Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

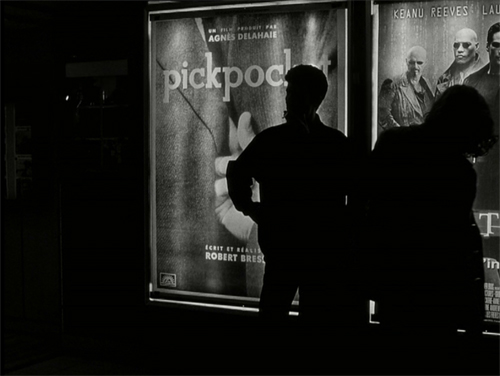

Godard: The power of imperfection

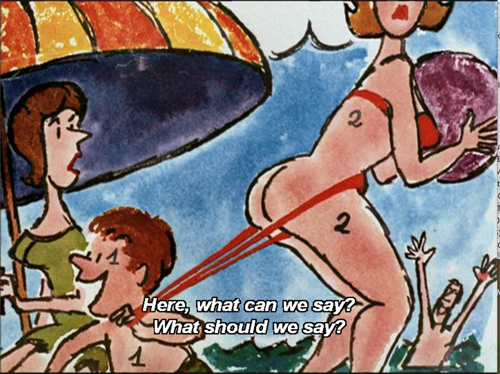

Opening credits of Bande à part (1963).

DB here:

He was a sketchy fellow, to put it mildly. Childhood episodes of theft were followed by larceny as an adult, when he stole his grandfather’s Renoir and swiped cash from the Cahiers du cinéma till. Notorious for taking funding for projects that were never made, he once contracted for $500,000 to create a film on the Museum of Modern Art. He declined to visit the museum and instead shot the footage from stills at home. When The Old Place was finished, he agreed to introduce it in Manhattan. Hours before he was about to fly out (on the Concorde) he canceled, using anti-American cinephilia as his excuse: “I will return to New York when the films of Kiarostami are playing on Broadway.”

He liked to fight. Friends, romantic partners, performers, producers, government officials, and critics all felt his wrath. Jane Fonda was the target of Letter to Jane, a critique of a photograph of her meeting the North Vietnamese. The voice-over narration insisted it was not an attack on her as a person but as a “star.” Breaking with Truffaut led Godard not only to harangue his former pal (“liar”) and the films he made, but demand money so that he could make a film in response to Day for Night. Truffaut’s twenty-page reply called him “a piece of shit on a pedestal.” They never spoke again, and Godard’s remarks after Truffaut’s death praised him as a critic but omitted mention of his films.

Meeting Professor Pluggy

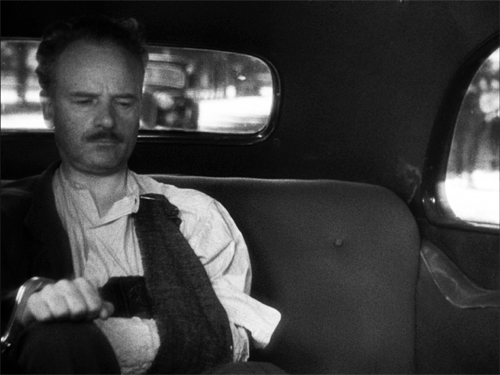

King Lear (1987).

I never had an abrasive encounter with Godard, but I always sensed that he was aloof at best. My first, very brief meeting was in spring of 1973 when he and Jean-Pierre Gorin visited the University of Iowa with Tout va bien (1972). Onstage, he was calm and earnest, while saying fairly provocative things. (Go here for a record of one session.) Asked what he thought of The Godfather, he replied: “The Godfather is shit. But there is a part of me that loves shit.” My eyewitness encounter took place in an elevator, when the host told Godard and Gorin that their schedule now had an empty hour. Godard said: “I am a prostitute. Why do you not use me?”

I had more prolonged exposure to him in 1981, when he visited a lecture series I was giving at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. He was touring with Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980), and the series director Melinda Ward took the opportunity for us to do a career review onstage. I planned to juxtapose clips from his work with those by other directors, and called him at Rolle to review my choices. He listened politely and said they would be fine, adding: “No matter what you choose, it always works.”

The session turned out well, with Godard modest about his efforts compared to those of Preminger (“like Manet”) and others. The only time the audience seemed ruffled was when he said of Jerry Lewis and the clip from The Ladies’ Man: “He is Robert Rauschenberg” (seems reasonable). For a couple of days Kristin and I drove him to interviews around town, and he spent his time reading Variety, noting only that he was pleased that Gance’s Napoleon was doing good business. Attempts to engage him in conversation were fruitless. But once onstage he was alert and genial, all soft speaking and gentle smiles.

The big stir came the following night with the screening of Sauve qui peut. A considerable portion of the audience objected to the film’s sexual politics. The most fraught moment, as I recall it, went like this:

Woman in the audience: Why do you make films only about women prostitutes, not male ones?

JLG (after a pause): They are different things.

Woman: How can you claim to talk about a women prostitute’s life?

JLG: Well, every time I hire a prostitute I ask her about her experiences.

Audience: stunned silence.

My last encounter was the most embarrassing. Invited to a conference on his work at Liège in 1986, I had horrible jet lag. In the first evening, a Q & A with the master, I made the mistake of sitting, as usual, in the front row. The problem was I kept dropping off to sleep. Every time I blinked awake, Godard was staring impassively at me. I thought no one noticed, but afterward one of the conference speakers said: “He was looking at you sleeping all the time.” Jesus.

I consider myself lucky to have escaped the treatment others have reported. Maybe it made it easier for me to admire his work. Yet even that admiration is tempered by exasperation. Bypassing von Stroheim and Buñuel, he might be the most annoying great filmmaker of all.

I’m not referring just to his obsession with female nudity, or his pretentious wordplay, or his pseudo-profundity. His provocation goes all the way down to the very texture of the film. In form and style he embraced irregularity. He will create a scene that’s conventionally beautiful, only to spoil it with a harsh disjunction or a silly gag or a deflating commentary. He seems to want to coax us to enjoy imperfection. His deformations of story and style are the result of testing the limits of what cinema had done, and might do.

Early work: Puncturing the plot

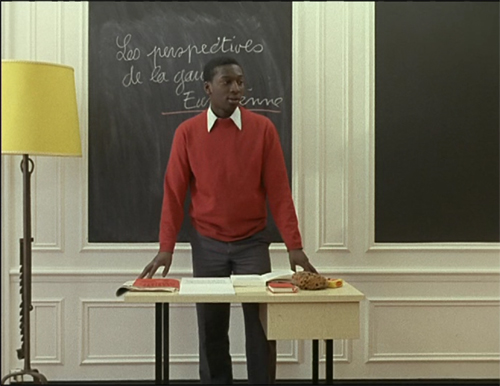

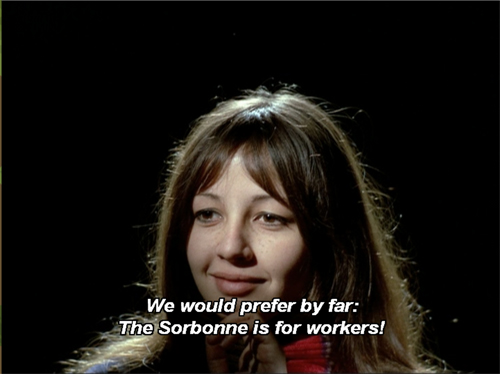

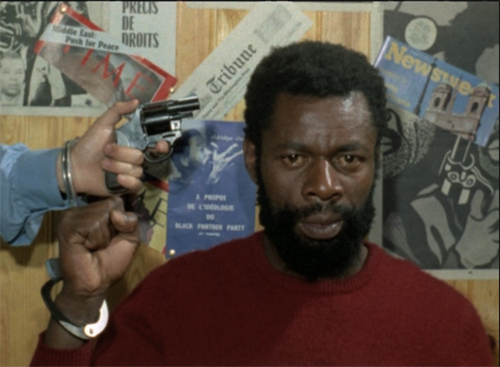

La Chinoise (1967).

Everything about him is troublesome. As a rough approximation, we tend to divide Godard’s career into three parts, but the results are peculiar. The early New Wave period runs from 1959 to 1967. The second, his overtly “agitprop” phase runs until 1980. Then we have “late Godard,” which dates from Sauve qui peut (la vie) until his death this year. What other artist has a “late” period running over forty years?

In all these periods, it’s common to say that Godard attacked, even destroyed, previous forms of cinema. But it helps to specify a bit more. I want to focus on his peculiar relation to narrative.

He often derided Hollywood’s reliance on stories, but throughout his career he depended on them. Asked about Hail Mary, he replied that the Bible had many good stories one could use. The project he proposed to Coppola about Bugsy Siegel and the founding of Las Vegas was initially titled simply “The Story.” Even the collage form he utilized in his last completed film, The Image Book, ends with a fictional tale about how Sheikh Ben Kadem, ruler of a kingdom called Dofa, tried to resist American imperialism.

One reason his early work succeeded, and survives as a body of classics, is that he relied on narrative conventions of traditional filmmaking. He rummaged through familiar genres: the couple on the run (Breathless, Pierrot le fou), spy intrigue (Le petit soldat), musical comedy (Une femme est une femme), social drama (Vivre sa vie, Two or Things I Know about Her), war picture (Les carabiniers), marital drama (Contempt, Une femme mariée), a robbery scheme (Band of Outsiders), a detective investigation (Alphaville, Made in U.S.A), and young romance (Masculin féminin).

More radically than his New Wave colleagues, Godard transforms these conventions. Sometimes he de-dramatizes intense situations, as in the violence of Le petit soldat and Les carabiniers. More commonly, he punctures the stories with digressions, skits, and uncertainties about character psychology. There’s also often a mockery of the very conventions invoked. Nonetheless the genres provide an armature for the audience to cling to, and the plots wrap up with more or less decisive endings.

With La Chinoise, not only does the plot swerve from traditional genres (I suppose it’s a perverse roommate-relationships story) but the dynamic of the drama becomes overtly rhetorical, with both the characters and the overall narration setting out political theses. Weekend has a narrative core–a couple set out to visit and kill a rich relative–but the familiar journey schema becomes apocalyptic as the bourgeois encounter a world bent on revenge for oppression.

One strategy Godard pursues is to deform narrative by mixing in other formal principles. The later early films introduce passages cast in rhetorical form, as when characters indulge in extensive arguments about philosophy or politics (La Chinoise, Vivre sa vie).

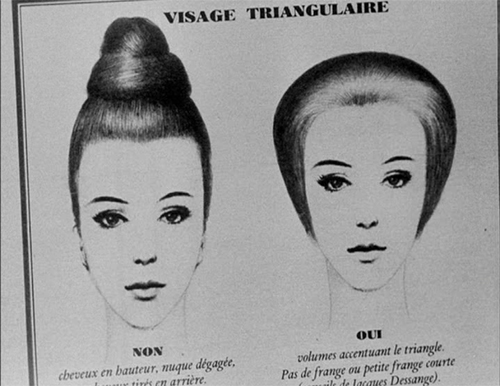

The early work also introduces passages of associational form. More and more often, Godard interrupts the action with cutaways to images that create commentary, analogies, and contrasts. Book titles are the simplest examples, but we also get the shots of fashion advertising interpolated into Une femme mariée and the landscape of consumer goods inserted into Two or Three Things.

With Le gai savoir of 1968, narrative is sidelined altogether as the primary characters conduct a political deciphering of a cascade of mass-media images.

The late 1960s-early 1970s quasi-Maoist films that Godard made with Jean-Pierre Gorin, sometimes under the rubric of the Dziga Vertov group, rely mostly on rhetorical and associational form, as in One Plus One and Pravda. Vladimir and Rosa, however, returns to narrative in providing a caricatural replay of the trial of the Chicago Eight, and Tout va bien is like the early work in embedding its political commentary in a more or less linear plot line.

After the break with Gorin, Godard continued to mix narrative and other formal options in Numéro deux, Ici et ailleurs, and several striking documentaries of the mid-1970s. Seen today, Comment ça va looks ahead to both the style and the construction of his late films in tracing two couples caught up in the politics of the mass media.

Style as rewriting

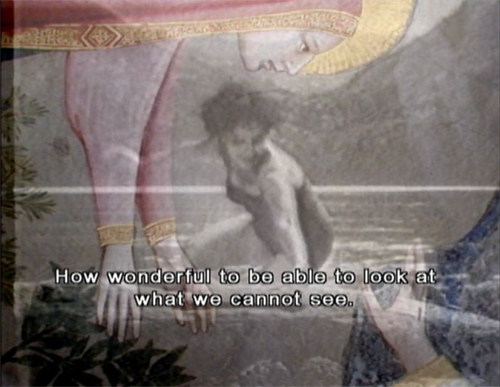

JLG par JLG (1995).

By emphasizing Godard’s reliance on narrative principles I don’t mean to reduce his originality. Like a Cubist painter creating a portrait or a still life, he needs some norms in order to introduce his disturbing deformations. He gives with one hand and takes away with the other, and to feel his work’s disruptive force we need a tacit background of what’s ordinarily done.

The same holds for matters of style. Most scenes in the early films rely on standard continuity, as I tried to show in one chapter of Narration in the Fiction Film. Even a film as fragmentary as Vladimir and Rosa depends on eyeline-match cutting.

Godard’s limited obedience to standard style makes the deviations stand out. In the shots above, the curtain background forestalls expectations of real space. Often the calculated disruptions of continuity have an arbitrary air, as if there’s no particular motivation except the opportunity to try something new. The celebrated jump cuts in Breathless, for example, seem to have no specific functions as motifs or narrative cues. They register as glitches, gratuitously spoiling a shot. Like DJ scratches and skips in hip hop, they come to form percussive passages that can be appreciated for themselves.

The early films try everything: labyrinthine camera movements, shots too short to be grasped, abrupt dropouts of sound and image, wisps of voice-over. Drama could be punctured or entirely suppressed. Alphaville expands a moment of suspense into a lyrical interlude, while Un petit soldat, after arousing our concern for the woman the hero meets, shoves her torture and death offscreen, reported in a tossed-off line of dialogue. All of cinema was simultaneously available to the New Wave directors, who at Langlois’ Cinémathèque saw a Griffith film alongside a Nicholas Ray picture. Godard gleefully ransacked film history, while deforming each device to see what he could make of it.

For example, Godard gave new life to a compositional option I’ve called planimetric framing. The camera shoots figures perpendicular to the background and places those figures frontally or in profile. Earlier it had been an almost ephemeral moment. Godard makes it a stylizing gesture, offering pictorial abstraction that short-circuits naturalistic drama (Pierrot le fou, Two or Three Things I Know about Her, Vladimir and Rosa).

What binds these all stylistic tactics together, I think is a broader narrational strategy. Godard carries the auteur theory to a new limit. In watching the film, we become aware not just of “a narrator” but of a specific agent, Godard the director, who insists that his story world is created and transformed by the practices of cinema. This isn’t just “Brechtian” distancing but persistent signs of this particular filmmaker’s creative work. Godard invites us to admire his sometimes annoying audacity.

The intertitles are the most evident signs of this agent’s activity, but so too are the unrealistic staging, the abstract compositions, the geometric camera movements, and especially the manipulations created in post-production. Sound mixing cuts off noises, muffles dialogue, provides anonymous voice-overs, scatters audio across many channels, and wedges in chunks of music. Post-production is seen as offering the filmmaker’s final, if sometimes inconclusive, revisions of his creation. It’s as if a novel were published as the copy-edited and marked up proofs of the author’s manuscript.

Critics are fond of saying that 1960s Godard changed the language of cinema. That’s sort of true, but we should remember things that were abrasive or alluring in his films have mostly been tamed by their assimilation to mainstream uses. Chapter breaks and intertitles are now recruited to create coherent story connections, as in Tarantino. The handheld camera is commonplace, but it serves chiefly as a wavering substitute for standard framing. His planimetric framings create a painterly abstraction, but in the hands of Wes Anderson they function as seriocomic establishing shots. Today’s directors use jump cuts mostly to compress time between stages of an action, not to annoyingly break the flow. And even our filmmakers who treat auteurism as a brand do not create the sense of the filmmaker’s hand fooling with every image and sound on the fly. Godard’s unpredictable tweaking asks us to adjust to a film that will undercut its own effects.

It makes me revert to a quotation I’ve used before. Supposedly Picasso told Gertrude Stein: “You do something new and then someone comes along and makes it pretty.” It’s worth noting that as mainstream films adopted his early technical tics, Godard abandoned most of them. His later work locks down the camera, favors depth staging over planimetric flatness, and avoids jump cuts. Three separate, disjunctive shots in Hélas pour moi show how he can reinvent continuity jumps, this time to harshly italicize a gesture: departure.

Late films: What the hell is going on?

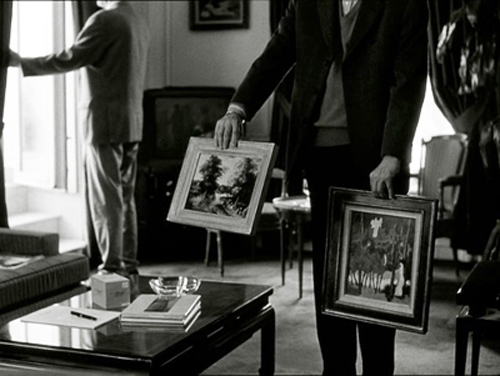

Film Socialisme (2010).

The late films of Godard are tremendously varied, and I can’t claim to have seen, let alone assimilated, all the shorts and medium-length projects. But consider just two main types of features. There are the “film essays,” the prototype being Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998). His last feature, The Image Book, is also an instance.

I’m disinclined to call them essays, since the ones I know don’t coherently marshal evidence to support a line of argument. They’re largely associational collages of found footage, suggesting pictorial or conceptual links among them. If you want a literary analogy, the poetry of Whitman or Pound would be close. The collage films also have rhetorical overtones, presenting ideas about, for instance, the way Hollywood evolved after World War II in Histoire(s). In its mixture of rhetorical and associational patterning, Le gai savoir was a rough prototype for the collage films; they simply delete the characters whose dialogue frames a flurry of images and substitute Godard’s own voice, or a merger of other voices.

I’m in that minority of Godardolators who find the collage films of limited interest. I find the philosophizing often facile, the claims about film history too broad, the politics obscure and even naive. Most essays take opposing views seriously enough to confront them, but Godard doesn’t rebut positions. He contents himself with post-production reworking of the imagery, twiddling the knobs to destabilize the image. As in the early films, his documentary images can’t escape transformation by the all-powerful filmmaker. At the least, comments might be scrawled on the images. But there will also be superimpositions, spasmodic slow motion, and freeze frames. Color values are garishly recast and aspect ratios pinched or stretched (Histoire(s), The Image Book).

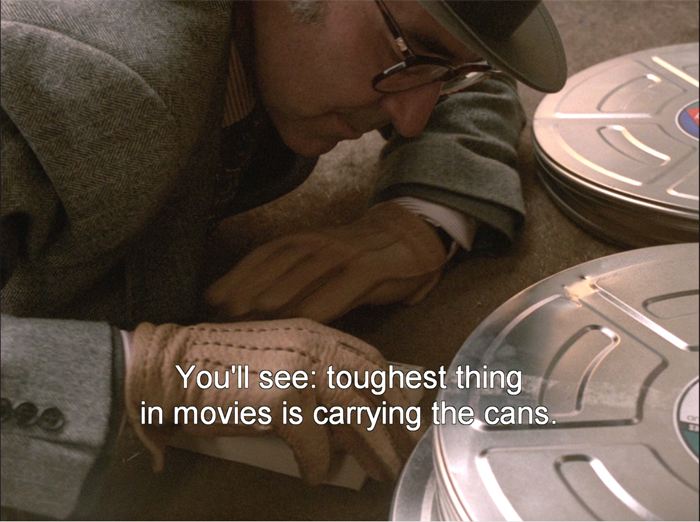

The demiurgic filmmaker can’t leave any picture alone. And of course his voice will guide the soundtrack. Other auteurs have a discreet signature; Professor Pluggy, thanks to all those RCA cables, gives us incessant audio graffiti.

For me the triumphs of the late career are the narrative features. Just as the early films deformed norms of classical storytelling, these can be taken as a continuing dialogue with contemporary “art cinema,” that psychologically-driven filmmaking that explores characters’ minds and relationships. While art-cinema narration sometimes challenges the viewer, Godard goes much further.

Again, story entices us. The late films return to situations he has long relied on, usually involving a romantic couple but sometimes also a family, as in the second section of Film Socialisme. There are recurring arcs of action: seduction and courtship, a dissolving couple, an investigation, or an artistic project–recording a song, making a film. There will be at least one long conversation, but also communication through body language, often violence.

The milieu is often that of a workplace–a factory or business, especially that of prostitution or filmmaking. (Passion makes the film studio a parallel setting to the factory.) Godard once said that the most important things in life are love and work, and these concerns supply his late works’ narratives with a recognizable world.

He sometimes provides “braided” plots, tracing two or or more groups of characters, parallel or intersecting. For Ever Mozart bears the label “36 Characters in Search of History.” Such braiding is comparatively rare in his early period. The plot will be partitioned by chapter divisions, but they don’t necessarily mark off portions of a story; just as often they interrupt a scene. Instead of braiding, we may get a sort of geometry, with two or three side-by-side stories–leaving us to sense connections among them. As the late career progresses, I think that those connections become more elusive.

Once we have narrative conventions in place, they can be blocked. Reviewers who confidently sum up a Godard plot don’t do justice to Godard’s astounding resourcefulness in impeding our understanding while still teasing us to try to get it. If the early films interrupt the action, in the later films we have trouble figuring out what the action is.

Bereft of point-of-view shots, visualized memories and dreams, appointments, and deadlines, these films avoid the commonplaces of modern movie storytelling. In that sense his films are “objective” in relying on characters’ behaviors to convey the action. But that behavior is often difficult to understand.

The characters may be unidentified, or inconsistent, or unrealistic in their actions and reactions. Why does the factory boss in Passion carry a rose in his teeth? Where does the twin of Alain Delon come from in Nouvelle Vague? On first seeing Hélas pour moi, I found every image ravishing and every scene baffling.

The most basic exposition about the characters’ relationships is often suppressed. Often you must watch the film several times to figure out kinship and alliances because there is only one hint, not the redundant signaling we get in mainstream cinema. And even when we’ve sorted out the characters’ roles, a scene may not have a clear-cut arc. We might enter the action partway through and leave it before the scene ends.

Part of the difficulty comes from an idiosyncratic style. He favors “troubled” master shots. The action is given a kind of coverage, but with obscure angles, partial framings, and time gaps between shots (alternatively, repetitions of dialogue). The editing of a scene often relies on the Kuleshov effect, with shots of single characters linked through eyelines.

Overall, a scene’s presentation is both sparse and dense. The action is built out of details, but sometimes things get overbusy, with jammed frames and layers of dialogue. And he loves to block our view of faces, by using the frame to decapitate major characters, or to interpose objects that make it hard to understand who’s present, or to tuck faces into apertures.

More blockage: main characters are often turned from us, plunged into shadow, or put out of focus, making expressions difficult to read. Combined with depth staging, these shots challenge us to carve out the prime narrative action (Passion, Éloge de l’amour, Notre musique).

Refusing the Steadicam (and today’s annoying slow track-ins to a character), Godard locks down the camera. He moves his figures through the shot and insists on filling the 1.37 ratio: every zone of space can matter. Any area of the image can harbor a significant gesture or facial expression (Hail Mary, Detective).

Godard’s fastidious attention to the precise image has not prevented him from his characteristic “overwriting” in post-production. The action, inevitably, is interrupted by intertitles. Classical music or ECM samples drop in and out, with a voice-over elaborating on what we see. Not content to let others supply English subtitles, Godard has lately provided his own, or simply suppressed them during certain stretches of dialogue or voice-over.

One result of this obscurity is to redirect our attention. If we can’t comprehend the full story action, we focus on other things, such as the composition of the image, the interplay of sounds, the expressiveness of the music. Alternatively, the absence of clear-cut scenic structure throws an emphasis onto the texts that his characters obsessively read, cite, and recite. And when we do see clearly, there are the faces, given weight by the shots devoted to them (Notre musique, Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro).

There’s also the historical dimension of the deformations. A Picasso still life asks us to compare it to the classic exemplars of the genre. Similarly, Godard asks us to compare his forms and styles to their precedents. Détective, one of the few late films that hark back to classic Hollywood, proffers a mystery (who killed the Prince two years ago?), investigated by three characters. There’s also suspense, and a deadline for payment during a prizefight. Alongside this noirish premise is a Grand Hotel template juggling several couples and romantic triangles. But this “ensemble film,” packed with opaque shots and fragmented scenes, is far from the trim construction of classical Hollywood.

Similarly, Éloge de l’amour, with its quest to grasp the Holocaust, invites us into an art-cinema investigation plot reminiscent of L’Avventura. But instead of a search for a missing person, we get a dense adventure split into two parts (black and white film, trembling color video) that does what it can to cloud the inquiry, while bringing out a critique of Hollywood’s treatment of history.

“The best criticism of a film is another film.” Taking film history as a conversation among filmmakers, Godard bounces off Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero, Pialat’s Sous le soleil du Satan, and Truffaut’s Man Who Loved Women and Day for Night (below, with Passion).

Late Godard has shadowed Tati with distracting long-shot staging reminiscent of Play Time (here, Hélas pour moi) and has paid homage to him in Soigne ta droite.

Even more pervasive is the invocation of Bresson. With a behavioral narrative, sound that replaces image, and the fragmentation of a scene through partial views, Godard seems to take a perverse “next step” beyond the master. Bresson died during the shooting of Éloge de l’amour, so there’s of course an homage, but more generally the late films’ style often radicalize Bresson’s technique, hands above all (Soigne ta droit, Détective).

Godard’s deformations not only “spoil” his own work but point to fresh possibilities in the traditions of narrative cinema.

Moments

Pierrot le fou (1965).

It’s not enough to note all the ways Godard impairs our comprehension of the story. As critics we need to show how the result can still add up to something coherent, even rigorous. We probably won’t be able to clarify everything, but we can try to show underlying patterns, in the way a critic can show a compositional logic underlying a cubist painting. I’ve tried to do this in two installments of our series on the Criterion Channel and in my analysis of Adieu au langage. Check the codicil to this entry for details.

But even if the overall strategy of disruption remains obscure, there’s a lot to engage us otherwise. Godard has given us scores of shots that no one had ever made before. Here are a few of my favorites, apart from ones I’ve already shown (Une femme mariée, Hail Mary, Made in USA, La Chinoise, Détective).

You have your own, I bet.

Given such shots, you can argue that the Godard narrative has been the bait to lure us into savoring privileged moments of cinema. Is this the heritage of Cahiers cinephilia–Godard’s version of “movie moments” that thrill us through what film (and video) can uniquely do? Or are they a refutation of the overblown CGI of Hollywood, showing what kinds of dazzling imagery can be achieved without special effects?

At any rate, such moments are especially resonant in the context of all the uncertainty. In all, we’re left with an aesthetic of exquisite spoilage. Godard teaches us to sense form underneath deformations, while still making imperfection a ripe artistic pleasure.

My references to Godard’s life are drawn from two excellent career accounts, Richard Brody’s Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (Metropolitan, 2008) and Antoine de Baecque, Godard: Biographie (Grasset, 2010). Brody’s exemplifies what a true “critical biography” should be.

On the Criterion Current, David Hudson compiles links to several Godard tributes. Don’t miss David’s own discerning essay here.

For some years I’d thought of writing a little e-book on Godard, complete with clips. (Why not rip him off as he has done with so many others?) But as I’ve aged I recognized that I’m overmatched. Instead, some entries on this site approach him in bite-size chunks. This piece goes into some detail about his preference for the 4:3 ratio, and how video versions in wider format degrade his compositions. Thoughts about his use of Scope in Le Mépris are elaborated in my Criterion Channel installment of Observations on Film Art. Another Criterion Channel commentary considers the use of the classic ratio in Vivre sa vie. Quick remarks about Le petit soldat are here, based on a visit to Belgium’s Summer Film College. (Visit Cinéa and photogénie to survey the vast number of events and critical studies the College has fostered over the years.)

At another session of the College I offered some ideas about the late films, particularly Nouvelle Vague. (And when will a video version give us the proper 1.37 image for this film? Same goes for Sauve qui peut (la vie) and King Lear.) This entry looks at Godard’s use of Bressonian editing in Hail Mary. Kristin offers a contextual analysis of Film Socialisme, with close consideration of the controversial subtitles. Earlier she took it as an example of the sort of film arthouses should be committed to screening. My comments on that film are here. At the Vancouver film festival KT and I saw 3 x 3D and offered some comments. One entry on Adieu au langage traces some of his 3D tactics, while another considers this film in relation to other late features and offers a detailed analysis of the film’s opening. These essays were revised into the Kino Lorber DVD liner notes.

Soigne ta droit (1987).

Little things

Equinox Flower (Ozu, 1958).

DB here:

Academic critics and fans share a passion for looking closely at the movies we admire. A lot of film critics enjoy spiraling out from the film to ponder Big Ideas, which is okay, I guess. But I confess I particularly enjoy digging in for trouvailles (great word), lucky discoveries that passed me by on earlier encounters.

Across my career, many of the directors I admire seem to have tucked in little things just for me (or you). They don’t necessarily carry meanings; they’re quietly decorative, subtly off-center to the narrative. Tati slipped peculiar items into the corners of the frame. Sturges offered gags that only people with his sense of humor will find funny. A successful crowdsourcing enterprise exposed Welles’ homages to early film. Above all, Ozu nudged me toward red teakettles and surprising details. Who else lines up the levels of beverages in a table setting, and then matches that plane to the edge of a fruit bowl?

If you care enough about my movie, the director seems to say, I’ll reward you with a trouvaille. Here are two I found recently.

Showing the stitches

Sometimes a trouvaille is a felicity of craft. The director quietly shows off his virtuosity to those in the know. While studying Pulp Fiction for a book I’m finishing, I noticed that Tarantino sets up the ending in a sidelong way.

You’ll remember that the opening shows Honey Bunny and Pumpkin discussing how a restaurant is one of the safest robbery targets. Abruptly they launch an assault on the diner. Then they drop out of the film for a couple of hours.

Very likely we’ve forgotten about them when Jules and Vincent settle down for breakfast in a diner. After discussing the virtues of pork products and the prospects for Jules’ future, Vincent rises to go to the toilet. As he pauses, it’s possible, but not easy, to discern the larcenous couple out of focus in their booth behind him. Given their peripheral status and the centrality of Travolta’s performance, I suspect that almost no one notices them on a first viewing.

Soon after Vincent has left, we’ll hear a repetition of the final bits of the couple’s conversation and we’ll see a replay of their leaping up to announce the robbery. Tarantino has rewarded the sharp-eyed viewer with a slight anticipation of the replay, and a hint at how his film will fold back on its opening sequence.

But this echo is matched by a “pre-echo” during the opening sequence. As Pumpkin and Honey Bunny plan their heist, a close view of her includes a bulky man in a t-shirt walking into the distance.

At this point, a first-time viewer hasn’t been introduced to Vincent, so the t-shirt guy is just part of the scenery. Only in retrospect do we realize that here Tarantino is anticipating, and overlapping, the portion of the robbery that we’ll see in the final moments of the film.

Here the critic/fan is invited to appreciate how carefully made the film is. It’s a quality we don’t sufficiently recognize in Tarantino: a delight in fine-grained formal niceties.

Easter Egg, avant la lettre

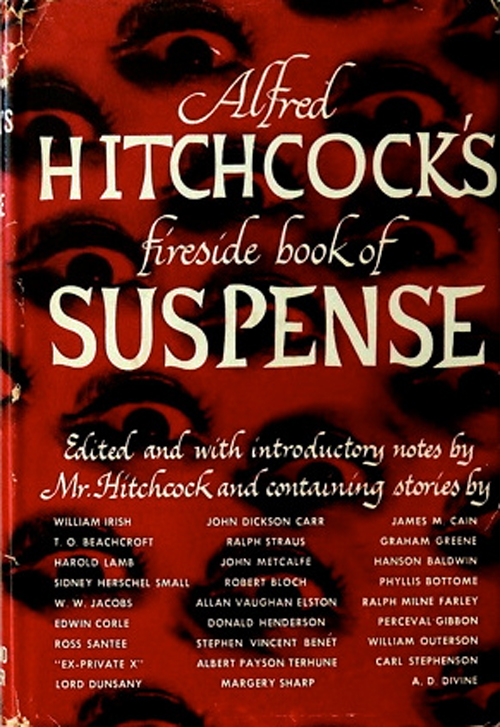

In Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1950), tennis pro Guy Haines is introduced (implausibly) reading a book on his trip. Soon he’s accosted by the spoiled, marginally nuts Bruno Anthony, and the plot gets under way. Only a fan, or a critic, will want to know: What’s Guy reading?

It’s not easy to tell. We don’t get a close-up of the book. The best we can tell, from above, is that it’s a hardcover, with a photo on the back of the dust jacket. Later, after Guy and Bruno have shared a meal in a compartment, we can glimpse the spine.

Blown up, thanks to the glory of Blu-ray, the spine looks like this.

A little research reveals that the volume is Hitchcock’s collection of stories published in 1947 by Simon and Schuster.

Several anthologies were published under Hitchcock’s name from the 1940s onward, but most were in paperback. This was a more prestigious item, and I suspect it helped the branding effort that was underway during his Hollywood career. The picture on the back is of Hitchcock, of course. (My copy lacks a dust jacket, so I can’t supply that.) But the resonance comes from the fact that I was reading this very book as part of preparation for my own study of 1940s mystery culture.

It’s not exactly product placement; the book’s presence is too fleeting to register with audiences, surely. Including the book seems more in the nature of a private joke among Hitch and his team. Guy is a man of good taste, reading a book by the man directing the film he’s in.

Today we’re familiar with Easter Eggs, those bonus materials that establish a complicity between filmmmaker and viewer. Is this an early example? It could be a prize for fan connoisseurship. The book isn’t emphasized, being buried in the mise-en-scene, and so it encourages the devout to poke and probe. It also points outside the film to the production context. Still, how many 1950 viewers, lacking our ability to freeze and magnify the frame, could have spotted it? Perhaps only the devotion of a modern fan, aided by new technology, can bring this trouvaille to light. An incipient Easter Egg, then, awaiting digital technology to be discovered?

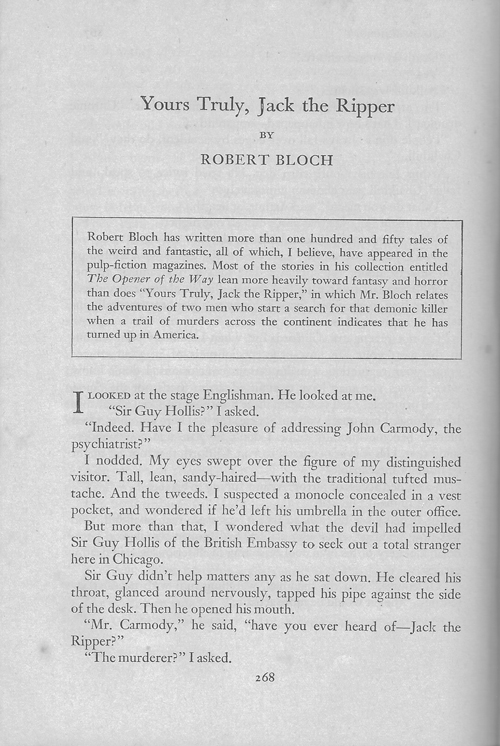

Once we’re down this rabbit hole, let’s scramble further. What stories might Guy be reading? There are two hints. We have the placement of the jacket flap in the shot above, and an earlier shot showing the book open.

As best I can tell, the story Guy’s reading is likely to be “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper.” It tells of a psychiatrist who meets an Englishman called “Guy Hollis.” Sir Guy believes that Jack the Ripper has migrated to the US and is at large in Chicago. With the aid of the psychiatrist, Sir Guy finds him. Apart from the name Guy, the correspondence to Strangers it would seem to involve a peculiar bond between two men, one of whom is a psychopathic killer.

But there’s another, stranger affinity.

The author of “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” is Robert Bloch., whose novel Psycho would furnish Sir Alfred his 1960 film. Coincidence? In the land of trouvailles, are there any coincidences?

Fans have raked over these movies assiduously, so I can’t imagine I’m the first to notice these fine touches. No matter. When you discover them on your own, you still feel a tiny thrill of communicating with the filmmaker, behind the backs of all those folks who didn’t notice. Ozu, I often feel, is making movies especially addressed to me. It’s an illusion, of course, but I refuse to give it up.

Thanks to the University of Wisconsin–Madison Filmies listserv for helping me understand what counts as Easter Eggs, and for a reality check on my sanity.

This site includes lots more on Hitchcock, Ozu, Sturges, and Tarantino. My book on Ozu is available from the University of Michigan. It takes time to download, so be patient.

P.S. 15 August 2021: As I thought, I’m not the first. A mere twenty-one years ago, Dana Polan in his monograph on Pulp Fiction (British Film Institute) noticed the pre-echo of Vincent headed toward the toilet. Good going, Dana! Film analysis wins again.

Days of Youth (Ozu, 1929).

Learning to watch a film, while watching a film

The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992).

DB here:

“Every film trains its spectator,” I wrote a long time ago. In other words: A movie teaches us how to watch it.

But how can we give that idea some heft? How do movies do it? And what are we doing?

Many menus

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (2011).

In my research, I’ve found the idea of norms a useful guide to understanding how filmmakers work and how we follow stories on the screen. A norm isn’t a law or even a rule; it’s, as they say in Pirates of the Caribbean, more of a guideline. But it’s a pretty strong guideline. Norms exert pressure on filmmakers, and they steer viewers in specific directions.

Genre conventions offer a good example. The norms of the espionage film include certain sorts of characters (secret agents, helpers, traitors, moles, master minds, innocent bystanders) and situations (tailing targets, pursuits, betrayal, codebreaking, and the like). The genre also has some characteristic storytelling methods, like titles specifying time and place, or POV shots through binoculars and gunsights.

But there are other sorts of norms than genre-driven ones. There are broader narrative norms, like Hollywood’s “three-act” (actually four-part) plot structure, or the ticking-clock climax (as common in romcoms and family dramas as in action films). There are also stylistic norms, such as the shoulder-level camera height and classic continuity editing, the strategy of carving a scene into shots that match eyelines, movements, and other visual information.

Thinking along these lines leads you to some realizations. First, any film will instantiate many types of norms (genre, narrative, stylistic, et al.). Second, norms are likely to vary across history and filmmaking cultures. The norms of Hollywood are not the same as the norms of American Structural Film. There are interesting questions to be asked about how widespread certain norms are, and how they vary in different contexts.

Third, some norms are quite rigid, as in sonnet form or in the commercial breaks mandated by network TV series. Other norms are flexible and roomy (as guidelines tend to be). There are plenty of mismatched over-the-shoulder cuts in most movies we see, and nobody but me seems bothered.

More broadly, norms exist as options within a range of more or less acceptable alternatives. Norms form something of a menu. In the spy film, the woman who helps the hero might be trustworthy, or not. The apparent master mind could turn out to be taking orders from somebody higher up, perhaps somebody supposedly on your side. One scene might avoid continuity editing and instead be presented in a single long take.

Norms provide alternatives, but they weight them. Certain options are more likely to be chosen than others; they are defaults. (Facing a menu: “The chicken soup is always safe.”) An action film might present a fight or a chase in a single take (Widows, Atomic Blonde), but it would be unusual if every scene in the film were played out this way. Not forbidden, but rare. Avoiding the default option makes the alternative stand out as a vivid, willed choice.

Very often, critics take most of the norms involved for granted and focus on the unusual choices that the filmmakers have made. One of our most popular entries, the entry on Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, discusses how the film creates a demanding espionage movie by its manipulations of story order, characterization, character parallels, and viewpoint. It isn’t a radically “abnormal” film, but it treats the genre norms in fresh ways that challenge the viewer.

Because, after all, viewers have some sense of norms too. Norms are part of the tacit contract that binds the audience to creators. And the viewer, like the critic, looks out for new wrinkles and revisions or rejections of the norm–in other words, originality.

Picking from the menu

Norms of genre, narrative, and style are shared among many films in a tradition or at a certain moment. We can think of them as “extrinsic norms,” the more or less bounded menu of options available to any filmmaker. By knowing the relevant extrinsic norms, we’re able to begin letting the movie teach us how to watch it.

The process starts early. Publicity, critical commentary, streaming recommendations, and other institutional factors point up genre norms, and sometimes frame the film in additional ways–as an entry in a current social controversy (In the Heights, The Underground Railroad), or as the work of an auteur. You probably already have some expectations about Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch.

Then, as we get into the film, norms quickly click into place. The film signals its commitment to genre conventions, plot patterning, and style. At this point, the film’s “teaching” consists largely of just activating what we already know. To learn anything, you have to know a lot already. If the movie begins with a character recalling the past, we immediately understand that the relevant extrinsic norm isn’t at that point a 1-2-3 progression of story events, but rather the more uncommon norm of flashback construction, which rearranges chronology for purposes of mystery or suspense. Within that flashback, though, it’s likely that the 1-2-3 default will operate.

As the film goes on, it continues to signal its commitment to extrinsic norms. An action scene might be accompanied by a thunderous musical score, or it might not; either way, we can roll with the result. The characters might let us into their thinking, through voice-over or dream sequences, or we might, as in Tinker, Tailor, be confronted with an unusually opaque protagonist whose motives are cloudy. The extrinsic norms get, so to speak, narrowed and specified by the moment-by-moment working out of the film. Items from the menu are picked for this particular meal.

That process creates what we can call “intrinsic norms,” the emerging guidelines for the film’s design. In most cases, the film’s intrinsic norms will be replications or mild revisions of extrinsic ones. For all its distinctiveness, in most respects Tinker, Tailor adheres to the conventions of the spy story. And as we get accustomed to the film’s norms, we focus more on the unfolding action. We’ve become expert film watchers. We learn quickly, and our “overlearned” skills of comprehension allow us to ignore the norms and, as we stay, get into the story.

Narration, the patterned flow of story information, is crucial to this quick pickup. Even if the film’s world is new to us, the narration helps us to adjust through its own intrinsic norms. The primary default would seem to be “moving spotlight” narration. Here a “limited omniscience” attaches us to one character, then another, within a scene or from scene to scene. We come to expect some (not total) access to what every character is up to.

In Curtis Hanson’s Hand That Rocks the Cradle, we’re initially attached to the pregnant Claire Bartel, who has moved to Seattle with her husband Michael and daughter Emma. When Claire is molested by her gynecologist Dr. Mott, she reports him. The scandal drives him to suicide, and his distraught wife miscarries. She vows vengeance on Claire. Thereafter, the plot shuttles us among the activities of Claire, Mrs. Mott, Michael, the household handyman Solomon, and family friends like Michael’s former girlfriend Marlene. The result is a typical “hierarchy of knowledge”–here, with Claire usually at the bottom and Mrs. Mott near the top. We don’t know everything (characters still harbor secrets, and the narration has some of its own), but we typically know more about motives, plans, and ongoing action than any one character does.

More rarely, instead of a moving spotlight, the film may limit us to only one character’s range of knowledge. Again, scene after scene will reiterate the “lesson” of this singular narrational norm. That repetition will make variations in the norm stand out more strongly. Hitchcock’s North by Northwest is almost completely restricted to Roger Thornhill, but it “doses” that attachment with brief asides giving us key information he doesn’t have. Rear Window and The Wrong Man, largely confined to a single character’s experience, do something similar at crucial points.

Sometimes, however, a film’s opening boldly announces that it has an unusual intrinsic norm. Thanks to framing, cutting, performance, and sound, nearly all of Bresson’s A Man Escaped rigorously restricts us to the experience of one political prisoner. We don’t get access to the jailers planning his fate, or to men in other cells–except when he communicates with them or participates in communal activities, like washing up or emptying slop buckets.

The apparent exception: The film’s opening announces its intrinsic norm in an almost abstract way. First, we get firm restriction. There are fairly standard cues for Fontaine’s effort to escape from the police car that’s carrying him. Through his optical POV, we see him grab his chance when the driver stops for a passing tram.

The film’s title and the initial situation let us lock onto one extrinsic norm of the prison genre: the protagonist will try to escape. Knowing that we know this, Bresson can risk a remarkable revision of a stylistic norm.

Fontaine bolts, but Bresson’s visual narration doesn’t follow him. The camera stays stubbornly in the car with the other prisoner while Fontaine’s aborted escape is “dedramatized,” barely visible in the background and shoved to the far right frame edge. He is run down and brought back to be handcuffed and beaten.

The shot announces the premise of spatial confinement that will dominate the rest of the film. The narration “knows” Fontaine can’t escape and waits patiently for him to be dragged back. In effect, the idea of “restricted narration” has been decoupled from the character we’ll be restricted to. This is the film’s first, most unpredictable lesson in stylistic claustrophobia.

Got a light?

Most intrinsic norms aren’t laid out as boldly as the opening of A Man Escaped, but ingenious filmmakers may provide some variants. Take a fairly conventional piece of action in a suspense movie. A miscreant needs to plant evidence that incriminates some innocent soul.

In Strangers on a Train, that evidence is a cigarette lighter. Tennis star Guy Haines shares a meal with pampered sociopath Bruno Antony, whose tie sports colorful lobsters. Bruno steals Guy’s distinctive cigarette lighter.

Bruno has proposed that they exchange murders: He will kill Guy’s wife Miriam, who’s resisting divorce, and Guy will kill Bruno’s father. Bruno cheerfully strangles Miriam at a carnival, aided by the lighter.

When Guy doesn’t go through with his side of the deal, Bruno resolves to return to the scene of Miriam’s death and leave the lighter to incriminate Guy. The film’s climax consists of the two men fighting on a merry-go-round gone berserk. Although Bruno dies asserting Guy’s guilt, the lighter is revealed in his hand. Guy is exonerated.

Once the lighter is introduced in the early scenes, it comes to dominate the last stretch of the film. In scene after scene, Hitchcock emphasizes Bruno’s possession of it. Sometimes it’s only mentioned in dialogue, but often we get a close-up of it as Bruno looks at it thoughtfully–here, brazenly, while Guy’s girlfriend Ann is calling on him.

When Bruno picks up a cheroot or a cigarette, we expect to see the lighter.

One of the film’s most famous set-pieces involves Bruno straining to retrieve the lighter after it has fallen through a sidewalk grating.

Bruno has dropped it before, during Miriam’s murder, but then he notices and retrieves it. It’s as if this error has shown him how he might frame Guy if necessary. The image of the lighter in the grass previews for us what he plans to do with it later.

What does the lighter have to do with norms? Most obviously, Strangers on a Train teaches us to watch for its significance as a plot element. It’s not only a potential threat, but also Bruno’s intimate bond to Guy, as if Bruno has replaced Ann, who gave Guy the lighter. The film also invokes a normalized pattern of action–a character has an object he has stolen and will plant to make trouble–and treats it in a repeated pattern of visual narration. The character looks at the object; cut to the object; cut back to the character in possession of the object, waiting to use it at the right moment. Our ongoing understanding of the lighter depends on the norm-driven presentation of it.

Once we’re fully trained, Hitchcock no longer needs to show us the lighter at all. En route to the carnival to plant the lighter, Bruno lights a cigarette with the lighter, although his hands conceal it. But then the train passenger beside him asks for a light.

In order to hide the lighter, Bruno laboriously pockets it and fetches out a book of matches.

If we saw only this scene, we might not have realized what’s going on, but it comes long after the narrational norm has been established. We can fill out the pattern and make the right inference. Bruno wants no witness to see this lighter.

The hand that cradles the rock

In The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, under the name Peyton Flanders, Mrs. Mott becomes nanny to Claire’s daughter and infant son. Pretending to be a friendly helper, she subverts Claire’s daily routines and her trusting relationship with Michael. As in most domestic thrillers, the accoutrements of upper-middle-class lifestyle–a baby monitor, a Fed Ex parcel, expensive cigarette lighters, asthma inhalers, wind chimes–get swept up in the suspense. Peyton weaponizes these conveniences, and through a somewhat unusual narrational norm the film trains us to give her almost magical powers.

We get Peyton’s early days in household filtered through her point of view. Classic POV cutting is activated during her job interview. She notices that Claire’s pin-like earring drops off and she hands it back to her.

Attachment to Peyton gets more intense when she sees the baby monitor and then fixates on the baby.

We’re then initiated into her tactics, and to the film’s way of presenting them. Serving supper, Claire doesn’t notice that her earring drops off again. Peyton does.

Breaking with her POV, the narration shifts to Claire and Michael talking about hiring her. But this cutaway to them has skipped over a crucial bit of action: Peyton has picked up the earring. Unlike Hitchcock, director Curtis Hanson doesn’t give us a close-up of the important object in the antagonist’s hand. In a long shot we simply see Peyton studying her fingers. Some of us will infer what she’s up to; the rest of us will have to wait for the payoff.

After another cutaway to the couple, Peyton “discovers” the earring in the baby’s crib. Her show of concern for his safety seals the hiring deal and begins her long campaign to prove that Claire is an unfit mother.

This elliptical presentation of Peyton’s subterfuges rules the middle section of the film. Selective POV shots suggest what she might do, but we aren’t shown her doing it–only the results. For instance, Claire lays out a red dress for a night out. Peyton sees it, then sees some perfume bottles.

Cut to Claire and then to an arriving guest, and presto. When she returns to the mirror, her dress is suddenly revealed as having a stain.

Later, Claire agrees to send off Michael’s grant application during her round of errands. Once she gets to the Fed Ex office, she will discover the missing envelope. Before that, though, we get another variant of the intrinsic norm showing Peyton’s trickery.

In the greenhouse, while Claire is watering plants, Peyton spots the envelope in her bag. We don’t see her take it, and there’s even a hint that she hasn’t done so. A nifty shot lets us glimpse her yanking her arm away as Claire approaches. It’s not clear that she has anything in her hand.

In what follows, the narration confirms Peyton’s theft while building up the threat level.

If she’s caught, this woman will not go away quietly.

While cozying up to the children–Peyton cuddles with Emma and even secretly breast-feeds baby Joe–Peyton eliminates all of Claire’s allies. By now we know her strategy, so after she suggests to Claire that the handyman Solomon has been molesting little Emma, all the narration needs is to show us Claire discovering a pair of Emma’s underwear in his toolbox. As with Bruno’s pocketing the lighter in Strangers on a Train, we’re now prepared to fill in even more of what’s not shown: here, Peyton framing Solomon.

Michael, a furtive smoker, sometimes shares a cigarette with Marlene. So it’s easy for Peyton to plant Marlene’s lighter in Michael’s sport coat for Claire to discover. Again, the moment of the theft has given her quasi-magical powers. She sees Marlene’s lighter in her handbag in the front seat.

Again thanks to a cutaway, we don’t see her take it. Indeed, it’s hard to see how she could have; she comes out of the back seat with an armload of plants.

But later Marlene will tell Michael (i.e., us) that she’s lost her lighter, and a dry cleaner will find it and show it to Claire.

The attacks have escalated, with Claire now suspecting Michael of infidelity. She confronts him without knowing that Michael has invited friends to a surprise party for her. Her angry accusations are overheard by the guests, and this public display of her anxieties takes her to a new low.

Peyton’s revenge plan is almost wholly consummated, so we stop getting the elliptical POV treatment of her thefts. Instead, the plot shifts to investigations: first Marlene discovers Peyton’s real identity, with unhappy results, and at the climax Claire does. Her POV exploration of the empty Mott house counterbalances Peyton’s early probing of Claire’s household. When she sees Mrs. Ott’s breast pump–another domestic object now invested with dread–she realizes why baby Joe no longer wants her milk.

This is the point, fairly common in the thriller, when the targeted victim turns and fights back.

In The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, a familiar action scheme–someone swipes something and plants it elsewhere–is handled through an unusual narrational norm. The scenes showing Peyton’s pilfering skip a step, and they momentarily let us think like her, nuts though she is. Thanks to editing that deletes one stage of the standard shot pattern, the film trains us to see how banal domestic items, deployed as weapons, can destroy a family. In the course of learning this, maybe the movie makes us feel smart.

Arguably, we’re able to fill in the POV pattern in The Hand That Rocks the Cradle because we’ve learned from encounters with movies that used the standard action scheme, including Strangers on a Train. This is one reason film style has a history. Dissolves get replaced by fades, exposition becomes more roundabout, endings become more open. As audiences learn technical devices, intrinsic norms recast extrinsic ones and some movies become more elliptical, or ambiguous, or misleading. All I’d suggest is that we get accustomed to such changes because films teach us how to understand them. And we enjoy it.

The passage about training us comes from my Narration in the Fiction Film (University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 45. I discuss norms in blog entries on Summer 85, on Moonrise Kingdom, on Nightmare Alley, and elsewhere. A book I’m finishing applies the concept to novels as well as films.

The example of mismatched reverse angles comes from The Irishman (2019) In the first cut, Frank is starting to settle his coat collar, but in the second, his arms are down and the collar is smooth. In a later portion of that second shot, Hoffa gestures freely with his right hand, but in the over-the-shoulder reverse, his arm is at his side and it’s Frank who gets to make a similar gesture. To be fair, I should say that I found some striking reverse-angle mismatches in Strangers on a Train too.

For more on conventions of the domestic thriller, go to the essay “Murder Culture.”

Radomir D. Kokeš offers an analysis of how Kristin and I have used the concept of norm. We are grateful for his careful discussion of our work and his exposition of the achievement of literary theorist Jan Mukarovský. See “Norms, Forms and Roles: Notes on the Concept of Norm (not just) in Neoformalist Poetics of Cinema,” in Panoptikum (December 2019), available here.

Strangers on a Train (1951).

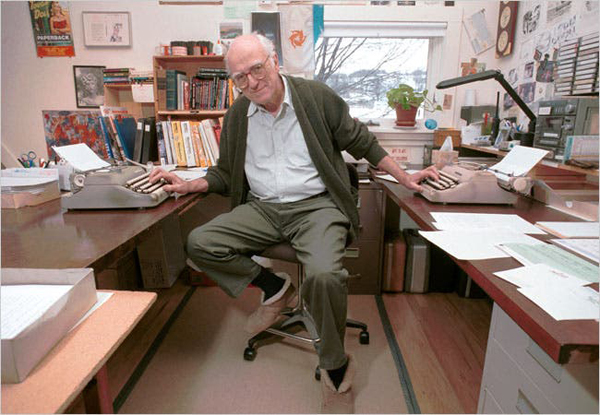

Five critics, one of them a killer

Goodfellas (1990).

DB here:

Fourteen months of being house-bound gave me plenty of chance to catch up on my reading. But the reading was almost all devoted to the book I was writing on mystery plots in fiction, film, and other media. Now that it has been catapulted out to unwary publisher’s readers, it’s time for me to catch up on some 2020 books I like. In this batch, all have a connection to film criticism, and murder, attempted or consummated, creeps into more than one.

Movies for Muggles

Somebody ought to write a history of the one-movie monograph. Early on there were picture books, and roadshow attractions often produced pretty laminated books as souvenirs, filled with PR stories and color images. My vote for the first analytical monograph would be the very ambitious Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima! (1962). In the early 1970s, American academic presses began offering critical studies of single films; an early example was the FilmGuide series edited by Harry Geduld and Ron Gottesman. (My favorite entry was Jim Naremore‘s study of Psycho.) Since then many publishers have pursued the format, usually as part of a series.

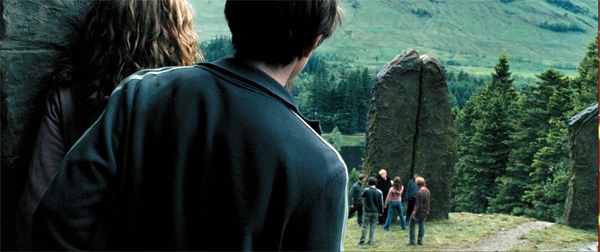

Now we have 21st Century Film Essentials, newly launched at the University of Texas Press. The first two entries are pretty canon-busting. Dana Polan writes on The Lego Movie, and Patrick Keating on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. I haven’t seen Polan’s book, but Keating directly takes up the challenge of the series.

As a franchise film, as a work of digital cinema, as a work of collaborative authorship, and above all as a thoroughly engaging demonstration of the art of storytelling, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is an essential work of twentieth-first century cinema.

I confess I was skeptical, and still am a little. But Keating’s meticulous analysis and interpretation of the film does convince me that this is a ripe example of modern “hyperclassical” cinema. By that I mean a dense, “through-composed” revision of traditional narrative strategies and film techniques, working smoothly together to create effects at many levels. A hyperclassical film is more thoroughly classical than it “needs to be.” In other words, here’s another counterexample to the notion that “post-classical Hollywood” shows a collapse of traditional norms.

I confess I was skeptical, and still am a little. But Keating’s meticulous analysis and interpretation of the film does convince me that this is a ripe example of modern “hyperclassical” cinema. By that I mean a dense, “through-composed” revision of traditional narrative strategies and film techniques, working smoothly together to create effects at many levels. A hyperclassical film is more thoroughly classical than it “needs to be.” In other words, here’s another counterexample to the notion that “post-classical Hollywood” shows a collapse of traditional norms.

Keating’s argument for the film’s richness, I think, revolves around two central concepts. First is that of narrative viewpoint. Virtually all of Azkaban, unlike the earlier entries in the franchise, is filtered through the consciousness of Harry. We’re attached to him as he experiences the action. That doesn’t, Keating hastens to add, make the film radically subjective; indeed, there are relatively few shots from Harry’s optical viewpoint. Attaching the unfolding plot to a character doesn’t rule out a wider perspective, if only because cinema puts him within a wider frame of a shot or an edited sequence. There’s always the possibility of our registering action or other characters’ reactions. The end of the Quidditch flight is thick with these impacted viewpoints, and elsewhere Cuarón’s constantly moving camera nudges us toward implications that supplement, or sometimes contradict, what Harry is concentrating on.

Keating’s other main concept is connected to the broadening of viewpoint: worldbuilding. This idea is obviously central to Rowling’s achievement, as it has been to franchises since Star Wars. But Keating lifts the idea to a central role in how films engage us. The richly realized world of Potter is only an extreme instance of what every narrative does. Borrowing from critic V. F. Perkins, Keating suggests that any film narrative supplies us with the possibility of many stories that are only hinted at, or merely latent.

Most movies prune those secondary offshoots, the better to force us to concentrate on our protagonist. But Tom Stoppard showed that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern deserved their own play. Similarly, franchise films, with the ever-present prospect of sequels, crossovers, or reboots, make us aware that any character, even any item of furniture, secretes a new story, or a bunch of them. The Potter films are committed to this spinoff aesthetic, packing in as many suggestions of sidestories as the screen will bear. This principle finds tangible expression in the portraits jammed into the Gryffindor common room and dorms guarded by the Fat Lady.

Overwhelming us with characters and situations, many in motion, this gallery is perfectly in keeping with English traditions of floor-to-ceiling decor. It’s also a groaning feast of other stories that could yet, somehow, intersect with Harry’s fate. Keating’s shrewd commentary on worldmaking is one of the book’s highlights.

Keating ties these ideas to phases of production and division of labor, reviewing how the novel’s viewpoint and worldbuilding strategies are transposed and extended by script, camerawork, editing, performances, set and costume design, and music. Throughout he weaves what he takes to be the film’s binding theme, that of time. Is the future preordained, as Ms. Trelawney insists in her frantic, fumbling lectures? Or is it open, as Hermoine and others tell Harry? This makes the film’s tour de force climax with the Time Turner into a synthesis of restricted viewpoint (we’re with Harry as he witnesses an alternative future) and worldbuilding (the future is what you make it).

I might quarrel with Keating’s suggestion that the impulse driving Harry’s action is a struggle with the dementers. I saw his relation to Sirius Black as more than the subplot Keating considers it. Overall, though, Keating has produced not only a subtle, supple analysis of the film but also a model for how to understand cinematic storytelling in the age of the blockbuster.

Wiseguy’s progress

If Keating’s book is a classical sonata, Glenn Kenny’s Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas is bop. Keating offers a tidy analysis through crisply defined categories. Kenny provides a hardcopy approximation to a packed DVD.

At the center is a 150 page scene-by-scene account of the film: a commentary track in your hands. Alongside that sit chapters that function as bonus materials. They include a brief introduction to the filmmaker just before he started work on the film, chapters on preproduction, the music (Kenny is an expert on pop and rock), the editing, the critical reception, and the ultimate fate of the real-life protagonist Henry Hill. Then, like the narrator of a Criterion video supplement, Kenny surveys Scorsese’s career after Goodfellas. Finally, an epilogue is virtually a monologue: Scorsese talks almost without interruption for twenty-five pages, as if this were the interview rounding off the disc. There’s also a bibliography, a timeline of the production, and the recipe for Henry Hill’s ziti.

At the center is a 150 page scene-by-scene account of the film: a commentary track in your hands. Alongside that sit chapters that function as bonus materials. They include a brief introduction to the filmmaker just before he started work on the film, chapters on preproduction, the music (Kenny is an expert on pop and rock), the editing, the critical reception, and the ultimate fate of the real-life protagonist Henry Hill. Then, like the narrator of a Criterion video supplement, Kenny surveys Scorsese’s career after Goodfellas. Finally, an epilogue is virtually a monologue: Scorsese talks almost without interruption for twenty-five pages, as if this were the interview rounding off the disc. There’s also a bibliography, a timeline of the production, and the recipe for Henry Hill’s ziti.

It’s overwhelming. Kenny has evidently read everything about the real-life sources of the story, and his interviews turn fan service toward crime reporting. It is no small thing to pursue hard cases who were recruited for bit parts. Kenny has also garnered a lot of information from staff like AD Joseph Reidy, who are seldom given much attention. Keating would probably be happy to see Kenny’s narrative splinter into stories leading to other stories, such as the effects of the film on the careers of Barbara De Fina and Ileanna Douglas.

I compared the book’s central chapter to a DVD commentary. Anybody delivering a voice-over play-by-play regrets that you have to keep up with the film and can’t devote as much time to a big scene as you might like. Thanks to the print format, Kenny is able to pause the film and spiral out from it to fill in backstory or behind-the-scenes dynamics.

Early on, he can give us three pages on Tuddy, both his original (who died in prison) and Frank DiLeo, the actor playing the role. Kenny explains that DiLeo was a music executive who oversaw Michael Jackson’s “Bad” video, which included a Wanted poster of Scorsese in a subway scene, which ties to a sneaky reference to the “Smooth Criminal” video featuring a character named Frank Lideo, played by Joe Pesci. . . well, you get the idea. Likewise, in an astonishing cadenza, Kenny identifies every actor and wiseguy in the long POV tracking shot in the Bamboo Lounge.

His account of the cast rummages through filmographies and personal histories, and adds the sort of oversharing we welcome: “Behind the placid mook mug seen in the movie was a remorseless killer.”

All these exfoliating tales don’t conceal a sustained performance of film criticism. Kenny’s governing idea is that Goodfellas cons us through a bait and switch. Lured in by a rapid-fire opening that arouses a bemused attraction to these bad boys, we’re gradually forced to a more sober, even horrified, realization of their moral and emotional brutality. I think that this fairly reflects most viewers’ experience. But how does the trap work?

Kenny plots an “arc of disengagement” between the killings of Tommy and Spider. A rise-and-fall pattern links the parallel scenes of the Bamboo Lounge, the Copacabana, and the shabby tavern where the gang meets to whack Morrie. Kenny draws nuanced comparisons with The Godfather and is very detailed on Scorsese’s visual techniques, particularly the freeze-frames and fadeouts, which usually get less attention than the flashy camera moves. One of the book’s main points is that Scorsese, newly aware of how TV commercials trained viewers in quick pickup, deliberately decided to make his fastest-paced movie. And of course the music is central to managing our mood and commenting on the story.

As a seasoned reviewer, Kenny can write. “Frisky newlyweds still hot for each other; you love to see it.” Henry (“a walking appetite”) eventually pulls Karen into his schemes: “The revitalized marriage will find its sense of twisted teamwork.” And digression is welcome when it humanizes the author. Listening to Sid Vicious’ version of “My Way” is comparable to “say, eating the fried chicken from the Kansas City restaurant Stroud’s for the first time.” (The “say” makes the sentence.) A movie about food begs the critic to sample a little synaesthesia, with music evoking mouth-watering chicken. Come to think of it, that linkage of music and food is in Goodfellas too.

I especially enjoyed Kenny’s rebuke to fans who bust this carefully constructed work into “movie moments.” You probably know that one school of criticism thinks that films are more or less loose assemblages of scenes, out of which certain instants become incandescent. Certainly there are such moments in many movies, and sometimes they stand out from a gray pudding. But often strong moments ravish us because they’ve been prepared for by careful craft. So Kenny’s guided tour of Goodfellas shows its affinities with Keating’s holistic approach:

Serrano and his crew reduce movies to anthologies of “cool” or shocking moments, as opposed to fictions whose circumscribed worlds aspire to create beauty or sorrow or horror or joy in some formally coherent whole.

Mon semblable, mon frère.

Dead end at the ocean’s edge

La La Land (2016).

On the other hand, I ought to be out of sympathy with Mick LaSalle’s Dream State: California in the Movies. It’s unabashedly reflectionist, tracing how films project contradictory images of the Golden State. The screen image of California promises pure self-fulfillment, but that leads to loneliness, danger, conformity, and loss of dignity. If Kenny and Keating see movies as made by an army of artisans, LaSalle treats them as springing full-blown from American mythology. There is barely a mention of a director, let alone a sound mixer, in his account.

Instead, California-ism makes its way to the screen through a surge of a “collective mentality.” For instance, the blockbusters’ endless images of urban annihilation spring from “a people disseminating and celebrating visions of their own obliteration. . . . Something is seriously wrong with the nation producing such visions.” He suggests that “the fear of extraterrestrials is the disguised fear of illegal aliens. . . . the fear of the apocalypse is the disguised fear of terrorism.” Hollywood takes dictation from mass anxieties.

Instead, California-ism makes its way to the screen through a surge of a “collective mentality.” For instance, the blockbusters’ endless images of urban annihilation spring from “a people disseminating and celebrating visions of their own obliteration. . . . Something is seriously wrong with the nation producing such visions.” He suggests that “the fear of extraterrestrials is the disguised fear of illegal aliens. . . . the fear of the apocalypse is the disguised fear of terrorism.” Hollywood takes dictation from mass anxieties.

I’ve explained elsewhere (here and here) why I find such claims unpersuasive. I think that reflectionism is every smart person’s mistaken idea about cinema. But sometimes, as with Susan Sontag’s essay “The Imagination of Disaster,” a reflectionist account of a film can activate some valuable ideas and information along the way, and it can host some entertaining writing. These benefits, I think, emerge throughout Dream State. In kaleidoscopic bursts, LaSalle provides suggestive takes on movies familiar and obscure, and the way they link to one another.

For example, he tracks recurring plot patterns. There’s California’s version of the One Great Night, when individual transformation takes place in a few hours of turbid activity (Superbad, Modern Girls). American Graffiti is the prototype, and in just two pages LaSalle evokes the way audience knowledge races ahead of the characters, far into the future. (Curt winds up in Canada, which probably has to be explained to young viewers today.)He’s very good on the cost-of-stardom plot, from What Price Hollywood to La La Land, this last the only film that faces the fact “that every great advance requires sacrifice, and that even though there is nothing like the joy of first love , there is nothing more important than the fulfillment of one’s inner self.”

LaSalle considers our willingness to take stars as surrogates for us, and here I was reminded of another critic who tried to pierce the Hollywood Hallucination, the great Parker Tyler. He had, I think, a more meta attitude toward the movies, since he avoided straight reflectionism by treating every film as a charade, a narcissistic exercise in make-believe. For Tyler, Hollywood movies were always primarily about Hollywood, filled with symbolic surrogates for their makers and their viewers. In this respect, LaSalle’s opening chapter is agreeably Tyleresque, positing The Wizard of Oz as a film enacting the flight to a dream city; the Emerald City as Hollywood. Like Tyler as well, LaSalle searches for what he calls a movie’s complex finish, as with a glass of wine. Wizard ends not on a note of ambiguity exactly, but on something like a chord that sets off contrary overtones. Tyler’s books were built on this chord.

LaSalle considers our willingness to take stars as surrogates for us, and here I was reminded of another critic who tried to pierce the Hollywood Hallucination, the great Parker Tyler. He had, I think, a more meta attitude toward the movies, since he avoided straight reflectionism by treating every film as a charade, a narcissistic exercise in make-believe. For Tyler, Hollywood movies were always primarily about Hollywood, filled with symbolic surrogates for their makers and their viewers. In this respect, LaSalle’s opening chapter is agreeably Tyleresque, positing The Wizard of Oz as a film enacting the flight to a dream city; the Emerald City as Hollywood. Like Tyler as well, LaSalle searches for what he calls a movie’s complex finish, as with a glass of wine. Wizard ends not on a note of ambiguity exactly, but on something like a chord that sets off contrary overtones. Tyler’s books were built on this chord.

Another critical avenue that LaSalle opened up for me was iconographic: the differences between LA movies and San Francisco movies. He deftly contrasts the ambience and topography of the cities. Noir and disaster films are primarily anchored in LA, while San Franciso movies tend to be steeped in nostalgia (e.g., Jobs, Milk). He keeps finding new angles to comment on. Avoiding the obvious effort to discuss California’s boom during and after the war, he skips back to the months around Pearl Harbor to bring to light films, mostly exploitation quickies like Secret Agent of Japan and Little Tokyo, USA, that rushed to treat Japanese Americans as potential spies. Meanwhile, the unoffending citizens were shipped off to internment. On a lighter note, anybody who’s bold enough to praise Gidget as a more mature film than Easy Rider gets my admiration (and agreement).

LaSalle, who came to California from the east, weaves in bits of memoir that highlight his main theme. And like Kenny, he writes with conversational wit.

“Home is horrible. Oz is horrible, too. . . but at least it’s in color.”

On Saturday Night Fever and Grease: “One seems tough, but it’s soft. (Of course, that’s the New York film.) One seems soft, but it’s hard. (Of course, that’s the Los Angeles film.)”

In Hollywood “integrity is so original it might just work as a strategy.”

In Out of the Past, “sex can kill you, but it’s worth it anyway.”

In San Francisco (1936) “if only to get Jeanette MacDonald to stop singing, the Earth had to intervene.”

Contrasting Monterey Pop to Woodstock‘s utopian fantasy, LaSalle nearly had me on the floor.

This is a model? Hundreds of thousands of intoxicated people, unable to wash, all but sitting in their own slop, cheering for a series of aristocrats that swoop down to entertain them and then leave? Meanwhile, the army flies in food and the slave classes clean out the Port-O-Sans? That’s sustainable as a societal model?

In addition to all this, through engaging appreciation, LaSalle has prompted me to seek out a great many films I hadn’t heard of. That’s another duty of the good critic. After seeing so much–pounding the beat every day–the movie reviewer can steer you to new discoveries.

Cinephile into cineaste and back again

He Said, She Said (1991).

All of these critics have participated in filmmaking. Mick LaSalle has written and produced documentaries. Glenn Kenny has been an actor in several films (including Soderbergh’s Girlfriend Experience). Patrick Keating, who has an MFA in cinematography, has been a DP on independent projects. Reciprocally, director Ken Kwapis started out wanting to be a film critic–in third grade, no less.

In college he devoured classic movies and gorged on film criticism. Kwapis went on to become a director of consequence, overseeing many features (Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, He’s Just Not That into You) and TV episodes (The Garry Shandling Show, The Office). Yet he didn’t leave his cinephilia behind. But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct: Lessons from a Life behind the Camera has an intellectual heft rare in career memoirs and moviemaking manuals. It’s at once thoughtful and practical, suffused throughout by an ethic of modesty, tenacity, and what I can only call a desire to remain both a good artist and a decent person. It also contains some first-rate film criticism.

In college he devoured classic movies and gorged on film criticism. Kwapis went on to become a director of consequence, overseeing many features (Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, He’s Just Not That into You) and TV episodes (The Garry Shandling Show, The Office). Yet he didn’t leave his cinephilia behind. But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct: Lessons from a Life behind the Camera has an intellectual heft rare in career memoirs and moviemaking manuals. It’s at once thoughtful and practical, suffused throughout by an ethic of modesty, tenacity, and what I can only call a desire to remain both a good artist and a decent person. It also contains some first-rate film criticism.

Kwapis intercuts three sorts of chapters. There is the chronological account of the filmmaking process, with advice on taking meetings, establishing rapport on the set, giving actors “playable notes,” and coping with postproduction and marketing. Kwapis insists at every turn that you need to be both firm and flexible, open to every suggestion from the production team but still adhering to your conception of the project.

But this is not auteurism on steroids. If you’re not a Spielberg or a Nolan, the director has to learn tact and strategy. Kwapis emphasizes not abstract technique but the interactive, interpersonal demands of filmmaking, He suggests ways of responding to producers’ notes or actors’ complaints that allow everyone to keep their dignity. Just stepping away from the Video Village, that cluster of people around the monitor, and positioning yourself by the lens is a way of proactively steering the scene. He even gives good advice about bad reviews. His creative process? “I want to stand behind the camera and make sure there’s something alive going on in front of it, something recognizably human.”

A second batch of chapters shows this aesthetic/ethos in action through case studies from Kwapis’ career. Starting with Follow That Bird (1985), the Big Bird movie, and running up to A Walk in the Woods (2015), these chapters are about concrete problem-solving. How do you direct puppets? Or orangutans? Or Rip Torn? How do you support an actor who’s just not physically up to the role? There’s a fascinating account of staging options in The Office, where different situations force choices between developing the action in the “bull pen” or in the conference room.