Take it from a boomer: TV will break your heart

Thursday | September 9, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Every so often someone will ask Kristin and me: “Why don’t you write about television?” This is usually followed by something like:

”You’re interested in narrative. The most exciting narrative experiments are going on in TV, not film.”

”You’re interested in visual experimentation. The most exciting developments in visuals are in TV.”

”TV is where the audience is.” Or “TV is where the culture is.”

”Film is borrowing a lot from TV, and producers and directors are crossing over.”

We might answer by saying we don’t watch any TV, but that would be a fib. Like everybody, we watch some TV. For us, it’s cable news commentary, The Simpsons, and Turner Classic Movies.

Truth be told, we have caught up with some programs on DVD. We watched the British and the US versions of The Office and enjoyed both (though the American version, no surprise, makes the characters more lovable). Kristin watched The Sopranos’ first season for a particular project. For similar purposes I watched and enjoyed Moonlighting and some Michael Mann TV material. Intrigued by the formal premise of 24, I dipped into the first season, but I found it visually so wretched I couldn’t continue. I got through four seasons of The Wire on DVD, largely because of the Pelecanos connection, but I found it over-hyped. It seemed to me a sturdy policeman’s-lot procedural, but rather fragmented and uninspiringly shot.

That’s it for the last three decades. No real-time monitoring of episodic TV (we haven’t seen Lost or Mad Men or the latest HBO sensations) and none of the reality shows or the music shows or even comedy like Colbert or Jon Stewart.

So we aren’t plugged in to the TV flow. Americans currently log over four and a half hours a day in front of the tube, so clearly we’re derelict in our duty. As Clay Shirky points out in Cognitive Surplus, TV viewing is Americans’ unpaid second job.

But why don’t I start following episodic TV? The answer is simple. I’ve been there. I was a TV kid before I was a film wonk. And I can assure you that watching TV leads to painful places—frustration, anger, sorrow. All you’re left with is nostalgia.

Commitment problems

I see the difference between films and TV shows this way. A movie demands little of you, a TV series demands a lot. Film asks only for casual interest, TV demands commitment. To follow a show week after week, even on a DVR, is to invest a large part of your life. Going to a movie demands three or four hours (travel time included).

Whether a movie is good or bad, at least it’s over pretty soon. If a TV show hooks you, prepare for many long-term ups and downs—weak episodes, strong ones, mediocre ones. Favorite actors leave or die, and replacements are seldom as good as the originals. A new character may be charming or annoying. An intriguing hero may accumulate distracting sidekicks. Plots take weird turns, sometimes dillydallying for months. All this can drag on for years.

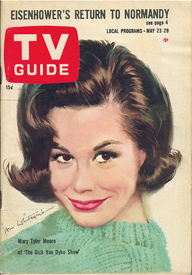

Of course TV-philes enjoy this slow samba. They point out, rightly, that living through the years along with the characters, watching them change in something like real time, brings them closer to us. Who doesn’t appreciate the way Mary Tyler Moore evolved into something like a feminist before America’s eyes? As early as 1952, the sagacious media critic Gilbert Seldes pointed out that intellectuals who thought that TV was plot-dependent were wrong.

It is natural that the actual plot of a single self-contained episode should be comparatively unimportant. . . . The very limitations of the style leads its creators to develop characters of considerable depth, to create dramatic conflict out of the interaction of people rather than out of an artificial juxtaposition of events. As television is a prime medium for transmitting character, this is all to the good (Writing for Television, pp. 115-116)

We get to know TV characters with an informal intimacy that is quite different from the way we relate to the somewhat outsize personalities that fill the movie screen. We learn TV characters’ pasts, their hobbies, their relations with kin, and all the other things that movies strip away unless they’re related to the plot’s through-line.

Having been lured by intriguing people more or less like us, you keep watching. Once you’re committed, however, there is trouble on the horizon. There are two possible outcomes. The series keeps up its quality and maintains your loyalty and offers you years of enjoyment. Then it is canceled. This is outrageous. You have lost some friends. Alternatively, the series declines in quality, and this makes you unhappy. You may drift away. Either way, your devotion has been spit upon.

It’s true that there is a third possibility. You might die before the series ends. How comforting is that?

With film you’re in and you’re out and you go on with your life. TV is like a long relationship that ends abruptly or wistfully. One way or another, TV will break your heart.

TV brat

Trust me, I’ve been there. Unlike most film nerds, I wasn’t a heavy moviegoer as a child. Living on a farm, I could get to movies only rarely. But my parents bought a TV quite early. So I grew up, if that’s the right phrase, on the box.

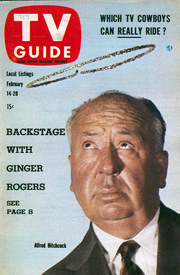

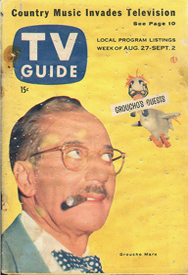

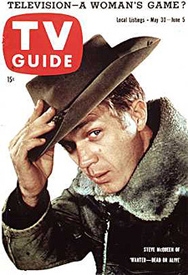

Childhood was spent with Howdy Doody (1947-1960) and Captain Video (1949-1955) and Your Hit Parade (1950-1959) and Jack Benny (1950-1965) and Burns and Allen (1950-1958) and Groucho (You Bet Your Life, 1950-1961) and Dragnet (1951-1959) and Disneyland (1954-2008) and The Mickey Mouse Club (1955-1959). With adolescence came Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1965) and Maverick (1957-1962) and Ernie Kovacs (in syndication) and Naked City (1958-1963) and Hennesey (1959-1962) and The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) and Route 66 (1960-1964) and The Defenders (1961-1965) and East Side, West Side (1963-1964).

Some of the last few titles I’ve mentioned evoke particularly fond feelings in me. At a crucial phase of my life, they presented models of what the adult world might be.

For one thing, adults had an easy eloquence. Some of these shows seem overwritten by today’s standards, but actually they brought to television a sensitivity to language that seems rare in popular media now. Bret Maverick had a smooth line of patter, and even racketeers on Naked City could find the words. Dragnet‘s dialogue is remembered as absurdly laconic, but actually it showed that very short speeches could carry a thrill. At the other extreme were the soliloquys in Route 66. One that sticks in my mind came from a daughter, torn between love and exasperation, saying how touched she was when her father called one of her simpleton boyfriends “uncomplicated.” (The line was modeled on something said by Faulkner, I think.) I don’t recall characters insulting one another as much as they do nowadays, and of course obscenity and body humor were yet to come. At that point, TV relied so much on language that it might be considered illustrated radio.

Second, these shows made heroes of adults who were reflective and idealistic. They mused on social problems and thought their positions through. The father-son lawyers of The Defenders often disagreed about the moral choices their clients had made, and as a result you saw the different ways in which legal cases shaped people’s lives and public policy. Even a cop show like Naked City was less about fights and chases than it was about the causes, and costs, of crime.

Third, adults were empathic. This was partly, I suppose, because I was drawn to liberal TV; but I think it’s striking that my favorite dramatic shows showed professionals committed not to billable hours but to helping other people.

El segundo pueblo

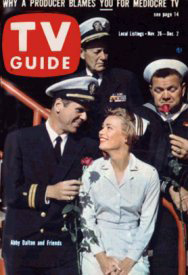

These qualities were epitomized in Hennesey. The continuing cast was small. Chick Hennesey (Jackie Cooper) is a navy doctor in his mid-thirties. His irascible superior Captain Shafer, is played by Roscoe Karns, bringer of dirty fun in 1930s and 1940s movies (“Shapely’s my name, shapely’s my game”). Nurse Martha Hale (Abby Dalton) serves as a romantic interest for Hennesey, and Max Bronski (Henry Kulky) is a dispensary assistant; both are vivid characters in their own right. A few others pop in occasionally, notably the rich eccentric dentist Harvey Spencer Blair III (played with eerie passivity by James Komack).

The series began as a situation comedy, but soon it became an early instance of the “dramedy”—the TV equivalent of sentimental comedy. In this classic genre, moderately grave problems cannot shake the essential concord of human relations. The tonal mixture makes a laugh track distracting; Hennesey‘s was eventually phased out.

The series was created and largely written by Don McGuire, who modeled his protagonist on a doctor he admired. Hennesey is l’homme moyen sensual, a man of no great ambitions or grand passions. He smokes cigarettes (Kent was a sponsor) but, surprisingly, doesn’t drink alcohol. He served in the army when very young (at Guadalcanal), went to UCLA medical school, and was drafted into the navy. Neither a career officer nor an ordinary doctor, he is more at home with enlisted men than the brass.

Hennesey isn’t a dramatic blank, but his virtues are quiet ones. He simply wants to help people get over the daily bumps in the road. He stammers when bullied by someone more aggressive, but sooner or later he quietly stands his ground. When he has a chance to do something decisive, he does it without fanfare. In the pilot episode, he has to override Shafer in order to extricate a man’s arm from a flywheel. But afterward he is likely to wonder whether he did the right thing. He often confesses his fears and weaknesses. Hennesey is a prototype, far in advance, of the caring, sharing male. He is, as Martha sometimes tells him, nice; but that sounds too soft. He is simply decent.

The plot often calls on him to confront people far more harsh and self-centered than he is. Often Captain Shafer, playing the narrative role of Arbitrary Lawgiver, assigns Henessey to unpleasant duties, like dealing with a lady psychologist who wants to find out why men join the navy. Often Henessey has to help men and women adjust to navy life, or to tell them that they are too unhealthy to continue. Sometimes he reminds arrogant doctors why they took up the calling. He also encounters civilians with problems that impinge on his own life. Going home to meet the doctor who inspired his career choice, he finds a bitter widower. In other episodes he simply observes someone else rising to the occasion. A bumbling helicopter pilot is a figure of fun until, behind the scenes, he risks his life to save a girl with appendicitis.

Everything about the series is modest: the level of the performances (only Shafer raises his voice), the accidents and digressions that deflect the plot, the cheap sets and recycled exterior shots, the jaunty hornpipe score that becomes an earworm on first hearing. But all these things enhance that TV-specific sense of a comfortable world with its familiar routines and unspoken bonds of teasing affection.

The show illustrates one of the virtues of TV of the time: talk. Characters emit single lines or even single words at a pace recalling that of the 1930s screwball comedies. Nurse Hale is the fastest, Shafer comes next, and Hennesey is left to play catch-up. In one episode, Shafer has just learned he’s going to be a grandfather, and he leaves the office euphoric. But Martha is a beat ahead.

Hennesey: I betcha this has him in a good mood for weeks.

Martha: For what?

Hennesey: For days.

Martha: Do you want to bet that within thirty seconds he’ll be in a bad mood?

Hennesey: No, that’s ridiculous.

Martha: Is it?

Hennesey: Of course. What could possibly get him upset in—?

Shafer returns, frowning.

Shafer: I just thought of something.

Martha: His first grandchild will be born overseas.

Shafer: Right.

Martha (to Chick): Think you’re playing with kids, huh?

The exchange, including blocking, takes nineteen seconds. It’s conventional, I suppose, but its brisk conviction modeled for one thirteen-year-old the possibility that adults are alert to each moment and enjoy rapid-fire sparring with their friends.

Harvey Spencer Blair III has more highfalutin rhetoric. In a 1961 episode, he declares his plan to run for mayor of San Diego.

Harvey: My election will see the rise of little people to positions of consequence, the molding of our future cultures, the era of a new world. Join with me, my dear, in crossing the New Frontier.

Martha: Leave the petition with me, Dr. Kennedy.

Harvey: I revel in the comparison.

Here even the double takes are modest. Characters react with a frown or a tilted chin or a widening of the eyes or a slight shake of the head. There can be verbal double-takes as well, mixed in with overlapping lines in the His Girl Friday/ Moonlighting manner. At the start of a 1961 episode, Martha enters the infirmary. Henessey is at the desk and Max is filing folders.

Without looking up, Chick says what he thinks Nurse Hale should say.

Hennesey: Morning, Max. Morning, doctor. Sorry I’m late.

Martha: I am not.

Hennesey (looking up): You’re not? It’s ten minutes after eight–

Martha (overlapping): I mean I’m not sorry. I have a very good excuse.

Hennesey: You had a run in your mascara?

Martha: I had to stop and talk to the senior nurse.

Max: Did you get it?

Martha: Yes.

Hennesey: Get what?

Max: Good, I’m glad.

Martha: Thank you, Max.

Hennesey: Get what?

Max: I bet it’ll be nice up there.

Martha: I hope so—

Hennesey (overlapping): Up where?

Max: If it isn’t too cold.

Hennesey: Oh, no, it can’t be too cold, it’s only cold up there in August—that is, if the winds from the equator don’t –Look, you two, don’t you think it’s only fair that if you discuss something in front of a third party, you might just—

Martha: A run in my mascara?

Nobody I knew talked like this, but why not talk like this? It would make life more lively. Backchat, I’ve learned over the years, can get you in trouble; life isn’t a TV show. But I still think that repartee, especially featuring stichomythia, is one of the pleasures of being a grownup. So too are the catchphrases we weave into our chitchat. The Hennesey tag I enjoyed was “El segundo pueblo,” uttered oracularly at a moment of crisis, and always translated with a different, incorrect meaning. My own life would feature motifs like “A meatloaf as big as the Ritz” (undergrad days), “Kitchen hot enough for you yet?” (grad school), and “If I’m gonna get shot at, I might as well get paid for it” (professorial years).

Being a film wonk, I can’t rewatch episodes without noting that those directed by McGuire have some flair. His staging fits the characters’ unassuming demeanor, providing a deft simplicity we don’t find in modern movies. This is doorknob cinema; scenes start when somebody enters a room. And people in the foreground respond to others coming in behind them.

The faster the gab, the slower the cutting, but extended takes can refresh the image by moving actors around. In one scene, Harvey, still planning to run for mayor, is slated for a court-martial. He enters to get the news. His somewhat zombified gait contrasts with Hennesey’s peppy, arm-swinging stride, usually on exhibit during the opening credits. (I learned things about grown-up walking styles too.)

As the shot goes on, Harvey gets the news he’s headed for the brig. Shafer and Hennesey gloat, but in the foreground, Martha suspects that Harvey’s got an ace up his sleeve.

When Harvey says he can’t attend his hearing, Martha lifts her cup: “Here comes the voodoo.”

Harvey reminds his colleagues that he’s due to be discharged from the service before the hearing date. The ensemble responds by regrouping, with Martha and Shafer trading places in the foreground and Hennesey slinking off.

When everybody has assumed a new position, Harvey volunteers to re-up, causing Shafer to shudder.

As Martha sits and Hennesey comes forward, Harvey produces some tickets for his campaign rally, at which Clifton Webb (yes, go figure) will be speaking. Interestingly, Jackie Cooper stays a bit out of sight, preparing for a later stage of the shot.

Harvey leaves, and Shafer’s attention turns to Hennesey as the person to be blamed.

Soon we are seeing characters moving in depth again as Martha gives a typical head-shake in the foreground.

The shot exploits principles of 1940s Hollywood depth staging, as did many of the filmed programs of the period. (The Defenders is particularly rich in this regard.) Simple and sharp, McGuire’s scene is more skilful than anything I saw yesterday in The Expendables.

Chick and Martha got married in the last episode of the series, in May of 1962. I would never see these people again, except in re-runs and syndication. In fact, all my favorite programs were cancelled during my high-school years. I set out for college in summer 1965, disabused of my love for TV. Ahead lay cinema, which would never betray me.

Of course watching a TV series on DVD changes the dynamic of week-in, week-out absorption; but the rhythm of real-time viewing seems to me one of TV’s artistic resources. Besides, wading through a whole series on DVD is still a hell of a commitment.

Gilbert Seldes’ Writing for Television is an original and imaginative study of conventions that still hold sway. He’s especially astute on how the differences in conditions of reception (film, public; TV, domestic) shape creative choices. Another entry on this site discusses Seldes as a critic of modern media.

On the idea that we are especially susceptible to popular culture in our early teens, see our earlier entry here.

Extensive collections of some of my favorite shows, like Reginald Rose’s The Defenders and David Susskind’s East Side, West Side are available for study in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Nat Hiken, a Milwaukee boy, also generously left us a cache of Bilkos and Car 54s.

Hennesey, once rerun on cable channels, has evidently never been published on DVD. Gray-market discs offer a few fugitive episodes, recycled from VHS, kept alive by others with an affection for the program. The most complete information I’ve found on the series is in David C. Tucker’s Lost Laughs of ’50s and ’60s Television: Thirty Sitcoms that Faded Off the Screen (McFarland, 2010), pp. 47-53. A list of episodes and broadcast dates is here.

For more on one staging technique that McGuire uses, you can visit our post on The Cross. See also Jim Emerson’s outstanding analysis of composition and cutting in Mad Men at scanners; the sequence he studies is reminiscent of mine. The best guide to analyzing TV technique is Jeremy Butler’s landmark Television Style.

George C. Scott in East Side, West Side. Stephen Bowie’s Classic TV History site provides a detailed study of this series.

PS 10 September 2010: Believe it or not, I hadn’t read A. O. Scott’s praise of current TV before I wrote this, but his thoughts develop the sort of ideas I mention at the start of this entry.

PPS 10 September 2010, later: Jason Mittell completely understood this entry. If you think that I’m saying TV isn’t worth studying , please read Jason’s careful piece. (In fact, you could count my discussion of Hennesey as an argument for studying TV!)

PPPS 11 September 2010: In my roll-call of TV that Kristin and I watched, how could I have forgotten our devotion to Twin Peaks (1990-1991)? I think I neglected to mention it because we didn’t consider of a piece with ordinary TV. We wanted to follow David Lynch’s career, and we considered the show an extension of his movies. Besides, the series showed the symptoms I diagnosed I mentioned above: episodes fluctuated in quality, and although I liked the later part of the second season better than many people did, its finale was a letdown for me too. For Kristin’s thoughts on Twin Peaks as TV’s equivalent to “art cinema,” see her Storytelling in Film and Television.

PPPPS 5 May 2011: Jackie Cooper died yesterday. The Times obituary glancingly mentions Hennesey, but ignores its real achievements.