Archive for March 2007

Trims and outtakes

Some jottings from DB:

Continuity Boy meets Badgers

Tim Smith, who studies how we perceive film, recently visited our department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His talk was splendid.

Tim Smith, who studies how we perceive film, recently visited our department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His talk was splendid.

Tim studies the ways we scan shots and shift our attention across cuts. His talk was illustrated with film sequences showing little yellow dots swarming around the frame; these indicate the points in the image where his subjects’ glances landed. Tim shows pretty conclusively that there’s a consensus about where viewers look during a shot (faces, movement, the center of the frame) and that classical continuity cuts can push our attention to and fro with remarkable facility. One of the most surprising findings was that viewers are often starting to shift their attention to a new frame area just before the cut comes. Why? Tim has some intriguing suggestions.

Tim also showed some remarkable effects of what I’ve called “intensified continuity,” the fast-cut close-ups that characterize so much current cinema. Because these passages leave no time for visual exploration, viewers seem to revert to a cursory test for the shot’s basic point, usually at the center of the frame. Tim’s examples from Requiem for a Dream were fascinating, showing how real viewers are playing catchup in very fast-cut sequences.

This is rich and promising research, showing once more that Leonardo da Vinci, Eisenstein, and a few others were right to think that many creative choices in the arts can be studied with the tools of science. It also shows that filmmakers, like other artists, are seat-of-the-pants psychologists, achieving complex effects through decisions that “feel right” and that they have no need to explain theoretically. That’s our job.

For Tim’s narrative of his visit, and a lot more about his research program, go here. For something not quite completely different, about eye-tracking, print ads, and crotches, go here.

Six more from RKO

The enterprising folks at Turner Classic Movies have discovered six RKO films that have been missing for many years. It’s a harvest of 1930s titles, promising some intriguing situations (e. g., Ginger Rogers as a telemarketer) and carrying the names of directors like William Wellman, John Cromwell, and Garson Kanin.

A Man to Remember (1938; at the top of this page), Kanin’s first film, is the only one of the batch I’ve seen so far. One of the New York Times‘ ten best films of 1938, it went virtually unseen until a print surfaced at the Netherlands Filmmuseum in 2000. A Man to Remember is a portrait of a small-town doctor who tends to the poor and lets others, chiefly a cadre of corrupt businessmen, take credit for his good works.

It could all be mawkish, but Edward Ellis plays the doctor as a testy guy who levels with his patients and wins the town’s respect through quiet cussedness. The performance echoes Ellis’ crabby but likable inventor in The Thin Man (1934). Dalton Trumbo’s script has an intriguing flashback structure, less bold than in The Power and the Glory (1933) but still ambitious for a B project.

The six RKO discoveries are screening on April 4th as an ensemble, then they’re scattered through the rest of the month. All should be worth checking out. Once more TCM proves itself the film-lover’s channel of first choice.

Bambi or kitty?

Two recent books support the claim that New Hollywood, or New New Hollywood, is at bottom in debt to old Hollywood. (The full case is presented in The Way Hollywood Tells It and Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood.)

David Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon) is as pungent and eccentric as you’d expect, but also deeply traditional in its storytelling advice. A movie’s characters must have goals, and over the course of three acts they achieve them, or definitively don’t. The Lady Eve is Mamet’s model of this construction. Furthermore, three questions structure every scene: Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don’t get it? Why now? In wide-ranging essays, Mamet pays tribute to the craftsmanship of below-the-line talent and celebrates movies as various as The Diary of Anne Frank and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (whose protagonist is remarkable for “his personification of enigma”).

David Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon) is as pungent and eccentric as you’d expect, but also deeply traditional in its storytelling advice. A movie’s characters must have goals, and over the course of three acts they achieve them, or definitively don’t. The Lady Eve is Mamet’s model of this construction. Furthermore, three questions structure every scene: Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don’t get it? Why now? In wide-ranging essays, Mamet pays tribute to the craftsmanship of below-the-line talent and celebrates movies as various as The Diary of Anne Frank and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (whose protagonist is remarkable for “his personification of enigma”).

Mamet adds a fair amount on editing, supplementing the remarks in his Pudovkin-flavored On Directing Film. For instance: “At the end of the take, in a close-up or one-shot, have the speaker look left, right, up, and down. Why? Because you might just find you can get out of the scene if you can have the speaker throw the focus. To what? To an actor or insert to be shot later, or to be found in (stolen from) another scene. It’s free. Shoot it, ’cause you just might need it.”

Mamet bemoans the script reader, whose motto must be Conform or Die. By contrast, Blake Snyder makes conformity seem fun and–well, if not easy, at least attainable. His Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need (Michael Wiese Productions) bulges with formulas, recipes, and gimmicks.

Like Kristin and me, Snyder treats the Second Act as really two sections, broken by a midpoint. But for him three acts are just the beginning. He demands that there be an Opening Image (on script p. 1), Theme Stated (p. 5), Catalyst (p. 12) and on and on until we get the Finale (pp. 85-110) and the Final Image (p. 110). This is the most strictly laid-out cadence I’ve seen; it would be fun to see if actual scripts adhere to it. In addition, you get catchy tips like Save the Cat! (show the protagonist doing something likable early on) and the Pope in the Pool (burying exposition). Snyder includes a list of the most common screenplay errors. An enjoyable read with some hints about construction I hadn’t encountered before.

Like Kristin and me, Snyder treats the Second Act as really two sections, broken by a midpoint. But for him three acts are just the beginning. He demands that there be an Opening Image (on script p. 1), Theme Stated (p. 5), Catalyst (p. 12) and on and on until we get the Finale (pp. 85-110) and the Final Image (p. 110). This is the most strictly laid-out cadence I’ve seen; it would be fun to see if actual scripts adhere to it. In addition, you get catchy tips like Save the Cat! (show the protagonist doing something likable early on) and the Pope in the Pool (burying exposition). Snyder includes a list of the most common screenplay errors. An enjoyable read with some hints about construction I hadn’t encountered before.

Speaking of screenplays….

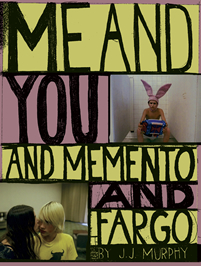

J. J. Murphy is an old friend (we went to grad school with him in 1971) and colleague (he teaches in our department). Renowned as an experimental filmmaker, he has turned his attention to American indie cinema. His new book Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work offers an in-depth analysis of several recent films. J. J. shows how they obey mainstream conventions of construction while still innovating in other ways. I especially like his discussions of Hartley’s Trust, Korine’s Gummo, and Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. I think it’s a book that everyone interested in current American cinema would find stimulating.

You can find out more about it, and read an excerpt, here. Congratulations, J. J.!

Movies still matter

Kristin here—

I don’t know whether I should be grateful or not when I read the film trade journals or major newspapers and run across columns bemoaning the decline of the cinema. On the one hand, these give me plenty of fodder for blogging. On the other, they promote a false impression that the movie industry and the art form in general are in far worse shape than they really are.

One recent case in point is Neil Gabler’s “The movie magic is gone,” from February 25, where he says that movies have lost their previous importance in American society and are less and less relevant to our lives.

Gabler makes some sweeping claims. Movie attendance is down because movies have lost the importance they once had in our culture. Our obsession with stars and celebrities has replaced our interest in the movies that create them. Niche marketing has replaced the old “communal appeal” of movies. The internet intensifies that division of audiences into tiny groups and fosters a growing narcissism among consumers of popular culture. Audiences have become less passive, creating their own movies for outlets like YouTube. In videogames, people’s avatars make them stars in their own right, and the narratives of games replace those of movies.

Films will survive, Gabler concludes, but they face “a challenge to the basic psychological satisfactions that the movies have traditionally provided. Where the movies once supplied plots, there are alternative plots everywhere.” This epochal challenge, he says, “may be a matter of metaphysics.”

All this is news to me, and I think I have been paying fairly close attention to what has been going on in the moviemaking sphere over the past ten years—the period over which Gabler claims all this has been happening. Evidence suggests that all of his points are invalid.

1. Gabler states that “the American film industry has been in a slow downward spiral.” Based on figures from Exhibitors Relations, a box-office tracking firm, attendance at theaters fell from 2005 (a particularly down year) to 2006. A Zogby survey found that 45% of Americans had decreased their movie-going over the past five years, especially including the key 18-24-year-old audience. “Foreign receipts have been down, too, and even DVD sales are plateauing.” Such a broad decline “suggests that something has fundamentally changed in our relationship to the movies.”

Turning to a March 6 Variety article by Ian Mohr, “Box office, admissions rise in 2006,” we read a very different account of recent trends. According to the Motion Picture Association of America, admissions rose, “with 1.45 billion tickets sold in 2006—ending a three-year downward trend.” Foreign markets improved as well, “where international box office set a record of $16.33 billion as it jumped 14% from the 2005 total.” Within the U.S., grosses rose 5.5% over 2005.

We should keep in mind that part of the perception of a recent decline comes from the fact that 2002 was a huge year for box-office totals, mainly stemming from the coincidence of releases of entries in what were then the four biggest franchises going: Spider-man, The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and Star Wars. There was almost bound to be a decline after that. Such films make so much money that the fluctuations in annual box-office receipts in part reflect the number of mega-blockbusters that appear in a given year.

Looking at the longer terms, though, the biggest decline in U.S. movie-going was in the 1950s, as television and other competing leisure activities chipped away at audiences. Even so, the movies survived and from 1960 onward annual attendance hovered at just under a billion people. From 1992 on, a slow rise occurred, until by 1998 it reached roughly 1.5 billion and has hovered around that figure ever since, with a peak in 2002 at 1.63 billion. Variety’s figure of 1.45 billion for 2006 fits the pattern perfectly. In short, there has been no significant fall-off since the 1950s. (See the appendix in David’s The Way Hollywood Tells It for a year-by-year breakdown.) The article also states that industry observers expect 2007 to be especially high, given the Harry Potter, Spider-man, and Pirates of the Caribbean entries due out this year. About a year from now, expect pundits to be seeking reasons within the culture why movie-going is up. I suspect they will find that we are looking for escapism. Safe enough. When aren’t we?

Apart from theatrical attendance figures, let’s not forget that more people are watching the same movies on DVDs and on bootleg copies that don’t get into the official statistics.

2. Gabler claims that movies are no longer “the democratic art” that they were in the 20th Century. During that century, even faced with the introduction of TV, “the movies still managed to occupy the center of American life….A Pauline Kael review in the New Yorker could once ignite an intellectual firestorm … People don’t talk about movies the way they once did.”

Maybe the occasional Kael review created debate, as when she claimed that Last Tango in Paris was the “Rite of Spring” of the cinema. I think we all know by now that she was wrong. A lot of us even knew it at the time, and it’s no wonder that people argued with her. I doubt that attempts to refute her claims there or in other reviews reflected much about the health of the general population’s enthusiasm for movies.

More crucially, however, people do still talk about the movies, and lively debates go on. It’s just that now much of the discussion happens on the internet, on blogs and specialized movie sites, and in Yahoo! groups. (Who would have thought that David’s entry on Sátántango would be popular, and yet there turn out to be quite a few people out there passionately interested in Tarr’s film.)

Some would see the health of movie fandom on the internet as a sign that the cinema has become more democratic than ever. Now it’s not just casual water-cooler talk or a group of critics arguing among themselves. Anyone can get involved. The results range from vapid to insightful, but there’s an immense amount of discussion going on.

3. Interest in movies has eroded in part due to what Gabler has termed “knowingness.” By this he means the delight people take in knowing the latest gossip about celebrities. Movies have declined in importance because they exist now in part to feed tabloids and entertainment magazines.

“Knowingness” is basically a taste for infotainment. Infotainment had been around in a small way since before World War I in the form of fan magazines and gossip columns. It really took off beginning in the 1970s, with the rise of cable and the growth of big media companies that could promote their products—like movies—across multiple platforms. (I trace the rise of infotainment in Chapter 4 of The Frodo Franchise.) It’s not clear why one should assume that a greater consumption of infotainment leads to less interest in going to movies.

People in the film industry seem to assume the opposite. Studio publicity departments and stars’ personal publicity managers feed the gossip outlets, in part to control what sorts of information get out but mainly because those outlets provide great swathes of free publicity. With the rise of new media, there are more infotainment outlets appearing all the time. Naturally this trend is obvious even to those of us who don’t care about Britney’s latest escapade. But I doubt that watching Britney coverage actually makes people less inclined to go to, say, The Devil Wears Prada, one of the mid-range surprise successes that helped boost 2006’s box-office figures.

4. Movies have lost their “communal appeal” in part because the public has splintered into smaller groups, and the industry targets more specialized niche markets. According to Gabler, “the conservative impulse of our politics that has promoted the individual rather than the community has helped undermine movies’ communitarian appeal.”

Let’s put aside the idea that conservative politics erode the desire for community. The extreme right wing has certainly put enough stress on community and has banded together all too effectively to promote their own mutual interests lately. But is the industry truly marketing primarily to niche audiences?

Of course there are genre films. There always have been. Some appeal to limited audiences, as with the teen-oriented slasher movie. Yet despite the continued production of low-budget horror films, comedies, romances, and so on, Hollywood makes movies aimed at the “family” market because so many moviegoers fit into that category. Most of the successful blockbusters of recent years have consistently been rated PG or PG-13. According to Variety, 85% of the top 20 films of 2006 carried these ratings. Pirates of the Caribbean, Spider-man, Harry Potter—these are not niche pictures, though distributors typically devise a series of marketing strategies for each film, with some appealing to teen-age girls, others to older couples, and so on.

(An important essay by Peter Krämer discusses blockbusters with broad appeal: “Would you take your child to see this film? The cultural and social work of the family-adventure movie,” in Steve Neale and Murray Smith’s anthology, Contemporary Hollywood Cinema, published by Routledge in 1998.)

The result is that, despite the fact that niche-oriented films appear and draw in a limited demographic, there are certain “event” pictures every year that nearly everyone who goes to movies at all will see—more so than was probably the case in the classic studio era. Those films saturate our culture, however briefly, and surely they “enter the nation’s conversation,” as Gabler claims “older” films like The Godfather, Titanic, and The Lord of the Rings did. By the way, the last installment of The Lord of the Rings came out only a little over three years ago. Surely the vast cultural upheaval that the author posits can’t have happened that quickly.

5. The internet exacerbates this niche effect by dividing users into tiny groups and creates a “narcissism” that “undermines the movies.”

See number 2 above. I don’t know why participating in small group discussions on the internet should breed narcissism any more than would a bunch of people standing around an office talking about the same thing. In fact, there are thousands of people on the internet spending a lot of their own time and effort, many of them not getting paid for it, providing information and striving to interest others in the movies they admire.

The internet allows likeminded people to find each other with blinding speed. Often fans will stress the fact that what they form are communities. They delight in knowing that many share their taste and want to interact with them. Some of these people no doubt have big egos and are showing off to whomever will pay attention. Narcissism, however, implies a solitary self-absorption that seems rare in online communities.

A great many of these communities form around interest in movies. In this way, the internet has made movies more important in these people’s lives, not less.

6. Audiences have become active, creating their own entertainment for outlets like YouTube, and are hence less interested in passive movie viewing. These are situations “in which the user is effectively made into a star and in which content is democratized.”

No doubt more people are writing, composing, filming, and otherwise being creative because of the internet. Some of this creativity and the consumption of it by internet users takes up time they could be using watching movies.

Yet anyone who visits YouTube knows that a huge number of the clips and shorts posted there are movie scenes, trailers, music videos based on movie scenes, little films re-edited out of shots taken from existing movies, and so on. In some cases the makers of these films have pored over the original and lovingly re-crafted it in very clever ways. A lot of the creativity Gabler notes actually is inspired by movies. Some people post their films on YouTube because they are aspiring movie-makers hoping to get noticed. The movie industry as a whole is not at odds with YouTube and other sites of fan activity, despite the occasional removal of items deemed to constitute piracy.

7. New media allow these active, narcissistic spectators to star in their own “alternative lives.” “Who needs Brad Pitt if you can be your own hero on a video game, make your own video on YouTube or feature yourself on Facebook?”

In discussing videogames, Gabler perpetuates the myth that “video games generate more income than movies.” This is far from being true, and hence his claim that videogames are superseding movies is shaky. (I debunk this myth in Chapter 8 of The Frodo Franchise.)

Even the spread of videogames does not necessarily mean that fans are deserting movies. On the contrary, there is evidence that people who consume new media also consume the old medium of cinema. Mohr’s Variety article reports on a recent study by Nielsen Entertainment/NRG: “Somewhat surprisingly, the same study revealed that the more home entertainment technology an American owns, the higher his rate of theater attendance outside the home. People with households containing four or more high-tech components or entertainment delivery systems—from DVD players to Netflix subscriptions, digital cable, videogame systems or high-def TV—see an average of three more films per year in theaters than people with less technology available in their homes.”

Apart from the shaky factual basis of the column, what does the end-of-cinema genre tell us about how trends get interpreted by commentators?

As I pointed out in my March 9 entry, some commentators explain perceived trends in film by generalizing about the content of the movies themselves. “As soon as some trend or apparent trend is spotted, the commentator turns to the content of the films to explain the change. If foreign or indie films dominate the awards season, it must be because blockbusters have finally outworn their welcome. If foreign or indie films decline, it must be because audiences want to retreat from reality into fantasy. It’s an easy way to generate copy that sounds like it’s saying something and will be easily comprehensible to the general reader.”

Gabler is arguing for something different—something that, if it were true would be more depressing for those who love movies. He’s not positing that movies have failed to cater to the national psyche. He’s claiming that other forces, largely involving new media, have changed that national psyche in a way which moviemakers could never really cope with. Cinema as an art form cannot provide what these other media can, and spectators caught up in the options those media offer will never go back to loving movies, no matter what stories or stars Hollywood comes up with. By his lights, the movies are apparently doomed to a long, irreversible decline.

Hollywood has what I think is a more sensible view of new media. Games, cell phones, websites, and all the platforms to come are ways of selling variants of the same material. Film plots are valuable not just as the basis for movies but because they are intellectual property that can be sold on DVD, pay-per-view, and soon, over the internet. They can be adapted into video games, music videos, and even old media products like graphic novels and board games.

Not only Hollywood but the new media industries have already analyzed the changing situation and come up with new approaches to dealing it. Check out IBM’s new Navigating the media divide: Innovating and enabling new business models. Those models include “Walled communities,” “Traditional media,” “New platform aggregation,” and “Content hyper-syndication,” which, the authors predict, “will likely coexist for the mid term.”

In other words, traditional media like the cinema aren’t dying out. No art form that has been devised across the history of humanity has disappeared. Movies didn’t kill theater, and TV didn’t kill movies. It’s highly significant that the main components of new media—computers, gaming consoles, and the internet—have all added features that allow us to watch movies on them.

The big movies still get more press coverage than the big videogames partly because they usually are the source of the whole string of products. If a movie doesn’t sell well, it’s likely that its videogame and its DVD and all its other ancillaries won’t either. That is a key word, for many of the new media that Gabler mentions produce the ancillaries revolving around a movie. So far, very few movies are themselves ancillary to anything generated with new media. If you doubt that, check out Box Office Mojo’s chart of films based on videogames, which contains all of 22 entries made since 1989.

One final point. Film festivals are springing up like weeds around the world. Enthusiasts travel long distances to attend them. That’s devotion to movies. From last year’s Wisconsin Film Festival, add 26,000 tickets sold to that 1.5 billion attendance figure.

Movies still matter enormously to many people. New media have given them new ways to reach us, and us new ways to explore why they matter.

This is your brain on movies, maybe

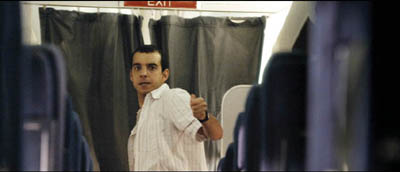

United 93.

From DB:

Normally we say that suspense demands an uncertainty about how things will turn out. Watching Hitchcock’s Notorious for the first time, you feel suspense at certain points–when the champagne is running out during the cocktail party, or when Devlin escorts the drugged Alicia out of Sebastian’s house. That’s because, we usually say, you don’t know if the spying couple will succeed in their mission.

But later you watch Notorious a second time. Strangely, you feel suspense, moment by moment, all over again. You know perfectly well how things will turn out, so how can there be uncertainty? How can you feel suspense on the second, or twenty-second viewing?

I was reminded of this problem watching United 93, which presents a slightly different case of the same phenomenon. Although I was watching it for the first time, I knew the outcomes of the 9/11 events it portrays. I knew in advance that the passengers were going to struggle with the hijackers and deflect the plane from its target, at the cost of all their lives. Yet I felt what seemed to me to be authentic suspense at key moments. It was as if some part of me were hoping against hope, as the saying goes, that disaster might be avoided. And perhaps the film’s many admirers will feel something like that suspense on repeated viewings as well.

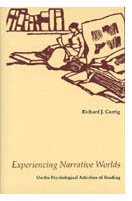

Psychologist Richard Gerrig in his book Experiencing Narrative Worlds calls this anomalous suspense: feeling suspense when reading or viewing, although you know the outcome.

Anomalous suspense: Some theories

Anomalous suspense has been fairly important in the history of film. One of the most famous instances in the early years of feature film is the assassination of President Lincoln in Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915). Griffith prolongs the event with crosscutting and detail shots in a way that promotes suspense, even though we know that Booth will murder Lincoln. Anomalous suspense, of course, isn’t specific to movies; we can feel this way reading a familiar book or watching a TV docudrama about historical events. Young children listening to the story of Little Red Riding Hood seem to be no less wrought up on the umpteenth version than on the first.

This is very odd. How can it happen?

One answer is simple: What you’re feeling in a repeat viewing, or a viewing of dramatized historical events, isn’t suspense at all. Robert Yanal has explained this position here. He suggests that you’re responding to other aspects of the story. Maybe in rewatching Notorious you’re enjoying the unfolding romance, and you attribute your interest to suspense. And there are feelings akin to suspense that don’t rely on uncertainty–dread, for instance, in facing likely doom. (This is my example, not Yanal’s, but I think it’s plausible.) Another possibility Yanal floats is that on repeat viewings, you have actually forgotten what happens next, or how the story ends.

Yanal’s account doesn’t fully satisfy me, largely because I think that most people know what suspense feels like and attest to feeling it on repeat viewings. I did feel some dread in watching United 93, but I think that was mixed with a genuine feeling of suspense–a momentary, if illogical uncertainty about the future course of events. In any case, I didn’t forget what happened at the end; I expected it in quite a self-conscious way.

Yanal’s account doesn’t fully satisfy me, largely because I think that most people know what suspense feels like and attest to feeling it on repeat viewings. I did feel some dread in watching United 93, but I think that was mixed with a genuine feeling of suspense–a momentary, if illogical uncertainty about the future course of events. In any case, I didn’t forget what happened at the end; I expected it in quite a self-conscious way.

Richard Gerrig, the psychologist who gave anomalous suspense its name, offers a different solution. He posits that in general, when we reread a novel or rewatch a film, our cognitive system doesn’t apply its prior knowledge of what will happen. Why? Because our minds evolved to deal with the real world, and there you never know exactly what will happen next. Every situation is unique, and no course of events is literally identical to an earlier one. “Our moment-by-moment processes evolved in response to the brute fact of nonrepetition” (Experiencing Narrative Worlds, 171). Somehow, this assumption that every act is unique became our default for understanding events, even fictional ones we’ve encountered before.

I think that Gerrig leaves this account somewhat vague, and its conception of a “unique” event has been criticized by Yanal, in the article above. But I think that Gerrig’s invocation of our evolutionary history is relevant, for reasons I’ll mention shortly.

Suspense as morality, probability, and imagination

The most influential current theory of suspense in narrative is put forth by Noël Carroll. The original statement of it can be found in “Toward a Theory of Film Suspense” in his book Theorizing the Moving Image. Carroll proposes that suspense depends on our forming tacit questions about the story as it unfolds. Among other things, we ask how plausible certain outcomes are and how morally worthy they are. For Carroll, the reader or viewer feels suspense as a result of estimating, more or less intuitively, that the situation presents a morally undesirable outcome that is strongly probable.

When the plot indicates that an evil character will probably fail to achieve his or her end, there isn’t much suspense. Likewise, when a good character is likely to succeed, there isn’t much suspense. But we do feel suspense when it seems that an evil character is likely to succeed, or that a good character is likely to fail. Given the premises of the situation, the likelihood is very great that Alicia and Devlin will be caught by Sebastian and the Nazis, so we feel suspense.

What of anomalous suspense? Carroll would seem to have a problem here. If we know the outcome of a situation because we’ve seen the movie before, wouldn’t our assessments of probability shift? On the second viewing of Notorious, we can confidently say that Alicia and Devlin’s stratagems have a 100% chance of success. So then we ought not to feel any suspense.

Carroll’s answer is that we can feel emotions in response to thoughts as well as beliefs. Standing at a viewing station on a mountaintop, safe behind the railing, I can look down and feel fear. I don’t really believe I’ll fall. If I did, I would back away fast. I imagine I’m going to fall; perhaps I even picture myself plunging into the void and, a la Björk, slamming against the rocks at the bottom. Just the thought of it makes my palms clammy on the rail.

Carroll points out that imagining things can arouse intense emotions, and his book The Philosophy of Horror uses this point to explain the appeal of horrific fictions. The same thing goes, more or less, for suspense. If the uncertainty at the root of suspense involves beliefs, then there ought to be a problem with repeat viewings. But if you merely entertain the thought that the story situation is uncertain, then you can feel suspense just as easily as if you entertained the thought that you were falling off the mountain top.

In other words, the relation between morality and probability in a suspenseful situation is offered not to your beliefs but to your imagination. When you judge that in this story the good is unlikely to be rewarded, you react appropriately–regardless of what you know or believe about what happens next. Carroll outlines this view in his book Beyond Aesthetics.

How are we encouraged to entertain such thoughts in our imagination? Carroll indicates that the film or piece of literature needs to focus our attention on the suspenseful factors at work, thus guiding us to the appropriate thoughts about the situation. There might, though, be more than attention at work here.

The firewall

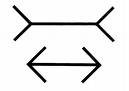

In Consciousness and the Computational Mind (1987), psychologist Ray Jackendoff asked why music doesn’t wear out. When composers write tricky chord progressions or players execute startling rhythmic changes, why do those surprise or thrill us on rehearing? Similarly, you’ve seen the Müller-Lyer optical illusion many times, and you know that the two horizontal lines are of equal length. You can measure them.

Yet your eyes tell you that the lines are of different lengths and no knowledge can make you see them any other way. This illusion, in Jerry Fodor‘s phrase, is cognitively impenetrable.

We can reexperience familiar music or fall prey to optical illusions because, in essence, our lower-level perceptual activities are modular. They are fast and split up into many parallel processes working at once. They’re also fairly dumb, quite impervious to knowledge. Jackendoff suggests that our musical perception, like our faculties for language and vision, relies on

a number of autonomous units, each working in its own limited domain, with limited access to memory. For under this conception, expectation, suspense, satisfaction, and surprise can occur within the processor: in effect, the processor is always hearing the piece for the first time (245).

The modularity of “early vision”–the earliest stages of visual processing–is exhaustively discussed by Zenon W. Pylyshyn in Seeing and Visualizing: It’s Not What You Think (2006).

As students of cinema, we’re familiar with the fact that vision can be cognitively impenetrable. We know that movies consist of single frames, but we can’t see them in projection; we see a moving image.

Early vision works fast and under very basic, hard-wired assumptions about how the world is. That’s because our visual system evolved to detect regularities in a certain kind of environment. That environment didn’t include movies or cunningly designed optical illusions. So there might be a kind of firewall between parts of our perception and our knowledge or memory about the real world.

Daniel J. Levitin’s lively book, This is Your Brain on Music summarizes the neurological evidence for this firewall in our auditory system. When we listen to music, a great deal happens at very low levels. Meter, pitch, timbre, attack, and loudness are detected, dissected, and reconstructed across many brain areas. The processes runs fast, in parallel, and we have very little voluntary control of them, let alone awareness of them. Of course higher-level processes, like knowledge about the piece, the composer, or the performer, feed into the whole activity. But that’s inevitably running on top of the very fast uptake, disassembly, and reassembly of sensory information. Go here for more information on the book, including some music videos.

Daniel J. Levitin’s lively book, This is Your Brain on Music summarizes the neurological evidence for this firewall in our auditory system. When we listen to music, a great deal happens at very low levels. Meter, pitch, timbre, attack, and loudness are detected, dissected, and reconstructed across many brain areas. The processes runs fast, in parallel, and we have very little voluntary control of them, let alone awareness of them. Of course higher-level processes, like knowledge about the piece, the composer, or the performer, feed into the whole activity. But that’s inevitably running on top of the very fast uptake, disassembly, and reassembly of sensory information. Go here for more information on the book, including some music videos.

So here’s my hunch: A great deal of what contributes to suspense in films derives from low-level, modular processes. They are cognitively impenetrable, and that creates a firewall between them and what we remember from previous viewings.

A suspense film often contains several very gross cues to our perceptual uptake. We get tension-filled music and ominous sound effects, such as low-bass throbbing. We get rapid cutting and swift camera movements. Often the shots are close-ups, as in Notorious‘s wine-cellar scene and during the characters’ final descent of the staircase. Close-ups concentrate our vision on one salient item, creating the attentional focus Carroll emphasizes. The shots are often cut together so fast that we barely have time to register the information in each one.

This isn’t to say that the action itself has to be fast. The action in the Hitchcock scenes isn’t rapid, but its stylistic treatment is. In typical suspense scenes, our “early vision” and “early audition,” biased toward quick pickup, are given rapid-fire bursts of information while our slower, deliberative processes are put on hold. This is happening in the Birth of a Nation assassination scene, as well as in the frantic second half of United 93.

Further, what is shown can push our processing as well. Seeing people’s facial expressions touches off empathy and emotional contagion, perhaps through mirror neurons.

This tendency may explain why we can, momentarily, feel a wisp of empathy for unsympathetic characters. When their expressions show fear, we detect and resonate to that even if we aren’t rooting for them to succeed.

We may also be responding to some very basic scenarios for suspenseful action. Imagine dangling at a great height; “hanging” is the root of the word suspense. Or imagine hurtling toward an obstruction, or being stalked by an animal, or being advanced upon by a looming figure. As prototypes of impending danger, these events may in themselves trigger a minimal feeling of suspense. And such situations are part of filmic storytelling from its earliest years.

Maybe we’re predisposed to find facial expressions and dangerous situations salient because of our evolutionary history, or maybe they’re learned from a very young age. Either way, such responses don’t require much deliberate thinking. They just trigger rapid responses that we can reflect upon later.

Stylistic emphasis and prototype situations surely help the attention-focusing that Carroll discusses. But I’m suggesting something stronger: Many of these cues don’t merely guide our attention to the critical suspense-creating factors in the scene. These cues are arresting and arousing in themselves. They trigger responses that, in the right narrative situation, can generate suspense, regardless of whether we’ve seen the movie before.

Beyond these cues, of course we have to understand the story to some degree. Probably some of the aspects of storytelling that Carroll, Gerrig, and others (including me) have highlighted come into play. As Hitchcock famously pointed out, suspense sometimes depends on telling the viewer more than the character knows. We have to see the bomb under the table that the character doesn’t know about. Suspense is also conjured up by Carroll’s ratio of morality to probability, our real-world understanding of deadlines, and other higher-order aspects of comprehension. In addition, our knowledge of how stories are typically told probably shapes our uptake. We expect suspense to be a part of a film, and so we’re alert for cues that facilitate it.

Involuntary suspense

So I’m hypothesizing that part of the suspense we feel in rewatching a film depends on fast, mandatory, data-driven pickup. That activity responds to the salient information without regard to what we already know.

According to this argument, the sight of Eve Kendall dangling from Mount Rushmore will elicit some degree of suspense no matter how many times you’ve seen North by Northwest, and that feeling will be amplified by the cutting, the close-ups, the music, and so on. Your sensory system can’t help but respond, just as it can’t help seeing equal-length lines in the pictorial illusion. For some part of you, every viewing of a movie is the first viewing.

This tendency may hold good for other emotions than suspense. In the psychological jargon I adopted in Narration in the Fiction Film, experiencing a narrative is likely to be both a bottom-up process and a top-down process. Suspense and other emotional effects in film may depend not only on conceptual judgments about uncertainty, likelihood, and so on. They may also depend on quick and dirty processes of perception that don’t have much access to memory or deliberative thinking.

Film works on our embodied minds, and the “embodied” part includes a wondrous number of fast, involuntary brain activities. This process gives filmmakers enormous power, along with enormous responsibilities.

PS: 9 March. Jason Mittell writes a comment, based on his recent research on TV fans’ attitudes toward spoilers, at his site here. More later, I hope, when I have a chance to assimilate his argument.

Homage to Mme. Edelhaus

Why are Americans polarized between francophobia and francophilia? Some people mock the French for liking Jerry Lewis, when most French people probably don’t even know who he is. Others think that France is the repository of world culture and represents the finest in writing about the arts, even though the Parisian intelligentsia can be pretentious and hermetic.

But we must face facts. When it comes to cinephilia, the French have no equals. They grant film a respect that it wins nowhere else. Spend a year, or even a month, in Paris, and you will feel like a Renaissance prince. This is a city where one lonely screen can run tattered prints of One from the Heart and Hellzapoppin!, once a week, indefinitely.

My first trip was too brief, only a week in 1970, but my second one—four weeks of dissertation research in 1973—left me exhausted. Reading Pariscope on the way in from the airport, I learned about a Tex Avery festival. I checked into my hotel and Métro’d to the theatre, where I and a bunch of moms and kids gazed in rapture upon King-Size Canary. Another time, also coming in from the airport, Kristin and I passed a marquee for King Hu’s Raining in the Mountain. Next stop, Raining in the Mountain. My memories of The Naked Spur, Ministry of Fear, Liebelei, Tati’s Traffic, and Vertov’s Stride Soviet! are inextricable from the Parisian venues in which I saw them.

Sound like a lament for days gone by? Nope. You can find the same variety on offer today. Of course the two monthlies, Cahiers du cinéma and Positif, have to take a lot of credit for this. Add Traffic, Cinéma, and several other ambitious journals, and you get a film culture unrivalled in the world.

Critics from Louis Delluc onward have led thousands of readers toward appreciating the seventh art. Historians like Georges Sadoul, Jean Mitry, Laurent Mannoni, Francis Lacassin, and others have enlightened us for decades. Academic film analysis would not be what it is without Raymond Bellour, Noel Burch, Marie-Claire Ropars, Jacques Aumont, and a host of other scholars. Above all stands André Bazin, the greatest theorist-critic we have had.

And the books! Arts-and-sciences publishing receives government subsidies; the French understand that books contribute to the public good. There are plenty of worse ways to spend tax dollars (e.g., trumped-up military invasions). The French, like the Italians, have created an ardent translation culture too. If you can’t read something in Russian or German, there’s a good chance it’s available in French.

I was reminded of the glories of Gallic film publishing when the mailman tottered to my door this week with twenty-two pounds worth of recent items I’d ordered. I haven’t even read them yet; otherwise, they’d be filed with Book Reports. Instead I want to spend today’s blog celebrating them as fruits of an ambition that has no counterpart in English-language publishing. All are grand and gorgeous and informative to boot.

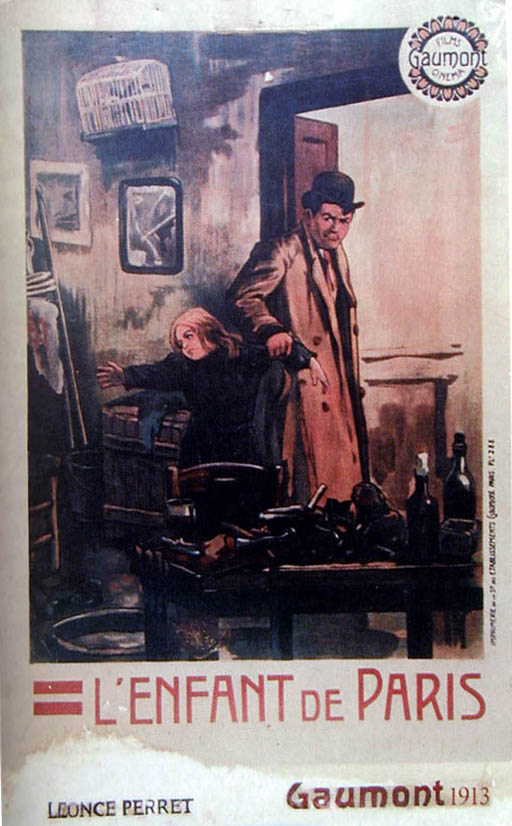

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

A biographical study of a Gaumont director still too little known. Perret was second only to Feuillade at Gaumont, and he performed as a fine comedian as well. His shorts are charming, and his longer works, like L’enfant de Paris (1913), remain remarkable for their complex staging and cutting. After a thriving career in France, Perret came to make films in America, including Twin Pawns (1919), a lively Wilkie Collins adaptation. He returned to France and was directing up to his death in 1935.

Although the text seems a bit cut-and-paste, Taillé has included many lovely posters and letters, along with a detailed filmography, full endnotes, and a vast bibliography. It compares only to that deluxe career survey of the silent films of Raoul Walsh, published by Knopf. . . .Oh, wait, there’s no such book. . . .Think there ever will be?

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

A luscious catalogue of an exposition tracing visual sources of Disney’s animation. Illustrated with sketches, concept paintings, and character designs from the Disney archives, this volume shows how much the cartoon studio owed to painting traditions from the Middle Ages onward. It includes articles on the training schools that shaped the studio’s look, on European sources of Disney’s style and iconography, on architecture, on relations with Dalí, and on appropriations by Pop Artists. There’s also a filmography and a valuable biographical dictionary of studio animators.

Some of the affinities seem far-fetched, but after Neil Gabler’s unadventurous biography, a little stretching is welcome. This exhibition (headed to Montreal next month) answers my hopes for serious treatment of the pictorial ambitions of the world’s most powerful cartoon factory. The catalogue is about to appear in English–from a German publisher.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

The authors of a lengthy study of Citizen Kane now take us through the production process of each of Welles’ works. They have stuffed their book with script excerpts, storyboards, charts, timelines, and uncommon production stills.

The text, on my cursory sampling, will seem largely familiar to Welles aficionados; the frames from the actual films betray their DVD origins; and I would like to have seen more depth on certain stylistic matters. (The authors’ account of the pre-Kane Hollywood style, for instance, is oversimplified.) Yet the sheer luxury of the presentation overwhelms my reservations. A colossal filmmaker, in several senses, deserves a colossal book like this.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

In the same series as the Welles volume, even more imposing. If you want to know the shooting schedule for Alphaville or check the retake report for La Chinoise (these are eminently reasonable desires), here is the place to look. Detailed background on the production of every 1960s Godard movie, with many discussions of the creative choices at each stage. Once more, stunningly mounted, with lots of color to show off posters and production stills.

Anybody who thinks that Godard just made it up as he went along will be surprised to find a great degree of detailed planning. (After all, the guy is Swiss.) Yet the scripts leave plenty of room to wiggle. “The first shot of this sequence,” begins one scene of the Contempt screenplay, “is also the last shot of the previous sequence.” Soon we learn that “This sequence will last around 20-30 minutes. It’s difficult to recount what happens exactly and chronologically.”

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

The avoirdupois champ of my batch. The French were early admirers of modern Hong Kong cinema, but their reference works lagged behind those of Italy, Germany, and the US. (Most notable of the last is John Charles’ Hong Kong Filmography, 1977-1997.) More recently the French have weighed in, literally. 2005 gave us Christophe Genet’s Encyclopédie du cinéma d’arts martiaux, a substantial (2 lbs.) list of films and personalities, with plots, credits, and French release dates.

Newer and niftier, the Gouneau/ Amara volume covers much more than martial arts, and so it strikes my tabletop like a Shaolin monk’s fist. There are lovely posters in color and plenty of photos of actors that help you identify recurring bit players. Yet this is more than a pretty coffee-table book. It offers genre analysis, history, critical commentary, biographical entries, surveys of music, comments on television production, and much more. It has abbreviated lists of terms and top box-office titles, as well as a surprisingly detailed chronology.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Mme. Edelhaus was my high school French teacher. A stout lady always in a black dress, she looked like the dowager at the piano during the danse macabre of Rules of the Game. She was mysterious. She occasionally let slip what it was like to live under Nazi occupation, telling us how German soldiers seeded parks and playgrounds with explosives before they left Paris. When I asked her what avant-garde meant, she replied that it was the artistic force that led into unknown regions and invited others to follow–pause–“in the unlikely event that they will choose to do so.”

For three years Mme. Edelhaus suffered my execrable pronunciation. When I tried to make light of my bungling, she would ask, “Dah-veed, why must you always play the fool?”

I suppose I’m still at it. But thanks largely to her I’m able to read these books as well as look at them. She opened a path that’s still providing me vistas onto the splendors of cinema.