanley has sought to commit suicide with an overdose of sleeping powder, we get a parallel situation: He’s seated in a chair at home, and the camera tracks in. He seems to die, as the lighting changes.

But the servant’s hand comes in to shake him, he awakes, and we hear the club clock chiming 10:30. The camera tracks back, and the glass in Wanley’s hand in the dream has become the sherry glass he held in the framing scene.

Like its predecessors, The Chase doesn’t signal its dream transition. No whirling superimpositions lead into it, no outlandish compositions announce that we’re in the middle of it. (For comparison, see Stranger on the Third Floor, 1940.) As in The Woman in the Window, the shift is cunningly concealed. Here offscreen music on Eddie Roman’s phonograph is continued as an auditory hook into the start of the dream.

In retrospect, we might argue that the Havana episode hints at its subjective status. Chuck yawns slightly as he’s reading his newspaper, though I don’t think most viewers take that as a dream cue. The concerto music, issuing from a phonograph in Eddie’s living room, is, implausibly, picked up by Scott, who plays the tune on board the ship. The light falling on Lorna and Scott in their cabin is markedly unrealistic, with a shadow dropping and rising on the porthole.

Scott tells Lorna to “Forget time,” and the song to which the couple dance in the club contains the line, “Like the stars in a dream song.” And when Dr. Davidson asks how it all began, Scott replies: “There doesn’t seem to be any beginning”—as if acknowledging the surreptitious segue into his imaginings. The Chase wouldn’t be the first 1940s film to flaunt its own artifice.

The Chase revises the dream schema in a couple of intriguing ways. For one thing, The Woman in the Window and Strange Impersonation make the dream the bulk of the film; the lead-in and lead-out are fairly perfunctory. Many other films make the dream a brief one, enclosed within long stretches of real-life action. The Chase gives us something midway between, a thirty-minute dream that functions as a block almost exactly equal to the chunk of real-world action that precedes it. We have to trace our steps backward to an earlier point of departure and then reckon how new action connects to it. Something similar happens with Uncle Harry, but there the dream comes so late as to supply the film’s climax.

Moreover, in the other films, the dream doesn’t actually alter the real-world situation that gave birth to it. Here, though, the dream has a causal function: It triggers the recurrence of Chuck’s amnesia.

The Chase goes a little farther than its predecessors in another way, The other films in the cycle keep the visual narration attached to the dreamer before and after the transition; that is, the dream’s first scene shows us the dreamer continuing to act. Both Woman in the Window transitions keep us fastened on Wanley. But the first scenes in Scott’s dream feature not Scott but Eddie and Gino. We accept this shift of attachment partly because from the start the film’s narration has been fairly unrestricted, crosscutting between Scott and Eddie. Early in the dream, this departure from Scott’s range of knowledge seems to confirm the objectivity of what follows.

Scott, it turns out, can dream what the bad guys are doing, and because of this we can get a moment of even sneakier duplicity. Within the dream, Gino finds Chuck gone. The beer bottle and discarded newspaper help reaffirm the reality of the scene because an earlier scene of Scott rising included the same props: the beer bottle on the nightstand, and a newspaper in Chuck’s lap.

With the turn to the amnesia device, things become no less dislocated. After Scott visits Dr. Davidson, he becomes surprisingly telepathic. When Eddie learns that Lorna wants to leave, he beats her and locks her in. Dissolve from her sobbing on the floor to Chuck at the bar, staring into space and remembering her name.

Immediately after we’ve seen Eddie’s car smashed by the train, Scott is waiting with Lorna in a stateroom that recalls the dream flight. He’s seized by a calm confidence, as if he intuited their salvation. “It doesn’t matter now.” From that we segue to the two kissing in the carriage outside the Havana club.

For all its attractiveness, Scott’s Cuban adventure doesn’t resolve the main plot. It postpones the Miami action by motivating his new bout of amnesia. Once Chuck loses his memory and flees Eddie’s house, the couple’s planned escape is scotched and the film has to start over by introducing a new character, the therapist Dr. Davidson, and relying on massive coincidence to bring Eddie and Gino back into the action. Perhaps this is why trade critics complained that the last stretch of the film was clumsy.

The case of the missing flashback

So far, so weird. But I think that an earlier state of The Chase was even weirder.

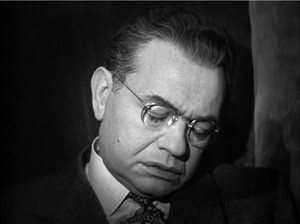

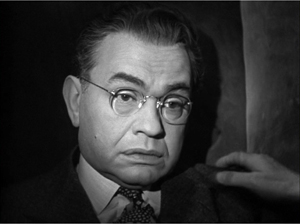

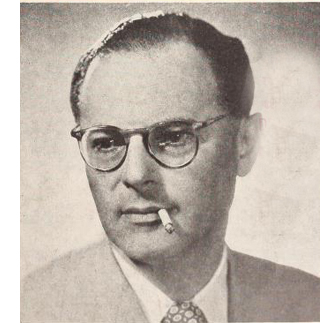

First, some background. Judging by the press coverage, it seems that the figure of authority on the film was the producer Seymour Nebenzal (below). He was a venerable figure, having produced many German classics—M (1931), The Threepenny Opera (1931), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933)—before fleeing the Nazis. He spent some years in France, producing among other films Mayerling (1936) and Ophuls’ Roman de Werther (1938). Emigrating to the US, he continued to work as an independent producer, with such films as We Who Are Young (1942), Prisoner of Japan (1942), and the Sirk films Hitler’s Madman (1943) and Summer Storm (1944).

Screenwriter Philip Yordan had bought the rights to Maritta Wolff’s 1941 novel Whistle Stop, prepared a screen adaptation, and sold the whole package to Nebenzal. Nebenzal had just reconstituted his Weimar company Nero Film, and Whistle Stop (January 1946) was its first release. Yordan applied the same packaging strategy to The Black Path of Fear. He bought the rights to Woolrich’s novel, then sold them and his adaptation to Nero. Director Arthur Ripley became involved after halting work on his adaptation of Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel.

Yordan was said to have had a financial interest in the film, and apparently Nebenzal promised him the credit “Philip Yordan’s The Chase,” which didn’t come to pass. Most of the publicity spotlighted Nebenzal, who was credited with many of the creative decisions.

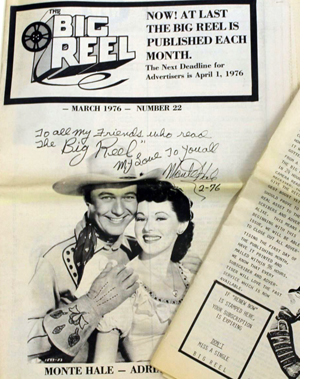

The Chase was not a low-budget project. It was promoted and distributed as an A picture. Boxoffice, the exhibitors’ trade paper, called it a “grade-A gripper, aimed at class houses.” The presskit reveals a tie-in with the Arthur Murray dance studios, which would teach patrons a new step, “The Chase.” (See at very bottom.) At worst the picture might function as a “nervous A” because of the relatively second-tier status of its stars (though Robert Cummings had profit participation in the project).

The production budget, according to an October 1947 financial statement in the WCFTR Collection, was $898,300.60. That doesn’t include debt service of about $40,000. In public statements, Nebenzal claimed that he boosted the film’s budget to $1.2 million. In all, these figures are in line with a mid-range A picture for the period; the average negative cost for all feature films in 1946 was $665,863 (in an era with a lot of B’s at $300,000 or less).

As befits its budget, The Chase contains solid miniature work and big sets, like Eddie Roman’s mansion and the Habana Club. Reviews praised its high production values, achieved by shooting at the Goldwyn studio. There are a couple of impressive crane shots, and Daily Variety reported that three camera booms were used on some scenes. There was time for finicky reshoots during and after principal photography.

In the course of production, Nebenzal issued a stream of press releases. The most important for our purposes appeared in Daily Variety of 16 September 1946.

Producer Seymour Nebenzel, believing market is glutted with flashback pictures, has ordered film editor Edward Marin to eliminate flashback sequence in Robert Cummings starrer, “The Chase.” Script was written so action could start from scratch, instead of starting with chase and then flashing back to start of action, as is done in the Cornell Woolrich novel.

Huh? What flashback?

When I found this item some years ago, I thought: Of course. The novel has a flashback to Miami, and the film moved it up to be part of the opening Setup. But then I realized: The flashback to Miami would have made sense only if the bulk of the film’s action were in Havana. But the film as we have it curtails the novel’s Havana action—most drastically, by killing off the protagonist. Was it possible there was a whole alternative film in which Scott survived and tracked down Roman’s opium-smuggling ring, as in the book? Was all that footage shot but jettisoned?

More likely, the bulk of the action was always going to take place in Miami. (The chase is a relatively small part of The Chase.) For one thing, Jack Holt was signed to play Davidson in early July. Davidson is the catalyst for the action leading to the climax, so once Holt was aboard, the final stretch of the film seems locked to Miami.

So maybe Nebenzal’s remark about taking the “flashback” out was just loose talk. He did display a general pattern of shilly-shallying. He publicly pondered, for instance, whether Lorna should live or die. He claimed to have requested two versions of the script: one in which Lorna remains dead at the end (as in the novel) and one in which she isn’t really dead (to be managed somehow). He said he’d leave it to preview audiences to decide.

This seemed to me a big tease. Nebenzal originally wanted Joan Leslie for the part and pursued her intently before discovering that she was unobtainable. Michèle Morgan, though a minor figure in the States, was a star in France; she won an acting prize at Cannes shortly before The Chase was released. By the fall Nebenzal sought to sign her to a longer-term contract. Keeping Lorna alive for more screen time, as happens in the film’s final Miami section, would be a good buildup for Morgan. In an April press release, Nebenzal had already seemed inclined toward letting Lorna live.

“After all,” he reasoned, “people want to be relieved of their daily troubles when they go to the movies. They don’t want to see their favorite actor or actress killed off.”

By September, Lorna definitely survived. Another press release:

Seymour Nebenzal shot 3 endings for “The Chase,” showing Robert Cummings and Michèle Morgan fleeing by land and sea. One ending had them scramming aboard ship, another on a train, the third on a bus. So far the bus flight is favored.

The shipboard option was chosen, obviously, but the mention of alternative escape vehicles entails that by early September, Lorna was intended to survive one way or another.

All this on-again, off-again made me disregard the item about “eliminating the flashback” as guff or misreporting. That was a mistake.

The film beneath the film

Then as now, one way to promote a new Hollywood release was to publish a novelization: not the original book that the film was based on, but a new literary text derived from the film. As I write this, Alexander Freed’s novelization of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story is available for preorder. Then as now, the novelization would be timed to arrive when the film was released.

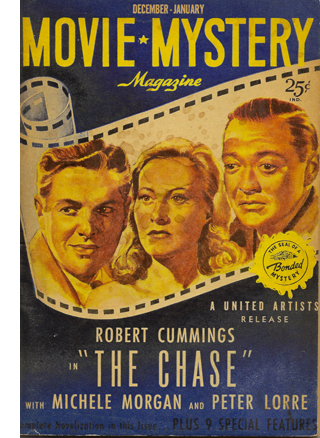

In late June Nebenzal told United Artists officials that he had arranged for a “fictionization” of The Chase, to be published in Movie Mystery Magazine. That periodical’s inaugural issue, dated December-January 1946, did appear on newsstands in November, during the film’s release.

In late June Nebenzal told United Artists officials that he had arranged for a “fictionization” of The Chase, to be published in Movie Mystery Magazine. That periodical’s inaugural issue, dated December-January 1946, did appear on newsstands in November, during the film’s release.

Novelizations, then as now, were typically prepared not from the finished film but from a script or treatment. And indeed Nebenzal indicated in his letter that he would be sending the magazine a copy of the script. It seems likely, then, that the version of the film “fictionized” in MMM reflects the state of the script in the summer of 1946. If we read the MMM version, what do we find?

We find a narrative structure that’s far more peculiar than the finished film. Here’s how it goes.

The novelization starts with Chuck and Lorna in Havana, en route to their ship. Their carriage stops at the La Habana club, they go in for a drink, and Lorna is stabbed. Arrested, Chuck escapes from the police and takes refuge with Midnight in the tenement. She asks him what brought him to this pass, and in a flashback he tells her. This takes us back to Miami, where he finds Roman’s wallet, meets Lorna, falls in love, and flees with her. The flashback ends with the couple in their cabin aboard ship.

All this conforms to Woolrich’s book, and it strongly suggests that Nebenzal wasn’t blowing smoke when he said in September that he was making the editor “eliminate the flashback.” Evidently Chuck’s flashback existed in both a shooting script and an early version of the film. Its position must have been fairly firm for some time, if as late as September Nebenzal could move it to the front of the film.

Does the novelization follow the Woolrich original after the flashback closes? It does up to a point. From the scene of Chuck and Lorna in their cabin aboard the ship, we return to the present, in Midnight’s apartment. There she advises Chuck on how to investigate Lorna’s death. He finds the photographer dead. Then comes the deviation. Chuck discovers Gino at Mrs. Chin’s shop, burning the incriminating photograph. In the novelization, Gino beats Chuck unconscious and dumps his body down to a cellar.

Now for the big twist. Chuck wakes up in his room in Roman’s mansion. Scott is now back in Miami, completely befuddled. All he can do is stumble to the phone, take some pills, and call Dr. Davidson. The novelization goes on to adhere pretty closely to the rest of the film as we have it.

In the novelization, in other words, the entire action up to this point, in both Havana and Miami, has been Chuck’s dream. Here’s the outline, just to be clear. What’s in green is veridical, what’s in red is not.

{Chuck’s dream begins: No front framing situation.}

Havana (dream): Lorna murdered at the Habana club, Chuck flees, and he meets Midnight. This contains:

Miami flashback (accurate up to the couple’s flight): Chuck hired by Eddie, meets Lorna, escapes with her on ship.

Havana (dream): Chuck investigates, is killed by Gino.

Dream ends: Chuck wakes up in Miami with amnesia.

Chuck goes to Dr. Davidson, who takes him to bar. Chuck rescues Lorna, and Gino and Eddie die in crash.

Epilogue: Couple freed, en route to Havana on ship.

Two things make this pattern striking—one minor, one pretty scandalous.

First, there’s no “front frame”: no situation that puts Chuck in a pre-dream reality. By convention, we don’t have to see him actually fall asleep, but it’s usual to provide circumstances that we can understand retrospectively as preparation for sleep. This is what we get in The Woman in the Window and other then-I-woke-up films. But this movie starts inside the dream.

Nowadays, of course, we’re used to sequences in which a dream is signaled only after the fact. In Out of Sight (1998) we see Karen Sisco sneak up on Jack Foley and then fall to kissing him in his bathtub; then the scene is revealed as a dream. But in the Forties, and even today, it wasn’t usual to have a dream launch the film and go on for over fifty minutes before revealing itself as a dream.

Second, the scandalous aspect. In the novelization’s version of the plot, and presumably the script and an early draft of the film, the dream includes the flashback to Miami. The framing dream material is fantasy, but the flashback is for the most part veridical. Eddie, Gino, Lorna et al. really did most of what we see them doing, even if the encounter with Midnight, the Habana murder, and Chuck’s fight with Gino aren’t real. The only stretch of the Miami flashback that isn’t real is the couple’s flight (which hasn’t happened yet in the waking world).

Here’s why, I suggest, we get those two lines when Chuck visits Davidson. “There doesn’t seem to be any beginning,” Chuck says. Right: because we never saw a beginning, an opening frame for the long dream stretch. And Davidson is at pains to reiterate that the Havana adventure is “dream-stuff” while Roman and Lorna are definitely real. Davidson’s remarks would have served as redundant confirmation for the audience that most of the Miami flashback could be trusted.

During the 1940s, filmmakers competed to find outlandish variants on subjective viewpoints, dreams, and flashbacks. Embedding real scenes as a flashback within a larger, definitely unreal but unmarked dream constitutes a genuine, if screwy innovation for the era.

Fixing it, sort of, in post

On all this circumstantial evidence, I surmise that the novelization’s weird structure was in the script as planned and in the film as initially shot during the summer of 1946. At some point, however—perhaps after previews—Nebenzal thought the better of it. He instructed the editor to move the Miami flashback to the front of the film, where it serves as a conventional chronological introduction to the action. But now what do you do with the Havana stuff? Are you going to kill off Lorna?

No. Clearly Nebenzal and his team had decided to keep the dream idea, but confine it wholly to the Havana episode. That allows Lorna to live at the film’s close. But now they would need to set up the dream within the Miami stretch. So they provided a frame that’s not in the novelization: the scene of Chuck stretching out on his bed as an equivocal prelude to the dream. In other words, a reshoot was called for.