Archive for the 'Books' Category

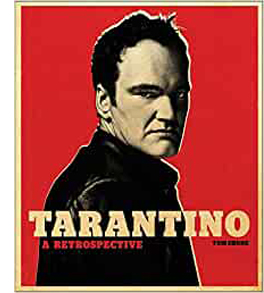

Once upon a time in Hollywood, again: Tarantino revises his fairy tale

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (2019).

I guess what I’m always trying to do is use the structures that I see in novels and apply them to cinema.

–Quentin Tarantino

DB here:

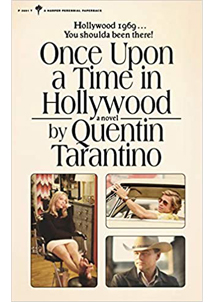

Tarantino has often embraced print-based texts that revise or complement his films. He’s shared screenplays that differ sharply from the finished product, and written graphic novels derived from Django Unchained. Now he’s gone farther. He’s published a novelization that playfully modifies the film’s title: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, without the three-dot ellipsis.

Tarantino has often embraced print-based texts that revise or complement his films. He’s shared screenplays that differ sharply from the finished product, and written graphic novels derived from Django Unchained. Now he’s gone farther. He’s published a novelization that playfully modifies the film’s title: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, without the three-dot ellipsis.

Some will say, rightly, that the book is another instance of today’s tendency toward cross-platform narrative, what Henry Jenkins calls transmedia storytelling. As such it sells more stuff, builds fan connoisseurship, and provides academics like me more to talk about.

But I think it does more. Tarantino has long borrowed from popular literature, particularly crime fiction. (The book I just finished writing tries to trace out some of his debts.) With his novelization, he returns the favor by transferring some of his creative methods to the long-form prose format. Moreover, he realized that some conventions of two genres–the movie novelization and the Hollywood novel–could be steered in fresh directions. What he provides, I think, is not only a fresh path through the story world that will tease fans but also another of his accessible experiments with narrative form. As a bonus, the book shows the author to be a stimulating historian of American studio cinema.

Of course what follows contains spoilers for both the film and the book. But since you’ve had a good stretch of time to catch the film, and since the book currently sits at the top of the New York Times bestseller list, I’m hoping a fairly close analysis won’t scare away many readers. Even if you don’t read on, maybe the mere existence of this entry will send you to the two items in this intriguing multimedia package.

TV or not TV: What is the question?

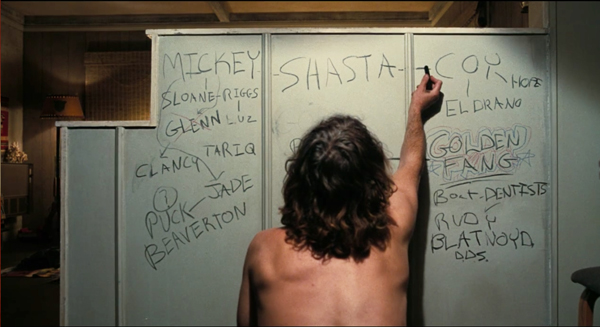

The film weaves together the doings of actor Rick Dalton, stuntman Cliff Booth, and actor Sharon Tate, over the space of a few days. Rick has been hired to play a villain in a pilot for the TV series Lancer, and Cliff, no longer employable as a stuntman, fills his days serving as Rick’s personal assistant, maintenance man, and boon companion. Sharon, wife of Roman Polanski, lives a life of partygoing, shopping, and occasional screen performing. These characters cross paths with members of Charles Manson’s cultist “Family,” who in 1969 actually murdered Sharon and her guests in a home invasion. In the film, things turn out differently. The novelization takes up these characters and basic incidents but recasts them.

The typical novelization is published to promote a film just before its film’s release, and it sometimes serves as an enduring fan memento or a contribution to a franchise’s “canon.” The writer is often working from a screenplay or a detailed synopsis, so changes made in the later phases of production can render the finished film quite different from the book. But Tarantino’s novelization comes two years after audiences saw his film. Many readers have already seen the film, possibly several times, so they will be sensitive to deviations from the original. Tarantino exploits that knowingness in ways that are sometimes traditional, sometimes striking.

As you’d expect, a lot of the book is devoted to filling in the backstory of the three major characters. Flashbacks show how Sharon got to Hollywood and how Cliff became a stuntman (and a killer). Like other novelizations, Tarantino’s fleshes out subsidiary characters as well, providing the sort of enrichment of the story world that fans enjoy. And some scenes omitted from the finished film are dwelt on in the novel. For example, in the original pilot the Lancer half-brothers meet when they accidentally come to town on the same stagecoach. (Sorry about the punk YouTube rip.) Tarantino, always obliging, shot the scene in his own way and provides it as a bonus material on the disc.

The woman in the TV show is the patriarch’s ward, but in the novel and the film she becomes his daughter Mirabella, and thus the men’s half-sister.

Because a novel can plunge us more deeply into characters’ minds, Tarantino can share the thoughts of Cliff, Rick, and Sharon, as well as secondary figures like Squeaky Frome, Pussycat, Jay Sebring, Roman Polanski, and Manson himself. This widening of perspective alters Tarantino’s habitual storytelling method.

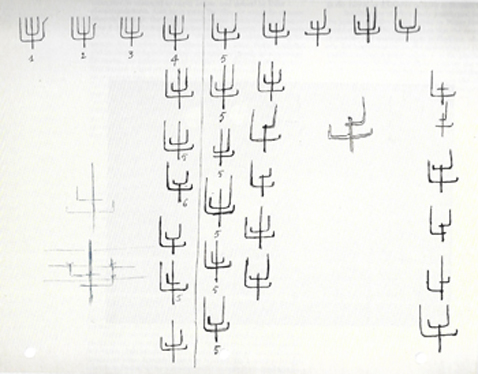

I’ve argued that his films rely on block construction, longish “chapters”attached to one character or set of characters. Whether offering us present-time scenes or flashbacks, they remain fairly self-contained chunks, often set off by titles. As a film, Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood broke with this scheme somewhat and presented more alternation among shorter scenes, though still anchored to one of the three main characters.

The novel is even more chopped up, presenting the story in twenty-five chapters, many of them including shifts in time or viewpoint. The transitions are clearly marked, with inner monologues rendered in italics and verb tense differentiating the present-time story from flashbacks. In all, the short, sharp scenes sample a broader panorama of Hollywood life than we find in the film, yielding something more like a network narrative.

The same expansion goes for time. The film leaves Rick’s future somewhat open, but the book sketches in his career after his confrontation with the Family marauders. We learn fairly early in the book that in the 1970s he will cut down on his drinking, an important motif in the book. We also learn the career arc of Trudi Fraser, the little girl with whom Rick performs in the Lancer pilot. A more conventional novelization probably wouldn’t include this anticipatory material, because it would foreclose developments that filmmakers might want to conjure up in a sequel.

Still, Tarantino does adhere to his block aesthetic in an odd way. Big chunks of the Lancer backstory not dramatized in the TV episode are given to us in dedicated chapters, written as if they were extracts from another novel. Recounted by an omniscient narration, they treat the Lancer family history on the same fictional level as the contemporary Hollywood plot. Why? I’ll try to explain below.

Tarantino has experimented with viewpoint shifts and replays throughout his work, most notably in the repeated money-drop sequence in Jackie Brown. Now, like a writer of fan fiction, he can extend the strategy to prose. So an episode registered by one character in the film can be filtered through another in the book. The most extended viewpoint displacement involves Cliff’s visit to Spahn ranch. In the film, we’re attached to him throughout, but in the book everything that happens in that scene is restricted to what Squeaky sees and hears. Viewers are likely to remember Cliff’s fruitless conversation with George, so the replay allows Tarantino to build up a more sympathetic portrait of Squeaky than we get in the film.

Two other narrative strategies are more surprising, but both target readers’ memory of the film. First, the book begins with an office conversation between Rick and agent Marvin Schwarz that echoes the restaurant meeting that opens the film. The reader is likely to think that the book’s ending will resemble the film’s end, which shows the Manson followers attacking Rick’s house rather than Polanski’s. This is the most drastic “alternative history” in the film, like the assassination of Hitler in Inglourious Basterds.

But the reader who’s seen the film will be thrown off on page 110. In a flashforward to March 1970, Rick gets a call from director Paul Wendkos inviting him to join a project. Prompted by a teasing remark by Wendkos, the narration quickly summarizes the summer 1969 invasion and its aftermath before briskly scanning the effect on Rick’s career in the seventies. If you’ve seen the movie, now you can’t be sure what will happen at the end of the book. Will the book’s climax replay the movie’s firefight? Or will something else tie up the plot? Call it show-offish or shrewd, Tarantino’s anticipation of the film’s ending has activated the reader’s awareness of his choices about narrative structure.

Related to this replacement-ending problem is a shift in rendering the filmmaking process. The film shows two scenes of the Lancer pilot being filmed. In the first, Johnny Madrid/Lancer rides into town, shoots down a hired gunman, and discusses joining Caleb DeCoteau’s gang. In the second scene, Caleb holds Lancer’s daughter Mirabella hostage while he arranges for ransom from Scott Lancer.

But the novel version only alludes to these scenes; it doesn’t dramatize the filming of them. The meeting of Johnny and Caleb is presented as part of the inserted Lancer “novel,” while the hostage parley is merely mentioned. The only scene that the book describes being shot is one for Rosemary’s Baby.

Instead, the novel dwells on what happens before shooting. On a porch Rick and Trudi discuss acting in general, and later she urges him to scare her during the hostage scene. Tarantino suppresses the act of filming this big scene, simply indicating laconically: “And Caleb and Miranda act out the scene.” Likewise, Sharon Tate, recalling her slapstick scene in The Wrecking Crew, dwells on what happened before the camera rolled.

Why the shift from filming to preparation? I’ll suggest one possibility a bit later.

Palimpsest of a period

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a “Hollywood novel.” Typically that genre centers on the rise and fall of a fictional star (Inside Daisy Clover) or an executive (The Last Tycoon), with glimpses of production woven in. The fictional characters dominate the plot, but there are references to actual people and studios, which (libel laws being what they are) serve mostly as colorful background. Tarantino follows these guidelines, but he offers a deeper analysis of American film history than any other Hollywood novel I know.

His isn’t a dry historical approach, though, because of the flamboyance displayed by the narrator. Instead of giving us a prudent bystander’s account in first-person narration, as What Makes Sammy Run? does, the book presents an omniscient yarn-spinner addressing us through phrases like “And bear in mind,” “Now, truth be told,” and “You must remember.” At the same time, efforts at purely literary bravado mix the cheap tabloid alliteration of James Ellroy with the weirdness of Cornell Woolrich.

Still, none could really match Aldo Ray when it came to publicly played-out poignant pity.

The six powerful equines come to a gentle stop.

The diminutive Polanski sports bed head on his cranium.

Who’s speaking? This narrator is at once omniscient and lightly personified. The Lancer segments are straight Western-novel narration, except when they’re not.

With his light Texas twang, Monty sang out, “Royo del Oro, last stop!” The backlit sunshine rays filtered through the gauze-like brown dust in the way, a hundred years from now, all cinematographers of western movies would hope to duplicate.

An “I” almost never creeps in, but throughout we’re hearing the Tarantino who produces interview patter and whose screenplays insert wise-ass stage directions.

Freddy finishes his playing-possum piss (Reservoir Dogs).

Everyone is smiling except you-know-who (Pulp Fiction).

From the floor, the bloody, sweaty, and in excruciating pain (she’ll probably lose that leg) German movie star says to the two American soldiers she’s just meeting for the first time. . . . (Inglourious Basterds).

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood goes some way to confirming Tarantino’s repeated claims that when he stops making movies, he’ll turn to novels. I will read them.

Every Hollywood novel is in a sense an alternative history, I suppose, but this unpredictable prose helps prepare us for something peculiar. Start with the time frame. The first and longest stretch of the film takes place on Friday 7 January 1969 and the following day, and these chapters are tagged with time indications. The film then skips ahead to the day and night of 10 August 1969, with the attack on Rick’s home. The book adheres to the February dates but as we’ve seen it “spoils” the film’s climax by announcing the massacre fairly early on.

The central action of the book confines itself to the two days when Rick meets Schwarz and shoots the Lancer pilot, on 7-8 February, 1969. But that chronology is thrown off by another tag. After chapters presenting the day and evening of Friday the 7th, a new chapter indicates that Pusssycat’s Kreepy Krawl (another Ellroyism) takes place at 2:20 AM on that day. It’s either a flashback to an early-morning period before the previous four chapters (why?) or a scene taking place after the earlier chapters, and so is occurring at 2:20 on the 8th, not the 7th.

The Krawl anomaly is an early indication that a misaligned calendar governs the whole book, as it did the film. The actual Lancer pilot was shot in 1968, not 1969. Tarantino has merged events of one year (Rick’s career crisis, the Lancer shoot) with those of a later one (the actual Tate-LaBianca murders).

The typical Hollywood novel inserts made-up stories into a world of real ones, but Tarantino goes further. Your typical director would have pasted Rick on the cover of Time, but Tarantino goes for Mad. Your average movie-geek director would have had Rick reading an actual western novel, maybe Hombre in homage to Elmore Leonard. Instead, Tarantino invents a novel, Ride a Wild Bronc, by the real author Marvin H. Albert, because he wants a parallel between Rick and that book’s hero Easy Breezy. (The fact that Albert himself wrote many novelizations is a bonus.) Likewise, amid a flood of information about genuine Paul Wendkos films and stars therein, Tarantino deletes one actor (James Franciscus) from Hell Boats (1970) to cast the fictitious Rick in the part.

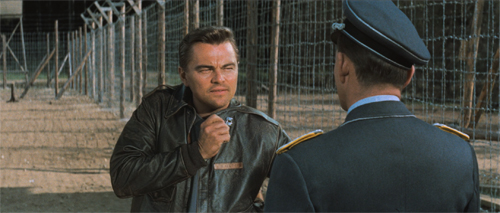

The substitution gambit is literalized in the film, when we learn the gossip that Rick supposedly just missed getting the McQueen part in The Great Escape (1963).

A comparable substitution conceit in the book is the jumble of publisher advertisements printed in the back. What could Tarantino’s book promote? Other books of the period published by Harper, of course: Oliver’s Story (1978), Serpico (1973), and Leonard’s The Switch (1978). The dates suggest that the “original” version of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was published in the late 70s, and this accords with hints in the narration and the book’s design. These period ads sit alongside one for the fake Ride a Wild Bronc and one for a purported hardcover edition of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (fake? forthcoming?).

Yet these dabs of phony history allow the book to float some genuine historical analysis. The constant references to obscure movies and TV shows might be taken as merely Tarantino’s nerdy self-indulgence. In fact, these citations fit into a fairly coherent cross-section of the period’s filmmaking and film culture, with the trends filtered through the business decisions and personal tastes of his characters. 1960s Hollywood turns out to be a palimpsest.

One layer is the fading of the studio system, reflected in agent Schwarz’s boast that he handles old royalty like Farley Granger and Joseph Cotten. Rick expresses his admiration for classic B-picture directors Wendkos and William Witney. Sharon’s backstory, when she hitched a ride to LA, reminds us of the enduring Hollywood myth of fresh-faced outsiders breaking in.

There’s also the new competition from European genres and overseas art films. Cliff, who scorns Antonioni and Resnais, is a big fan of Kurosawa and I Am Curious–Yellow. Now a European arthouse director has made a smash American hit, Rosemary’s Baby, and Rick fantasizes being tapped by Polanski. By contrast, Rick is reluctant to venture into spaghetti westerns, the new territory for a has-been US star.

“TV,” people used to say, “gets ’em on the way up or on the way down.” That’s been pretty much Rick’s career trajectory. Broadcast television has disrupted everything. B-directors like Wendkos shift between the two media, but the A-list older stars can’t sustain a series. Still, the narrator admits that some of these “sought to subvert their personas,” as Henry Fonda did in Once Upon a Time in the West.

Young talent is on the make. James Garner, James Coburn, and many other TV stars can jump to film, while Lee Marvin can shift from B-film villainy to TV heroism (M Squad) and return to films to play dark lead roles. The most shining example is Steve McQueen, who after his series Wanted–Dead or Alive became a top film star. In Tarantino’s film, he’s briefly seen commenting on Polanski’s ménage, but in the book McQueen haunts Rick’s life. The misbegotten anecdote about The Great Escape follows him everywhere.

At forty-two Rick is caught between two trends. He’s loyal to older directors and a classic genre, and he hates Eurowesterns and the counterculture. But to keep working he’s in competition with “the three Georges”–Peppard, Maharis, and Chakiris. Ten years ago he had his own series. Now he must wear a mustache and a biker wig and be the bad guy shot down by the newest “swinging dick.”

Said dick would be, in the Lancer pilot, James Stacy, to whom an entire chapter is devoted. He is the next failed McQueen, the young paladin who started memorably on Gunsmoke but now realizes that the clean-cut bad boy is on the way out. He admires Rick’s early work and envies Rick’s “fucking fly” look as Caleb. He yearns to wear a mustache.

The TV western has developed its own conventions, which Tarantino’s novel filters through the characters’ awareness. Schwarz introduces us to the antagonism between the series hero and the heavy, emphasizing that with every one-shot appearance, the guest star’s image suffers. After Rick reads the Lancer script, he admires its boldness in choosing as a protagonist Johnny, the sort of cocksure hothead who’d normally be shot down in the last act. Trudi is well aware that she is “just the ‘little tyke’ series regular.” More broadly, the book’s narrating voice realizes that westerns are based on “the man of principle pushed past his breaking point and beyond his nature. Most of Greek tragedy, half of all English theater, and three-quarters of American cinema operated from this premise.”

Men in war and at work

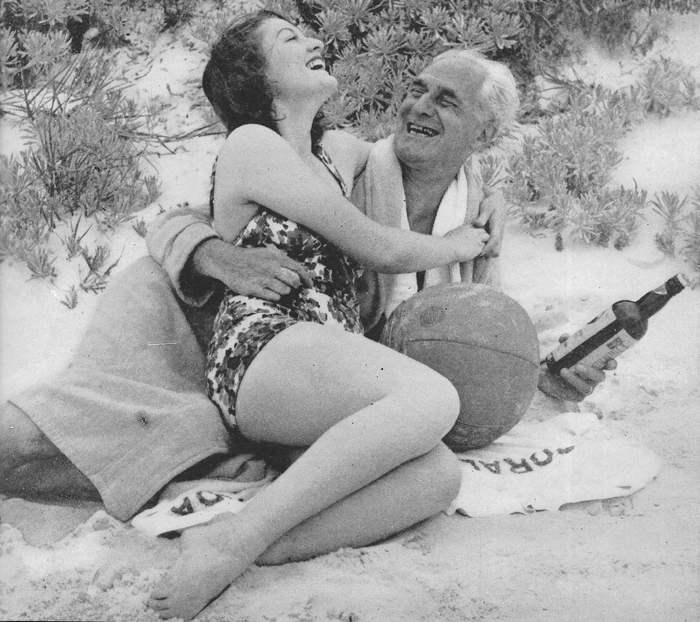

Men in War (1957); Aldo Ray on left.

The book spares some thoughts for women working in Hollywood. Schwarz’s secretary Miss Himmelsteen winds up becoming a talent agent who also performs fellatio on her clients. Sharon Tate, who prefers the Monkees to the Beatles, is fully aware that she’s playing the role of “sexy little me” in most social encounters. Yet she genuinely enjoys the audience laughter aroused by her klutzy scene in the not-very-good The Wrecking Crew.

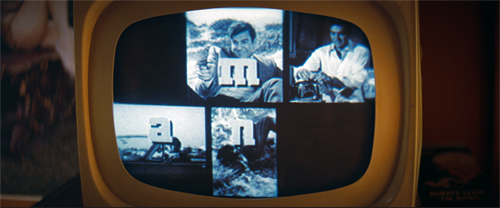

Still, the book dwells far more on the men. The Mannix episode on Cliff’s TV spells it out.

These men are anxious. Both Rick Dalton and James Stacy see their futures endangered. Charlie Manson is trying to build a career in the music business, but his clumsy networking reveals him as a loser. Most strikingly, in devoting seven chapters to Cliff Booth’s life story, the narration presents a composite of trends swirling through the period.

We who’ve seen the film know Cliff’s manic, LSD-buzzed defense of Rick’s home. But who is he? This war hero who has murdered his wife and three other people is a hard case with a soft spot for foreign films. He’s a dog lover who put his pit bull Brandy through harrowing fights. He hurls Bruce Lee against a car but, out of concern for George Spahn, worries that the hippies encamped on his ranch are exploiting him. If Rick and James’ niches in the hierarchy are shifting, Cliff knows his place is near the bottom. Living in a crummy trailer eating Kraft Macaroni & Cheese, he can survive thanks to his muscle and his wits. He might be a man of principle who’s just pushed past his breaking point a bit too often.

Enter Aldo Ray, an actual actor whom Tarantino has long celebrated. Despite working with George Cukor, Anthony Mann, Raoul Walsh, and other top directors, Ray destroyed himself through alcohol and wasteful spending. He gets his own chapter near the end, brought into the story when Cliff is stunting on a runaway production in Spain. While Charles Bronson is becoming a star, Aldo is sinking into a numb despair. He is what Rick or Stacy might become.

As the book closes, this parade of masculine misery replaces the film’s Manson Family siege. After finishing the day’s Lancer shoot, Rick and Stacy head out to the Drinker’s Hall of Fame, a tribute to great Hollywood drunks. Cliff and other acquaintances join them, and they share stories of their sex lives and the productions they worked on. Rick finally manages to spell out why he hates the Great Escape rumor. He admits to his peers that he never really had any chance for the McQueen part. That clarity seems to give Rick a dose of prudence: he leaves early because he needs to learn his lines for tomorrow. For the reader, the drinking bout chimes with Aldo Ray’s plight in the prior chapter, and it suggests how Rick will survive the 1970s. His reconciliation with Stacy will lead both to keep their alcoholism under better control.

Rick’s flash of self-discipline is among the many epiphanies that pile up in the final pages. Sharon, sweet-natured throughout, now gets annoyed with Polanski’s whining bossiness and maneuvers him into holding a pool party. Schwarz calls Rick and offers him a chance for a spaghetti western. Rick runs into Steve McQueen, and his resentment of the superstar drains away in a shared memory of male camaraderie, a pool game long ago. Above all, Rick gets a call from Trudi that resets his relation to his past and his craft.

An actor prepares

Tarantino admires directors, but he adores actors. Has any film more fully portrayed the insecurities of performers? Rick sees his career going down the drain while upstarts like Stacy and the coolly competent Trudi Fraser, only eight years old, are more professional than he is. Rick is baffled by the director’s pretentious ambitions (“Be evil sexy Hamlet”) and rages in his trailer when he blows his lines. Each small error confirms Schwarz’s diagnosis that Rick can flourish only in a downmarket cinema, below even episodic TV.

One of the film’s finest sequences builds enormous tension when it shows Rick struggling to keep up with Stacy in their saloon reunion.

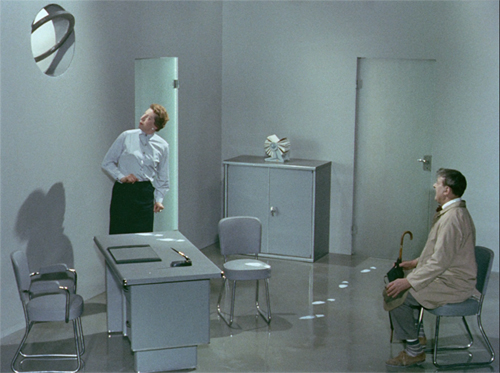

Tarantino could have shot this sequence in 4:3 ratio and TV style, in accord with the Bounty Law commercial that opens the movie. But the bar sequence, like the hostage scene to come later, maintains the same stylistic tenor–widescreen, long takes, rich color–that presents the story of Rick, Cliff, and Sharon. Remarkably, we don’t see any shots of the director and crew watching the performance. The production staff remain offscreen, cueing Rick’s lines. Tarantino has fused the modern camera with the TV camera, “rewriting” the TV production with shadowy modern lighting and arcing camera moves. This filming strategy puts the pilot on par with the surrounding story, just as in the book the Lancer family saga carries the same weight as the 1969 story line.

At the same time, the sequence lets us see just how difficult film acting is. (You can see Stacy trying to match his spoon’s movements to get a clean retake.) An awkward axial cut-in to the bartender delivering Johnny’s beans may be hinting that already Rick has blown a line and they had to reshoot it.

Acting is hard. Even bad acting is hard. Could you or I do what Rick has to do in this scene?

Seeing Rick’s malfunctioning performance in this scene puts more pressure on the big hostage scene, which again runs as if it’s part of the surrounding film. But now, after Rick aces the scene, we get our first crew shot and the director’s happy reaction, along with Trudi’s whispered praise.

Even more than the film, the book pays homage to the strain of actors’ working lives. By sequestering the Lancer episodes in separate chapters, Tarantino can focus elsewhere on the sheer terror of preparation for filming them. Now we see why the book stresses the performers’ leadup to each shoot. We’ve seen in the film how harrowing it is to screw up, and the book digs into the panic of preparation.

Which is why, I suggest, the book ends with one more phone call. (The back cover of the paperback hints at its imporance.) Suspecting that Rick is slacking off, Trudi calls Rick to goad him into rehearsing. As they start to run the lines, they slip into their characters. The narration cooperates.

Which is why, I suggest, the book ends with one more phone call. (The back cover of the paperback hints at its imporance.) Suspecting that Rick is slacking off, Trudi calls Rick to goad him into rehearsing. As they start to run the lines, they slip into their characters. The narration cooperates.

Caleb answers flippantly, “Greed’s what makes the world go ’round, little lady.”

The little lady says her name out loud: “Mirabella.”

“What?” Caleb asks.

The eight-year-old child repeats her name to the outlaw leader. “My name is Mirabella. If you’re gonna murder me in cold blood, I don’t want you to just think of me as Murdock Lancer’s little girl.”

Something about the way she says that registers with the outlaw. And suddenly it becomes important for Caleb to make her understand his fairness on this matter.

Through Rick’s performance the narration can plunge into Caleb’s mind. Things get even more complex when Johnny enters the scene, voiced by Trudi.

Trudi as Johnny points out, “Something happens to that money and we don’t get it, that’s our problem.”

Caleb spins toward Johnny and violently says, “Something happens to that money, that’s her problem!” With fire in his eyes, he tells Johnny Lancer, “Git it straight, boy! . . .”

Very soon Caleb will be shot dead, as enacted by Rick over the phone.

As usual, we won’t see the scene filmed, but Trudi foresees the result. “We’re going to kill this scene tomorrow.” Rick agrees. When she adds that they’re in a great line of work, Rick has his biggest epiphany. Trudi is right. The career that seemed so dismal has let him work with great actors, make love to beautiful women, enjoy luxuries most men never dream of.

He looks around at the fabulous house he owns. Paid for by doing what he used to do for free when he was a little boy: pretending to be a cowboy.

Boys will be boys, apparently forever.

Tracing three movie careers–a fading star, an aspiring starlet, and a below-the-line crew member–the film and the book provide Tarantino’s views not just of swinging-60s Hollywood (“You shoulda been there!”) but what working in The Business is like. Like most books and movies set in the film capital, these two texts show the pleasures and pains of a life that’s at once glamorous and dangerous.

But thanks to visual and verbal bravado, ingenious crosstalk between cinema and prose, and a respect for actors, Tarantino has gone beyond the usual finger-wagging chastisement of Hollywood excess. His taste for low-grade product, which has sometimes seemed an auteur provocation, is revealed as a respect for the desperate energy that animates even barely talented performers. That stubborn struggle, he suggests, is more rewarding than hippies’ hopes to mosey into nirvana.

Tarantino’s respect for those who dare to make movies, even opportunistic and down-market ones, puts him squarely in the classical Hollywood tradition of striving professionalism. His protagonist realizes, Capra style, that he has a wonderful life. Weird as it sounds to say it, Tarantino’s multimedia fairy tale might be the squarest story he ever told.

The epigraph comes from Graham Fuller, “Answers First, Questions Later,” in Quentin Tarantino: Interviews, rev. ed., ed. Gerald Peary (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2013), 37.

More homework for the Tarantino squad: Trudi Fraser in the film is Trudi Frazer in the book.

Jeff Smith’s discussions of the film, here and here, were our most popular 2019 entries. They still hold up.

Through a blunder, I missed seeing Mark Minett’s careful email reply to my question about the saloon dialogue scene. Would such an arcing shot be likely in network TV of the period? His response is very helpful:

As for lateral or arcing camera movements during shot reverse shot sequences, I think these must be pretty rare. It’s possible a show might feature one every once and awhile, but these would likely stand out as a directorial flourish. The late 1960s television I’ve seen tends to have static s/rs, with variety achieved through camera height and angle, though I did just see an episode of Hawaii Five-O where the reverse shot was a moving close-up of a pacing Jack Lord.

Typically, you’d get mobile framing as you set up the key figures and then cut into the s/rs sequence. We sort of get that in the LANCER sequence as they sit to eat, and then there’s that interesting jump cut and track back reset as the man approaches with the food (I wonder if this was supposed to signal imperfection and authenticity or what?). Or, you could get a push in on a face at a climax, usually as they move out of the scene or to a commercial, as in the “1958” Bounty Law footage, though I think the more common option was just to hold on a close-up. That arcing move around the back of Olyphant’s head in Lancer, though, would be unusual, I think.

I wonder if it’s worth distinguishing this kind of arcing movement that basically just resets the framing of the scene, from the kind of arcing movements that seem more common now, which continue across cuts and underwrite the dramatic tension of a sequence. The former seems like more of a possible – though still probably very rare – option on the menu of that era’s filmed television, while I’d be really really surprised to find the latter. These are all just somewhat informed hunches, though, and there’s definitely room for real research here. Arcing and lateral movements aside, I’m also not sure when s/rs sequences in filmed TV started to regularly incorporate the slow push-ins that develop over the course of a sequence. So much worth investigating!

Mark should know. He’s the author of an excellent book on Robert Altman’s work, with close study of his TV projects. Another scholar of televisual style, Jonah Horwitz replied as well.

I don’t really have much to add to Mark’s response except nods of agreement. I don’t have the Tarantino movie to hand but the kinds of embellishments David describes would be pretty rare. S/R/S, as Mark notes, tends to be locked down (though not usually as metronomic as on Dragnet!)

A few folks have made some very tentative arguments for directorial style in midcentury US series TV partly on the basis of camera movement—that is, based on ambitious movements being the exception rather than the rule. Some of the former live TV directors I studied tried to import their love of long takes and elaborate camera movements into telefilm production with very mixed success (often they ran into the opposition of producers who wondered why they weren’t getting through x number of setups per day). Some of Joseph H. Lewis’s ’50s TV episodes stand out—in spots—for such things.

Re. Mark’s question, in live TV drama S/R/S is typically handled using long lenses, which made precise or ambitious camera movements somewhat difficult for such sequences. I argue in my dissertation that much of the innovation in S/R/S in live TV drama came from finding ways to get more frontal angles on characters without the camera shooting the reverse-field intruding into the shot. Earlier live drama S/R/S set ups have an obliquity owing to the shooting situation. (If you imagine the prototypical S/R/S staging with a camera placed in front of each character, you can see the problem.) Later directors and cameramen mitigated this through careful planning and extremely dexterous crews. But, again, this is in 50s/early 60s live TV—far from the late 60s telefilm that Tarantino is supposedly pastiching.

I wonder if the partially anachronistic shooting style of the Lancer segment could be motivated by the dream-film aspect of the movie (or maybe given Tarantino’s tendency to flagrant stylization we don’t even need recourse to a more specific alibi).

P. S. 21 July 2021: Tarantino discusses the book in a fascinating interview with Mike Fleming, Jr. at Deadline.

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

What you see is what you guess

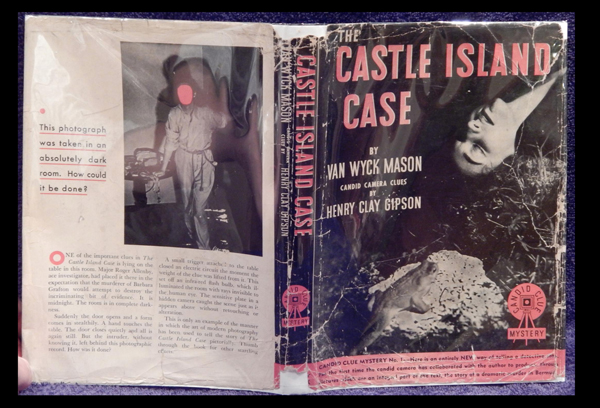

The Castle Island Case (1937).

DB here:

In the 1920s and 1930s, stories of mystery and detection became hugely popular in Anglophone countries. Britain’s “Golden Age” of whodunits, launched by Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers, was rivaled by the emergence of American hardboiled detection, personified by Dashiell Hammett and other writers for the pulp Black Mask. Some of the detectives, such as Philo Vance and (alas) Ellery Queen, are largely forgotten today, but others remain towering figures of popular culture. Surprisingly, new Sherlock Holmes stories were still appearing in the 1920s. In addition, there emerged Hercule Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey, Charlie Chan, Sam Spade, Nick and Nora Charles, Nero Wolfe, Philip Marlowe, and Perry Mason (recently revised in a noir version for streaming). Fiction, film, comic strips, and radio all disseminated their adventures. Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys were aimed at the kids.

Amid this vast 0utput, writers needed to differentiate their work. The search for gimmicks was on, and a few were, as we’d say now, a little interactive. Since the classic detective plots centered on puzzles, publishers added games and playful ancillaries to their books.

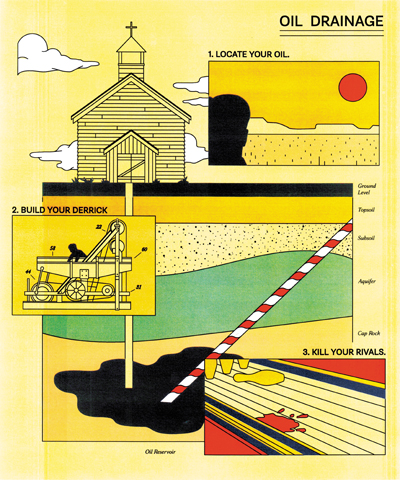

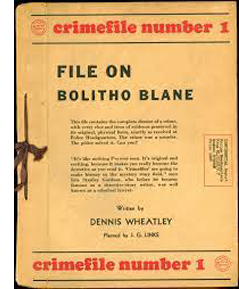

Some novels were published with the last chapters sealed, daring buyers to resist curiosity and return the book for a refund. A novel (The Long Green Gaze, 1925) might tuck clues into crossword puzzles (another 1920s fad) that the reader had to solve. Books came packaged with jigsaw puzzles (The Jig-Saw Puzzle Murder, 1933; Murder of the Only Witness, 1934). “Murder dossiers” like File on Bolitho Blane (aka Murder in Miami, 1936) assembled facsimile documents accompanied by matchsticks, strands of hair, bloodstained scraps of fabric, and other physical clues. The party game of Murder, in which guests were assigned roles of victim, culprit, witnesses, and detectives, became a craze and was, naturally, incorporated into novels (Hide in the Dark, 1929).

Some novels were published with the last chapters sealed, daring buyers to resist curiosity and return the book for a refund. A novel (The Long Green Gaze, 1925) might tuck clues into crossword puzzles (another 1920s fad) that the reader had to solve. Books came packaged with jigsaw puzzles (The Jig-Saw Puzzle Murder, 1933; Murder of the Only Witness, 1934). “Murder dossiers” like File on Bolitho Blane (aka Murder in Miami, 1936) assembled facsimile documents accompanied by matchsticks, strands of hair, bloodstained scraps of fabric, and other physical clues. The party game of Murder, in which guests were assigned roles of victim, culprit, witnesses, and detectives, became a craze and was, naturally, incorporated into novels (Hide in the Dark, 1929).

The most outrageous of these extramural activities was Cain’s Jawbone (1934). The 100-page story purports to be a mystery novel whose whose pages were accidentally printed and bound out of order. There is, the reader is assured, only one correct sequence, although “the narrator’s mind may flit occasionally backwards and forwards in the modern manner.” The publisher offered a prize to the first reader who could submit the correct ordering–and, not incidentally, name both the murderer(s) and the victim(s). Only two people hit on the answer, which still remains unknown to the public.

Even quite well-known writers joined in. The original editions of Sayers’ Five Red Herrings (1931) left a page blank so that the reader could jot down a guess at what Lord Peter asked the police to find at the murder scene. Sayers was quite proud of “this little stunt,” and floated the possibility of printing the missing passage in a sealed page at the end of the book. She also wrote a Lord Peter story that invited the reader to solve a rather recondite crossword. Q. Patrick composed a murder dossier, The File on Claudia Cragge (1938).

Less immersive but still pretty interesting was my topic of today. I think it coaxes us to think about how pictures and text can interact, and how a book can borrow film techniques. In addition, it has enough weird touches to make it a remnant of a period in desperate search of storytelling novelty. You know, like ours.

More highly seasoned than most

With The Castle Island Case (published September 1937) a fairly famous author, Van Wyck Mason, introduced what he considered “a brand-new method of telling a mystery story.” That method involved accompanying the novel with staged photographs of the characters, clues, and crime scenes. Mason insisted that he and photographer Henry Clay Gipson came up with the idea before the first murder dossier (1936) and before Look magazine’s “Photocrime” series, which began running in June of 1937.

Novels had long been illustrated; our undying conception of Holmes owes a good deal to Sidney Paget’s vivid drawings in the original stories. And comic books, which had begun telling long-form stories in the 1930s, showed that pictures (helped out by verbiage) could sustain plots. But photography changes the status of the image. Mason believed that photos could be not “mere illustrations but an essential, integral part” of the novel.

Interestingly, he doesn’t rest his case on realism, the idea that the story would seem more plausible if it contained documentary images. But surely the appearance of a photographic record gives a forensic quality to the shots of clues and corpses. At the period, tabloids and even “family” magazines like Life and Look were incorporating gory crime-scene images.

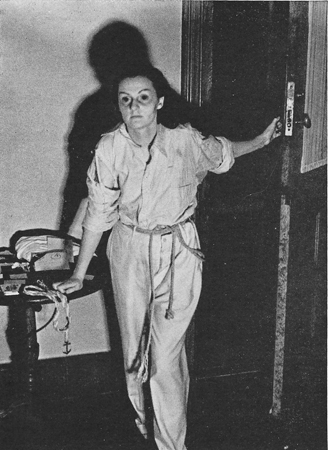

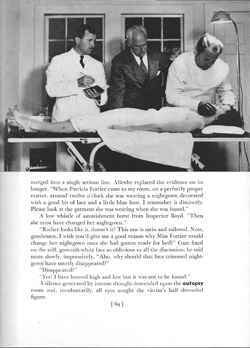

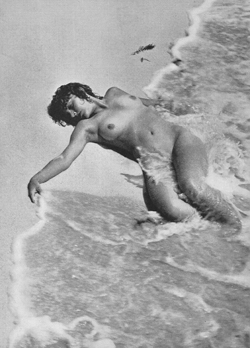

In The Castle Island Case, as befits fiction, these are more artfully composed. The shots of Allenby at an autopsy and of a topless woman washed onto the beach, we’re told, “were a very definite part of the story and were not included merely for effect.”

Still, they are a bit startling in their prim sensationalism. (One reviewer: “A thriller more highly seasoned than most.”) The book’s up-and-coming publisher, Reynald & Hitchcock, had developed a reputation for daring: it published Hitler’s Mein Kampf in a complete translation the same year as Mason’s novel. Later the firm would issue policy books from a liberal standpoint and, in 1944, the controversial Lillian Smith novel Strange Fruit.

For the shoot Reynald & Hitchcock flew the cast to Bermuda, where Mason lived. The story incorporated the exotic scenery and local life, notably a Gombey performance. Mason and Gipson accumulated about 600 stills in ten days, and they checked their results immediately, processing films far into the night. The finished book includes 180 or so shots, printed alongside text on glossy paper and bound in a large 7½ x 10-inch trim size that make them easy to study. An essential hook, trumpeted on the dust jacket, is that you can examine the pictures to find evidence that the text doesn’t mention. This was to be the first in a series of “Candid Clue Mysteries”–crime traces captured by the candid camera.

Picture this

Major Roger Allenby has flown to Bermuda to help an old friend whose daughter Judy has gone missing. She was serving as secretary to millionaire Barnard Grafton. Allenby arrives under the pretext of joining Grafton’s shady business deal with the president of Ecuador. Grafton is hosting other potential investors and several female guests. The set-up is a classic mystery situation: an isolated setting and a small group of wealthy people, some of whom will die or disappear, leaving the others as suspects. Soon Judy’s sister Patricia, who has replaced her on Grafton’s staff, is murdered.

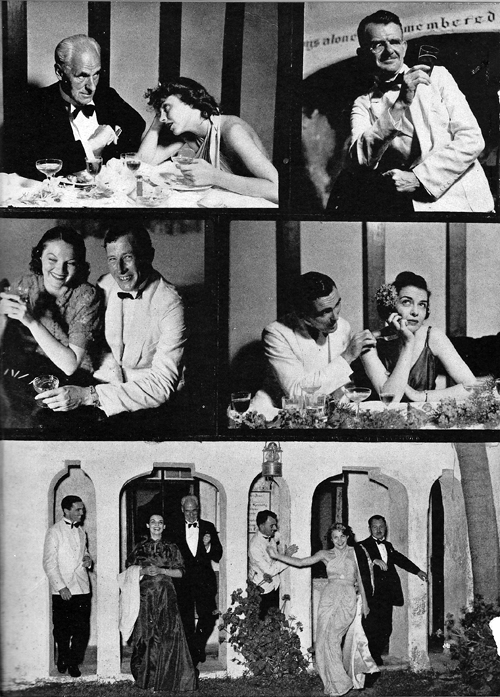

The photos are of three types. One operates as classic illustrations, showing all the characters from an impersonal perspective. So Allenby can be seen among others, as in the rather Straub/Huilletian autopsy image above. A second type of images is more “omniscient” and free-ranging, filling us in on background information.

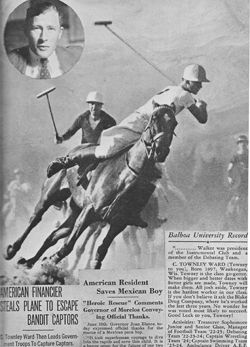

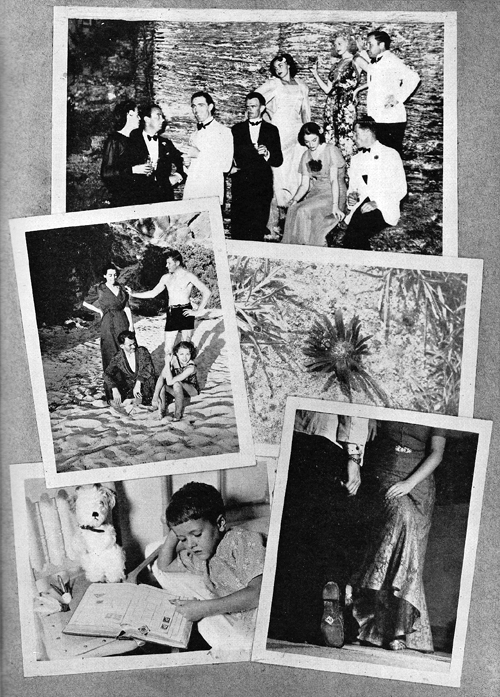

Mason declared that the photos could save time on exposition. Instead of describing the characters and settings, he could just show them. But he didn’t mention that, apart from Allenby, most major characters are introduced in abstract photomontages, not candid snapshots. The first one we see is devoted to wastrel C. Townley Ward. He’s presented in a collage of pictures and news clippings.

The page devoted to Ward could have been replaced with paragraphs of backstory. But the layout coaxes the reader into a process of scrutiny that’s probably more intense than scanning prose. Are there clues in the images or the clippings? This crammed page, coming early in the book, encourages the reader to look carefully at the pictures that follow. This attention wouldn’t necessarily be aroused by traditional drawn or painted illustrations.

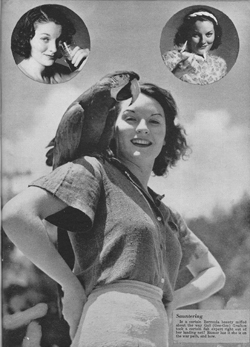

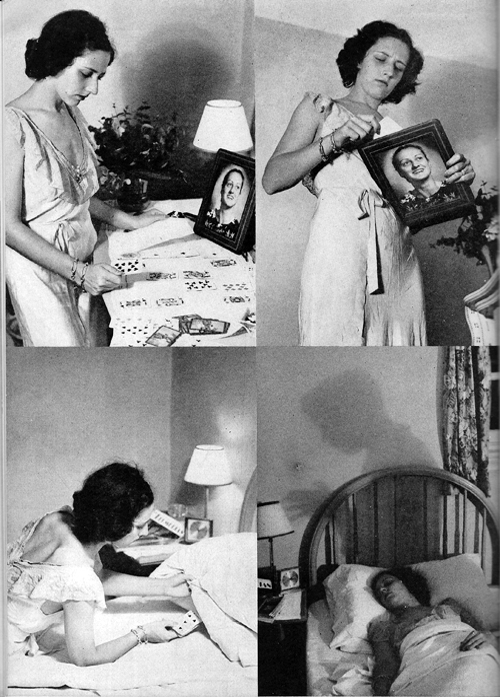

Sometimes, as in the page devoted to jaunty Kathleen Manship, the layout recalls comic-book splash pages.

A second sort of photos accords with Allenby’s restricted viewpoint. He has brought his camera along, so some images, like the nude shot on the beach, are represented as his recording of a crime scene.

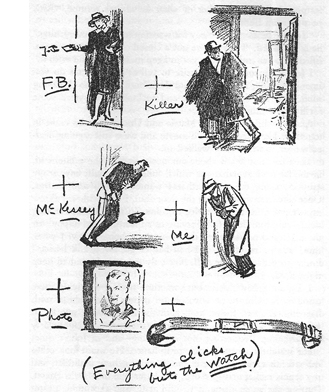

Naturally Allenby films letters and other obvious clues, and he sets traps to gain evidence. He rigs up an automatic camera device to capture an intruder, but to sustain suspense Mason shows us the negative first, then postpones revealing the person exposed (as above).

Sometimes, though, it’s Allenby’s casual snapshots that accidentally capture items whose significance is apparent later. In all, Mason tries to play fair with the reader. If you page back after the solution is revealed, you can find that indeed the clue was there (however tiny). In good mystery-mongering fashion, however, some pages are red herrings. They contain no clues, but you’re likely to study them anyhow.

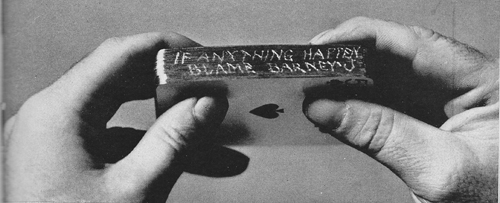

Photography also helps us grasp clues that are more vivid than a prose description could provide. My favorite is the telltale pack of playing cards left behind by Patricia after her death. Trying them out in different sequences, Allenby notices that they contain tiny nicks on their edges. Odd phrases in Judy’s purported suicide note suggest a code the sisters shared, so after cracking that and arranging the cards accordingly, Allenby finds that the nicks yield a message.

I think that the picture makes the discovery livelier than an account in the text would be.

As in many detective stories, the clues are summed up before the detective reveals the solution. Here, Mason gathers up the most relevant photos Allenby has taken, challenging the reader to draw the right conclusions.

Another plot convention: the final assembly of the suspects for a public revelation of guilt. In this book, it’s done through Allenby’s setting a trap. He will take an infrared picture that will, during a crucial moment of darkness, expose the killer. The exercise neatly brings together the objective, omniscient type of photo and Allenby’s eyewitness shots. First we see the entire scene, including Allenby. Then his camera’s record is presented in radically washed-out tones, suggesting a different film stock. (The second frame below is a detail from the climactic two-page spread, to avoid a spoiler.)

Movies on the page

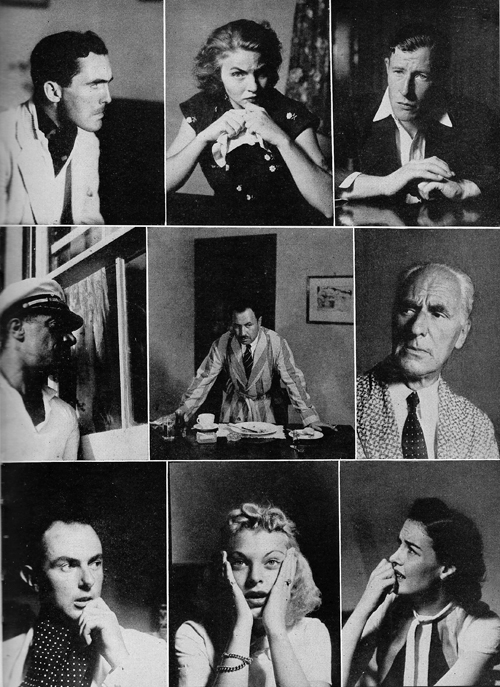

The gimmickry of The Castle Island Case is enlivened by some features that go beyond puzzle and fair play. The book breaks its own rules, sometimes in ways that recall films. For example, we get a cluster of reaction shots of the characters responding to news of Patricia’s death.

The pictorial narration running alongside the text sometimes breaks from our restriction to Allenby’s viewpoint for the sake of a cinematic effect. As he broods on the danger Patricia is in, the book “cuts away” to her in her bedroom. Four images show her sorting the playing cards, slipping the suicide note into a picture frame displaying her sister’s photo, tucking the pack of cards under her pillow, and–ultimate movie touch–sleeping while a clutching shadow hovers over her.

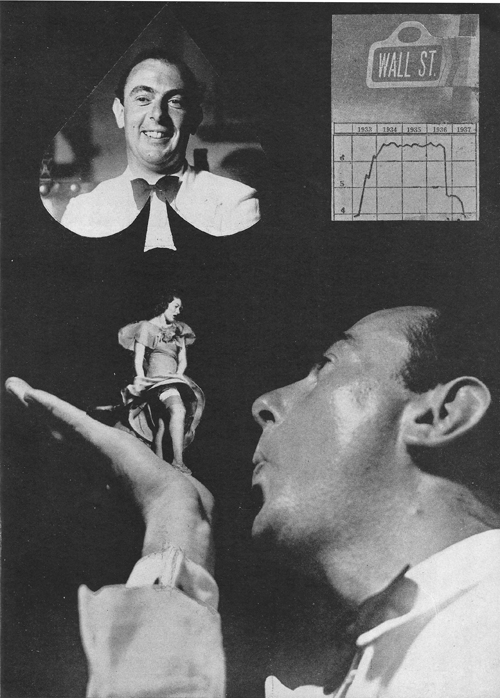

Still later, the book will present a pictorial flashback, complete with angle changes, to show what led to Judy’s disappearance. There’s also a photomontage illustrating Terry James’ freewheeling lifestyle that calls to mind the turbulent montage sequences of Slavko Vorkapich.

The book’s debt to cinema is perhaps most obvious in its last image, a clinch that traditionally closes a Hollywood movie. (See below.) Far stranger is the sequence devoted to the drinks-and-swims party.

One page presents the guests hanging out, with the bottom one suggesting a party snapshot not taken by Allenby, although he’s in it.

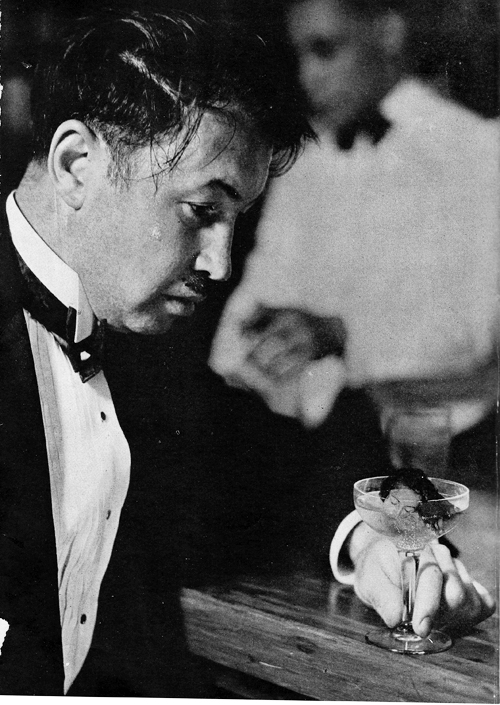

Facing this page is a curious portrait, evidently not taken by Allenby, showing a morose Grafton staring into his drink.

What’s he looking at? Inside the champagne glass is the head of an apparently drowning woman.

Is this a tipoff to the reader that Grafton killed Patricia? At the end we’ll realize what it means, but here it seems to offer a peculiar access to his mind, certainly beyond Allenby’s range of knowledge. In a film, the image might be an abrupt, enigmatic flashback to be explained later. Frozen on the page, and looking so different from the other photos we’ve seen, this hallucination turns into kitsch surrealism.

Nothing ever really goes away. Perhaps the murder dossiers transmogrified during the 1940s into the board game Clue (aka Cluedo). The Wheatley ones were reprinted in the 1980s and apparently caught on for a new generation. The Choose Your Own Adventure children’s books included mysteries that allowed some interactivity, anticipating the branching options of our investigation-driven videogames. And today’s jigsaw puzzle called Alfred Hitchcock is explained:

Alfred Hitchcock isn’t just another jigsaw puzzle – it’s a mystery waiting to be solved. First, read about a psychotic fan who’s obsessed with Hitchcock’s classic films. Next, assemble the puzzle and uncover hidden clues to solve the mystery.

Mason’s “Candid Clue Mystery No. 1” had no successors, but writers didn’t give up on trying to integrate images into mystery plots. Rex Stout tried it, with awkward results, in two Nero Wolfe stories. (One, naturally enough, appeared in Look magazine.) In Murder Draws a Line (1940), Willetta Ann Barber and R. F. Schabelitz divide the labor between a Nick-and-Nora couple. The wife writes the text and the husband, a professional artist, illustrates it with sketches and diagrams of their efforts to solve the crime.

Mason’s “Candid Clue Mystery No. 1” had no successors, but writers didn’t give up on trying to integrate images into mystery plots. Rex Stout tried it, with awkward results, in two Nero Wolfe stories. (One, naturally enough, appeared in Look magazine.) In Murder Draws a Line (1940), Willetta Ann Barber and R. F. Schabelitz divide the labor between a Nick-and-Nora couple. The wife writes the text and the husband, a professional artist, illustrates it with sketches and diagrams of their efforts to solve the crime.

The text-plus-photos books aren’t truly interactive. Nothing we do can adjust the text or create feedback. But they extend the possibilities of a narrative attitude encouraged by the mystery genre.

Classic detective novels and short stories rely on a type of close reading. We’re expected to scrutinize descriptions of locales and behavior for cleverly planted traces of what’s really going on. Agatha Christie has a genius for mentioning items that we read over, thanks to misdirection and the blandness of her prose, but even hardboiled novels bury verbal clues so as to play fair. A slip of the tongue that we probably miss leads Sam Spade to Bridgid O’Shaughnessy’s guilt.

Knowing that authors aim to mislead us through language, we read with a greater degree of suspicion than we bring to other genres. By extending this attitude to images as well as words, gimmicks like The Castle Island Case encourage us to consider how the pictures may tell the story, or sabotage our understanding of it. That’s what movies have done as well. We shouldn’t be surprised that these oddball efforts call on familiar storytelling schemas of classical cinema.

Chapter 17 of Martin Edwards’ splendid The Life of Crime: Unravelling the History of Fiction’s Favorite Genre, reviews many more of these Golden Age games. It’s due out from Collins in May of next year, but in the meantime visit Martin’s bountiful website and proceed to sample any of his vast output of novels, anthologies, and histories of detective fiction.

For background on Cain’s Jawbone, go to this account in The Guardian. It was reissued in 2019, as both a book and a set of cards (now very scarce). The publisher, appropriately called Unbound, offered a prize of £1000 for the first solution. The prize was won by a comedy writer who cracked the puzzle while housebound during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dorothy Sayers’ remark on her Five Red Herrings ploy comes from Janet Hitchman, Such a Strange Lady: A Biography of Dorothy L. Sayers (New York: Avon, 1976), 88-89. The Sayers story using a (very tough) crossword puzzle is “The Fascinating Problem of Uncle Meleager’s Will” (1925).

My quotations from Van Wyck Mason come from “The Camera as a Literary Element,” The Writer 51, 11 (November 1938), 325-326. The review I quoted, unsigned, appeared in “The Criminal Record,” The Saturday Review (9 October 1957), 28.

The Rex Stout Nero Wolfe stories inserting photographs are Where There’s a Will (1940) and “Easter Parade” (1957), reprinted in And Four to Go (1958). I don’t talk about them here.

Thanks to Peter McDonald for introducing me to Virginia, The Shivah, Blackwell Unbound, and other mystery-driven videogames.

P.S. 25 June 2021: Alert reader and old friend Jonathan Kuntz reminded me of other interactive mystery platforms, including the Secret Cinema screenings. He also mentions non-mystery boardgames that let you replay films, as in The Thing and The Lord of the Rings.

P.P.S. 28 June: Alert reader and mystery maestro Mike Grost traces a chain of association to the champagne-glass image. Van Wyck Mason published a story called “The Enemy’s Goal” in Argosy (18 May, 1935). That story was adapted by Joseph H. Lewis for a film, The Spy Ring, released in 1938, and there a character summons up a mental image in a champagne glass. I haven’t seen the film, but Mike suggests that such subjective shots are fairly rare in Lewis films. He thanks Francis M. Nevins for finding the link, and I thank both.

The Castle Island Case (detail).

Five critics, one of them a killer

Goodfellas (1990).

DB here:

Fourteen months of being house-bound gave me plenty of chance to catch up on my reading. But the reading was almost all devoted to the book I was writing on mystery plots in fiction, film, and other media. Now that it has been catapulted out to unwary publisher’s readers, it’s time for me to catch up on some 2020 books I like. In this batch, all have a connection to film criticism, and murder, attempted or consummated, creeps into more than one.

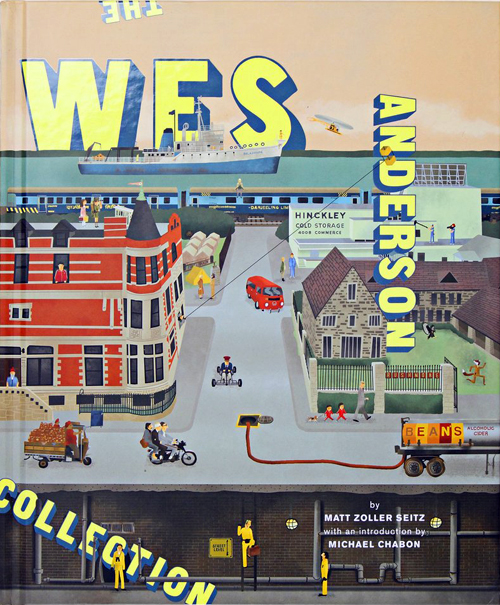

Movies for Muggles

Somebody ought to write a history of the one-movie monograph. Early on there were picture books, and roadshow attractions often produced pretty laminated books as souvenirs, filled with PR stories and color images. My vote for the first analytical monograph would be the very ambitious Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima! (1962). In the early 1970s, American academic presses began offering critical studies of single films; an early example was the FilmGuide series edited by Harry Geduld and Ron Gottesman. (My favorite entry was Jim Naremore‘s study of Psycho.) Since then many publishers have pursued the format, usually as part of a series.

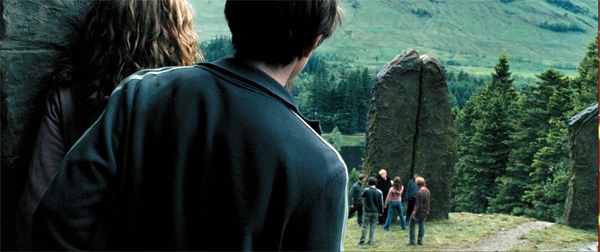

Now we have 21st Century Film Essentials, newly launched at the University of Texas Press. The first two entries are pretty canon-busting. Dana Polan writes on The Lego Movie, and Patrick Keating on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. I haven’t seen Polan’s book, but Keating directly takes up the challenge of the series.

As a franchise film, as a work of digital cinema, as a work of collaborative authorship, and above all as a thoroughly engaging demonstration of the art of storytelling, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is an essential work of twentieth-first century cinema.

I confess I was skeptical, and still am a little. But Keating’s meticulous analysis and interpretation of the film does convince me that this is a ripe example of modern “hyperclassical” cinema. By that I mean a dense, “through-composed” revision of traditional narrative strategies and film techniques, working smoothly together to create effects at many levels. A hyperclassical film is more thoroughly classical than it “needs to be.” In other words, here’s another counterexample to the notion that “post-classical Hollywood” shows a collapse of traditional norms.

I confess I was skeptical, and still am a little. But Keating’s meticulous analysis and interpretation of the film does convince me that this is a ripe example of modern “hyperclassical” cinema. By that I mean a dense, “through-composed” revision of traditional narrative strategies and film techniques, working smoothly together to create effects at many levels. A hyperclassical film is more thoroughly classical than it “needs to be.” In other words, here’s another counterexample to the notion that “post-classical Hollywood” shows a collapse of traditional norms.

Keating’s argument for the film’s richness, I think, revolves around two central concepts. First is that of narrative viewpoint. Virtually all of Azkaban, unlike the earlier entries in the franchise, is filtered through the consciousness of Harry. We’re attached to him as he experiences the action. That doesn’t, Keating hastens to add, make the film radically subjective; indeed, there are relatively few shots from Harry’s optical viewpoint. Attaching the unfolding plot to a character doesn’t rule out a wider perspective, if only because cinema puts him within a wider frame of a shot or an edited sequence. There’s always the possibility of our registering action or other characters’ reactions. The end of the Quidditch flight is thick with these impacted viewpoints, and elsewhere Cuarón’s constantly moving camera nudges us toward implications that supplement, or sometimes contradict, what Harry is concentrating on.

Keating’s other main concept is connected to the broadening of viewpoint: worldbuilding. This idea is obviously central to Rowling’s achievement, as it has been to franchises since Star Wars. But Keating lifts the idea to a central role in how films engage us. The richly realized world of Potter is only an extreme instance of what every narrative does. Borrowing from critic V. F. Perkins, Keating suggests that any film narrative supplies us with the possibility of many stories that are only hinted at, or merely latent.

Most movies prune those secondary offshoots, the better to force us to concentrate on our protagonist. But Tom Stoppard showed that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern deserved their own play. Similarly, franchise films, with the ever-present prospect of sequels, crossovers, or reboots, make us aware that any character, even any item of furniture, secretes a new story, or a bunch of them. The Potter films are committed to this spinoff aesthetic, packing in as many suggestions of sidestories as the screen will bear. This principle finds tangible expression in the portraits jammed into the Gryffindor common room and dorms guarded by the Fat Lady.

Overwhelming us with characters and situations, many in motion, this gallery is perfectly in keeping with English traditions of floor-to-ceiling decor. It’s also a groaning feast of other stories that could yet, somehow, intersect with Harry’s fate. Keating’s shrewd commentary on worldmaking is one of the book’s highlights.

Keating ties these ideas to phases of production and division of labor, reviewing how the novel’s viewpoint and worldbuilding strategies are transposed and extended by script, camerawork, editing, performances, set and costume design, and music. Throughout he weaves what he takes to be the film’s binding theme, that of time. Is the future preordained, as Ms. Trelawney insists in her frantic, fumbling lectures? Or is it open, as Hermoine and others tell Harry? This makes the film’s tour de force climax with the Time Turner into a synthesis of restricted viewpoint (we’re with Harry as he witnesses an alternative future) and worldbuilding (the future is what you make it).

I might quarrel with Keating’s suggestion that the impulse driving Harry’s action is a struggle with the dementers. I saw his relation to Sirius Black as more than the subplot Keating considers it. Overall, though, Keating has produced not only a subtle, supple analysis of the film but also a model for how to understand cinematic storytelling in the age of the blockbuster.

Wiseguy’s progress

If Keating’s book is a classical sonata, Glenn Kenny’s Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas is bop. Keating offers a tidy analysis through crisply defined categories. Kenny provides a hardcopy approximation to a packed DVD.

At the center is a 150 page scene-by-scene account of the film: a commentary track in your hands. Alongside that sit chapters that function as bonus materials. They include a brief introduction to the filmmaker just before he started work on the film, chapters on preproduction, the music (Kenny is an expert on pop and rock), the editing, the critical reception, and the ultimate fate of the real-life protagonist Henry Hill. Then, like the narrator of a Criterion video supplement, Kenny surveys Scorsese’s career after Goodfellas. Finally, an epilogue is virtually a monologue: Scorsese talks almost without interruption for twenty-five pages, as if this were the interview rounding off the disc. There’s also a bibliography, a timeline of the production, and the recipe for Henry Hill’s ziti.

At the center is a 150 page scene-by-scene account of the film: a commentary track in your hands. Alongside that sit chapters that function as bonus materials. They include a brief introduction to the filmmaker just before he started work on the film, chapters on preproduction, the music (Kenny is an expert on pop and rock), the editing, the critical reception, and the ultimate fate of the real-life protagonist Henry Hill. Then, like the narrator of a Criterion video supplement, Kenny surveys Scorsese’s career after Goodfellas. Finally, an epilogue is virtually a monologue: Scorsese talks almost without interruption for twenty-five pages, as if this were the interview rounding off the disc. There’s also a bibliography, a timeline of the production, and the recipe for Henry Hill’s ziti.

It’s overwhelming. Kenny has evidently read everything about the real-life sources of the story, and his interviews turn fan service toward crime reporting. It is no small thing to pursue hard cases who were recruited for bit parts. Kenny has also garnered a lot of information from staff like AD Joseph Reidy, who are seldom given much attention. Keating would probably be happy to see Kenny’s narrative splinter into stories leading to other stories, such as the effects of the film on the careers of Barbara De Fina and Ileanna Douglas.

I compared the book’s central chapter to a DVD commentary. Anybody delivering a voice-over play-by-play regrets that you have to keep up with the film and can’t devote as much time to a big scene as you might like. Thanks to the print format, Kenny is able to pause the film and spiral out from it to fill in backstory or behind-the-scenes dynamics.

Early on, he can give us three pages on Tuddy, both his original (who died in prison) and Frank DiLeo, the actor playing the role. Kenny explains that DiLeo was a music executive who oversaw Michael Jackson’s “Bad” video, which included a Wanted poster of Scorsese in a subway scene, which ties to a sneaky reference to the “Smooth Criminal” video featuring a character named Frank Lideo, played by Joe Pesci. . . well, you get the idea. Likewise, in an astonishing cadenza, Kenny identifies every actor and wiseguy in the long POV tracking shot in the Bamboo Lounge.

His account of the cast rummages through filmographies and personal histories, and adds the sort of oversharing we welcome: “Behind the placid mook mug seen in the movie was a remorseless killer.”

All these exfoliating tales don’t conceal a sustained performance of film criticism. Kenny’s governing idea is that Goodfellas cons us through a bait and switch. Lured in by a rapid-fire opening that arouses a bemused attraction to these bad boys, we’re gradually forced to a more sober, even horrified, realization of their moral and emotional brutality. I think that this fairly reflects most viewers’ experience. But how does the trap work?

Kenny plots an “arc of disengagement” between the killings of Tommy and Spider. A rise-and-fall pattern links the parallel scenes of the Bamboo Lounge, the Copacabana, and the shabby tavern where the gang meets to whack Morrie. Kenny draws nuanced comparisons with The Godfather and is very detailed on Scorsese’s visual techniques, particularly the freeze-frames and fadeouts, which usually get less attention than the flashy camera moves. One of the book’s main points is that Scorsese, newly aware of how TV commercials trained viewers in quick pickup, deliberately decided to make his fastest-paced movie. And of course the music is central to managing our mood and commenting on the story.

As a seasoned reviewer, Kenny can write. “Frisky newlyweds still hot for each other; you love to see it.” Henry (“a walking appetite”) eventually pulls Karen into his schemes: “The revitalized marriage will find its sense of twisted teamwork.” And digression is welcome when it humanizes the author. Listening to Sid Vicious’ version of “My Way” is comparable to “say, eating the fried chicken from the Kansas City restaurant Stroud’s for the first time.” (The “say” makes the sentence.) A movie about food begs the critic to sample a little synaesthesia, with music evoking mouth-watering chicken. Come to think of it, that linkage of music and food is in Goodfellas too.

I especially enjoyed Kenny’s rebuke to fans who bust this carefully constructed work into “movie moments.” You probably know that one school of criticism thinks that films are more or less loose assemblages of scenes, out of which certain instants become incandescent. Certainly there are such moments in many movies, and sometimes they stand out from a gray pudding. But often strong moments ravish us because they’ve been prepared for by careful craft. So Kenny’s guided tour of Goodfellas shows its affinities with Keating’s holistic approach:

Serrano and his crew reduce movies to anthologies of “cool” or shocking moments, as opposed to fictions whose circumscribed worlds aspire to create beauty or sorrow or horror or joy in some formally coherent whole.

Mon semblable, mon frère.

Dead end at the ocean’s edge

La La Land (2016).

On the other hand, I ought to be out of sympathy with Mick LaSalle’s Dream State: California in the Movies. It’s unabashedly reflectionist, tracing how films project contradictory images of the Golden State. The screen image of California promises pure self-fulfillment, but that leads to loneliness, danger, conformity, and loss of dignity. If Kenny and Keating see movies as made by an army of artisans, LaSalle treats them as springing full-blown from American mythology. There is barely a mention of a director, let alone a sound mixer, in his account.

Instead, California-ism makes its way to the screen through a surge of a “collective mentality.” For instance, the blockbusters’ endless images of urban annihilation spring from “a people disseminating and celebrating visions of their own obliteration. . . . Something is seriously wrong with the nation producing such visions.” He suggests that “the fear of extraterrestrials is the disguised fear of illegal aliens. . . . the fear of the apocalypse is the disguised fear of terrorism.” Hollywood takes dictation from mass anxieties.

Instead, California-ism makes its way to the screen through a surge of a “collective mentality.” For instance, the blockbusters’ endless images of urban annihilation spring from “a people disseminating and celebrating visions of their own obliteration. . . . Something is seriously wrong with the nation producing such visions.” He suggests that “the fear of extraterrestrials is the disguised fear of illegal aliens. . . . the fear of the apocalypse is the disguised fear of terrorism.” Hollywood takes dictation from mass anxieties.

I’ve explained elsewhere (here and here) why I find such claims unpersuasive. I think that reflectionism is every smart person’s mistaken idea about cinema. But sometimes, as with Susan Sontag’s essay “The Imagination of Disaster,” a reflectionist account of a film can activate some valuable ideas and information along the way, and it can host some entertaining writing. These benefits, I think, emerge throughout Dream State. In kaleidoscopic bursts, LaSalle provides suggestive takes on movies familiar and obscure, and the way they link to one another.

For example, he tracks recurring plot patterns. There’s California’s version of the One Great Night, when individual transformation takes place in a few hours of turbid activity (Superbad, Modern Girls). American Graffiti is the prototype, and in just two pages LaSalle evokes the way audience knowledge races ahead of the characters, far into the future. (Curt winds up in Canada, which probably has to be explained to young viewers today.)He’s very good on the cost-of-stardom plot, from What Price Hollywood to La La Land, this last the only film that faces the fact “that every great advance requires sacrifice, and that even though there is nothing like the joy of first love , there is nothing more important than the fulfillment of one’s inner self.”

LaSalle considers our willingness to take stars as surrogates for us, and here I was reminded of another critic who tried to pierce the Hollywood Hallucination, the great Parker Tyler. He had, I think, a more meta attitude toward the movies, since he avoided straight reflectionism by treating every film as a charade, a narcissistic exercise in make-believe. For Tyler, Hollywood movies were always primarily about Hollywood, filled with symbolic surrogates for their makers and their viewers. In this respect, LaSalle’s opening chapter is agreeably Tyleresque, positing The Wizard of Oz as a film enacting the flight to a dream city; the Emerald City as Hollywood. Like Tyler as well, LaSalle searches for what he calls a movie’s complex finish, as with a glass of wine. Wizard ends not on a note of ambiguity exactly, but on something like a chord that sets off contrary overtones. Tyler’s books were built on this chord.

LaSalle considers our willingness to take stars as surrogates for us, and here I was reminded of another critic who tried to pierce the Hollywood Hallucination, the great Parker Tyler. He had, I think, a more meta attitude toward the movies, since he avoided straight reflectionism by treating every film as a charade, a narcissistic exercise in make-believe. For Tyler, Hollywood movies were always primarily about Hollywood, filled with symbolic surrogates for their makers and their viewers. In this respect, LaSalle’s opening chapter is agreeably Tyleresque, positing The Wizard of Oz as a film enacting the flight to a dream city; the Emerald City as Hollywood. Like Tyler as well, LaSalle searches for what he calls a movie’s complex finish, as with a glass of wine. Wizard ends not on a note of ambiguity exactly, but on something like a chord that sets off contrary overtones. Tyler’s books were built on this chord.

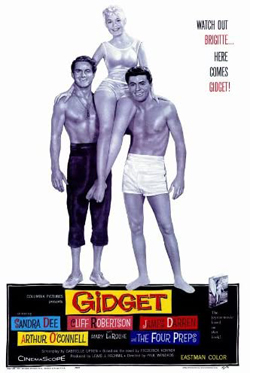

Another critical avenue that LaSalle opened up for me was iconographic: the differences between LA movies and San Francisco movies. He deftly contrasts the ambience and topography of the cities. Noir and disaster films are primarily anchored in LA, while San Franciso movies tend to be steeped in nostalgia (e.g., Jobs, Milk). He keeps finding new angles to comment on. Avoiding the obvious effort to discuss California’s boom during and after the war, he skips back to the months around Pearl Harbor to bring to light films, mostly exploitation quickies like Secret Agent of Japan and Little Tokyo, USA, that rushed to treat Japanese Americans as potential spies. Meanwhile, the unoffending citizens were shipped off to internment. On a lighter note, anybody who’s bold enough to praise Gidget as a more mature film than Easy Rider gets my admiration (and agreement).

LaSalle, who came to California from the east, weaves in bits of memoir that highlight his main theme. And like Kenny, he writes with conversational wit.

“Home is horrible. Oz is horrible, too. . . but at least it’s in color.”

On Saturday Night Fever and Grease: “One seems tough, but it’s soft. (Of course, that’s the New York film.) One seems soft, but it’s hard. (Of course, that’s the Los Angeles film.)”

In Hollywood “integrity is so original it might just work as a strategy.”

In Out of the Past, “sex can kill you, but it’s worth it anyway.”

In San Francisco (1936) “if only to get Jeanette MacDonald to stop singing, the Earth had to intervene.”

Contrasting Monterey Pop to Woodstock‘s utopian fantasy, LaSalle nearly had me on the floor.

This is a model? Hundreds of thousands of intoxicated people, unable to wash, all but sitting in their own slop, cheering for a series of aristocrats that swoop down to entertain them and then leave? Meanwhile, the army flies in food and the slave classes clean out the Port-O-Sans? That’s sustainable as a societal model?

In addition to all this, through engaging appreciation, LaSalle has prompted me to seek out a great many films I hadn’t heard of. That’s another duty of the good critic. After seeing so much–pounding the beat every day–the movie reviewer can steer you to new discoveries.

Cinephile into cineaste and back again

He Said, She Said (1991).

All of these critics have participated in filmmaking. Mick LaSalle has written and produced documentaries. Glenn Kenny has been an actor in several films (including Soderbergh’s Girlfriend Experience). Patrick Keating, who has an MFA in cinematography, has been a DP on independent projects. Reciprocally, director Ken Kwapis started out wanting to be a film critic–in third grade, no less.

In college he devoured classic movies and gorged on film criticism. Kwapis went on to become a director of consequence, overseeing many features (Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, He’s Just Not That into You) and TV episodes (The Garry Shandling Show, The Office). Yet he didn’t leave his cinephilia behind. But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct: Lessons from a Life behind the Camera has an intellectual heft rare in career memoirs and moviemaking manuals. It’s at once thoughtful and practical, suffused throughout by an ethic of modesty, tenacity, and what I can only call a desire to remain both a good artist and a decent person. It also contains some first-rate film criticism.

In college he devoured classic movies and gorged on film criticism. Kwapis went on to become a director of consequence, overseeing many features (Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, He’s Just Not That into You) and TV episodes (The Garry Shandling Show, The Office). Yet he didn’t leave his cinephilia behind. But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct: Lessons from a Life behind the Camera has an intellectual heft rare in career memoirs and moviemaking manuals. It’s at once thoughtful and practical, suffused throughout by an ethic of modesty, tenacity, and what I can only call a desire to remain both a good artist and a decent person. It also contains some first-rate film criticism.

Kwapis intercuts three sorts of chapters. There is the chronological account of the filmmaking process, with advice on taking meetings, establishing rapport on the set, giving actors “playable notes,” and coping with postproduction and marketing. Kwapis insists at every turn that you need to be both firm and flexible, open to every suggestion from the production team but still adhering to your conception of the project.

But this is not auteurism on steroids. If you’re not a Spielberg or a Nolan, the director has to learn tact and strategy. Kwapis emphasizes not abstract technique but the interactive, interpersonal demands of filmmaking, He suggests ways of responding to producers’ notes or actors’ complaints that allow everyone to keep their dignity. Just stepping away from the Video Village, that cluster of people around the monitor, and positioning yourself by the lens is a way of proactively steering the scene. He even gives good advice about bad reviews. His creative process? “I want to stand behind the camera and make sure there’s something alive going on in front of it, something recognizably human.”

A second batch of chapters shows this aesthetic/ethos in action through case studies from Kwapis’ career. Starting with Follow That Bird (1985), the Big Bird movie, and running up to A Walk in the Woods (2015), these chapters are about concrete problem-solving. How do you direct puppets? Or orangutans? Or Rip Torn? How do you support an actor who’s just not physically up to the role? There’s a fascinating account of staging options in The Office, where different situations force choices between developing the action in the “bull pen” or in the conference room.

The 1990s were rife with narrative experiments, and He Said, She Said (1991) was one of them. Unfolding over two days, its first part uses flashbacks to present Dan’s memory of his romance with Lorie, while the second part shifts to her version, with replays and gap-filling scenes that show the biases of his account. Kwapis and his wife Marisa Silver (Permanent Record) decided to divide responsibilities, with him directing the man’s scenes and her directing the woman’s. They also built in stylistic differences.

We pre-visualized each version to create as much contrast between Lorie’s and Dan’s personaities as possible. For example, I often show Dan’s literal point of view of Lorie, while Marisa uses camera movement and choreography to underscore how Lorie feels about herself (i.e., insecure).

They created specific ground rules for shooting the scenes. Kwapis’ portion came first, so that Silver could see it and fine-tune the replay. Kwapis is admirably specific about how their strategy shaped performance and plot, with minor characters in one half becoming major in the second.

In other words, a cinephiliac idea. (Kwapis prepared for his task by watching Rashomon, The Killing, and Citizen Kane.) The third type of chapter he offers is pure, sharp film criticism, always informed by the demands of craft. His account of American Graffiti is quite different from LaSalle’s, but no less appealing, emphasizing Curt’s visit to Wolfman Jack as an epiphany that needs no formal underlining (“no ham-fisted push-in”).

Other chapters scrutinize 2001, Lawrence of Arabia, The Graduate, I Vitelloni, and other classics. Without being pretentious Kwapis manages to invoke the “objective correlative” (e.g., shoes in Jojo Rabbit) and reflexivity (no big deal). I especially appreciated his detailed analysis of staging in a scene often overlooked in The Magnificent Ambersons: George’s confrontation with a gossipy neighbor, handled in one deftly choreographed close framing.

Kwapis designed the book to explore these three dimensions, but he isn’t puritanical about keeping them apart. Case studies and problem-solving pop up in the general advice sections, and the critical acumen shines through even brief examples of on-set tips (e.g., decisions about a score for Traveling Pants). It all flows together.

The result ranks with Sidney Lumet’s Making Movies and Alexander MacKendrick’s On Film-Making, the most acute personal reflections on Hollywood directing. But like those, it’s more than a testament to the power of craft. It’s also a vision of how, as the first chapter says, to go “beyond success and failure in Hollywood.” You do it, Kwapis maintains, by knowing your plan, respecting your co-workers, inviting discovery through accidents, and staying humane. I like to think that studying films as a critic helped him get there. Not every director, after all, can quote Jean Renoir.

“Only a hack cares about the goddam script”

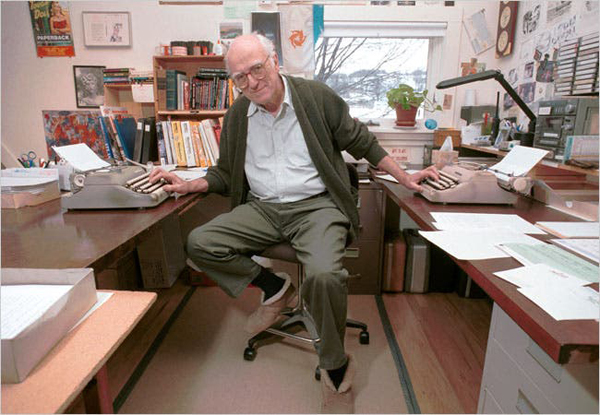

Donald Westlake (David Jennings for the New York Times).

I promised you a murderer, and he arrives in Donald E. Westlake’s Double Feature, a pair of novellas originally published as Enough (1977). The second, Ordo, takes place in Hollywood, when a sailor learns that his first wife has become a movie star and decides to look her up. It’s remarkable in several ways, but the story that grabbed me was A Travesty. On the first page a film critic kills his girlfriend.

True, it’s an accident, but even then he seems less distressed than he should be. He wipes down the crime scene and slips out. Of course he becomes a suspect. Once he seems to be cleared, the trusting cop lets him mosey along on later investigations. They discover that the critic has a knack for solving crimes, including an old-fashioned locked-room puzzle. He gets caught thanks to a plot twist that owes a good deal to Westlake’s early days writing happily overblown softcore porn.