Archive for February 2007

World rejects Hollywood blockbusters!?

(T)Raumschiff Surprise–Period 1

Kristin here—

I’ve just returned from two weeks in Egypt, and on the ten-hour flight from Cairo to New York, I had plenty of time to absorb the contents of the February 24-25 edition of the International Herald Tribune. One of its articles, “Hollywood rides off into the setting sun,” proclaimed the imminent decline of Hollywood.

The co-authors of this article are Nathan Gardels, editor of NPQ and Global Viewpoint, and Michael Medavoy, CEO of Phoenix Pictures and producer of, among many others, Miss Potter. These two are, according to the biographical blurb accompanying the article, writing “a book about the role of Hollywood in the rise and fall of America’s image in the world.”

The Tribune piece is a slightly abridged version of an essay that appeared on The Huffington Post on February 21, 2007 under the title “Hearts and Minds vs. Shock and Awe at the Oscars.” The subject is not really the Oscars, though, but the supposed decline in interest in American blockbusters, both in the USA and abroad. The authors make a series of claims to suggest that Hollywood is about to lose its “century-long” status as the center of world filmmaking. (Actually American films didn’t gain dominance on world markets until early 1915, but that’s a quibble in the face of the other shaky claims made here.)

1. Foreign films are getting all the awards and prestige this year. “Films by foreigners such as ‘Babel,’ ‘The Queen’ and ‘Volver’ that make little at the box office are winning the top awards while the big Hollywood blockbusters, which make all the money, much of it abroad, are being virtually ignored.” Gardels and Medavoy point out that even veteran director Clint Eastwood figured prominently in the nominations by making a Japanese-language film.

Several objections can be made to this. Technically The Queen is foreign, but it’s not foreign-language. Besides, British films have figured in the Oscars since Charles Laughton won as Best Actor by playing a king in The Private Life of Henry VIII back in 1933. Let’s factor out British films, shall we?

Of course Gardels and Medavoy couldn’t know this when they wrote the piece, but none of those “foreign” films won. An American genre film did. A much-respected Hollywood director finally got an Oscar as best director. He remade a Hong Kong film, secure in the knowledge that most Americans won’t watch a foreign-language import like Infernal Affairs.

Plenty of non-foreign films get awards and prestige. There have been years—like 2005—when most of the best-picture nominees were English-language art-house films like Crash and Brokeback Mountain. If The Departed hadn’t been crowned Best Picture this year, one other good contender would have been Little Miss Sunshine. Think back over how many indies have won Best Picture in the last decade or so. The English Patient and Chicago (both Miramax) come to mind. (Gardels and Medavoy never make mention of independent American films, since their argument presumes that non-formulaic films come only from abroad.)

2. Foreign films show “the world in transition as we are living it.” That is, they reflect the real world and hence are more admired and more admirable. In contrast most “American filmmakers too often grind out formulaic, shock and awe blockbusters.”

Again, there are plenty of American films that don’t fall into the “blockbuster” category. Directors like Quentin Tarantino, David Lynch, Tim Burton, the Coen Brothers, and Christopher Nolan are admired internationally for their unconventional films. Conversely, most films made in foreign countries are no less formulaic than ours. Other countries’ popular comedies, crime films, and horror pics are almost never imported into the USA.

3. Hollywood’s blockbusters “may be winning the battle of Monday morning grosses, but are losing the war for hearts and minds.”

Whose hearts and minds are the authors talking about? Doesn’t a film win hearts and minds by drawing people into theaters? So if blockbusters are popular, aren’t they, at least in some sense, winning hearts and minds? Obtaining Oscar nominations means these films have won the Academy members’ hearts and minds, or in the case of the many critics’ awards, the hearts and minds of journalists.

4. “Audience trends for American blockbusters are beginning to show a decline as well, both at home and abroad.” According to Gardels and Medavoy, the fact that films now gross more abroad than at home suggests that the American public is tired of these big pictures.

This claim is self-contradictory. If blockbusters make more in foreign countries than in the USA, then there would not appear to be evidence for a decline of audiences for such film abroad—unless, of course, there has been an overall decline in box-office income worldwide. That’s not true. In the past four years, two films, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King and Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, have made over a billion dollars each internationally. They now stand at, respectively, second and third on the all-time box-office chart (in unadjusted dollars).

Even if we assume that just Americans are getting tired of their own formulaic films, the authors’ argument doesn’t work. They lump Titanic, Jurassic Park, and Star Wars Episode I—The Phantom Menace together with Mission Impossible III and Poseidon as having earned large percentages of their worldwide box-office income outside the USA. Clearly, though, the cases are not comparable. The first three were enormously successful in the USA as well as abroad. Similarly, The Lord of the Rings and the Harry Potter series have brought in around two-thirds of their income outside the US, but one would hardly claim that Americans didn’t like them. The Da Vinci Code brought in over 71% of its total gross abroad but in 2006 it was also the fifth highest-grossing film in the American market.

The authors have chosen two films, Mission: Impossible III and Poseidon, to support their case. Yet in general big action films that perform poorly or even flop in the American market tend to do better in foreign countries, especially if they have auteur directors and big stars. Other examples of recent years have been Oliver Stone’s Alexander and Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven. Indeed, the importance of stars in selling Hollywood films can hardly be overemphasized. For instance, Tom Cruise is enormously popular in Japan, where Mission: Impossible III grossed $44 million of its $398 million worldwide income. There are few comparable international stars working in foreign-language films.

The rising proportion of receipts abroad results largely from reasons other than any putative decline in the popularity of American cinema. For one thing, rising prosperity in developing countries has made movie-going more affordable, and hence there are more movie-goers. The fall of Communism and the new profit orientation in China have opened large new markets for American films. Most crucially, a huge boom in the construction of multiplexes in South America, Europe, and much of Asia during the 1990s and early 2000s raised the number and cost of tickets sold outside the US. It isn’t the American market that has shrunk. It’s the foreign market that has expanded.

Moreover, comparisons between the total box-office income of films within the American market and in foreign ones are often misleading due to currency fluctuations. The recent weakness of the American dollar against many other currencies has made it considerably easier for those in other countries to see Hollywood’s products. Theatrical income does not necessarily reflect the number of tickets sold or the price of those tickets in local currencies. Hence raw statistics may not accurately indicate the actual popularity of any given title.

5. Countries increasingly are favoring their domestically produced films. “Even long-time American cultural colonies like Japan and Germany are beginning to turn to the home screen.”

This isn’t a new and consistent trend. Some countries have been doing quite well in their own markets for years, partly due to government subsidies for the film industry. France is one such market. Germany had a good year in 2006, but 2005 was a bad one. Many such successes are cyclical. Recently films made in Denmark and South Korea have gained remarkable portions of their domestic film markets, and if they decline, other countries will take their places for a period of relative prosperity.

We should also keep in mind that some countries have exhibition quotas for domestic films. South Korea, which provides government subsidies for filmmaking, in recent years has also required that 40% of exhibition days be given over to domestic films. That quota was halved to 20% last July 1, with filmmakers fearing a surge in competition from Hollywood. In fact September saw the Korean share of the domestic market rise to 83%, but this was largely due to two big hits: The Host and Tazza: The High Rollers. Such success can be ephemeral, however, and the government has recently imposed a tax on movie tickets designed to generate a fund for supporting local filmmaking. Variety’s Asian branch has recently predicted a slump in South Korea for 2007.

Moreover, German or Danish films doing well in their own markets doesn’t mean that they’re beating Hollywood at its own game. American films are truly international products, and blockbusters play in most foreign markets. A non-English-language market like Denmark may produce films that gain considerable screen time at home, but they do not circulate outside the country on nearly the scale of the American product.

Take, for example, the most successful German filmmaker of recent years, actor-director Michael “Bully” Herbig (on the left in the frame above). Within Germany his wildly popular comedy Der Schuh des Manitu (2001) sold almost as many tickets as Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, and his over-the-top gay Star Trek parody (T)Raumschiff Surprise—Period 1 (2004) grossed more than twice as much as Spider-Man 2. Most people outside of Germany have never heard of him or his films. There are comic stars like him in many countries. In general popular local comedies—many of them as formulaic as any Hollywood product—don’t travel well.

[Added March 9:

More evidence for my claims that successful foreign-language films often don’t circulate widely outside their countries of origin comes in the February 23 issue of Screen International. In an essay entitled “Calling on the Neighbours,” Michael Gubbins discusses new funding that the European Union is putting into film specifically to promote the wider distribution of films. “The performance of European films outside their home markets remains one of the thorniest issues for the EU’s policy-makers,” Gubbins writes. “Last year’s box-office recovery in many European territories was largely built on the success of local films in local markets and a number of Hollywood blockbusters.”

In 1995, production within Europe totaled 600 films, and it rose to 800 films in 2005. Yet “that rise in production has not been matched by admissions, which have fluctuated strongly over the late five years. There has been little to suggest that increased production has helped European films travel beyond their borders.”]

6. The competition from increasingly successful national cinemas “suggests that we may be seeing the beginning of the end of the century-long honeymoon of Hollywood, at least in its American incarnation, with the world.”

I don’t know what the authors mean by “Hollywood, at least in its American incarnation.” Has Hollywood existed elsewhere?

Actually, I think that Hollywood may well be in decline, at least as a center for filmmaking in the sense of planning, shooting, and post-producing a movie. That isn’t happening, however, for the reasons that Gardels and Medavoy offer in their article.

One factor is the globalization of film financing. Many films these days are co-productions between companies in different countries. It’s sometimes hard to determine the nationality of a film, given its several participants. The English language, however, remains central to most internationally successful films, and that is unlikely to change any time soon. The most popular stars still tend to come from English-speaking countries or to be able to speak English well, as actors like Juliette Binoche and Penélope Cruz can.

Another factor in globalization is the increasing tendency to make American-based productions partly or entirely abroad. Off-shore production has actually been fairly common since World War II. In the post-war austerity, many countries restricted how much currency could be taken out, and Hollywood firms spent their income by covering the production costs of films made abroad.

Even with the easing of such restrictions, the trend continued. The most traditional modern reason is simply cost-cutting through inexpensive labor and other expenses—advantages that have long been found in Eastern European countries. More recently countries have seen the economic advantages of an environmentally friendly enterprise like filmmaking. More and more of them have put various tax and other financial benefits into place in an effort to be competitive in the search for off-shore productions. For example, the February 2-8, 2007 issue of Screen International contains an ad placed by the Puerto Rico Film Commission (p. 40) declaring that “Puerto Rico is Ready for Action” and offering a remarkable 40% rebate on local expenditures. It also touts the country’s “experienced bilingual local crews” and its “infrastructure.”

One important cause for the off-shore trend that I deal with in The Frodo Franchise is the fact that technological change now offers the possibility of making films entirely abroad, from planning to post-production. Ten years ago it would have been almost unthinkable to have sophisticated special effects created by anyone other than the big American specialty firms like Rhythm and Hues or Industrial Light & Magic. Now world-class digital effects houses are springing up around the globe, and one of the top firms, Weta Digital, is located in a small suburb of Wellington, New Zealand. When a huge, complex production like The Lord of the Rings can be almost entirely made in a country with a miniscule production history, there is far less reason for American producers to confine any phase of their projects to the traditional capital of filmmaking.

There may indeed be an ongoing decline in Hollywood’s importance in world cinema, but it isn’t happening quickly. For one thing, there is no reason to think that US firms will soon cease to be the main sources of financing and organization of filmmaking. Even if Hollywood stopped making films and just distributed the most popular ones from abroad and from American indies, it would remain the most important locale for the film industry. As anyone who studies or works in that industry knows, distribution is the financial core of the whole process.

Finally, we shouldn’t forget that since early in the history of the cinema the USA has been far and away the largest exhibition market for films. No other single country can match it, and Europe’s attempts to create a united multi-national market to rival it have so far made slow progress. With such a firm basis, the Hollywood industry can simply afford to spend more on its films than can firms in most countries. Expensive production values help create movies that have international appeal, in part precisely because they are blockbusters of a type that are rarely made anywhere else.

In the international cinema, “shock and awe” and “hearts and minds” aren’t always as far apart as we might think.

Gardels and Medavoy’s analysis of Hollywood vs. foreign films falls into a common pattern within journalistic writing on entertainment. As soon as some trend or apparent trend is spotted, the commentator turns to the content of the films to explain the change. If foreign or indie films dominate the awards season, it must be because blockbusters have finally outworn their welcome. If foreign or indie films decline, it must be because audiences want to retreat from reality into fantasy. It’s an easy way to generate copy that sounds like it’s saying something and will be easily comprehensible to the general reader.

Such explanations depend on considerable generalizations that are usually made without taking into account the context of industry circumstances. Fluctuations like currency rates, tax loopholes, genre cycles, quotas, labor-union agreements, and similar factors interact in complex ways. All these are really difficult to keep track of and analyze, and most writers don’t bother, even though that would seem to be part of their job.

Almost inevitably commentators also fail to note that films typically take a very long time to get from conception to screen. Most releases of today actually reflect trends that were happening a few years ago. The world film industry is just too cumbersome to turn on a dime, or even on a few billion dollars.

Bs in their bonnets: A three-day conversation well worth the reading

From DB:

The Film faculty and graduate students at the University of Wisconsin—Madison are a close-knit bunch. Keeping in touch via email, we exchange ideas about teaching and research, as well as passing along gossip and peculiar things that appear on the Internets. Our community includes grad students and alumni from several generations. The youngest are taking courses now; the most senior were here in the early 1970s, and they still have all their marbles.

Over three days earlier this month, there was a lightning round of exchanges on B films. With the permission of the participants, I’m posting highlights of the correspondence here because it exemplifies one way in which the Web can advance film studies.

Most film writing on the web comments on current films or video releases. Nothing wrong with that. But if you’re a researcher into film, you also want to talk about history. It’s rare to find an online debate about historical evidence and alternative interpretations of that evidence.

So to scratch my academic itch, I give you mildly edited extracts from our UW cyber-dialogue. You’ll see some hard-working professors practicing imaginative pedagogy, and you’ll find ideas for research and teaching. You’ll also see, I hope, that film studies can make progress by asking precise questions and refining them through inquiry and critical discussion.

Note to film scholars: Blogs are seldom cited in academic writing, but if you intend to use this material in your own research, it would be courteous to mention these esteemed sources, as they mention others.

To be a B, or not to be a B

First, a little background. Today sometimes we call low-budget films or just poor quality movies “B movies.” But across the history of Hollywood the term had a more specific meaning. You can find a primer at GreenCine, but here’s a little more industrial context.

During the heyday of the studio system, most theatres ran double bills—two movies for a single ticket (along with trailers, news shorts, cartoons, and the like). Very often the main feature, or A picture, was a high-budget item with major stars from a significant studio. The B film was low-budget, ran to only 60-80 minutes, and showcased lesser-known players. A B tended to be distributed for a flat fee rather than a percentage of the box office.

(I’ve just distinguished Bs in terms of its level of production; as you’ll see from the dialogue, we can think of them in other ways too.)

MGM, Warner Bros., Twentieth Century-Fox, and other major companies made B pictures as well as As. Often the B film was part of a series. Fox had Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan, MGM had Andy Hardy and Dr. Kildare. Since the most powerful studios owned theatres as well, the B film filled out the double bill with company product. Moreover, the Bs allowed studios to make maximum use of the physical plant. Sets built for an A picture could be used for a B, and actors idling between big projects could take small parts in Bs. Bs could also serve as training ground for stars, crews, and directors who might move up.

Other companies concentrated wholly on making B pictures. The most famous of these so-called Poverty Row studios are Monogram, Republic, Mascot, and Producers Releasing Corp. Besides turning out stand-alone Bs, the Poverty Row studios specialized in serials, like Don Winslow of the Navy and Hurricane Express (1932, Mascot, with John Wayne, right).

Other companies concentrated wholly on making B pictures. The most famous of these so-called Poverty Row studios are Monogram, Republic, Mascot, and Producers Releasing Corp. Besides turning out stand-alone Bs, the Poverty Row studios specialized in serials, like Don Winslow of the Navy and Hurricane Express (1932, Mascot, with John Wayne, right).

Still other studios, the so-called Little Three, hovered between A and B status. Universal, Columbia, and RKO were smaller companies, and some of their A pictures might have been considered really B’s, in terms of budget and resources. This is one theme of the conversation that follows.

As the major studios cut back production after the war, many B pictures were made as independent productions. Double bills in the US persisted into the 1960s, and Roger Corman and other producers turned out B-films for drive-ins, declining picture palaces, and rural theatres. Still, the prime years of B films were the 1930s-early 1950s. They have always been an object of admiration for cultists; recall that Godard dedicated Breathless to Monogram. Important directors like Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher started in B production. Several Bs, notably noirs and horror films, are staples of cable and home video.

Want to know more? Here’s some essential reading: Tino Balio’s The American Film Industry, rev. ed. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985); Douglas Gomery, The Hollywood Studio System: A History (London: British Film Institute, 2005); Todd McCarthy and Charles Flynn, eds., Kings of the Bs: Working within the Hollywood System (New York: Dutton, 1975).

Now to the question of the day.

Day 1: What do I teach?

It all began on 6 February. (Cue harp music and dissolve here.) Paul Ramaeker of the University of Otago asked an innocent question….

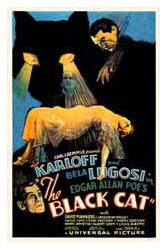

OK, so I am running a grad seminar (or, more precisely, our closest equivalent- a 4th year Honours course) on Classical Hollywood Cinema. I want to spend time on the industry, obviously, which raises questions about what to screen for those weeks. I thought an A pic and a B pic. For the A, I was thinking about Robin Hood. For the B, I’m not sure, but I had for other purposes been considering a double bill of The Black Cat and I Walked with a Zombie. Now, the latter, I know, is a B pic; but is The Black Cat a B? It’s about an hour, which suggests a B and it’s not got a lot of sets. But it’s got Lugosi and Karloff, who surely were two of Universal’s bigger stars at the time, right? So which is it?

Any other good B pic recommendations are welcome.

The replies came fast. First, from Jane Greene of Denison University:

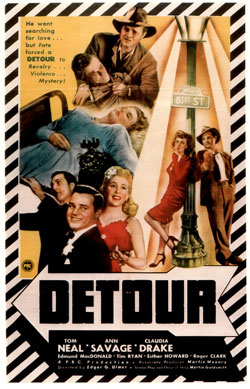

I do the same thing in my history class and I’ve found that Casablanca and Detour work well. It helps that most students have heard of Casablanca and a surprising number have seen it. You can point out how this “timeless classic” was very much a product of collaboration, how the star system, budget and schedule determined the look of many scenes, and it also allows you to discuss censorship… I mean self-regulation. (See Richard Maltby’s “Dick and Jane Go to 3.5 Seconds of the Classical Hollywood Cinema” in a little-known book called Post-Theory.)

Aljean Harmetz’s The Making of Casablanca is coffee-table-y, but she did consult tons of production and publicity material and there are reproductions of production documents (script pages, even a Daily Production Report!).

And, if yer willing to go Poverty Row for yer B Film, Detour just rocks. It’s so obviously re-using 2-3 sets and locations, has the foggiest scene ever shot, and long voiceovers that sound deep and poetic and take up half the film. The kids love it. And it could ease you gently into the waters of film noir, should you wish to go that way (and I bet you do).

And, if yer willing to go Poverty Row for yer B Film, Detour just rocks. It’s so obviously re-using 2-3 sets and locations, has the foggiest scene ever shot, and long voiceovers that sound deep and poetic and take up half the film. The kids love it. And it could ease you gently into the waters of film noir, should you wish to go that way (and I bet you do).

Leslie Midkiff DeBauche of UW—Stevens Point also shared a teaching technique.

I teach the 1930s with a colleague in the History Department and we like to create a whole program: News Parade of 1934 from Hearst Metronome News; Three Little Pigs (1933), followed by the first half of a documentary called “Encore on Woodward” about the Fox Theater opening in Detroit. It opens in 1929 and is wonderful–it has clips of late silents like Seventh Heaven, sound comes, and we end it after a woman remembers how her boyfriend proposed to her, in the balcony, during Robin Hood. We usually show the 1936 (I think, it could be 1934) year-in-review newsreel that is on the Treasures of the Archive

I set of DVDs and the feature we use is It Happened One Night. What the students like best though is the popcorn and the give-a-ways between the parts of the program: Nancy Drew and Superman, a bag of groceries with food items from 1930s–turns out to be current student food–Bisquick, Snickers, Jiffy peanut butter,Ritz crackers. The grand prize bank night equivalent is an A on the final exam. They freak! It is like they won big money.

From Notre Dame comes Chris Sieving on RKO:

In researching Lewton last year I found a few sources that argue vehemently that the Lewton-Tourneur-Wise-Robson horror films were not B films, but more like nervous As: budgets were decent, prestige factor was high, occasional name stars (like Karloff).

Another veddy interesting and perhaps more “authentic” B film, besides Detour, is Stranger on the Third Floor (1940). It contains some very bizarre and magical Peter Lorre acting, plus some people call it the “first” film noir. (Speaking of film history myths that need debunking…)

Lea Jacobs, doyenne of Film Studies here in Madison interjects:

I would think The Black Cat is a B, not only because of running time but because of genre. When I was researching the distribution of B’s at RKO I was surprised by the way the horror films made by Val Lewton’s unit at RKO (many justly celebrated today) were treated as the lowest of the low–opening alongside films with titles like Boy Slaves at the small Rivoli or Rialto theaters in New York for very short runs, and later booked in and out of theaters nationally on an ad hoc basis. See my article, “The B Film and the Problem of Cultural Distinction,” Screen 33, no. 1 (Spring 1992): 1-13. I also think that Universal simply wasn’t making many A films in 1934, even with their recognizable stars.

I would think The Black Cat is a B, not only because of running time but because of genre. When I was researching the distribution of B’s at RKO I was surprised by the way the horror films made by Val Lewton’s unit at RKO (many justly celebrated today) were treated as the lowest of the low–opening alongside films with titles like Boy Slaves at the small Rivoli or Rialto theaters in New York for very short runs, and later booked in and out of theaters nationally on an ad hoc basis. See my article, “The B Film and the Problem of Cultural Distinction,” Screen 33, no. 1 (Spring 1992): 1-13. I also think that Universal simply wasn’t making many A films in 1934, even with their recognizable stars.

When I teach the B film I like to show Detour and Moon Over Harlem (now out on DVD). The latter has two really amazing scenes in a movie made for less than $10,000. But maybe that is too Ulmer heavy. Anyway you can’t go wrong with I Walked with a Zombie.

Kevin Heffernan of Southern Methodist University weighs in.

Great movies, Paul! “Cries of pleasure will be torn from” your students (as they were from our hero in S/Z).

Great movies, Paul! “Cries of pleasure will be torn from” your students (as they were from our hero in S/Z).

The Black Cat is an A picture, I think. All of the Universal horror movies ran between 65-71 mins, so this is just under their average. Also, names above the title usually point to an A, and I’m virtually certain the movie would have played a percentage (rather than a flat fee) in its initial engagement. I would imagine that a Universal horror picture sold well in subsequent run as a component in double bills, so they would be sort of de facto B pics in some situations.

And it is worth mentioning to your students, as Elder Goodman [Douglas] Gomery pointed out years ago, that the Deanna Durbin musicals were much more financially successful for Laemmle et cie than the horror movies. They’re all out on video now. Ghastly, unwatchable, wretched.

Lea Jacobs replies:

Universal is one of the little three in 1934, and, unlike today, when horror films command high budgets and garner big returns, in the 1930s horror films and sci fi were the stuff of serials and the bottom half of the double bill. I would have to see a contract before I believe it played for a percentage. One way, apart from that, to decide, is to look at where it opened in New York, how long it played and where it played subsequently in the key cities.

Doug Gomery, Resident Scholar at the University of Maryland, is succinct on I Walked with a Zombie:

RKO in the 1940s was a low budget studio and Floyd Odlum owned it. Odlum went cheap after his experiment with the likes of Citizen Kane. So it was B pure and simple.

Then Hughes bought it after the war and dabbled with his strange way of doing things.

It’s now 5:30 on the same day, but are our eager scholars tired? You have to ask?

Lea Jacobs follows up:

It is pretty safe to assume that most Universals in the 1930s were in the B range–their films were shown on the bottom of the double bills in theaters owned by the Majors. Even in the 1920s one reads Variety complaining about the cheapness of Universal’s product. A far cry from when it was taken over by Doug’s favorite Lew Wasserman.

Jim Udden of Gettysburg College jumps in, invoking the founder of film-industry studies at UW, Tino Balio:

Tino does discuss this issue in Grand Design. According to him, Frankenstein and Dracula are clearly A pics, part of Universal’s strategy to break into the first-run market, since, as we all know, they had very few theaters of their own. But Black Cat is only one third the budget of Frankenstein, according to the figures in IMDB.com. Does that make it a B pic? Perhaps. Yet it seems to me that this film could still have been marketed and released like the initial Universal Horror films, riding on their coat tails, so to speak, but with less actual money invested in the production.

Tino does discuss this issue in Grand Design. According to him, Frankenstein and Dracula are clearly A pics, part of Universal’s strategy to break into the first-run market, since, as we all know, they had very few theaters of their own. But Black Cat is only one third the budget of Frankenstein, according to the figures in IMDB.com. Does that make it a B pic? Perhaps. Yet it seems to me that this film could still have been marketed and released like the initial Universal Horror films, riding on their coat tails, so to speak, but with less actual money invested in the production.

So was Black Cat more often one of these “featured” features, or was it usually the bottom half of the double bill, as Lea says? Maybe this is an AB pic?

This to me, sound like a researchable topic! (I myself have not time for this, unfortunately…)

Lea Jacobs replies:

Yes, Jim, I agree, a researchable question that I don’t have time for either. But a distinction that can be made, without research (or prior to it) is one between A/B at the level of production planning and budget and A/B at the level of distribution. Sometimes relatively “cheap” films were marketed as As (Variety usually complains about this its reviews!). Thus, to be really certain of how a film lines up, you have to look at both the budget ranges at the studio at the time of the films’ production, and the distribution pattern, including, of course, whether it was distributed for a percentage or flat fee.

Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University, comes rolling in at 10:30 pm.

* The trouble with some of the great B’s, like The Black Cat, Detour, and I Walked with a Zombie is that they’re so good that they don’t give a sense of the real purpose of the “B,” which was to hold down half of a double bill, and amortize overhead at the studios over a larger number of opportunities for revenue – that is, individual films. A comparison of scenes from an A film and a B film using the same standing sets does this nicely; I use the RKO New York street set, visible in Citizen Kane and Stranger on the Third Floor, as an example. (A great visual example I’d like to make would be Lewton’s Ghost Ship, which is said to be a script written for an existing ocean liner set, but I haven’t seen that set in another RKO film as yet.)

*I’ve often done a clip show that involves:

A. Clips from films like the Lewtons, or the Schary-Rapf films at MGM (like Pilot #5 and Joe Smith, American), or one of the series films, like a Maisie film. These films show that the resources of a big studio, such as talent, standing sets, skilled cinematography and editing departments, etc, could generate a film that, while it might have been double feature fodder, still maintains a sense of `quality’ that, perhaps, studios wanted to maintain for purposes of brand equity.

B. Clips from fairly awful B’s, like the Dick Tracys or Tim Holt Westerns at RKO, which show what could happen when questions of production value were not attended to quite so scrupulously, simply because, given the films’ titles, they were likely to draw from a market which did not make attendance decisions in the same way as patrons of, say, Pilot #5.

C. Clips from minor studio “B” westerns, ala Buck Jones. REALLY gets the point across about the relationship between production expenses and expected grosses; clearly, these films were made on a precise calculus. As films, of course, they’re nowhere near as interesting as the Lewtons or RKO “B’ noirs like The Devil Thumbs a Ride, but they work, particularly when students can’t really tell the difference between a Buck Jones, a Tom Mix, or a Three Mesquiteers – that’s sort of the point. Peter Stanfield’s work on “B” Westerns, however, shows how the signifying practices of the B Westerns, production values aside, could be truly divergent from anything in the A film canon, and worth studying. But in defense of my students, being trapped in a screening room with a true B Western at full length can be a grueling experience.

*A handout listing the films produced in a single given year by one studio, grouped by genre, and with A or B indicated in each case. 1939 is a good year to do this with, as it contains some of the few studio films students have even ever heard of. They can see how certain studios specialized in certain genres, and how B’s supported A’s in the production calendar.

*Finally, by way of an outro, of course, talking about modern equivalents of B films, and even arguing whether such equivalents exist in the film or cable marketplaces. (Jim Naremore’s chapter on direct to video “erotic thrillers” in his wonderful book on noir, More than Night, can be very helpful here.)

Our researchers retire from the field. But not for too long.

Day 2: Diving for Dollars

Brad Schauer, Ph.D. candidate at UW-Madison fires this off at 9:33 CST on 7 February:

Wow, what a digest I received this morning! With all this B movie talk, I couldn’t resist adding my $.02.

The Black Cat is a tricky case – it was worth flipping through some of the secondary sources to investigate (Senn 1996; Weaver, Brunas, and Brunas 1990, Soister 1999). In a sense, it’s a clear B. The budget was about $90K and was scheduled for a two-week shoot. Compare this to next year’s Bride of Frankenstein, which cost $400K and took Whale about six weeks to film. Plus, Black Cat has all the wonderful hallmarks of a quintessential B: lurid storyline, short running time, sometimes incomprehensible narrative (due in this instance to censorship), etc.

And it was devalued by the critics because of its genre and the concomitant transgressive material (the flaying scene is still shocking).

However, the film was also a big hit for Universal, its top moneymaker for 1934. Looks like it brought in rentals around $250K – which isn’t a lot, but it suggests a percentage release, at least in its initial run. Variety also said it had “box office attraction” because of the current popularity of Lugosi & Karloff, teamed for the first time. Someone would have to investigate its distribution patterns to be sure, but it kinda looks like a B picture that was sold as an A, as Lea suggested. Maybe Universal knew it could throw a cheap movie out there and it would succeed based on the popularity of the genre and the stars. It’s a kind of precursor to all those low-budget, highly-profitable horror films like Halloween and Saw. So for me it’s about 4/5th B, 1/5th A.

Would I show it as an example of a B? As Kevin Hagopian mentioned, it’s really much too good to be a truly representative example, but students will probably like it more than a Dr. Kildare movie or something. If you really want to sock it to them, dig into the Sam Katzman filmography. Try one of the Jungle Jims or the Lugosi Poverty Rows.

David already mentioned the real gems of the studio Bs, the Motos. The Chans are great too. (I can even watch the Monogram Chans, although the Karloff Mr. Wongs can be a real slog.) As far as other mystery series go, the Universal Holmes films are extremely well done, the Dick Tracys, Perry Masons, and Torchy Blaines are a lot of fun, and I have a soft spot for the Falcon films due to AMC early morning reruns in my childhood. The Kitty O’Day mysteries are on my “to watch” pile, but I’m not optimistic. Follow Me Quietly (1949) also comes to mind as a great B-noir.

And also, the Thin Man movies weren’t really Bs. Not responding to anyone – just needed to get that out there. Closer to Bs would be MGM’s Sloan mystery knockoffs, which are fun too (especially Fast and Furious, which is fortunate enough to have Rosalind Russell).

Whew, thanks for reading if you made it this far.

As a new day dawns on Texas, Kevin Heffernan has more thoughts.

Thanks for the info, Brad. Yes, Black Cat is a curious hybrid case. For a “truer” example of a Karloff/Lugosi B from Universal, see The Raven from the following year–most notably in its use of fairly minimal, obviously left-over sets (nothing like the very bold production design of Black Cat). And, although I recall that Kristin is a Lew Landers fan (didn’t she call him “lightly likeable at least” in Breaking the Glass Armor?), his name was somewhat synonymous with quotidian program pictures in the 30s and 40s.

Thanks for the info, Brad. Yes, Black Cat is a curious hybrid case. For a “truer” example of a Karloff/Lugosi B from Universal, see The Raven from the following year–most notably in its use of fairly minimal, obviously left-over sets (nothing like the very bold production design of Black Cat). And, although I recall that Kristin is a Lew Landers fan (didn’t she call him “lightly likeable at least” in Breaking the Glass Armor?), his name was somewhat synonymous with quotidian program pictures in the 30s and 40s.

My assertion that Black Cat was an A referred to my understanding of the terms of its first-run distribution . But I actually had little evidence, I have discovered, as I looked over my notes on the movie from Tino’s seminar a few years back.

Lea and Doug’s observations about Universal’s “Little Three” status and the general role its horror pictures played in the larger patterns of distribution seem spot on to me and of course became more prevalent (inflexible, even) in the post-Laemmle years. The only exception to this that I can think of was Son of Frankenstein, which was U’s entry in the superproduction cycle of 1938-39 (stars on loan from other studios, spectacular production design, initial plans to shoot in Technicolor, etc), but that movie was really the last gasp of the A horror pic at the studio, I think.

And at 10:10 AM CST Lea Jacobs is back at the keyboard.

I guess Brad has the last word on The Black Cat. Nothing like doing the research.

Now about the Thin Man series. In the essay on film budgets at MGM that appeared a few years back, I recall that these films were in the “B” range for MGM (about $250,000). (See H. Mark Glancy, “MGM Film Grosses—1934-1948: The Eddie Mannix Ledger,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 12, 2, 1992: 127-144.) This is a lot of money relative to what other studios were spending on B films, of course, but all of MGM budget ranges were high relative to the other majors (the average MGM A was between $700,000 and $1 mil as I recall). So I agree that the Thin Man films are elegant and well dressed and don’t fit anyone’s conception of a B, but at least when considered from the perspective of film budget categories at MGM, wouldn’t these count as Bs? Or, put another way, what would you count as an MGM B?

Now about the Thin Man series. In the essay on film budgets at MGM that appeared a few years back, I recall that these films were in the “B” range for MGM (about $250,000). (See H. Mark Glancy, “MGM Film Grosses—1934-1948: The Eddie Mannix Ledger,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 12, 2, 1992: 127-144.) This is a lot of money relative to what other studios were spending on B films, of course, but all of MGM budget ranges were high relative to the other majors (the average MGM A was between $700,000 and $1 mil as I recall). So I agree that the Thin Man films are elegant and well dressed and don’t fit anyone’s conception of a B, but at least when considered from the perspective of film budget categories at MGM, wouldn’t these count as Bs? Or, put another way, what would you count as an MGM B?

Doug Gomery adds in re MGM B-pictures:

Nicholas Schenck was no great man, but he ran Loew’s/MGM from 1927 to 1954. To him the Thin Man series were Bs from his studio. Remember block booking? These simply made MGM a more attractive package. The question of A v. B is at its heart a budget decision and then a release one. The New York-based men, like Schenck, made those decisions.

Day 3: B Mania Subsides; some answers, more questions

8 February: Brad Schauer revisits Nick and Nora:

Real quick about the Thin Mans before I run to lecture: I know I was being a bit contentious when I said they weren’t Bs. Lea and Prof. Gomery are absolutely right that if you go by budget, they’re Bs…at least initially. But by the time we get to Another Thin Man (1939), the budget is up to $1.1 mil, only a couple of Gs less than Ninotchka. 1944’s Thin Man Goes Home is budgeted at $1.4 mil, only about $500K less than Meet Me in St. Louis (!).

Real quick about the Thin Mans before I run to lecture: I know I was being a bit contentious when I said they weren’t Bs. Lea and Prof. Gomery are absolutely right that if you go by budget, they’re Bs…at least initially. But by the time we get to Another Thin Man (1939), the budget is up to $1.1 mil, only a couple of Gs less than Ninotchka. 1944’s Thin Man Goes Home is budgeted at $1.4 mil, only about $500K less than Meet Me in St. Louis (!).

Another reason they don’t seem like Bs to me is that they were consistently among the top grossers for MGM in the ’30s. But so were the Andy Hardys, you might argue, and they’re clearly Bs.

Except…from what I could tell from analyzing the distribution patterns of the ’35-’36 season (not done this morning, don’t worry), After the Thin Man played in major first run theaters, and hardly ever with a second feature until it hit the nabes (neighborhood theatres). It was distributed like a big deal A, and you can sense the exhibs’ excitement in the trade press that another Thin Man installment was coming out.

Finally, we can look at the running times. MGM’s Bs were sometimes longer than other studios, but the first sequel After the Thin Man is nearly two hours long. Compare that to MGM’s Sloan mysteries (Thin Man knock-offs), which clock in at 75 minutes each.

So, like The Black Cat, the Thin Man films seem an unusual case. The first installments may have been budgeted as Bs, but as the series caught on, it was treated like an A property, both in terms of production and distribution – compared to the Andy Hardy films, for instance, whose budgets remained quite low for the entire series.

Although I think the Hardy films were often exhibited as the top of a double feature, but that’s another story.

I kinda feel like lecturing on this stuff this morning instead of the continuity system, although I’m not sure the students will want to hear about distribution patterns at 8:30 a.m.

Lea Jacobs’ fingers fly over the keyboard a few moments later:

Lea Jacobs’ fingers fly over the keyboard a few moments later:

This is very interesting, Brad. I wonder if any of this could be correlated with William Powell and Myrna Loy’s salaries? That is, maybe the series made them stars (I am pretty certain that they were not prior to the first of the series). Higher budgets for later Thin Man films might have been a function, not only of more expensive settings and shooting practices, but also of MGM raising the stars’ pay.

Anyway, it might be worth looking at the publicity attached to the two stars over the course of the series and see if it increased and if it changed. I don’t know of any source that would tell you what they were paid (at least any source that can be trusted) although contracts might exist at AMPAS.

And then, of course, there is the question of whether or not the cutting rate went down over the course of the series…

This last remark refers to an email entry of my own, sent about the same time:

I have another idea about how to spot a B. It isn’t infallible, but it might serve as an index. I’m thinking Average Shot Length.

Oho, you think, here we go again. But hear me out.

Last night I watched THE DEVIL THUMBS A RIDE, a 62-minute RKO item from 1952, directed by Felix Feist. Laurence Tierney is the most recognizable name in it, and if you know him only from RESERVOIR DOGS, you might not recognize him. Good suspense, very few sets (lots of car driving with background process plates), familiar character actors wandering in to do a bit part (including Harry Shannon, aka Charles Foster Kane’s father). A surprisingly violent twist at one point. Even the title tells you you’re watching a B.

Last night I watched THE DEVIL THUMBS A RIDE, a 62-minute RKO item from 1952, directed by Felix Feist. Laurence Tierney is the most recognizable name in it, and if you know him only from RESERVOIR DOGS, you might not recognize him. Good suspense, very few sets (lots of car driving with background process plates), familiar character actors wandering in to do a bit part (including Harry Shannon, aka Charles Foster Kane’s father). A surprisingly violent twist at one point. Even the title tells you you’re watching a B.

And 6.0 second ASL.

We found in our Hollywood book [The Classical Hollywood Cinema], and pretty reliably since, that during the 1930s-1950s the Hwood norms ranged from 8-11 seconds per shot. But those samples were drawn, I increasingly realize, from mostly A pix, because in the vast initial filmography we compiled, what we found in archives tended to be A pix. Only William K. Everson had a substantial collection of B titles on our first list, more even than the Library of Congress.

So maybe Bs tend to be cut faster? Here are some other ASLs from the 1930s, from B or B+ items: Murder by an Aristocrat, 6.3 seconds; Nancy Drew and the Hidden Staircase, 6.8; Indianapolis Speedway, 5 seconds; Tarzan the Ape Man, 6.6 seconds; Tarzan Finds a Son, 3.6 seconds!

From the 1940s: Parole Fixer, 6.6 seconds; Chain Lightning, 6.3; Framed, 6.3.

Now this mini-sample has skewing problems of its own–lots of mystery and action pictures. We’d need to test it with other genres. Can there be fast-cut musicals? (Actually, yes; Footlight Parade.) Comedies? (Yeah, Duck Soup.) Melodramas? (Yep, Mr. Skeffington.) Still, I don’t have enough from any genres to say much of substance. As for our two big horror examples, The Black Cat falls in the A-picture range (8.5 seconds), while The Raven is much faster cut (5.7 seconds).

And what about the real Bs–the Westerns from Monogram et al? Plenty of them play on TCM and we have tons sitting in the Wisconsin Center for Theater Research, but I confess to having watched only a handful and never counted shots. Also, films with lots of stock footage (travel, racetracks, jungle animals, etc.) tend to be cut faster…and we know that Bs use lots of stock footage.

Interestingly, of major directors I’ve sampled, Hitchcock’s ASLs come closest to the ‘B’ touch. Selznick famously told Hitchcock to slow down the pace because his British films were too “cutty”; was there an unspoken belief that fast cutting was a little downmarket if you were making A pictures? Hitchcock sometimes cut fairly fast (until Rope and Under Capricorn, of course): 6.4 seconds for Lifeboat (on right), 7.3 for The Paradine Case, 6.8 for Notorious.

Interestingly, of major directors I’ve sampled, Hitchcock’s ASLs come closest to the ‘B’ touch. Selznick famously told Hitchcock to slow down the pace because his British films were too “cutty”; was there an unspoken belief that fast cutting was a little downmarket if you were making A pictures? Hitchcock sometimes cut fairly fast (until Rope and Under Capricorn, of course): 6.4 seconds for Lifeboat (on right), 7.3 for The Paradine Case, 6.8 for Notorious.

ASL can’t be an infallible detector because there are some Bs with ordinary ASLs, and a few with longish ones. Detour clocks in with an unusually lengthy 14.3 second ASL. Joseph H. Lewis’ The Big Combo (1954), made for Allied Artists (the revamped Monogram), boasts an ASL of 14.6 seconds and has many single-shot sequences (though given its cast and technical credits, it’s arguably a B+). Still, most marathon ASLs seem to come in A pix by Minnelli, Preminger, Wilder, and their peers.

What makes this stuff interesting is a long-standing assumption that because of short shooting schedules, B films couldn’t afford many camera setups. I think there’s an unspoken belief that directors used longer takes to get more footage per day. The shot length averages suggest the opposite: B films can use lots of shots, and a surprising variety of setups.

This may also suggest a difference between A studios making B pictures and Poverty Row studios making only B pictures. Again, my sample is slanted toward the former. Nevertheless, although faster than normal cutting isn’t a necessary condition of a studio-era B picture, it may be a symptom of one. If other indicators point toward a B, and you’ve got an ASL of less than 7 seconds, that could strengthen the case.

Scott Higgins of Wesleyan University raises a new question about my ASLs:

Fascinating. Are shot scales different as well? Might editing compensate for cheaper mise-en-scene? In any case, this is good evidence that staging takes time!

Coming full circle

On 8 February, at 8:00 CST, Paul Ramaeker, who started it all two days earlier, writes:

Wow! Thanks to everyone for their input on this; now I just have to sort through everyone’s arguments and make a judgment call (given the degree of controversy over the question). I have to say, though I have now been convinced to use Detour as one of my screenings for that week, so as to have an example of Poverty Row, it would seem that either Black Cat or Zombie would work (as well as a Moto, which I hadn’t thought of at first), not least because there is some element of ambiguity in both cases that would be fodder for discussion.

Wow! Thanks to everyone for their input on this; now I just have to sort through everyone’s arguments and make a judgment call (given the degree of controversy over the question). I have to say, though I have now been convinced to use Detour as one of my screenings for that week, so as to have an example of Poverty Row, it would seem that either Black Cat or Zombie would work (as well as a Moto, which I hadn’t thought of at first), not least because there is some element of ambiguity in both cases that would be fodder for discussion.

I have to say, though, I think the reminders about the status of the Little 3, as well as the budgetary info, are kinda persuasive in the case of The Black Cat. And while I’d hate to lose Zombie, I can see some value in screening two films at different production levels by the same director, Ulmer in this case. There may well be such a thing as too much Ulmer, but if anyone could possibly object to a Black Cat/Detour double bill, they’d have to be kicked out of the class.

Cheers to all!

Weekly colloquium meeting of the Film area, UW–Madison

3 notions about CREMASTER 2

DB here:

The week before last brought Matthew Ryle to the UW–Madison campus for a talk and a panel discussion. As Ryle pointed out, it’s hard to decide exactly what he should be called. He has the title of Chief Fabricator at Matthew Barney’s studio, and in Barney’s Cremaster film cycle he serves as Production Designer. He’s been called a Set Designer too, and he assists in the making of sculpture pieces that Barney exhibits in museums. Ryle is an important artifact-maker in his own right, having built the tallest sign in North America.

Nobody could have been more unpretentious than Matt Ryle, in olive sweatshirt and blue jeans, explaining the whys and wherefores of Barney’s enigmatic art. He gave a concise introduction to Cremaster 2, pointing up its reliance on Mailer’s nonfiction novel about Gary Gilmore, The Executioner’s Song. After the film, Ryle talked about the film’s Mormon and Masonic symbolism and the connections that Barney finds among killer Gilmore, Houdini, and the 1893 International Exposition, which Barney relocates from Chicago to Alberta, Canada.

Nobody could have been more unpretentious than Matt Ryle, in olive sweatshirt and blue jeans, explaining the whys and wherefores of Barney’s enigmatic art. He gave a concise introduction to Cremaster 2, pointing up its reliance on Mailer’s nonfiction novel about Gary Gilmore, The Executioner’s Song. After the film, Ryle talked about the film’s Mormon and Masonic symbolism and the connections that Barney finds among killer Gilmore, Houdini, and the 1893 International Exposition, which Barney relocates from Chicago to Alberta, Canada.

Ryle discussed some of Barney’s filming procedures too. Barney shoots plenty of coverage, with many angles to permit inserts and matches on action. He favors delicate and lustrous lighting, both in the exteriors and the interiors, many of which are studio sets. Cremaster 2 cost about $1.7 million, and it looks it. There is ambitious CGI work in the Mormon Tabernacle, and the imagery is often spectacularly beautiful, showing off the landscapes of the Bonneville Salt Flats and Canadian glaciers and enticing props like the glittering mirrored saddle and the shapely furniture that surrounds the players.

The films

For those who haven’t yet heard, Cremaster is a series of five films made between 1994 and 2002. Each one suggests a narrative, but it doesn’t give us a traditional plot. Rich in surreal details, the action presents humans and fantastic creatures, most in fairly static postures or caught in repetitive actions. They exist in vacant spaces, either colossal ones, like a blimp or the Utah landscape, or cramped chambers. Their actions and circumstances work out Barney’s private mythology, which is based on the descent of the testes during the embryo’s development in the womb. (The cremaster is the muscle that controls the contractions of the testes.) As in the paintings of Salvador Dalí (another artist interested in bodily penetration and drippy fluids), the actions we see symbolize public and historical events, but at one remove and filtered through esoteric symbolism.

Cremaster 2, which we saw last week, is one of the most accessible installments, but it’s still very opaque. It begins with imagery of stupendous horizons, some tipped vertically. We’re introduced to several figures who’ll recur: an astonishingly wasp-waisted woman, a young man and woman who seem to be consulting her for advice, Harry Houdini being trussed up for an escape, and a desperate man parked at a gas station. There are also some isolated actions, most memorably a man and woman in coitus, with her pinched waist encased in a plastic girdle. There are bees, honey, saddles, cowpokes, and petroleum jelly. The film interweaves these materials around certain emblematic actions. Crucially, the young man in his Mustang (which is coupled by fabric to another Mustang) shoots the station attendant and eventually is executed by means of a rodeo bull-ride.

Cremaster 2, which we saw last week, is one of the most accessible installments, but it’s still very opaque. It begins with imagery of stupendous horizons, some tipped vertically. We’re introduced to several figures who’ll recur: an astonishingly wasp-waisted woman, a young man and woman who seem to be consulting her for advice, Harry Houdini being trussed up for an escape, and a desperate man parked at a gas station. There are also some isolated actions, most memorably a man and woman in coitus, with her pinched waist encased in a plastic girdle. There are bees, honey, saddles, cowpokes, and petroleum jelly. The film interweaves these materials around certain emblematic actions. Crucially, the young man in his Mustang (which is coupled by fabric to another Mustang) shoots the station attendant and eventually is executed by means of a rodeo bull-ride.

I saw the Cremaster cycle at the end of summer 2003, when it ran at one of Madison’s art cinemas, the Orpheum. It was a pretty strange venue for this work, since in its heyday the old picture palace once ran Fred and Ginger movies. The Sunday I went, the entire cycle was screened in numerical order. I thought that some installments were very engaging, especially no. 5, a sort of operatic music video set in Budapest. Most of the others offered quite arresting imagery but seemed to me protracted and overbearing in their symbolism. By the end of the day my own cremaster was protesting.

Watching Cremaster 2 last Thursday, I was again absorbed by its imagery and, alas, still resisting the clanking machinery through which every figure, gesture, setting, and surreal juxtaposition called out for some Meaning, however elusive. In a tradition that runs back at least to Ulysses, Barney cooks up an interpretive feast for critics. The monstrous book treating the films and the kindred photographs and objects is, like the movies, at once luxuriant and fearsome. It starts with a ninety-page essay by Nancy Spector that explicates the films’ symbolic dimensions. Here’s a sample, from a discussion of Cremaster 4:

machinery through which every figure, gesture, setting, and surreal juxtaposition called out for some Meaning, however elusive. In a tradition that runs back at least to Ulysses, Barney cooks up an interpretive feast for critics. The monstrous book treating the films and the kindred photographs and objects is, like the movies, at once luxuriant and fearsome. It starts with a ninety-page essay by Nancy Spector that explicates the films’ symbolic dimensions. Here’s a sample, from a discussion of Cremaster 4:

The Loughton Ram, with wool dyed red and all four horns decked in ribbons of yellow and blue Manx tartan, stands at this junction—a symbol for the total integration of opposites, the urge for unity that fuels this triple race. But before the three entities—Candidate, Ascending Hack, and Descending Hack—converge, the screen goes white and silent. This blankness bespeaks the annulment of desire. (63)

Just what I’d feared: every little movement has a meaning all its own. In addition, the essay’s prose style is forbidding in its rodomontade.

With his simple diagram of the field emblem Barney libidinizes architectural space and the surrounding environs, which come to represent the externalization or materialization of inner drives (8).

Surrounding environs, as opposed to non-surrounding ones? Inner drives? What would outer drives be? As for the sentence’s meaning, couldn’t one simply say that “The emblem makes erotic drives manifest”?

Three Thoughts

Anyhow, I just wanted to use today’s blog to externalize, or materialize, or maybe even libidinize, three hypotheses about Cremaster 2.

1. It is Big Art, All-Enveloping Art. It wants to meld many systems of meaning: religion (Mormonism, Judaism), science (fetal development, geological change), history (the Columbian exposition, Gilmore’s killing spree), literature (Mailer’s novel), and more. In this it belongs to a tradition of omnivorous artworks, from Ulysses and Finnegans Wake down to Pynchon, Syberberg, and Greenaway. The artist as demiurge, creating a master-scheme whose correspondences radiate out to many cultural systems: Eisenstein may have been the first filmmaker (in his unmade Moscow project) to attempt something on this scale, but he wasn’t the last.

At the same time, Postmodernist art characteristically absorbs these vast systems in an oblique way, through roundabout citation. I think of Robert Wilson’s Theatre of Images and his collaboration with Philip Glass on Einstein on the Beach. In a rarefied arena, obscure or trivial actions are played out, mysteriously referring to historical events or other artworks. If you don’t know the role of trains or violins in Einstein’s life and thought, you’re arrested by the pure juxtaposition. If you catch the cites, or more likely do your outside reading, you’ll discover an associative logic binding the tableau together. The same strategy of obscure allusion is on view in Glass’s theatre piece about Muybridge, The Photographer.

Something similar happens with Cremaster. As Matt Riley pointed out, Barney’s tableaus can tease you into doing research to find connections, however tenuous, among Gary Gilmore and Harry Houdini, or the Mormons and a Sinclair gas station. But to his grand synthesis, Barney has added autobiography. As in the work of Dalí, Cocteau, and Joseph Beuys, veiled references to public history are mixed with wisps from the artist’s life—in this case, an athletic career and modeling in New York. Beuys’ animal fat (recalling his purported plane crash during World War II) finds its equivalent in Barney’s petroleum jelly, used to keep his shoulder pads flexible during a football game.

Something similar happens with Cremaster. As Matt Riley pointed out, Barney’s tableaus can tease you into doing research to find connections, however tenuous, among Gary Gilmore and Harry Houdini, or the Mormons and a Sinclair gas station. But to his grand synthesis, Barney has added autobiography. As in the work of Dalí, Cocteau, and Joseph Beuys, veiled references to public history are mixed with wisps from the artist’s life—in this case, an athletic career and modeling in New York. Beuys’ animal fat (recalling his purported plane crash during World War II) finds its equivalent in Barney’s petroleum jelly, used to keep his shoulder pads flexible during a football game.

These films assign you homework. Fortunately we have cheat sheets. Like Joyce and Greenaway, Barney has explicated his work’s public and private mythology. The bare bones are laid out on the cycle’s official website. Since free-associative interpretation is the modus operandi of most academic criticism, highly associative art like this has the effect of playing to commentators’ strengths. The Cremaster book includes not only Spector’s blow-by-blow explication but also an imposing glossary, with entries running from anus-island to zombie, illuminated by snippets from fiction and literary theory. Barney will keep critics very busy for a long time: Some Cremaster scenes are as iconographically dense as a mannerist Annunciation.

2. Stylistically the films go down like milkshakes. There may be less here than meets the eye, but what meets the eye is pretty gorgeous. The installments have the smooth cutting and meticulous compositions of Cocteau’s Orphée. Their limpid camera movements, swooping helicopter shots, and luscious color design could pass muster in a Hollywood production. The films flaunt their production values, and you could argue that this can make them attractive to young people who might find rougher-edged or lower-budget experiments by Ernie Gehr or Lewis Klahr harder to take. Though the shots run moderately long (averaging 9-10 seconds in the films I clocked), the insistence on close-ups, arcing camera, and slow zooms recalls that cluster of current Hollywood techniques I’ve called “intensified continuity,” and this helps contemporary audiences concentrate on the tableaus.

Another user-friendly aspect, touched on in the panel discussion: The echoes of the horror film. We’re on edge from the start of Cremaster 2, with Jonathan Bepler’s rumbling score rising dissonantly as the bleeding logo hurtles out at us, looking like a thorny torture device. The dripping nose and bolted mouth of Baby Fay la Foe, the bees swarming over the thrash-rock musician as he makes a call, and the bloody body of the gas station attendant offer us some fairly pure horror-movie iconography. It could just as easily be called Creepmaster.

Another user-friendly aspect, touched on in the panel discussion: The echoes of the horror film. We’re on edge from the start of Cremaster 2, with Jonathan Bepler’s rumbling score rising dissonantly as the bleeding logo hurtles out at us, looking like a thorny torture device. The dripping nose and bolted mouth of Baby Fay la Foe, the bees swarming over the thrash-rock musician as he makes a call, and the bloody body of the gas station attendant offer us some fairly pure horror-movie iconography. It could just as easily be called Creepmaster.

3. Might not this be the Artworld’s parallel to a Hollywood blockbuster franchise? The Cremaster films are designed chronologically, like sequels are. They have spawned fan videos and fan music. They spin off ancillaries, such as the souvenir volume I’ve already mentioned, along with T-shirts, baseball caps, and coffee mugs. Since this is the Artworld, though, the real ancillaries are the photographs, drawings, and sculptures that tour on exhibit. In early 2004 one photo triptych from Cremaster 2 fetched over $186,000. The film has become a precious object in itself. Only ten institutions, we’re told, can acquire prints, and the series won’t be released on DVD.

Those who think that many contemporary museum shows are really about the shop will find strong evidence here. In today’s art market, Cremaster might be the gallery scene’s equivalent of the summer megapicture, the project that by virtue of its monumental scale and production values generates income at many levels indefinitely. Again, the showmanship of that adroit impresario Dalí comes to mind.

From this perspective, Barney becomes the equivalent of an A-list movie producer or director, overseeing a platoon of artisans like Matt Ryle who bring his vision to life. Cremaster reminds us of the ambiguities in the word studio, applied both to moviemaking and the fine arts. For hundreds of years successful painters have in their studios divided the labor of artmaking, planning the overall design and assigning juniors to fill in bits before the supervisor added his distinctive touch. Warhol revived this in ironic mode with his Factory, often by denying he had a touch by leaving all the work to others. But Warhol’s films struck observers as crude and offhand, while Barney has produced something bold, polished, and overwhelming. If Warhol was the Roger Corman of the Artworld, Matthew Barney may be its Jerry Bruckheimer.

PS: In correspondence Professor Jim Kreul has called my attention to an article that anticipates my third point: Alexandra Keller and Frazer Ward, “Matthew Barney and the Paradox of the Neo-Avant-Garde Blockbuster,” Cinema Journal 45, 2 (2006), 3-16. It considers in detail the relationship of Barney to performance art as well.

Welcome back, Suo-san

Suo Masayuki, one of Japan’s most ingratiating directors, found an international triumph with Shall We Dance? (1996). He had started his career with an odd little softcore porn film, Abnormal Family (1983), shot as an admiring pastiche of Ozu’s style. His Fancy Dance (1989) was also fun, but he really hit his stride with Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (1992), which remains a sure-fire crowd pleaser.

Suo worked comic variations on an ingenious theme: How Japanese youth fail to appreciate the beauty of their traditional culture. The garage-band ska singer in Fancy Dance is obliged to retreat to a monastery, where he discovers that Zen is really, really cool. Sumo Do converts sullen college kids to the virtues of ritualized wrestling. Shall We Dance? works in reverse, obliging an uptight salaryman to rekindle his marriage by learning ballroom dance. Suo’s films celebrate pleasurable fusions between Asian and Western cultures.

Suo’s meticulous, understated style is a kind of modern revision of Ozu’s. Fancy Dance and Sumo Do pay homage to the master’s college comedies, and in Shall We Dance? the first tracking shot occurs when the hero takes his first tentative dance steps. In Figures Traced in Light, I mention Suo as part of that trend toward planimetric shooting and compass-point cutting I discussed in an earlier blog. As you see from the opening images, he tries out the precise sort of graphic matching between shots that was a hallmark of Ozu’s style.

Suo has been very quiet for the last decade, but now he’s back. I Just Didn’t Do It is arousing keen local interest, partly because of its controversial subject matter. Japan is known as a low-crime society, but gradually questions of police brutality have emerged. Suspects can be kept in custody for up to 23 days, and unique among industrial nations, 95% of all people arrested confess!

Suo has been very quiet for the last decade, but now he’s back. I Just Didn’t Do It is arousing keen local interest, partly because of its controversial subject matter. Japan is known as a low-crime society, but gradually questions of police brutality have emerged. Suspects can be kept in custody for up to 23 days, and unique among industrial nations, 95% of all people arrested confess!

In Suo’s new film, a young man is accused of groping a schoolgirl in the subway. It’s a daring move for a director known for light comedies. The film stars Kase Ryo, from Letters from Iwo Jima, and veteran Yakusho Koji, seen most recently in Babel. Read more about it here, noting that the Economist’s contents tend to evaporate into the pay-only archive. The film’s official website, in English, is here.

I Just Didn’t Do It, Suo says, is a film “I simply had to make.”