The magic number 30, give or take 4

Thursday | September 13, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

David here–

When I was teaching, students often came to my office hours with variants of this question. “I want to direct Hollywood movies. When should I start trying to get into the industry?”

My answer usually ran this way:

Your prospects are almost nil. It’s tremendously unlikely that you will become a professional director. You may wind up in some other branch of the industry, though. In any case, start now. Aim for summer internships while you’re in school, and try to get a job in LA immediately after graduation—preferably through a friend, a relative, a relative of a friend, or a friend of a relative.

My answer still seems reasonable, but recently I’ve begun to wonder if it holds up across history. Suppose we refocus our goggles on the macro scale. At what ages do most Hollywood directors make their first feature? If we can come up with a solid answer, it would be one instance in which studying film history can have very practical consequences.

No country for old men

In any field, most people would expect to have their careers moving along by the time they hit their early thirties. But aspiring filmmakers may think that there’s a long period of preparation–working in a mailroom, sweating over screenplays–before they finally get to direct. Directing films is a top-of-the-heap role. Who would trust a young first-timer with a multimillion-dollar investment and authority over far more experienced performers and technicians?

Nearly everybody, actually.

Executives tend to be oldish and not fully aware of what the target movie audience likes. A few years ago a friend of mine, consulting for the studios, went to a meeting of suits and was told that all the new digital sampling and mixing software was purely an effort to steal music. He replied that there were legitimate creative uses of that technology. “For example?” one exec asked. My friend said, “Well, there’s Moby.” Nobody at the table knew who Moby was.

So hiring young people in touch with their peers’ tastes makes sense. Indeed, many of today’s top filmmakers started making features quite young. I haven’t made an exhaustive survey, but picking directors more or less at random yields some pretty interesting results.

Note: It’s hard to know how long a movie took to make, so I’ll use the release date as my benchmark. With the exceptions noted at the end, I haven’t checked people’s birthdays against day and month release dates. As a result, the ages of directors that I’ll be giving fall within a year of the releases. That works well enough to establish an approximate age range for a general tendency. And since it takes at least a year to get a project finished and released, we have to remember that most of these people started work on their first feature quite a bit earlier than is indicated by the age I give.

Start with directors who broke through in the 1990s and 2000s. Many were about 30 when their first features came out: Keenen Ivory Wyans (above; I’m Gonna Get You Sucka), Michael Bay (Bad Boys), David Fincher (Alien 3), and Spike Jonze (Being John Malkovich). A tad older at their debuts were Alex Proyas at 31 (The Crow), Cameron Crowe at 32 (Say Anything), James Mangold at 32 (Heavy), Karyn Kusuma at 32 (Girlfight), McG at 32 (Charlie’s Angels), David Koepp at 33 (The Trigger Effect), Allison Anders at 33 (Border Radio), and Mark Neveldine at 33 (Crank).

Actually these are the older entrants. A great many current directors completed their first feature in their twenties. Quentin Tarantino, Reginald Hudlin, Roger Avary, and Joe Carnahan debuted at 29, Sofia Coppola and Brett Ratner at 28, Peter Jackson and F. Gary Gray at 26.

Go a little further past 33 and you’ll find a few big names like Alexander Payne (35), Nicole Holofcenter (36), Simon West (36), and Ang Lee (38). Almost no contemporary directors broke into the game past 40. The most striking case I found is Mimi Leder, who signed The Peacemaker when she was 45.

On the whole, the directors who start old have found fame and power playing other roles. When you’re David Mamet, you can tackle your first feature at 40. (He’s my age; don’t think this doesn’t make me depressed.) If you’re a producer like Bob Shaye or Jon Avnet, you can start directing in your fifties. Actors, especially stars, get a pass at any age. Mel Gibson made his first feature at 37, Steve Buscemi at 39, Barbra Streisand at 41, Anthony Hopkins at 59.

Putting aside such heavyweights, the lesson seems to be this. In today’s Hollywood, a novice director is likely to start making features between ages 26 and 34. It’s also very likely that he or she will have already done professional directing in commercials, music videos, or episodic TV, as many of my samples did.

But what about the Movie Brats?

Is today’s youth boom a new development? The Baby Boomers will yelp, “No! Everybody knows that we invented the director-prodigy.” Look:

*Dementia 13: Francis Ford Coppola, 24. If you don’t want to count that, You’re a Big Boy Now was released when Coppola was 27.

*Who’s That Knocking at My Door?: Martin Scorsese, 25.

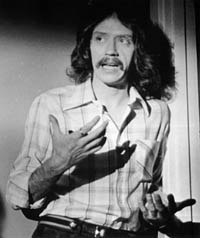

*Dark Star: John Carpenter (above), 26.

*THX 1138: George Lucas, 27.

*Night of the Living Dead: George Romero, 28.

*The Sugarland Express: Steven Spielberg, 28. If you count the TV feature Duel, subtract 2 years.

*Targets: Peter Bogdanovich, 29.

*Dillinger: John Milius, 29.

*Blue Collar: Paul Schrader, 32.

*Good Times (with Sonny and Cher): William Friedkin, 32.

*Easy Rider: Dennis Hopper, 33.

True, the 70s also revved up veterans like Altman and Ashby, but it was the new generation, we’re always told, who made the difference. Hollywood was run by old men who had brought the studio system to the brink of ruin. The twentysomethings smashed the barricades and made a place for young filmmakers.

It might have seemed that way at the time, but the belief was probably due to a quirk of history. The 1960s and early 1970s were in one respect a unique period in the history of American cinema. During those years, the studios had the widest range of age and experience ever assembled. For the first time in history, it looked like a retirement home.

Look at it this way. In the 1960s, films were being made by directors who had started in the 1950s (e.g., Arthur Penn, Sidney Lumet), as you’d expect. But at the same time there were films by directors who had started in the 1940s: Fred Zinneman, Sam Fuller, Robert Aldrich, Anthony Mann, Nicholas Ray, Vincente Minnelli, Robert Rossen, Robert Wise, Mark Robson, and many others. Furthermore, some of the biggest names of the 1960s were directors who had started in the 1930s, like George Cukor, Carol Reed, George Stevens, Otto Preminger, and Joseph Mankiewicz. More remarkably, the 1960s saw the release of films by masters who had begun in the 1920s, notably Hitchcock, Hawks, Capra, and Wyler.

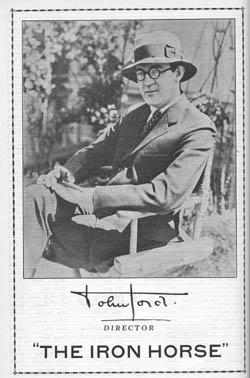

And believe it or not, several directors who had begun in the 1910s were still active nearly fifty years later. John Ford is the most obvious case, but Chaplin, Alan Dwan, Henry King, Fritz Lang, George Marshall, and Raoul Walsh signed films in the 1960s. When Sidney Lumet celebrates a half-century of directing with the upcoming release of Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, he will be considered a rare bird in today’s cinema; but in a broader historical context he doesn’t stand alone.

Interestingly, the arrival of the Movie Brats and the blockbuster brought nearly all the veterans’ careers to a halt. No matter what decade an old-timer started, by the mid-1970s he was most likely dead, retired, or making flops. Perhaps the Movie Brats’ sense of Hollywood as a haunted house was created in part by the felt presence of six decades of history.

The studio years

But what about those codgers? At what age did they get started? A look at the evidence suggests that the rise of the twentysomething Movie Brats has plenty of precedents.

The Hollywood studios ran a sort of apprentice system. In the 1920s and 1930s, short comedies and dramas were the era’s equivalent of music videos and commercials—ephemeral material that allowed youngsters to learn their craft. For example, George Stevens started as a cameraman, and at age 26 graduated to directing short comedies. Three years later he made his first feature (The Cohens and Kellys in Trouble, 1933).

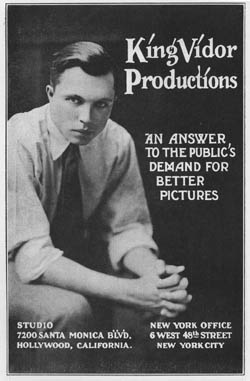

Stevens wasn’t atypical. In the 1920s and 1930s, major directors seem to have started as young as they do now. King Vidor began in features at 25, Rouben Mamoulian at 26. Mervyn LeRoy’s first feature was released when he was 27, the same age that Keaton, Capra, and Sam Taylor entered the field. Byron Haskin and W. S. Van Dyke made their debuts at 28. Hawks started at 30, as did Victor Fleming, Lewis Milestone, and Joseph H. Lewis. Clarence Brown signed his first solo feature at 31, the same age as Jules Dassin and George Cukor at their debuts.

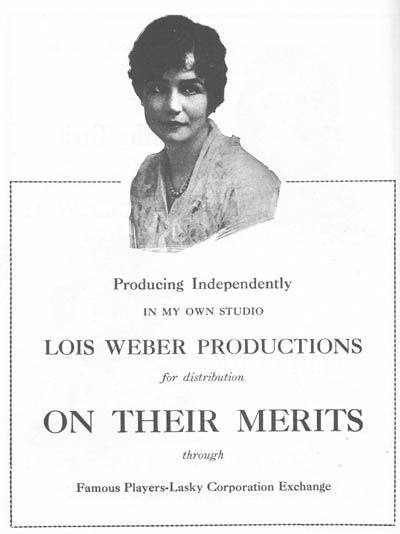

Even more remarkable is what went on during the 1910s. As Hollywood was becoming a film capital, it became a playground for twentysomethings. Lois Weber, Alan Dwan (who may have directed 400 movies), James Cruze, Reginald Barker, George Marshall, George Fitzmaurice, Raoul Walsh, and many others directed their first features before they were thirty. (At this point, a feature film could be around an hour. Kristin explains here.) Cecil B. DeMille was on the senior side, having directed The Squaw Man (1914) at age 33. Griffith was then even older of course, but having started in 1908, somewhat earlier than this generation, his authority waned as theirs rose. And he had started directing within my golden zone, at age 33.

Why so many youngsters? In the 1910s, the industry was growing rapidly and it needed a lot of labor. Few people went to college, so teenagers could take low-level jobs at the studios straight out of high school, or even without a secondary education. Moreover, Kristin reminds me that at this time life expectancy was much lower than today; in 1915 a white male on average would live only 53 years. Beginners hurried to get started, and bosses probably found comparatively few oldsters around.

At the other extreme, the World War II years seem to have been a tough time to break in. Anthony Mann, Nicholas Ray, Don Siegel, Richard Brooks, Robert Aldrich, Robert Rossen, and other gifted directors had to wait until their mid- to late thirties before taking the director’s chair in the second half of the 1940s. The 1950s somewhat put the premium on youth again with fresh blood, especially from the East Coast. The most famous instances are Stanley Kubrick (Hollywood feature debut at 28), John Frankenheimer (debut at 30), and John Cassavetes (Hollywood debut at 32).

In short, Hollywood has always favored fresh-faced novices. It’s not surprising. Young people will work exceptionally hard for little pay. They have reserves of energy to cope with a milieu dominated by deadlines, delays, long hours, and rough justice. They are more or less idealistic, which allows them to be exploited but which also infuses the creative process with some imagination and daring. The executives need wisdom, but the talent needs, as they say, a vision.

Some last questions

Of course in every era a few older hands start directing features comparatively late. Lloyd Bacon, auteur of the masterpiece Footlight Parade, didn’t make a feature (Broken Hearts of Hollywood, 1926) until he was thirty-seven, after dozens of shorts. Daniel Petrie was forty when his 1960 feature The Bramble Bush was released, and Julie Dash was forty when Daughters of the Dust came out. But you have to look hard to find careers starting this late. Most of the evidence I’ve seen indicates that first features skew young.

First question, then: Is the tendency to seize talent young unique to Hollywood, or is it a characteristic of other popular film industries? My hunch is that it has been a worldwide phenomenon. Eisenstein, who was 27 when he made Potemkin, was treated the oldest of his cohort of Soviet directors; at the other end of that scale were Gregori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg, who collaborated on their first film when they were 19! In Japan, Ozu, Mizoguchi, and Kurosawa started directing in their twenties. Michael Curtiz was 30 when he made his first feature, which happened to be Hungary’s first as well. The very name of the French New Wave was borrowed from a sociologist’s catchphrase for postwar twentysomethings. Today, in Europe or Asia, most beginning directors are in their mid-to-late twenties or early thirties. I suspect that everywhere the film industry gobbles up youth, both in front of and behind the camera.

Second, a question for further research. Hollywood hires a lot of first-timers, but how many of them build long-lasting careers? It’s sometimes said that it’s easier to get a first feature than a second.

Third, who’s the youngest director to make a Hollywood feature? The most famous candidate for the Early Admissions program is Orson Welles, who was 25 when Citizen Kane premiered. But on this score at least his old rival William Wyler had him beat. Wyler was 24 when he released his first feature. The fact that his mother was a cousin of Carl Laemmle, boss of Universal, doubtless helped him start near the top.

So is Wyler, at 24, the winner? No. John Ford, Ron Howard, and Harmony Korine were 23 when their first features opened. But wait: Leo McCarey was only 22 when his first feature (Society Secrets) was released in 1921. M. Knight Shyamalan’s first first feature, Praying with Anger, achieved a limited release in 1993, when he was 22.

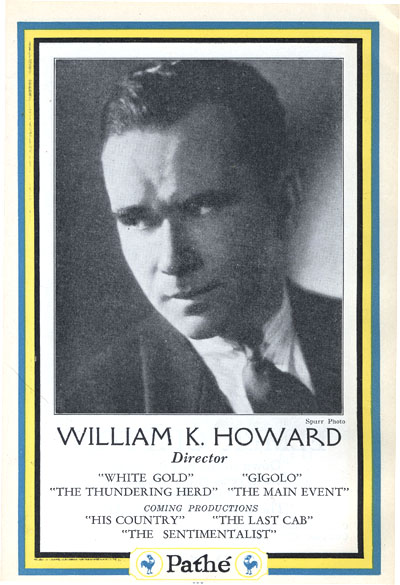

Yet I think that William K. Howard has the edge. Born on 16 June 1899, he signed two features in late 1921, when he was 22, putting him abreast of McCarey and Shyamalan. But Howard also co-directed a feature that was released on 22 May 1921—about three weeks before his twenty-second birthday. Brett and Sofia and PJ, you are so over the hill.

(Once we move out of the US, the clear winner would seem to be Hana Makhmalbaf. When she was ten, she served as AD for her sister Samira on The Apple, and she signed a documentary feature when she was fifteen. “I used to get excited over the words sound, camera, action. There was a strange power in these three words. That’s why I quit elementary school after second grade at age eight.”)

Finally, how does a little knowledge of film history help us steer hopefuls on the road to Hollywood? It gives us a sharper sense of timing and opportunity. My best revised answer would be this.

Start as young as you can, in any capacity. For directing music videos and commercials, the window opens around age 23. For features, the best you can hope for is to start in your late twenties. But the window closes too. If you haven’t directed a feature-length Hollywood picture by the time you’re 35, you probably never will.

Unless your last name is Bruckheimer, Bullock, Kidman, Cruise, or Bale.

PS 16 Sept 2007: Some corrections and updates: I’m not surprised that my more or less random sampling missed some things. So I’m happy to say that we have new contenders in the youth category.

Charles Coleman, Film Program Director at Facets in Chicago, pointed out that Matty Rich was only 19 when Straight Out of Brooklyn was released in 1991. So my candidate, William K. Howard, is second-best at best.

As for Hana Makhmalbaf, she’s been beaten too. Alert reader Ben Dooley wrote to tell me of Kishan Shrikanth, who was evidently ten years old at the release of his feature, Care of Footpath, a Kannada film featuring several Indian stars. Kishan, a movie actor from the age of four, has been dubbed the world’s youngest feature film director by the Guinness Book of World Records. You can read about him here, and this is an interview.

As for Hana Makhmalbaf, she’s been beaten too. Alert reader Ben Dooley wrote to tell me of Kishan Shrikanth, who was evidently ten years old at the release of his feature, Care of Footpath, a Kannada film featuring several Indian stars. Kishan, a movie actor from the age of four, has been dubbed the world’s youngest feature film director by the Guinness Book of World Records. You can read about him here, and this is an interview.

From Australia, critic Adrian Martin writes to point out that Alex Proyas made features before The Crow. “A clear case of Hollywood/ Americanist bias!! (Just kidding.) Proyas had an extensive career in Australia before the USA, and that includes his first, intriguing feature, Spirits of the Air, Gremlins of the Clouds, in 1989. Which puts him around 27 at the time!”

Finally (but what is final in a discussion like this?) over at Mark Mayerson’s informative animation blog, there’s a discussion about animation directors, who tend to be quite a bit older when they sign their first full-length effort. Mark’s reflections and the comments point up some differences between career opportunities in live-action and animated features.

PPS 27 December 2007: Malcolm Mays, currently 17 years old, is shooting a feature under studio auspices. Read the inspiring story here.