Archive for May 2008

Some cuts I have known and loved

DB here, belatedly:

We’ve been so busy revising our textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for its third edition that we’ve had no time to see new movies, let alone blog on our regular schedule. To those loyal readers who have been checking back occasionally, we say: Thanks for your patience. An entry that should intrigue you is in the works, possibly to be posted very soon.

In the meantime, here’s an item on a subject I’ve been meaning to slip in at some point. It’s a tribute to cuts I admire.

Warning: Superb as Eisenstein’s, Ozu’s, and Hitchcock’s cuts are, I’m deliberately leaving them out. Too obvious!

Kata and cutting

Okay, Kurosawa is an obvious choice too, but I can’t pass up some of the first outstanding cuts I noticed in his work, back when I was projecting movies for my college film society. The cuts occur during the climactic battle of Seven Samurai (1954).

As is well-known, Kurosawa shot the sequence with several cameras using different focal-length lenses. What is less often acknowledged, I think, is the power of certain cuts as they combine with fixed camera positions. In his last films, Kurosawa would rely strongly on long-lens shots that pan over the pageantry of his crowd scenes, but here he exploits static frames.

In the eye of the battle, Kambei fires his arrow in one shot, and a horseman falls victim to his marksmanship in the next. So far, so conventional. But what’s unusual is that we don’t actually see the arrow hit its target. Kambei fires, and Kurosawa cuts to an empty bit of the town square, churned with mud and dimly visible through horses’ legs. Only after an instant does a fallen bandit skid into the telephoto frame.

The same thing happens when Kambei shoots his second arrow: we must wait for the victim to plunge into the frame.

The result, I think, is a sense of exhilarating inevitability. The camera knows that the horseman will fall, and it knows exactly where. That’s a way of saying that Kurosawa’s visual narration fulfills our expectation, but with a slight delay. The empty frame prompts us to anticipate that the man will be hit—why else show it?—and we have a moment of suspense in waiting to confirm what we expect. Moreover, the force of Kambei’s arm is given us through a principle of Movie Physics: motion communicated to another body is magnified, not diminished, and the fixed frame allows us to see just how far the bodies are propelled. The arrow must have been Homerically powerful if it sends these men to earth with such impact.

Most directors would have panned to follow the victim as, wearing the arrow, he tumbled off his horse and hit the ground. This choice would have been natural given the multiple-camera situation. Instead Kurosawa had his camera operators frame the exact spot the stuntman would hit and wait for the action to hurtle into the shot. The patient expertise of Kambei’s marksmanship has its counterpart in the confidence of Kurosawa’s style. (1)

The moving image, Mr. Griffith, and us

Then there’s Intolerance (1916).

The Musketeer of the Slums is trying to seduce the young man’s wife, the Dear One. He pretends he can retrieve her baby. But his earlier conquest, the Friendless One, has followed him to the tenement, and at the same time the Boy has learned about the Musketeer’s visit. As the Musketeer attacks the Dear One, the Boy bursts in. The two men struggle and the Boy is momentarily knocked out; the Dear One has swooned. So no one sees what really happens next: From the window ledge the Friendless One fires her pistol and downs the gangster. She flees, and the boy believes that he is the killer. He will be charged with the murder.

Here’s what I admire. Griffith sets the situation up with his usual rapid crosscutting—the Musketeer and the Dear One struggling, the Boy returning, and the Friendless One crawling out on the ledge. When the fight starts, Griffith shows the Friendless One growing wild-eyed at the window. She fires once, and Griffith gives the action to us in three shots: a medium shot of her in profile, a medium-long shot of the pistol at the window (irised so we notice it), and a long-shot of the room, as the Musketeer is hit.

Griffith repeats the series of shots when the Friendless One fires again.

This time the Musketeer staggers out to the hall and dies. Neatly, Griffith gives us three more shots, but omits the setup showing the Friendless One. Cut to the curtains again, with her hand waving the pistol, then to another long shot of the room as the gun is tossed in, and finally to a close-up of the pistol landing on the floor.

If you’re looking for a pattern, the pistol in close-up is in effect substituted for the shot of the Friendless One at the start of each cycle. But I’m most interested in the shots of the pistol. The first one at the window goes by at blinding speed—ten frames in the two prints Kristin and I have examined. (2) That works out to a bit more than half a second, if you assume 16 frame per seconds as the projection rate, which was common at the time.

Okay, fussy, but I’ve already confessed that I turn into a frame-counter, when I get the chance. The second shot of the pistol poking out of the curtains, parallel to the first, is also ten frames long. Griffith seems to have been a frame-counter too.

What’s most remarkable is that the long-shot of the pistol being flung into the room is even briefer than these closer views—only seven frames long, or less than half a second at 16fps. As a nice touch, the close-up of the pistol landing in the corner is twice that (15 frames).

In the decades that followed, directors would believe that long shots shouldn’t be cut as fast as close-ups, so the Intolerance passage can strike us as a typical Griffith misjudgment. But I admire his willingness to cut long shots so fast. It certainly creates a percussive accent. In case we didn’t catch the story point, the close-up of the pistol hitting the floor clinches it.

This is the sort of sequence that the Soviet filmmakers probably learned from. They may even have gotten ideas from Griffith’s interspersed black frames (two by my count) before each of the shots of the pistol thrusting out of the curtain. (3)

Behind the desk

Speaking of the Russians, one of my favorite cuts in Pudovkin’s movies comes during a confrontation in The End of St. Petersburg (1927). The somewhat oafish young worker known only as the Lad, who has sold out his comrades, attacks the boss Lebedev in his office. He seizes the boss and shoves him down, jamming him between his desk and the window. We see the action from one angle and then what seems to be an opposing angle.

Actually, this is a big discontinuity. Using the desk, the telephone, and the window as reference points, we can see that in the first shot, the Lad moves in from the left side of the desk to push the boss down. In the second, he has come in from the right side and Lebedev’s head is pointing in the opposite direction. We can see the weirdness of this more clearly if we simply flip one of the frames: now it looks like a consistent change of angle.

Pudovkin has created an impossible event. But the cut gives the strong sense of graphic conflict that the Soviets (not just Eisenstein) sought, creating a kind of visual clatter to underscore the violence of the action. It’s possible that Pudovkin actually flipped a “correct” framing to create the disjunction, as some of his contemporaries did. (4)

Meg, all aflutter

Pudovkin’s cut reminds us that filmmakers can get away with a lot if they change the angle drastically. It’s harder to spot a cheated element or a mismatch if the new shot makes us reorient ourselves. Why does this happen? That’s a subject for research, as I’ll suggest at the end.

Here’s another tricky item. In Kate & Leopold (2001), Kate has brought her time-traveling guest to an audition for a butter commercial. In the studio, he’s behind her as she tries to convince her colleagues to watch him. As she talks, she first watches Leopold in the monitor above them, then swivels to talk to her boyfriend and other suits. The camera positions change 180 degrees.

This drastic shift works to prepare us for a remarkable cut a little later. Kate waves her hand, saying she only needs two minutes. She pivots her body, moving her hand downward.

Cut 180 degrees to a setup similar to the one we’ve seen earlier: She drops her hand to her side as she swings to us.

The gesture is smoothly matched. The only trouble is that it’s executed by the wrong hand. In the first shot Kate is wiggling her left hand, but in the second, it’s her right hand that continues the movement and drops to her hip.

I don’t think that many people would notice this. Indeed, when I first saw the film, I felt a bump hereabouts, but when I watched it over again on DVD, it looked fine to me. Then I watched it again and saw what was wrong. Even then, I thought I might be hallucinating. It’s one of the trickiest cheats I know of, and it’s beautifully done.

The real question is: Why don’t we notice it? We usually say, “Because we’re watching the story and ignore little irregularities.” But that’s not very satisfactory. Why isn’t the wave of Kate’s hand part of the story? We certainly notice it as expressing her attitude—hence as part of the story. And if you didn’t notice the disjunction in my End of St. Petersburg example, the same question arises: Isn’t the Lad’s attack on the boss the very story action we’re watching?

Consider the alternative. If director James Mangold had matched the left hand, it would have to cross the center of the frame as Kate pivots, shifting from screen left to screen right before landing at her hip. It would have been ostentatious and somewhat graceless, and perhaps that would have been distracting. So the mismatch is perhaps a line of least resistance, a compromise–as so many stylistic choices are.

In addition, Kristin suggests that our pickup is made easier by the placement and action of the hand. In both shots it’s quite central and moving in the same direction at the same rate, so that it’s easy to read as a graphically continuous element across the cut.

Perhaps too the fact that we’re switching our position 180 degrees leads us to expect, wrongly, the sort of reversal we get here—the way that we think our reflection in a mirror is the way we really look. And of course the earlier 180-degree switch, in which no mismatch occurs, probably serves to prime us for the shift in orientation this provides.

Mangold doesn’t mention the cut in his director’s commentary on the Kate & Leopold DVD, but when I asked him he said: “I think of shots as blocks, like legos or words. I don’t want them to resolve–come to an end. . . . Movement cuts work as long as the action is somewhat similar. The tough continuity cuts when you have a mismatch are the still ones.” Even if the mismatch here was accidental, it works very well. More generally, like other mismatches this one obliges us to think about what we see and what we don’t see when we watch a movie.

Hawks’ eyes

Among the many pleasures of Howard Hawks’ movies are their lovely matches on action. Of course his editors had a lot to do with this, but Hawks clearly had to provide the right footage so that it could be precisely matched. Bringing Up Baby (1938) yields a crisp cut as Susan, perched on the constable’s desk, strikes a match. (I show the cuts from a 16mm print; enough of this video stuff.)

Here Hawks seems to rely on what’s been called the two-frame rule: If you’re going to match on action, overlap the action by two frames to show a bit of the action again. This allows the audience time to absorb the fact of the cut and then to see the action as continuous. But Hawks could be quite cavalier about his matches as well. The golfing scene from Bringing Up Baby is full of wild cuts.

The caddies advance and recede, Susan and David are caught in different postures, and at some cuts they’re striding across different parts of the course. These cuts have a swagger about them, as if Hawks is daring us to spot his outrageous cheats. How many of us do?

All these trompe l’oeil effects can be studied psychologically, and prominent researchers who have tested such effects in the laboratory are attending our 11-14 June meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. Dan Levin studies discontinuities in film from the standpoint of “inattentional blindness”; here he’s interviewed by Errol Morris. Barry Hughes of Arizona State University at Tempe has probed the two-frame rule, and he’s talking in Madison as well. Go here for more information; I’ve plugged the event previously here.

Next time, we expect: Secrets of film restoration.

(1) Kurosawa has prepared us for this passage when Kikuchiyo’s sword attacks the bandits earlier in the sequence. There too a shot of his flailing stroke is followed, after a pause on a patch of mud, by a falling horseman. But the calm deliberateness of Kambei’s drawing of his bow enhances the sense of inevitability, I think. Kiku does his damage through furious energy, but Kambei hits his mark thanks to a mature warrior’s almost contemplative precision.

(2) Forget checking these frame counts on DVD. I get several different counts, depending on the player I use. For reasons discussed here, DVDs don’t preserve the original film frames, and in a fast-cut passage you can lose any sense of how many frames the shot lasted.

(3) By the way, Griffith died on 23 July 1948, my first birthday.

(4) For more on this extraordinary movie’s use of discontinuity editing, see Vance Kepley, Jr., The End of St. Petersburg (London: Tauris, 2003).

In critical condition

DB here:

A Web-prowling cinephile couldn’t escape all the talk about the decline of film criticism. First, several daily and weekly reviewers left their print publications, as Anne Thompson points out. Then one of our brightest critics, Matt Zoller Seitz, suspended writing in order to return to film production. This and the departure of another web critic, Raymond Young of Flickhead, has prompted Tim Lucas to ponder, at length and in depth, why one would maintain a film blog. Go to Moviezzz for a summing up.

I’ve been teaching film history and aesthetics since the early 1970s, but before that I wrote criticism for my college newspaper, the Albany Student Press, and then for Film Comment. When I set out for graduate school, film criticism was virtually the only sort of film writing I thought existed. Auteurism was my faith, and Andrew Sarris its true apostle (for reasons explained in an essay in Poetics of Cinema). In grad school, I learned that there were other ways of thinking about cinema. Since then, I’ve tried to steer a course among film criticism, film history, and film theory—sometimes doing one, sometimes mixing them. But criticism has remained central to my interest in cinema.

What, though, does the concept mean? I think that some of the current discussions about the souring state of movie criticism would benefit from some thoughts about what criticism is and does.

Watch your language

Consider criticism as a language-based activity. What do critics do with their words and sentences? Long ago, the philosopher Monroe Beardsley laid out four activities that constitute criticism in any art form, and his distinctions still seem accurate to me. (1) We use them in Chapter 2 of Film Art.

*Critics describe artworks. Film critics summarize plots, describe scenes, characterize performances or music or visual style. These descriptions are seldom simply neutral summaries. They’re usually perspective-driven, aiding a larger point that the critic wants to make. A description can be coldly objective or warmly partisan.

*Critics analyze artworks. For Beardsley, this means showing how parts go together to make up wholes. If you simply listed all the shots of a scene in order, that would be a description. But if you go on to show the functions that each shot performs, in relation to the others or some broader effect, you’re doing analysis. Analysis need not concentrate only on visual style. You can analyze plot construction. You can analyze an actor’s performance; how does she express an arc of emotion across a scene? You can analyze the film’s score; how do motifs recur when certain characters appear? Because films have so many different kinds of “parts,” you can analyze patterns at many levels.

*Critics interpret artworks. This activity involves making claims about the abstract or general meanings of a film. The word “interpret” is used in lots of ways, but in the sense meant here, figuring out the chronological order of scenes in Pulp Fiction wouldn’t count. If, though, you claim that Pulp Fiction is about redemption, both failed (Vincent) and successful (Jules’ decision to quit the hitman trade), you’re launching an interpretation. If I say that Cloverfield is a symbolic replay of 9/11, that counts as an interpretation too.

*Critics evaluate artworks. This seems pretty straightforward. If you declare that There Will Be Blood is a good film, you’re evaluating it. For many critics, evaluation is the core critical activity; after all, the word critic in its Greek origins means judge. Like all the other activities, however, evaluation turns out to be more complicated than it looks.

Why break the process of criticism into these activities? I think they help us clarify what we’re doing at any moment. They also offer a rough way to understand the critical formats that we usually encounter.

In paper media, on TV, or on the internet, we can distinguish three main platforms for critical discussion. A review is a brief characterization of the film, aimed at a broad audience who hasn’t seen the film. Reviews come out at fixed intervals—daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly. They track current releases, and so have a sort of news value. For this reason, they’re a type of journalism.

An academic article or book of criticism offers in-depth research into one or more films, and it presupposes that the reader has seen the film (or doesn’t mind spoilers). It isn’t tied to any fixed rhythm of publication.

A critical essay falls in between these types. It’s longer than a review, but it’s usually more opinionated and personal than an academic article. It’s often a “think piece,” drawing back from the daily rhythm of reviewing to suggest more general conclusions about a career or trend. Some examples are Pauline Kael’s “On the Future of Movies” and Philip Lopate’s “The Last Taboo: The Dumbing Down of American Movies.” (2) Critical essays can be found in highbrow magazines like The New Yorker and Artforum, in literary quarterlies, and in film journals like Film Comment, CinemaScope, and Cahiers du Cinéma.

Any critic can write on all three platforms. Roger Ebert is known chiefly for his reviews, but his Great Movies books consist of essays. (3) J. Hoberman usually writes reviews, but he has also published essays and academic books. And the lines between these formats aren’t absolutely rigid, as I’ll try to show later.

Reviewing reviewers

How do these forums relate to the different critical activities? It seems clear that academic criticism, the sort published in research articles or books, emphasizes description, analysis, and interpretation. Evaluation isn’t absent, but it takes a back seat. Usually the academic critic is concerned to answer a question about the films. How, for instance, is the theme of gender identity represented in Rebecca, and what ambiguities and contradictions arise from that process? In order to pursue this question, the critic needn’t declare Rebecca a great film or a failure.

Of course, the academic piece could also make a value judgment, either at the outset (I think Rebecca is excellent and want to scrutinize it) or at the end (I’m forced to conclude that Rebecca is a narrow, oppressive film). But I don’t have to pass judgment. I have written about a lot of ordinary films in my life. They became interesting because of the questions I brought to them, not because they had a lot going for them intrinsically.

The academic article has a lot of space to examine its question—several thousand words, usually—and of course a book offers still more real estate. By contrast, a review is pinched by its format. It must be brief, often a couple of hundred words. Unlike the academic critique, the review’s purpose is usually to act as a recommendation or warning. Most readers seek out reviews to get a sense of whether a movie is worth seeing or even whether they would like it.

Because evaluation is central to their task, reviewers tend to focus their descriptions on certain aspects of the film. A reviewer is expected to describe the plot situation, but without giving away too much—major twists in the action, and of course the ending. The writer also typically describes the performances, perhaps also the look and feel of the film, and chiefly its tone or tenor. Descriptions of shots, cutting patterns, music, and the like are usually neglected. And what is described will often be colored by the critic’s evaluation. You can, for instance, retell the plot in a way that makes your opinion of the film’s value pretty clear.

Reviews seldom indulge in analysis, which typically consumes a lot of space and might give away too much. Nor do reviewers usually float interpretations, but when they do, the most common tactic is reflectionism. A current film is read in relation to the mood of the moment, a current political controversy, or a broader Zeitgeist. A cynic might say that this is a handy way to make a film seem important and relevant, while offering a ready-made way to fill a column. Reviewers don’t have a monopoly on reflectionism, though. It’s present in the essayistic think-piece and in academic criticism too. (4)

The centrality of evaluation, then, dictates certain conventions of film reviewing. Those conventions obviously work well enough. But we can learn things about cinema through wide-ranging descriptions and detailed analyses and interpretations, as well. We just ought to recognize that we’re unlikely to get them in the review format.

The good, the bad, and the tasty

Let’s look at evaluation a little more closely. If I say that I think that Les Demoiselles de Rochefort is a good film, I might just be saying that I like it. But not necessarily. I can like films I don’t think are particularly good. I enjoy mid-level Hong Kong movies because I can see their ties to local history and film history, because I take delight in certain actors, because I try to spot familiar locations. But I wouldn’t argue that because I like them, they’re good. We all have guilty pleasures—a label that was coined exactly to designate films which give us enjoyment, even if by any wide criteria they aren’t especially good.

They needn’t be disastrously bad, of course. I do like Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, inordinately. It’s my favorite Demy film and a film I will watch any time, anywhere. It always lifts my spirits. I would take it to a desert island. But I’m also aware that it has its problems. It is very simple and schematic and predictable, and it probably tries too hard to be both naive and knowing. Artistically, it’s not as perfect as Play Time or as daring as Citizen Kane or as….well, you go on. It’s just that somehow, this movie speaks to me.

The point is that evaluation encompasses both judgment and taste. Taste is what gives you a buzz. There’s no accounting for it, we’re told, and a person’s tastes can be wholly unsystematic and logically inconsistent. Among my favorite movies are The Hunt for Red October, How Green Was My Valley, Choose Me, Back to the Future, Song of the South, Passing Fancy, Advise and Consent, Zorns Lemma, and Sanshiro Sugata. I’ll also watch June Allyson, Sandra Bullock, Henry Fonda, and Chishu Ryu in almost anything. I’m hard-pressed to find a logical principle here.

Taste is distinctive, part of what makes you you, but you also share some tastes with others. We teachers often say we’re trying to educate students’ tastes. True, but we should admit that we’re trying to broaden their tastes, not necessarily replace them with better ones. Elsewhere on this site I argue that tastes formed in adolescence are, fortunately, almost impossible to erase. But we shouldn’t keep our tastes locked down. The more different kinds of things we can like, the better life becomes.

The difference between taste and judgment emerges in this way: You can recognize that some films are good even if you don’t like them. You can declare Birth of a Nation or Citizen Kane or Persona an excellent film without finding it to your liking.

Why? Most people recognize some general criteria of excellence, such as originality, or thematic significance, or subtlety, or technical skill, or formal complexity, or intensity of emotional effect. There are also moral and social criteria, as when we find films full of stereotypes objectionable. All of these criteria and others can help us pick out films worthy of admiration. These aren’t fully “objective” standards, but they are intersubjective—lots of people with widely varying tastes accept them.

So critics not only have tastes; they judge. The term judgment aims to capture the comparatively impersonal quality of this sort of evaluation. A judge’s verdict is supposed to answer to principles going beyond his or her own preferences. Judges at a gymnastic contest provide scores on the basis of their expertise and in recognition of technical criteria, and we expect them to back their judgment with detailed reasons.

One more twist and I’m done with distinctions. At a higher level, your tastes may make you weigh certain criteria more heavily than others. If you most enjoy movies that wrestle with philosophical problems, you may favor the thematic-significance criterion. So you’ll love Bergman and think he’s a great director. In other words, you can have tastes in films that you also consider excellent. Presumably this is what we teachers are trying to cultivate as well: to teach people, as Plato urged, to love the good.

Of course we can disagree about relevant criteria, particularly about what criteria to apply to a particular movie. I’d argue that profundity of theme isn’t a very plausible criterion for judging Cloverfield; but formal originality, technical skill, and intensity of emotional appeal are plausible criteria to apply. Many of the best Hong Kong films don’t apply rank high on subtlety of theme or character psychology, but they do well on technical originality and intensity of visceral and emotional response. You may disagree, but now we’re arguing not about tastes but about what criteria are appropriate to a given film. To get anywhere, our conversation will appeal to both intersubjective standards and discernible things going on in the movie–not to whether you got a buzz from it and I didn’t.

There’s a reason they call that DVD series Criterion

Now back to film reviewing. Judgment certainly comes into play in a film review, because the critic may invoke criteria in evaluating a movie. Such criteria are widely accepted as picking out “good-making” features. For instance:

The plot makes no sense. Criterion: Narrative coherence helps make a film, or at least a film of this sort, good.

The acting is over the top. Criterion: Moderate performance helps make a film, or at least a film of this sort, good.

The action scenes are cut so fast that you can’t tell what’s going on. Criterion: Intelligibility of presentation helps make a film, or at least a film of this sort, good.

Most reviewers, though, can’t resist exposing their tastes as well as their judgments. This is a convention of reviewing, at least in the most high-profile venues. Readers return to reviewers with strongly expressed tastes. Some readers want to have their own tastes reinforced. If you think Hollywood pumps out shoddy product, Joe Queenan will articulate that view with a gonzo relish that gives you pleasure. Other readers want to have their tastes educated, so they seek out a strong personality with clear-cut tastes to guide them. Still other readers want to have their tastes tested, so they read critics whose tastes vary widely from theirs. I’m told that many people read Armond White for this reason. Tastes come in all flavors.

Celebrity critics—the reviewers who attract attention and controversy—are usually vigorous writers who have pushed their tastes to the forefront. Top critics like Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael are famous partly because they flaunted their tastes and championed films that they liked. (Of course they also thought that the films were good, according to widely held criteria.) It isn’t only a matter of praise, either. Every so often critics launch all-out attacks on films, directors, or other critics, and some are permanently cranky. Movie reviewer Jay Sherman (above) ranks films by analogy to diseases. Hatchet jobs assure a critic notoriety, but they also prove Valéry’s maxim that “Taste is made of a thousand distastes.”

At a certain point, celebrity critics may even give up justifying their evaluations altogether, simply asserting their preferences. They trust that their track record, their brand name, and their forceful rhetoric will continue to engage their readers. It seems to me that after decades of stressing the individuality of their tastes, many of the most influential reviewers are emitting two main messages: You see it or you don’t and Differ if you dare. I’d like to see more argument and less strutting. But then, that’s my taste.

Stuck in the middle, with us

There’s much more to say about the distinctions I’ve floated. They are rough and need refining. But they’ll do for my purpose today, which is to indicate that everything I’ve said can apply to Web writing.

For instance, it seems likely that one cause of critical burnout is that reviews dominate the Net. They’re typically highly evaluative, mixing taste and judgment. Many people will find a bombardment of such items eventually too much to take. I could imagine somebody abandoning Net criticism simply because of the cacophony of shrieking one-liners. We’re all interested in somebody else’s opinions, but we can’t be interested in everybody else’s opinions.

In addition, the distinguishing feature among these thousands of reviews won’t necessarily be wit or profundity or expertise, but style. I think that, years ago, the urge toward self-conscious critical style arose from the drudgery of daily reviewing. Faced with a dreadful new movie, you could make your task interesting only by finding a fresh way to slam it. In addition, magazines that wanted to appear smart encouraged writers to elevate attitude above ideas. In the overabundance of critical talk on the Net, saying “It’s great” or “It stinks” in a clever way will draw more attention than plainer speaking, but even that novelty will wear off eventually.

Fortunately, there are other formats available to cybercriticism. At first glance, the Web seems to favor the snack size, the 150-word sally that’s all about taste and attitude. In fact, the Net is just as hospitable to the long piece. There are in principle no space limitations, so one can launch arguments at length. (It’s too long to read scrolling down? Print it out. Maybe you have to do that with this essay.) Thanks to the indefinitely large acreage available, one of the heartening developments of Web criticism is the growth of the mid-range format I’ve mentioned: the critical essay.

Historically, that form has always been closer to the review than to the academic piece. It relies more on evaluation. That’s centrally true of the Kael and Lopate essays I mentioned above, both of which warn about disastrous changes in Hollywood moviemaking. But the tone can be positive too, most often seen in the appreciative essay, which celebrates the accomplishment of a film or filmmaker. Dwight Macdonald’s admiring piece on 8 ½ and Susan Sontag’s 1968 essay on Godard, despite their differences, seem to me milestones in this genre. (5)

The critical essay is, I think, the real showcase for a critic’s abilities. We say that good critics have to be good writers, usually meaning that their style must be engaging, but it doesn’t have to explode at the end of every paragraph. More generally, in a long essay, you are forced to use language differently than in a snippet. You need to build and delay expectations, find new ways to repeat and modify your case, and seek out synonyms.

Just as important, the long piece separates the sheep from the goats because it shows a critic’s ability to sustain a case. The short form lets you pirouette, but the extended essay—unless it’s simply a rant—obliges you to show all your stuff. In the long form, your ideas need to have heft. Stepping outside film for a moment, consider Gary Giddins on Jack Benny, or Geoffrey O’Brien on Burt Bacharach, or Robert Hughes on Goya, and in each you will see a sprightly, probing, deeply informed mind develop an argument in surprising ways. (6) Strikingly, all these writers venture into subtleties of analysis and interpretation, putting them close to the academic model. So who needs footnotes?

Above all, the critical essay can develop new depth on the Web. Given more space, the Web can ask critics to lay out their assumptions and evidence more fully. After years of “writing short,” of firing off invectives, put-downs, and passing paeans to great filmmakers unknown to most readers, critics now have an opportunity—not to rant at greater length but to go deeper. If you think a movie is interesting or important, please show us. Don’t simply assert your opinion with lots of hand-waving, but back it up with some analysis or interpretation. The Web allows analysis and interpretation, which take a lot of effort, to come into their own.

Need an example? Jim Emerson, time and again. There are plenty of other instances hosted by journals like Rouge and the extraordinary Senses of Cinema, and many solo efforts, such as a recent one from Benjamin Wright.

Some will object that this is a pretty unprofitable undertaking. Who’ll pay people to write in-depth critical studies on the movies they find compelling? Well, who’s paying for all those 100-word zingers? And who has paid those programmers who continue to help Linus Torvalds develop Linux? People do all kinds of things for love of the doing and for the benefit of strangers. Besides, no one should expect that writing Web criticism will pay the bills. If Disney can’t collect from people who have downloaded Pirates of the Caribbean 3 for free, why should you or I expect to be paid for talking about it? Maybe only idlers, hobbyists, obsessives, and retirees (count me among all four) have the leisure to write long for the Web.

I envision another way to be in the middle. If most critical essays have been akin to reviews, what about essays that lie closer to the other extreme, the academic one? I’d like to see more of what might be called “research essays.” If the critical essay of haut journalism tips toward reviewing while being more argument-driven, the research essay leans toward academic writing, while not shrinking from judgment, and even parading tastes. I’ve tried my hand at several research essays, in books as well as in pieces you’ll find on the left side of this page; and occasionally one of our blog entries moves in this direction.

This isn’t to discourage people from jotting down ideas about movies and triggering a conversation with readers. The review, professional or amateur, shouldn’t go extinct. But we also benefit from ambitious critical essays, pieces that illuminate movies through analysis and interpretation. Web critics could write less often, but longer. In an era of slow food, let’s try slow film blogging. It might encourage slow reading.

(1) Monroe K. Beardsley, Aesthetics: Problem in the Philosophy of Art Criticism (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1958), 75-78.

(2) Pauline Kael, “On the Future of Movies,” in Reeling (New York: Warner Books, 1977), 415-444; Philip Lopate, “The Last Taboo: The Dumbing Down of American Movies,” in Totally Tenderly Tragically: Essays and Criticism from a Lifelong Love Affair with the Movies (New York: Anchor, 1998), 259-279.

(3) In addition, Ebert often manages to build his daily pieces around a general idea, not necessarily involving cinema, so he can be read with enjoyment by people not particularly interested in film. I talk about this a little in my introduction to his collection Awake in the Dark.

(4) Reflectionist interpretation usually seems to me unpersuasive, for reasons I’ve discussed in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 30-32. I realize that I’m tilting at windmills. Reflectionism will be with us forever.

(5) Dwight Macdonald, “8 ½: Fellini’s Obvious Masterpiece,” in On Movies (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969), 15-31; Susan Sontag, “Godard,” in Styles of Radical Will (New York: Delta, 1969), 147-189.

(6) Gary Giddins, “’This Guy Wouldn’t Give You the Parsley off His Fish,’” in Faces in the Crowd: Musicians, Writers, Actors, and Filmmakers (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), 3-13; Geoffrey O’Brien, “The Return of Burt Bacharach,” in Sonata for Jukebox: Pop Music, Memory, and the Imagined Life (New York: Counterpoint, 2004), 5-28; and Robert Hughes, “Goya,” in Nothing If Not Critical: Selected Essays on Art and Artists (New York: Penguin, 1992), 50-64. I pay tribute to Giddins as a critic elsewhere on this site. Hughes later wrote a fine monograph on Goya.

Cavalcanti + Ealing = a little-known gem

Went the Day Well? A traitor gives information to a German infiltrator, who takes notes against a memorial to World War I dead

Kristin here—

As David and I sit here revising our Film History textbook for its third edition, we’re looking forward to the annual Il Cinema Ritrovato film festival in Bologna (June 28-July 5). We blogged from there last year and plan to do so again this year.

One of the festival’s themes in recent years has been World War II. Last year the program included Alberto Cavalcanti’s Went the Day Well?, which he directed for Ealing Studios in 1942. Partly out of a sense of duty, since I cover Great Britain for the textbook, I went to the screening. It turned out to be a well-made, engaging, and surprisingly affecting film.

Alberto De-Almeida Cavalcanti

Alberto Cavalcanti is one of those names that people who take courses in film tend to be vaguely aware of, and that for only a handful of titles. He got his start as a set designer on Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine (1923). His first film as a director, the 1926 experimental city symphony Rien que les heures, is a minor classic of the era. Coal Face (1935) is one of the better known British documentaries of the 1930s. Cavalcanti worked for Ealing for several years in the 1940s, and a modern cinema buff is likely to know his two episodes of the collectively directed Dead of Night (1945), including “The Ventriloquist’s Dummy,” the most highly regarded of the batch. Devotees of Ealing or of classic British comedy will also be familiar with his Champagne Charlie (1944). His other best-known films are Nicholas Nickleby and They Made Me a Fugitive (both 1947).

In an era of globilization, Cavalcanti’s career looks positively modern. Born in Rio De Janeiro, he made his early films in Paris. He worked in British documentaries during the 1930s before moving to Ealing, and he remained in England throughout the 1940s. The rest of Cavalcanti’s filmmaking career saw him on the move, including projects in East Germany, Israel, and Brazil. He had a brief stint in TV in the early 1970s before he retired. He died in Paris in 1982. He tended to sign his films simply “Cavalcanti,” as is the case on Went the Day Well?

British Pluck

Based on Graham Greene’s short story, “The Lieutenant Died Last,” Went the Day Well? is a “what if?” tale. A group of Germans disguised as British soldiers deceive a small village’s citizens into letting them billet there and conduct practice exercises. In reality they are there to set up observation posts in preparation for an invasion.

When the film was being planned, there were many rumors in England that a German invasion was imminent and much speculation as to whether the country could resist such a thing successfully. The film has no doubts. In fact, its brief frame story is set in 1945, and the narrator, one of the inhabitants of the fictional village Bramley End, reveals that Germany has been defeated. The narrator shows us the grave of several German soldiers who died in the attempted infiltration.

From the start, then, the spectator is aware that the apparent British soldiers who arrive in Bramley End are disguised Germans and that they will be defeated. This seems like an odd tactic, letting us know so much, and yet it makes perfect sense. The point of the early part of the film is to introduce us to the villagers who will form the collective hero of the plot. Seeing them going about helping British soldiers settle into the local hall and various households would hardly be dramatic. As it is, knowing more than they do, we are in suspense as to whether and how they will discover the truth and react.

From the start, then, the spectator is aware that the apparent British soldiers who arrive in Bramley End are disguised Germans and that they will be defeated. This seems like an odd tactic, letting us know so much, and yet it makes perfect sense. The point of the early part of the film is to introduce us to the villagers who will form the collective hero of the plot. Seeing them going about helping British soldiers settle into the local hall and various households would hardly be dramatic. As it is, knowing more than they do, we are in suspense as to whether and how they will discover the truth and react.

At first they seem the conventional characters of a comedy or light drama—the sorts who would be the supporting roles in a Hitchcock film like The Lady Vanishes. They innocently cooperate in typical British fashion, giving directions and offering tea and spare bedrooms. The initial third or so of the film is pleasant in tone, despite our underlying awareness of the enemy being let into these people’s midst.

Yet the little scenes of ordinary life swiftly and subtly set up the traits in these people that will allow them to fight back later. The local shopkeeper and telephone operator may be a bit dotty and forgetful, but she also bridles when one of  the Germans manhandles a boy who had been snooping around the equipment in the soldiers’ truck. In the same scene, that boy is established as spunky and curious. Went the Day Well? manages to set up several major characters that we come to care about, as well as many recognizable supporting figures. There is no one protagonist. In fact, the film’s top-billed actor, Leslie Banks (familiar to modern audiences mainly from The Most Dangerous Game, the original Man Who Knew Too Much, and Henry V), is a traitor, secretly aiding the Germans. That’s Banks in the photo surmounting this entry.

the Germans manhandles a boy who had been snooping around the equipment in the soldiers’ truck. In the same scene, that boy is established as spunky and curious. Went the Day Well? manages to set up several major characters that we come to care about, as well as many recognizable supporting figures. There is no one protagonist. In fact, the film’s top-billed actor, Leslie Banks (familiar to modern audiences mainly from The Most Dangerous Game, the original Man Who Knew Too Much, and Henry V), is a traitor, secretly aiding the Germans. That’s Banks in the photo surmounting this entry.

Naturally once the villagers discover who their guests really are, they come through with English pluck and resourcefulness–the women as well as the men. The film doesn’t sugar-coat the conflict, though. A number of characters one would not conventionally expect to die do meet heroic ends, and the tone rapidly turns more serious roughly halfway through the action.

Went the Day Well? is a handsome film, too. British films of the 1930s sometimes look like low-budget Hollywood imitations, but by the 1940s the studios had more resources. Cavalcanti’s design sense serves him well, and the beautifully lit scenes and crisp editing look like something MGM could have been proud of. William Walton contributes a brief but suitably grand score.

Went the Day Well? is a handsome film, too. British films of the 1930s sometimes look like low-budget Hollywood imitations, but by the 1940s the studios had more resources. Cavalcanti’s design sense serves him well, and the beautifully lit scenes and crisp editing look like something MGM could have been proud of. William Walton contributes a brief but suitably grand score.

Sources

Unfortunately Cavalcanti’s films aren’t easily available on DVD in the U.S. The only current way to buy Went the Day Well? on region 1 DVD is as part of a set, the “British War Collection.” (The set was originally released as individual discs as well, and several copies of that edition of Went the Day Well? are offered on eBay.) Amazingly, the only other in-print films are Le Capitaine Fracasse (a re-discovered 1929 French film with a young Charles Boyer, co-directed by Cavalcanti), Nicholas Nickleby, and They Made Me a Fugitive.

Those with multi-region players can visit Amazon.uk, where one can find Went the Day Well?, the three films just listed, Dead of Night, and Champagne Charlie.

Went the Day Well? seems like the kind of film ripe for a Criterion edition, if we may drop a hint in their ear.

Added May 11:

David Cairns, director and scriptwriter, critic and blogger, and Cavalcanti fan has responded to this entry with one of his own, discussing other aspects of Went the Day Well? (Beware, his entry has more SPOILERS than mine.) As he rightly points out, the early portions of the film not only set up the bucolic village and its apparently conventional British country folk, but they provide an object lesson for citizens not to behave in such a naive and unquestioning fashion. Germans might be anywhere! I was mainly writing about the narrative conventions that would hold for a modern audience watching a decades-old classic. There’s no doubt, though, that for a contemporary audience there would have been that implication. The point is fairly explicitly made when one character finally finds a clue that makes her begin to suspect something is wrong, while another dismisses her ideas–with we all the while knowing that the woman who becomes suspicious is right.

I don’t think I buy another claim David makes about a subtext for the film: “the film becomes more subversive. According to Cavalcanti, a pacifist, his objective was to show that when war comes to even a place as charming as Bramley End, the people become monsters. Without the slightest change in underlying personality, peace-loving and jocular countryfolk pick up weapons and set about slaughtering their fellow humans.”

I don’t find the villagers in any way to be monsters, even in their most violent acts against the invaders. For one thing, it’s self-defense in wartime. The starkly violent scene of the Germans ambushing and mowing down a group of men from the Home Guard makes that clear from before the point when the villagers respond. I certainly can’t believe that the audiences of 1942 would have seen the villagers as descending into some primitively violent instincts. After all, this film came out only a little over a year after the end of the Blitz. In fact, the Germans had attempted to infiltrate England in preparation for the Battle of Britain, which in turn was to culminate in a land invasion. All infiltration attempts were thwarted, and poor intelligence was a major contributing factor to what became Germany’s first significant loss of the war. There would have been few people in Britain who could conceive of pacifism as a response to what they had recently lived through.

For another thing, the villagers don’t kill ruthlessly. All three women who kill someone pause afterward, clearly upset and even nauseated . The men are more blithe about it, but they’re seldom seen killing except in pitched battles, and just as often the village menfolk are the victims up until the rescuing soldiers arrive at the end. I’d argue that the characters’ underlying personalities are assumed to include the courage and determination that surface in time of need.

Thanks to David for his thought-provoking comments and for backing me up in urging that cinephiles should seek out this and other Cavalcanti films. He mentions They Made Me a Fugitive in particular.

DVD reviewer Slarek has reviewed Went the Day Well? on DVD Outsider. (Again, SPOILERS.) Among other interesting comments, he reveals that it was shot in Turville, Oxfordshire. I think Bramley End is probably supposed to lie in the south of England, where most of the German aircraft and the putative invasion would have entered the country. Still, the rolling landscapes and hedgerow-lined fields of Kent and Sussex are fairly similar to those of Oxfordshire. As Slarek proves with a photo, the village is not all that much changed today.

Snapshots and soundbites

Boardman’s Art Theatre, two blocks from the Virginia Theatre, Champaign, Illinois.

DB here:

As you may surmise, a hell of a time was had by all at last week’s Ebertfest. In the sessions I moderated, I was often so busy listening and thinking about my next question that I didn’t have time to write down all the aperçus that spilled forth from the guests. But here are some soundbites, mixed with pix.

Jeff Nichols, director of Shotgun Stories: “I managed to make a 90-minute movie that feels 2 ½ hours long.”

Jeff Nichols, John Peterson (The Real Dirt on Farmer John), Eran Kolirin (The Band’s Visit), Timothy Spall (Hamlet).

Bill Forsyth on his early work: “I made films about teenagers because they were cheap to hire.”

Christine Lahti (Swing Shift, Running on Empty, Jack & Bobby, Amerika) and Bill Forsyth, reunited for the screening of Housekeeping.

Why so much multiframe imagery in Hulk? “In those notes you get from studio people,” Ang Lee explained, “they always want more and faster. So I decided to give it to them.”

Ang Lee (Hulk) and unidentified admirer.

Barry Avrich asked Suzanne Pleshette how she had survived so long in the industry. Suzanne: “I don’t have a gag reflex.”

Barry Avrich (The Last Mogul, Satisfaction, Citizen Cohl: The Untold Story, and the book Selling the Sizzle).

Paul Schrader: Theatrical screening is dead. “The multiplexes look like mortuaries.”

Tom DiCillo: “Going to a film is a religious experience. . . . When you see it on a computer screen, fuck it.”

Tom DiCillo (Delirious) and Timothy Spall.

Paul Schrader: “When I started, there was a crisis of content. Nobody knew what a movie should be about. So we had films with sex and violence and anti-heroes. But now we have a crisis of form. How long should a movie be? How big should the screen be? What is this thing called movies?”

Paul Schrader (Mishima) and Hannah Fisher (Dubai International Film Festival).

“What part of this is directing?” Tom DiCillo, reflecting on the fact that it took six years to set up Delirious and he spent only 25 days behind the camera.

Tarsem Singh: “I’ve been an atheist since I was nine. I’ve never used any intoxicant—drugs or liquor or whatever. But I don’t like to associate with nondrinkers: they’re either religious or reformed alcoholics.”

Mary Corliss (Film Comment) and Richard Corliss (Time).

Joey Pantoliano (The Matrix, Memento, The Sopranos, Canvas, and book Who’s Sorry Now) with unidentified admirer.

Michael Barker (Sony Pictures Classics).

Eiko Ishioka: “When Paul asked me what I thought about Mishima, I said, ‘I don’t like him.’ He said, ‘Perfect!'”

Eiko Ishioka (Mishima, The Cell, The Fall), multimedia artist.

The Ebertfest Team

Chaz Ebert.

Mary Susan Britt.

James Bond, projectionist, and Nate Kohn, Festival Director.

See you here next year? Jim Emerson (scanners, Rogerebert.com) is counting the hours.

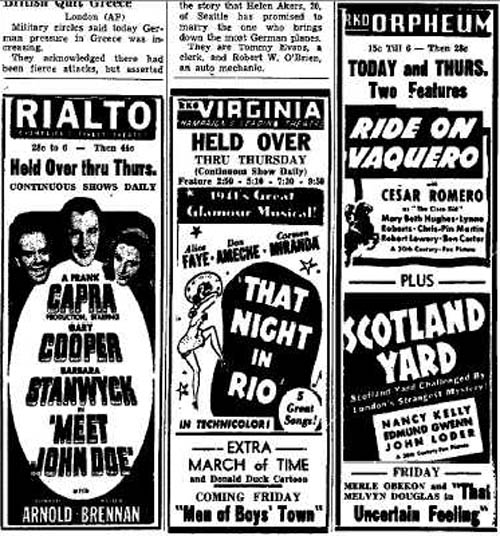

Bonus feature: What you would have been able to see in Urbana-Champaign 16 April 1941.