Archive for the 'Experimental film' Category

German classics for the pandemic and beyond

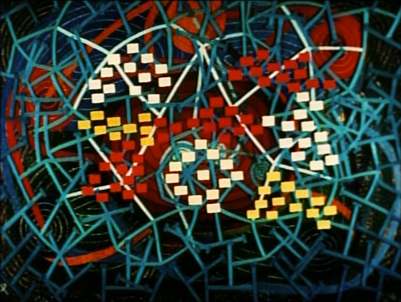

Kreise (Circles, 1934).

Kristin here:

Recently I acquired discs of the work of two important German directors of the silent and early sound periods. The first is a new Blu-ray/DVD edition of Paul Leni’s Waxworks from Flicker Alley. The second is a pair of DVD releases of Oskar Fischinger shorts, which I recently ordered from The Center for Visual Music, co-founded by Fischinger’s daughter Barbara. All are vital for anyone interested in these two major figures in German film history.

Telling scary stories

As with so many cinema classics, I first saw Paul Leni’s Wachsfigurenkabinett (Waxworks) during my grad-school years. The print was 16mm and very dark. It was hard to get any real sense of its pictorial design. I had seen Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari in my first film course and had been hugely intrigued by how different it was from the movies I was used to. It was one of the films that lured me into cinema studies. Since then I have been partial to German silents of the 1920s and especially those of the Expressionist movement. Waxworks was made in 1924, which also saw such high points of the decade as Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen, F. W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh, and Carl Dreyer’s second German-made film, Michael. Still, the poor print did not give much sense of how it fit into the creative trends of the mid-1920s. Later I saw it in a 35mm archival print on a flat-bed viewer. That print was also too dark to allow a judgment of its aesthetic and historic importance.

At last, however, a restoration by the Deutsche Kinemathek and the Cineteca di Bologna (released on combination Blu-ray and DVD by Flicker Alley in the USA, from the British Eureka! print) has revealed the set design and impressively bold lighting that suggest why it is considered one of the classics of the Expressionist movement.

While Expressionist stage plays had tended to use stylized settings and acting to create frantic denunciations of contemporary politics and society, German Expressionist films usually remained within popular genres. Horror, fantasy, and science fiction could justify the distortions of the sets as ways of creating strange, often menacing worlds. Waxworks fits right into the horror genre. Set in a carnival sideshow booth, the frame story sets up the premise of the proprietor hiring a young man to write publicity tales about three wax figures of monstrous figures from history and legend: Caliph Haroun-al-Raschid, Ivan the Terrible, and Jack the Ripper. We see the three tales played out as the hero writes them.

The villains are played by Emil Jannings (see bottom), Conrad Veidt, and Werner Krauss, three top male stars of the era. They do not, however, appear together, since their stories are self-contained vignettes. The narrative returns between the imbedded stories to the table where the young man writes and a romance quickly blooms between him and the sideshow owner’s daughter. The two actors playing them, Wilhelm Dieterle (later to have a career as a director in Hollywood as William Dieterle) and Olga Belajeff, appear as the central victimized couple in each inner tale.

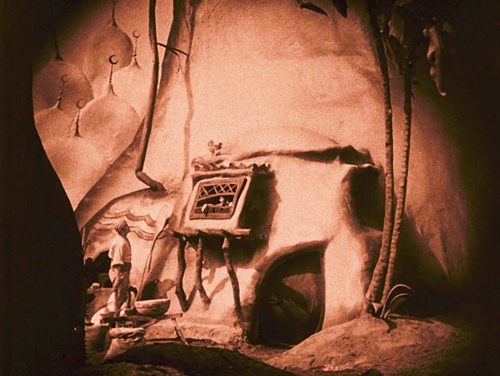

A different style is used for each of these three tales. The first story (in this print, at least) tells of Haroun trying to seduce the beautiful wife of a Baghdad baker. The settings are of the melting-clay variety familiar from Der Golem and Kriemhild’s Revenge. The image at the top of this section shows the baker’s home, with its sagging doorway and artificial trees. The image below displays a typical technique of designing sets to echo the shapes of the actors, as the doorway in the rear imitates Haroun’s blobby outline in the foreground.

The Ivan the Terrible episode comes next, maintaining the blobby look, but with more solid-looking, often symmetrical sets. Here Ivan emerges from his palace.

The brief third episode has suspenseful visions of Jack the Ripper pursuing the couple in nightmare fashion, with multiple superimpositions of the implacable killer.

Apart from these techniques, the improved visual quality of the film reveals a dark style of lighting that helps explain where the influences on Hollywood film noir came from. The opening of the frame story takes place at night, and a chiaroscuro look is established with a sophisticated use of Hollywood’s three-point lighting, which had only reached Germany a few years earlier.

There are some other daring uses of foreground silhouettes, as when the jealous baker watches his wife move away into darkness (left) or Ivan’s poison-maker realizes that he has been doomed to die (right).

These are only a few of the many frame-grabs I made while watching this visually dramatic print. I could post many more, but I’ll end with this interesting comparison that I noticed. On the left, a shot from the Haroun episode as he plays chess with courtiers, and on the right, an interior of the house where the Woman from the City is lodging in Murnau’s Sunrise (1927).

The Waxworks we see today is not the original German version. The original negative was lost in a Paris customs-house fire in 1925. The most complete surviving version was the one released in the UK in 1926. Where it was deteriorated, footage from other surviving release prints was substituted. This English version was about 25 minutes shorter than the German one, with the footage removed mainly from the frame story and from the exposition about the wedding of the young couple in the Ivan episode. The premiere of the film in Berlin had the stories in a different order: Ivan, then Jack, than Haroun. Possibly this aimed at a more cheerful ending for the film, but the order was changed shortly thereafter, presumably to that of the British and other release versions.

The severe hyperinflation in Germany in the mid-1920s led to financial problems, and these curtailed the shooting of the film. One intended episode about Rinaldo Rinaldini, a fictional “Robber Captain,” was never shot, though the wax figure of Rinaldini is clearly visible in the sideshow lineup of miscreants. The Jack the Ripper story was never shot in full, though the shapeless nightmare sequence was shot without benefit of script. It ends up as a short but frightening climax to the film. As a result of all this, the Haroun episode is fairly lengthy, the Ivan one less so, and the Jack the Ripper one brief but memorable. Essentially what we have is a restoration of the British version.

The restored version uses the intertitles from the British print, as the German ones have not survived, and the tinting and toning are also based on the British print. The accompanying booklet has an essay on the history of the film and its versions by Richard Combs, a sketch of Leni’s career by Philip Kemp, and a description of the restoration by Julia Wallmüller. Adrian Martin contributes the insightful commentary. One charming extra is a short, Rebus-Film Nr. 1 (1926), part of a series of eight brief crossword-puzzles that audiences could play along with in the program of short subjects before the feature. These included animations and experimental montage-style superimpositions done by the brilliant German cinematographer Guido Seeber. I got all the answers right. Could you? (Actually, they’re very easy, as they would have to be in a theatrical situation.) The Blu-ray is regions A, B, and C. For more technical and historical background on the film, see Jan Christopher-Horak’s review of the Flicker Alley release. (It’s entry number 260; you’ll need to scroll down to find it.)

Leni continued on in the horror mode late in his career in Hollywood, making The Cat and the Canary (1927), The Man Who Laughs (1928), and The Last Warning (1928), all at Universal. These, along with the various films of Lon Chaney, notably The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1922) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), built the foundation for Universal’s famous horror films of the 1930s.

The Visual Music of Oskar Fischinger

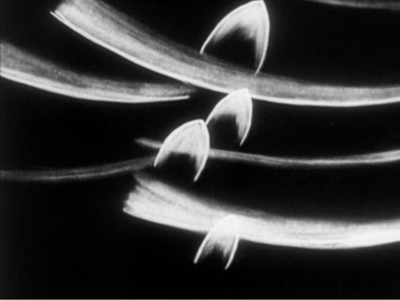

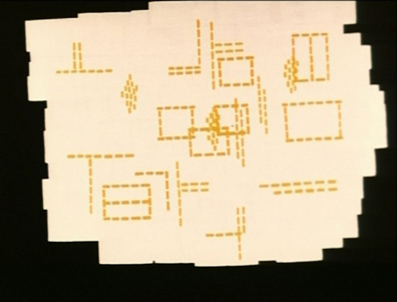

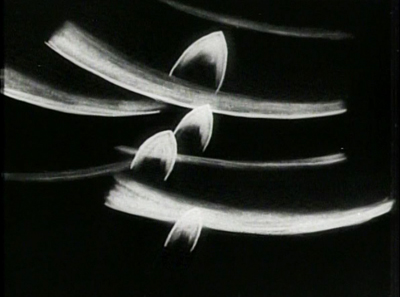

In my recent year-end entry “The Ten Best Films of … 1930,” I included Oskar Fischinger’s series of “Studies” from that year: short films of white shapes (drawn in charcoal on white paper and shown in negative) zipping around the screen in time to musical pieces. These run from Study No. 2 to Study No. 7, though others numbered up to 12 were made in 1931-32. Study No. 4 is apparently lost, and No. 1 is listed on the Fischinger Archive website (linked below) as having been accompanied by live organ music and never released on home video, while the subsequent ones were done with recorded music.

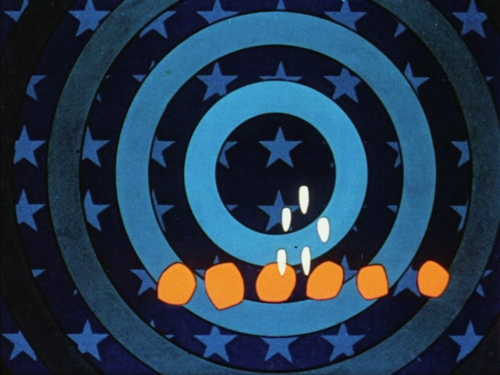

In that entry I linked to the Center for Visual Music as the sole source of two DVDs collecting Fischinger’s work. (I have discovered one other source. See the end of this entry.) At the time I had ordered them, and they subsequently have arrived. It was a great pleasure to sit down and watch both straight through. The films are delightful and lift the spirits. My viewing was on Inauguration Day, when my spirits were already quite lifted, and Fischinger’s An American March (1941), set to Sousa’s “The Stars and Stripes Forever” (above), was especially cheering on a day when our country got rid of a fake president and welcomed a real one.

Although Fischinger used both popular and classical pieces, he retained a similar, recognizable style for both. The black-and-white films were relatively simple, as in Study No. 6.

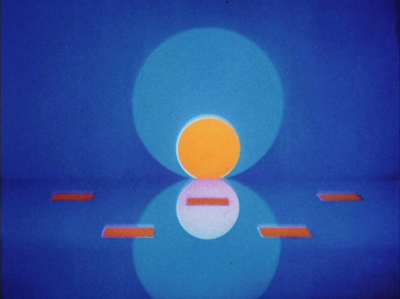

Like his contemporary, New Zealand animator Len Lye, Fischinger adopted color early and used the soft but extraordinarily vibrant Gaspar Color system. Most of his films of the 1930s employed it, as in Circles (at top) and Composition in Blue (1935).

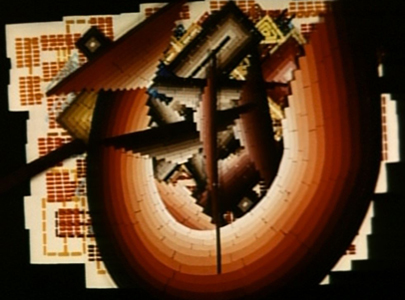

His masterpiece, at least in my opinion, is his last significant film, Motion Painting No. 1. It is his longest film at eleven minutes and is set to Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3. It also departs from his usual modes of animation. Rather than substituting a new drawing or moving abstract shapes in space slightly between exposures, he added a brushstroke per frame, creating a continuously moving line that gradually created a series of compositions that changed the image completely as the line proceeded relentlessly and obliterated what went before. Thus across the film there is no pause in the line’s movement as it paints over its earlier progression. Here are some of the stages of its mutations. (Spoiler alert!)

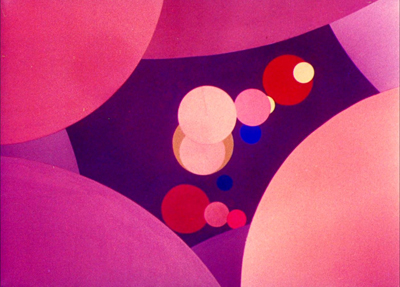

While these two discs contain nearly all of Fischinger’s important films, a conspicuous absence is An Optical Poem, which is an abstract animation of the usual sort made by Fischinger but for a major studio. MGM produced it as one of the seven-minute cartoons that were shown among the shorts in movie-theater programs for decades. Set to Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody Number 2,” it’s typical Fischinger, with lively colored discs and other shapes darting around. The main difference is that here he was working in Technicolor. As smaller discs pass behind larger ones, a distinct sense of depth is often achieved.

The reason for An Optical Poem‘s absence from the CVM discs is presumably because it is the only Fischinger film not controlled by the Estate. Fortunately the gap has been filled by its inclusion in Flicker Alley’s set, “Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970,” which I reviewed when it was released in 2015. Flicker Alley obtained permission from Warner Bros. and Turner Entertainment, which now control MGM’s library. This allowed them to include the original MGM logo and title, plus an introductory opening text that tries to prepare the audience for what’s to come. (These are missing from the prints posted online.)

Between the two CVM discs and the Flicker Alley set, we now have good copies of all but some minor, often unfinished works by Fischinger. The CVM discs do not contain much in the way of supplements, but one can get much more information from William Moritz’s Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fischinger (2004). More information, including a bibliography of books and articles on the filmmaker, can be found on the website of CVM’s Fischinger Archive. Fischinger died in 1967, and several years later his wife Elfriede sent a collection of his equipment and the material used in his animated films to the Deutsches Filminstitut in Frankfurt. This collection included the plexiglass sheets upon which Motion Painting No. 1 was created.

Thanks to Lee Tsiantis for a correction to the Oskar Fischinger section!

January 27, 2021. Thanks to Cindy Keefer of the Center for Visual Music for providing some additional information on the availability of Fischinger’s films. A number of art museums and specialty bookshops have sold the CVM DVDs in the past. The only place that is still doing so, as far as I can tell, is Walther Koenig‘s fine bookshop in Berlin. The CVM also has some excerpts and complete films on their Vimeo channel.

The ten best films of … 1930

The Blue Angel (1930)

Kristin here:

The end of this horrendous year is fast approaching, though we are still facing a long struggle to end the pandemic. On a happier note, it is also time for a little distraction in the form of my annual year-end round-up of the ten best films of ninety years ago. 1930 was also a grim year, with the Depression well established and nowhere close to its end. Herbert Hoover decided not to use federal governmental powers to help end the crisis (sound familiar?) and eventually was cashiered into a 32-year retirement, though he continued to oppose Roosevelt’s policies. At least we don’t face that long a stretch of down time with the current “president.”

I discovered that 1930 did not produce many masterpieces. There are some obvious titles on my final list, as always, but some of the films are good but not great. In any other year they would not have made the cut. (The contrast with 1927, for example, is pretty stark.) Presumably one major reason is that filmmakers were still struggling with the introduction of sound. Fritz Lang didn’t release a film that year, though he came roaring back with M in 1931, as assured a treatment of sound cinema as one could find during those early days. (For those of you who subscribe to The Criterion Channel, I contributed a video essay on sound in M to David’s, Jeff Smith’s, and my series, also called “Observations on Film Art.”) Eisenstein was off in Hollywood unsuccessfully trying to make a film for Paramount and about to fall in love with Mexico. With one notable exception, Hollywood’s important auteurs made no films or minor films or films that don’t survive.

This dearth of really great films will be short-lived. From 1932 on, I shall no doubt have the opposite problem. For now, here are my picks. All the films are worth seeing, though good copies or even any copies of some are hard to track down. (The idea that all films are available to stream online is as absurd as when, back in 2007 when I wrote “The Celestial Multiplex.”) Some of my illustrations in this entry are subpar, but 1930 does not seem to be a year that studios and home-video companies are mining for titles to restore. I hope this entry will give them a few ideas.

I try not to include more than one film by the same director in these entries, aiming for variety and coverage. This year’s most prolific great directors were Josef von Sternberg and Yasujiro Ozu, who together could have filled in half the ten slots, but I have stuck to my guideline. (When we reach 1932 and 1933, I may be tempted to make an exception for Ozu.)

Given that sound developed at a different pace in different countries, some of this year’s films are silent.

For previous 90-year-ago lists, see 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928 and 1929.

Dovzhenko’s Earth

Some of the films on my top-ten list this year may raise eyebrows, but Earth is probably my least controversial choice. It remains one of the last classics of the Soviet Montage movement.

The policy of merging small farms into collective ones had begun in 1927 as part of the First Five-Year Plan. In 1929-30, the push increased, with the seizure of the assets of the more prosperous peasants who resisted collectivization, termed kulaks. Major films were made with the aim of villainizing the kulaks and emphasizing the backbreaking labor involved in traditional, non-mechanized farming. Eager young peasants were hailed as heroes, and tractors appeared as the means to greatly increase wheat yields–wheat which was often seized and sent to the cities to enable rapid industrialization.

Eisenstein had promoted collectivization with his Old and New in 1929, and Dovzhenko followed a year later with Earth. While Eisenstein’s approach had been sarcastic and comic, Dovzhenko pursued his poetic approach to cinema. The opening celebrates the fecundity of the earth and the cycles of nature. The famous opening juxtaposes a peasant girl’s face with a large sunflower. Semion, an aged peasant, is calmly, even cheerfully awaiting his imminent death, lying on a blanket and surrounded by heaps of apples.

A kulak family is soon introduced, angry at the idea that their possessions will be seized. The head of the family declares that he will kill his animals rather than turn them over, and he tries to attack his horse with an axe.

The arrival of the village’s new government-provided tractor marks a shift to an emphasis on the advantages of collective farming. As it approaches, the kulaks stand watching and mocking the idea of a machine taking over. In one shot, an elderly kulak stands framed against the sky, his wealth indicated by the presence of a hefty cow. The tractor temporarily halts, but it turns out that the radiator is dry. The simple solution is for the collective members to urinate into it.

Earth is a visually beautiful film, but like other Soviet classics I have complained about, there is no decent print of it available. The old Kino disc groups it with Pudovkin’s The End of St. Petersburg (the cropping of which I mentiooned in the 1927 entry) and Chess Fever. The copy of Earth is too dark and indistinct. To get some frames for illustrations, I watched the visually superior copy on YouTube, but there the images are cropped to a widescreen format. Just as bad, there are ads scattered through it, including one in the middle of Vasyl’s twilight dance in the road just before he is shot!

As before, I must end by pointing out that an archival restoration and a Blu-ray release are in order.

Ozu debuts on the list

Although after 1937 there are years when Ozu did not make a film, he will likely feature on these lists as long as I continue to post them. In 1930 he made six features and a short. Only three survive: Walk Cheerfully, I Flunked, But … , and That Night’s Wife. I’ve chosen the last, though Walk Cheerfully is a viable candidate as well. Sound was adopted slowly in Japan, and Ozu held out until 1936 before releasing his first talkie, The Only Son, which will doubtless feature on my list for that year.

The British Film Institute released That Night’s Wife in a boxed set called “The Gangster Films,” along with Walk Cheerfully and Dragnet Girl. Yes, Ozu made gangster films, including the wonderful Dragnet Girl, the film that might lead me to make my exception in the 1933 entry.

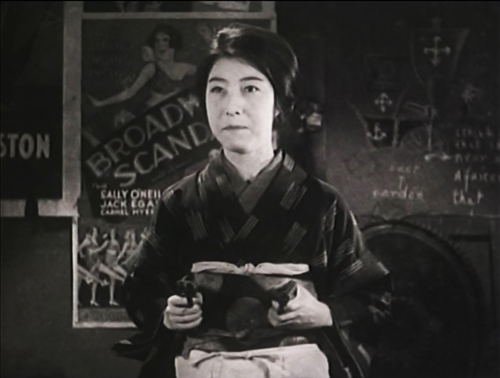

That Night’s Wife, though, is not really a gangster film. Shuji, the father of a daughter with a potentially fatal illness, is not a gang member but a decent working man who stages a hold-up to get money for her medicine. Ozu handles this hoary plot premise with his usual unconventional approach.

The opening, with its shots of dark, empty streets through which the police chase Shuji, is film noir ahead of its time. We soon are introduced to his worried wife, Mayumi, tending the little girl. She’s cute but has a distinctly bratty streak so common to Ozu children. This and fairly frequent moments of subtle humor help Ozu avoid a purely melodramatic presentation of the situation.

Once Shuji arrives at home, Mayumi gets him to confess what he has done. He intends to turn himself in after the daughter’s crisis passes, but a gruff detective who has posed as a cabby to find out where he lives, appears. Being told that the daughter will only survive if she lasts through the night, the Detective agrees to stay and settles in to guard his prisoner. Mayumi reveals her inner toughness and determination to defend her husband. At one point the Detective dozes off and she steals his gun and points it and her husband’s pistol at him, urging Shuji to escape (above). That shot, by the way, shows a motif typical of early Ozu films: having posters, often for American movies, visible on the walls behind the characters.

That Night’s Wife doesn’t display the fully mature Ozu style, but no one would mistake it for a film by another director. He has already mastered the perfect match on action, and he uses one in the early scene where Mayumi sits down as the doctor tends the daughter. Ozu cuts in with a move across the axis of action that places us 180 degrees on the other side of her.

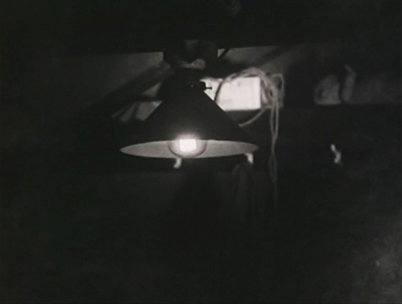

Ozu is not using 360-degree space consistently yet, but he’s playing with the idea. Twice he has transitions that move through a series of adjacent spaces, one of his key devices and one that will last throughout his career. Here we move from the worried Mayumi to Shuji, trying to elude the police after the theft.

There’s a lyrical motif mutating from shot to shot: worried wife, interior lamp, interior plant against wood, outdoor light with leaves, stone building with the shadows of leaves, and stone building with the subject of Mayumi’s thoughts, cowering. But causally the four “extra” shots tell us little about where Shuji is in relation to the home he seeks to reach.

I took these frames from the BFI set, but in the US Criterion released the same three films in its Eclipse brand under the more accurate title “Silent Ozu – Three Crime Dramas.” (I Flunked, But … is in the BFI’s four-film set, “The Student Comedies.” Criterion hasn’t released a DVD of it, but it is streaming on the Channel.)

The Germans’ sound advantage

Unlike other countries, Germany developed its own sound system, owned by the Tobis-Klangfilm company. Tobis was initially able to use court injunctions to keep American films out of the German market. In 1930, this pressure led ERPI and RCA, owners of patents on the major US sound-on-film systems, to form a cartel in conjunction with Tobis, which had producing and distribution subsidiaries throughout Europe. Tobis-Klangfilm continued to dominate European sound recording and reproduction until the beginning of World War II.

Partly as a result of this technical advantage, several early 1930s German films became classics, though not all of them are known abroad.

One internationally famous classic is The Blue Angel. I’ve mentioned that von Sternberg was among the most prolific of major directors in 1930. I debated whether to put this or Morocco on the list. If cinematography were the main criterion, Morocco would have been the choice. Not surprisingly, Lee Garmes’s camerawork and lighting is spectacularly good.

I initially saw The Blue Angel decades ago, in grad school. It was the usual hazy 16mm print of the American release version. Watching it again in the German version, remastered from a 35mm negative, was a revelation. Not that it will ever be one of my favorites. It has its problems. The motif of the clown, implied to be Lola’s degraded ex-lover, is heavy-handed. Emil Jannings’ lumbering performance as Prof. Rath is at odds with the casual realism of the other performances. The time-passing montage accomplished via a hair-curler ripping down a series of calendar pages creates a time gap of years passing and the characters–especially Lola–have changed radically. Her change from a kind attitude toward Rath to cruelty and indifference is logical, given his passive decline from professor to clown, but it is presented too abruptly. Still, in my opinion the film’s pluses outweigh its minuses.

The Blue Angel, seen in a good print, is wonderfully photographed as well (see top). It may not have Lee Garmes, but it has Günther Rittau (co-cinematographer with Hans Schneeberger). He had lensed Die Nibelungen, Metropolis, Heimkehr, and Asphalt. He brings a dark look to the film, as in these shots of Rath in dignified professor mode and later onstage in a caricature of his former self.

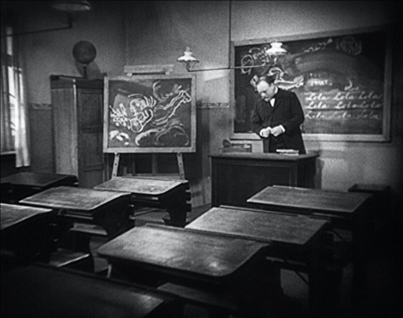

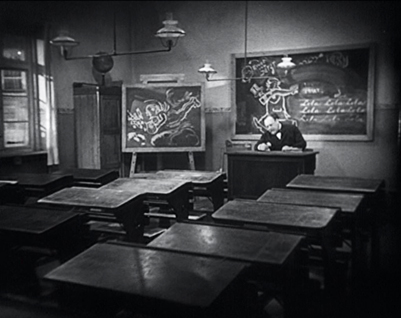

The camera movements are rare and unobtrusive. A visual motif set up early on shows the bustling classroom that Rath presides over, where despite the students’ dislike of him, they obey his strict commands. Later, in after Rath has visited The Blue Angel and met Lola, his blackboard is covered with caricatures and insults drawn there by the students to mock his obsession with Lola. A slow track back emphasizes the empty classroom as he sits at his desk, his authority over the students gone.

No doubt it’s a matter of taste, but I find Marlene Dietrich’s performance here more attractive than in Morocco–and it is, of course, central to the film’s appeal. Her amused playfulness with Rath, her quietly sarcastic attitude toward her sexuality being The Blue Angel’s main attraction, and her frequent bits of business with props unrelated to the story all differ considerably from her Hollywood performances. She has a natural glamor here that will disappear in her roles for von Sternberg in Hollywood.

After this film, von Sternberg made Dietrich a Hollywood symbol of glamor, but as a result she tends to be less spontaneous and active, with the camera and lighting lingering over her. Basically her glamor became more sultry. The result has its own appeal (and Shanghai Express is a good bet for a place on the 1932 list), but it is revealing to see her performing in a way that she only recaptured occasionally, if at all, in her subsequent films.

The frames were taken from the Kino on Video two-disc set, which has both the German and truncated American versions, as well as some supplements. It was subsequently released on Blu-ray, but I haven’t seen that version.

I always try to call attention to little-known films rather than sticking to the conventional classics for the whole list–and there aren’t a lot of such classics this year anyway. This time it’s a charming, imaginative musical romance, Die Drei von der Tankstelle, or “The Three from the Filling Station,” directed by Wilhelm Thiele and starring Lilian Harvey and Willy Fritsch. It was so popular that it outgrossed The Blue Angel in Germany.

Three carefree young men, who start off driving in a car and singing about friendship, arrive in their lavish shared home to discover that they are bankrupt. Low on gas, they are inspired to start their own filling station. They sing a nonsense song, “Kuckuck” (the German equivalent of “cuckoo”) as their belongings are hauled away, and they give this name to their art-deco filling station.

Lilian (the heroine’s name as well) shows up in search of gas for her roadster, and the three men fall in love with her. The rest of the film involves their competition over her. Naturally she chooses Willy (Fritsch’s character name). The two were often paired in later German films of the 1930s and became the ideal movie couple.

The film maintains its playful, often silly tone until the end. As Lilian and Willy are united before a closed theatrical curtain, she turns front and says, “People! The public!” There is an objection that this is not the way to end an operetta and the curtain opens to reveal the entire cast as well as additional dancers and singers performing a lively and somewhat chaotic grand-finale number.

I originally saw this film at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique (now the Cinematek). As it does not circulate in the US on home-video, I have taken these low-quality frames from a homemade DVD, probably originally dubbed from an unsubtitled German VHS copy. It is available on a German DVD, since it is considered a perennial classic there. Unfortunately it has no subtitles. (The German manufacturers do not seem to have cottoned onto what their counterparts in other European nations–notably France–have: that if you include optional English subtitles, you can sell more copies.)

I hope, however, that eventually someone at the DVD/Blu-ray companies will discover this very entertaining film and make it more widely available.

A German director abroad

F. W. Murnau’s City Girl is another of those films I saw in a poor print decades ago and respect a great deal more after seeing it in a good version and knowing more about film than I did then. I wouldn’t put it in the same league as some of his earlier films, but for a 1930 list, it stands out.

Murnau was already on the way out at Fox when he was making the film. After his departure, the film was “finished,” including some dialogue scenes that were inserted. As with several other films of the era, such as Borzage’s Lucky Star and Duvivier’s Au Bonheur des Dames (see below), we are lucky in that only the silent version survives. The restored dialogue scenes in Fejos’s Lonesome show how ghastly these added interludes could be. (My apologies to the restorers. Obviously somebody had to do it.)

The heroine of the title is Kate, a waitress in a busy Chicago diner. Disillusioned by the obnoxious male customers she must cope with and lonely in her sparse apartment (below), she dreams of the apparently peaceful countryside that she sees in pictures. Lem wanders in for a meal, having been sent by his tyrannical father to sell the harvest from their wheat farm in Minnesota. He becomes a regular customer as he stays in Chicago waiting for the price of wheat to rise. His friendly, courteous behavior confirms her idealization of rural life, and they fall in love. Once she arrives at the farm, however, her illusions are shattered by the father’s violent rejection and the loutish behavior of a gang hired to help with the harvest, against neither of whom Lem seems able to defend her.

As in Sunrise, City Girl creates a contrast of city and country, though on the whole the city here comes across as more oppressive than the relatively friendly treatment the couple in Sunrise receive there. Sunrise spends half the film presenting the aftermath to the couple’s reconciliation, while City Girl has a grimmer tone, and the happy ending arrives very suddenly and briefly.

According to Janet Bergstrom’s informative essay accompanying the “Murnau, Borzage and Fox” DVD boxed-set, Murnau initially wanted to film in Grandeur, a widescreen format of the day, but the budget wouldn’t allow it. (I suppose the effect might have worked, as the 70mm version of Days of Heaven demonstrates with a similar locale.) Perhaps it was just as well. Cinematographer Ernest Palmer has handled the landscapes well (top of this section) and given a distinctly documentary look to the harvest scenes.

The restored version of the film in the Fox boxed-set is excellent, but that box is long out of print. British company Eureka! has released City Girl on Blu-ray, which should look even better, available as an import on Amazon.com in the US (where it is listed as Blu-ray but is the same edition as is listed on amazon.co.uk as dual-format Blu-ray/DVD).

The French between silence and sound

René Clair has long been considered one of the directors whose early sound films were among the most imaginative and technically sophisticated. Indeed, that era was perhaps the high point of his career, with Sous les toits de Paris (1930), Le Million (1931), and À nous la liberté (1932) coming out in quick succession. The first two were made for the French subsidiary of Tobis, Films Sonores Tobis, which produced French films in its Epinay Studios. Its prosperity and technical sophistication are evident in the large sets constructed for Sous les toits.

The film centers on Albert, who makes his living selling sheet music to passersby in the street and leading them in sing-alongs. In the opening scene, a small crowd joins in a song called “Sous les toits de Paris” (above). He falls in love with Pola, who is claimed by Fred, one of the many thugs played by Gaston Modot across his career. She moves in with Albert, but when he is framed for a crime committed by Fred’s gang and sent to jail, she takes up with Albert’s best friend.

This light tale gives Clair the opportunity to show off the flexibility and even flashiness of his style. The opening shot is a long crane movement descending from chimneys against the sky to the crowd singing along with Albert. Clair also uses a variety of camera angles, as in the low-angle still above.

There are several carefully lit street scenes, including this one shot in depth with both characters’ backs to the camera as Albert spots Pola outside a bar.

The climactic scene involves a tense conversation between Albert and his pal as Pola looks on. Clair shoots the two men in shot/reverse shot through glass doors, so that we do not hear them but only watch their actions and faces in a deliberate reversion to silent cinema.

Sous les toits de Paris is still in print as a DVD from The Criterion Collection. (An early issue, number 161.)

At least in the US, Julien Duvivier is not as familiar as Clair, being known mainly for Pépé le Moko, but his reputation is rightly growing. David did his part in promoting Duvivier by contributing a video analysis of his 1941 Hollywood romance Lydia on The Criterion Channel.

I don’t know whether Duvivier was inspired by L’Herbier’s L’Argent (which featured on my 1928 list) to make Au Bonheur des Dames, but there are certainly similarities between them. L’Herbier’s film was adapted from the eighteenth novel in Zola’s Rougon-Macquart series, published in 1891, but the film updated the story to the 1920s. Au Bonheur des Dames was adapted from the eleventh novel in the series (1883) and also updated. L’Argent showed the harm done by large banks, while Au Bonheur des Dames deals with the damage wrought on traditional small shops by the rise of huge, corporate-level department stores. Zola had modeled his giant store on Le Bon Marché, while Duvivier was able to shoot interiors for the store “Au Bonheur des Dames” in the Galerie Lafayette–much as L’Herbier had shot in the Paris Bourse over a weekend.

The story concerns Denise (Dita Parlo in her first French film), a naive young woman who comes to Paris expecting to work and live in her uncle’s custom-tailor shop. Instead she finds him on the verge of ruin, since the new department store is located directly across the street. He refuses to sell to Mouret, who runs the department store and wants to expand. But all the shop-owners on the block have given up, and the demolition work removing them gradually drives the tailor mad. In the meantime Denise, fascinated despite herself with the glamor of the department store, gets a job as a model there. She attracts the romantic attention of Mouret and the lecherous attention of a manager and would-be rapist (see respectively in the center and right foreground in the frame above).

Also like L’Argent, Duvivier’s film has strong elements of the Impressionist movement, which was largely over by the late 1920s. The opening portrays Denise’s reaction to the bustle of Paris after she arrives by train by a rapid montage images superimposed around her bewildered face. Later, her uncle’s growing obsession with the demolition of his neighborhood is suggested by many subjective devices, including a prismatic shot of the workers.

There are also many shots staged in depth, including a cut between Denise’s cousin’s fiancé, who has been caught sneaking out to desert her, and a reverse angle (maintaining screen direction) from behind her as he looks guiltily back.

The film was made in both sound and silent versions. Only the latter survives. I watched the Arte Video/Lobster Films version, still in print. (A Facets release in the US is out of print.) The French DVD has English subtitles, as well as a short, informative video introduction by Serge Bromberg in lieu of program notes.

The lingering legacy of World War I

During World War I, the relatively small number of films about the war naturally supported the combat, demonized the enemy, and in the US, urged people to buy War Bonds.

Given the pointlessness and widespread death and injury caused by the war, a reaction soon occurred in filmmaking within the major countries involved. Abel Gance’s J’Accuse (1919) is the earliest film displaying a bitterness about the needless bloodshed of the war, followed soon by Rex Ingram’s adaptation of Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s 1918 bestseller, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The film made it onto my 1921 ten-best list. There the emphasis shifts to family members and friends of different nationalities having to fight each other (a theme that Griffith had used in The Birth of a Nation). Four Horsemen ended with progressively distant views revealing an enormous cemetery of white wooden crosses, a motif also used briefly in J’Accuse that would become common in pacifist films of the period.

The next big film was King Vidor’s The Big Parade (see my 1925 list), one of the great box-office successes of the 1920s. The filmmakers went so far as to end the film with the hero reunited with his French love, but having lost a leg in the combat. From that point, killing off some or all of the major characters became the norm of subsequent significant anti-war films. (The Big Parade does kill off the hero’s two friends-in-arms.)

The 1930s carried on the condemnation of World War I, with two of the major films on opposite sides being released in 1930. They carry on the idea introduced in The Big Parade that the ordinary soldiers fighting on the German and American sides were basically alike and could recognize each other’s humanity.

G. W. Pabst’s Westfront 1918 starts late in the war, when the German soldiers in the trenches have become thoroughly disillusioned and unspeakably weary. The first big attack on their position turns out to be friendly fire from their own artillery. (The trope of incompetent commanding officers as among the true villains in World War I–and in some case other wars–has lingered in films ever since.) One of the four German soldiers who form the group protagonist falls in love with a French barmaid in a village near the front. In the final scene, huge numbers of casualties from the latest French attack are treated at a German war hospital, with French and German patients mixed together–as the dead had been in the battle itself (see the image above).

Pabst, like other filmmakers, uses the visit home on leave as a way to emphasize the war’s impact on the home front. Karl, the most important character of the four main soldiers, returns for the first time in eighteen months only to find his wife in bed with another man. Pabst introduces the home-front section with a long line of people waiting to buy food. Karl’s mother sees him arrive but cannot greet him because after hours of waiting she had reached the front of the line.

The impressive final battle scene ends with the last of the central characters dead, and the carnage drives the lieutenant who commands them into mad raving.

The film makes a powerful statement designed to end all wars, and yet one cannot help wonder if those Germans inclined to resent the results of the Treaty of Versailles might have been inspired to a greater desire for revenge by it.

The American counterpart of Pabst’s film is Lewis Milestone’s adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front. The 1929 translation of the German novel had become a huge bestseller in the US. Producer Carl Laemmle, who was born in Germany and visited friends and family there regularly, no doubt had a personal as well as a financial incentive to acquire the rights for Universal.

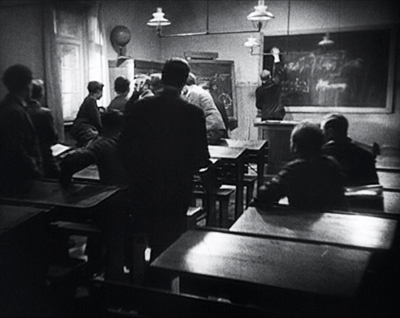

It would be easy to dismiss this big Hollywood production and ultimate Best Picture winner at the Oscars as a slick commercial venture. Certainly it has the glossy, expensive studio look that Westfront 1918 lacks, as in this scene, with its perfect three-point lighting carefully picking out each figure.

Being from a German novel, however, makes this the first significant Hollywood film to treat German soldiers sympathetically and to make them the lead characters. As in Westfront 1918, there is a tight little group of friends, three in this case, with the point-of-view figure being Paul (Lew Ayres). He is the one whom we follow on his visit home while on leave. There he visits his mother, as expected, but he also drops in on his old classroom and is disgusted to find that his teacher is glorifying war and preparing a new generation of young men to go off to become soldiers.

The opening of the film had shown Paul as a student being told of the glories of war and rushing off to sign up. This is the only one of the anti-war films I know of that portrays this sort of social indoctrination as a crucial cause of the horrors of war.

As with the other anti-war films of the 1920s and 1930s, the scenes of are extended and realistic in their depiction of trench warfare. And as in Westfront 1918, all the main characters die. At the end we see them marching off, with vast fields of white crosses superimposed.

The French produced their great anti-war films only slightly behind the Germans and Americans. Raymond Bernard’s masterful but little-known Wooden Crosses (1932), which focuses largely on French troops, is no less powerful in its depiction of trench warfare. Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1938) broke with tradition by downplaying battlefield action and focusing on the senseless loss of life and liberty and the effects of class differences in warfare.

All Quiet on the Western Front has been restored and released on Blu-ray a deluxe edition with DVD and supplements or with the supplements but no DVD.

Experimental cinema in 1930

Surprisingly enough, in a weak year for commercial feature films, there was a considerable number of significant experimental films made. The standard historical accounts when I was a grad student (and probably thereafter) suggested that sound made film production too expensive for the shoestring-budgets of experimental filmmakers. Clearly, though, many of them carried on. Some of the 1930 films are silent, but by no means all. Therefore I’ve decided to devote the tenth slot in my list to a brief summary of several of them. These are in no particular order.

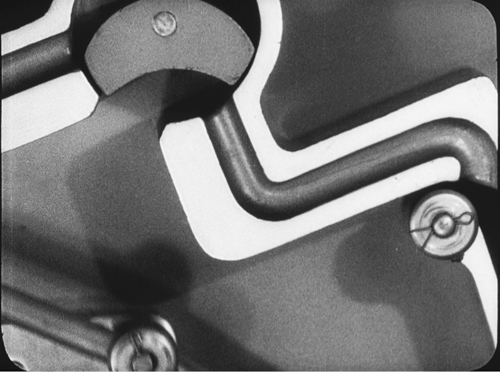

Mechanical Principles was Ralph Steiner’s next film after the better-known H2O (1929). Despite the scientific-sounding name, Mechanical Principles is an abstract film made by shooting close view of moving gears and other devices for moving parts of machines (above). The shapes and movements are engaging in themselves, but there is also, I think, a subtle and amusing progression toward more odd and even absurd-looking mechanisms. I doubt anyone would learn anything about “mechanical principles” from the film. (Included in Flicker Alley’s excellent duel Blu-ray/DVD collection, “Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970.” The visual quality is distinctly better than the versions on YouTube.)

The wonderful German animator Oskar Fischinger specialized in making abstract animation in time to pieces of music. In 1930 he made Studies No. 2 through 7. YouTube contains only snippets of his films; presumably the rights holder, the Center for Visual Music, has diligently patrolled it.) Studies No. 6 and 7 are the most widely seen. I am particularly fond of Study No. 6, to “Los Verderomes fandango,” by Jacinto Guerrero (below). These shorts use a broad range of musical accompaniment. Study No. 7 is done to Brahms’s “Hungarian Dance No. 5.” I haven’t seen all of the Studies, but I assume they all use the same technique, charcoal drawings on paper. There were VHS videotapes released and a laserdisc in 1996, all long out of print. The Center for Visual Music has brought out two DVDs with selections from his films, digitally remastered and with intriguing-sounding supplements.They are sold through the CVM.

The Bridge is a silent film, adapted from the Ambrose Bierce story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” Its director, Charles Vidor (né Karoly Vidor in Hungary, no relation to King Vidor), had come to the US in 1924 and worked as a chorus singer. He managed to self-finance The Bridge, which centers on a man condemned to execution as a spy. As he is being hanged by a military escort on a bridge, we see a complex combination of flashbacks to his childhood and fantasies of escape (below). The film was impressive enough to gain Vidor to gain an MGM contract to direct The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932). The high points of his long career are Cover Girl (1944) and Gilda (1946).

The Bridge is included on the fourth disc in the “Unseen Cinema” collection.

Walther Ruttmann’s Weekend (the original title is in English) is not a exactly a film, even though its subtitle is “Ein Hörfilm von Walter [sic] Ruttmann.” That roughly translates as “a radio-film,” and it was produced by the Reichsrundfunk Gesellschaft (national radio). On the DVD it is reproduced as a black screen with sound over, which one could play in projection. The list of sections given at the beginning runs: “Jazz der Arbeit / Feierabend / Fahrt ins Freie / Pastorale / Wiederbeginn der Arbeit / Jazz der Arbeit” (Jazz of Work / Quitting time / Travel in the Open Air / Pastorale / Recommencing Work / Jazz of Work). The “film” is a lively and often amusing montage of sounds, including trains, tools, engines starting, drum beats, brief snatches of dialogue, a cuckoo clock, a siren, a rooster, and so on. Its twelve-minute length is well gauged to avoid having the device wear out its welcome.

I hardly need to write anything about Dziga Vertov’s Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass. For many years Vertov held his high reputation largely on the basis of Man with a Movie Camera, one of last year’s top ten. Enthusiasm was Vertov’s last Ukrainian film and apparently the first Ukrainian sound feature. Although the film’s credits emphasize that it was shot on location, including the interior of a coal mine, clearly nearly all the footage was shot silent and had a “symphony” of sounds woven together and laid over it.

The film has some of the playfulness and experimental cinematography so familiar from Man with a Movie Camera. That film is so engaging in part because it was primarily a lively look at Soviet everyday life, including movie-going. Enthusiasm, however, is far more overtly propagandistic, being largely a celebration of the early achievement of the First Five Year Plan’s coal quota in the Ukraine in four years. This was thanks to the “enthusiasts,” as the film puts it: Stakhanovites, that is, workers who did considerably more than their comrades through hard labor and efficiency. (They were named after Alexei Stakhanov, a coal miner; the movement started in the coal industry.) Some of the Soviet workers and peasants sincerely approached their work in this way, but in reality much of the achievements of the Plan were achieved through forced labor.

The restored film is included on Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray disc, “Dziga Vertov: The Man with the Movie Camera and Other Newly Restored Works.”

One of the finest experimental films of 1930 is Lázló Moholy-Nagy’s Ein Lichtspiel: Schwartz Weiss Grau (“A light play [i.e., a film]: Black White Gray”). It is derived from his constructive sculpture, Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne (“Light device for an electric stage”), which consists of many metal elements, some of them pierced with rows of holes, through which lights can be shown to create moving shadows. It later came to be known as the Light-Space Modulator. (The original is in the Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard.)

Moholy-Nagy made a film of the Modulator in action, with shifting solid shapes and shadows. It is sometimes hard to tell whether the camera or the device itself itself is moving.

Unfortunately no high-quality print seems to be available. Facets offers several of Moholy-Nagy’s films on separate DVDs, including Ein Lichtspiel–which is a little odd, given that it is only six and a half minutes long. (The modern soundtrack makes the object seem like a very elaborate set of wind chimes.) This DVD is probably the source of some of the better versions of the film posted on YouTube. It would be a pity to encounter the film in this way, but given the current situation, this is the best of the copies available there.

Kenneth MacPherson was co-founder of the Swiss-based Pool-Group, along with his wife, Bryher (née Annie Winifred Ellerman) and the poet, HD (Hilda Doolittle). Together they started Close-up, an important journal on international art and experimental cinema (1927-33). MacPherson made a few films, most notably the short silent feature Borderline. MacPherson was influenced by French Impressionism and Soviet Montage, and their stylistic traits are used in Borderline, including subjective camerawork and bursts of very rapid editing to convey violence or psychological stress.

The plot deals with racial and sexual tensions in a small Swiss village when a black couple comes to live there. Pete, in a genial performance by Paul Robeson, takes back his fiancée (or wife?) after she has had an affair with a white man, Thorne. Thorne remains obsessed with her, which gradually drives his neurotic, racist wife, Astrid (HD, credited as Helga Doorn) mad. Although Thorne has rented a room over a tavern owned by people sympathetic to the black couple, the scandal leads the villages to demand that Thorne be evicted, and he leaves town.

Some other experimental films made in 1930 that I didn’t think were as good as these but are still worth watching if one is particularly interested in this genre:

Francis Bruguière’s Light Rhythms (on the third disc of the Unseen Cinema set), a more low-budget attempt at something like Ein Lichtspiel, using paper cut-outs.

Luis Buñuel’s L’Âge d’or. (The BFI Blu-ray/DVD combo is out of print, although amazon.com is still selling it. Kino Lorber put out a DVD, which I haven’t seen.) I know this is considered a wonderful film by many, but I dislike it and much prefer Un chien andalou.

James Sibley Watson’s Tomatos Another Day (on Kino International’s “Avant-garde 3” set) is a pretty dreadful film, a sort of “theater of the absurd” before its time. I suspect it is a parody of a modernist play of the day. If so, and if anyone knows what play it was, please message me on Facebook and I’ll add that information. Suffice it to say that the husband, his wife, and her lover say obvious things out loud and very slowly “You are my lover,” “I am alone,” that sort of thing. Then all three start talking in dreadful puns (“Tomotos’ another day”). One might say it’s so bad, it’s good.

Sergei Eisenstein and Grigory Alexandrov co-directed Romance sentimentale, a quite uncharacteristic imitation of French Impression or city symphonies. Finally getting a chance to see it decades ago was one of the great disappointments of my life. It is available as a supplement on the Kino DVD of the restored Qué viva México.

A succinct account of Tobis-Klangfilm’s business operations can be found in Douglas Gomery’s “Tri-Ergon, Tobis-Klangfilm, and the Coming of Sound,” Cinema Journal 16, 1 (August 1976): 51-61. (Available on JSTOR.)

I have summarized the “wooden crosses” motif that is almost universal in anti-war films of the 1920s and 1930s (and occasional later films as well) in my video essay on Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses on The Criterion Channel, where the film is permanently streaming.

Our friend and colleague Vance Kepley published an excellent study, In the Service of the State: The Films of Alexander Dovzhenko (University of Wisconsin Press, 1986).

January 27, 2021: Thanks to Cindy Keefer of the Center for Visual Music for kindly sending some corrections to my discussion of Oskar Fischinger:

All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

Vancouver: “It’s the Arts”

Frida Kahlo (2020)

Kristin here:

I wonder how many of my readers will recognize the source of this entry’s title. Is Monty Python’s Flying Circus still the perennial classic it was among young people for decades after its original series was broadcast? That brief sentence was the title of the sixth episode of the first season, shown in 1969, though I didn’t see it until some years later. The episode itself has little to do with the arts, but for some reason that particular title stuck with David and me, as few if any others did. Whenever we have encountered a TV program or a review, often something pretentious, one of us will turn to the other, or both simultaneously, and say, “It’s the Arts!”

The Vancouver International Film Festival has an admirable custom of showing many documentaries. They often deal with ecological issues and Canadian subject matter. One prominent thread, however, is documentaries about the arts. These are known as MAD, or “Music, Art and Design.” Although, as I mentioned in my previous entry, I tend to stick to the Panorama program of international fiction films, I always try to attend a few of these arts documentaries when they fit in with my interests. Most of these are in fact wonderful, not pretentious. Still, I am too accustomed to the phrase, and I think automatically, “It’s the Arts.”

Paris Calligrammes (2019)

One documentary that I was keen to see is Ulrike Ottinger’s autobiographical account of her years living in Paris during the 1960s. Ottinger is known, at least in the US, primarily for her experimental fiction films, like Freak Orlando (1981) and Joan of Arc of Mongolia (1989). I had not encountered her work since then and was eager to catch up with her at this year’s festival.

Ottinger did what many young people think of doing but never carry through on. She left home at the tender age of twenty for an exciting new life. In 1962, she moved from Germany to Paris, where she lived until 1969 before returning to West Germany. In France she lived among Bohemians and stayed long enough to witness the protests of May, 1968.

Naturally she was hugely influenced by her experiences. She tells of encountering artists and ideas: “In my euphoria, I wanted to convert all my experiences directly into art.” But how? Early on, she muses on how to convey those experiences of decades ago:

I ask myself that same question over fifty years later. How can I make a film from the perspective of a very young artist I remember, with the experience of the older artist I am today? In Paris, I followed in the footsteps of my heroines and heroes. Wherever I found them, they will appear in this film.

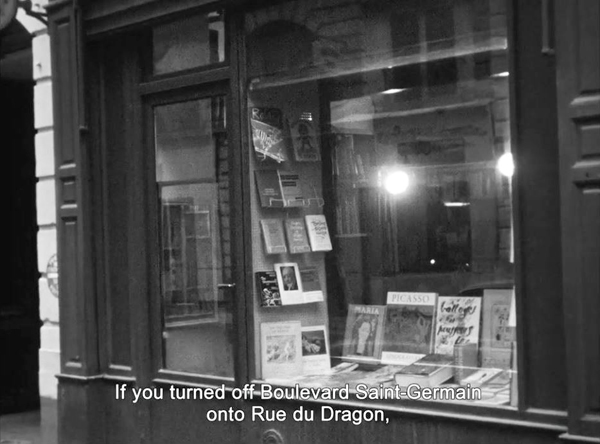

There is no footage of Ottinger from this period, and relatively few relevant photographs. Instead she wisely organizes the early portions of the film around her connection to an extraordinary bookshop that was a center of artistic and intellectual life at the time: Calligrammes (above), founded in 1951 by Fritz Picard, who had fled Nazi Germany in 1938. As a dealer in rare German and other books on the arts, Picard became host to innumerable avant-garde artists and intellectuals. Ottinger recalls buying many books on the German Expressionists and other avant-garde artists and movements of earlier decades.

(David bought some books for his dissertation on French Impressionist cinema at Calligrammes in the summer of 1973. Picard died in November of that year, though the shop was continued for a time by others.)

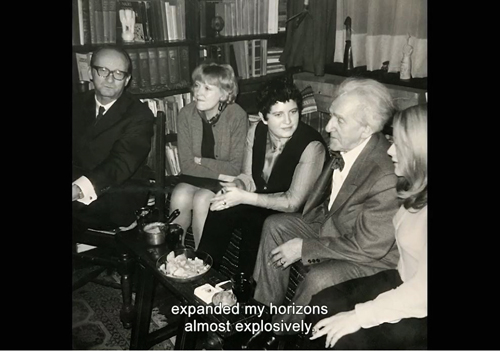

Ottinger became a friend of Picard and socialized with the patrons and visitors of the shop. Below, she’s in the black vest, sitting beside Picard at a party. She also was indirectly influenced by the great artists of the past, such as Hans Richter, who had frequented Calligrammes. In one sequence she flips through the guest-book signed by many a famous visitor, and we see clips from films like Ghosts before Breakfast, which influenced her.

Following this section, Ottinger gives us sequences on the effects of the Algierian war on her friends in Paris and describes the protests of May, 1968, some of which she was able to see from her apartment near the Sorbonne.

Perhaps inevitably, Paris Calligrammes reminded me of some of the Agnès Varda’s late autobiographical work. Ottinger is less lyrical and personal, as well as being more overtly political. There is more of a sense of name-dropping, at least in the early section. Still, who wouldn’t be interested in hearing about the early life of someone who has had such adventures? Ottinger also describes the influences on her by the artists she learned about and met. The brief clips from her own films should inspire a new generation of film buffs to seek out her work.

Like so many of the films at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year, Paris Calligrammes was shown in Berlin. For an enthusiastic and informative review done at the time, see Richard Brody’s piece in The New Yorker.

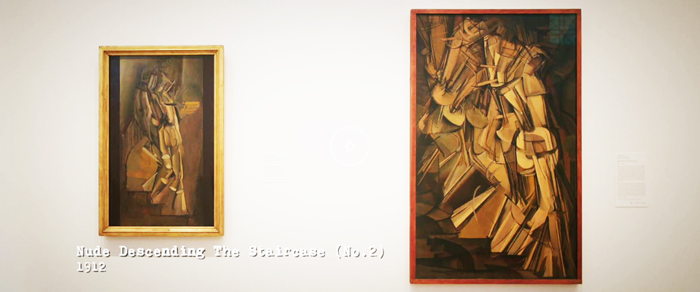

Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible (2020)

I am of two minds about Matthew Taylor’s documentary on Duchamp. It presents an excellent overview of the artist’s career and work, and one could learn a great deal from it. It makes clear, for example, the relationship between Duchamp’s early ready-mades and the fact that they were mostly subsequently lost and much later replaced by replicas–all with the artist’s cooperation. It puts his important early painting “Nude Descending a Staircase” (see bottom) in its historical context.

There are the usual experts explaining Duchamp’s intellectual approach to his artworks and his considerable influence on subsequent generations. We are not given much indication concerning who some of these experts are. The identifying labels often just say “Curator” or “Art historian” without linking the experts to any institution or publication. I tried looking one of them up on the internet and couldn’t find him. I’m sure, however, that they know Duchamp’s life and work well.

These experts are also almost all extremely enthusiastic about Duchamp’s work and especially the impact he has had upon art–not, as they emphasize, just specific trends but absolutely all subsequent art up to the present. Early on in the film, before we have been introduced to most of the talking heads, a voiceover declares, “Without him, imagine where we would be. We’d be painting in the style of Matisse or Picasso. That’s what modern art would be without Duchamp.”

(Ironic note: Duchamp’s stepson, Paul Matisse, is the grandson of Henri Matisse.)

That’s a pretty remarkable claim. It’s hard to think of a period that long in the post-Medieval era when art has just frozen in place for a century. Surely innovative styles and individual artists would have come along and produced distinctive work that did not depend on Duchamp’s main claim to fame, his demonstration that anything could become an artwork if we regard it as such. Did the Soviet Constructivists depend on Duchamp’s idea? Did the German Expressionists? Do highly individualistic artists? (See the section below.) Do manga and graphic novels, which are coming to be thought of as worthy of attention as art–not just because someone found them and declared them so, but because they contains qualities that were considered artistic well before Duchamp?

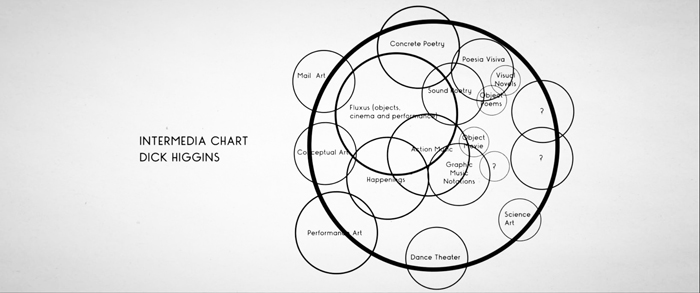

To be sure, Duchamp did have a huge impact, as this chart, shown in the film, suggests. It was devised by Dick Higgins, artist and co-founder of Fluxus. (The absence of Pop Art among the circles is rather puzzling, though it does figure in the film.) One could, however, devise many other circles for trends and institutions that do not reflect that impact.

Toward the end of the film, the experts go further, suggesting that Duchamp encourages the democratization of art by suggesting that anyone can be an artist, whether on their own or by taking and re-purposing existing artworks or objects or sounds. Yet would we say that the many outsider artists of the past century who have come to the recent attention of taste-makers had anything to do with Duchamp? And fanart, if that is included in this vast generalization, existed before Duchamp.

Despite the obvious excitement the experts display in extolling Duchamp’s work, someone watching the film might be less sympathetic, given the debatable state into which Postmodernism in general has led the art world. As one inevitably thinks, what’s next, Post-Postmodernism?

Duchamp himself seems, according to the film, to have had considerably less enthusiasm about his own artworks, preferring perhaps the idea of them rather than the execution. He took twelve years to complete the Great Glass and declared himself pleased with the results when an accident severely cracked its surface. He did not bother to keep track of his ready-mades, most of which disappeared. One wonders why he bothered to follow the initial venture into that area with “Fountain” (a urinal signed “R. Mutt 1911”), since subsequent ready-mades like “Hat Rack” (above) make the same intellectual point.

Late in life Duchamp seemingly gave up art-making to devote himself to competitive chess. After his death it turned out that from 1946 to 1966 he had been working on “Étant donnés,” a peep-show view of a spreadeagled nude woman, based on his mistress during part of that time. Despite the raptures expressed by the experts, it looks like it could be considered revenge porn. But only, presumably, if one calls it that.

Only one of the experts, Peter Goulds, departs from the general unquestioning idolization of Duchamp. Near the end he says,

Later in life, of course, he must have found it incredibly amusing to hear people latch onto his theories as though they were universal truths, when actually his whole life was about bucking those very conventions and defying them. So I’d like to suggest that his form of so-called conceptual art was a much more playful exchange. I’m not so sure about how even serious he was about it himself. Here he throws these things out as suggestions, with thought. Others, perhaps more needy than himself, would make these rules be therefore solely applicable.

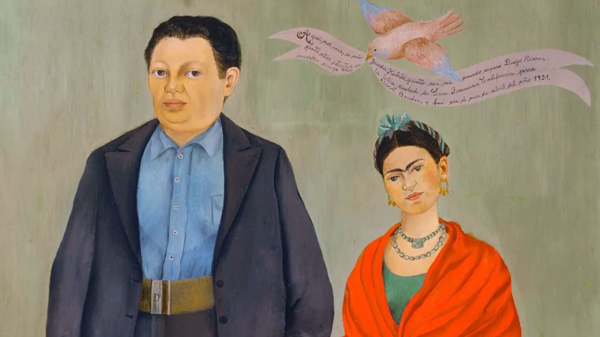

Frida Kahlo (2020)

Frida Kahlo is one of those artists who don’t appear to owe much, if anything to the influence of Marcel Duchamp. As the film makes clear from the start, she was aware of European artistic movements and developments. Still, neither she nor her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, seem to have absorbed much from them. Kahlo always denied that her later work was Surrealistic, and one might rather attribute its fantastical elements derive more from the Latin American tradition of Magical Realism.

Indeed, the whole idea that Duchamp influenced all of modern art comes to seem remarkably Amero- and Euro-centric if one considers that it implicitly either scoops highly individual artists like Kahlo up into one enormous category or eliminates them from that category altogether.

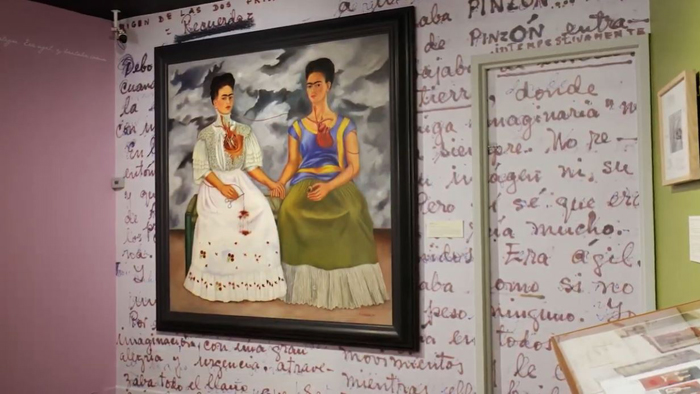

I found Frida Kahlo more satisfying than Marcel Duchamp. Its experts are all clearly identified as to their position and institution. Some are curators of the institutions which own her works, such as the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. There “The Two Fridas” is shown (see top) as the curator discusses it.

These experts are as enthusiastic about their subject as those in the Duchamp film, but they are focused entirely on recounting Kahlo’s life, her social context, and the influences on and changes in her style across her life. For example the simple presentation of “Frida and Diego Rivera,” an early portrait done shortly after their marriage, gives way to the more sophisticated and symbolic “The Two Fridas.”

Archival photographs and film clips illustrate the eras of the places where Kahlo lived and traveled. The impact of the lingering effects of her injuries in an extremely serious traffic accident in her youth, her travels with Rivera in the US, and the rockiness of their marriage are all discussed to help clarify the often cryptic visual references in her paintings.

In short, Frida Kahlo is a model of a staightforward and informative documentary on an artist. I was pleased to be introduced by it to its producers, Exhibition on Screen. In business since 2011, it has made twenty-six such documentaries. These are shown in theaters and festivals initially, before being made available on disc and streaming on their website. Frida Kahlo is promised for streaming on October 20.

Once again, thanks, as usual to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible (2020)

Vancouver: First sightings

Big Tech as Pac-Man: The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

DB here:

Every festival has had to adjust to COVID-19. This year the venerated Vancover International Film Festival continues with some in-person events at the VIFF Centre and the Cinematheque, but most of the screenings are done remotely. The streaming resource is available only in British Columbia and is a wonderful option for regional cinephiles.

Over the next two weeks, we’ll continue our annual tradition of covering some of the outstanding films mounted by this superb festival. As usual, we hope to guide local viewers while the event is in progress and to signal readers about upcoming releases in their territories.

Deep dives

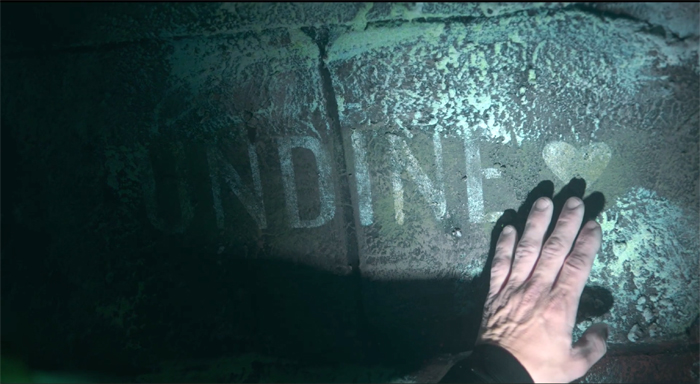

Undine (2020).

No lyrical drone vistas, no establishing shot, no title telling us where and when we are, no voice-over trying to lure us in. Just bam, here it is, deal with it. Any movie that starts with a reaction shot in OTS (over the shoulder) of a fiercely downcast woman gets points automatically. The fact that she goes on to threaten to kill the man she’s talking to is just a bonus.

That threat, made by the protagonist of Christian Petzold’s Undine, is about the only hint that she’s capable of homicide. She seems otherwise a well-adjusted young woman free-lancing as a guide in Berlin’s Urban Development Center. As in other Petzold films, thriller conventions are invoked but suspended while a deepening personal drama emerges. At first, we tag along with Undine in her rebound-affair with Christophe, an engineer specializing in repairing underwater equipment. All is going well enough, but there are signs of trouble, particularly a near-death experience in a lake. Then, after the midpoint, tension ratchets up with two quick twists that put new pressure on Undine to take violent action.

Sorry to be so oblique, but this is one of those movies with a real plot, and since it’s eventually coming to the US, I’m avoiding spoilers. Admittedly, the last twenty minutes take off into new territory, and I found myself unable to know what to expect next. (It’s one of those movies that seems to end several times. That is often a good thing.) But the unruffled precision of Petzold’s direction, the thriftily paid-out backstory, and his gift for suspenseful storytelling mitigate the quasi-supernatural tint of the twists. I tend to see them as GOFAC (Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema), ambiguous moments that may flow from the characters’ imaginations.

An undine is a water nymph, the heroine’s lover is a diver, her job is to lecture on the rebuilding of Berlin over the years, and his job is to explore a submerged city (which hosts a slab bearing her name). All this was for me a reminder that ambitious directors can invest genre conventions with poetic lyricism. Admirers of Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and Transit (2018) will need no urging to visit a film I found completely absorbing.

A film from two billion years from now

Last and First Men (2020).

On the visual level, Jóhann Jóhannsson’s Last and First Men is a good example of what we call “abstract form” in our book Film Art. The filmmaker builds a film out of patterns of sensuous visual qualities. Everyday objects can yield these qualities (our example is Ballet Mécanique), but abstract form can also be found in unusual, even unidentifiable sources.

That’s what we get here. The shots reveal structures and textures in immense, brutal constructions of metal, stone, and cement. Are they sculptures? Totems of some bizarre religion? Remnants of blasted modernist buildings? Fragments of space ships crashed to earth? The moving camera reveals their shapes, textures, and off-kilter strains for symmetry. You lose all sense of scale: these might be the size of dinner tables or tabernacles. Most are set against the sky, alternately misty or searingly bright.

No story connects our views of these strange monuments. On the soundtrack, though, a woman’s voice recounts the history of the future. After two billion years, the narrator represents the “eighteenth species” of humans, and via telepathy she informs us of the impending end of human life on Neptune.

We never see any of those events, just the ruins calmly surveyed by the camera. Almost never does the commentary sync up with the shots. The woman’s account of future humans might at first seem to match the carved, staring blocks we see, but she goes on describe them as furry or translucent.

The disparity between description and depiction emphasizes the gap between tracks.

For most of the film, then, we have a split. The image track explores abstract, nonnarrative form. The soundtrack supplies a narrative, actually a Very Grand Narrative. The text, it’s revealed in the credits, comes from Olaf Stapledon’s 1930 science-fiction novel, Last and First Men.

There’s yet a third layer. Jóhannsson, a brilliant composer who died in 2018, gave us memorable concert music and film scores (Sicario, Arrival, The Miners’ Hymns). Along with the voice-over we hear a sometimes radiant, sometimes jarring orchestral accompaniment created by Jóhansson and electronic composer Yair Elazar Glotman. The music doesn’t cooperate much with the voice-over. As the commentary proceeds with a businesslike dryness, the music often flows and eddies on its own course.

The fact that the three channels of picture, voice, and music seldom converge actually sets your imagination free. There’s no need to see the images as illustrating the text, or the music as operatically enhancing either one. We’re allowed to keep the realms separate, or to test obscure correspondences. We can, for instance, see the expressive qualities of the shots as enduring remnants of human will–eccentric, obstinate, and obscure as it can be. The music’s alternation of drone passages, scraps of choral lyricism, and ominous rumbles might seem to chart humans’ up-and-down fate in the late Anthropocene. The narration, recited by Tilda Swinton, adds a quality of stoic dignity to the mix. And you’re invited to try out metaphors, as when cavities in what seems to be an elongated cathedral suggest eyeholes for staring across space.

The disparity of channels is enhanced by another mystery I haven’t seen mentioned in reviews. The images betray their origins on 16mm film. There are light leaks on the frame edges, specks of white suggesting dust on the negative, and even bits of grit and hair in the aperture. Perhaps you can see the hair snagged in the upper right of the image below.

These flaws have not been digitally removed. Indeed, the film’s opening moments linger on black frames flecked with white dust, priming us to watch for faults in these images.

The effect is to add an archaic quality, as if this is all found footage from long before the end recounted on the soundtrack. Since the narrator tells us that humankind goes through many near-extinctions until the big one, these relics may be from one of those future collapses–or, perhaps, from our own past, remnants of a calamity we’ve forgotten. The text speaks of “the debased rites of your religions long ago,” and those big-eyed humanoids are reminiscent of Australian aboriginal art.

In all, it’s a bleakly beautiful experiment. The film premiered with live orchestral accompaniment in the 2017 Manchester International Festival, and it must have been hypnotic. The film and soundtrack are now available on a CD/Blu-ray combination, as well as on vinyl.

Meet the New New Boss, same as the Old New Boss

The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

The scathing 2003 documentary The Corporation took seriously the idea that corporations were persons. Their behavior, considered clinically, is that of a sociopath. Now Joel Bakan and Jennifer Abbott’s followup shows how the 2008 financial crisis provoked corporations to rehabilitate. Hip CEOs admit the existence of racial bigotry, income inequality and the failures of conservative government. The solution? More corporate power. Did this make them any less dangerous?

Nope. Multinationals shape government policy as vigorously as ever, especially in the era of Trump and other demagogues. But the corporations’ new message is soft power. Posing as socially committed, emphasizing stakeholders as well as shareholders, Big Business is (a) trying to convince consumers that it’s on their side; and (b) arguing that the New Corporation will correct the shortcomings of government policy through privatization. In other words: We’ve learned our lesson. We get it. So let us run things. Besides, what choice do you have?

Bakan and Abbott shrewdly show that this ploy neatly fits an updated clinical symptom of the sociopath: “Use of seduction, charm, glibness, or ingratiation to achieve one’s ends.”

The film begins with a fascinating visit to the Davos Forum, where air-kissing one-percenters solemnly assure us that everybody wins when a corporation acknowledges the public good. The star player is Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase. Having helped crush American cities in the financial crisis (and paying a derisory $13 billion fine), he is now playing rescuer by supporting the rebuilding of Detroit, to the benefit of his company’s image. The film goes on to trace how the public face of caring executives is belied by business as usual, most savagely British Petroleum’s catastrophes in Texas City and at Deep Water Horizon.

Bakan and Abbott marshall a great deal of evidence to show how the plutocracy, and especially those in the digital technology sector, have turned a market economy into a market society. For us, the role of worker-consumer redefines the other dimensions of civic life. You work without union protections and scramble to keep up. You give your personal information to Facebook, Google, and Amazon in exchange for convenience and lower costs. (The old adage holds: If something is free, the product is you.) Schools, postal delivery, war, water, and relationships are all ripe to be rendered as private enterprise. With AI algorithms, the customer-customized milieu of Minority Report is already here.

Talking heads, from Chomsky and Robert Reich to Diane Ravitch and Vandana Shiva, offer pithy critiques, and footage garnered from around the world illuminates each of the points in the Corporate Playbook. As a counterweight, later portions of The New Corporation show some pushback. Katie Porter poleaxes Mr. Dimon in a House hearing, and we glimpse AOC in her usual passionate eloquence. Still, the emphasis falls less on pols and more on citizens who struggle against corporate power.

Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders campaign are shown to be as important to the left as the Tea Party was to the right. The filmmakers give special attention to the efforts of many tough, idealistic people to run for public office. As one commenter puts it, “Even in the worst situations, people always fight.” In a remarkable passage, a dopy prankster from The Corporation is shown to have become a proud progressive after seeing the first film and joining the Sanders campaign.

The film is startlingly up-to-date, incorporating events around the George Floyd atrocity and the Black Lives Matter street actions. Some will say that the late sections drift a bit from the film’s core message of analyzing the fake social concerns of the New Corporation. But income inequality and environmental destruction, central drivers of new social movements, are invoked in corporate PR as vital concerns for companies’ new image, so the final sequences don’t seem to me tacked on. They show what real social engagement, as opposed to panting coverage in Forbes, looks like.

Where do you start? someone asks in Tout va bien. The answer: Everywhere at once. I think The New Corporation indicates that this might just work.

The three films I’ve discussed are exemplary of the strengths that have characterized the Vancouver festival for its 39 years. Here you can plunge into international auteur cinema, unusual experimental work, and documentaries committed to our noblest aspirations. Programmers Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, and their colleagues scour the world for provocative films, and the results have taught Kristin and me lessons about cinema we wouldn’t have learned otherwise. It’s worth noting that VIFF’s welcome to Canadian cinema has always been fruitful: The New Corporation, like its predecessor, is a British Columbia production and is featured in the festival’s ongoing True North series.

Fourteen years ago I wrote that Vancouver was the very model of a regional festival, at once deeply local and unpretentiously cosmopolitan. It still is. Take that, corornavirus! Nothing stops dedicated film lovers.

Thanks to Alan Franey, Jane Harrison, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

A sensitive review of Undine is offered by David Hudson at the Criterion Daily.

A note on Last and First Men: In watching the film, I found myself constantly asking if these structures really existed, or whether they were CGI creations or miniatures or objects purpose-built for the film. Some reviews have revealed their secret identity, and knowing what they are does raise some interesting thematic implications. But I’m refraining from telling you because I think your first encounter with the film ought to include that mystery about what exactly you are seeing. If you want to know what they are, Google is at your service. There’s also this spoiler-filled behind-the-scenes video.

Jennifer Abbott has another documentary in this year’s festival: The Magnitude of All Things. I look forward to it.

Undine (2020).