Welcoming Jews as heroes in an alternate 1924 Vienna

Sunday | August 23, 2020 open printable version

open printable version

The City without Jews (1924).

Kristin here:

Once again Flicker Alley has released a restoration of a film that few have ever heard of. But we all should have heard about this one. And we should have wanted to see it. Now we can.

The City without Jews (Die Stadt ohne Juden) is an Austrian silent film released in 1924 and directed by H. K. Breslauer. It falls into the brief cycle of films about Jews released in the first half of the 1920s. I’ve written about this briefly in regard to Flicker Alley’s earlier Blu-ray of another film in this cycle, E. A. Dupont’s Das alte Gesetz (1923). The other notable Jewish-themed films are the Expressionist classic Der Golem: Wie er in der Welt kam (Paul Wegener and Carl Boese, 1920) and Carl Dreyer’s first German film, Die Gezeichneten (“The Stigmatized Ones,” called in Danish Elsker hverandre, or “Love One Another,” 1922). Thus The City without Jews is, as far as I know, the last entry in this cycle.

The Russian Revolution and civil war had driven many “Eastern Jews” into Europe, and they, created an anti-immigrant sentiment that grew into a more generalized intolerance toward the more assimilated Jews already in these countries. The earlier films had made little reference to the current growth of antisemitism in Europe and particularly in Germany and Austria. Der Golem was a period fantasy, Dreyer’s film dealt with pogroms in 1905 Russia, and Das alte Gesetz was a drama largely about conservative attitudes toward assimilation within the Jewish community.

Beslauer’s film was based on a satirical novel of the same name (1922) by Hugo Bettauer. It has proven his most famous novel, though undoubtedly in film circles he is best known as the author of Der freudlose Gasse, the source for G. W. Pabst’s 1925 classic of New Objectivity. Bettauer was a controversial figure, given the rising right-wing extremism in the mid-1920s. Perhaps spurred by the release of the film, a dental technician and member of the National Socialist Party assassinated Bettauer in early 1925; the assassin was sentenced to 18 months in a mental clinic and then walked free.

Despite an initial success in Vienna, The City without Jews was shown only a few times abroad, in various censored or abridged versions. The last known screening was in the Netherlands in 1933, as a anti-Nazi film. Portions of an incomplete print of that version, added to reels found in 2015 in a Parisian flea market, formed the basis of the current restoration. Given its sources, the result can hardly be identical to the original, but it plays very smoothly, and there are no noticeable remnants of gaps or re-editing. An account of the restoration is offered by Anna Dobringer as one of several brief essays in the booklet accompanying the dual DVD/Blu-ray release by Flicker Alley.

A satirical, serious picture of antisemitism

Of the four Jewish-themed films mentioned above, The City without Jews is the only overtly political one. Beslauer’s film, the action takes place in “Utopia,” a thinly disguised Vienna (where the film was shot), and many of the main characters are the Councillors and Chancellor.

The film starts by emphasizing that assimilated Jews already established in Utopia worship alongside the recent Eastern Jews, as suggested by the two foreground figures in the opening synagogue scene (see top). The government finds it convenient to blame various problems, such as rising prices and unemployment, as well as the fall of the country’s currency, on the Jewish population. With mounting popular unrest, the Chancellor accedes to the idea of expelling all Jews from the city.

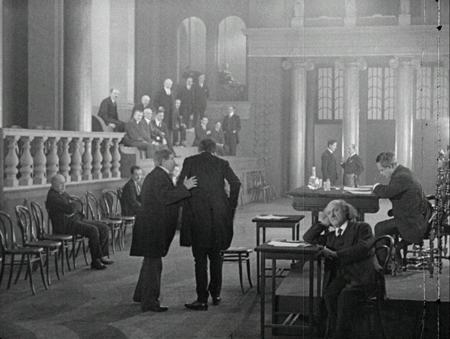

The result is a rather uneasy balance in the early portions of the film between satirical views of the local politicians, officials, and businessmen, and the very real sufferings of the Jews and their Christian supporters and spouses. (The film is a quite polished and expensive production, as the legislative chamber, above, shows.) The Christian officials are treated as caricatures, rather similar to the way officials are portrayed in Soviet films of the second half of the 1920s–which Breslauer, of course, could not have seen.

The scenes of the entire Jewish population being expelled, on the other hand, is treated quite seriously and fairly realistically. Scenes of families being dragged out of their homes are not at all humorous, and the departure en masse by train calls to mind methods that were to be used in reality little over a decade later–though here the trains are ordinary passenger ones rather than cattle-cars.

A rather odd premise which the film emphasizes is the impact that the expulsion has on marriages between Jews and Christians. No fewer than five mixed couples of various classes are made prominent, and all are ripped apart. One involves a rabid anti-Semite, portrayed as a drunken dolt. His daughter has married a Jewish man, and they have a daughter. The scene of the husband’s departure shows the anti-Semite (in dark coat at the center below) grieving along with his daughter as they watch the little girl saying good-bye to her father.

The author and filmmakers seem to understand well the familiar phenomenon of the bigot who is only brought to sympathize when people who are discriminated against turn out to be members of their own family.

Pure satire takes over

Once the Jews are gone, the satirical approach fully takes over. It turns out that the Jews had been the foundation of everything good and strong in the Utopian society. Businesses collapse, the currency falls, foreign countries boycott Utopia, and foreign banks (being controlled by Jews) refuse to loan the failing government money. The Chancellor and his allies lament that they no longer can blame the Jews for these problems.

More amusingly, the culture falls apart. High society people who had only dressed elegantly because Jews did decide that they don’t need to buy the latest fashions. One powerful businessman who runs an expensive ladies’ clothes emporium discovers that his establishment is no longer profitable (below left). Austrian men abandon their dignified suits and revert to their casual clothes and giant tankards of beer (right). The sophistication associated with the Jews has disappeared. (All this forgets the recently arrived Eastern Jews, with the action concentrating on the very much assimilated ones.)

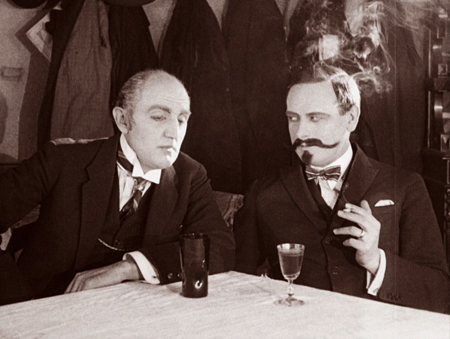

Among the five Jewish-Christian couples separated by the expulsion is Leo Strakosch, who is engaged to the daughter of one of the local Councillors. He emerges as the film’s protagonist, returning to Utopia in the persona of a Parisian painter and Roman Catholic. His disguise makes him look like a thinner version of Dr. Mabuse (top of this section), and one suspects that Lang’s two-part film, released in 1922, had not gone unnoticed.

Like Mabuse, Leo manipulates the dire political situation, campaigning for a repeal of the expulsion order and a return of the Jews as the only way to save Utopia’s situation. He does so, of course, in a good cause. Ultimately the decision concerning the repeal hangs on a single vote lacking for the two-thirds majority needed to rescind the order.

Leo gets one of the Councillors drunk and sends him away during the vote, thus causing the repeal to succeed.

The result is a huge success. Jews return, sales and the currency rise, mixed couples are re-united, and the government now credits the returning Jews with the restoration of the country’s health. Strakosch, now out of his disguise, is greeted as the first returnee by cheering crowds and bouquets.

Expressionism as revenge

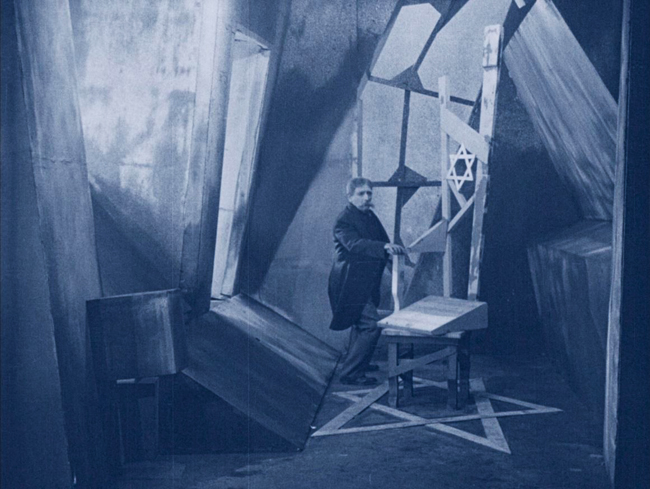

The drunken Councillor whose lacking vote caused the return of the Jews ends up in a scene that quite explicitly imitates the end of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. He dreams of being imprisoned in a cell with Jewish stars built into the scenery (see bottom). He recoils in horror at the sight. This is followed by a shot of a doctor (above) who declares, “A strange case of delirium, my dear colleague. The man imagines himself to be a Zionist.” I dearly hoped that he would go on to say, “I think I know how to cure him now,” but it was not to be. Obviously the diagnosis is completely wrong, since the Councillor is terrified by the Jewish imagery in his cell. But of course, Dr. Caligari’s diagnosis may have been wrong as well.

The film is accompanied by a charming score, provided by pianist Donald Sosin and violinist Alicia Svigals. For a list of bonus materials, click on the link at the top of this post.

The City without Jews has fallen into the state of an obscure film, no doubt, but it deserves more attention now than it received at the time of its release. It has become a cliché to point out that a film of the past speaks to our current world situation. Still, this film does.

Thanks to Jeffery Massino and the team at Flicker Alley!