Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or, what puts the Virtual in VR?

Sunday | September 3, 2017 open printable version

open printable version

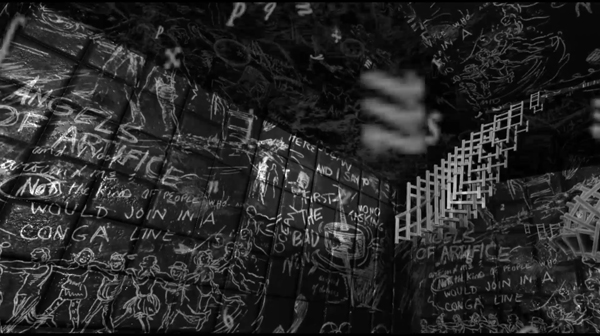

La Camera Insabbiata (2017) by Laurie Anderson and Hsin-chien Huang.

DB here (still at the Mostra):

Kristin and I are Virtual Reality novices, so when we got a chance to sample some pieces at Venice VR, we jumped. The demand was great for the 22 pieces on display, and you had to book each encounter separately in advance. The event was held on its own island, Lazzaretto Vecchio, which was startling in itself; the facility was once a hospital for plague victims.

We took in four pieces in one afternoon and may go back to see some others. We didn’t see exactly the same ones, so my report and speculations are limited to mine. Apart from being fairly wild, sometimes creepy, sensory experiences, they set me thinking about how VR seems to work as a medium.

Angels of artifice

My quartet was a varied assortment, each somewhat parallel to a film genre or narrative prototype. The first was Greenland Melting, by Catherine Upin, Julia Cort, Nonny de la Peña, and Raney Aronson-Rath. It’s part of a Frontline documentary series, and it follows the format, but with immersion. Presenters addressed the camera (me) and took me via helicopter to the glaciers so I could watch them heaving themselves into the sea.

The camera took me underwater as well, and I experimented with voluntarily bobbing under and above the waterline; it worked. Again, as in a film, the transitions between shots was managed through quick dissolves.

La Camera Isabbiata, by Laurie Anderson and Hsin-Chin Huang, is an installation running 20 minutes. It presents a fantasy landscape that you can move through. With two controllers, one in each hand, you choose one of several virtual domains to explore. As far as I could tell, all of them were based on cavernous arrays of blackboards chalked with graffiti. (See the image surmounting today’s entry.)

I first chose the sound domain, which asked me to speak. My words were not only played back to me, but then assumed vase or candy-bowl shapes of gleaming color.

Getting bored with hearing myself and seeing my words made solid, I switched to flying.

Flying was most excellent. Once I figured out how the remotes governed direction, speed, and angle, I could steer a swift path through, over, and around those huge black surfaces. The sense of self-initiated optical flow was powerful, although there were no other cues (e.g., balance, air pressure) to mimic actual flight. But I could have fun playing with this a long time. This was pure subjective POV cinema, or first-person gameplay if you like, and everything was one single shot.

If La Camera Isabbiata put the onus on the user to initiate everything, Draw Me Close: A Memoir by Jordan Tannahill, made me respond to a situation. Once the goggles went on, I was guided to a black-and-white broken-line image of a woman on her sickbed. The artist’s voice-over presented the situation of his mother, dying of cancer, and me-as-him visiting her. Unseen by me, except as her avatar in the goggles, a performer filled the role of the mother, occasionally taking my hand and responding to my responses with more or less scripted comments.

I made my way to a cartoon bed and actually sat on it. The illustrated woman spoke to me, with Tannahill’s voice-over responding. On instructions, I went outside to fetch her paper, but coming back in I moved into a flashback of Tannahill (me) as a little boy playing with Mum. She chatted with me and I feebly responded, and followed her instructions to make colored marks on paper stretched out on the floor.

Later that night Tannahill’s narration guided me to a more unpleasant memory, one reminiscent of Terence Davies’ Distant Voice, Still Lives. It was a minimal narrative to match the images, but I could fill it thanks to the familiarity of the scenario and the tactility of furnishings (bed, door) and physical human contact.

The Deserted, a 55-minute piece, was frankly billed as “a film by Tsai Ming-liang.” A series of fixed long-shots joined by cuts shows a typical Tsai situation: a young man and his mother live in a ruined temple. He apparently administers electrotherapy to his back and chest; he floats in his bath with a fish; it rains in buckets and water comes seeping in to where you’re hovering. A woman in white, perhaps a ghost, appears at times, once in the man’s bathtub.

You make the choices in La Camera Isabbiata, and you role-play in Draw Me Close, but in The Deserted you’re locked down as a witness. No images from the piece seem to be available, but this, from a shot of a camera monitor, roughly indicates the film’s first shot (which isn’t as distorted as this looks).

You can’t move to another spot, and you can’t even crane your neck to peek around corners. You can swivel your head to look 360 degrees horizontally and vertically. But nothing much happens behind your back or over your head. All the action, such as it is, takes place squarely in front of you. Given Tsai’s penchant for static long takes and deep areas of space, The Deserted isn’t putting you inside a real or virtual space; it’s putting you inside a Tsai film.

Reality has the most bandwidth

Since I’m no expert on VR, all I have are initial observations based on this sampling and on a bit of reading.

First observation: VR doesn’t have to be photorealistic to engage you. The image in Draw Me Close is quite impoverished in terms of real-world cues, and the shots of The Deserted are almost shockingly fuzzy. (Tsai, a fan of razor-sharp focus, would never let them in one of his film films.) Other pieces in Venice VR, visible on monitors while users were getting the full dose, are often quite cartoonish. Why are they then so compelling?

E. H. Gombrich suggested long ago that illusion can rely more on stimulation than simulation. That is, choose just a few sensory triggers and you’ll be aroused even if the image isn’t particularly lifelike. Baby geese can, if primed properly, take a box for their mothers, and frogs can snap at anything floating in a fly-ish sort of way around their heads. Outlines, it seems, are central for creatures like us, but they don’t have to be detailed. We also respond, fast and stupidly, to configurations that suggest faces.

Try not to see Jesus, or Janis Joplin, in the tortilla, or a stare on the wings of a Caligo butterfly.

As caricaturists and camouflagers know, a few distinctive features can suffice to summon up the target, and the same goes for the partial and degraded input we see in Draw Me Close and The Deserted. In addition, concepts play a role; our ideas about what to expect in certain surroundings, such as a household, help the illusion cohere. And the information needs to be consistent. When I turn my head in Tsai’s temple, nothing I see contradicts the other cues.

A second point: The VR experiences subtract on some channels of input and compensate on others. Normally, perceptual reality is massively redundant. Our sensory systems reinforce one another. Tilting your head sends signals about balance and vision, while sight and sound and touch and muscular activity offer mutually confirming information. And when things are uncertain, you can always test your environment by moving around.

But the VR systems I encountered impoverish the input on certain channels. Standing in the helicopter of Greenland Melting, I saw the passenger seat beside me as vividly three-dimensional, but when I tried to grab it for support, nothing was there. In The Deserted, I looked down and didn’t see my feet; in fact I was an eye in a bubble floating midway up the wall, where the camera was. And in neither of these pieces could I move voluntarily to poke around much in the space.

I could do that in La Camera Insabbiata, but it was an impoverished environment along other parameters. I could fly, but not touch any of the surfaces–which were without color or shadow, beyond a spotlight that shifted to follow my attention (presumably guided by eye-tracking software). I couldn’t land atop one one of the monoliths, or bump into an edge.

Reciprocally, Draw Me Close provided other sensory inputs: locomotion (though not wholly voluntary), touch (initiated by the performer playing Mum, and by the prop bed and door), and an array of skimpy visual-spatial cues. In principle, smell could have been included. Why not, then, go the whole hog and use a photorealistic rendering of the space and Tannahill’s mother? Perhaps a very faithful representation of Mum and the household would have raised the problem of the Uncanny Valley.

Just as important, we might ask: Since a performer is always required for the piece, why not simply play out the scenes with her and the user? Just go for reality, not virtual reality. I’m guessing that the move toward drawn imagery marks the project as stylized enough to be a media artifact, rather than a piece of interactive theatre. (Though it is partly that.) Here, I’m thinking, the impoverishment of information on certain channels was a deliberate aesthetic choice, rather than being obligated by computer processing power, though that would probably have been a factor too.

One of the biggest compensations for what’s missing in some channels would seem to be good old peripheral vision. This is a very strong cue to immersion, and it can override inputs that contradict it. I remember being in one of the Disney World attractions back in the 1980s, a wraparound theatre that put visitors at the center of a travelogue. Even though there were plenty of cues that you weren’t in front of Buckingham Palace–such as your awareness of people around you looking in different directions–if you concentrated on the filmed display, there was a compelling illusion that you were riding down the street toward the Palace.

Peripheral vision would seem to be a powerful sensory trigger for creatures like us. This was the insight that drove widescreen cinema and the curved screen of Cinerama. But efforts to activate peripheral vision maximally come at a cost. You lose the frame and thus a sense of significantly composed imagery. The Disney display had, as I recall, borders at top and bottom, but in modern VR those too are abolished. VR gives with one hand and takes away with the other, so to speak: Greater immersion yields less of the pictorial structuring that’s inherent in framing. Tsai’s film somewhat overcomes this problem by making the surrounding space neutral and fairly uninformative, but the result still loses the sharp dynamic of offscreen and onscreen space we find in his feature films.

One more thought, which seems more solid than the others. Some have asked whether VR can accommodate narrative. I had presumed so theoretically, but now I’m convinced. Greenland Melting told a real-world story, an alarming one at that. Draw Me Close had emotion-laden scenes, a crisis and climax, and a flashback. The Deserted presented a typical Tsai scenario of humid stasis–a thin narrative, but a narrative. (As often in Tsai, what we miss in psychology and causal density we get in slight spatial changes and pictorial surprises.) It wouldn’t be hard to “narrativize” the Camera Insabbiata soaring, either, say by prodding me to go on a cosmic scavenger hunt. I conclude that of course VR can deal with narrative.

John Landis worried that VR was too wedded to long takes to suit cinematic storytelling. That worry was in turn tied to the assumption that narratives must guide your attention. True! But it’s wrong to assume that only continuity editing can shape a film story. Our attention can be precisely guided through long takes. Indeed, to a degree the sort of open and exploratory attitude some find in VR was already there in locked-down long-take directors like Mizoguchi, Akerman, Hou, and Tsai. And they told stories, plenty of good ones.

Many thanks to Peter Cowie, Alberto Barbera, Michela Lazzarin, and all of their colleagues for inviting and assisting us. Special thanks to Andrea Vesentini for guiding us through the array of events at Venice VR.

For details on Venice VR, go here. Variety covers the Venice event in articles by Elsa Keslassy and Nick Vivarelli. Patrick Frater interviews Tsai on The Deserted here. I found this Wired piece a good VR primer, and Ty Burr offers an update in MIT Technology Review.

Gombrich’s key essay on simulation and stimulation is “Illusion and Art,” available without illustrations here. In full form it appeats in Illusion in Nature and Art, edited by Gombrich and Richard L. Gregory (Scribners, 1973), 193-243.

For discussions of how storytelling cinema guides attention within the shot, see the categories Film Technique: Staging and Tableau Staging.

Better than a cellphone? Viewers at Venice VR.