Archive for November 2007

Sleeves

DB here:

Earlier this month, when I was giving a lecture on Mizoguchi Kenji at our university museum, I showed two images from A Woman of Rumor (Uwasa no onna, 1954). It’s a little-known film of his, and it’s probably not up to his finest, but seeing the stills again on the big screen made me want to write about one scene. That scene displays aspects of Mizoguchi’s artistry that I touch on in one chapter of Figures Traced in Light and in the website supplement here.

This blog entry constitutes, I suppose, another supplement. After all, I couldn’t include in the book all the moments in Mizoguchi’s work that I find fascinating. But since comparison is a good way to get under a movie’s skin, my examination of a parallel scene from another movie may have more general interest. Even though Woman of Rumor doesn’t seem to be available on video, maybe looking at this pair of examples would inspire some readers to take an interest in one of the two or three greatest filmmakers who ever lived.

In the court of Regina

William Wyler and John Barrymore.

What a year 1941 was in the American cinema! We remember it for Citizen Kane but it also brought us How Green Was My Valley (a better film than Kane, I think), and items like Sergeant York (the biggest box-office hit), Dumbo, The Philadelphia Story, Suspicion, Ball of Fire, High Sierra, The Lady Eve, Meet John Doe, The Maltese Falcon, They Died with Their Boots On, and one of the most daring movies ever made in America, The Little Foxes.

An adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s play, The Little Foxes offers a study in unbridled capitalism. It shows how economic interests pit the South against the North and white against black. Psychologically, it analyzes a household gripped by the ruthless domination of the matriarch Regina (Bette Davis), the wiliest member of a family of grasping entrepreneurs. Regina has all but flattened her husband and is trying to make her daughter Alexandra oblivious to the family’s corruption.

The Little Foxes was also bold in its style—in its own way, as venturesome as Citizen Kane. It hasn’t been fully appreciated because Wyler is still thought of as a rather middlebrow talent, an overcautious director who toned down the flamboyance of Gregg Toland’s deep-space and deep-focus compositions.

Some day I hope to blog in defense of Wyler, middlebrow movies, and Midcult art in general. That would involve a detailed analysis of Little Foxes. (1) For now let’s just say that Wyler’s direction of the film won the admiration of no less than André Bazin. Bazin taught us to appreciate Wyler’s work, though with some prompting from Wyler and Toland (as I suggest here). Wyler was also appreciated by Mizoguchi, who, apparently grudgingly, told his screenwriter Yoda that he admired Wyler’s use of the “vertical frame.” (2) Later I’ll suggest one way of understanding that phrase. Mizoguchi met Wyler at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, when Ugetsu Monogatari was up against Wyler’s Roman Holiday for the Silver Lion.

One scene not discussed by Bazin or Mizoguchi, as far as I’m aware, has always gripped me. Regina’s brother Oscar has a wife, Birdie, who has turned into a passive alcoholic. Birdie has learned of plans to marry Xan off to Leo, her shallow son. Her will has been broken by Regina and Oscar, but she summons up the courage to blurt out to Xan that she mustn’t marry Leo, no matter how strongly the family insists. Xan, who has no inkling of how her family twists people to suit their ends, protests that no such thing could happen. But Oscar overhears Birdie warning Xan off.

Birdie and Oscar are about to leave at the end of the evening. Wyler begins with a standard two-shot, very slightly off-center. But as Birdie frantically warns Xan, Oscar’s sleeve and pant leg appear in the lower left of the frame, with the swagged curtain at the doorway hiding his face.

For us, this creates suspense. Only after Birdie has babbled out her warning do the two women notice he’s there. Xan, not knowing how Oscar abuses Birdie, heads off to bed.

As she climbs the staircase (very important in the film and the original play, this staircase) and heads off to her bedroom, Wyler’s camera arcs to reveal Oscar. Wyler now cuts to show, more or less from Birdie’s point of view, Xan going into her room.

Birdie watches anxiously, then turns to face Oscar, with a look of resigned apprehension.

Again suspense: Oscar won’t punish Birdie with Xan watching, but the girl’s departure puts Birdie in jeopardy. In addition, Wyler’s shot of her reaction anticipates the wrath she’ll face. (Patricia Collinge’s fluent performance is equal to the dynamics of Wyler’s visuals.) These cuts anchor our empathy; Wyler has been saving the close-up of Birdie for this moment.

We return to the master framing as Birdie heads toward Oscar, passing into a patch of shadow. As she does so, he raises his hand abruptly.

Wyler cuts to a two-shot. Oscar slaps Birdie so hard she seems to bounce against the left frame edge. She cries out and then tries to stifle her voice—a psychologically apt gesture for this woman who muffles her sorrows throughout the film.

Again, Wyler daringly sets a key action off-center. The brutal discontinuity of the cut, which crosses the axis of action and sharply changes shot scale, accentuates Oscar’s violence. It’s also rather elliptical; run the cut slowly, and you never see his hand strike her.

Xan hurries out of her room and comes to the banister, her face on the upper right balancing the placement of Birdie’s in the prior shot. In the next shot, we see, over her shoulder, Oscar stride out. Birdie follows meekly, assuring Xan that nothing’s wrong. The coda of the scene will emphasize Xan’s puzzled anxiety, a phase in her process of coming to understand the domineering fury that rules her family.

Low- and high-angle shots like this last pair recur throughout The Little Foxes, and I suspect that these are the sorts of thing Mizoguchi was invoking in mentioning Wyler’s “vertical” space. Wyler’s steep angles activate upper areas of the frame that many American directors hadn’t explored.

The act of overhearing a revealing conversation is a standard dramatic convention, but Wyler has refreshed and nuanced it. We know how it would be normally handled. We’d see either a shot showing Oscar stepping fully into the background, or a series of cuts showing first Birdie and Xan and then Oscar listening and watching. Wyler revises the standard schema, taking it for granted that we can pick up on a subtler cue than usual: just a bit of Oscar’s body intrudes.

As a result we have to be more alert. The information isn’t centered, but rather tucked into the lower left. And this option conceals Oscar’s face. Not that we’re doubting he’s angry, but delaying showing his anger builds up greater tension. Wyler, unlike today’s directors, knows when to build up to revealing things that we anticipate, making the final outburst more forceful when it comes. Further, the rest of the scene continues to deny us a clear view of Oscar’s anger, all of which gets squeezed into his gesture of slapping Birdie. It’s Birdie’s reaction that Wyler stresses, and Oscar’s contempt for her is conveyed simply by his bearing, his gesture, and his manner of stalking out of the foyer.

It’s not too much to talk about rigor here. The schemas dominating today’s filmmaking, the stylistic paradigm I call intensified continuity, would demand tight close-ups of everybody from the start. But providing them would make it harder for Wyler to raise the emotion when the startling slap comes. Maybe a contemporary director would render this spike in slo-mo, or with a wobbly handheld camera, but that tends to seem overbearing and pumped-up—as a lot of current stylistic pyrotechnics do. In any case, I’m betting that no American director today would use Oscar’s sleeve in the quietly ominous way Wyler does.

Mizoguchi’s game of vision

Mizoguchi Kenji, in glasses, during the making of Ugetsu.

Mizoguchi is renowned for his long takes, which are often sustained in distant views featuring considerable camera movement. In the Mizo chapter in Figures Traced in Light, I suggest that these stylistic choices spring from his effort to engage the viewer mesmerically—as he put it, “to work the viewer’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.” He asks us to downshift our attention to the finest details of the action, which he then modulates for expressive effect. I draw examples from various films across his career to show how he creates drama out of remarkably slight differences in character position, lighting, and other factors.

But what happens when he foreswears virtuoso camera movements and single-take scenes and breaks the drama up into several shots? Today, many ambitious directors seem to take pride in stretching out their takes, so cinephiles are sometimes inclined to see a cut as a loss of nerve and a concession to the audience. But I try to show in Figures that Mizoguchi sustains his concern for nuance when he creates an edited sequence. The modulation of fleeting details is to be found in his closer shots too.

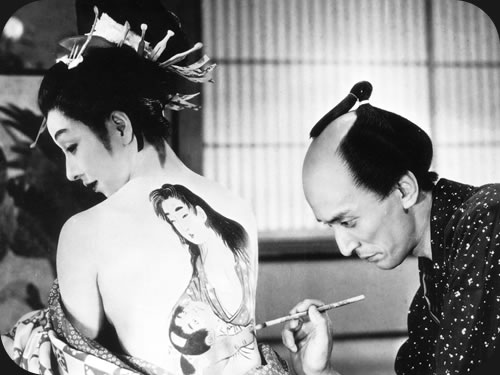

In A Woman of Rumor, Hatsuko runs a teahouse that funnels customers to the geisha establishment behind it. She has tried to protect her daughter Yukiko from the shame of her profession. Hatsuko has also been cultivating a young doctor she hopes to marry, giving him money to set up a clinic. Now the doctor, Matoba, has become attracted to Yukiko. The scene I’m examining takes place during the performance of a noh drama. Hatsuko leaves the auditorium and finds Yukiko talking with Dr. Matoba.

As she passes around a screen, she hears Yukiko saying she wants to learn piano in Tokyo. Hatsuko looks left, and Mizoguchi cuts to an approximation of her optical point of view on the couple in the lounge.

So far, so conventional. Mizoguchi seems to follow the intercutting option for treating a scene of overheard conversation. But he goes further. Having laid out the action, Mizoguchi starts the lesson in just-noticeable-details . . . with a sleeve. He cuts to a reverse shot putting Matoba and Yukiko in the foreground. Hatsuko is still back there, though. We can see her kimono sleeve on the left, poking out from behind the screen.

A sharp-eyed viewer might also spot Hatsuko’s shadow on a wall, in the center of the shot, over Matoba’s shoulder. This blow-up shows both the sleeve and her silhouette.

Here, friends, is one reason we want to watch films in 35mm, and projected really big.

It’s now that Yukiko says that she may leave her mother, and Matoba replies, “Maybe I’ll go too.” This is devastating to Hatsuko. The two people whom she loves most seem to care nothing for her. Her shocked reaction is given in a medium-shot showing her shifting out from behind the screen, her face partially hidden.

Mizoguchi has picked one variant of the overheard-conversation schema: shot of speakers/ reaction shot of eavesdropper. But he’s done so in his own way, using the barely discernible kimono sleeve to signal Hatsuko’s presence in the full shot of the couple. Likewise, the shot of Hatsuko listening is far from the usual close-up. Like other Japanese directors, Mizoguchi was fond of this arresting single-eye image. He used it earlier in his career, as shown in the first frame at the top of this entry, from Hometown (Furusato, 1930). The second frame is the last shot of his last film, Street of Shame (Akasen chitai, 1956). Quite a shot to end your career on, I’d say.

Most Japanese directors use this single-eye framing as a one-off flourish, but not Mizoguchi. The device epitomizes his demand that we concentrate on a detail. Isolating half a face gives impact to the slightest shift in the eye and eyebrow. Moreover, the split face reappears as a pictorial motif later in the scene.

As Matoba says he’ll go back to Tokyo for his doctorate, Mizoguchi cuts back to the setup for the second shot. Hatsuko moves left to sit on a chair around the corner from the sofa. This prepares for another, more prolonged game of visibility.

Now we get a thirty-second take of the couple on the sofa. As the scene develops, it becomes evident that Matoba is seducing Yukiko. Hatsuko slips in and out of visibility, her actions responding to and even echoing Matoba’s pressure on the girl. First, as he talks with Yukiko, we see Hatsuko’s sleeve and shoulder, between the vase and his shoulder. But as he slips his arm around Yukiko, her elbow moves aside, in an echo of his gesture.

Then, when Matoba presses his attention (“We’ll help each other . . . Depend on me”), Hatsuko’s face pops into view as her fingers emerge to grip the edge of her chair. Mizoguchi then lets her face subside, again slicing it in half.

In effect, this shot replays and expands upon the tactic governing the earlier two shots. Again we get the just-noticeable presence of the sleeve, but now rhyming with the action in the foreground. And again we get the facial reaction, impeded by a vertical cutoff, but this time in the distant shot rather than in a closer view. It turns out that those first four shots were training us for this more intricate game of vision.

At the moment Hatsuko’s face is sliced in half, Mizoguchi cuts. Now he prolongs the close view as he had extended the full shot of the couple. In this thirty-second shot, we watch her reaction, played out in slight modulations—changes in her facial expression, changes in the aspect of her face that we see, and changing relations to the curling palm plant in the vase before her.

We get a new angle on Hatsuko, slightly high, as Matoba says, “I’ll tell her.” Hatsuko stands up abruptly and the camera tilts to follow her.

With the simple action of her rising up, Mizoguchi changes his composition sharply. Hatsuko’s position in the frame changes only a little bit, but the massive vase on the left gives way to the curling stalks on the right. Radically refreshing a shot through minimal means is one felicity of Mizoguchi’s art.

Then, as if the full import of Matoba’s betrayal dawns on her, Hatsuko lowers her head sadly. Again her eyes are split up, this time thanks to the twisting stalk. In a characteristic Mizoguchi gesture, she turns from the camera, as if ashamed to face us, but also summoning up reserves for the next emotional shift.

When she turns back, her face burns.

I take this to be the scene’s emotional climax. Mizoguchi could have given it to us much sooner, by having Hatsuko turn angry as she peeped out from behind the screen. Instead, his game of vision allowed him to build patiently toward this unimpeded shot of her reaction. It prepares us for the next stages of the drama, later scenes in which she will confront her patron and launch jealous accusations at Yukiko.

Now we hear the performance ending, and Hatsuko lifts her head. This phase of the scene ends when Mizoguchi cuts to audience members coming into the lounge and greeting her.

By 1954 Mizoguchi had surely seen The Little Foxes. Had he decided to redo Wyler’s virtuoso staging in his own manner?

Both directors work with similar ingredients: overheard conversation, depth shots, judicious close-ups, and partial views. But the narrational weightings differ. Wyler’s film aligns and allies us with the people talking, whereas A Woman of Rumor ties us to the listener. (3) Wyler’s eight shots take eighty-one seconds; Mizoguchi’s eight shots take about two minutes.

Wyler’s handling is brisk, tense, and remarkably nuanced within the Hollywood tradition. Mizoguchi gives us his scene more sedately, wringing just-noticeable differences out of unassertive performances and simple elements of setting. No slap here, just a drama of wounded pride, lost love, and jealousy played out in the face, back, and sleeve of Tanaka Kinuyo, shifting behind a floral arrangement. What Wyler gives us as one sharp effect, Mizoguchi turns into a delicate, prolonged game of vision.

Am I fussing over minutiae? No; Wyler and Mizoguchi did. We just have to follow where they lead. As I try to show in my essay on blinking in cinema (4), directors attend closely to things that might seem trivial. Our analysis needs to be as fine-grained as their craft and artistry.

Oh, yes: at Venice Ugetsu won the Silver Lion. Wyler had to be content with Roman Holiday’s three Academy Awards.

(1) I sketch some of the possibilities in On the History of Film Style (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 225-227.

(2) For more on Mizoguchi’s competition with Wyler, see Figures Traced in Light (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 134.

(3) I’m referring to Murray Smith’s deft analysis of what he calls alignment and allegiance in our relation to film characters. See Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion, and the Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), Chapters 5 and 6.

(4) “Who Blinked First?” in Poetics of Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2007), 327-335.

PS 3 December: Thanks to Michael Kerpan for a name correction, and for the information that Woman of Rumor was once available on a French DVD.

PPS 27 February 2008: Good news. Now Woman of Rumor is available on the wonderful Eureka! Masters of Cinema series, along with the superb Chikamatsu Monogatari. The discs come with voice-over commentary by Tony Rayns and essays by Keiko McDonald and Mark LeFanu.

Bob Shaye is the most reckless man in Hollywood. True or false?

|

=

? |

|

Kristin here–

As a writer and even more as a reader, I am frequently baffled when an author with a fascinating, innately dramatic story to tell feels it necessary to ratchet up its appeal with hype. I’m an amateur Egyptologist and sometimes watch the documentaries made by the Discovery Channel, National Geographic, and the other educational TV outlets. Now, a great many people are fascinated by ancient Egypt in a way that they aren’t by virtually any other period of history. So many events and aspects of that society are at least intriguing, at most amazing. The building of the pyramids, the process of mummification, the distinctive artworks–all of these could sustain straightforward presentation.

Instead, the filmmakers responsible for these documentaries feel it necessary to beef up their ancient subject matter. The factual scenes are interspersed with shots of actors dressed in pharaonic costumes driving chariots across the desert, accompanied by overblown music. Archaeologists hover outside supposedly sealed tombs or chambers, speculating breathlessly as to what might be inside. Artificial mysteries are overly prolonged, when all along the filmmakers know the answers. Since the channels producing these documentaries are often subsidizing the archaeologists’ work, there is pressure for these scholars to make more glorious claims for their findings than the facts warrant.

Similarly, film history contains innumerable stories that are both educational and entertaining, if told in a straightforward, factual way. Any major film’s making yields many facts and anecdotes that are in themselves interesting. Yet here, too, many authors—especially journalistic ones—seem to feel the need to inject an artificial drama into their tale. This can be harmless, but if an author tries too hard, the facts get obscured or distorted.

In the case of big box-office successes, journalists tend to find one over-arching claim that can seem to explain a film while giving it an extra dose of drama. There was one such concerning The Lord of the Rings that I encountered over and over when I was researching The Frodo Franchise. Despite all the twists and turns that the progress of the film took—the unlikely move from Miramax to New Line, the last-minute casting of Viggo Mortensen, the struggles to reach remote filming locations, the third part’s winning eleven Oscars, and many, many more—somehow there wasn’t enough drama. In this case, the big claim was that Rings was an immense gamble on the part of New Line’s founder and co-president, Bob Shaye. Some have believed, both before and after the trilogy’s release, that its failure would have meant the end of New Line. The independent firm would have been absorbed into parent company Time Warner, and Shaye would have been stripped of power.

My book was written after all three parts of Rings had gone into the box-office record books. New Line had grown considerably and was in no danger. During my research I questioned people involved in the film’s production and people in the industry who would have reason to know whether New Line really stood in such a precarious position in 2001. Opinions were divided, but few thought that New Line would have disappeared had the trilogy flopped. A gamble, yes, but ones where the stakes were lower and the odds more in New Line’s favor than most accounts would suggest.

Boffo! by Bart

I can see why journalists, even in trade papers like Variety and Hollywood Reporter, would find it convenient to fall back on this gamble motif when writing copy on a short deadline. Now, however, the familiar claim has reappeared in Peter Bart’s book, Boffo! How I Learned to Love the Blockbuster and Fear the Bomb (Miramax Books, 2006). Bart deals with extremely successful films, plays, and TV shows. The Lord of the Rings occupies one chapter.

When the first anniversary of this blog rolled around, David wrote about some of our goals as film scholars and bloggers. One of them was this:

We’ve tried to deflate some clichés of mainstream film journalism. Writers of feature articles are pressed to hit deadlines and fill column inches, so they sometimes reiterate ideas that don’t rest on much evidence. Again and again we hear that sequels are crowding out quality films, action movies are terrible, people are no longer going to the movies, the industry is falling on hard times, audiences want escape, New Media are killing traditional media, indie films are worthwhile because they’re edgy, some day all movies will be available on the Internet, and so on. Too many writers fall back on received wisdom. If the coverage of film in the popular press is ever to be as solid as, say, science journalism or even the best arts journalism, writers have to be pushed to think more originally and skeptically.

The same goes, only more so, for books written in the same spirit. Journalistic writing is at least somewhat ephemeral. Books, though, stay on the shelf, and they automatically command a certain respect.

As I said, the story of Rings, told straightforwardly, is immensely dramatic. What better story could a film historian possibly have to tell? All through the researching and writing processes, I tried simply to discover, convey, and interpret that story without adding hype.

Bart adds the hype. His chapter on Rings not only revives the old gamble angle but goes further, asking, “What was the bravest gamble in the history of filmmaking?” Arguably, he answers, the trilogy.

Why? First, it was risky to make all three films at once. Granted, though as Bart acknowledges, there were enormous cost benefits from doing so. Second, the initial budget of $130 million, according to Bart, ballooned to $330 million. Now the problems start. $130 million was the budget when Rings was still a two-part project at Miramax. Taking over the film, New Line provisionally kept the existing budget until a three-part script could be written and the costs estimated on a firm basis. The estimate then grew to $270 million, which we should count as the budget the studio was really working from. The success of Fellowship of the Ring led New Line to agree to requests for more money in making the second and third parts. Costs did not run wildly over expectations.

What else was so risky? According to Bart, New Line earmarked “virtually its entire production budget to support the effort.” If Bart has evidence for this claim, he doesn’t share it. Without access to New Line’s accounts, we can’t be absolutely certain. Still, there is considerable evidence to the contrary. New Line executives have consistently pointed out that, spread over the three years of the trilogy’s release, their own annual investment was relatively small. Co-president Michael Lynne has said in a number of interviews that most of the budget was covered by other companies. In a recent issue of Screen International, he declared, “The foreign distribution rights alone were responsible for close to 70%” (Mike Goodridge, “The Ringleaders,” October 26, 2007, p. 23).

There were 26 foreign distributors, several of whom paid visits to the Wellington facilities during the production. I have talked with some of the filmmakers who took those distributors on tours. My book includes a case study of the Danish distribution company based on a two-hour interview with one of its executives (Chapter 9). During the years of the trilogy’s release, the trade journals, including Variety, ran stories about these distributors. The 70% figure, by the way, doesn’t count the merchandising licenses, many of which had been sold in 2000, helping to finance the trilogy. New Line was gambling, but largely with other people’s money.

Further, Bart declares, Shaye’s decision was a gamble because the narrative of Tolkien’s novel was so complex that it had previously scared off Spielberg, Kubrick, Harvey Weinstein, Saul Zaentz, and the Beatles (p. 51). Again, my research points in other directions. I have never heard that Spielberg was in the running to make Rings at any point. Stanley Kubrick was approached by Apple, the Beatles’ company, back in the late 1960s, when the Fab Four were interested in starring in a film adaptation of Rings. I suspect that it wasn’t the novel’s complexity that made Kubrick decline. (The Beatles got interested in transcendental meditation and went off to the Far East.) Bart says that Saul Zaentz “did little” with the production rights once he acquired them (p. 54). But in 1978 Zaentz produced an unsuccessful animated version of the first half of the book and decided not to make the sequel. Harvey Weinstein very much wanted to keep the Rings project at Miramax, but he was forced by parent company Disney’s head, Michael Eisner, to scale it back to a single two-hour feature. Peter Jackson refused to accept that condition and took the project to New Line.

Finally, Bart points out that Jackson was then a little-known director with not a hit to his name. True, but as I point out in my book, for the short time the Rings was in turnaround from Miramax, Jackson alone had the power to bring the project to New Line. Shaye undoubtedly wanted the rights to Rings, believing that it would make a successful franchise. Jackson came along with those rights.

Late in the chapter, Bart offers another reason why taking on the trilogy flew in the face of conventional wisdom: New Zealand is very remote from Hollywood (p. 63). Perhaps the distance caused some troubles, but it saved a huge amount of money—enough to make the difference between the trilogy getting made or not. In The Frodo Franchise I calculate (based on costs for a comparable effects-heavy epic, Titanic) that Rings might have cost roughly $544 million if made in North America (or $700 million if one includes the 120 minutes of extended-edition footage). Jackson undertook a similar estimate based on Pearl Harbor and came up with a figure of $180 million for Fellowship—and three times that is $540 million. The difference between those figures and $330 million pays for a lot of airline tickets.

Shaye’s “Gambler” Reputation

One of Bart’s conclusions is, “For those who, like Bob Shaye and Michael Lynne, believed that big returns emanate from big risks, Lord of the Rings provided a unique and generous validation” (pp. 63-64). This is peculiar indeed. I don’t think either Shaye or Lynne would agree with that assessment of their approach to production. Shaye was known for running a tight fiscal ship at New Line. His company became famous for turning miniscule investments into massive hits and franchises: most notably, Nightmare on Elm Street and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Shaye has a sign on his office wall that reads “Prudent Aggression.” That, I would say, is the attitude with which he approached the Rings decision.

Neither Shaye nor Lynne has generally encouraged the notion of the Rings deal as a gamble. (See my first chapter for more on this.) In the Screen International piece cited above, the interviewer asks that very question: “Do you agree that the trilogy was the riskiest venture that any film company has tried to date?” Shaye responds, “We had hedged somewhere between 70%-80% of our investment.” Lynne adds, “If it had broken even, nobody would have been happy. The company wouldn’t have gone out of business, but it definitely would have been a problematic issue for people who had invested with us, and for Time Warner itself.” (The investors were the international distributors who had pre-bought the entire trilogy.)

In an interview on The Charlie Rose Show earlier this year, Lynne said something similar: “The problem was, if the first film didn’t work, the next two were certainly not going to work, that these films would at best break even. Well, no one at Time Warner was going to be thrilled that we invested the three hundred million dollars and just got our money back! So although we weren’t betting the ranch, we certainly were betting our credibility.”

The gambler image no doubt redounds to Shaye’s advantage in some ways. He was the only one in Hollywood willing to take on the immense project when Jackson was shopping it around the studios. He was famously the one who told the director that he should make three films, not two. Despite occasional tensions between the filmmakers and studio executives, Shaye and Lynne not only stuck with the project but acceded to requests for tens of millions in additional spending. Shaye’s resulting image is that of a savvy maverick who outguessed the heads of the other studios.

On the other hand, it can’t be to his advantage to be perceived as reckless. If people think that Rings really was the biggest gamble in the history of Hollywood and that Shaye risked $330 million of his own firm’s money, blithely taking a chance on a director of splatter films, then he risks coming across as irresponsible. Hence, I suspect, his and Lynne’s care in informing interviewers that they had found investors and licensees to cover the bulk of the trilogy’s budget. Shaye has also pointed out that the trilogy stretched over three fiscal years, as I mentioned, making the annual investment in Jackson’s film modest relative to its epic qualities.

Of course the trilogy was a gamble. As Shaye said in the Charlie Rose interview, “But every film commitment is a gamble to some extent.” The size of this particular gamble, however, has been considerably exaggerated. Shaye and Lynne knew what they were doing. They saw the savings to be had by filming in New Zealand and by committing the cast members up front to all three films—hence obviating the possibility of ballooning salary demands if the first part was successful.

I’m sure there were many moments of worry and doubt in the years between New Line’s official announcement of the project on August 24, 1998 and the triumphant preview screenings at Cannes in May, 2001—when journalists and foreign distributors alike realized that the studio had, as Harvey Weinstein put it at the time, “another ‘Star Wars’ on their hands.” Still, I would place a small bet that during those same years the disastrous Town & Country (filmed in 1998 and released in late April, 2001) was giving Shaye and Lynne at least as much anxiety. That long-delayed film cost $90 million, with a publicity budget of $15 million. It grossed $10 million worldwide.

Above all, Shaye saw the likelihood of the trilogy’s success in a way that no one else did. My favorite statement of his was quoted in a Time article in late 2002, shortly before the release of The Two Towers. Asked why he had wanted three films instead of two, Shaye replied: “It was so wonderfully presold. It was like Superman or Batman.” Juxtaposing Tolkien’s novel with those comic-book superheroes might bring a smile—but he was right. If we can just set aside the persistent notion that Rings was a huge gamble, we can see that Shaye was remarkable for his foresight, not his recklessness.

The adolescent window

DB here:

Last month I visited the University of Texas at Austin. I had a great time, with wonderful people and conversation. The food was tasty too. There was a lot of talk, and one question in particular set me thinking.

In his Film History seminar, Professor Charles Ramirez Berg asked me what movie made me decide to study film. Before I knew what I was saying, I admitted that unlike most people who write about movies, no single movie, nor even a handful of movies, pushed me in this direction. I had no cinematic epiphany.

Nor did I have the sort of childhood that seems archetypal for film geeks. You know the tale. I grew up in New York/ Chicago/ LA and went to the movies every day, sometimes twice or more. I practically lived at the [insert colorful but rundown movie house here]. When I wasn’t at the movies I was watching little-known film noirs/ Monograms/ Budd Boettichers on TV into the night. By the time I could vote, I’d seen thousands of movies, and King Kong at least five times.

This wasn’t me. I grew up on a farm. I saw at most one or two movies a week on those Saturday afternoons when my family went to the town ten miles away. I saw what every kid saw—Disney, Martin and Lewis, Francis the Talking Mule. I did sometimes watch Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto movies on the couple of TV channels we could pull in, but I didn’t saturate myself. About age thirteen I started to get interested in film by reading about it, in books like Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art and Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now. These were my guides to what to watch on TV. So yes, I did stay up late occasionally, but to see bona fide classics like Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons. The joys of Joseph H. Lewis and Robert Siodmak had to wait until in 1963 my hands closed around the Film Culture issue devoted to Andrew Sarris’ American Directors survey.

So I became a film wonk through years of accretion, gradually seeing more and more in high school (once I could drive a car) and college (running the film society) and then deciding to go to graduate school.

But I did find an answer to Charles’ question. I said that my childhood was far more steeped in TV and radio than in movies. Afterward I realized that certain books and magazines had a big influence on me as well.

What follows may seem narcissistic nostalgia, but I do have a general point. It’s the Law of the Adolescent Window:

Between the ages of 13 and 18, a window opens for each of us. The cultural pastimes that attract us then, the ones we find ourselves drawn to and even obsessive about, will always have a powerful hold. We may broaden our tastes as we grow out of those years—we should, anyhow—but the sports, hobbies, books, TV, movies, and music that we loved then we will always love.

The corollary is the Law of the Midlife/ Latelife Return:

As we age, and especially after we hit 40, we find it worthwhile to return to the adolescent window. Despite all the changes you’ve undergone, those things are usually as enjoyable as they were then. You may even see more in them than you realized was there. Just as important, you start to realize how the ways you passed your idle hours shaped your view of the world—the way you think and feel, important parts of your very identity.

Let me get specific.

The view from my window

Jean Shepherd. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah.

I was born in 1947 and graduated from high school in 1965. What was my angle of view onto the pop-culture landscape in 1960-1965?

Reading: I read a lot of classic and contemporary American literature, especially Twain and Faulkner. Also a lot of nonfiction, especially Barzun, Orwell, and Kenneth Burke. But more eagerly I soaked up detective stories. Not the hardboiled ones, though I loved Hammett’s Red Harvest. My favorites were Sherlock Holmes, Wilkie Collins, and the Golden Age classics: Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, John Dickson Carr/ Carter Dickson, Ellery Queen, and Rex Stout. I now realize that from these skilful storytellers I was absorbing lessons in narrative construction, as well as a taste for artifice.

More specifically, I was learning something I could only much later make explicit: Popular culture undertakes formal experimentation as intriguing as anything in the official avant-garde. Ellery Queen’s openly fabulist novels take a central motif—a nursery rhyme, a pun, the Ten Commandments—and then show how it informs action, character psychology, even chapter breaks. John Dickson Carr’s books are like conjuring tricks, with the magician brandishing the clues and steering you away from the trap doors and collapsable top hats. Who else but Carr would call a novel The Reader Is Warned? Among the moderns, perhaps only Ed McBain has the Golden Age flair for creating a multilayered plot based on a central image like ice or a wedge, and he does it within the frame of the most purportedly realistic mode, the police procedural.

Or take a book I’ve probably read twenty times, Anthony Berkeley’s The Poisoned Chocolates Case (1929). Six eminent lawyers, writers, and amateur sleuths have formed a club, the Crimes Circle. They’re presented with a current murder case and challenged to crack it. At six nights of Circle meetings, each one fields a solution, only to have it shot down. Sort of a grad seminar in homicide.

Admirers of film noir and the hardboiled school, who are in the majority now, would complain that this is just the sort of airless exercise that turned the detective story into a crossword puzzle. Yet there is tension whenever we play off competing answers to a question; anyone who thinks that empirical reasoning is bloodless should read a scientist’s biography. Out of a handful of clues and three or four suspects, The Poisoned Chocolates Case conjures up six detailed but mutually exclusive solutions. At the end, there’s a purely aesthetic pleasure in watching the puzzle snap into a surprising whole that integrates aspects of all the failed answers. As a cherry on the sundae, we’re rewarded with one of the niftiest last lines in crime fiction: “Nobody enlightened him.”

My tastes in the genre have broadened. Now I read and reread Le Carré, Rendell, Hillerman, Westlake/ Stark, Bloch, and the procedurals, especially Rankin. Of course I like Highsmith and Elmore Leonard. Robert Barnard and Peter Dickinson can sometimes evoke Golden Age knottiness. But when I want formal highjinks, I pack a classic in my carry-on and I’m seldom disappointed.

On the Austin trip it was Stout’s The Rubber Band, an elegant adventure of Archie Goodwin and Nero Wolfe.

I’ve registered my admiration for Stout elsewhere on this blog; I consider him one of the great masters of American vernacular prose. The Rubber Band is one of his best, and not just because every page boasts at least one of Archie’s irresistible sentences about Wolfe.

I’ve registered my admiration for Stout elsewhere on this blog; I consider him one of the great masters of American vernacular prose. The Rubber Band is one of his best, and not just because every page boasts at least one of Archie’s irresistible sentences about Wolfe.

Since he only went outdoors for things like earthquakes and holocausts, he was rarely guilty of movement except when he was up on the roof with Horstmann and the orchids, from nine to eleven in the morning and four to six in the afternoon, and there was no provision there for pole vaulting.

That’s writing.

TV, I now realize, tutored me further in the unbridled audacity of popular culture. Granted, in certain circles I’ve been known to say unenthusiastic things about TV. Nowadays I don’t watch anything but The Simpsons and Keith Olbermann. But who can deny the past? I’m a creature of the box.

My parents got TV early, in the early 1950s, and my sisters and I spent many a winter afternoon in front of cartoons, the Disney show, and Roy Rogers. But I didn’t like the official hits, like Gunsmoke and Bonanza. As I got older, I was snagged by grownup shows like Jackie Cooper’s Hennessey and the short-lived It’s a Man’s World. Why? I don’t know. Perhaps they showed how badinage could mingle with serious drama. No mystery about Ernie Kovacs, though, whose nuttiness delighted me in the way that Monty Python would capture the kids of the 1970s. And like everybody else, I was haunted by a weekly visit to the Twilight Zone.

But above all stood George and Gracie. When I started to get what they were about, their program was ripening into its baroque phase. More than individual shows, I remember the brilliant central conceit. Gracie would hatch a wacko scheme, usually recruiting the hapless Harry von Zell as her minion. George would get suspicious and retire to his den to tune in the very show we were watching. He was then in a position to block her maneuvers, usually by tormenting von Zell. The idea that George could simply watch his own program still seems a stroke of genius. Artistic form, I must have realized subconsciously, can always be turned into a dizzy game. M. Godard, Ozu-san, meet Burns and Allen.

But above all stood George and Gracie. When I started to get what they were about, their program was ripening into its baroque phase. More than individual shows, I remember the brilliant central conceit. Gracie would hatch a wacko scheme, usually recruiting the hapless Harry von Zell as her minion. George would get suspicious and retire to his den to tune in the very show we were watching. He was then in a position to block her maneuvers, usually by tormenting von Zell. The idea that George could simply watch his own program still seems a stroke of genius. Artistic form, I must have realized subconsciously, can always be turned into a dizzy game. M. Godard, Ozu-san, meet Burns and Allen.

The radio was constantly on in our house, with my mother listening to Arthur Godfrey or Art Linkletter. These geezers were intolerable to my teenage tastes. Give me my two main sources of aural pleasure: WKBW radio and Jean Shepherd.

WKBW was a radio station out of Buffalo. At 50,000 watts it was so powerful it tended to seep into any blank spot on the dial. Actually, the DJs probably didn’t need an antenna, since they conducted their shows at ear-splitting volume. They indulged in all the profound things that characterized radio in the 1950s: cute sound effects (car crashes, always good), music clips (audio tape made it easy), jingles and station IDs that quickly became earworms, and nonstop patter sustained by whinnies, table-pounding, and laughter at feeble jokes. KB’s promotional efforts were no less strenuous. Once the station asked the public’s help in finding a missing DJ, only to reveal that he’d gone into hiding to drum up publicity.

WKBW was a radio station out of Buffalo. At 50,000 watts it was so powerful it tended to seep into any blank spot on the dial. Actually, the DJs probably didn’t need an antenna, since they conducted their shows at ear-splitting volume. They indulged in all the profound things that characterized radio in the 1950s: cute sound effects (car crashes, always good), music clips (audio tape made it easy), jingles and station IDs that quickly became earworms, and nonstop patter sustained by whinnies, table-pounding, and laughter at feeble jokes. KB’s promotional efforts were no less strenuous. Once the station asked the public’s help in finding a missing DJ, only to reveal that he’d gone into hiding to drum up publicity.

In my day, the loudest mouth belonged to Joey Reynolds, who brayed over records and satirized rock and roll with an appalling ditty called “Rats in My Room.” When he was fired, he nailed his shoes to his boss’s door, adding a note: “Fill These.” I was happy to learn that this piece of teenage lore seems to be true, or at least so a fanatical WKBW website indicates. Joey continues on the airwaves, albeit more sedately.

Speaking of music, KB opened the adolescent window to the tunes that still move me. I was too young to like Elvis and had an affectionate but distant relation to the Beatles. My favorites came mostly from what I’ve learned to call the Brill Building sound. On 24 December every year, Kristin folds her arms in weary patience as the Drifters, Gene Pitney, Connie Francis, and Paul Anka pour forth into our living room.

Jean Shepherd was a wholly different story. The WOR signal couldn’t creep into upstate New York by day, so my bedside tube radio crackled and hissed as 11:15 p. m. approached. Would the signal pull through? It usually did. In fact it seemed to get stronger as, lying in the dark, I heard the familiar trumpet call and galloping music that announced Shep’s show. Another difference from Top 40: Here was an adult talking to a kid as if I were an adult. And an adult who lived in Manhattan! I discovered then that the media aim downward, age-wise: a teenage TV show is actually watched by pre-teens, a college show (like Shep’s) appeals most to highschoolers (like me).

Shep was one of the pioneers of long-form talk radio. He didn’t take phone calls and he seldom had guests. He claimed to be a social commentator, and he did point out the foibles of contemporary media and society. Mostly, though, he was a yarn spinner in the Twain tradition. As he told stories from his life, especially his childhood in Indiana, digressions would split off unexpectedly. Somehow, though, everything wound back to make a point–usually about the vainglory of being human. What made the stories fascinating was not only the delivery (poetic turns of phrase, a smooth, earnest voice that could sink to an urgent whisper) but their fundamental ordinariness. He told of midwestern air shows, enamel table tops, summer baseball, and disastrous Valentine’s Day parties. He celebrated the commonplace and advised his listeners to simply watch everything closely, to find the poetry and absurdity that pervade our lives. I think that my sense of humor owes a lot to him. Perhaps also my tendency to yakkiness.

Shepherd is best-known today for A Christmas Story, the movie based on some of his stories. If you’ve seen it, you’ve heard his unique voice as the narrator. But I first heard the tales of the BB gun and the Old Man’s fetishistic leg-lamp while hunched under the blankets, long after my family had gone to sleep, and Shep’s words put a movie in my head. After my nightly WOR adventures, Garrison Keillor seemed labored and condescending.

From Eugene Bergmann’s capacious book on Shepherd (1), I realize that my nighttime communion with this adult voice was shared by thousands of other kids. He fused the nonconformist sensibility of the Beats and the Hips with a Midwestern distaste for airs and pomposity. He called his fans the Night People. The enemies were the Meatballs, the Slobs, or, in a reference to a Pepsi tagline, the Sociables. He spurred his listeners to send Cassavetes money to fund Shadows; a credit to the Night People appears on the movie. Shep’s motto was “Excelsior” (sometimes, “Excelsior, you fathead”), which encapsulated both his optimism (onward and upward, keep striving) and his fatalism (remember the boy with the banner lying frozen in the snow).

Urged on by Bergmann’s book, I recently discovered a wonderful Shepherd website and a vast podcast vault of his shows, which are also available free on iTunes. (2) Broadcast a little before I started listening, the 1960 “Molded Food” episode was a great iPod companion as I wandered around the UT—Austin campus.

Put not aside childish things

I could mention more items seen through my window, such as the Village Voice, Esquire, and, inevitably, Mad magazine. But the moral should be clear. Whatever called out to you when your window opened—Grease, Patti Smith, Buckaroo Banzai, Sassy, David Bowie, Columbo, Godspell, Lord of the Rings (the book), Penn and Teller, National Lampoon, Pavement, John Hughes movies, Kurt Vonnegut, the B-52s, Earth Girls Are Easy, Beat Street, Master of Puppets, Boondock Saints, Sam Kinison, They Might Be Giants, you name it—is likely to retain its bright purity throughout your days. What’s kitsch or cheesy or retro to others is precious to you.

Make no apologies. It’s not mere nostalgia or guilty pleasure to revisit these creations. You can return to them as to old friends. Encountering them again, you remember when you took it for granted that anything was possible in your life. Their sharp, shining lines fitted your range of vision, and mostly they still do.

Your taste was unerring. These teenage passions represent a big chunk of the finest part of you. In some secret place you are still as uncomplicated as you were then.

(1) Eugene B. Bergmann, Excelsior, You Fathead! The Art and Enigma of Jean Shepherd (New York: Applause, 2005).

(2) In the iTunes store, go to “The Brass Figlagee” under Podcasts.

Thanks to Jeff Smith, Jonah Horwitz, and Dan Morgan for suggesting some things they saw through their adolescent window.

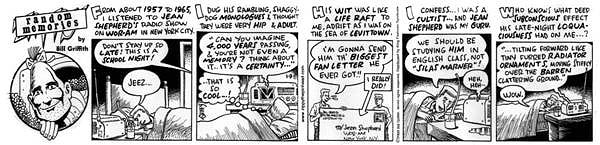

Zippy the Pinhead, by Bill Griffith.

You may own the night, but I’ve got a lien on midday

DB here:

Since I retired, I usually go to matinee shows. It’s cheaper, and the auditorium is depopulated. Sometimes I’m the only person there. I know, movies are supposed to be seen with a big audience; but I’ve seldom liked the experience of a packed house. Does the humble worshipper in the temple need a congregation to confirm his faith? Isn’t it best to commune with the deity alone? More to the point: Even before the advent of cellphones, somebody always coughs or talks at the wrong time.

If there are any other people around during my matinees, they are likely to be elderly folks, misfits, losers, idlers, and troublemakers. This makes me feel superior. But then I realize that to an objective observer, I could fit into any of those categories. Last time I went to my local, the cashier at the ticket stand gave me the Senior Citizens discount automatically. The pleasure of saving a dollar was small compensation for the blow to baby-boomer pride—sort of the reverse of being carded at a bar when you’re 30.

Curiously, as film attendance is dropping, multiplexes are offering more screenings. I enjoyed the idea of starting the screening cycle at noon or so, but now some ‘plexes start running as early as 10:30. At my neighborhood ‘plex, you can attend the Baby Box Office (“The lights are a little brighter, the sound a little softer”) on Tuesdays at 10:00 AM. It’s currently featuring the ideal picture for babes in arms, American Gangster.

Here are some jotted opinions on movies seen at midday over the last couple of weeks.

We Own the Night: I admired James Gray’s The Yards, but this seemed to me quite standard. One brother’s a cop, the other’s on the shady side: back to Warner Bros. of the 1930s. (Where’s the tough priest, though?) Although set in the 1980s, it looks a bit like a 1970s movie, with all those long-lens shots and flattened color values. The plot was by-the-numbers, and lines like “You’re a dead man” and “I love you very much” don’t help. I guess it’s a “personal” project for Phoenix and Wahlberg, both brave performers in other vehicles but mostly going through the motions here. Further evidence that today’s cinema is classic studio cinema, with more sex, violence, drugs, and rock-and-roll.

We Own the Night: I admired James Gray’s The Yards, but this seemed to me quite standard. One brother’s a cop, the other’s on the shady side: back to Warner Bros. of the 1930s. (Where’s the tough priest, though?) Although set in the 1980s, it looks a bit like a 1970s movie, with all those long-lens shots and flattened color values. The plot was by-the-numbers, and lines like “You’re a dead man” and “I love you very much” don’t help. I guess it’s a “personal” project for Phoenix and Wahlberg, both brave performers in other vehicles but mostly going through the motions here. Further evidence that today’s cinema is classic studio cinema, with more sex, violence, drugs, and rock-and-roll.

Gone Baby Gone: At least We Own the Night doesn’t promise to be more than a typical genre piece. For several years now, many ambitious or “prestige” pictures have given genres the uplift treatment, making them—well, serious. So a crime thriller that might have been trim at 90 minutes gets padded out to portentous dimensions, chiefly through scenery-gobbling performances and tricky narration. A recent model is The Departed, but Mystic River also worked this ground.

Such is Gone Baby Gone, another Lehane exercise in male pain in a gritty ethnic enclave. Director Ben Affleck shoots it in a standard way, with long-lens glimpses of homely people sitting on stoops (don’t get too close), and he resorts to the now-common device of flashbacks that fill us in on what really happened in a crucial scene. As usual in such fare, the plot is a pretext for Oscar-bait performances, and I confess that to my surprise I found Casey Affleck pretty riveting.

Michael Clayton: Another tricked-out genre effort, with echoes of Three Days of the Condor. Again a mystery plot is overlaid with a guy’s personal problems: divorce, druggy brother, loyalty to his mentor. (By the way, when is someone going to do a study of the hero’s weak friend in Hollywood cinema?) We get the fancy flashbacks as well, starting at a high point—an exploding car bomb, which ought to grab you—before a title pops up: “Four days earlier.” Eventually, as per usual nowadays, the opening scene is replayed, from a more omniscient point of vantage. And just as I have problems with any movie that resolves its plot with somebody writing a check, I don’t find it terribly original to settle things by secretly taping the bad guys admitting their chicanery. Yet I appreciated Paul Gilroy’s calm direction. I especially liked his crosscut sequences, in which the sound of one line of action plays out over images from the other line. This technique isn’t brand-new, but Gilroy handles these passages well, building story momentum while creating compact characterizing bits (e.g., the insecurity of lawyer Tilda Swinton faced with critical meetings).

Michael Clayton: Another tricked-out genre effort, with echoes of Three Days of the Condor. Again a mystery plot is overlaid with a guy’s personal problems: divorce, druggy brother, loyalty to his mentor. (By the way, when is someone going to do a study of the hero’s weak friend in Hollywood cinema?) We get the fancy flashbacks as well, starting at a high point—an exploding car bomb, which ought to grab you—before a title pops up: “Four days earlier.” Eventually, as per usual nowadays, the opening scene is replayed, from a more omniscient point of vantage. And just as I have problems with any movie that resolves its plot with somebody writing a check, I don’t find it terribly original to settle things by secretly taping the bad guys admitting their chicanery. Yet I appreciated Paul Gilroy’s calm direction. I especially liked his crosscut sequences, in which the sound of one line of action plays out over images from the other line. This technique isn’t brand-new, but Gilroy handles these passages well, building story momentum while creating compact characterizing bits (e.g., the insecurity of lawyer Tilda Swinton faced with critical meetings).

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford: The really successful fancy-pants genre film in my latest round of viewings. Andrew Dominik has made a grave, spare movie about the myth of Jesse and his murderer that doesn’t splash on period details and swamp the action in overproduced sets. The film could have been another funny-hats Western, but it turns out to be as austere as a sharecropper’s porch in a Walker Evans photograph. With an average shot length close to seven seconds, the film lets actors use their bodies a bit and interact within a fixed frame. In this context, the vignetted shots stand out, but not as mere flourishes; their wavery softness is picked up in the distorting windowpanes of the farmhouses and eventually in the fatal reflection in the picture Jesse is adjusting.

For once a post-Unforgiven western earns its meta-commentary on the Legends of the West. Jesse is the quietly charismatic star, while Ford is the overeager admirer, the outlaw as groupie. Daringly, the plot wanders away from its main characters for considerable stretches, and the protracted dialogues feature archaic turns of speech that can become ominous. Jesse is a raconteur whose paranoia can unnerve anybody: “You got a tale to swap with me now?” Assassination also reminded me of Magnolia in the dry authority of its voice-over narration and in its epilogue, which follows Ford to the end of his enigmatic life.

But where am I at the peak hours on Friday and Saturday, when throngs at the multiplex line up for popcorn, nachos and Dots? At our cozy Cinematheque, where we screen dazzling items like Nouvelle Vague and Utamaro and His Five Women. Right now, Godard and Mizoguchi own my nights.