Archive for May 2007

Movies on the radio

DB here:

There’s no shortage of podcast film reviews, but I confess that I’ve listened to only a few. I’m just not that interested in following a movie review at the pace of a speaking voice; I prefer skimming print to pluck out the good parts. And I’m on the lookout for ideas and information, not only opinions. I want to learn new stuff. So my iPod favors shows that center on interviews with directors, writers, and moguls. The two programs that I like best are produced by the extraordinary KCRW in Santa Monica and are also available from iTunes.

One is The Business, hosted by Claude Brodesser-Akner (above top). Armed with solid research and snappy patter, he comes across as sharp and a little insolent, a quality always welcome in an interviewer. After a disrespectful roundup called The Hollywood News Caravan, Brodesser-Akner devotes most of the rest of a show to a major topic. You can survey several programs here.

One is The Business, hosted by Claude Brodesser-Akner (above top). Armed with solid research and snappy patter, he comes across as sharp and a little insolent, a quality always welcome in an interviewer. After a disrespectful roundup called The Hollywood News Caravan, Brodesser-Akner devotes most of the rest of a show to a major topic. You can survey several programs here.

A recent installment focused on the latest cycle of teenage horror, with input from Eli Roth, director of the Hostel films, and Oren Koules, producer of the Saw series. They talk about marketing directly to the fan sites and avoiding the expensive TV ads that studios bombard the public with. Putting banners and flashing ads on the horror sites, Roth says, attracts the same eyeballs as an ad on Lost, but for a fraction of the price. Koules:

Playing [an ad] on a Friends rerun doesn’t help anyone.

Likewise for budgets overall. Roth:

The scare is the star. . . .Nobody wants to see a $50 million version of Saw II. . . . People aren’t paying for big special effects. They’re paying to be scared.

In one of the most interesting stretches of the interview, Roth and Koules explain how they negotiate with the MPAA ratings board. According to the filmmakers, the board completely understands what they want to give the audience and the board is willing to cooperate. Koules:

We’re very respectful of the process. . . . And they know that we kind of know the market.

The fact that the films are designed for an R rating makes the task easier, of course, but sexual violence remains the most sensitive area. Roth:

They’re reflecting what the parents of America are going to say. . . . Just look at the culture. We have violence on television, people watch it—no problem. The stuff that I did in Hostel 1 is now on 24. [But] Janet Jackson shows her nipple and Congress is in session meeting about it and there’re all sorts of fines. So [the raters] really are just reflecting the temperature of the culture.

More proof that the MPAA and the ratings board find it easier to accept the excesses of genre filmmaking than to support the naughty indie material Kirby Dick surveys in This Film Is Not Yet Rated. Why should bathing in blood rate an R while boinking, boffing, and the Wild Mambo get threatened with an NC-17?

I’ve been following The Business for a year or so, but in May while traveling in New Zealand I started listening to The Treatment, hosted by Elvis Mitchell (above, bottom). For all the superstar press he gets, he comes across as soft-spoken, thoughtful, and probing. It’s very unusual for a journalist-critic to pose questions about film craft and aesthetics, but Mitchell wades right in.

I’ve been following The Business for a year or so, but in May while traveling in New Zealand I started listening to The Treatment, hosted by Elvis Mitchell (above, bottom). For all the superstar press he gets, he comes across as soft-spoken, thoughtful, and probing. It’s very unusual for a journalist-critic to pose questions about film craft and aesthetics, but Mitchell wades right in.

He asks Robert Rodriguez, for instance, how music shapes a film’s editing rhythms. After acknowledging that he plays music for actors on the set (as Wong Kar-wai does), Rodriguez adds:

I’ll be doing music all the way through the process of making a movie. And then I’ll usually just start editing first. Then I’ll put the edit into my music system, write the music for it, and if I like how the music is driving the scene and if the edits don’t match, I’ll go and adjust the edits. So I tell other composers—they’re probably very jealous—that I’m the composer who can tell the editor to go back and make the picture fit the music.

Another example: A while back, I posted a blog entry on how framing and the choice of lenses can create comic effects. I illustrated with an instance from Shaun of the Dead. Serendipitously, last week I discovered Mitchell’s recent interview with Shaun‘s director Edgar Wright, who acknowledged that the idea was central to his filmmaking.

The thing I’ve been trying to do in Spaced and Shaun and Hot Fuzz is the camera almost becomes a personality. Not only is the script funny and the performances are funny, but the compositions are funny—the framing of the shots is funny. . . . I remember seeing Raising Arizona and thinking, “Oh, why isn’t all comedy shot like this? It’s amazing.” . . . You get the actors to think of the camera as another performer that they’re blocking with.

The entire conversation seems to me mandatory for students of film. Coaxed by Mitchell, Wright supplies specifics about planning a shoot, varying camera setups, and the “epileptic” style of the contemporary action films that Hot Fuzz is satirizing. Wright even seems to like Domino, which shows that he can see virtues in extravagance.

So I recommend both The Business and The Treatment to anyone who wants to get filmmakers’ thoughts about current trends in movie tradecraft.

Intensified continuity revisited

DB here:

We’re just beginning to understand the history of film forms, but some trends in Hollywood already seem clear. During the late 1910s American filmmakers synthesized an approach to cinematic storytelling that relied on continuity editing, the practice of breaking a scene into matched shots in order to highlight character action and reaction. In the years that followed, this editing strategy became the dominant approach to mass-market filmmaking across the world. Many historians and theorists believed that editing was the essence of cinema itself.

When sound arrived in the late 1920s, the technology was difficult to master and consumed a lot of production time. It would have been easy for American filmmakers to shoot every scene from a single position, but instead they used multiple cameras to cover the action, much as three-camera TV handles sitcoms now. This made filming cumbersome and limited the lighting choices, but filmmakers wanted to preserve the option of cutting to closer views and fresh angles as the scene developed. Continuity editing continued through the 1930s and well beyond, with filmmakers refining it in various ways.

The strategy has proven remarkably robust. Today’s mass-audience films, from all over the world, adhere to the principles and particulars of continuity editing. Not many artistic styles, in any medium, have had such a long run.

These ideas are developed in more detail in things that Kristin and I have written. (1) Most recently my book The Way Hollywood Tells It tries to track shorter-term changes in the continuity style. I found that one handy way to do this was to look at remakes. Remakes allow us to keep story factors somewhat constant and focus on differences in visual technique. Today’s blog looks at parallel scenes from two films, an original and a remake, in order to illustrate what I’ve called “intensified continuity”—the editing style that comes to dominate American films after 1960 or thereabouts.

Dear friend….

In Ernst Lubitsch’s wonderful Shop around the Corner (1940) Kralik (James Stewart) works in a Budapest gift shop with Klara (Margaret Sullivan). They quarrel constantly. But each has an anonymous pen pal, and the relationship is growing into love. Unfortunately, we learn early on, they’re writing to each other.

On the day they’ve agreed to meet face to face, Kralik is fired. He and another salesman Pirovitch (Felix Bressart) trudge to the café where Kralik is to meet his secret friend. Kralik can’t bear to face her now that he has no job, so he wants Pirovitch to deliver a note saying he can’t come. Still, his curiosity makes him ask Pirovitch to look in the window and describe her. Pirovitch tries to soften the blow, but he has to admit that the young woman waiting with a copy of Anna Karenina and a red carnation is Klara.

Angry, Kralik takes back the note and decides to let her wait. But after Pirovitch is gone, he returns to the café and meets her—not divulging his identity, but trying some conciliatory moves.

In the silent era, Lubitsch was one of the greatest exponents of continuity editing. You need only look at The Marriage Circle or Lady Windermere’s Fan to see his quiet virtuosity. (Kristin’s Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood devotes a chapter to his cutting.) But in Shop around the Corner Lubitsch uses only two shots to present Kralik’s and Pirovitch’s conversation outside the café. A fairly distant tracking shot follows the two men to the window, then we get a very lengthy shot of the two men outside. It starts with Kralik instructing Pirovitch to check on what his correspondent looks like.

Another director would have given us point-of-view shots showing what Pirovitch sees, along with his reactions. Instead, Lubitsch keeps the emphasis on Kralik, who’s responding to Pirovitch’s reports. Consequently, Kralik’s reactions aren’t given in cut-in close-ups but rather in the prolonged two shot.

This allows both performers to act with their bodies. Bessart’s shoulders relax, for instance, when he spots Klara, as if he’s slightly recoiling. Stewart’s reactions are more varied; he leans forward eagerly and nods as Pirovitch finds the woman. He slumps, then tugs his hat when Pirovitch mentions Klara.

Kralik looks in to see for himself, and collapses a bit. He eventually relaxes when he wryly accepts the fact that his pen pal is his quarrelsome coworker.

Visually, it’s a simple scene, but it shows the power of the unvarnished two-shot.

After the two men separate, Lubitsch shifts the scene inside and gives us another sustained shot as the anxious Klara talks with a waiter. Instead of crosscutting to Kralik returning outside, Lubitsch creates a humorous shot by letting his head drift into the window behind Klara.

When Kralik goes in to meet Klara, he doesn’t tell her that he’s her pen pal, so narrationally speaking, the knowledge is unbalanced. He and we know more than Klara does, which makes her unhappiness more pathetic. It’s a wonderfully textured scene, partly because we know that each one’s annoyance with the other masks disappointment and anxiety. As the action develops, there’s somewhat more cutting, but even Lubitsch’s closer views often keep both in the frame. He saves his closest shots for the most intense exchange, when Klara mockingly refuses Kralik’s efforts at friendship. The scene will end on a painful note, with each wounding the other with hurtful remarks.

AOL buddies

As you probably know, The Shop around the Corner was remade as You’ve Got Mail. There are some important story differences. The two protagonists have other partners, and Joe Fox owns a bookstore chain that is crushing the children’s bookstore owned by Kathleen Kelly (Meg Ryan). But the parallel scene in You’ve Got Mail is remarkably similar to the one we’ve just been examining.

The sequence starts with Joe and his assistant Kevin (Dave Chappelle) approaching the coffee shop, and Joe is apprehensive—not because like Kralik he’s out of a job but because of the upheaval that meeting his email correspondent could cause in his personal life. Like Kralik, he asks his friend to peer in the window to check her out.

But Nora Ephron handles the scene quite differently than Lubitsch did. She breaks all the dialogue into several shots, mostly favoring one actor (either over-the-shoulder shots or what are called singles). The process starts during the men’s approach to the café.

Once they arrive, the staging stations Joe at the foot of a flight of stairs and Kevin at the top, so a sustained two-shot isn’t really in the cards. The pattern is that Kevin reports what he sees, and in reaction shots we see Joe’s response.

When each man looks inside, unlike Lubitsch Ephron supplies point-of-view shots of Kathleen.

Joe reacts vindictively when he learns his email correspondent is his adversary, and he returns to punish her, but not before we’re taken inside the café and watch Kathleen wait for her correspondent. Even her encounter with another customer, somewhat similar to Klara’s chat with the waiter, is broken into three shots.

When Joe arrives, his conversation with Kathleen is handled in variations of shot-reverse shot, often in fairly tight framings. Again, the closer framings accentuate the bitter insults the characters exchange.

You’ve got cutting

Both scenes run almost exactly the same length: 8:48 in Shop, 8:42 in You’ve Got. But the initial portion, showing the two men on the sidewalk, consumes only two shots in the Lubitsch and 41 shots in the Ephron. That means that Lubitsch’s average shot in the scene runs about 82 seconds, while Ephron’s runs about 4.1 seconds!

The same disparity arises in the section of the scene taking place in the café. In Shop, 14 shots treat the action inside, but in You’ve Got there are 84! Lubitsch’s shots in this portion average about 21 seconds, still very lengthy, while Ephron’s are almost exactly the same as in the earlier portion, coming in at 4.3 seconds. We tend to think that only high-octane action sequences are cut quickly, but today’s dialogue scenes are cut fast too.

In both films, actors’ line readings are very important, but in Shop, the performances include sustained passages of body language. In You’ve Got, actors act mostly with their faces. Whereas Ephron gives us singles from the start (Kevin and Joe’s approach), Lubitsch saves his close shots for the encounter between his squabbling romantic couple. There’s an effect of gradation, with the cutting building the scene visually toward a high point, that isn’t provided by Ephron.

Oddly, the modern film is less subtle than the older one. Lubitsch uses no nondiegetic music in the scene, but Ephron inserts conventionally comic music as Kevin and Joe approach and we get sorrowful music when Kathleen leaves the café in tears. Although many people think that old movies are hammy and overplayed, here it’s just the opposite. Stewart performs subtly, but Hanks, whom many take as today’s Jimmy Stewart, plays broadly, gesturing in extremis and at one point shaking the brownstone’s railing. The Lubitsch scene also makes use of dramatic pauses to a greater extent than Ephron does.

The redundancy is seen as well in Ephron’s reliance on cutting and singles. Nearly every line or reaction in the You’ve Got sequence gets a shot to itself. This isn’t unique to this film; every remake I’ve examined is cut faster than its original. Fast cutting, down to 2 or 3 seconds per shot on average, and a reliance on OTS’s and singles typify today’s intensified brand of continuity.

Silent films were cut quite fast—in America, around five seconds per shot was common—but the arrival of sound slowed down the editing pace. The good people at Cinemetrics are building a database tracking this trend, among others. But since the 1960s, things picked up in American cinema, and today it isn’t uncommon to find films with average shot lengths of 2-4 seconds….and not just action movies. Likewise, such cutting operates in conversation scenes, making it more likely that the shots are singles rather than two-shots or ensemble framings.

This “intensification” of traditional continuity tactics, I’d argue, dominates mainstream moviemaking today, and not just in the US. Such cutting can sometimes be found in the 1930s and 1940s too, but then it was one possibility within a broader range. The Lubitsch example adheres to the principles of continuity editing, but it allows for more variety of camera distance and pacing.

I don’t denounce intensified continuity as such; some films, most recently David Fincher’s fine Zodiac, make intelligent use of it. Still, with this as the dominant approach, the director’s range of choice has narrowed. When contemporary directors lengthen a take, it’s usually to create a virtuoso traveling shot. A simple framing like the one outside the cafe in Shop is very unusual nowadays. The sustained two shot is practically an endangered species.

Why? What led to these changes between the studio era and contemporary cinema? A cynic would say that, contrary to Steven Johnson, audiences have gotten dumber and need more emphasis on character action and reaction to follow what’s going on. But in The Way Hollywood Tells It I suggest that there are many factors at work in this stylistic change. The book also provides more details of other techniques characteristic of today’s intensified continuity.

(1) In particular Kristin’s Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis, our sections of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (written with Janet Staiger), and our Film Art: An Introduction.

Live with it! There’ll always be movie sequels. Good thing, too.

DB:

You’ve heard it before. Facing a summer packed with sequels, a journalist gets fed up. This time it’s Patrick Goldstein in the Los Angeles Times, and his lament strikes familiar chords. Sequels prove that Hollywood lacks imagination and is interested only in profits. Sequel films are boring and repetitious. They rarely match the original in quality. And when good directors sign on to do sequels, they get a big payday but they also compromise their talents.

Me, I want more original and plausible ideas. So, I expect, do you. Time to call in the Badger squad, the ensemble of email pals drawn from various generations of UW-Madison grad students and faculty. I asked them if we can’t understand sequels in a more thoughtful and sophisticated way—historically, artistically, in relation to other media. The result is another virtual roundtable, like the one on B-films held here a few months ago.

There were enough ideas for several blogs, and I’ve regretfully had to drop a whole thread devoted to comics and videogames. Maybe I’ll compile those remarks into a sequel. For now, the participants are: Stew Fyfe; Doug Gomery; Jason Mittell (of JustTV); Michael Newman (of Zigzigger and Fraktastic); Paul Ramaeker; and Jim Udden. I throw in some ideas as well.

Are all sequels in the arts automatically second-rate?

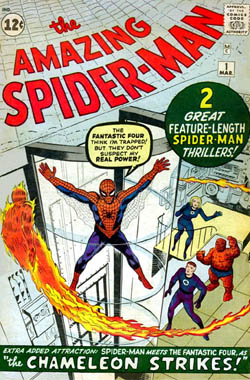

DB: The Odyssey is a sequel to the Iliad, and the second, better part of Don Quixote is a sequel to the first. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy is explicitly a followup to The Hobbit. After killing off Sherlock Holmes in “The Adventure of the Final Problem,” Conan Doyle resurrected him for more exploits. The Merry Wives of Windsor brings back Sir John Falstaff after his death in Henry IV Part II, because, supposedly, Queen Elizabeth wanted to see him again, this time in a romance plot.

Michael Newman: Sequels exist in all narrative forms–novels, plays, movies, television, videogames, comics, operas. What is the Bible but a series of sequels? Didn’t Shakespeare follow up Henry IV with a part II? What of Wagner’s Ring Cycle and Updike’s Rabbit novels? Many novelists of high reputation have written sequels, including Thackeray, Trollope, Faulkner, and Roth. There is nothing intrinsically unimaginative about continuing a story from one text to another. Because narratives draw their basic materials from life, they can always go on, just as the world goes on. Endings are always, to an extent, arbitrary. Sequels exploit the affordance of narrative to continue.

What about film sequels? What’s their track record?

DB: Goldstein grants the excellence of Godfather II, but what about Aliens, The Empire Strikes Back, Toy Story 2, and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (arguably the best entry in the franchise)? We have arthouse examples too, provided by Satyajit Ray (Aparajito and The World of Apu), Bergman (Saraband as a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage), and Truffaut (the Antoine Doinel films). If we allow avant-garde sequels, we have James Benning‘s One-Way Boogie Woogie/ 27 Years Later. As for documentaries, what about Michael Moore’s Pets or Meat?, the pendant to Roger and Me?

The world of film would be a poorer place if critics had by fiat banned all the fine Hong Kong sequels, notably those spawned by Police Story, A Better Tomorrow, Drunken Master, Once Upon a Time in China, Swordsman, and so on up to Johnnie To’s Election 2 and Andrew Lau’s Infernal Affairs 2. And arthouse fave Wong Kar-wai hasn’t been shy about making sequels.

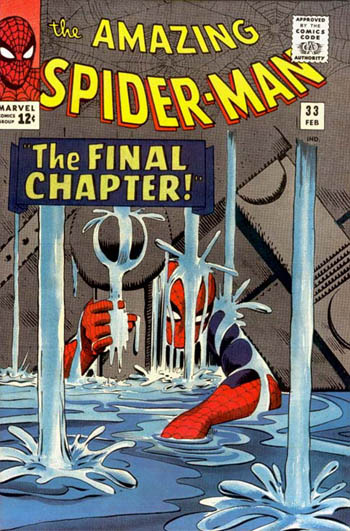

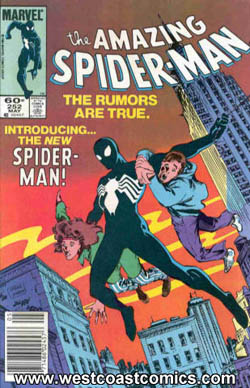

Stew Fyfe: Other sequels of quality: The Bride of Frankenstein, Mad Max II (The Road Warrior), Spider-Man 2, X-Men 2, Dawn of the Dead, Sanjuro, Quatermass and the Pit. Personally, I’d also add Blade 2, Babe 2 and The Devil’s Rejects, but I’m sure those are arguable. Would The Limey be a sequel to Poor Cow? Del Toro speaks of Pan’s Labyrinth as a companion piece or “sister-film” to The Devil’s Backbone. If you want to include docs, there’s always the Up series.

Why are there film sequels in the first place?

DB: Most film industries need to both standardize and differentiate their products. Audiences expect a new take on some familiar forms and materials. Sequels offer the possibility of recognizable repetition with controlled, sometimes intriguing, variation. This logic can be found in sequels in other media, which often respond to popular demand for the same again, but different. Remember Conan Doyle reluctantly bringing back Holmes, and Queen Elizabeth asking to see Sir John in love.

Doug Gomery: Sequels happen because the studio owners have never figured out any business model to predict success. If #1 is popular, perhaps #2 will be almost as popular. Until recently, producers seldom expected the followup’s revenues to equal the first. The basics were keep costs low, keep risks low, and make a profit. Maybe not a large as the breakthrough initial film—but at least a profit.

But they’re not a contemporary development. As part of the Hollywood studio system, they have existed in all eras—the Coming of Sound, the Classical Era, and the Lew Wasserman era. They surely seem to be surviving Wasserman as well. Indeed, as much as I admire Wasserman, who can defend Jaws 2 and its successors?

In the classic era, it may seem that there were fewer sequels as such, but there was a variant called rewrites in another genre. Years ago as I did my first book, a study of High Sierra, I watched Colorado Territory with something close to awe. It’s a gangster film turned western almost line by line. After all, Warners owned the literary rights: why not recycle it?

Given the mercenary impulse behind sequels, does a director’s willingness to make one mean that he or she has sold out?

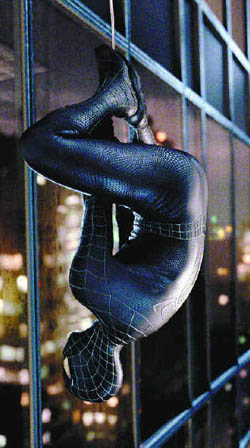

Goldstein: “Look at the great talent who’s on the sequel beat: Steven Soderbergh has done two Ocean’s sequels. Bryan Singer, the wunderkind behind The Usual Suspects, has done X-Men 2 and is at work on a sequel to Superman Returns. Christopher Nolan has left behind the raw originality of Memento to do Batman movies. Robert Rodriguez, who burst on the scene with El Mariachi, has done two sequels for Spy Kids, with a Sin City sequel on its way. After making Darkman and A Simple Plan, Sam Raimi seemed poised to be our generation’s dark prince of meaty thrillers but has turned himself into an impersonal Spider-Man ringmaster instead.”

Paul Ramaeker: To assume that the Spider-Man films must necessarily be less personal than Darkman or A Simple Plan (both of which are heavily indebted to the strictures of their genres) is to perpetuate a culturally snobbish perspective on comic books. I’ve not seen S-M3, but Raimi is a genuine fan of the character, a character with a long and complex narrative history, and given the way S-M2 continues and develops threads from the first film, I see no reason to assume he didn’t have some artistic investment in presenting his interpretation of the character over 3 films (or however many) to present a larger “story” about the character. Why should this not be seen as “personal” filmmaking to the same extent as any other kind of adaptation?

Moreover, speaking as a Soderbergh fan: I may not like Ocean’s 12 as much as Ocean’s 11, but it seems like an experiment made in good faith to me. It is a stranger movie than you would think from the way it gets picked up in articles like Goldstein’s. In fact, the way it plays with audience expectations is both dependent upon familiarity with the first film, and radically divergent from it- in many ways, it does the exact opposite of what sequels are supposed to do, which is to provide a “cozy” (Goldstein’s word) repetition of familiar pleasures. Perhaps it failed (again, I remain sort of fond of the film, which I think was best described as being like an issue of Us Weekly as put together by the editors of Cahiers du cinéma), but even so I think you’d have to call it a failed experiment rather than a rehashing.

Stew Fyfe: At a guess, I’d say that audiences or critics might evaluate the worthiness/mercenary nature of sequels by asking three questions:

(1) Has the sequel been made because there’s more story to tell?

(2) Has the sequel been made because the characters are great and people want to see them again?

(3) Has the sequel been made because there’s more money to be made?

Obviously, any combination of all three can be answered in the affirmative for any sequel and presumably the sequel wouldn’t get made if the answer to (3) was No. But with something like The Two Towers, (1) gets priority, while with Pirates 2 + 3, (3) nudges out (2). Even with (3), money, as the primary motivation, one could still make a good film. The suspicion of milking the franchise just makes the movie an easier target for critics.

Do sequels automatically equal predictability?

Jason Mittell: The line that most interests me in Goldstein’s piece is the last: “When it comes to entertainment, I’ll take excitement and unpredictability over familiarity every time.” This sets up a false dichotomy between the known and the unknown. As David and I both blogged about a few months ago, knowing a story doesn’t preclude suspense and excitement (and for some viewers, it might actually enhance it). And arguably knowing a storyworld actually allows for greater opportunities for excitement and unpredictability – a film/episode/entry in any series that doesn’t need to spend much time introducing already-established settings, characters, conflicts, etc. can literally cut to the chase. Think of the second Bourne film as a good example, or Spider-man 2 as a chance to deepen character once basic exposition is accounted for.

Paul Ramaeker: I have a theory. In the contemporary comic-book blockbuster, the sequels will always be better than the first entries. Spider-Man 2 is better than Spider-Man, X-Men 2 is better than X-Men, and I will bet that The Dark Knight will be better than Batman Begins, just as Batman Returns was better than Batman. The pattern seems to me to be that the first film in the series is relatively impersonal—the franchise must be established as a franchise, meaning that few boats will be rocked, and the director must prove that they can handle both a film on that scale, and can be trusted with the property with all the investment it represents.

But once they’ve done so, in the above cases where the first films enjoyed significant economic (and critical) success, the directors are given a bit more leeway, are allowed to drive the family car a little further and a little faster. In each case, the second film in the series by the same director has been significantly more idiosyncratic. Batman Returns has much more of Burton‘s sense of humor and interest in the grotesque; X-Men 2 is a much more serious and ambitious film narratively and thematically, more obviously the product of a prestige filmmaker (Singer’s never been an auteur by any stretch, so that will have to do). Spider-Man seemed sort of anonymous in terms of style, but Spider-Man 2 had a much more extensive and playful use of classic Raimi techniques: short, fast zooms; canted angles; rapid camera movements; whimsical motivations for techniques, like the mechanical-tentacle POV shot (virtually a repeat of his flying-eyeball POV from Evil Dead 2).

Who knows what The Dark Knight will be like, but I’m prepared to put money on the claim that it will have something to do with how people construct elaborate narratives around themselves to explain, justify, or obscure their actions and motives.

Are sequels part of a larger trend toward serial narrative?

DB: We can continue a story in another text within the same medium, but we can also spread the storyline across many platforms—novels, films, comic books, videogames. Henry Jenkins has called this process transmedia storytelling.

Michael Newman: Compared with literary fiction, there seems to be a strong propensity toward the never-ending story in genre storytelling like sci-fi and fantasy and superhero comics and spy novels and soap operas. Much of the cinematic sequel storytelling today might be considered as this kind of serialized genre storytelling. Such serials tend to have a low aesthetic reputation in comparison to more respectable genres. (The cinematic comparison would be summer blockbusters vs. fall Oscar bait.) Serial forms have historically been associated with children (e.g., comic books) and women (e.g., soaps). In other words, there is cultural distinction, a system of social hierarchy, at play.

Stew Fyfe: Yes, the longer-standing comics universes have made regular use of serial continuity to forge after-the-fact connections. It’s a form of what fans call retcon or “retroactive continuity.”

Sci-fi writer Phillip Jose Farmer used a similar concept, the “Wold Newton family” to link various mystery, pulp, crime, sci fi, adventure and spy fiction characters (so that Sherlock Holmes, Doc Savage, Sam Spade, The Shadow, Captain Blood and James Bond, among others, all become linked). Alan Moore did something similar with The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and Warren Ellis in Planetary. More limited filmic examples of this might be Zatoichi vs. Yojimbo, or Enemy of the State (which more or less sticks The Conversation‘s Harry Caul into a Bruckheimer film). There’s Freddy vs. Jason, which very adroitly observes and incorporates the continuities of two long-standing, mostly dormant franchises. In television, there’s that whole, rather insane St. Elsewhere continuity thing.

In the current crop of movie sequels featuring superheroes, one thing that has been noticeable is the casting of minor characters who might serve as springboards for later storylines. We’ve seen Dylan Baker play Dr. Connors in two Spidey films, for example, so if they decide to go with The Lizard as a villain in one of the later films, they’ve already set him within the film series’ continuity. Aaron Eckhart’s casting as Harvey Dent in The Dark Knight could similarly be used to set up Two Face as a villain for film 3.

This is similar to the idea of leaving a film “open for a sequel,” but it seems more closely integrated into the planning and execution of the film. It also points to a middle ground between the “We’re going into this making three unified films” model (Lord of the Rings) and the “We can make more money, so let’s see what plot elements we can build off of” (Pirates of the Caribbean). This is more of a “We’re probably going to make more films, let’s give ourselves something to work with” model.

It also raises the question, I guess, if you want to start speaking of dangling causes extending past the end of a film, or in the case of Pirates, the conversion of plot elements into something like dangling causes. In Pirates 1, we hear of Bootstrap Bill Turner getting chained to a cannonball and shot out into the ocean, but wasn’t it after he was made immortal by the curse of the Aztec gold? I guess you could call this a retroactive cause. Or, noting the similarity to “retcon,” a “retcause.” Never mind, that sounds lame.

Michael Newman: In the contemporary era of media convergence, serialized storytelling is becoming a mainstay across media and genres. Serial narratives supposedly facilitate spreading franchises out across multiple platforms. The media franchise demands long-format storytelling that can be spun off in multiple iterations. The rise of sequels is a much larger issue than a bunch of directors trying to make lots of money or audiences having unadventurous tastes–sequel/serial franchises are a central business model in the media industry today, supported and encouraged by the structure of conglomeration and horizontal integration.

The real point of the LAT article is that Hollywood is all commerce and no art, and sequels are a symptom. But this is such old news. And to connect it to a Squeeze summer tour is really stretching.

Jason Mittell: I think Michael’s cross-media point is crucial – continuity of a narrative world is a core part of nearly every storytelling form, but the language of “sequel” is applied predominantly to film. “Series” seems a more respectable term, as it suggests an organic continuity rather than a reactive stance of “Hey, let’s do that again!”

Are some serial/ sequel forms better suited to different media?

Jason Mittell: I think the LAT article is ultimately trying to valorize cinema’s potential to introduce something new, in reaction to the presumed rise of legitimate and praised series narratives on television (The Sopranos, Six Feet Under, Lost, etc.). And perhaps he has a point. Maybe film should stick to presenting compelling stand-alone short stories, since television has emerged as the leader in narrating persistent worlds? Or maybe I’m just saying that to pick a fight…

Jim Udden: I disagree that films should stick with one-off feature-length productions and leave ongoing series work to TV. Television has long had its Made for TV Movies, so why shouldn’t cinema think more in terms of series than it does? After all, if these are truly hard times for the film industry, as we’re always told, doesn’t it make more economic sense to adapt, just as TV has done in the last couple of decades?

True, there are things that cannot be matched on either side. I cannot imagine any film ever matching the daunting complexity of Deadwood or The Wire. Then again, some things work best as a stand-alone concern. Try to imagine a sequel to Pan’s Labyrinth or Children of Men, or try to imagine either film being made only for TV, for that matter. Moreover, some sequels should never be made. (Remember 2010?) On the other hand, some films would have been better off had they been pitched as an HBO series. (Syriana comes to mind.)

Yet film has proven its ability to take on a series format even when it is not called that. In a sense the oeuvres of most of the great art cinema auteurs are series of sorts. Aren’t Tati’s films a series with the ongoing presence of Hulot (or Hulots, if we include the false ones in Play Time)? And does anybody castigate Wong Kar-wai for following up Chungking Express with Fallen Angels, or In the Mood for Love with 2046, which are not series, but mere (gasp!) sequels? Clearly these examples were based not just on aesthetic visions, but on banking on previous success. Why do we give them a pass, but not more mainstream fare?

I think the more closely we look, the more we might find there are series and sequels even if they are not tagged by those names. It does happen in documentary, and not just in the 7 Up series. For example, American Dream does seem to me to a continuation of Harlan County USA, if not an outright sequel. Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11 combined make for a more complex argument about the relation of the defense industry to class issues than each one does on its own.

In other words, none of these formats has any value on its own. Everything depends on the type of stories to be told and the talent and economic wherewithal to find the best format for that story (or argument). The most appropriate format could be just a two-hour film, or it could be a television series going on for years. Or it could be something in between, such as the first two Infernal Affairs films, which got clumsily condensed into one film in The Departed. Both television and film can equally participate in such in-between formats.

DB: I don’t agree with all of these arguments and opinions, and I don’t expect you to either. The point is that compared to journalists’ rote dismissal of sequels, these writers offer more stimulating and more probing arguments. These guys are researchers and teachers, and they offer detailed evidence for their claim. They also write clearly, a point to remember when people say that film academics always talk in jargon and pontificate about gaseous theories.

To end on an upbeat note, I note that some journalists avoid the conventional wisdom. Consider Manohla Dargis’ recent and welcome defense of the blockbuster. Her case doesn’t seem to me spanking new: the artistic possibilities of the format have been defended for several years by film historians, as well in Tom Shone’s lively 2004 book Blockbuster. (1) Still, in the pages of the good, gray Times, Dargis’s piece remains something of a breakthrough. Maybe some day the paper will host a defense of sequels as well. If so, consider this communal blog a prequel.

(1) A sample, with Shone responding to the charge that the ’70s blockbuster drove out ambitious American filmmaking: “Any revolution that left it difficult for Robert Redford to make a movie as self-importantly glum as Ordinary People can be no bad thing” (Blockbuster, 312).

PS 30 June: Jason Mittell continues the conversation by contesting another journo’s claim that the public is tiring of sequels this summer.

Kia ora from New Zealand

KT here:

David and I have been fairly busy during our first week and a half as Hood Fellows at the University of Auckland. Our hosts have kindly scheduled all our talks for early on in our stay, leaving time to see the attractions of Auckland and its surroundings.

This past Sunday we took a tour of some of the Waitomo Caves, famous primarily for caverns in which thousands of glowworms light up the ceiling like so many stars. It’s quite a long ride by bus to reach the area. This happens to be the off-season for tourists in New Zealand, May being the equivalent of the Northern Hemisphere’s November. So far, however, we’ve actually experienced a streak of unseasonably warm, sunny weather.

We happened to be the only passengers on the bus going down to Waitomo, though there we joined a group totaling seven for the actual cave tour. On the way, we initially saw lots of fog and then spectacular mountains and valleys. That part of New Zealand is largely devoted to dairy farms, so we saw many bucolic landscapes full of cows.

Our driver, Pete, regaled us with many stories, including how a group of tourists had dubbed his bus (then brand new) Tillie. Pete hadn’t recognized the connection to the old Walter Matthau-Carol Burnett movie Pete ‘n’ Tillie, but he liked the name and has used it ever since.

As we neared Waitomo, Pete took us off the main route onto a more scenic road. As we drove, he pointed out Woodlyn Park, a motel with themed rooms, including two “hobbit holes.” These look fairly similar to the facades used in The Lord of the Rings, except that the two fronts are joined at the middle, like a Middle-earth duplex, or as the British say, semi-detached. The furniture inside apparently is people-sized rather than appropriate for hobbits. The photos on the motel’s website look somewhat incongruous, with their modern stove and sink, but the beautiful surroundings suggest that for a fan doing an independent driving tour through New Zealand, this would be a pleasant place to spend the night.

I had been aware of Woodlyn Park from the period when I was scanning for internet for LOTR-related products for The Frodo Franchise. I had never particularly taken note of where it was, so this unexpected chance to see it, if only from the road, seemed like a fortuitous coincidence.

In my previous entry, I mentioned that Māori TV is running a series of classic New Zealand films on Sunday nights. We got back from our Waitomo trip just in time to catch Vincent Ward’s first feature, Vigil (1984). It’s an impressive debut, with brooding images of harsh landscapes punctuated by startling cries of birds. The result looks like a blend of Bergman and Tarkovsky.

The film deals with a girl living with her parents on a struggling sheep farm and her efforts to understand the baffling events happening around her without much guidance. Her father is killed trying to retrieve a lost sheep, and her mother, embittered by her lost dreams of becoming a ballerina, tries to force her tomboy daughter to start practicing in the hope that they soon can leave the farm behind. Into all this wanders a vaguely threatening poacher who may or may not have illicit designs on the heroine.

Told largely from the girl’s point of view, the result is a grim but fascinating study in character and mood. It’s a pity that Vigil is not currently available on DVD, though used copies with various region codings are knocking around the internet.

By the way, I managed to see Ward’s most recent film, River Queen (above), at the American Film Market in 2005. Apart from in New Zealand, the film has had virtually no distribution, apparently going direct to DVD in some countries. (It’s currently available from German Amazon and on pre-order status at French Amazon.)

Again, it’s a pity, because although it’s not a masterpiece, it’s an entertaining and engaging period adventure involving a woman who goes into the New Zealand wilderness to rescue her kidnapped son. It is done on an epic scale that deserve to be seen on the big screen. Rumors of various problems that plagued and prolonged the filming have given River Queen an undeservedly bad reputation. Apart from a bit of choppy exposition at the beginning, I saw few signs of the fact that Ward had not been able to finish all the planned footage.

Samantha Morton’s illness (and rumored clashes with Ward) delayed the film, but she gives an intense and convincing performance. So does Cliff Curtis, an excellent Māori actor (The Piano, Once Were Warriors, and Whale Rider) who has also turned into an all-purpose ethnic player, cropping up in a wide variety of roles—often Arabs—in such films as Three Kings, The Insider, and the current Sunshine.

I also mentioned that Jane and the Dragon, a children’s television series co-produced by Weta Workshop, was premiering here on May 19. Upon further research, I discovered that the series played in Canada and Australia way back in October of 2005. It premiered on September 9, 2006, on NBC in the US. (I don’t follow children’s television, so I had missed watching it then.)

The series is one of several in the Qubo agreement, whereby NBC and other companies pledge to promote quality children’s television. Perhaps this constitutes an admission that that’s not what we’ve been getting up to now.

The first episode of Jane and the Dragon was charming, though it definitely was aimed at small children. The original book has been reissued as a tie-in to the series, and the Amazon description lists it as suitable for ages 4 to 8.

For me the series’ main interest lies in the innovative technique Weta Workshop has developed to aid in the CGI. When I first interviewed Richard Taylor, head of the Workshop, back in October, 2003, he emphasized that his company depended very little on digital technology. In contrast, the other half of Weta Ltd., Weta Digital, is entirely computer-based, providing the cutting-edge CGI not only for The Lord of the Rings but also King Kong and sequences in I, Robot, X-Men 3: The Last Stand, Eregon and others. By our second discussion, in December, 2004, Weta Workshop was moving more toward digital technology. A new motion-capture studio was just beginning to be tested. No doubt the Workshop’s designers will continue to emphasize real props, maquettes, prosthetics, and similar objects, but it has branched out.

The result in Jane is a world that resembles a series of detailed colored-pencil illustrations from a children’s book. The world is three-dimensional, however, with the characters created in sophisticated motion capture and the “camera” gliding freely through the “drawn” space. The effect is a little disconcerting at first, with the characters in lively motion and the backgrounds utterly still. Once one gets used to the contrast, however, the effect is pleasant and technically very impressive. Despite the use of motion capture, the characters are stylized rather than realistic, like detailed cel animation but in 3D.

Tomorrow I am scheduled to take the ominously named “Mordor & Mt. Doom Express.” This is a lengthy drive out from Auckland to the area around Mt. Ruhapehu, where Frodo and Sam struggled up the mountain to destroy the Ring (when they were not doing the same thing against blue and green screens in the studio). The point is not just to visit the movie locations from The Lord of the Rings, though. Naturally the filmmakers chose some of the most dramatic scenery in the country to embody Middle-earth—places a tourist would want to visit quite apart from their appearance in the movie.

Then on Sunday I’m headed for a brief stay in Wellington, where I spent many exciting weeks doing the interviews and facilities tours that constituted much of the research for The Frodo Franchise. I hope to be able to report from there in my next entry.

Glowworms show up as tiny green lights. They spin single strands that hang below them and catch small insects drawn into the cave by air currents.