Archive for September 2007

Back in Vancouver

DB again:

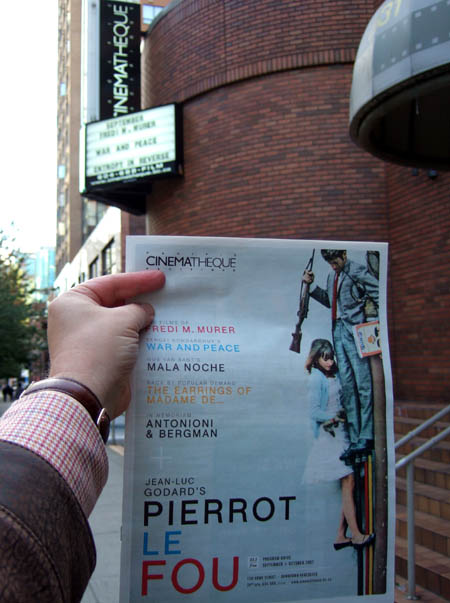

I sang the praises of the Vancouver International Film Festival in my first venture into blogging a year ago, so it’s a pleasure to report that this year’s event is no less captivating. Too many movies to take in, natch, so I’ll concentrate on two of the fest’s great strengths, documentaries and Asian films (programmed this year by both Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer). Top and bottom of today’s entry: glimpses of the two venues where I spend the most time: the Empire Granville 7 multiplex and the Pacific Cinémathèque a couple of blocks away, the latter offering ambitious programming to gladden the heart of any cinephile.

Two docus

10 + 4 (Iran) provides vignettes of Mania Akbari’s struggle to live with cancer therapy. The fact that she’s also the filmmaker, and that she starts, at Kiarostami’s suggestion, from the visual premise of 10, gives the film extra layers of interest. In fewer than seventy shots, most from within moving vehicles, the film presents a series of dialogues, usually between only two people. Since most major action takes place elsewhere, we watch and listen for signs of characters’ pasts, their relationships, and their states of mind.

We can trace Akbari’s development from cheery pride, going to parties despite her chemotherapy (“Every morning I thank God for make-up”), to anguish as the pain mounts and the treatments intensify. No viewer will forget the scene on a cablecar when she and Behnaz, from 10, reveal their different responses to their illness, and offscreen, examine each others’ mastectomies. In a final scene, Akbari, her hair now regrown, is confronted by another woman who warns her of using cancer as a weapon. The final words, heard under the credits—”I am using it, and I can’t give up the joy of this game”—reveal a psychological insight we rarely find in discussions of the social implications of illness.

Oatmeal-video visuals shot handheld and often out of focus, talking heads, dicey sound, overbusy editing—never mind. My Kid Could Paint That shows that we’ll forgive all sorts of technical faults if the subject, story, and ideas are gripping.

At one level, Amir Bar-Lev’s film simply traces how four-year-old Marla Olmsted was catapulted to celebrity when her dribbly paintings became collector’s items. Bar-Lev was lucky enough to be around Binghamton from more or less the start of her strange adventure, and he gained the family’s confidence. Soon enough, though, Bar-Lev is asking exactly how these paintings could wriggle into the artworld.

At one level, Amir Bar-Lev’s film simply traces how four-year-old Marla Olmsted was catapulted to celebrity when her dribbly paintings became collector’s items. Bar-Lev was lucky enough to be around Binghamton from more or less the start of her strange adventure, and he gained the family’s confidence. Soon enough, though, Bar-Lev is asking exactly how these paintings could wriggle into the artworld.

It’s partly because, he shows, experts are pretty evasive when it comes to explaining how to tell good abstract painting from bad. Can’t you tell just by looking, as we can when we appreciate the figurative work of old and new masters? Turns out it’s not so easy. Critic Michael Kimmelman suggests, somewhat vaguely, that even abstract art is about a “story”—if not in the picture, behind the picture. Marla, of course provides a great story, but the question of how to judge her oeuvre remains.

We might insist that an artwork’s goodness is intrinsic, regardless of the circumstances of its making. If we learned on good evidence an eighty-year old woman had composed The Marriage of Figaro, surely it wouldn’t lose its sublimity. But philosophers Arthur Danto and Denis Dutton have suggested that our information about how an artwork came to be is usually relevant to interpreting and judging it. Sure enough, collectors rhapsodized about the work when they thought Marla had done it, but they cooled after a 60 Minutes story suggested that the father had coached her, and perhaps even finished the pieces himself.

That raises another issue, encapsulated by a Binghamton journalist. She explains that if a story is to run long in the media, it has to be given steep ups and downs. Hyped at the start, Marla’s paintings are suddenly called con jobs, and even Bar-Lev starts to get doubtful. How the family tries to regain their credibility, and how Bar-Lev exposes his own hesitations and complicities, makes for a fascinating film.

My Kid Could Paint That touches on other matters, such as the world’s love of a prodigy, the money that drives the gallery scene, and the issue of how much craft, such as skill in drawing, we now demand of our artists. What shines through the intellectual issues is a childhood joy in picture-making. As portrayed here, Marla remains a kid, and she reminds us of the pleasure in gooping up a surface with our fingers. Sony Pictures Classics made a wise move in acquiring this engrossing movie.

Turning Japanese

I try mostly to blog about films I like, passing over the others in silence. Hammer jobs are fun to write and to read, and I confess to having indulged in a couple when I felt that historical or stylistic analysis could cast light on current films that were being overpraised for originality. By and large, though, I prefer what Cahiers du cinéma called the criticism of enthusiasm. Everyone should write about the films she admires, and let history sort them out.

But my admiration for Kitano Takeshi has been so great since I saw Sonatine back in the 1990s that I can’t let Glory to the Filmmaker! pass without a little comment. His previous foray into fake autobiography, Takeshis’, seemed to me pleasant enough in a casual way. Unless I’m missing something, however, Glory to the Filmmaker! is an unmitigated embarrassment. Gone are the surprising compositions and subtly daring cuts; gone too the elliptical narrative that has time for adolescent digressons. Glory! is nothing but adolescent digressions, sketches and skits that either cling to an unfunny premise, like the dummy Kitano that pops up now and then, or abandon their premises halfway through. The pastiches of Ozu and Kurosawa are slapdash and inexact, while the more purely Kitanoesque stretches work at very low wattage.

But my admiration for Kitano Takeshi has been so great since I saw Sonatine back in the 1990s that I can’t let Glory to the Filmmaker! pass without a little comment. His previous foray into fake autobiography, Takeshis’, seemed to me pleasant enough in a casual way. Unless I’m missing something, however, Glory to the Filmmaker! is an unmitigated embarrassment. Gone are the surprising compositions and subtly daring cuts; gone too the elliptical narrative that has time for adolescent digressons. Glory! is nothing but adolescent digressions, sketches and skits that either cling to an unfunny premise, like the dummy Kitano that pops up now and then, or abandon their premises halfway through. The pastiches of Ozu and Kurosawa are slapdash and inexact, while the more purely Kitanoesque stretches work at very low wattage.

Kitano is such an important filmmaker that you can’t ignore even something as offhand as this, but we have to hope for more.

Ten Nights of Dreams, a portmanteau feature based on stories by Soseki Natsume, is as uneven as these affairs usually are. The first chapter, a lovely episode by Jissoji Akio, is eerie in a subdued way, with some quietly canted compositions and some cutting reminiscent of the great Page of Madness. I also enjoyed Ichikawa Kon’s entry, a sober monochrome exercise. Most of the others, however, rely on turbocharged CGI and frantic grotesquerie—all justified by the indulgent premise that dreams are really, really weird.

Yamashita Nobohiro’s Matsugane Potshot Affair (2006), however, bowled right down my center lane. A crooked couple comes to a small town and their search for stolen bullion becomes one thread in a tangle of dysfunctional families and grubby sex. My last sentence does the film an injustice, though, because the laconic narration fills in the circumstances and backstory at such a leisurely pace that all your attention is on the grim comic byplay and furtive eroticism of the townfolk. Any movie that starts with a little boy feeling up what appears to be a woman’s corpse on a frozen lake signals its tone pretty straightforwardly.

As in Linda Linda Linda, the only other Yamashita I’ve seen (and mentioned here), the staging and shooting are quietly commanding. The shots average about 23 seconds, but they seem longer because the camera almost never moves. Lovely long takes with layers of depth and pockets of action captured in windows and paper doorways recall the great Japanese tradition of all-over composition. Yamashita provides several shots that could be filed in my gallery of funny framings. When you film this way, you have to know exactly where to put the camera, and several scenes—notably a confrontation among the thieves and the twin brothers—quicken areas of the frame we never normally notice. Movies like this remind you of the pleasure of having time to see everything.

I haven’t yet mentioned the film I enjoyed most, Jiang Wen’s The Sun Also Rises, and today I’m also seeing the new Suo (I Just Didn’t Do It) and some other enticing items. So I turn Chinese, and Japanese again, in my next entry.

For more blogs anchored to the festival offerings, go here.

Our first anniversary, with a note on the unexpected fruits of film piracy

DB here:

This blog started on 26 September 2006. During its first year, it has attracted over 400,000 pageloads, over a quarter of a million visitors, and over 50,000 returning visitors. We currently average about 1000 visitors a day. While this is small potatoes by the standards of mammoth websites, it’s far more than we expected when we started. We’re grateful to all those readers who sought us out or stumbled upon us, who Googled and Yahoo’d us, who linked and listed us, who sent us corrections and extra information. And we’re grateful to our web tsarina Meg Hamel who set this up and keeps things running smoothly.

In the last twelve months, we’ve posted about 200,000 words, or enough for two books. We’ve tried to make most entries as attentive to ideas and information as what we’d write for a print publication—if not a scholarly book, at least a mainstream article. Kristin and I think of our blog as a sort of column, published in a magazine we edit, with no length restrictions, no assigned topics, and as many pictures as we like. It’s been fun to write more informally than we usually do. We’ve also been able to call attention to regional and national cinemas (e.g., Hong Kong, Denmark, New Zealand) we think deserve more attention. We can also pursue topics that we couldn’t fit into larger research projects, like Kristin’s interest in the Lord of the Rings franchise and my curiosity about alien autopsies.

While the blog originally aimed to supplement Film Art: An Introduction, we think that the best way to do that is to keep reminding our readers that the world of film is dazzling in its diversity and unpredictability. One commentator said that our blog was aimed at students and nonspecialists, but we find that many professional film scholars and film journalists check on us. Perhaps that’s because we wander where we like, from very old films to recent films we see at multiplexes and festivals, and we propose ideas that could be considered more closely and researched more exactingly. One correspondent said that many of our entries could be the basis for research articles. Maybe, but we have more ideas than we can ever write up systematically, so off to the blog they have gone. In addition, we’ve sometimes used the blog to extend or supplement things we’ve published in books and articles.

Looking back at what we’ve done, I notice some recurrent themes.

*In keeping with the blog’s title, we emphasize film as an art form. More specifically, we’re especially interested in how structure and technique work together, which few blogs outside the industry do. For instance, most online critics have concentrated on praising or condemining The Brave One, and in rather general terms. If we wrote about it, we’d probably focus on the effects of its alternating points of view, its use of the four-part script structure, and its recourse to oddly rocking camera movements to convey Erica’s disorientation at crucial moments (and trace how those develop in patterned ways across the film). That is, we’d incline toward somewhat finer-grained analysis of cinematic storytelling, even if that means going shot by shot. If we want as well to make an evaluation of the film, as we sometimes do, we then have some concrete evidence to back it up.

*We also treat film art as tied to film commerce—both the mainstream industry and the less-acknowledged form of commerce known as film festivals. We’ve always believed that there isn’t necessarily a battle between film as an art form and “the business.” Much of our published work, including Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment and my work on Hong Kong film and contemporary Hollywood, as well as our collaboration with Janet Staiger on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, tries to trace out ways in which funding affects the look and feel of the finished work. Money matters!

*We’re happy to find that a lot of filmmakers read and link us. One of the purposes of Film Art was to show how artistic expression in cinema is tied to practical decisions made by filmmakers; that’s why we begin the book with an overview of the process of film production. In our academic work as well, we’ve been more inclined than most scholars to interview filmmakers, to read technical journals, and to study how craft practices create artistic effects. We’ve developed friendly relations with Asian filmmakers like Johnnie To and American filmmakers like Mark Johnson and James Mangold. We’ll continue to discuss how technique, technology, and filmmaking traditions interact in cinematic expression.

*We’ve tried to deflate some clichés of mainstream film journalism. Writers of feature articles are pressed to hit deadlines and fill column inches, so they sometimes reiterate ideas that don’t rest on much evidence. Again and again we hear that sequels are crowding out quality films, action movies are terrible, people are no longer going to the movies, the industry is falling on hard times, audiences want escape, New Media are killing traditional media, indie films are worthwhile because they’re edgy, some day all movies will be available on the Internet, and so on. Too many writers fall back on received wisdom. If the coverage of film in the popular press is ever to be as solid as, say, science journalism or even the best arts journalism, writers have to be pushed to think more originally and skeptically.

*There’s the theme we might call the continuing presence of the past. I notice that many of our entries comment on a current event or topic by showing that it has parallels and precedents in earlier periods of film history. This isn’t, I hope, showoffishness or academic point-scoring or a bored conservatism. Often this historical awareness allows us to correct hype and nuance ideas. Yes, today’s cinema experiments with flashbacks and intersecting story lines; but these are formal strategies we find in earlier periods of filmmaking too. So the interesting questions become: How are today’s strategies different? Why do these traditions get reinvented now? What consequences do they yield in our current circumstances? Rather than celebrating apparent innovation, it’s more exciting to see how filmmakers connect to tradition, shaping it in ways that even they might not be aware of doing. We tend to see the present through a narrow window, but historical awareness widens and deepens the view.

We rethink our project from time to time. Regular readers will notice that we’ve just added a roll of Readers’ Favorite Entries, on the right. We’ve also talked about adding a podcast to the site. In any event, we look forward to another year of our little magazine, and we have a folder full of ideas that we hope will tantalize you.

I’m off to Vancouver to cover the festival, as I did a year ago. More information on its wonderful lineup is here. In the meantime, some dessert.

Piracy ahoy

In Shanghai a few years ago I visited a shop selling pirated DVDs. Two illegal titles caught my eye.

According to the Motion Picture Association of America, the trade association of the major Hollywood companies, all pirated editions have their origin in camcorder copies made during screenings. In other words, it’s those outlaw consumers ripping us off.

But a large part of piracy can be traced to people working inside the industry. A common source is the raft of DVD screeners sent out to Academy members during awards season. It has proven impossible to keep these discs from getting into the hands of pirates. Other bootleg copies come from inside the production and distribution companies. Famously, a copy of Bulletproof Monk surfaced in China before the final cut was made; it’s widely believed that an employee leaked it. With so many special-effects houses working on a film in postproduction, it’s not difficult for one keyboard jockey to upload a working copy to the Darknet. Hence all those time-coded versions of the Star Wars saga that made their way into eager fans’ hard drives.

Further evidence of this tendency comes from the first Shanghai DVD I examined, that of The Passion of the Christ, not then available legally anywhere. It was a curious copy. It was an auditorium version, as pirates call movies snagged during a screening. The color and resolution were poor, and the camera zoomed in during the credits to a 1.75 ratio, wrecking the anamorphic compositions and creating closer framings.

Poor as it was, the bootlegged disc lacked some of the usual problems. The image was stable and centered, with no sign of being filmed from a seat in the house. The sound wasn’t tinny or boomy, as it would be if it came from theatre speakers, but it was plagued with whistles and dropouts.

I concluded that this was a version made by a projectionist in off-hours. He or she had time to set up the camera on a tripod near the back of the house and record the whole film without distraction, using an iffy sound feed. But what was more puzzling was the fact that the print being screened had no subtitles.

So what I was seeing was an early version, before any subtitles had been put on. The projectionist wasn’t your local multiplex employee but someone in the postproduction process. In a way, however, this bootleg copy fulfills Mel’s dream. As the film began shooting Mel claimed:

Obviously, nobody wants to touch something filmed in two dead languages. They think I’m crazy, and maybe I am. But maybe I’m a genius. I want to show the film without subtitles. Hopefully, I’ll be able to transcend language barriers with visual storytelling. If I fail, I’ll put subtitles on it, though I don’t want to.

On the bootleg DVD you could add Chinese titles or barely comprehensible English ones. Of course once the official DVD version came out, you could turn all subs off, but for a moment the bootleg market had given us Mel’s vision pure.

The second DVD that caught my eye points up another unexpected consequence of piracy. The cover of the release is at the very top of today’s entry. What made me investigate was the fact that Michael Caine is listed as being in the movie twice (though with different Chinese characters giving “his” name). Even the eager young researcher of PCU, immersed in the oeuvres of Gene Hackman and Michael Caine, might want to add a paragraph about this movie.

The credits on the back of the package add to the confusion. They are for Disney’s The Kid, and the running time is listed at 2:49. (The Kid is only 104 min.) I later learned that The Kid is a default paste-in on many DVD backsides. Why reproduce several different credit lists when all that matters is the metamessage, “This is an American movie”? But if it’s a Disney film, why does the printing also provide the Universal logo and an R rating?

So I broke down and watched the movie. (Flawless copy, by the way.) It is Code 11-14, a 2001 TV movie by Jean de Segonzac (big clue on the cover). An LA cop is tracking a serial killer. The killer follows the cop and his family onto a passenger jet and terrorizes them. According to Hal Erickson’s All Movie Guide, CBS pulled it from the schedule in the wake of 9/11. It wasn’t broadcast until 2003. Code 11-14 stars David James Elliott, Nanci Chambers et al., but not Michael Caine.

These sorts of mind games are pleasant. It’s fun to be thrown off balance by guessing how the credits got scrambled (PhotoShop set to Random?) and why Mr. Caine is credited doubly. Is he twice as popular in China as any other actor?

But the strongest justification for the existence of this pirate copy seems to me the liner notes.

What you see on the cover above—England movie circles cluster animportant history for but moving—is but a foretaste of what you find on the back. I reproduce it word for word.

This large war movie, empty cluster in the movie circles elite of England but move, for re-appear their motherland atAn important history of the period of World War II but worker harder, the film to record theatrical breeze The space describes the German Nazi in 1910 got empty bomb British intensive metropolis, make England Lose miserably heavy, but also arose England people together enemy spirit to make Germany, in numerous Popular actor inside, exceed the gram. The boon of . The willing to thinks, the shares the drama more, play the cuckoldry of The jade of Susan then expresses romantic, in addition, the Lawrence the brilliant jazz in military tactics with, the plays the plays the heartless condition in hungry clap very sublime and lifelike.

Exactly. I rest my case.

PS 30 Sept: I should’ve realized there’d be a website devoted to maniacal pirate prose and pictures. Thanks to Stuart Ian Burns, I learn that you can find many more at a Flickr group called, logically, crappy DVD bootleg covers.

Beyond praise: DVD supplements that really tell you something

Filming The Da Vinci Code in the Louvre.

Kristin here—

In the 8th edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we added a feature, “Recommended DVD Supplements.” Most chapters end with one of these, which contains information about relevant supplements that might be useful to teachers and students. Filmgoers outside the classroom might find them helpful as well.

As we all know too well, many DVD supplements consist largely of interviews with the main cast and crew members in which they praise each other. (“I don’t know how we could have made this movie without _______. She was perfect for that part.” “We were lucky to be working with a director who’s a genius.”) Not very interesting. We try to sort through and find supplements where the filmmakers actually talk in an informative and entertaining way about how they went about their work.

Obviously many DVDs have come out since we finished our last round of revisions, so we plan to use this blog as a means of occasionally updating our recommendations. Your suggestions about especially informative supplements are welcome.

King Kong (Deluxe Extended Edition, Universal)

In Film Art 8, I recommended the Production Diaries Peter Jackson put together for King Kong, since they cover (albeit briefly) a lot of topics that few supplements tackle. One day’s diary entry is devoted entirely to clapperboards! In the extended King Kong DVD, some of the additional supplements also deal with topics that most DVD’s extras bypass.

In relation to the section on settings in the Mise-en-scene chapter, for instance, you might look at “New York, New Zealand” (23 minutes). While most descriptions of CGI talk about how it is used to make monsters or crowds, this supplement discusses how the creation of settings can depend on digital imagery (above). During the fairly lengthy (42 minutes) documentary, “Pre-Production: The Return of Kong,” there is a discussion of what a First Assistant Director does during during this phase of production (40 minutes in). How often do you run across that? It could be used in conjunction with our layout of production roles in Chapter 1.

The 30-minute “Return to Skull Island” section goes into miniatures, matte paintings, and green-screen work—things that are often featured in supplements. This one also covers a less familiar technology, digital doubles.

Far from Heaven (Universal)

Supplements that examine a single scene, technique by technique, are pretty rare. One of the supplements on the Far from Heaven DVD does so in a useful way. The track originated as a documentary, “Anatomy of a Scene,” produced by the Sundance Channel (27 minutes). The analysis covers the production design and costumes, cinematography, acting, editing, and music. At the end, the completed scene is shown. The other large supplement on the disc, “The Making of Far from Heaven,” discusses the filmmakers’ attempts to replicate a 1950s look. It’s rather bland, with a little on style, a little on ideology, and a lot of mutual praise.

The Da Vinci Code (Sony; all editions have the supplements)

The DVD of The Da Vinci Code has two useful supplements. “Magical Places” (16 minutes) is an excellent demonstration on the logistics of going on location: permissions needed, technical challenges (such as lighting real interiors), and the substitution of one real building for another. Students will gain an awareness that even in real locales, filming doesn’t mean just going out, aiming a camera, and shooting stuff.

The second, “Filmmakers’ Journey Part One” (24.5 minutes) is not as good but still interesting. It could be used in conjunction with our Chapter 3, “Narrative as a Formal System,” which is rather hard to find relevant supplements for. There is discussion of character, timing, and rhythm. One passage that is particularly good for showing how filmmakers think about the form of films comes in a segment on the introduction of a major new character (Sir Lee Teabing) fully halfway through the film. Moreover, as director Ron Howard says, the Chateau Villette scene in question is a “high-wire act,” with a great deal of exposition suddenly brought into the middle of what has largely been an action-filled chase film. There is also discussion of the film’s series of journeys: “There was this sort of classic structure that we were working with.” It’s a pattern we discuss in Chapter 3. If nothing else, this supplement might convince students that their textbook’s authors are not just making up these terms to bedevil them!

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest ( Disney, 2-disc Special Edition)

Unexpectedly, one of the best sets of supplements I’ve seen lately accompanies Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest. It’s a film that I mildly enjoyed watching, but I liked the making-of documentaries more. For one thing, the style is unusually low-key and lacks the chat about how wonderful everyone and everything was.

“Charting the Return” (about 26 minutes), for example, follows the stages of pre-production not just through interviews but also via a fly-on-the-wall presence of the camera at meetings and discussions. Often the people onscreen are not being interviewed but are actually at work, talking to each other. We see scripting, location scouting, design, and scheduling. Problems with deadlines and budgets are discussed rather than glossed over. The candor makes for a surprisingly entertaining and informative little movie. The same is true for “According to Plan” (60 minutes), which covers principal photography. Crew members delight in the beautiful Caribbean locales–but also complain about the heat, humidity, tides, rocking boats, and roads too small for equipment trucks. It’s one of the few accounts I’ve seen that suggests both the joys and the frustrations of real filmmaking.

Unless you’re really, really interested in costuming—or in ogling Jack Sparrow—the “Captain Jack: From Head to Toe” is frivolous. The “Mastering the Blade” segment can be skipped as well.

“Meet Davy Jones” (about 12 minutes) describes an important development in motion-capture technology for creating CGI characters. “Image-based motion capture” can extract mocap markers from a two-dimensional image (e.g., a shot of an actor performing on a stage) and make it three-dimensional. It can then be manipulated and placed back in the shot. In a discussion of modern special effects, this supplement might usefully be compared with the ones about the creation of Gollum in the Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers extended DVD set. The “Creating the Kraken” film (10 minutes) explains well how practical and CG special-effects are blended.

Filming as the tide covers the island used as a location.

You can skip the “Fly on the Set: The Bone Cage” segment, which is a skimpy four minutes on blue-screen special effects and the use of multiple cameras. OK, but this topic is covered more thoroughly on other films’ supplementary discs. Beware of “Jerry Bruckheimer: A Producer’s Photo Diary.” Bruckheimer makes up for all the compliments to director, cast and crew that were left out of the other supplements in this mercifully brief (5 minutes) track.

Unfortunately, some of the best recent films have come out on DVD with no supplements to speak of. When will we see some extras-laden editions of Cars and Zodiac?

[September 24: Film critic Kent Jones tells us that a deluxe DVD edition of Zodiac is coming out in the near future.]

The sarcastic laments of Béla Tarr

Werckmeister Harmonies.

DB here:

Last weekend, Facets MultiMedia in Chicago held a tribute to Béla Tarr. Milos Stehlik and his colleagues have been long-time champions of Tarr’s work, holding retrospectives and releasing nearly all his features on DVD (with Sátántangó soon to come). Tarr arrived on Saturday, but an emergency sent him back to Hungary sooner than he expected. So instead of discussing his work with a panel, he could only introduce the screening of Werckmeister Harmonies before running off to the airport.

The panel went ahead, with Jonathan Rosenbaum, Scott Foundas, and me chatting with Susan Doll of Facets. It wasn’t as pungent a session as it would have been with Tarr there, but I thought it was still pretty interesting. Jonathan, Scott, and Susan had thoughtful comments, and the questions from the audience were exceptionally good. The whole session was recorded for an online broadcast at some point, so you might want to watch out for that. And I have earlier blog entries on Sátántangó here and here.

In preparation for the panel I spent last week reconsidering Tarr’s work, so I offer a few notions about his films and how we might place them in the history of cinematic form and style. Some of these remarks build on things I said at the session.

Up close and personal

Some directors accommodate critics, accepting or at least tolerating writers’ efforts to probe the work. Not Tarr. Ask about his plots and characters, and he claims that he doesn’t tell stories. Point out what seem allegorical or symbolic touches, and he protests that he doesn’t make allegories and he hates symbols. Mention contemporary cinema, and the reply is abrupt: “For me, when I see something at the cinema it is always full of shit.” And if you tell him that his early films seem quite different from his more recent ones, he vehemently disagrees.

Some directors accommodate critics, accepting or at least tolerating writers’ efforts to probe the work. Not Tarr. Ask about his plots and characters, and he claims that he doesn’t tell stories. Point out what seem allegorical or symbolic touches, and he protests that he doesn’t make allegories and he hates symbols. Mention contemporary cinema, and the reply is abrupt: “For me, when I see something at the cinema it is always full of shit.” And if you tell him that his early films seem quite different from his more recent ones, he vehemently disagrees.

As Scott pointed out in our panel, though, it can be plausible to apply the concept of “period” to filmmakers’ work as we do to painters’ careers. Lars von Trier has been fairly explicit that after mastering a polished style for his work up through Zentropa/ Europa he wanted to try something new, and with The Kingdom he shifted toward a looser, on-the-fly style that pointed toward Dogme 95. Any viewer can be forgiven for thinking that Tarr has moved in the opposite direction of von Trier, from a pseudo-documentary approach toward something much more grave and majestic.

The first three theatrical features focus on the urban working class and their struggles to improve their lot. In Family Nest (1979), a family who can’t afford a flat of their own squeezes in with the husband’s parents. The tight quarters, the ceaseless complaints of the father-in-law, and the husband’s inertia force his wife and child to flee to the streets. The Outsider (1981) follows a young violinist as he drifts among jobs and into a passive marriage before being called up for military service. The family in The Prefab People (1982) has a flat and a decent job, but the wife finds the husband indifferent to her boring routines, and he looks for an escape in a job in another town. The concentration on ordinary people’s lives and the search for drama in the everyday dissatisfactions of city life put the films in the neorealist line of succession.

Stylistically, the films are stripped down in ways that also owe debts to modern traditions. Shot mostly handheld, adjusting the framing to the actors’ performances, they belong to a strain of films from the 1960s on that sought to suggest the immediacy of cinéma-vérité documentary. Unlike many such films, however, Tarr’s buy into a long-take aesthetic. Perhaps surprisingly, these movies’ shots run abnormally long: an average shot length of 32 seconds for Family Nest, 33.5 for The Outsider, 47 seconds for Prefab People. By comparison, Hollywood films of these years were consistently running between 4 and 8 seconds per shot, and comparatively few European and Asian films rely on shots as lengthy as Tarr’s.

Most scenes in these three films are dialogues, and the camera holds intently, if shakily, on faces. This concentration is enhanced by the general absence of establishing shots. A scene opens more or less in the middle of a conversation, and we get a character already challenging another. The visual pattern is that of shot/ reverse-shot, and in most scenes the first face is counterposed to a second one by either a cut or a pan. Shooting on location in cramped rooms, Tarr makes his framings tight; in Family Nest, the jammed frames give us and the characters almost no breathing space.

By relying on more or less isolated faces in close-ups, Tarr can absorb us in the intimate drama while sometimes catching us off guard. For instance, when we get a single character without an establishing shot, there is often a momentary uncertainty about where we are, or when the action is taking place. We also can’t be sure of who’s present besides the speaker, so the close view of him or her leaves us hanging: To whom is s/he talking? We’re pushed to pay close attention to what the character is saying, looking for any clues to the dramatic context. Tarr’s tactic also delays the reaction of the listener; he may withhold sight of the conversational partner until s/he speaks. The effect, heightened by the lengthy takes, is to turn many of these scenes into monologues, in which a character pours out his or her reaction to a situation, and we’re forced to take that in more or less pure form.

By the end of Family Nest, Tarr is shooting entire scenes concentrated on a single face, and because we don’t know if there is anyone else present, we have to take the talk as virtually a soliloquy.

It’s as if Tarr invoked the stylistic schema of shot/ reverse shot and simply postponed or suppressed the reverse shot, leaving only an inexpressive shoulder in the foreground, if that. I’ve discussed the delayed reverse-shot as a convention of European cinema in an earlier blog, and Tarr makes ingenious use of it.

Tarr builds these films out of conversational blocks, punctuated by undramatic routines. The result is that often major plot actions take place offscreen, or rather in between the dialogues. Exposition that other filmmakers would give us up front is long delayed, with bits of information sprinkled through the entire film. In Family Nest, the father claims that he’s seen Iren having an affair with another man. We can’t be sure he’s lying because we haven’t strayed enough out of the household to judge her activities. In The Outsider, one scene ends with the drifter Andras telling Kata, a woman he has recently met, that he has a child by another woman. The scene ends with him smiling in indifference, leaving his sentence unfinished. In the next scene, a band strikes up a tune: Andras and Kata are celebrating their marriage.

Most filmmakers would show us more of the courtship and a scene of proposal, but Tarr moves directly to the next block, suggesting Andras’ laid-back heedlessness. Agreeing to get married is no big deal. Further, by skipping over the most obviously dramatic incidents, Tarr’s storytelling joins that tradition of ellipsis celebrated by André Bazin in his essays on neorealism. No longer does the filmmaker have to show us every link in the causal chain, and no longer are some scenes peaks and others valleys. By deleting the obviously dramatic moments, the filmmaker forces us to concentrate on more mundane preambles and consequences.

This block construction yields an unusually objective narration. These films lack voice-overs, subjective flashbacks, dreams, and other tactics of psychological penetration. We have to watch the people from the outside, appraising them by what they say and do. It is a behavioral cinema. True, Prefab People opens with a flashback: The husband is packing to leave his wife, and the plot moves back to an anniversary dinner that ends badly. But the flashback to the earlier phase of the marriage isn’t framed as the wife’s memory. When the plot’s chronology brings us back to the moment of the husband’s departure, the replay of the opening allows us to watch the characters with more knowledge of what is driving them apart. Unsurprisingly if you know Tarr’s earlier films, that replay is followed by a long monologue showing the wife expressing her sorrow at his departure, without any visual cues about who, if anyone, is listening.

Then, without preparation, we see the couple back together, shopping in an appliance store. How did they reconcile? Have their attitudes changed, or are they simply reconciled to their old life? Like Antonioni and many other modern filmmakers, Tarr doesn’t tell us such things. He simply ends his film on a long take of husband and wife riding expressionless in the back of a truck, as much pieces of cargo as the washing machine beside them.

After the Fall

The second-phase films do look and feel rather different. Almanac of Fall (1984), a story of duplicity and spite among people sponging off a well-to-do older woman, offers a wholly elegant mise-en-scene. Characters are often framed from far back, surroundings take on much more importance, the framing is stable—often with windows, doors, and furnishings impeding our view of the action—and the camera moves smoothly, often in arcs around stationary figures. The takes are even longer, averaging just under a minute. The rococo lighting (patches of color seem to follow actors around) and atmosphere of strained upper-class narcissism seem like quite a break from the working-class films. If I had to find an analogy to Almanac of Fall, it would be Fassbinder’s Chinese Roulette (1976), with its camera arabesques and slightly decadent ostentation.

The overripe shots of Almanac of Fall signaled a shift toward a self-consciously formal cinema, but then Tarr stripped his settings and cinematography down. From Damnation (1988) onward, his films feature ruined exteriors, shabby interiors, elaborate chiaroscuro, rhythmic camera movement, and very long takes. (Damnation has an ASL of 2 minutes; Sátántangó, 2 minutes 33 seconds; Werckmeister Harmonies, 3 minutes 48 seconds).

Tarr insisted in conversation with me that there isn’t a sharp break between early and late styles. For one thing, his video piece Macbeth (1982) consists of only two shots across 63 minutes. It was made before The Prefab People, so his shift toward the ambulatory long take was already in the works. Moreover, The Outsider ends with a strained restaurant encounter captured in a virtuoso handheld shot running nearly seven minutes. A nightclub scene in The Prefab People likewise features some sidewinding long takes around a dance floor that wouldn’t be out of place, at least in their repetitive geometry, in Damnation.

If we’re inclined to look for other continuities, we can find them. In the films from Damnation onward, the deferred reverse shot has been put at the service of attached point of view, so that often when Tarr’s protagonists peer around a corner or out of a window, instead of optical pov cutting we have an over-the-shoulder view that conceals their facial reaction. One scene in Damnation starts as a typically Tarrian scrutiny of texture, with the wrinkling wall echoing Karrer’s topcoat. But then the camera arcs and refocuses, showing what Karrer is watching but not how he responds.

The blocklike construction of scenes in the early films carries on in the later work, but now Tarr minimizes the cuts within a scene, so that it becomes an even more massive hunk of space and time. Tarr refuses as well to use crosscutting, which would show us various characters pursuing their activities at roughly the same time—another strategy that keeps us fastened to one relentlessly unfolding chain of actions and, usually, one character’s range of knowledge. The avoidance of crosscutting will have major structural implications in Sátántangó, which overlaps characters’ individual points of view by replaying certain events and stretches of time.

The long-held facial shots of the early films don’t create a natural arc; the shot will go on as long as the character wants to talk. Similarly, many long takes in the later films don’t present a beginning-middle-end structure. We simply follow a character walking toward or away from us, pushing into a stretch of time whose end isn’t signaled in any way. This becomes especially clear in those extended long shots in which a character walks away toward the horizon and the camera stays put. Traditionally, that signals an end to the scene, but Tarr holds the image, forcing us to watch the character shrink in the distance, until you think that you’ll be waiting forever. Likewise, the diabolical dance shots of Sátántangó, built on a wheezing accordion melody that seems to loop endlessly, are exhausting because no visual rhetoric, such as a track in or out, signals how and when they might conclude. Early and late, Tarr won’t hold out the promise of a visual climax to the shot, as Angelopoulos does; time need not have a stop.

Nonetheless, I do agree with my fellow panelists that the later films have a significantly different look and feel, and it’s on them that Tarr’s place in world film history will chiefly rest. As I indicated at the end of Figures Traced in Light, he stands out as a distinctive creator in a contemporary tradition of ensemble staging. Like Tarkovsky, he shifts our attention from human action toward the touch and smells of the physical world. Like Antonioni and Angelopoulos, he employs “dead time” and landscapes to create a palpable sense of duration and distance. Like Sokurov in Whispering Pages (1993), he takes us into an eerie, Dostoevskian realm where characters are cruel, possessed, mesmerized, humiliated, and prey to false prophets.

Ties to tradition

Tarr, however, maintains that his work, early or late, owes little to cinema. He claims not to have been influenced by other directors, and he asserts that he gets his ideas from life, not from films. When pressed, he admits that he knew the films of Miklós Jancsó “and I liked them very much. But I think what he does is absolutely different from what we do.”

It’s not uncommon for strong creators to reject the idea of influence, and many feel that they may sap their originality if they’re exposed to other work. Still, nothing comes from nothing. Any artwork is linked to others through an expanding network of affinity and obligation. Often influence is like influenza; you catch it unawares, despite your efforts to ward it off. And sometimes artists on their own find strategies that other artists have already or simultaneously hit upon.

Whether or not Tarr consciously joined a tradition, his practices do link him to several trends. Tarr has rejected the idea, floated by Jonathan, that his early films are indebted to Cassavetes, but there seems little doubt that by 1979, when Family Nest was released, it contributed to the fictional-vérité tradition, regardless of his intent. Likewise, his late films’ reliance on long takes is part of a broader tendency in European cinema after World War II. The neorealists taught us that you could make a film about a character walking through a city (The Bicycle Thieves, Germany Year Zero), and other directors, such as Resnais in the second half of Hiroshima mon Amour, developed this device. With Antonioni, Dwight Macdonald noted, “the talkies became the walkies.” Jancsó took Antonioni further (acknowledging the influence) in the endless striding and circling figures of The Round-Up, Silence and Cry, and The Red and the White. So even if there wasn’t any direct influence, Antonioni and Jancsó paved the way for Tarr; they made such walkathons as Sátántangó and Werckmeister thinkable as legitimate cinema.

Still more broadly, as Hollywood cinema has become faster-paced, accelerating its action and cutting, art cinema in Asia and Europe has tended toward ever slower rhythms. Visit any festival today, as Scott mentioned in our panel, and you’ll see plenty of films with long takes and fairly static staging. I criticize this fashion a bit in Figures, but it’s undeniably a major option on today’s menu. It’s even been picked up in contemporary American indies, with Gus Van Sant’s work from Elephant on offering prominent examples. He, of course, has been crucially influenced by Tarr, but Hou, Tsai Ming-liang, Sokurov, and other directors haven’t. We seem to have a case of stylistic convergence, with Tarr choosing to explore the long take at the same time others were doing so.

Within recent Hungarian cinema, it would be fruitful to examine Tarr’s relation to his contemporaries. Janós Szasz’s Woyzeck (1994) takes place in a wasteland not unlike those of Damnation and Sátántangó. Even closer to Tarr is the work of György Fehér. I’ve seen only Passion (1998; right) and one scene from Twilight (1990). Here again we get very long takes with a supple camera, grungy settings, and down-at-heel characters wandering in rain and mist or dancing as if possessed by demons. Fehér has worked with Tarr as producer, dialogue writer, and “consultant.” We could also explore Tarr and Fehér’s affinities with Benedek Flieghauf, the younger director of The Forest (2003) and Dealer (2004). Fleghauf builds these films around extensive long takes, and the remarkable Forest carries the idea of the suppressed reverse-shot to an eerie extreme, as characters study mysterious offscreen objects that may never be shown us.

Within recent Hungarian cinema, it would be fruitful to examine Tarr’s relation to his contemporaries. Janós Szasz’s Woyzeck (1994) takes place in a wasteland not unlike those of Damnation and Sátántangó. Even closer to Tarr is the work of György Fehér. I’ve seen only Passion (1998; right) and one scene from Twilight (1990). Here again we get very long takes with a supple camera, grungy settings, and down-at-heel characters wandering in rain and mist or dancing as if possessed by demons. Fehér has worked with Tarr as producer, dialogue writer, and “consultant.” We could also explore Tarr and Fehér’s affinities with Benedek Flieghauf, the younger director of The Forest (2003) and Dealer (2004). Fleghauf builds these films around extensive long takes, and the remarkable Forest carries the idea of the suppressed reverse-shot to an eerie extreme, as characters study mysterious offscreen objects that may never be shown us.

More generally, and more speculatively, we could look to a wider movement in late and post-Soviet art toward mournfulness and lamentation in response to cultural collapse. Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia is one instance, but Larissa Shepitko’s The Ascent (1976) and Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985) point in this direction too. Vitaly Kanevsky’s Freeze, Die, Come to Life! (1989) offers a rusting, dilapidated world not far from Tarr’s. In the 1970s and 1980s, composers like Arvo Pärt, Henryk Górecki, Giya Kancheli, Vyacheslav Artyomov, and Valentin Silvestrov created austere, threnodic music that sometimes evokes spirituality but just as often suggests a bleak end to everything. The very titles—Symphony of Sorrowful Songs (Górecki), Symphony of Elegies (Artyomov), Postludium (Silvestrov)—evoke something more than the death rattle of Communism. The pieces can be heard as meditations on the ruins of modern history, asking what humankind has accomplished and what can come next. Tarr’s severe parables, grotesque and sarcastic in the manner of Kafka, don’t exude the religiosity we can find in some of this music or filmmaking, but, at least for me, they share the impulse to lament humans’ inability to transcend their brutish ways. “I just think about the quality of human life,” he remarks, “and when I say ‘shit’ I think I’m very close to it.”

I have more ideas about Tarr, especially on Sátántangó and Werckmeister, but I have to stop somewhere. I hope to see his new film The Man from London when I go to the Vancouver International Film Festival next week, and of course I’ll report on it here.

The best piece of writing I know on Tarr’s cinema is András Bálint Kovács’ “The World According to Tarr,” in the catalogue Béla Tarr (Budapest: Filmunio, 2001).

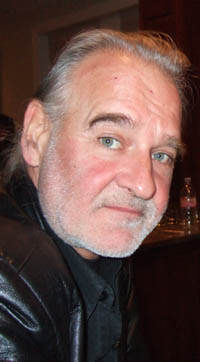

Béla mesmerizes Lola, Chicago 15 September 2007.

Thanks to Milos Stehlik, Susan Doll, Charles Coleman, and Megan Rafferty of Facets, to Béla Tarr for generous conversation, and to András Kovács for enlightening discussions over the years.

PS 20 September: The reports of Tarr’s earlier visit to Minneapolis are emerging; here’s a good link.