Archive for January 2007

Uncle Walt the artist

From Robert Benayoun, Le Dessin animé après Walt Disney.

The epos of Chaplin is the Paradise Lost of today. The epos of Disney is Paradise Regained.

Sergei Eisenstein

DB here:

I’m not qualified to write a comprehensive or penetrating review of Neal Gabler’s biography Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. For that you can go to Mike Barrier, one of our finest historians of US animation. Barrier’s own Disney biography will come out this spring, with apparently little overlap with Gabler’s.

I’m not qualified to write a comprehensive or penetrating review of Neal Gabler’s biography Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. For that you can go to Mike Barrier, one of our finest historians of US animation. Barrier’s own Disney biography will come out this spring, with apparently little overlap with Gabler’s.

I found Gabler’s book a thorough, somewhat cautious bio, even-handed about Disney and judicious about such controversial matters as Walt’s reputation as an anti-Semite. A lot of it reads like a notecard book, with quotes, paraphrases, and commentary dutifully snipped and pasted in, packing each paragraph. Chronology, not concept, rules. Still, I learned a lot.

Gabler’s book reminded me how much I admire Disney films. The attachment started–as for most of us–in childhood. Peter Pan (1953) was the first one I remember seeing in a theatre, but when I saw a reissue of Snow White later, parts looked so familiar that it must have impressed itself on me at an earlier time. Of course it still scared the hell out of me.

In 1973, when I was doing dissertation research in New York City, I attended a massive Disney retrospective at MoMA. As a twenty-five-year-old bearded guy among moms and kids, I felt obscurely criminal just being there, like a character in a Patricia Highsmith novel. But what I saw, in excellent prints, showed me that Disney was important on both cultural and artistic levels. So I designed a Disney unit into my first Introduction to Film course, taught here at University of Wisconsin–Madison to 300-400 souls whom fate cast my way.

I wanted to talk about film’s relation to society, and Disney was a touchstone for all my students. No matter where they came from, they knew Mickey, Donald, Snow White, Fantasia, and the rest. I showed early films, like Flowers and Trees, The Band Concert, and The Old Mill, as well as a True-Life Adventure nature doc, and the extraordinary Trip through the Disney Studio which was originally attached to The Reluctant Dragon. Students were able to see, I hope, how the ideology at work in Disney films could shape a conception of the world, of American life, and of their childhood.

Our assigned reading was Richard Schickel’s The Disney Version (1969); it’s a coruscating study, perfectly crystallizing that era’s feelings about Disney’s debasement of popular culture. At about the same time, Armand Mattelart’s Marxist critique How to Read Donald Duck was informing most film academics’ study of Disney. As Gabler indicates, intellectuals fell out of love with Disney in the 1940s. He handled labor disputes at the studio in a high-handed, paranoid way. He also seemed to personify the blandness of postwar consensus culture, and Disneyland became the theme-park equivalent of Norman Rockwell Americana. Even though hippies were turning on to re-releases of Alice in Wonderland and Fantasia, most cultural critics treated Disney pretty roughly. My friends and I goggled at Wally Wood’s 1967 Realist cartoon showing Walt’s whole gang engaging in a panoply of naughty sexual encounters.

Today the academic study of Disney is well-established, producing far too much for me to keep up with. A lot of it is cultural critique. For something funnier and even more scurrilous, see Carl Hiaasen’s Team Rodent. Despite all there is to read about Walt’s empire and its cultural consequences, I want something else as well.

Even when I was conducting my Disney Demystification Exercise, I tried to point out that these cartoons were artistically very strong. I still admire the powerfully emotional storytelling that, like that found in other fairy tales, preys so mercilessly on childhood fears. Schickel claims that after screenings of Snow White at Radio City Music Hall, the seats had to be cleaned because the Witch had scared kids into emptying their bladders.

Then too there’s the dynamism and grace of the animation, which remains unsurpassed. For Sergei Eisenstein Disney exemplified the contagious power of expressive movement on the screen. Many have disdained “Mickey-Mousing,” the close matchup between a film image and the accompanying music. But Eisenstein saw this as “synchronization of senses,” a primal, visceral unity that could move the spectator involuntarily. He sought this subconscious synchronization in his own sound films, and Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible show the strong influence of Disney.

Eisenstein was well aware of the delusional aspects of Disney, claiming that the cartoons lulled people into forgetting the harm done by capitalism. But as an artist, Disney was unique:

I’m sometimes frightened when I watch his films. Frightened because of some absolute perfection in what he does. This man seems to know not only the magic of all technical means, but also all the most secret strands of human thought, images, ideas, feelings…. He creates somewhere in the realm of the very purest and most primal depths.[1]

Disney’s art seems magical, but if it’s not a miracle, we ought to be able to study it systematically. How?

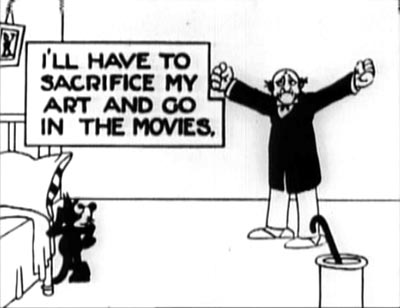

Felix in Hollywood (1923)

Felix in Hollywood (1923)

For the Jung at heart

Gabler’s is a sturdy, readable volume teeming with fascinating background material. As an EEG of the ups and downs of the studio, it’s extremely valuable. Gabler also aims to give a portrait of Disney the visionary, a man of boundless Protestant energy who sought to take animated film to ever higher levels. I think the portrait is disappointing, though, in its reliance on conventional psychobiography and Zeitgeist explanations.

Disney, Gabler claims, was dominated by a psychological drive to create a world wholly of his own. He was a control freak. “It had always been about control, about crafting a better reality than the one outside the studio, and about demonstrating that one had the capacity to do so. That was what Walt Disney provided to America–not escape, as so many analysts would surmise, but control and the vicarious empowerment that accompanied it.”

Commentators have long noted that Disney expanded the films’ fantasy world in his theme park. Just as films idealized reality, “so would Disneyland, the creation of a wounded man who expunged what he saw as the darker passages of his past by devising a better world of his imagination, though one that was obviously colored by the images of Hollywood.”

One has to wonder whether this characterization is particular to Uncle Walt. Lots of artists, from architects and topiary gardeners to designers of world’s fairs, have sought to create imaginary worlds over which they rule. Balzac, Faulkner, Lewis Carroll, and J. R. R. Tolkien conjured up imaginary realms populated by dozens of their own creatures. Graphic artist Ho Che Anderson writes:

For the control freak, there are few places better than comics. . . . Pick up a pen and piece of paper and you too can effectively play God. I suspect this love of God-play is the blood that keeps the hearts of many a cartoonist beating.[2]

Moreover, is the desire to build a parallel world necessarily a sign of a wounded past, or dark imaginings? Maybe it’s just one awesome creative challenge for ambitious artists. Granted, Disney took this impulse in a particular direction, toward a vision of life combining technical progress (the multiplane camera, Tomorrowland) with idealized notions of small-town community. But then we have to explain those idiosyncratic factors too.

Gabler goes the psychological route, but we could balance this account with cultural factors in Disney’s immediate milieu. There was the rise of the Technocracy movement. There was Hollywood’s belief that filmmaking would progress through new technologies. There was growing evidence during and after World War II that America’s might would be built on new machines. (One of the most hair-raising movies I saw at the 1973 MoMA Disney fest was Victory through Air Power, an educational short arguing for investment in airborne warfare.) Disney was, along many dimensions, a techie impresario, the Steve Jobs of his day, complete with his unique reality-distortion field.

The other big-picture explanation Gabler offers is a Zeitgeist model. Disney represents the American imagination. By tapping into Jungian archetypes, his 1930s films could both “capture and then soothe the national malaise.” More generally: “In both Disney’s imagination and the American imagination, one could assert one’s will on the world . . . . Indeed, in a typically American formulation, nothing but goodness and will mattered.” Disney’s desire to retreat into a controlled world echoes his country’s self-absorped conception of itself.

Despite these claims, Gabler doesn’t dwell much on the ways the studio seized what he calls “the American psyche,” perhaps because he senses that such explanations tend to be uninformative. One can grab almost any cluster of traits, find them in American popular art, and assert them as quintessentially American. This is how mainstream journalists make current Hollywood releases worth writing about: treating them not as artworks with distinctive appeals and a place in traditions and histories, but as reflections of whatever immediate social trends the writer chooses to pick out.

I won’t extend my criticism of Zeitgeist explanations here; it’s developed in the first essay in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema. I’ll just say that I think we need more precise explanations than we get from easy juxtapositions of this or that film and some collective mood, sentiment, fantasy, or anxiety that we postulate as existing out there. Is there an American psyche? I’m not convinced.

An alternative to psychological speculation and Zeitgeist thinking is to look for more immediate causal connections. For example, Gabler traces how, around 1932, Disney began a new division of labor among his staff. He created a fairly strict set of specialties (story, gags, continuity sketches) and a chain of command in which head animators would become directors, overseeing particular projects. What’s the explanation of this change of policy? For Gabler, the new rationalization reflects not only the need to manage a bigger staff but also Walt’s effort in “reinventing and perfecting the system under which animations were produced.”

Gabler doesn’t mention that reorganizing the division of labor was going on throughout Hollywood at the same time. Most major studios were moving from a central producer system (this parallels the previous Disney lineup, with Walt at the top) to what Janet Staiger has called the producer-unit system, in which each man was charged with several productions.[3] Mentioning this doesn’t take away from Disney’s resourcefulness, but it does indicate that models for organizing his company were emerging right under his nose.

Similar issues could be examined by looking at Disney’s place in the overall ecology of Hollywood, as the premiere supplier of short subjects. His firm, Douglas Gomery argues, kept RKO afloat for many years. Gomery’s Hollywood Studio System: A History gives a cogent account of Disney’s role in the industry, and he goes somewhat beyond Gabler in tracing the studio’s emergence as in the 1950s as the prototype of modern conglomerate filmmaking.

Life in the cel

For Gabler, what made Walt reorganize production, and indeed what made him do nearly everything, was his obsessive pursuit of “quality” animation. But this quality itself remains fairly mysterious.

For Gabler, what made Walt reorganize production, and indeed what made him do nearly everything, was his obsessive pursuit of “quality” animation. But this quality itself remains fairly mysterious.

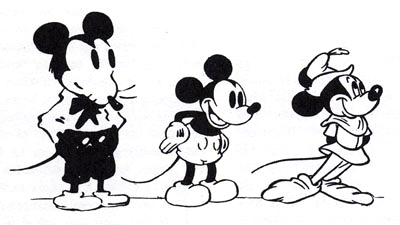

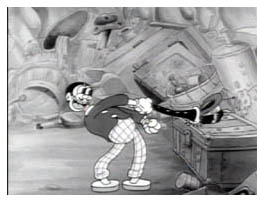

Gabler indicates that Disney moved away from the “rubber-hose” style of most cartoons, with their balloon heads, swollen paunches, and elastic arms and legs. (Even the clarinet goes limp in Harman-Ising’s A Great Big Bunch of You, from 1932, shown here.) Floppy limbs were fairly easy to animate. Gabler briskly summarizes Team Disney’s well-known innovations in naturalism, such as the studio’s emphasis on anatomy and life drawing, the breakdown of gestures, complex perspectives, and the rotoscoping of human figures.

Yet Gabler, a former movie critic for television, oddly doesn’t engage with the result of the technical innovations. He summarizes how journalists, critics, and academics have interpreted the movies’ cultural impact, but what he thinks about them as movies, rather than social or psychological symptoms, is almost completely suppressed. Does he admire Snow White or Dumbo or Pinocchio? Does he hate them? Has he studied them in preparation for the book? You will find more sensitive appreciation and critique in Leonard Maltin’s The Disney Films than in all of Gabler’s doorstop tome.

Gabler implicitly acknowledges the technical achievements of Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi, but after that he merely chronicles release after release with deadpan indifference. For example, he offers us nothing on the brilliant character animation of Song of the South (1946)–a film no longer in circulation because of its racial stereotyping.

Gabler follows tradition in suggesting that the UPA studio movies challenged Disney’s hyperrealism, but Disney was already moving toward something quite stylized. Gabler doesn’t observe the zesty play with color and line of Melody Time‘s “Blame It on the Samba” episode (1948). Eisenstein would have been pleased to see that the handling of Donald and Jose literalizes the metaphor feeling blue.

Working with lower budgets in the 1940s, the animators let their imaginations run wild. What a pleasure it must have been for Ward Kimball to come up with the funhouse nuttiness of the Serape song in The Three Caballeros (1945).

Kimball must have been quite a character; his parody book Art Afterpieces doesn’t spare the studio’s creatures. More generally, when Disney animators turned to illustrating pop music, they didn’t abandon the wilder sides of Fantasia.

There would be several fruitful ways to study the Art of Uncle Walt. One would require what I call rhapsodic criticism, writing that tries to evoke the movie’s look and feel through energetic, sensuous description. (This is, I think, what Susan Sontag meant in calling for “an erotics of art.”) Here is Don Crafton on the Felix the Cat cartoons:

Perhaps the most appealing aspect of Felix was his use of expressive body parts–a tail that forms gratuitous curlicues when he walks, or ears that click together like scissors. . . . He can mold himself into a mantel clock and have his nose mistakenly wound up; his tail can be an umbrella, a sword, or a clarinet, or Chaplin’s cane. He can use the tail as a bow to play a tune on his whiskers, then take one of the rising notes and use it for a doorkey. His skin is detachable. In Felix Trifles with Time (1925), a tailor flays him, then outfits a client with his pelt. When the man goes swimming, “naked” Felix retrieves his hide from the beach. [4]

In brief compass Crafton brings Felix alive for us. You don’t have to love Disney to write this way about his films; you do need a good eye, some pluck and gusto, plus a gift for language. Nothing like this is to be found in Gabler’s book.

Another way to get closer to Disney’s art is to just look at things more analytically. How does Disney create that expressive movement that Eisenstein admired? Partly, it seems, through having his figures move all over, and at the same instant. Reacting to a line of dialogue, a character can twist his waist, arch his back, swivel his shoulders, lift his head, arch his eyebrows, and raise a forefinger–all in a second or two. Two successive frames from Melody Time show Johnny Appleseed’s guardian angel in action, working his legs, arms, shoulders, jaw, and eyeballs simultaneously.

This is far from the minimal animation to which we became accustomed in the TV era. Treating gesture as a taut, rolling movement helps give Disney characters their unique volume and springiness, so different from the flabby postures of the rubber-hose style.

Or consider pacing, at which the Disney cartoons excel. Most studio animation of the period, constrained by smaller budgets than Disney had, speeded up production by filming each frame twice. That way only 12 cel drawings were needed for the 24 frames that consumed a second of film. One way Disney achieved expressive action, and the high quality to which Gabler refers, was to devote single frames–and cels–to details of particular movements. This choice, though expensive, allowed for exact adjustments in rhythm.

Sometimes there’s more than one movement per frame. You can occasionally find this strategy at work in other studios’ cartoons too, as Kristin has explained in an essay she mentions elsewhere in our blog. But Disney’s animators certainly used the technique with great panache. When Johnny, balancing on a branch, is caught in a rain of apples, he sweeps them up with lighting speed–a deft swirl made possible by multiplying character poses on each cel. If that means giving Johnny many arms and even detaching his hands, so be it.

Johnny’s arms and hands proliferate more quickly and widely as he scoops up the apples, but their number is reduced as he gathers them in to his chest, so the rhythm accelerates and decelerates. Through trial and error Disney’s animators learned that rather strange single images will look exactly right on the screen; these men were practical perceptual psychologists.

There are so many aspects of Disney’s art that need attention: the skill with line and contour; the sort of soft caricature that some consider cutesy but has enormous bounce and vibrancy; the ingenious use of color; and of course, Eisenstein’s “synchronization of senses” between image and music. There’s also Disney’s appropriation of developing live-action techniques, as in the proto-Wellesian crane shot in Pinocchio

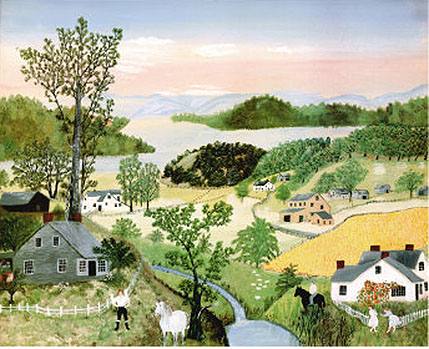

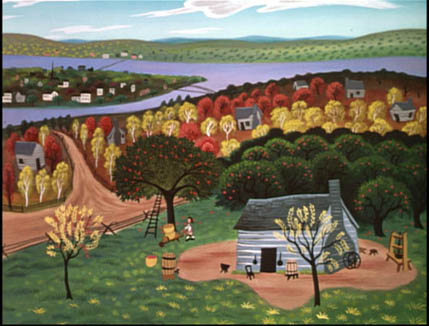

One could also study the studio’s borrowing of high-art motifs and styles. Instead of dismissing the 1940s and early 1950s Disneys as greeting-card kitsch, we can note that they evidently borrowed from the likes of WPA landscape art, American regionalist painting, and the naive-art look of Grandma Moses. (Her painting A Beautiful World, 1948 resembles Disney’s Johnny Appleseed of the same year.)

I’m a duffer in animation matters, so I’ve merely indicated some areas that intrigue me. The key source on the studio’s craft practice remains the gorgeous book The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation (1981, rev. 1995), by two of the great Nine Old Men, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnson. And I expect lots of discoveries in years to come from experts like Barrier, Maureen Furness, Paul Welles, Norman M. Klein, and many others. Since Gabler draws heavily on the research of others, often without naming names, he might have borrowed a bit more from scholars of animation aesthetics.

In fact, you could argue that without the artistic imagination displayed by Disney and his brilliant staff, these films couldn’t have captivated the American imagination. Whatever that is.

[1] Eisenstein on Disney, ed. Jay Leyda, trans. Alan Upchurch (Calcutta: Seagull, 1986), 2.

[2] “Career Tips for Control Freaks,” in The Education of a Comics Artist, ed. Michael Dooley and Steven Heller (New York: Allworth, 2005), 124-125.

[3] Janet Staiger, “The Producer-Unit System: Management by Specialization after 1931, in David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 320.

[4] Donald Crafton, Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898-1928 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993; orig. 1982), 327, 328.

Snakes, no, Borat, yes: Not all Internet publicity is the same

Kristin here–

This past summer I had my first experience of being quoted as a pundit in a major newspaper. The Los Angeles Times was planning a story on the internet buzz around Snakes on a Plane and more specifically around the fact that some of that buzz had actually influenced New Line to change the film.

In late July I had completed the final revision and updating on The Frodo Franchise. Two chapters cover the official and unofficial internet publicity for The Lord of the Rings. The last thing I had added to those chapters was a reference to the Snakes internet phenomenon—which was still ongoing, of course, since the film was not released until August 18. The connection is closer than it may appear, since New Line distributed both films.

Dawn Chmielewski, of the LA Times, got wind of my work on fans and the internet. She called me, and we had a pleasant 40-minute conversation. The result was one pretty uncontroversial statement from me near the end of the story, describing how studios have a mixed attitude toward fan sites on the internet: “It is a phenomenon where the studios are having to keep a delicate balance between, on the one hand, wanting to use this enormous potential for publicity, and on the other hand have to control over copyrighted materials and over spoilers.”

This story was part of the huge amount of attention paid to the Snakes phenomenon, with Brian Finkelstein, webmaster of the main fan site, Snakes on a Blog, widely quoted about how New Line had cooperated with him and even invited him to LA for the premiere. One of the main points of interest to the media was that New Line had added a line of dialogue that had originated on a fan site for Samuel L. Jackson’s character. The studio also added some sex and gore, moving the film’s rating from PG-13 to R.

Fans’ influencing films was not entirely new by this point. After The Fellowship of the Ring came out in 2001, two fans elevated a non-speaking elf extra from the Council of Elrond to fame by dubbing him “Figwit” and starting a website devoted to him. As a salute to the fans, the filmmakers brought the extra back and gave him one line to say in The Return of the King, where he is credited as an “Elf escort.” That phenomenon, however, didn’t get much notice beyond fan circles. The Snakes revisions got far more attention.

Much was made of the fact that industry officials were eager to see whether wide internet buzz—especially when covered by mainstream news media—would translate into boffo box-office figures. As we all know by now, Snakes was a deemed a failure. New Line said that its opening gross was typical for a low-budget genre film. Snakes cost a reported $33 million. Ultimately it took $34 million in the domestic market and a total of just under $60 million internationally. I suspect that New Line spent a great deal more on advertising that it ordinarily would have, hoping in vain to expand the enthusiasm. The film’s box office takings would certainly not bring in a profit, but doubtless New Line hopes for better things on DVD. That DVD was released on January 2, so no sales figures are available yet, but the widescreen edition is doing reasonably well at #19 on Amazon.

The film’s disappointing ticket sales led to questions. Why would fans spend so much time on the internet and generate such hype and then not go to the film? After all, fans created parody posters, music videos, comic strips, and photos on their sites, as well as designing T-shirts and other mock-licensed products. (The DVD supplement “Snakes on a Blog” presents a generous sampling of such homages; see also Snakes on Stuff.com.) And if that much free hype—even aided and abetted by the studio—didn’t translate into ticket sales, was the internet all that useful for publicizing films?

The film’s disappointing ticket sales led to questions. Why would fans spend so much time on the internet and generate such hype and then not go to the film? After all, fans created parody posters, music videos, comic strips, and photos on their sites, as well as designing T-shirts and other mock-licensed products. (The DVD supplement “Snakes on a Blog” presents a generous sampling of such homages; see also Snakes on Stuff.com.) And if that much free hype—even aided and abetted by the studio—didn’t translate into ticket sales, was the internet all that useful for publicizing films?

Of course fan sites had already proven their worth for New Line’s own Austin Powers: Man of Mystery and Lord of the Rings. Other films had benefited from free fan labor and enthusiasm. Famously The Blair Witch Project became a massive hit primarily because of the internet. But anytime a hitherto dependable formula results in even a single failure, the studio publicity departments go into a tizzy of doubt. It’s true of genres, stars, and just about any other factor you can name. Snakes fails, so maybe the internet isn’t that powerful a publicity force.

Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan came along to confuse things even further. It, too, had a huge fan presence on the internet. In this case, the main activity was the posting of clips on YouTube. Well before the film was released on November 3, deleted footage and some scenes from the film were showing up. There were about 2000 by then, and as of yesterday a search for “Borat” on YouTube yielded 6,293 items.

It came to be a joke on the internet: “What is the difference between Google and Borat? The latter knows how to make money from YouTube.” (“Borat” was recently reported to be one of the top search terms on Google in 2006.) Webmasters and chat-room denizens who were already fans of Sacha Baron Cohen from Da Ali G Show, where the Borat character originated, promoted the film. The internet buzz probably led to more coverage of the film in mainstream infotainment outlets than would have otherwise occurred.

Borat’s reported budget was $18 million. To date, it has grossed $126 million domestically and a total of $241 million worldwide.

The timing of the two events triggered much press coverage and show-business hand-wringing. What did it all mean? Is the fan-based sector of the internet good for films or not?

This isn’t some idle question as far as the industry is concerned. Twentieth Century Fox wisely encouraged all the Borat uploaders at YouTube. Far from threatening to sue over copyright, they leaked footage. Then, however, shortly before the film’s release, audience research (that highly dubious tool in which studios put such faith) revealed that many members of the public had never heard of Borat. What to do? At the last minute Fox cut back the number of theaters in which the film would be shown. Did anyone else in the world think that was a good idea?

Back on November 11, with Borat freshly successful and speculation about internet coverage rife, I promised to explore how the two films differed when it came to internet hype and success. That would be possible to do without seeing either film. I saw both, though. Like many others, I watched Borat in a theater and Snakes on DVD.

Others have offered reasons for the difference. On NPR, Kim Masters made some plausible observations. Snakes, she points out, “was a film with a very broad concept—Samuel L. Jackson battles snakes on a plane. The buzz took off on thousands of Web sites as the film became the butt of many jokes. The problem is that the movie wasn’t really meant to be that funny. Borat, on the other hand, is meant to be funny.” True enough. In fact, Snakes has a weird mixture of tones, starting off with a highly non-humorous scene of a gangster killing a man with a baseball bat. It goes on to interject funny moments in the midst of grim ones in a seemingly random way.

Moreover, Masters claims, the buzz for Snakes “took off too fast” and in the wrong places. The sites making all the jokes and parodies weren’t the same ones that horror fans frequent, and the humor may in fact have created a negative reaction among what would ordinarily have been the film’s target audience. Borat had no such problem. Fans of comedy and especially of Cohen spread the word to likeminded fans through what is termed viral marketing in the publicity business.

All true, and yet, having studied Lord of the Rings fan sites for a long time, I think there was another crucial factor that never occurred to the anxious studios. That factor was what the fans were doing with the films on their websites, in chat rooms, and on YouTube.

Many popular films, especially in genres like fantasy, science fiction, action, and horror, generate fanfiction, fanart, spoofs, and other creative responses. Snakes on a Plane offered the inspiration for all sorts of clever writing and drawing and videomaking through its title alone. As was pointed out over and over, from that title and the casting of Jackson, everyone knew what the film would be like. It could be parodied without even being seen. Indeed, I suspect that after months of posting and mutually enjoying hundreds of amusing riffs on “Snakes on a Plane,” many fans realized that they could never have as much fun watching the film as they had playing around with its title and concept. It had never been the movie itself they were really interested in.

Borat’s full, unwieldy title was also an attention-getter, but no one could possibly predict much about the film from it, let alone parody it. Here the focus was primarily on how funny Cohen was as Borat and how funny the film was going to be. What circulated were samples that seemed to prove exactly that. People would go to this film and have more fun than they could possibly make for themselves by messing around on the internet with its title. The words “snakes on a plane” could inspire just about anybody with a creative bone in their body, but only Cohen could do Borat.

Print and broadcast media spread the same message. For Snakes, they had zeroed in on the internet coverage and stuck with that. End message: there is a lot of fan attention being paid to a rather silly-sounding film. For Borat, they had Cohen appear as an interviewee.

Cohen brilliantly manipulated the infotainment outlets, especially the chat shows, by appearing in character as Borat. As the film’s release approached, Cohen was a hot property, a ratings booster. Talk-show hosts and soft-news reporters presumably couldn’t alienate him by insisting that he speak as himself. Maybe they didn’t want to. As a result, three things happened. First, the endlessly talkative Borat dominated each interview. On The Daily Show, the ordinarily in-charge Jon Stewart was totally unable to control the situation and frequently cracked up, once badly enough that he had to turn his back on the audience momentarily.

The second result was that each appearance by “Borat,” supposedly there to talk about the film, ended up being a hilarious performance by Cohen, ad-libbing on everything around him—the chairs, the coffee mugs, the cameras, the audience. Spectators ended up with one impression about the film: it was about this incredibly funny guy doing incredibly funny things.

Third, there could be no discussion of the less savory aspects of Borat, the ones that mostly surfaced after the film was already a hit. These included allegations that people had been manipulated by false claims into signing consent forms and “performing” in the film. One has to suspect that when Cohen was explaining his project to them, he may have appeared as his own rational self and not in the wild-and-crazy persona of Borat. The stylistics of the film itself betray many points at which encounters with real people could have been manipulated. Who knows what the crowds at the rodeo where Borat butchers the national anthem were actually reacting to? None of their responses is ever visible in the shots of Borat. How many non-bigoted interviews were thrown out for every bigoted one that could be used?

The point is, though, that the interviews were like the internet clips, furnishing more evidence of how entertaining the film would be. Borat could provide a sort of creativity that was all his own, and fans could never imagine it ahead of seeing the film or create a more fun version of it themselves. Many, many of the people who posted or read stuff about Borat on the internet went to the film.

Ultimately the studios have yet to emerge from their early love-hate relationship with fan-generated publicity on the internet. They dread the early posting of bad reviews and crave good ones, naturally. But they still seem to believe that most other online publicity means the same thing: eyeballs on monitors should equal bottoms in theater seats. Publicists have not yet grasped that fans don’t go to the web just to talk about films and learn about films. They do things with films, and different films inspire different sorts of activities. Those different activities may or may not mean that the fan ultimately wants to see the film itself.

In most cases they probably do end up seeing the film. Snakes on a Plane is most likely an aberration, as Blair Witch was. But Snakes does prove one other thing. Fawning attention paid to the webmasters and bloggers who launch these unofficial campaigns is no guarantee of success. The “Snakes on a Blog” supplement displays some interesting aspects of New Line’s wooing of the main fans involved in the online hype. The documentary seems to have been made at just about the time Snakes was released. It ends with the bloggers, by invitation, on the red carpet at the Chinese Theater for the film’s premiere and later at the bloggers’ party put on by New Line at a bar. The whole tone is very enthusiastic about the internet’s impact on the film’s success; there is no sense that the film will disappoint and raise doubts about the value of fan publicity. There is also the implicit suggestion that fans starting future film-related blogs might get similar encouragement and hospitality from studios.

Clearly no amount of studio cooperation and attention to fans’ interests will make a film succeed if the right blend of ingredients isn’t there. Nevertheless, fans’ enthusiasm and willingness to spend great amounts of time, effort, and even their own money to create what amounts to free online publicity for films is of incalculable value to the studios. Yet for the most part those studios are still making only grudging, limited use of this amazing resource. The resentment they garner from fans as a result may be squandering part of that resource’s potential.

Gradually, though, the studios are giving up their policy of stifling the fans by making vague threats about copyright and trademark violations. If they go further and actually learn how fans use all the amazing access the internet has given them, maybe movie executives can relax and recognize the obvious answer to the current debate: Yes, fans on the internet are good for the movie business.

My Danish December

Easy Skanking (aka Fidibus).

DB here:

I’d intended to post this at the end of the year, but I fell behind. So in place of the New Year’s entry Kristin and I had hoped to write, we’ll just say: Best wishes for 2007!

And now the blog….

I haven’t bothered to draw up a list of best films of 2006, for lots of reasons. Some acute objections to the very idea of best-films lists are aptly summarized by Andy Horbal, and I find them convincing. But there have been practical concerns too.

My December movie-watching was dominated by 2004-2006 Danish films, in preparation for an essay. I think I couldn’t have spent my time better. Instead of being disappointed with critics’ official hits from the US, I was repeatedly excited by ingenious, moving, and enjoyable films….most of which I wouldn’t have known about otherwise.

First, some background.

Historically, it seems, the three greatest national cinemas are those of the US, Japan, and France. Their pervasive influence and their accomplishments in film art, film industry, and film culture make them consistently important in every era, from 1895 to the present.

But a lot of other national cinemas are important too, and I confess a fondness for those less salient ones, what Mette Hjort calls, without disparagement, cinemas of small nations. It’s partly because my academic life has been bound up with not only the Big 3 but a littler 3: Belgium, Hong Kong, and Denmark.

Denmark was the first foreign country I ever visited; I went there in 1970, just before starting graduate school, to do research on Carl Dreyer. I was received so hospitably by Ib Monty, Karen Jones, Marguerite Engberg, and others at the Danish Film Archive, that I came to believe that I could continue to do academic work on cinema.

Over the last 36 years, I’ve felt a kinship with Danish film culture. It has admirable directors like Dreyer and Benjamin Christensen, of course, but also without a lot of fuss the Danes keenly support artistic cinema in a commercial context. I’ve come to respect their open, unpretentious approach to filmmaking and film viewing. I’ve also made many strong friendships with Danish archivists and professors.

The Danish Film Institute not only helps fund most of the 15-20 titles theatrically released every year. It also proselytizes very actively for those films, helping them get festival slots and theatrical releases overseas.(Several Danish items will be screened at Sundance this month.)

The DFI’s job has gotten easier since the arrival of Dogme 95, which galvanized filmmakers around the world and made Danish film the flagship of Scandinavian cinema. Here is Norwegian director Aksel Hennie: “The effect of Dogme on my generation has been immense. More than anything else, it is the Dogme attitude, the ‘anybody can make movies’ idea. As a first time director with no formal training from a small European country, that was very inspiring.”

In 2002, Vicki Synnott of the DFI asked me to write an essay about post-Dogme Danish films for their publication Film, which appears in English in spring, summer, and fall. I reviewed about thirty titles, only a few of which I’d already seen. The result, “A Strong Sense of Narrative Desire,” can be downloaded here.

In 2005, Vicki asked me for a more up-to-date piece, and she sent me another passel of films to watch. Hence my December movie marathon, and the essay, which I’ve just submitted. After polishing, it will be published in print and will be available online.

I thought that a good way to start the new year would be to talk about the most intriguing and enjoyable films I saw. Most are little-known outside the festival circuit, and very few are as yet available on DVD. But all are well worth your time. So call it my Best Danish Films I Saw at the End of 2006 list.

Thrillers

The King’s Game (2005) offers journalistic-political intrigue in the vein of All the President’s Men. Efficiently directed and plotted, with some earned surprises, it also features those doyens of Danish acting, Anders W. Berthelsen (Mifune) and Søren Pilmark.

Murk (2005) shows off again the estimable talents of screenwriter (sometime director) Anders Thomas Jensen. A little implausible in the third act, but excellent suspense and fine performances from the ubiquitous Nicolas Bro and Nicolaj Lie Kaas.

Flies on the Wall (2005): Another political thriller, this one for the digital age. A documentary filmmaker (Trine Dyrholm, another fixture of modern Danish film) is commissioned to make a film promoting a political party. She finds a scandal instead. Director Åke Sandgren creates a dizzying montage of footage from the hidden cameras she plants among the offices and in her motel. At a certain point, though, we realize that some of the footage comes from cameras spying on her.

I plan to write more about this rather dazzling movie in another essay.

Ambulance (2005): The idea is worthy of Larry Cohen. A botched bank robbery forces the thieves to hijack an ambulance to make their getaway…with an attendant and a critically ill patient still inside. Unfolding in more or less real duration, the film barrels along breathlessly but still pauses for moments of character revelation and disputes about moral choices.

Pusher III (2005): Even grimmer than the first two installments, but completely gripping in its portrayal of a man whom we should consider utterly degenerate. Nicolas Winding Refn makes the milieu of The Departed look like a ten-year-old’s birthday party. There’s also an intriguing documentary, Gambler (2006) about the financial pressures that forced Refn to make the two final Pusher films.

Comedies

Clash of Egos (2006): A high-concept satire of the film industry by, once more, Anders Thomas Jensen. Through a legal settlement, working-class Tonny gets a chance to oversee a pretentious movie director’s next project.

Lotto (2006): Danish comedies often have a moral issue at their center, one that’s usually more subtly developed than the morality of Hollywood films. Here the situation is: If you and your workmates pooled to buy a lottery ticket and it won….should you tell them? Another fine Pilmark performance, this time in mild-mannered mode.

Easy Skanking (2006; illustration up top). Originally titled Fidibus, which refers to somebody serving as a gofer for a drug dealer. This is a lively venture into Pulp Fiction and Trainspotting territory, but with a sweeter tone and a happy ending. Rudy Køhnke, Denmark’s answer to the young George Clooney, works for the fearsome pusher Paten, but falls in love with Paten’s mistress. You can check out trailers here and here.

Adam’s Apples (2004): A little older, but I had to include it just because it’s one of my favorite films of recent years. Written and directed by Jensen, it tells of a daffily upbeat priest’s efforts to reform convicts, including the skinhead Adam of the title. Tough and warm-hearted at the same time. Mads Mikkelsen, now famous thanks to Casino Royale, plays the priest, with Ulrich Thomsen of Flickering Lights as the edgy miscreant.

Dramas/ Melodramas

Susanne Bier’s After the Wedding (script by Jensen) has already received plenty of praise. It’s another poised, sensitive study of love and family in the vein of Open Hearts (2002), but with a more socially engaged dimension. The protagonist, played by Mikkelsen, has transformed himself from a dissolute vagabond into a worker in an orphanage in India, but his past returns to threaten his redemption. If American critics had seen this film, or if it had been distributed in the US, it would have appeared on many ten-best lists.

1:1: Annette K. Olesen’s tale of the racial tensions surrounding an attack on a teenager. As often in Danish films, psychological drama is balanced by a consideration of social context. The opening credits play out against blueprints and documentary footage detailing the construction of the housing development that forms the center of the action.

Prague (2006): Christoffer, a hard-working businessman, comes to Prague to claim the body of his father, whom he never really knew. His stay leads to a crisis in his past, as he learns his father’s secrets, and one in his present, as he and his wife face the breakdown of their marriage. A severe, engaging film with some of the tang of mid-period Antonioni, starring Mikkelson and Stine Stengade.

A Soap (2006): Pernille Fischer Christensen’s debut has already racked up festival prizes. The action unfolds wholly in an apartment building, where Charlotte (Trine Dyrholm, another fixture of modern Danish film) and the transvestite Veronica (David Dencik) strike up a relationship. Almodovarish, but more subdued (Danes aren’t Spaniards, after all).

How We Get Rid of the Others (2007): In the near future, Copenhagen creates laws that eliminate all citizens who take more from society than they give. A dark, 1984ish vision that satirizes how communitarian social policies can turn tyrannical.

Unclassifiable

The Boss of It All (2006): I’ve already discussed this here, and have recently added a couple of updates. Surely one of the most artistically daring films of the year. Funny too.

Day and Night

Bang Bang Orangutang (2005): Simon Staho is virtually unknown in the US, but his previous feature Day and Night (2004) takes minimalist cinema in a new direction. Perhaps inspired by Kiarostami’s Ten (2002), Staho pushes the camera/car conceit toward more classical staging and shooting. His followup, Bang Bang, opens up a bit more–now the camera occasionally leaves the car–but Staho goes on to create new formal constraints. The story? A heartless businessman sinks to the bottom of society and out of touch with reality.

Offscreen (2006): After the Neoromanticism of Reconstruction (2003) and Allegro (2005), Boe, in collaboration with Nicolas Bro, creates a more-or-less fictitious diary film. Bro becomes obsessed with recording his life on video, and that leads him to horrific violence. An absorbing exercise in first-person cinema, with viewpoints multiplied (as in Flies on the Wall) thanks to mini-cams.

I hope to write more on these formally adventurous films. (I did: here and here, both for the DFI.)

Watching these films over several weeks, I was even more convinced that today’s cinema encompasses far more than even the most pluralistic ten-best lists can allow. Lists are helpful for some purposes, but our time is better spent seeking out unusual movies, listed or unlisted.