Archive for December 2006

Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun

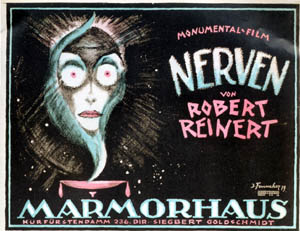

1. “It hypnotizes the viewer,” writes Paul van Yperen of the Nerven poster he printed in the new issue of the Dutch journal Skrien. Paul sent it to me because I wrote about Robert Reinert’s film in my forthcoming collection of essays, Poetics of Cinema. Nerven is a disorienting, highly experimental work. Released in 1919, before The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (early 1920), it might have become a prototype of German Expressionist cinema if it had been widely seen and preserved by archives. Nerven, along with Reinert’s other major film Opium (1919) would make a wonderful twofer on a DVD release.

2. We’ve set up an archival supplement to our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction elsewhere on this site. It includes analyses that appeared in earlier editions but were cut for reasons of space or film availability.

The pieces discuss Stagecoach, Hannah and Her Sisters, Desperately Seeking Susan, Day of Wrath, Last Year at Marienbad, Innocence Unprotected, Disney’s Clock Cleaners, Tout va bien, High School, and Hitchcock’s first Man Who Knew Too Much. DVD has made nearly all of these films easily accessible, so we hope reviving the essays will be of use to students and free-ranging viewers.

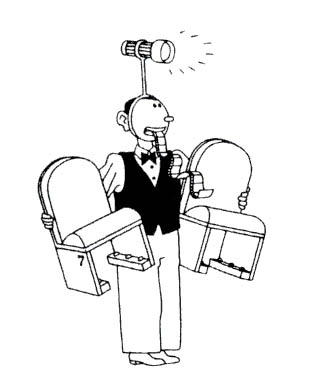

3. Check out the nifty interview with Joost Swarte in the new issue of The Comics Journal. Excerpts are here.

Swarte is the greatest heir to the Belgian-Dutch “clear-line” style, and his witty cartoons have become worldwide classics. Kristin and I have been collecting Swarte books and posters since the 1980s, although as his projects have expanded to building design his output of images has waned (except for the occasional item for The New Yorker).

Swarte has much to say about Hergé’s mastery of visual storytelling, claiming that the Tintin tales are like little movies.

Swarte has much to say about Hergé’s mastery of visual storytelling, claiming that the Tintin tales are like little movies.

He was very much influenced by cinematographic laws. Where do you place your camera? Is the hero always coming from the left? What’s the relation between foreground and background? All sorts of terms that he used come from cinema.

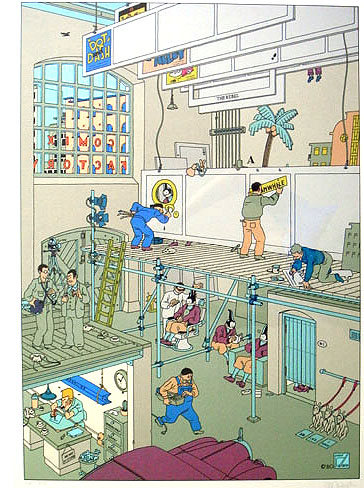

Swarte too has an affinity for film. One of his best pictures, Comic Factory, treats cartooning as if it were moviemaking. Our cartoonist labors in lower left, the girder of a deadline hanging above him, while a producer (with cigar) seems to be telling the photographer how to shoot the panels. Jopo de Pojo gets spruced up for his close-up while his doubles (or clones) lounge around. Set designers and scene painters labor over the panels.

Swarte’s teeming street scenes, usually including dog turds, are filled with glimpsed gags in the manner of Tati. Not surprising, then, that under the skilful questioning of David Peniston, he confesses his admiration for Play Time. New collections of Swarte’s comics are apparently forthcoming, in several languages, in 2007. By the way, the same issue of the Journal has a nice appreciation of Cliff Sterrett, another comics genius, creator of the amiable, lovely, and quite nuts Polly and Her Pals. Click here for a nice blow-up sample.

4. Speaking of cinema in still images: One of Eisenstein’s favorite pastimes was to find anticipations of film in earlier media. He loved the fact that Myron’s discus thrower was portrayed in an impossible position, with the limbs indicating different phases of the action.

This and similar items were inspirations for the plate-smashing scene in Potemkin.

So in a holiday spirit, I’d ask: what would Eisenstein have made of this painting, which I saw again last summer in London’s National Gallery–Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity of 1501?

Reproduction, especially this tiny, doesn’t do the picture justice, but you should be able to see how the symmetry of the composition is broken by the slope up to the central scene of Mary and the mule bending over the baby. As with Swarte cityscapes, there’s a lot to dig for. Angels on left and right of the manger direct the Magi to the main action, and in the lower section angels kiss men while devils dive into the fissures of the earth.

Key for students of cinema, though, is the whirling dance of the angels in the upper third of the picture. Strictly speaking, they all seem out of step, no two in sync. But then you notice that each is executing a slightly different phase of one continuous movement, as if Muybridge had captured a single dancer’s circling trajectory with his early stop-motion photography. Angel Locomotion, he might have called it; but Botticelli got there before him.

Word by word

DB here:

This year two prominent fiction writers opened their workshops to us. Jane Smiley’s Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel, published by Knopf last spring, is a compendium of information and wisdom, offering thirteen substantial chapters on technique followed by lively essays on 101 novels. Written in the aftermath of 9/11, the book is a testament to the joys and consolations of literature.

Smiley offers a feast of ideas and examples. She observes that in a novel, the protagonist tends to contrast his or her fate with those of others. She shows how a novel’s rhythm is created by alternating passages of action and reflection, with each shaping the other. She also remarks on the novel as a type of game:

The game quality of the novel gives it meaning and form, because all games begin, have a playing time, and end. It also gives the novel at least a rudimentary raison d’etre, since games are a recognized form of learning for young mammals. The author sets up the game and is required to signal to the reader early in the narrative what the rules are.

With her top-101 list, Smiley isn’t proposing a canon. Her inspiring essays are at once historical (moving from The Tale of Genji to Jennifer Egan’s Look at Me) and very pluralistic. On her list we find both Dickens and Wilkie Collins, Scott Fitzgerald and P. G. Wodehouse, Muriel Spark and Garrison Keillor.

Now we have Francine Prose’s Reading Like a Writer: A Guide for People Who Love Books and for Those Who Want to Write Them (HarperCollins). This too is wonderful, but in a rather different way. Smiley’s book is a doorstop, Prose’s can be slipped into a carry-on. Although Prose discusses several novels, she seems most at home with the short story. Smiley is happy to generalize, exploring broad claims in a reassuring but rigorous way. Prose, a child of New Criticism and the practices of close reading, backs away from generalizations and relies on abundant quotation to develop her points. It’s a conservatory approach. We study the masterworks (high and low–you’ll find Chandler and John Le Carré here) and through delicate discrimination we learn to admire good writing and see how we might develop a supple style ourselves.

Jane Smiley believes that fiction rests on some basic precepts (not rules): craft premises, tacit contracts with readers, assumptions about how genres work. In one chapter she sweeps across theories of fiction from Aristotle to Henry James, harvesting the enduring ideas. Prose’s book is more tentative; she treats even craft precepts as loose guidelines, always subject to revision.

In her skin-prickling penultimate chapter, Prose recounts a series of craft tips that she gave her students. Motivate your characters’ action! Don’t give two of them similar names! Then she shows how reading Chekhov made her doubt each homily.

And this is what I’ve come to think about what I learned and what I taught and what I should have taught. Wait! I should have said to the class. Come back! I’ve made a mistake. Forget observation, consciousness, clear-sightedness. Forget about life. Read Chekhov, read the stories straight through. Admit that you understand nothing of life, nothing of what you see. Then go out and look at the world.

With her admiration for Chekhov, Babel, and Nabokov, Prose advances the case that exacting attention to style isn’t a flight into artifice but the best way of teasing out the nuances of human life.

Every writer should read her first few chapters. In “Words” she lays down the book’s premise: “It’s essential to slow down and read every word. . . Ask yourself what sort of information each word–each word choice–is conveying.” She warns against reading fiction in order to skim off themes or psychological insights, especially when “crucial revelations are in the spaces between words, in what has been left out.”

The next chapter, on sentences, is one of the best statements I’ve ever read about the craft of writing. A young writer, Prose reports, once told his agent that he wanted above all to write “really great sentences.” She raises the curtain on professional gossip: it turns out that writers love to talk about sentences. (How many writers of academic prose even think about their sentences, let alone discuss them with others?) She champions the lost skill of sentence diagramming, and I was happy to learn that she encourages a habit of mine, that of keeping close at hand books by writers who compose admirable sentences.

The following chapter was especially enlightening to me because I’m struggling to find more varied ways to paragraph my writing. Prose examines the killer moment in Rex Stout’s Plot It Yourself when Nero Wolfe explains that the pattern of a writer’s paragraphs is a stylistic fingerprint. She fastens on a passage I’ve always loved, in which the narrator, Archie Goodwin, enacts in print what his boss has proposed. Across a long paragraph, Archie spends “about half an hour studying paragraphing,” while recapping the routines of the Wolfe household. He ends:

The following chapter was especially enlightening to me because I’m struggling to find more varied ways to paragraph my writing. Prose examines the killer moment in Rex Stout’s Plot It Yourself when Nero Wolfe explains that the pattern of a writer’s paragraphs is a stylistic fingerprint. She fastens on a passage I’ve always loved, in which the narrator, Archie Goodwin, enacts in print what his boss has proposed. Across a long paragraph, Archie spends “about half an hour studying paragraphing,” while recapping the routines of the Wolfe household. He ends:

The next sentence is to be, “But the table-load of paper, being in the office, was clearly up to me,” and I have to decide whether to put it here or start a new paragraph with it. You see how subtle it is. Paragraph it yourself.

I stood surveying the stacks of paper.

(Robbe-Grillet, eat your heart out.) Prose goes on to explore various ways in which Archie might have broken up his long stretch of description. For now and hereafter, she is my Goddess of the Paragraph Break. Or should I have made that last sentence a separate paragraph?

The rest of the book, covering detail, narration, and other techniques, is no less enlightening. Reading Like a Writer winds to a conclusion in which, after the encomium to Chekhov, Prose asks all writers to summon the courage to avoid easy tricks, to treat their work with integrity, and to follow language where it leads. Her last extract, revealingly, comes from verse. Her insistence on the words on the page, I came to see, amounts to treating prose as if it were poetry.

One moment of doubt, though. It’s generally realized that many writers are story people rather than style people. Dreiser and Stephen King have a penchant for awkward writing. Often their style records their struggles to find the right phrase. Yet once you’re hooked, you’re hooked and their stories carry you forward. Maybe Prose would argue that their books would be even better if they wrote better; or maybe the novel is a more forgiving genre than the short story. Anyhow, neither writer is Chekhov. Still, it’s indicative that unlike Smiley’s 13 Ways and virtually every other writing manual, Prose’s book offers no guidance on plot or structure. This is a book about style–its techniques and its ethics.

Why bring these considerations into this blog? For one thing, students of cinema should always be open to learning about form and style in other arts. Reflections on literary point of view can alert us to how filmmakers manage it. Prose suggests that point of view is subtler than “who speaks?” and “who sees?” Word choice and sentence rhythm can tip a scene from one character to another without any use of I said or she noticed. That set me thinking. Does cinema have something similar? In film, if we show one character in longer-held shots than others, does that help weight the scene to her? Or might we have her advance toward the camera when the others stay behind? Or could we modulate the sound levels to bring her voice into prominence? Reading about techniques in the other arts can sharpen our awareness of parallels or non-equivalences between other media and film.

Prose’s book is also part of a heartening trend in the humanities. The growing success of literary-appreciation books for a general audience over the last few years may signal the flagging of the sort of Grand Theory promoted by Structuralism, Post-Structuralism, and other movements. Smiley the pluralist flirts with some academic terminology, but Prose is uneasy with academic theory. When she went to graduate school

I soon found that my love for books was unshared by many of my classmates and professors. I found it hard to understand what they did love. . . . That was when literary academia split into warring camps of deconstructionists, Marxists, feminists, and so forth, all battling for the right to tell students that they were reading “texts” in which ideas and politics trumped what the writer had actually written.

On the whole, I think, Prose’s skepticism has been borne out. The fact that Harold Bloom, Stephen Greenblatt, and other eminences of High Theory are now writing books teaching general readers to, well, enjoy great literature shows that radical ideas have been dialed back quite a bit. The very title of Marjorie Garber’s Shakespeare After All seems, against all worries about canonization, to resurrect the idea of The Greatest Writer Who Ever Lived.

There are more practical reasons to consider books like Smiley’s and Prose’s in this forum. Many readers of the Internets are writers. They write school essays, journalistic pieces, professional papers, blogs, and all manner of things. Most of us are artisans of language, and we ought to welcome coaching from experts. I used to tell my graduate students that whatever they thought they were going to be–scholars, researchers, archivists, teachers–they would all be professional writers. We ought to be as mindful about the craft and duties of writing as we are about any other aspect of our calling.

Finally, Prose indirectly reminds us of the importance of peering closely at the texture of movies. It’s not only strong stories and provocative themes that draw us to cinema. The moment-by-moment fluctuations of what we see and hear on the screen also shape our experience.

Finally, Prose indirectly reminds us of the importance of peering closely at the texture of movies. It’s not only strong stories and provocative themes that draw us to cinema. The moment-by-moment fluctuations of what we see and hear on the screen also shape our experience.

One important thing that we can learn by reading slowly is the seemingly obvious but oddly underappreciated fact that language is the medium we use in much the same way a composer uses notes, the way a painter uses paint. I realize it may seem obvious, but it’s surprising how easily we lose sight of the fact that words are the raw material out of which literature is crafted.

In the last sentence, substitute images and sounds for words, and cinema for literature, and you have an earnest reminder that we should look and listen closely to movies.

Despite all we know about film technique, the systematic study of film style is really just beginning. By reading literature as Prose recommends, we not only get more out of great books; we cultivate skills that can enrich our understanding of film.

Lewis Klahr X 3, X 4

DB here:

Last Saturday Lewis Klahr came to Madison, brought by the Starlight Cinema group of the University’s Student Union. He showed two sets of films: The Two Minutes to Zero Trilogy (2003-2004) and Daylight Moon (A Quartet) (2002-2004). He’s one of the most gifted collage animators in the American avant-garde, surely the most accomplished since Larry Jordan. Both filmmakers work in the Surrealist tradition, but Jordan seems more drawn to images from nineteenth-century illustration, while Klahr loves US pop culture. As a baby boomer who came of age in the 1970s, he recycles magazine ads, comic books, and book illustrations in lyrical and sometimes aggressive ways.

Tipped off by Tom Gunning, I first encountered Klahr’s work in The Pharoah’s Belt (1993), his most famous film. I also enjoyed seeing his film-within-a-film in Miguel Almereyda’s imaginative Hamlet (2000). At a recent Hong Kong International Film Festival I saw The Two Minutes to Zero Trilogy and decided to study it a bit. I contacted Klahr and he kindly sent me the film, along with Daylight Moon, and some lovely work by Janie Geiser, an accomplished filmmaker in her own right. You can get examples of their work on this DVD from Craig Baldwin (himself an extraordinary filmmaker).

Seeing the Trilogy again, I was even more impressed by it. Each of its three parts consists of images snipped out of old 77 Sunset Strip comic books, with each part implying a bank holdup and a chase, but each time the events are compressed more and more. The last episode runs only one minute. “A feature length narrative compressed 3 different times into 3 separate films of diminishing duration until the synoptic is synopsized,” as Klahr puts it.

Don’t try to find a plot. Each episode uses just enough cops-and-crooks iconography to tease us into trying to create a coherent narrative, but it frustrates that in several ways. The images refuse to settle down, slipping and snicking past your eye in an imitation of saccadic glances. The microscopically short snippets recall multitrack sampling. In the Madison Q and A, Klahr called it a “pan and scan aesthetic.”

Sometimes the cartoon panels jerking past the camera create a weird effect of motion. A man dodging into a car with a valise seems to be whizzing off, a woman seems–for only one frame–to wave a sheaf of bills.

The cutting is rapid-fire as well. I’d thought that Klahr had edited in the camera, but he spliced everything. A certain maniacal precision becomes evident when you can actually look at the images on the strip and see the bold shot-changes, like the one crowning this post. The trilogy evokes the rush of a heist film without ever giving us more than glimpses of what the narrative might be. The sense of action hurtling toward chaos is cranked up by soundtracks using roaring guitar music from Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca.

Daylight Moon (A Quartet) was far more relaxed. I saw it as a meditation on childhood and its sensitivities, fears, and moments of awe and mystery. (A touch of Joseph Cornell, maybe.) Valise is dominated by the vastness of our planet and the cosmos; Hard Green gives us comic-book imagery of military combat. Soft Ticket was a lyrical remembrance of baseball cards, and the finale, Daylight Moon blended imagery of kid culture and suburban utopias with the soundtrack of Night of the Hunter.

Klahr talked about the quartet as “the best film I’m ever likely to make,” largely because it achieved his aim of a “democracy of subjectivity.” He meant by this the poetic power of the juxtapositions he creates, which invite viewers to connect the material in unpredictable ways. Hollywood films, he remarked, try to get us all to experience the material in a single way, and that’s suitable for a mass audience. But collage films like his have a “signal to noise ratio” that allows viewers to tune in to something, drop out for a few moments, and then tune in again.

For each viewer, the high-information moments will be different, and if a viewer returns to the film, he or she will probably find new images to focus on. This time through the Quartet, I noticed that each of the first three films had a recurring male figure–a sea diver/ astronaut, a soldier, baseball players–until Daylight Moon ends with a man stretched out on a used car. This would seem to be a reverie about a boy’s childhood.

Klahr is a warm, unpretentious speaker and he engaged the audience in a lively dialogue. His work deserves to be more widely known. I can’t imagine watching the Trilogy on DVD; could digital sampling capture the REM effects of the blurring pans? Still, a release on that format would surely expand his circle of admirers.

Film educators no longer criminals

Kristin here—

The rise of digital media has made the unauthorized copying of intellectual property easy. That, of course, drives the producers of that material crazy. We all know that the entertainment industry is said to be losing billions of dollars world wide from various sorts of piracy, from the sale of bootleg DVDs in southeast Asia to the downloading of sounds and images from the internet.

Much of this activity is undoubtedly illegal and undoubtedly violates entertainment producers’ copyright. But in trying to stem the tide of piracy, the industry hasn’t just gone after the wrongdoers. It has encouraged Congress to make more and more uses of intellectual property illegal, in the process riding roughshod over the Fair Use provision in the United States Code. A brilliant way to stamp out crime: make more activities into crimes and hence have more criminals to pursue. You’d think they have enough problems just going after the real pirates. But people like educators and scholars who try to use clips from movies in their classes or frame enlargements as illustrations in articles and books were thrown into the general mix of copyright violators.

That happened in 1998, when the Digital Millennium Copyright Act was signed into law by Bill Clinton. It essentially made any copying of visual or sonic material that involved breaking a digital encryption code illegal. All sorts of means exist to break these codes. Programs exist to grab frames from movies on DVD. Fans can post images on their websites (thereby offering the studios free publicity). Professors can import frames into their Powerpoint-based lectures. Scholars can illustrate their articles and books with reasonably high-quality images. The devising of such programs and the activities just mentioned were all illegal under the DMCA.

(For the Copyright Office’s own summary of the act, go here; for the Wikipedia summary, here.)

In the 1970s, when David and I were setting out to write Film Art and our other early books, we faced a similar issue, though at that time the copyright law concerning the use of frame enlargements was far less clear. Film studies was still a young field. Most publications on cinema, whether textbook or scholarly article, used studio-generated publicity photos as illustrations. We reasoned that such images did not reflect what really appeared in the film, since they were still photos taken on the set, often with different poses, lighting, and camera position. They were useless for the sort of close analysis we wanted to do.

Film Art thus became the first introductory film text to use frame enlargements extensively. Our publishers accepted the idea that such illustrations fell under fair use. Other publishers, however, were nervous about the idea. Did reproducing frames violate copyright? Editors weren’t always willing to risk finding out the hard way. Some authors paid large “permissions” fees to reproduce frames. Others gave up and settled for production stills.

Around 1990 I was asked by the Society for Cinema Studies (now the Society for Film and Media Studies) to chair a committee to investigate the validity of Fair Use as applied to film images. The result was the “Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Society For Cinema Studies, ’Fair Usage Publication of Film Stills’” (1993). This report established that fair use most probably applied to film frames, and educators and scholars were not violating copyright when they used slides or illustrations photographed from the original film. Several presses changed their policies as a result of the report, no longer requiring their authors to obtain unnecessary permissions for frame reproductions. The use of frame enlargements in scholarly publications spread, and film studies benefited as more authentic and useful images were employed by scholars.

Happy ending, right? Certainly the studios never sued over frame enlargements, before or after the report. In fact, relatively few authors were using frame enlargements. It took special equipment to photograph such frames: expensive camera attachments, color-balanced light sources, and the expertise to use both. Those of us publishing extensively illustrated books on Ozu or Eisenstein weren’t exactly a concern to the film industry. In fact, studio executives probably didn’t know that we existed and wouldn’t care if they had.

Then along came DVDs, which made frame grabbing easy. Scholars who had never bothered to get the special equipment or learn how to photograph film frames suddenly could quickly pull images for use in their publications. The reliance on publicity stills declined further. Frames were everywhere, all presumably covered by the same Fair Use law that 1993 report had opined applied to the reproduction of film frames. Legitimate users of frames had to get around the encryption codes, but like millions of DVD users around the world, most of them were savvy enough to do so.

I’m sure that the DMCA was not envisioned as applying to film scholars seizing frames for their publications or professors using visual examples in classes. Still, the provisions of the act were so broad that suddenly scholars and educators were criminalized for doing what they needed to do to foster knowledge: show clips from DVDs in lectures and use frame enlargements from DVDs in books and articles. They had to get around the studios’ codes that prevented piracy. Many of us went ahead and broke the codes and published DVD-derived illustrations in our books or compiled discs containing clips from films to show in lectures. The studios didn’t seem to care, since to the best of my knowledge no teacher or scholar had ever been prosecuted for violating the DMCA.

Finally the recognition of this ludicrous state of affairs has been partially remedied. The Librarian of Congress, James Billington, himself a fine scholar in the area of Russian and Soviet studies, recommended a series of exemptions to the DMCA. The first one relates to film: “Audiovisual works included in the educational library of a college or university’s film or media studies department, when circumvention is accomplished for the purpose of making compilations of portions of those works for educational use in the classroom by media studies or film professors.” (“Circumvention” is described as “circumvention of technical measures that control access to copyrighted works.”)

This is specific to classroom situations and only applies to DVDs owned by an educational institution. What if the teacher copies clips from his/her own DVDs to use in class? (All too frequent, given the tight budgets of universities and high schools.) Nevertheless, the general implication of this exemption is that the same Fair Use principle that applied to film clips and frames duplicated from analogue copies of films (i.e., 35mm and 16mm prints) should apply even if the educator or scholar is breaking a code to do that duplication. If clips are OK, why wouldn’t single frames be?

The exemption is a small step in chipping away at the monolithic laws protecting intellectual property that the studios are determined to put in place even when it goes against their own interests. Lectures, articles, and books do not damage the studios’ ability to exploit their own films commercially (one of requirements for Fair Use to apply). Quite the contrary. Film professors show clips and still images that publicize films and possibly inspire students to rent or buy DVDs. Articles and books similarly publicize films, even though their contribution to the attention paid to any given title is minuscule.

Making an exception in the DMCA as originally passed to allow for the educational/scholarly use of digital film images would never have occurred to the studios as they lobbied for this sweeping legislation. Few movers and shakers within the industry know there is such a thing as film scholarship, much less understand what we do. Fortunately people like Billington understand. His recommended exemptions went into force November 27.

So, film educator, the next time you prepare a lecture involving clips, you don’t need to pull the curtains, lock the doors, and glance nervously over your shoulder as you copy a tracking shot from Grand Illusion and another from The Magnificent Ambersons. You are no longer a thief.