The adolescent window

Saturday | November 17, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Last month I visited the University of Texas at Austin. I had a great time, with wonderful people and conversation. The food was tasty too. There was a lot of talk, and one question in particular set me thinking.

In his Film History seminar, Professor Charles Ramirez Berg asked me what movie made me decide to study film. Before I knew what I was saying, I admitted that unlike most people who write about movies, no single movie, nor even a handful of movies, pushed me in this direction. I had no cinematic epiphany.

Nor did I have the sort of childhood that seems archetypal for film geeks. You know the tale. I grew up in New York/ Chicago/ LA and went to the movies every day, sometimes twice or more. I practically lived at the [insert colorful but rundown movie house here]. When I wasn’t at the movies I was watching little-known film noirs/ Monograms/ Budd Boettichers on TV into the night. By the time I could vote, I’d seen thousands of movies, and King Kong at least five times.

This wasn’t me. I grew up on a farm. I saw at most one or two movies a week on those Saturday afternoons when my family went to the town ten miles away. I saw what every kid saw—Disney, Martin and Lewis, Francis the Talking Mule. I did sometimes watch Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto movies on the couple of TV channels we could pull in, but I didn’t saturate myself. About age thirteen I started to get interested in film by reading about it, in books like Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art and Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now. These were my guides to what to watch on TV. So yes, I did stay up late occasionally, but to see bona fide classics like Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons. The joys of Joseph H. Lewis and Robert Siodmak had to wait until in 1963 my hands closed around the Film Culture issue devoted to Andrew Sarris’ American Directors survey.

So I became a film wonk through years of accretion, gradually seeing more and more in high school (once I could drive a car) and college (running the film society) and then deciding to go to graduate school.

But I did find an answer to Charles’ question. I said that my childhood was far more steeped in TV and radio than in movies. Afterward I realized that certain books and magazines had a big influence on me as well.

What follows may seem narcissistic nostalgia, but I do have a general point. It’s the Law of the Adolescent Window:

Between the ages of 13 and 18, a window opens for each of us. The cultural pastimes that attract us then, the ones we find ourselves drawn to and even obsessive about, will always have a powerful hold. We may broaden our tastes as we grow out of those years—we should, anyhow—but the sports, hobbies, books, TV, movies, and music that we loved then we will always love.

The corollary is the Law of the Midlife/ Latelife Return:

As we age, and especially after we hit 40, we find it worthwhile to return to the adolescent window. Despite all the changes you’ve undergone, those things are usually as enjoyable as they were then. You may even see more in them than you realized was there. Just as important, you start to realize how the ways you passed your idle hours shaped your view of the world—the way you think and feel, important parts of your very identity.

Let me get specific.

The view from my window

Jean Shepherd. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah.

I was born in 1947 and graduated from high school in 1965. What was my angle of view onto the pop-culture landscape in 1960-1965?

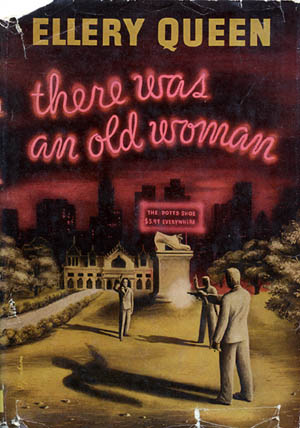

Reading: I read a lot of classic and contemporary American literature, especially Twain and Faulkner. Also a lot of nonfiction, especially Barzun, Orwell, and Kenneth Burke. But more eagerly I soaked up detective stories. Not the hardboiled ones, though I loved Hammett’s Red Harvest. My favorites were Sherlock Holmes, Wilkie Collins, and the Golden Age classics: Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, John Dickson Carr/ Carter Dickson, Ellery Queen, and Rex Stout. I now realize that from these skilful storytellers I was absorbing lessons in narrative construction, as well as a taste for artifice.

More specifically, I was learning something I could only much later make explicit: Popular culture undertakes formal experimentation as intriguing as anything in the official avant-garde. Ellery Queen’s openly fabulist novels take a central motif—a nursery rhyme, a pun, the Ten Commandments—and then show how it informs action, character psychology, even chapter breaks. John Dickson Carr’s books are like conjuring tricks, with the magician brandishing the clues and steering you away from the trap doors and collapsable top hats. Who else but Carr would call a novel The Reader Is Warned? Among the moderns, perhaps only Ed McBain has the Golden Age flair for creating a multilayered plot based on a central image like ice or a wedge, and he does it within the frame of the most purportedly realistic mode, the police procedural.

Or take a book I’ve probably read twenty times, Anthony Berkeley’s The Poisoned Chocolates Case (1929). Six eminent lawyers, writers, and amateur sleuths have formed a club, the Crimes Circle. They’re presented with a current murder case and challenged to crack it. At six nights of Circle meetings, each one fields a solution, only to have it shot down. Sort of a grad seminar in homicide.

Admirers of film noir and the hardboiled school, who are in the majority now, would complain that this is just the sort of airless exercise that turned the detective story into a crossword puzzle. Yet there is tension whenever we play off competing answers to a question; anyone who thinks that empirical reasoning is bloodless should read a scientist’s biography. Out of a handful of clues and three or four suspects, The Poisoned Chocolates Case conjures up six detailed but mutually exclusive solutions. At the end, there’s a purely aesthetic pleasure in watching the puzzle snap into a surprising whole that integrates aspects of all the failed answers. As a cherry on the sundae, we’re rewarded with one of the niftiest last lines in crime fiction: “Nobody enlightened him.”

My tastes in the genre have broadened. Now I read and reread Le Carré, Rendell, Hillerman, Westlake/ Stark, Bloch, and the procedurals, especially Rankin. Of course I like Highsmith and Elmore Leonard. Robert Barnard and Peter Dickinson can sometimes evoke Golden Age knottiness. But when I want formal highjinks, I pack a classic in my carry-on and I’m seldom disappointed.

On the Austin trip it was Stout’s The Rubber Band, an elegant adventure of Archie Goodwin and Nero Wolfe.

I’ve registered my admiration for Stout elsewhere on this blog; I consider him one of the great masters of American vernacular prose. The Rubber Band is one of his best, and not just because every page boasts at least one of Archie’s irresistible sentences about Wolfe.

I’ve registered my admiration for Stout elsewhere on this blog; I consider him one of the great masters of American vernacular prose. The Rubber Band is one of his best, and not just because every page boasts at least one of Archie’s irresistible sentences about Wolfe.

Since he only went outdoors for things like earthquakes and holocausts, he was rarely guilty of movement except when he was up on the roof with Horstmann and the orchids, from nine to eleven in the morning and four to six in the afternoon, and there was no provision there for pole vaulting.

That’s writing.

TV, I now realize, tutored me further in the unbridled audacity of popular culture. Granted, in certain circles I’ve been known to say unenthusiastic things about TV. Nowadays I don’t watch anything but The Simpsons and Keith Olbermann. But who can deny the past? I’m a creature of the box.

My parents got TV early, in the early 1950s, and my sisters and I spent many a winter afternoon in front of cartoons, the Disney show, and Roy Rogers. But I didn’t like the official hits, like Gunsmoke and Bonanza. As I got older, I was snagged by grownup shows like Jackie Cooper’s Hennessey and the short-lived It’s a Man’s World. Why? I don’t know. Perhaps they showed how badinage could mingle with serious drama. No mystery about Ernie Kovacs, though, whose nuttiness delighted me in the way that Monty Python would capture the kids of the 1970s. And like everybody else, I was haunted by a weekly visit to the Twilight Zone.

But above all stood George and Gracie. When I started to get what they were about, their program was ripening into its baroque phase. More than individual shows, I remember the brilliant central conceit. Gracie would hatch a wacko scheme, usually recruiting the hapless Harry von Zell as her minion. George would get suspicious and retire to his den to tune in the very show we were watching. He was then in a position to block her maneuvers, usually by tormenting von Zell. The idea that George could simply watch his own program still seems a stroke of genius. Artistic form, I must have realized subconsciously, can always be turned into a dizzy game. M. Godard, Ozu-san, meet Burns and Allen.

But above all stood George and Gracie. When I started to get what they were about, their program was ripening into its baroque phase. More than individual shows, I remember the brilliant central conceit. Gracie would hatch a wacko scheme, usually recruiting the hapless Harry von Zell as her minion. George would get suspicious and retire to his den to tune in the very show we were watching. He was then in a position to block her maneuvers, usually by tormenting von Zell. The idea that George could simply watch his own program still seems a stroke of genius. Artistic form, I must have realized subconsciously, can always be turned into a dizzy game. M. Godard, Ozu-san, meet Burns and Allen.

The radio was constantly on in our house, with my mother listening to Arthur Godfrey or Art Linkletter. These geezers were intolerable to my teenage tastes. Give me my two main sources of aural pleasure: WKBW radio and Jean Shepherd.

WKBW was a radio station out of Buffalo. At 50,000 watts it was so powerful it tended to seep into any blank spot on the dial. Actually, the DJs probably didn’t need an antenna, since they conducted their shows at ear-splitting volume. They indulged in all the profound things that characterized radio in the 1950s: cute sound effects (car crashes, always good), music clips (audio tape made it easy), jingles and station IDs that quickly became earworms, and nonstop patter sustained by whinnies, table-pounding, and laughter at feeble jokes. KB’s promotional efforts were no less strenuous. Once the station asked the public’s help in finding a missing DJ, only to reveal that he’d gone into hiding to drum up publicity.

WKBW was a radio station out of Buffalo. At 50,000 watts it was so powerful it tended to seep into any blank spot on the dial. Actually, the DJs probably didn’t need an antenna, since they conducted their shows at ear-splitting volume. They indulged in all the profound things that characterized radio in the 1950s: cute sound effects (car crashes, always good), music clips (audio tape made it easy), jingles and station IDs that quickly became earworms, and nonstop patter sustained by whinnies, table-pounding, and laughter at feeble jokes. KB’s promotional efforts were no less strenuous. Once the station asked the public’s help in finding a missing DJ, only to reveal that he’d gone into hiding to drum up publicity.

In my day, the loudest mouth belonged to Joey Reynolds, who brayed over records and satirized rock and roll with an appalling ditty called “Rats in My Room.” When he was fired, he nailed his shoes to his boss’s door, adding a note: “Fill These.” I was happy to learn that this piece of teenage lore seems to be true, or at least so a fanatical WKBW website indicates. Joey continues on the airwaves, albeit more sedately.

Speaking of music, KB opened the adolescent window to the tunes that still move me. I was too young to like Elvis and had an affectionate but distant relation to the Beatles. My favorites came mostly from what I’ve learned to call the Brill Building sound. On 24 December every year, Kristin folds her arms in weary patience as the Drifters, Gene Pitney, Connie Francis, and Paul Anka pour forth into our living room.

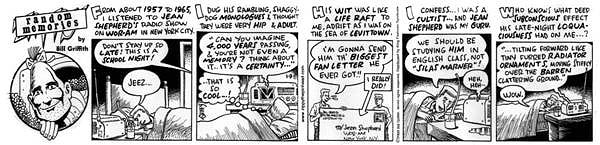

Jean Shepherd was a wholly different story. The WOR signal couldn’t creep into upstate New York by day, so my bedside tube radio crackled and hissed as 11:15 p. m. approached. Would the signal pull through? It usually did. In fact it seemed to get stronger as, lying in the dark, I heard the familiar trumpet call and galloping music that announced Shep’s show. Another difference from Top 40: Here was an adult talking to a kid as if I were an adult. And an adult who lived in Manhattan! I discovered then that the media aim downward, age-wise: a teenage TV show is actually watched by pre-teens, a college show (like Shep’s) appeals most to highschoolers (like me).

Shep was one of the pioneers of long-form talk radio. He didn’t take phone calls and he seldom had guests. He claimed to be a social commentator, and he did point out the foibles of contemporary media and society. Mostly, though, he was a yarn spinner in the Twain tradition. As he told stories from his life, especially his childhood in Indiana, digressions would split off unexpectedly. Somehow, though, everything wound back to make a point–usually about the vainglory of being human. What made the stories fascinating was not only the delivery (poetic turns of phrase, a smooth, earnest voice that could sink to an urgent whisper) but their fundamental ordinariness. He told of midwestern air shows, enamel table tops, summer baseball, and disastrous Valentine’s Day parties. He celebrated the commonplace and advised his listeners to simply watch everything closely, to find the poetry and absurdity that pervade our lives. I think that my sense of humor owes a lot to him. Perhaps also my tendency to yakkiness.

Shepherd is best-known today for A Christmas Story, the movie based on some of his stories. If you’ve seen it, you’ve heard his unique voice as the narrator. But I first heard the tales of the BB gun and the Old Man’s fetishistic leg-lamp while hunched under the blankets, long after my family had gone to sleep, and Shep’s words put a movie in my head. After my nightly WOR adventures, Garrison Keillor seemed labored and condescending.

From Eugene Bergmann’s capacious book on Shepherd (1), I realize that my nighttime communion with this adult voice was shared by thousands of other kids. He fused the nonconformist sensibility of the Beats and the Hips with a Midwestern distaste for airs and pomposity. He called his fans the Night People. The enemies were the Meatballs, the Slobs, or, in a reference to a Pepsi tagline, the Sociables. He spurred his listeners to send Cassavetes money to fund Shadows; a credit to the Night People appears on the movie. Shep’s motto was “Excelsior” (sometimes, “Excelsior, you fathead”), which encapsulated both his optimism (onward and upward, keep striving) and his fatalism (remember the boy with the banner lying frozen in the snow).

Urged on by Bergmann’s book, I recently discovered a wonderful Shepherd website and a vast podcast vault of his shows, which are also available free on iTunes. (2) Broadcast a little before I started listening, the 1960 “Molded Food” episode was a great iPod companion as I wandered around the UT—Austin campus.

Put not aside childish things

I could mention more items seen through my window, such as the Village Voice, Esquire, and, inevitably, Mad magazine. But the moral should be clear. Whatever called out to you when your window opened—Grease, Patti Smith, Buckaroo Banzai, Sassy, David Bowie, Columbo, Godspell, Lord of the Rings (the book), Penn and Teller, National Lampoon, Pavement, John Hughes movies, Kurt Vonnegut, the B-52s, Earth Girls Are Easy, Beat Street, Master of Puppets, Boondock Saints, Sam Kinison, They Might Be Giants, you name it—is likely to retain its bright purity throughout your days. What’s kitsch or cheesy or retro to others is precious to you.

Make no apologies. It’s not mere nostalgia or guilty pleasure to revisit these creations. You can return to them as to old friends. Encountering them again, you remember when you took it for granted that anything was possible in your life. Their sharp, shining lines fitted your range of vision, and mostly they still do.

Your taste was unerring. These teenage passions represent a big chunk of the finest part of you. In some secret place you are still as uncomplicated as you were then.

(1) Eugene B. Bergmann, Excelsior, You Fathead! The Art and Enigma of Jean Shepherd (New York: Applause, 2005).

(2) In the iTunes store, go to “The Brass Figlagee” under Podcasts.

Thanks to Jeff Smith, Jonah Horwitz, and Dan Morgan for suggesting some things they saw through their adolescent window.

Zippy the Pinhead, by Bill Griffith.