New media and old storytelling

Sunday | May 13, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

DB asks: To what extent has the DVD changed viewing habits and movie storytelling?

As everybody knows, a DVD offers more interactivity than a movie you watch in a multiplex. In a theatre, the movie rolls on, unaffected by anything you may do. But with a DVD you can pause the film, run fast forward, skip to a particular second, shuffle chapters, even play the thing in reverse.

Most minimally, the DVD offers greater convenience. You can halt the film so you can answer a phone call or zip back to replay a bit you might have missed. But some of us wonder if this new interactivity harbors more radical implications. Does the new flexibility of use allow us to experience the film in new ways?

In a mystery film, say there’s a clue at the half-hour mark. In a theatrical screening, we’re pressed forward with no time to ponder it. Watching the film on DVD lets us halt the film, ponder the clue as long as we like, and maybe track patiently back to earlier scenes to test our suspicions about what that clue means. Or suppose you decide to sample the film, browsing through the opening bits of several chapters? More radically, suppose we decide to watch the DVD in reverse? Nothing stops us, and we’d have an experience of the story very different from that of someone who watched the film in the normal order. Doesn’t this all suggest that it’s hard to generalize about what the “ordinary” viewer’s experience of a movie might be nowadays?

Now consider the craft of fictional filmmaking. The movie’s creators make choices about what story information to impart, when to impart it, and how to impart it. They assume that the viewer follows the story in the order mandated by theatrical projection, scene 1, then 2, 3 and onward. Likewise, the pace of uptake is set by the film—no slowing down or speeding up at the viewer’s will. But given the new conditions of digital consumption, these assumptions may be wrong. So shouldn’t the filmmakers take those conditions into account? And more specifically, haven’t some filmmakers already taken them into account? In other words, hasn’t the DVD transformed cinematic storytelling?

This question is important to me. I’ve long argued, along with Kristin, that mainstream US filmmaking, dubbed long ago “classical Hollywood cinema,” has cultivated a sturdy and pervasive tradition of storytelling. (1) That tradition depends on clearly defined characters pursuing well-defined goals. This commitment in turn creates a plot that displays linear cause and effect: In pursuing goals, the protagonist makes one thing happen, and that makes something else happen, which in turn triggers something else. Moreover, the mainstream tradition lays these actions and reactions along a fairly rigid structural layout. And this tradition depends on a system of narration that constantly reiterates the characters’ traits, their goals, important motifs, and the overall circumstances of the action. This is a fairly abstract description, I know; go to my analysis of Mission: Impossible III for a specific example of how the system can work.

But now home video allows our consumption to be highly nonlinear. By skipping or skimming DVD chapters, we may not register the plot or narration as the makers intended. Doesn’t this make hash of goal-directed action, character arcs, and all the other features of classical storytelling? Might we not be moving toward a “post-classical” cinema?

Movie as book

Let’s tackle the question first from the standpoint of the viewer. I think we can get help by recognizing this basic point: The DVD made a movie more like a book.

This sounds odd, because we think of digital media as replacing print. Yet consider the similarities. You can read a book any way you please, skimming or skipping, forward or backward. You can read the chapters, or even the sentences, in any order you choose. You can dwell on a particular page, paragraph, or phrase for as long as you like. You can go back and reread passages you’ve read before, and you can jump ahead to the ending. You can put the book down at a particular point and return to it an hour or a year later; the bookmark is the ultimate pause command.

We tacitly acknowledge the resemblance between the DVD and the book when we call the segments on a DVD its chapters, the list of chapters an index, and the process of composing the DVD its authoring.

With these similarities in mind, we can ask: How many people, on first contact, would sit down to watch a film in a nonlinear way?

My hunch: Just about as many who would buy or borrow a book and then proceed to read it in a nonlinear way. Now we can grant that if you have a nonfiction book in hand, you might pick out certain chapters as more interesting than others and move straight to those. Similarly, with a DVD documentary on penguins, some viewers might want to move straight to the chapter labeled Mating Habits.

With a fictional film, though, we’re much less inclined to graze and browse, just as with a novel. True, we might sample the novel before buying or borrowing it, but I’d bet the portion we’re most likely to sample is the opening chapter. With a fiction film on DVD, some viewers might skip to a chapter opening or two, but I expect that soon they’d settle down to watching the show at the order and pace of a theatrical screening. This is more or less what happens with literary fiction. The person who starts a novel will proceed in linear order in order to follow the story. It’s a revealing phrase: we’re following a path laid down for us, not racing ahead or falling back.

This isn’t to say that all consumers of fiction move at the same pace or read the same way. I’m just indicating that following the mandated order, page by page or shot by shot, is the default that people adhere to in the overwhelming majority of cases.

This suggests that pausing is the most common way we play an interactive role. When reading a book you might call out to your friend and reread a particularly striking description or funny dialogue exchange. When watching a film, you might stop and replay some images to enjoy them again. Another common act is probably quickly “paging back”—rereading or re-viewing a bit that just preceded the pause to remind ourselves of what’s going on at the moment.

Our purpose in starting a book or film at the beginning is to get into the story world and start to think and feel in relation to the information we get about it. But we don’t have to take that as our primary purpose. More extreme acts of “creative” spectatorship are tied to different purposes than learning about the story world. I suppose that teenage boys might well rent 300 when it comes out on DVD and fast-forward looking only for the scenes showing carnage or naked ladies….the same way that my high-school contemporaries rummaged through Terry Southern’s Candy digging out the good parts. (2) But this doesn’t seem to be a radically new way of using any medium, because the purpose—scanning a text for immediate gratification rather than narrative involvement—was common well before DVD.

Of course we students of cinema use the DVD commands in order to study a film, spooling back and forth to analyze it. But that usage isn’t a radical reworking of consumption either. Typically before we start to analyze a movie, we’ve already experienced it in the ordinary beginning-to-end way. Students of literature execute the same sort of back-and-forth moves studying a text that they’ve read before.

Finally, I’d suggest that a highly unorthodox mode of consumption, like setting out to watch a film in reverse at 8x speed, would become quite boring fast. As with so many things in life, just because you can do something doesn’t mean you’d enjoy it.

Speculation 1: The actual uses that people make of DVD interactivity are limited; traditional beginning-to-end consumption is the default.

Speculation 2: Pausing, paging back, and scanning for the good bits suggest that the most frequent DVD interactivity is familiar from other media, particularly books.

Guided interactivity

Let’s now consider things from the side of the creators. Knowing that films are seen on DVD, don’t filmmakers adjust their art and craft to this new medium? Of course they can provide revised versions, or directors’ cuts, along with alternative endings, deleted scenes, and other material that shed light on the film and the production process. But does the DVD format change the very act of conceiving and executing the story presented by the film?

Yes, in certain respects. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argue that the possibility of rewatching a film with little fuss encourages ambitious filmmakers to “load every rift with ore,” to pack in details that might not be noticed on a single viewing. One of my examples is the 8/2 motif in Magnolia. Likewise, the looping plotlines of Donnie Darko and the reverse-order one of Memento are amenable to being picked apart after several viewings. But before home video, you as a viewer could scrutinize such movies by just going back to the theatre and watching the film over and over, very attentively.

Clumsy as it seems, film nerds of my generation did this. I remember my thrill as a junior in college when I discovered, after rerunning a 16mm print of Citizen Kane on my apartment wall, the snowstorm paperweight that Kane clutches on his deathbed sitting on Susan’s vanity table the night he first meets her. Welles had, as it were, planted this clue for attentive viewers to spot. When we were lucky, we might get a film on a flatbed viewer and go through it reel by reel. Granted, the random-access aspect of DVD allows this sort of micro-analysis to be done much more easily, but it’s not different in kind from rolling up your sleeves and threading up a Films Incorporated print one more time.

I’d add that this sort of scrutiny enriches the film in a very traditional way. Films that sustain this sort of attention, from Buster Keaton silent movies to Hiroshima mon amour and The Silence of the Lambs, long predate the arrival of DVD. Throughout Play Time Tati sprinkled details and gags that reward many viewings. When Paul Thomas Anderson and Christopher Nolan bury details in their films, or when The Simpsons flashes a jokey sign past us, they’re practicing a time-honored strategy of teasing the viewer to return to the work to get something more out of it. Having the DVD at your disposal makes it easier to find half-hidden motifs, jokes, ironies, and the like, but all of these are traditional elements of films both classical and non-classical.

There are, though, more radical cases. The experimental novelist Michel Butor pointed out that the fact that the book is an object to be manipulated at will harbored the possibilities of innovative storytelling. He pursued those in works like La Modification (1957) and Degrés (1960) and theorized about them in an essay, “The Book as Object.” (3) Along the same lines, once a film becomes a booklike object, it can be composed to encourage multiple replays not merely to appreciate little touches but just to make bare sense of what’s going on in it.

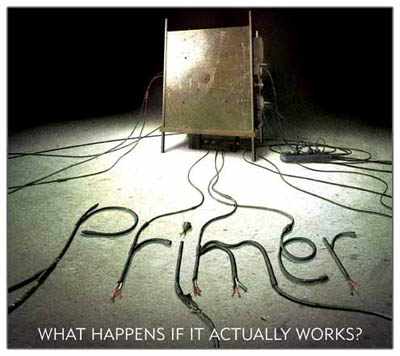

Memento and Primer would seem to be instances. Their makers seem to have designed the films to encourage admirers’ extensive, not to say obsessive, re-viewings. (For analyses of Primer, go here and here.) Again, however, the DVD serves not as a unique format for the film but as a tool that makes analyzing the plots a lot easier than would several visits to the theatre. (4)

There are other possibilities tied to the format itself. The DVD of Max Allan Collins’ Real Time: Siege at Lucas Street Market was designed to permit the viewer some choice of camera angle in certain scenes. At a few points we’re permitted to enlarge the monitors of different surveillance cameras in order to follow one or another strand of action. (Actually, I couldn’t get this feature to work on my players.) Still, in Real Time, the plot action is clear and redundant in the classical manner, so even if you don’t enlarge the screens, maybe you won’t miss much.

Butor suggested that since a book is an object, all in hand at once, a plot could be composed to permit many, equally valid points of entry and exit. Such seems to have been achieved by the DVD version of Greg Marcks’ 11:14. The film is a network narrative, following five characters in a small town as their lives intertwine. The plot is broken into five segments, each one following a character up to the critical moment given in the title. It’s a clever and enjoyable piece of work. In carrying it to DVD, Marcks chaptered it so that you could skip among storylines at will. He explains in an email to me:

It’s a feature on the DVD that I called “character jump,” which allows you to jump to what another character is doing at that same moment in time. Theoretically you could watch the film in an endless circuitous loop because the end is simultaneous with the beginning.

During some scenes of 11:14, a JUMP icon appears and if you press Enter, the scene switches to another character’s storyline—either earlier or later in the theatrical version’s running time. Once in that story, the icon stays on for a bit so that you can return to your point of departure if you want. (4) Presumably for reasons of engineering and disc space, the number of JUMP options remains fairly limited. Still, it’s a fascinating prospect, and it does seem to offer the possibility of your restructuring the plot in fresh ways.

Even in 11:14, however, the story possibilities are closed. As in a Choose Your Own Adventure book, you’re hopping among trajectories that are already designed. The opening remains the opening for every option; no Butor-style starting in the middle. Furthermore, the trajectories themselves are linear, running along a cause-effect pattern very familiar to us from classically constructed stories. (5) We find this often in branching or multiple-draft narratives. I argue in The Way that even the reverse-order disjunctions of Memento sort out along lines to be found in film noir.

Let’s also recall a simple point. Even though the book format offers the sort of mind-bending manipulations Butor celebrates, most literary fiction remains traditionally plotted and narrated. Likewise, we should expect that the arrival of the DVD permits filmmakers who want to tell orthodox stories in orthodox ways keep on doing so. The line of least resistance is straightforward linear presentation.

Speculation 3: The ease of DVD replay can encourage filmmakers to pack their films with more details that repay rewatching. The result might be films that are more “hyperclassical,” to use a term I suggest in The Way Hollywood Tells It –films that are even more tightly woven than we tend to find in the studio years.

Speculation 4: Some filmmakers have made their storylines harder to follow on a single viewing, encouraging DVD replays so we can figure out what’s going on. This strategy makes the films less classical in construction, to a greater or lesser extent.

Speculation 5: A few filmmakers have utilized DVD features to allow greater interactivity than a theatrical screening would grant. In most cases, however, this interactivity rests upon classical guidelines—protagonists with goals, confronting obstacles, conflicting with others, and arriving at a definite conclusion along a linear path.

A stubborn structure

Once upon a time, roughly between the 1920s and the 1960s, movie theatres had a policy of continuous admissions. Metropolitan theatres were sometimes very crowded and patrons had to wait in line outside for seats to be freed up. (Hence the need for ushers to find vacant seats during the screening.) As a result, you might enter in the middle of the movie and watch the film through to the end, sit through shorts and perhaps another feature, and then stay for the opening of the initial film. Hence the expression “This is where we came in.” Doubtless many people planned to see films from beginning to end, but a lot also arrived in medias res.

Someone might speculate that this manner of viewing would encourage filmmakers to indulge in slack plotting. After all, if viewers can come in at any point, a vaudeville-like cascade of acts and incidents—what people are now calling a “cinema of attractions”—would be best. In fact, however, Hollywood feature filmmakers told complex, linear stories of the sort I’ve already mentioned. They didn’t seem to care if viewers were entering midway.

But they really had no choice. If the filmmakers wanted to tell a fairly coherent story, how could they cater to a viewer who might enter at any moment? The only feasible plan, then and now, is just to go ahead and present a story in the linear way, but make sure that it’s presented so clearly that even a viewer entering in the middle can pick up what’s happening. That was, and still is, the default practice. The redundancy of Hollywood storytelling, bent on clear and cogent presentation of the action, is the most effective response to fragmentary viewing.

Hollywood films have been shown in picture palaces, rural playhouses, college classrooms, churches, military bases, and submarines. They’ve appeared on TV, in drive-in theatres, on airline screens, on computer monitors, and now on iPods. In design and execution, the films have stayed remarkably stable. They have relied on our understanding of general principles of storytelling and more specific ones typical of Hollywood. In most cases, this default will stay in place. It works very well, and there’s no alternative that can anticipate all the different ways in which viewers can consume the movie.

Speculation 6: Odd as it sounds, fragmented viewing conditions can encourage coherent storytelling.

Speculation 7: We can’t easily draw conclusions about how films are constructed on the basis of how they’re presented and consumed. Changes in viewing practices don’t automatically entail changes in storytelling.

I’d just add that even in the age of digital media, spectators enjoy greatest freedom not in the way that they manipulate films but in the ways they can interpret them. But even an epic blog has to stop somewhere, so I’ll leave that matter for another time. (6)

(1) You can find the details of our case in Film Art, in Narration in the Fiction Film, in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, in Storytelling in Film and Television, in The Way Hollywood Tells It, and in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema. Also, see Kristin’s “contrarian” blog entry here.

(2) In high school I loaned Candy to a friend and it made its way among my peers with remarkable speed. When I got it back, the pages were falling out. Somehow, our principal Mr. Brown learned that I was the culprit. He gave me a starchy lecture and announced over the homeroom PA system that I was being reprimanded for “bringing a certain book” to school. Mr. Brown was unmoved by my defense that Candy had gotten fairly good reviews.

(3) Translated in his English-language collection Inventory (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968), pp 39-56. The essay doesn’t seem to be available on the Net. So off to the library with you!

(4) Thanks to Colin Burnett, who tested the 11:14 DVD for me while I’ve been away.

(5) Marcks’ DVD version has allowed us to create a Griffith-style crosscutting of plot strands. Interestingly, network narratives are constructed in two main ways: crosscutting the storylines (as in SHORT CUTS) or presenting them in blocks that we must synchronize in our heads (as in PULP FICTION and GO). Marks’ theatrical version gives us the block version of 11:14, while the DVD reveals one possibility of an intercut one.

(6) I’ve discussed film interpretation in a book (Making Meaning) and in chunks of a forthcoming collection (Poetics of Cinema),

PS, 16 May (New Zealand time): Jason Mittell has a fascinating commentary on this topic at his site, Just TV (which isn’t actually just about TV). Jason argues that television narrative has become more complex in recent years and that videotape and DVD technologies have affected that in some unexpected ways. A must-read!