Archive for the 'Film scholarship' Category

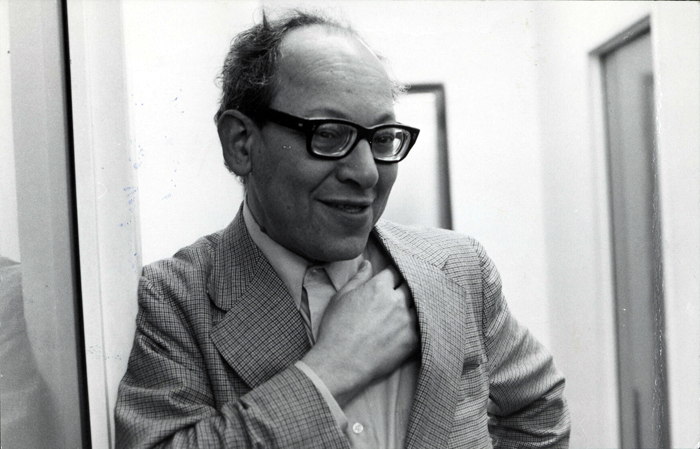

Jacques Ledoux, man of the cinema

Jacques Ledoux.

DB here:

Jacques Ledoux, one of the world’s premiere film archivists, died in 1988, but his example and influence live on. An insatiable cinéphile, a friend to filmmakers around the world, and a tireless collector of films for the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, Ledoux did not have the celebrity status of Henri Langlois. Quietly and modestly, he went about the task of building one of the great film libraries and launching traditions that outlived him. He was at the center of Belgian film culture, which was as cosmopolitan as any you would find in bigger European or American cities.

Central examples of his enterprise: EXPRMNTL, the Knokke-le-Zout experimental film festival; the annual Cinédécouvertes summer festival showcasing films of exceptional ambition that had not yet found a local distributor; and the L’Age d’or prize for films challenging “cinematic conformism.” Martin Scorsese’s The Big Shave (1967) had its premiere at Knokke, where it won the Prix L’Âge d’or. The first winner, in 1955, was Agnès Varda for La Pointe Courte; later winners read like a roster of great directors. The impulse continues to this day. In addition, Ledoux established a distribution branch that allowed student groups and film clubs to borrow prints for their screenings.

There were always obscure legends about his past. “Jacques Ledoux”–“Jacques the Gentle”–was a name he took late in life. Eventually we learned that as a boy he survived the Holocaust by jumping off a train shipping him to Auschwitz. By the end of the 1940s he was participating in the Archive’s activities and he eventually became the director.

Ledoux set about creating a vast showcase of world cinema. Five screenings, two of them silent films, ran every day of the year. Admission prices were low, to permit students to come. At the same time, Ledoux oversaw collections of film technology that formed the basis of educational exhibits. The Archive became the center of the city’s film activities.

Ledoux was a passionate collector, amassing films from far outside Belgium. He was curious about all types of cinema, mass-market and esoteric. When the Nouvelle Vague directors wanted to see a film banned in France, they took the train to Brussels and Ledoux’s domain. The same urge for comprehensiveness informed his efforts to document film history, with filmographies and background information in books published by the Archive. He became a moving spirit of FIAF, the International Association of Film Archives; here you can read about his many accomplishments in that area, as well as his eventual friction with the organization.

His generosity extended to young researchers like Kristin and me, who were welcomed to study films at the Archive. That became the basis of our lifelong friendships with Archive staff and many Belgian cinéphiles, as sometimes chronicled in our blog entries. So grateful was I for Ledoux’s assistance that when I was offered a professorship at my university, I gave it his name. He had just died, and he probably would have protested that he wasn’t worthy; but he has remained an inspiration to us for over forty years.

His generosity extended to young researchers like Kristin and me, who were welcomed to study films at the Archive. That became the basis of our lifelong friendships with Archive staff and many Belgian cinéphiles, as sometimes chronicled in our blog entries. So grateful was I for Ledoux’s assistance that when I was offered a professorship at my university, I gave it his name. He had just died, and he probably would have protested that he wasn’t worthy; but he has remained an inspiration to us for over forty years.

The Archive, now calling itself the Cinematek, has just finished a centenary exhibition devoted to Ledoux. Christophe Piette, organizer of the event, has memorialized it in a lovely multilingual book that gathers reminiscences by Ledoux’s colleagues. There are memoirs by Noël Desmet, Clementine Deblieck, Jean-Paul Dorchain, Hilde Delabie, and Gabrielle Claes, Ledoux’s successor as director. Bernard Eisenschitz, Eric De Kuyper, and P. Adams Sitney offer illuminating appreciations of Ledoux’s contributions. (Sitney’s very full account of Knokke doings is a crucial document in the history of the American avant-garde.) Ledoux’s own voice is represented by a program note for a 1968 science-fiction series. There are many wonderful illustrations–photos, posters, correspondence (Cocteau, Lenica, Akerman). Kristin and I have provided recollections of a man we immensely admired. When you read one of our blog entries on older films, classic or little-known, chances are good that we first saw the film at the Cinematek.

The book is published in a limited edition but is available for purchase at https://cinematek.myshopify.com/en/collections/boeken/products/jacques-ledoux. Every university library with a substantial collection of film literature should acquire a copy!

Anke Brouwers has written a vivid overview of Ledoux’s career for the exposition. Many nifty documents are illustrated.

There are too many citations of Ledoux and the Archive on our site for me to list them. Two extensive ones are “Ledoux’s Legacy” and “Watching movies very, very slowly.” For others, you could try the Search function (using “Brussels”) to find accounts of our many visits.

When media become manageable: Streaming, film research, and the Celestial Multiplex

Never coming to the Celestial Multiplex: Liberty Belles (Del Henderson, 1916).

DB here:

A directors’ roundtable in The Hollywood Reporter says a lot in a little.

Fernando Meirelles: This June, The Two Popes was in 35 festivals. Then we were going to have two or three weeks of theaters. And then the [Netflix] platform. I mean, it couldn’t be better.

Martin Scorsese: We are in more than an evolution. We are in a revolution of communication and cinema or movies or whatever you want to call it.

Meirelles casually omits DVDs, at one point the most rapidly adopted format of consumer media. Yeah, what ever happened to discs? And in what follows, I’ll take issue with Scorsese’s claim that streaming has triggered a revolution. It’s more a case of evolution that issued in a sweeping change, like Engels’ transformation of quantity into quality, or Hemingway’s claim that he went broke slowly, then quickly.

More important, I’ll try to assess the impact streaming has had on what Kristin and I and other researchers and teachers try to do–study film as an art form in its historical dimensions.

Managing your time, and your movies

If we’re looking for a revolutionary turning point, I’d suggest the moment that movies no longer became appointment viewing. When they played theaters you had limited access. The film was there for only a while (even The Sound of Music eventually left) and you had to watch it at specified times. On broadcast TV and cable, the same conditions applied. But with the arrival of consumer home videotape in the 1970s, the viewer was given greater control.

Akio Morita of Sony called it “time-shifting.” The phrase, shrewdly positioned as a defense of off-air copying, captures a fundamental appeal of physical media. You could watch a film at home, and whenever you wanted to. Yes, VHS and even Beta yielded shabby images and even worse sound, but (a) theatres were often not much better, and (b) a video rental was cheaper than a movie ticket. Most important was a general rule of media technology: For the mass market, convenience trumps quality.

Videotape swept the world in the 1980s and gave films an aftermarket. Many an indie filmmaker could get financing for a project on anticipated tape sales. The laserdisc gained some attention in the 1990s, becoming a sort of transitional format. It improved quality (better analog picture, digital sound) but had drawbacks too. A movie wouldn’t fit on a single disc side, and a laserdisc was pricier than tape. LD remained a niche format, chiefly for educators and home-theatre enthusiasts.

The laserdisc was superseded by the DVD, introduced in 1996. Journalists claimed that it enjoyed the fastest consumer takeup in electronics history. Discs were more convenient than tapes, and proof of concept had been provided by the success of CDs for music. To compete, cable companies introduced “video on demand,” a time-shifting compromise between scheduled cable delivery and rental of tape or disc. People still use cable VOD, and for some purposes it’s a cheaper alternative to committing to subscription services.

Reviewing The Irishman, a critic suggested that most people will skip seeing it in theatres and watch it on Netflix, where it’s “more manageable.” With tape and disc, either analog or digital, consumers became accustomed to a huge degree of manageability. They could pause, skip ahead or skip back, race fast-forward or –back, play slowly, and above all play the movie over and over. DVDs made all these options quicker and more convenient than tape had. The market boomed. Video stores made discs available for rental, as tapes had been, and retail stores offered them for sale, at increasingly low prices.

But there were problems. In the 2000s there was a glut of DVDs, and consumers began to realize that a few weeks after release many titles would end up in the bargain racks. A brisk secondary market developed thanks to the US “first sale” doctrine, most virtuosically exploited by Redbox. Worse, there was piracy. Pirating analog tapes degraded quality across generations, but with digital discs you could rip perfect clones. Any teenager could hack past region coding and anticopying software.

The Blu-ray disc was an improvement on the first-generation DVDs, and it came along as more people were buying widescreen and high-definition home monitors. Properly mastered, Blu-ray discs looked good, and they had bigger storage capacity. Some consumers got excited, but the improved format couldn’t arrest the headlong decline of disc sales. In addition, the industry’s rationale for Blu-ray was its resistance to rippng, but hackers breached the codes with ludicrous speed.

From this angle, streaming is parallel to digital theatre projection : a new phase in the war against piracy. Likewise, as in theatrical screenings, you’re paying for an experience, not an item. You’re not buying an object you can copy or resell. If a movie is available only on streaming, you’re renting something, not owning it legally. One aspect of manageability—personally possessing a movie—is traded away for convenience and, ultimately, for limited access, as I’ll try to show.

Not so gently down the stream

With streaming, the age of appointment viewing seems more or less over. And the infinite vista of the Internet has encouraged tech-heads to imagine something like the Celestial Jukebox, a vast virtual multiplex in which all movies will be available. If iTunes and Spotify did something like this for music, why not cinema?

Let’s consider the pluses and minuses of streaming for ordinary consumers and for filmmakers.

Obviously, there’s convenience. After the monstrous tape cassettes, DVDs looked adorably slim. Now, gathering in slippery stacks, they have their own sinister aura. With streaming, there’s no need to run out to the video store or to buy new shelving to support a bulging library of discs.

There’s also price, compared to either theater tickets or cable fees. From $6.99 per month (Disney+) to $12.99 (Netflix), streaming services promise to provide TV and movies quite cheaply. And there’s the range of choice, which even on second-tier streamers exceeds the capacity of most towns’ video stores back in the day. Finally, there are many obscure films lurking in the corners of most streamers, so the joy of discovery is still there to a degree.

On the minus side, there’s one that gets the most press—the further erosion of “the theatrical experience.” Critics emphasize the pleasures that come from being in an audience, but this always seems to me overrated. More valuable to me are the scale of image and sound you get in a theatre. I like my movies to loom.

Above all, there’s a virtue in the lack of manageability. In the theatre you can’t pause the movie or run back or skip ahead. You can close your eyes, look away, or leave, but at bottom you’re there to turn your sensorium over to the filmmaker, to go through an experience you don’t control. This unshakeable grip on your attention yields some of cinema’s most powerful effects.

The condition of privatized viewing isn’t unique to streaming, of course. Nor is another drawback, that of the cyclical expiration and refreshing of “content” on streaming platforms. Admittedly, we’re warned. Newspapers and websites run alerts notifying us when a title is leaving a service—perhaps for a little while, perhaps longer, perhaps forever. And this situation is a bit like DVDs’ going out of print. But at least some disc copies exist to be sold second-hand or cloned as files. In working on my book on the 1940s, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that I could track down arcane titles on out-of-print discs, and at fair prices. When something not on disc leaves streaming, how do you access it?

I think there will be some pushback when subscribers learn about the costs that more and more services are tacking on. Yes, with Amazon Prime for $119 per year you get access to many films, along with other services. But for a great many films Amazon demands an extra rental fee and very short-term access. Within Amazon, there are channels (Britbox, HBO Now, Starz, Cinemax et al.), all of which demand further subscription payments. As people start to realize that streamers will have exclusive licenses for titles, they’ll feel pressure to subscribe to many services. Here, as elsewhere, the total streaming price tag starts to look like cable fees. Even the New York Times has noticed.

Another problem won’t bother most consumers, but it does matter. A streamed title will occasionally be in an incorrect aspect ratio. Most commonly, a Scope (2.39 or so) image will be cropped to 1.85. I noted this some years back, relying on a website showing faulty Netflix transfers, but that site seems to have been taken over by … Netflix itself.

Netflix will say, with all “content providers,” that they get the best material they can from their licensors. I don’t watch streaming enough to know how common wrong aspect ratios are, but if you know of examples, I’d like to hear.

Finally, even streaming companies can collapse. Unless Apple buys a studio (Lionsgate? MGM? Columbia?), it must rely on original content, and it could well flop. On the day I’m writing this, one hedge fund manager predicts we have reached peak Netflix. Given greater competition, slower growth, and accelerating cancellations, he maintains that Netflix is on the wane. If it scales back or fails (it currently carries $12.43 billion in debt), what will happen to its licensed material and its original content?

What about creators? Filmmakers, especially screenwriters, have enjoyed boom times. It may be a bubble, with over 500 scripted series available on broadcast, cable, and streaming. Still, it has given everyone a lot of opportunities. Documentary filmmaking in particular has enjoyed a shot in the arm.

And features are still doing quite well, at least on Netflix. Of the streamer’s top 10 releases in 2019, seven were features. But those proportions may change. Aside from big theatrical movies licensed from the studios, the impact of proprietary “event” programming (War Machine, Bird Box) has been fairly ephemeral. (Obviously Roma and The Irishman are exceptions.) The strength of streaming, it seems to me, is the same thing that sustained broadcast TV: serial narratives. Hence the popularity of Friends and The Office, as well as House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black.

Like network TV, a streamer needs a reliable, constant flow of content—not only many shows, but many episodes. The model of the series, if only in six or eight parts, secures the loyalty of the viewer for the long term. Even if all episodes are dumped at once, the promise of continuation after an interval of a year or several months keeps the viewer willing to hang on till the next season.

The pressure on the creators is predictable. Since form follows format, writers and producers will be pushed to come up with series ideas. A friend of mine pitched a feature-length movie to a streaming service. The suits loved the idea but wanted it as a series and were already scanning the script outline for a plot point that could launch a second season. Some of the streaming series I’ve seen, notably Errol Morris’s Wormwood, seemed to me stretched.

If a filmmaker lands a feature film on a streaming platform, other problems could follow. We’re well aware that independent filmmakers gain few royalties from streaming; their big check tends to be the initial acquisition. At the same time, they can’t be sure that people are watching their entire movie. My barber couldn’t stick with The Irishman, even with pee breaks.

Streamers seem to have accepted grazing as basic to the viewing experience. For purposes of measuring total viewership, Netflix counts a “viewing” of a film or program as a minimum of two minutes. In the light of the two-minute rule, we might expect filmmakers to crowd their opening scenes with plenty to grab us. That goes back to TV and TV-influenced films, of course, which tried to have a strong teaser even before the credits. Now, it turns out, streaming pop songs are being crafted with shorter intros and earlier choruses “to get to the good stuff sooner.” Maybe filmmakers will be trying the same thing. Maybe they already are.

Streaming and film research

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018).

Finally, what are some consequences of streaming for researchers, educators, and your all-around obsessive cinephile?

I think it’s fair to say that home video, in the form of tape, laserdisc, and digital disc, democratized film study. From the late 1960s on, I traveled to archives and film distributors to watch films for my research. It was troublesome, time-consuming, and costly. As a grad student I took a bus from Iowa City to Chicago to watch 16mm prints of Dreyer and Sontag films. I drove to Eastman House to see films in projection. I stayed in Paris a couple of months to work at the Cinémathèque Française on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse.

As a prof here at Madison I spent hundreds of hours watching prints in our Center for Film and Theater Research. Over the decades I trekked to Denmark for Dreyer and 1910s films, to Japan for silent films, to Paris and Munich and the BFI and MoMA and UCLA and Eastman House and the Library of Congress, and above all Brussels for many, many projects. Collectors, from Manhattan, Tokyo, and Milwaukee helped as well. Kristin and I owe archivists everything.

The terrible quality of films on tape didn’t help me study visual style, but laserdiscs were a big improvement. (Hong Kong films tended not to be in Scope on tape but were on LD.) And one LD format, CAV, was frame-accurate; you could study a shot frame by frame, something not possible with many DVDs. There’s always a trade-off with any technology.

Even after even after DVDs arrived I kept up my travels. I could use discs for bulk background viewing, but often I still had to rely on prints. Sometimes I wanted to count frames (handy in looking at Soviet montage and Hong Kong action). Moreover, looking at film prints revealed that the color palettes on DVDs could be quite different, and soundtracks were often cleaned up for the home market. And of course thousands of films, especially from outside Hollywood or in the first decades of cinema, were never going to be available on consumer video. My most recent extended archive stay, in Washington in 2017 thanks to a Kluge Professorship, showed me the glories of the 1910s in prints that are mostly accessible only to researchers.

What do scholars of an analytical bent need? Entire films that can be paused. Frame stills, made photographically or through software. Clips as evidence for our claims. Stills and clips are our equivalents to quotation for literary scholars and illustrations for art historians.

Apart from convenience and cost savings, the disc revolution yielded something I couldn’t get otherwise. In an archive, it’s impossible to study film-based 3D cinema. But thanks to Blu-ray, I can stop on a 3D frame. (. . . And, for instance, spot the way Hitchcock makes the clock quietly pop out in Dial M for Murder, below). This is a unique benefit—but a waning one, as 3D discs are increasingly hard to find and 3D monitors scarcely exist any more. As I said, trade-offs.

From this standpoint, Netflix and its counterparts offer a step down from DVD and Blu-ray. In terms of choice, many films aren’t currently available on streaming, and many more never will be. You can pull a DVD off a shelf whether you’re online or not, but for streaming you need a good connection. The controls of a streaming view aren’t as precise as those on a DVD player; slow forward and back to study cuts and gestures aren’t feasible, it seems.

When cable cropped films, as it frequently did, you had recourse to DVDs, perhaps even from foreign sources. But as exclusive licensing increases, only one service will have a title. Frame grabs are possible with some software, but clips are more difficult.

Worst of all, many worthwhile films will apparently never find their way to disc. I first noticed this in 2017 when I wanted to buy a copy of I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, a Netflix release of a Sundance title. As far as I can tell, it’s not available on DVD. The same fate has befallen one of my favorite films of 2018, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Only a few years ago it would be unthinkable for a Coen Brothers film not to find DVD release. Even Roma has had to wait for a Criterion deal to make it to disc. Clearly Netflix, and perhaps other streamers, believe that putting films on disc damages the business plan. So Meirelles doesn’t include DVDs in the lifespan of The Two Popes.

Without DVDs, some cinephiliac consumers are lamenting, rightly, the loss of bonus materials. The Criterion Channel has been exceptionally generous in shifting over its supplements to the streaming platform, but other companies haven’t been. Scholars and teachers rely on the best bonus items, including filmmaker commentaries, to give students behind-the scenes information on the creative process. There are, I understand, rights issues around supplements, and bandwidth is at a premium, but there’s no point in pretending that the loss of disc versions hasn’t been important.

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas put forth the question debated in the directors’ roundtable I mentioned: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

Still, the big changeover hasn’t happened quite yet. Every year has its failed blockbusters, and films big and middling and little (Blumhouse, for instance) still continue. Arthouse theatres, which rely on midrange items, indie production, and foreign fare, are putting up a vigorous fight, emphasizing live events and community engagement.

Meanwhile, streaming makes film festivals and film archives more important. Festivals may host the few plays that a movie gets (as in the 35 fests which ran The Two Popes), and filmmakers, as Kent Jones remarks, are eager for their films to play on the big screen in those venues. Archives will need not only to preserve films but also make classics and current movies available in theatrical circumstances. Smart film clubs like the Chicago Film Society and our Cinematheque keep film-based screenings alive.

Before home video, few film scholars undertook the scrutiny of form and style. Those who did had to use editing machines like these. (One scholar called my study of Dreyer, not admiringly, the first Steenbeck book.) Ironically, just as an avalanche of films became available for academic study, and as tools for studying them closely became available for everyone, most researchers turned away from cinema’s aesthetic history and a film’s specific design in order to interpret their cultural contexts. There were exceptions, like Yuri Tsivian’s efforts to systematically study patterns of shot length, but they were rare.

Whatever the value of cultural critique, one result was to leave aesthetic film analysis largely to cinephiles and fans. Thankfully, the emergence of the visual essay, in the hands of tech-savvy filmmakers like kogonada and Tony Zhao and Taylor Ramos, eventually attracted academic attention. Film analysis has returned in the vehicle of the video essay, which is a stimulating, teaching-friendly format. Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I have participated in this trend through our work with Criterion and occasional video lectures linked to this site.

All this was made possible through the digital revolution, or evolution, and we should be grateful. Still, streaming filters out a lot of what we want to study. It’s clear that, for all their shortcomings, physical media were our best compromise for keeping alive the heritage of critical and historical analysis of cinema. We’ve largely lost physical motion pictures as a contemporary medium. (How many young scholars, or filmmakers for that matter, have handled a 35mm print?) Now, to lose DVDs and Blu-rays is to lose precious opportunities to understand how films work and work on us.

Thanks to all the archivists, collectors, and fellow researchers who made our research so fruitful and enjoyable in the pre-digital age.

A good overview of the streaming business at this point is “The future of entertainment,” in The Economist.

Kristin discusses the fantasy of the Celestial Multiplex with archivists Schawn Belston and Mike Pogorzelski. For examples of how to watch a film on film slowly, go here. Samples of editing-table discoveries are here and especially in the Library of Congress series that starts here. In another entry, I discuss the use of 3D in Dial M for Murder.

P.S. 24 January 2020: Then there’s this, from Facebook.

Dial M for Murder (1954).

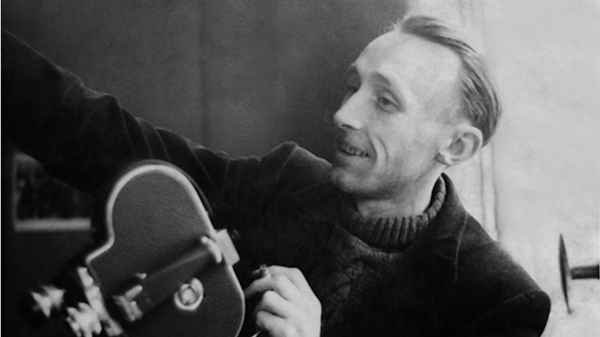

André Bazin, man of the cinema

DB here:

André Bazin was born in 1918 and died on 11 November 1958. In his short life he became, without aiming at it, one of the greatest theorists and critics of cinema.

A central figure in the founding of Cahiers du cinéma, Bazin was also active in building film culture through ciné-clubs and festivals, most notably Cannes and the Festival du film maudit. His writings were poetic, original, and provocative in the gentlest way you can imagine.

As a reviewer he discussed hundreds of releases, and in essay mode he produced subtle reflections on cinema as both medium and art. He wrote about Westerns, pin-ups, Stalinist cinema, documentaries on art and exploration, and of course the commercial storytelling cinemas of France, Italy, and Hollywood. His friendship with two generations of filmmakers–Renoir and Truffaut, among others–gave him a living link to film history. Many would argue that the “young cinemas” of the 1960s, building on both Italian Neorealism and the pictorial styles that crystallized in the 1940s, owe a great deal to the tradition of critical debate he fostered.

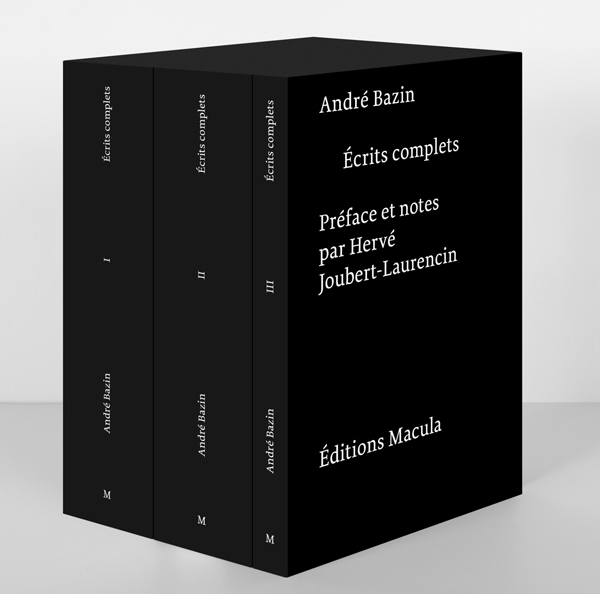

Bazin’s thousands of pieces have now been gathered by Hervé Joubert-Laurencin. A three-volume collection is scheduled to appear this week in a deluxe edition published by Macula of Paris. The press kit, with excerpts, is here.

Beyond reading the work itself, if you want to know more about the man, I think the best place to start is with Dudley Andrew’s biography. It’s a sensitive overview of Bazin’s life and thought, giving particular emphasis to the philosophical and religious influences on him.

Bazin has shaped my thinking about film history and aesthetics since 1967, when I first read Hugh Gray’s translation of What Is Cinema? I taught his work for decades here at Wisconsin, and in On the History of Film Style, I tried to analyze his pivotal role in our understanding of the “development of film language.” That chapter situates his thinking about technique in the context of the “nouvelle critique” of the 1930s and 1940s, a trend that tried to locate an aesthetic suitable for the sound cinema.

Later, I wrote an essay for the German journal montage a/v, which ran a special 2009 issue devoted to Bazin. The original English text, slightly updated, is now available on this site (here, and on the left). That piece suggests how Bazin’s thinking has shaped my own approach to understanding cinema.

Commentators pledged to labels may wonder how a “formalist” like me can find common cause with a “realist” like Bazin. Actually, in both method and substance, his work offers much to the research program I’ve called a poetics of cinema. To see Bazin as being “for” deep-focus and the long take and “against” montage is an oversimplification, it seems to me. He saw more deeply and more widely than that, not least because he was always aware that filmic expression—in style, in narrative—changes across history.

Film criticism owes Bazin an immense debt; he taught us to look closely at what’s onscreen. Elsewhere on this site, we discuss some examples (for example, here and here and here).

There are many ways of thinking about his work, as you can see from the swelling number of articles, books, and conferences devoted to him. He remains a tremendous figure, blending modesty, tolerance, patient attention, close viewing, and bold speculation. Film studies could scarcely exist without him.

The classical Hollywood whatzis

Black Panther.

DB here:

In the academic world, there are conferences and conventions. Conventions tend to be humongous jamborees associated with professional groups like the Modern Language Association and the American Historical Association. They feature panels, workshops, plenary events, book displays, hundreds of papers, and meetings of subgroups–boards, caucuses, and the like. Also sexual liaisons, I’m told. If you want to feel like you belong to a corporation, go to a convention.

Conferences tend to be smaller and focused on single topics. Sometimes speakers are solicited through a call for papers, and sometimes the speakers are invited (the result might be called symposia). I think conferences are more exciting, liaisons aside. Some of the best experiences of my life have been get-togethers like “Imagination and the Adapted Mind: The Prehistory and Future of Poetry, Fiction, and Related Arts” (1999, University of California–Santa Barbara).

Last month, Kat Spring and Philippa Gates of Wilfred Laurier University added another to my list of favorite conferences. “Classical Hollywood Studies in the 21st Century,” which I announced in the run-up to it, was a wonderful gathering of scholars working on American studio cinema from a variety of angles.

Waterloo mon amour

Scott Higgins talks Minnelli.

We heard about production, distribution, marketing and publicity practices, censorship, and fandoms. Mark Glancy analyzed the trade-paper and fan-mag positioning of the Cary Grant/ Randolph Scott household (♥ + ♥?), while Will Scheibel studied discourse around the sad fate of Gene Tierney. Through both close analysis and probing of primary documents, several papers treated racial and gender representation: Charlene Regester on Double Indemnity, Philippa on portrayals of Chinatown, Barry Grant on race in science fiction, Ryan Jay Friedman on African American musical numbers. There was consideration of style and narrative as well, as in Chris Cagle’s case for distinguishing baroque and mannered styles within “1940s Hollywood formalism” and in Stefan Brandt’s tracing of thematic affinities between Finding Dory and The Grapes of Wrath.

I was glad to see the industry and its affiliated institutions get so much attention. Paul Monticone proposed a cultural approach to the MPPDA, while Tom Schatz traced industry developments in the New Hollywood and after. At the level of reception, Peter Decherney traced how digital tools can measure fan engagement with Star Wars. And John Belton, pioneer of detailed technological history, shared a Bazinian take on digital cinema.

Little-appreciated creative workers got to share the spotlight, in Helen Hanson’s paper on Lela Simone (music supervisor for the Freed unit) and Cristina Lane’s study of the career of Joan Harrison, Hitchcock’s “work wife.” Kay Kalinak revealed how composers swiped from themselves, as Tiomkin did in his score for The Big Sky. And there were lots of surprises, as with Shelley Stamp’s revelation of how film noir was sold to female audiences, Adrienne McLean’s account of stars’ running, or at least signing, advice columns, and Kirsten Moana Thompson’s dissection of the unique paint mixtures used in Disney animation.

It wasn’t musty, either. Things were light and friendly, with serious topics treated without pomp. Blair Davis’s obsessive search for science-fiction elements in serials and B films of the 1930s and 1940s, Steven Cohan’s zesty admiration for the “backstudio” picture, Kyle Edwards taking Torchy Blaine (and her budgets) straight, Dan Goldmark’s affectionate dissection of Pixar’s use of memory, and Liz Clarke’s enthusiasm for heroines of World War I films–all showed that classical filmmaking can be studied with both admiration and rigor. Not to mention Richard Maltby’s patented wry wit. (“David, you know I’ve always been a vulgar Marxist.”)

I have to signal my pride in witnessing how many of the participants were affiliated with our program. Tino Balio on MGM, Scott Higgins on Minnelli’s staging, Lisa Dombrowski on late Altman, Charlie Keil (with Denise McKenna) on Hollywood as a “social cluster,” Eric Hoyt (doyen of Lantern) on trade papers, Mary Huelsbeck on archival resources, Vince Bohlinger on US censorship of Soviet films, Maria Belodubrovskaya on Stalinist movie plots, Brad Schauer on Universal’s acting school, Kat Spring on how the trade papers conceived the musical, Patrick Keating on using the video-essay form to analyze lighting–all showed how you can pack a lot of ideas and information into 18 minutes. I was elated to see the learning and energy these several generations of Wisconsinites displayed.

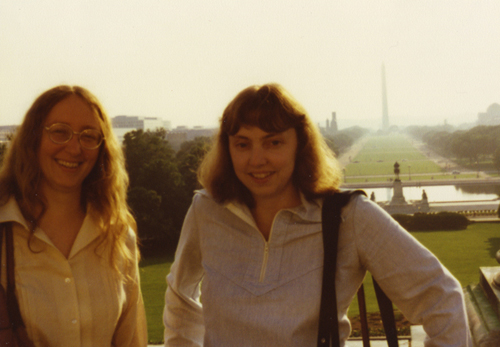

The authors of The Classical Hollywood Cinema got in their licks. Janet Staiger talked about current screenwriting practices, highlighting the role of gatekeepers (agents, script analysts) and the need for vivid writing that can indulge in flourishes–“movies on the page.” Kristin drew on her Frodo Franchise project to show the problems, but also the advantages, of researching an event while it’s happening.

As for me, I got to give the keynote lecture. It was an intimidating situation, but it did allow me to make the case for analyzing films in relation to norms. Since the conference, I’ve thought more about the idea of Hollywood “classicism” and how we might analyze changes in it.

Not exactly classical, but sweet

Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson, on a research trip to Washington DC 1979.

Now, some thirty-three years since we wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, we all know a lot more. There’s scarcely a paragraph of my chapters I wouldn’t change, and much of the research I and others have done since would correct, nuance, and deepen their claims. (I think Janet’s and Kristin’s contributions survive better than mine.)

What did we three do? I’d say we sought to provide a comprehensive description and explanation of narrative and cinematic techniques in the studio years. We traced ties between craft conditions and production decisions on the one hand and the resulting film on the other. We argued that studio division of labor allowed not only reliable production but a standard menu of artistic options. Going beyond the individual filmmaker, we traced how adjacent institutions–not just the studio but professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the like–worked to define and maintain the style. We also suggested reading the professional literature rhetorically, seeing industry discourse as a way for individuals and organizations to set agendas and crystallize preferred solutions to problems. We tried to show how technological innovations like color and widescreen cinema took particular turns because of this matrix of activities. And we began the project of treating Hollywood filmmaking as a flexible but bounded set of norms of style and story.

What did we three do? I’d say we sought to provide a comprehensive description and explanation of narrative and cinematic techniques in the studio years. We traced ties between craft conditions and production decisions on the one hand and the resulting film on the other. We argued that studio division of labor allowed not only reliable production but a standard menu of artistic options. Going beyond the individual filmmaker, we traced how adjacent institutions–not just the studio but professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the like–worked to define and maintain the style. We also suggested reading the professional literature rhetorically, seeing industry discourse as a way for individuals and organizations to set agendas and crystallize preferred solutions to problems. We tried to show how technological innovations like color and widescreen cinema took particular turns because of this matrix of activities. And we began the project of treating Hollywood filmmaking as a flexible but bounded set of norms of style and story.

The book received both praise and criticism. With the passage of time some issues have become clearer, and some critiques have, as far as I can tell, lost some force. For instance:

The term. Why call it “classical”? Humanists love to debate terminology. But we pointed out in the book that we inherited the term from French commentators, as far back as the 1920s, and from more recent academic circles. Nothing hangs on the name, actually. We could call it “standard” style or “mainstream” style or X style, and the descriptive claims we make about it will hold good. As I indicate in the book, the “classical” label suggests an effort toward coherent, unified storytelling–at least in comparison with the more episodic narratives we find in other traditions. (In Planet Hong Kong I reflect on more episodic approaches.)

The focus on production. Why not talk about distribution, exhibition, or reception? (A) It would require a much bigger book. (B) Production and its affiliated institutions are the most pertinent and proximate causal factors in shaping the films as we have them. (C) It’s not clear that conditions further along the chain have many consequences for the way the movies behave. (D) You can’t talk about everything. (E) All of the above.

The term, again. By calling Hollywood storytelling and style “classical,” don’t you ignore its ties to modern culture? This view, advanced most fully by Miriam Hansen, suggests that the causal factors we trace aren’t broad enough; we don’t consider the rise of urban culture and its associated patterns of behavior and experience. The modern city purportedly alters people’s perception and rhythms of life, and these shape the way films are made. Hollywood’s aesthetic is better conceived as “vernacular modernism.” I’ve responded to this line of argument in On the History of Film Style, where I argue that the position has an equivocal conception of urban experience and how perception works. Moreover, these critics haven’t shown how the cultural forces they invoke have shaped the narrative strategies and fine-grained stylistic features we analyze. The urban experience would have to have a sort of feedback effect on the filmmakers (given the proximity of production, as above). What’s the causal story to be told here? There’s also a problem of delayed timing: the modern city, choked with traffic and distracting displays, antedates the 1910s, when the Hollywood style crystallizes. On the whole, the modernity position seems to me to rely on analogies, not causation.

A rage for disorder. How unified are these films, really? Critics sometimes point to musicals, action movies, noirs, comedies, and other films that seem narratively disjointed. We argued that classical construction was a goal, not always achieved, but even genres that seemed to favor loose plotting put their films together fairly tightly. In addition, principles of both surface structure (dialogue hooks, continuity cutting) and plot structure (goal orientation, deadlines, appointments, etc.) bind the action in most feature-length pictures. In more recent years, analyses by Kristin in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and by me in The Way Hollywood Tells It and Reinventing Hollywood, along with some entries on this site, have, I think, convinced people just how carefully sculpted a classical film can be. Fights, chases, and escapes aren’t mere spectacle; they advance the story by creating new obstacles or revealing betrayals or killing off the hero’s best friend. I have, though, come to accept coincidence as being more important than screenwriting gurus have claimed. Yet even here, coincidence is absorbed into a pattern of cause-and-effect and motivation that isn’t willy-nilly. In short: Where you find planting and foreshadowing, you’ll find “classical” unity.

The neglect of auteurs. Why treat the output of hacks and mediocrities as on the same level as the work of the great filmmakers? Andrew Sarris promoted the idea of writing American film history as the accretion of the “personal visions” of directors. And historians of other arts routinely conceived of history as a succession of exemplary works produced by exceptional creators. But we were asking different questions. We sought to understand a tradition as a whole, and to explain its emergence and longevity. That’s an effort of value in its own right. Moreover, an auteurist could benefit from knowing relevant norms, because then one could pinpoint the distinctiveness of individual filmmakers. Throughout his work, Sarris occasionally signaled when a director made an uncommon choice of camera setup or cutting, and this gesture presupposes a norm in the background.

The schlock of the new. By stopping your survey in 1960, don’t you assume that a post-classical cinema came next–one less concerned with goal-directed plots and “invisible” style? We argued that the industrial conditions for the studios faltered around 1960, but the creative and labor practices (division of labor, hierarchy of control, etc.) continued into the present. We thought that classically constructed films dominated output afterward (Jaws, The Godfather, The Exorcist). Not that there aren’t changes. We suggested that many of the changes detectable in the more unusual “New Hollywood” films of the 197os are traceable to the influence of European art cinema; those principles of construction were blended with genres and stylistic patterns characteristic of the studio tradition. (Since then, other researchers have found this to be the case.) In addition, there are many post-1960 films which are “hyperclassical.” Back to the Future, Jerry Maguire, Die Hard, Hannah and Her Sisters, and others are “more classical than they have to be,” with intricate patterns of motifs and plotting–packed, we might say, with classical features. The same goes for many films we’ve discussed in our blog entries since 2006.

The monolith (no, not 2001). So the classical style never changes, is always in force, can’t go away? Ridiculously monolithic! Actually, we argued that classical filmmaking does change, but within boundaries. I invoked Leonard Meyer’s notion of “trended change,” in which

change takes place within a limiting set of preconditions, but the potential inherent in the established relationships may be realized in a number of different ways and the order of the realization may be variable. Change is successive and gradual, but not necessarily sequential; and its rate and extent are variable, depending more upon external circumstances than upon internal preconditions.

This seems to me to capture change in the studio tradition. Hollywood films can have 400 or 2000 shots, they can be told chronologically or not, they can have single protagonists or multiple protagonists, and there will be a lot of variety at any moment. But they will still tend to obey canons of classical staging, camerawork, cutting, sound work, and dramaturgy. And those changes are, as Meyer suggests, not generated from within the style, as a necessary unfolding like the growth of an organism. The variations are created by external circumstances such as budget constraints, production trends, influential models, new tools, fashion, competition among filmmakers, and the like. I’d make the analogy to the well-made play, which has survived as a model of plotting for nearly two centuries, but has allowed for a huge variety of manifestations, from Ibsen to Doubt and beyond. Perhaps perspective painting and Western tonal music, both robust traditions, would also exhibit trended change within history.

In the book, I tried to analyze levels of change by a three-tier model that still seems valid, though perhaps too abstract. Coming back from Waterloo, I began to see a way to specify a little more the kinds of change we can track, at least in terms of narrative construction. Maybe this effort will also help us understand why we think the “classical” system changes more than it does.

Black Panther in three dimensions

Narrative theorists often distinguish between “story” and “discourse.” There’s the causal-chronological string of events, and there’s the way they’re presented in the text we have. There are other terms for the distinction (story/plot, fabula/syuzhet), and they aren’t completely congruent. In an essay reprinted here I propose that we can better think of narratives as having three dimensions: the story world, the structure of the plot, and the narration.

Start with narration. Why? Because it’s the flow of information we encounter moment by moment, given to us through all the resources of the medium. Black Panther begins with a visual representation of how vibranium created the nation of Wakanda, while we hear on the soundtrack a father recounting the tale to his son. (Here the film’s narration is given as both pictorial and voice-over.)

In an earlier version of this entry, I said that it was T’Chaka speaking to T’Challa. But Fiona Pleasance wrote to point out that the voice is actually that of T’Chaka’s brother N’Jobu telling his son N’Jadaka, who will grow up to be Killmonger. They’re living in exile, which motivates the need to rehearse the nation’s origins.

The narration isn’t only giving exposition about Wakanda’s history. It’s establishing a hierarchy of knowledge, in which the father is presented as knowing more than his son. This is important for a later revelation of what aspects of the past are suppressed. And flashbacks and other narrational choices will further channel the flow of information. Soon after the prologue, we jump back to 1992, when T’Chaka learned of N’Jobu’s affiliation with arms dealer Klaue.

With or without voice-over, the regulated flow of story information will continue throughout the movie. Out of this narration we build a story world. We’re cued to construct characters, to register their roles and attitudes and feelings, to sense their hopes and fears. We also construct the story’s physical world, with its geography and furnishings and rules. Very quickly, for instance, we understand that Wakanda is a land of utopian technology but ruled by ancient tribal lore and rites. Through redundant information we learn of T’Challa’s family and friends, past conflicts among characters, and the threats to Wakanda.

Okay, so we have narration that coaxes us into co-creating a story world. What’s left for my third dimension, plot structure? Kristin convinced me that it’s another level of construction, one that organizes the story world into a comprehensible pattern that can in turn be transmitted via narration. She argues that classical films often have four large-scale parts (not three acts), each typically running about half an hour. Those parts focus the action in the story world around the characters’ goals.

In the Setup, running about half an hour, we meet the main characters and learn their goals. In the Complicating Action, another half hour more or less, the goals get redefined as a result of new obstacles. Then comes the Development, which is largely a holding pattern. Here we get backstory, character portrayal, fantasies and flashbacks, the upgrading of secondary characters, and elaboration of motifs. At the end of the Development, a crisis develops; at this point we know nearly everything we need to know and can concentrate on the outcome. Now comes the Climax, usually with a deadline pressing on the action. At the end, with the action largely resolved, there’s an epilogue (or “tag”) that celebrates the final state of things.

This anatomy of plot structure echoes the classic screenplay manuals up to a point. The Setup corresponds to Act I, the Climax to Act III. The Complicating Action and the Development in effect split the second act. But Kristin’s layout is more precise, I think, because she shows that goals and obstacles change between the first and second part. She also points up the more or less arbitrary delays and detours that prolong the action in her third part, the Development. This “desert of the Second Act,” as screenwriters call it, can now be seen as doing its own distinctive narrative work, not least prolonging suspense.

This structure didn’t have to have such sharply defined segments. Why can’t the setup be an hour, dawdling over introducing the protagonist’s goals? Why not cut out the Development, if it’s mostly delay? The Hollywood tradition has created this distinctive, tight form as one solution to the problem of organizing an appealing narrative at feature length.

Take Black Panther again. The Setup charges T’Challa, newly made king, with responding to Klaue’s theft of a precious Wakandian tool made of vibranium. (Screenplay gurus sometimes call this the “inciting incident.”) At the 35-minute mark T’Challa, Okole, and Nakia set out on a mission to retrieve the artifact. At sixty-one minutes, the midpoint, the goals need revising. Klaue is dead, the Wakandans’ ally Ross is severely wounded, and the real antagonist is revealed: the fierce fighter Erik, aka Killmonger.

The Development provides important backstory involving T’Challa’s uncle’s child N’Jadaka (more flashbacks, including replays of the 1992 scene presented in the Setup–revealing the child Erik as on the scene). T’Challa’s allies flee from Killmonger, who prepares to use the precious vibranium to make weapons for world insurrection. T’Challa, near death, has been rescued by his rival the Jabari chieftain Baku. All pretty typical Development, moving the hero toward his “darkest moment” and facing him with a deadline.

The Climax, which tends to be the shortest section in most films, starts at about 99:00. It’s a gigantic battle scene, involving air combat, ground fighting, and the confrontation of T’Challa and Killmonger–all crosscut for maximum suspense. After the resolution, we get a tag showing a montage of life returning to normal, T’Challa kissing Nakia, and another visit to the 1992 world when T’Challa comes calling in a space ship.

The film has the characteristic double plotline, a romance line of action (will T’Challa and Nakia reunite?) and one centering on a project (keeping vibranium out of the wrong hands). Major developments are carefully foreshadowed. The paternal voice-over establishes the Jabari tribe’s isolation, and Baku’s crucial role is planted when he challenges T’Challa to mortal combat. Later Baku will save the young king. Kristin also points out the importance of motifs in tightening classical structure. Here we get recurring lines (“”I never freeze”/ “Did he freeze?”), the lip that identifies a Wakandan, the importance of border patrols, and the ring that reveals Erik as kin to T’Challa. Parallel scenes–two waterfall fights, two burial ceremonies with attendant ephiphanies, two street strolls of T’Challa and Nakia–measure significant dramatic differences.

Despite being an installment in a much bigger saga, Black Panther is a solid example of classical construction. (I don’t have to explain how it obeys the rules of continuity staging and editing, do I?) A hundred years after the Hollywood storytelling system settled in, it’s still shaping the movies coming out each Friday.

Main attraction: Worldmaking

Why have so many smart people thought that studio storytelling changed drastically after 1960, or 1945, or 1977? I think it was because trended change was happening along two of these three dimensions.

Narrationally, there were trends toward innovation. I argue in Reinventing Hollywood that 1940s filmmakers consolidated narrative devices that had appeared piecemeal in the silent and early sound eras. Those strategies–flashbacks, voice-overs, subjective sequences, self-conscious artifice, mystery plotting–gained a new prominence and were explored with unprecedented ingenuity. The 1990s was another period of experimentation, reworking all those techniques and more, such as network narratives and forking-path plotting. These suggested to sensitive critics that something new was up. For me, they show the versatility of the classical system, its ability to explore what Meyer calls its “preconditions.”

One broad narrational change I’d now emphasize is the tendency to be more elliptical. The opening of Black Panther doesn’t show us N’Jobu speaking to his son. This misled me, and perhaps some others. Executive producer Nate Moore explained:

“We landed on N’Jobu telling the story to his son, which wasn’t our first choice, but ultimately felt really satisfying,” said Moore. “Hopefully on repeat viewings you go, ‘Oh that’s who I was listening to, OK that’s cool.'”

A film in earlier periods would have shown us the speaker and listener, but we’ve so “overlearned” the convention of a tale told by an elder to a child that we need only one set of cues, on the soundtrack. Still, the uncertainty about the speakers–we haven’t met any of the characters yet–offers less redundancy than is traditional. I’m reminded of the old man’s voice-over that opens The Road Warrior; only at the very end do we learn his identity.

The elliptical prologue exemplifies what’s perhaps the most common change in narrational strategies across history. A lot of new practices, such as the substitution of straight cuts for dissolves and fades between scenes, involve this sort of reduction in redundancy. It’s possible because Hollywood films are traditionally quite repetitious in doling out story information, as is indicated by the infamous Rule of Three. (Once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once for Slow Joe in the Back Row.) Still, as is typical of trended change, not every film must adopt an elliptical technique. Black Panther‘s beginning could easily have shown us father and son talking, without any sense of being old-fashioned.

The suppression of the prologue’s speakers not only puts the emphasis on the tale but adds a bonus for repeat viewings. This is the sort of “thickening” of classical style I analyzed in The Way Hollywood Tells It. I proposed there that making the films available on video formats enabled fans to hunt for fine points and Easter Eggs. Nate Moore’s comments seem to presuppose this sort of fan-driven recidivism. Such sneaky bits for insiders weren’t unknown in earlier periods (I talk about some here and here and here), but the ability to scan and pause DVDs made such games more common.

The bigger changes across Hollywood history, and the ones that constantly impress observers, spring from the movies’ story worlds. The popularity of fantasy and science fiction is, from this standpoint, an extreme instance of the most common way that the tradition refreshes itself. Most of the novelty of Hollywood, I think now, involves worldmaking, big or small. Find new milieus, new characters, new situations. Create conflicted protagonists–fallible, vulnerable, torn by indecision. Turn the heterosexual romance into a gay one. Build your plot around an ensemble (Grand Hotel, Nashville). Take the heist formula and feminize it (Ocean’s 8). And on and on.

Repopulating the story world has another advantage: it yields a new range of thematic implications and thus invites interpretation. Get Out, a film we discussed a bit at the conference, calls on both specific horror-film conventions (the mad scientist, the innocent victim lured to a corrupt community) and broader classical conventions (a double plotline, a restricted viewpoint for suspense and surprise, 1940s dream states, a last-minute rescue). What made the film intriguing and controversial was turning the white bourgeoisie into modern plantation seigneurs re-enslaving African Americans. This refashioning introduces thematic material that can provoke public discussion.

You can call this endless remaking of story worlds unimaginative. But the variorum impulse, this combinatorial cascade of materials and techniques, seems typical of popular art. Art makers take familiar schemas and rework them in novel ways. I’m not exactly saying that everything is a remix, but everything does start from a point of departure in some tradition. Even Cubist painters needed the work of Cézanne and the genre of the still life in order to contrive their innovations.

Moreover, we’re far more sensitive to the story world than the other dimensions of narrative. We’re interested in other persons (or person-like agents, such as Dory), so naturally we’re quick to register the new people, places, and things that a movie prompts us to co-create. Narration and plot structure, although they have immense impact on us, are far less visible. So it’s not surprising that the most imaginatively gripping novelty in mainstream narrative film involves the creation of fresh agents and arenas for story action.

Compared with the story worlds, Kristin’s four-part-plus-epilogue template is far less noticeable. Yet it is a stable and enduring dimension of Hollywood storytelling. Given characters with goals, the narrative structure squeezes those into a sturdy and quietly familiar mold of rising action, delayed action, and culminating action. The strictness of the form, with its well-timed turning points and echoing motifs, seems as reliable as the conventions of narration. It’s a stubborn, persistent feature that testifies to the continuing power of the classical model of narrative.

I can’t claim to have fathomed all the principles of classical storytelling and style. Still, I think we’ve made progress in understanding the engineering, so to speak, of one major cinematic tradition. And it doesn’t exist in splendid isolation. Hollywood’s continuity editing system provided a lingua franca of popular cinema worldwide, and Hollywood narrative structure and narration has been borrowed, wholesale or piecemeal, in other national traditions. Filmmakers, having found a bundle of principles that are understandable and pleasurable to wide audiences, have clung to them for a very long time. Call it classicism or whatever, it’s real and strong and it works pretty well and I bet it’s not going away any time soon.

Thanks to Kat and Philippa for inviting us to their splendid conference. I believe that a book will collect the papers given there; when that happens, we’ll alert you.

More thoughts on our book can be found at “The Classical Hollywood Cinema twenty-five years along.”

The ideas in this entry stem from the books mentioned above, from Poetics of Cinema, and from several other items on our site. If you’re curious, you can look at Kristin’s explanation of the four-part structure and two pieces where I develop her template in relation to the action movie and in relation to traditional act structure. For application to some recent films, see this entry from 2016 , this one from 2017, and this one from last January. An analysis of The Wolf of Wall Street illustrates the three dimensions of film narrative.

P.S. 15 June: Fiona Pleasance, who corrected my attribution of the prologue’s voice-over, helpfully adds:

It could therefore be argued that not seeing the speakers is a weakness of the film, leading as it does to such confusion.

Personally I believe that, narratively, it does make more sense for the speaker to be N’Jobu. Growing up in Wakanda, as T’Challa does, we can assume he would learn about his country’s past by osmosis, without the need for his father to reiterate it. Such stories become much more important for exiles like N’Jobu and his son.

I believe this does not negate the idea of the father knowing more than the son, which is also addressed in Killmonger’s vision after taking the heart-shaped herb, when he confronts the image of his father, just as T’Challa has done. Also, Killmonger at one point refers to hearing his father tell “fairy stories” about Wakanda, which he came to believe were just that. (Or words to that effect. I’m working entirely from memory; I can’t check as the DVD hasn’t been released in Germany yet!).

Thanks to Fiona for writing! If other readers have further thoughts, they should correspond.

Some of the Badger brigade: Brad Schauer, Vince Bohlinger, Masha Belodubrovskaya, Lisa Dombrowski, Patrick Keating, and Lisa Jasinski.