[insert your favorite Bourne pun here]

Thursday | August 30, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

You may be tired of hearing about The Bourne Ultimatum, but the world isn’t.

It’s leading in the international market ($52 million as of 29 August) and has yet to open in thirty territories. It’s expected, as per this Variety story, to surpass the overseas total of $112 for the previous installment, The Bourne Supremacy. According to boxofficemojo.com, worldwide theatrical grosses for the trilogy are at $721 million and counting. Add in DVD and other ancillaries, and we have what’s likely to be a $2-$3 billion franchise.

There’s every reason to believe that the success of the series, plus the critical buzz surrounding the third installment, will encourage others to imitate Paul Greengrass’s run-and-gun style. In an earlier blog, I tried to show that despite Greengrass’s claims and those of critics:

(1) The style isn’t original or unique. It’s a familiar approach to filmmaking on display in many theatrical releases and in plenty of television. The run-and-gun look is one option within today’s dominant Hollywood style, intensified continuity.

(2) The style achieves its effect through particular techniques, chiefly camerawork, editing, and sound.

(3) The style isn’t best justified as being a reflection of Jason Bourne’s momentary mental states (desperation, panic) or his longer-term mental state (amnesia).

(4) In this case the style achieves a visceral impact, but at the cost of coherence and spatial orientation. It may also serve to hide plot holes and make preposterous stunts seem less so.

I got so many emails and Web responses, both pro and con, that I began to worry. Did I do Ultimatum an injustice? So I decided to look into things a little more. I rewatched The Bourne Identity, directed by Doug Liman, and Greengrass’s The Bourne Supremacy on DVD and rewatched Ultimatum in my local multiplex. My opinions have remained unchanged, but that’s not a good reason to write this followup. I found that looking at all three films together taught me new things and let me nuance some earlier ideas. What follows is the result.

For the record: I never said that I got dizzy or nauseated. The blog entry did, however, try to speculate on why Greengrass’s choices made some viewers feel queasy. Some of those unfortunates registered their experiences at Roger Ebert’s site. For further info, check Jim Emerson’s update on one guy who became an unwilling receptacle.

Another disclaimer: For any movie, I prefer to sit close to the screen. In many theatres, that means the front row, but in today’s multiplexes sitting in the front row forces me to tip back my head for 134 minutes. So then I prefer the third or fourth row, center. From such vantages I’ve watched recent shakycam classics like Breaking the Waves and Dogville, as well as lesser-known handheld items like Julie Delpy’s Looking for Jimmy. My first viewing of Ultimatum was from the fifth row, my second from the third. (1)

Finally: There are spoilers ahead, pertaining to all three films.

How original?

Someone who didn’t like the films would claim that they’re almost comically clichéd. We get titles announcing “Moscow, Russia” and “Paris, France.” You can poke fun at lines of dialogue like “What connects the dots?” and “You better get yourself a good lawyer” and the old standby “What are you doing here?” But these are easy to forgive. Good films can have clunky dialogue, and you don’t expect Oscar Wilde backchat in an action movie.

More significantly, all three films are quite conventionally plotted. We have our old friend the amnesiac hero who must search for his identity. Neatly, the word bourne means a goal or destination. It also means a boundary, such as the line between two fields of crops–just as our hero is caught between everyday civil law and the extralegal machinery of espionage.

The film’s plot consists of a series of steps in the hero’s quest. Each major chunk yields a clue, usually a physical token, that leads to the next step. Add in blocking figures to create delays, a hierarchy of villains (from swarthy and unshaven snipers to jowly, white-haired bureaucrats), a few helpers (principally Nicky and Pam), and a string of deadlines, and you have the ingredients of each film. (Elsewhere on this site I talk about action plotting.) The last two entries in the series are pretty dour pictures as well; the loss of Franka Potente eliminates the occasional light touch that enlivened Bourne Identity right up to her nifty final line

All three films rely on crosscutting Bourne’s quest with the CIA’s efforts to find him, usually just one step behind. Within that structure most scenes feature stalking, pursuits, and fights. In the context of film history, this reliance on crosscutting and chases is a very old strategy, going back to the 1910s; it yields one of the most venerable pleasures of cinematic storytelling.

Mixed into the films is another long-standing device, the protagonist plagued by a nagging suppressed memory. Developing in tandem with the external action, the fragmentary flashbacks tease us and him until at a climactic moment we learn the source: in Supremacy, Bourne’s murder of a Russian couple; in Ultimatum, his first kill and his recognition of how he came to be an assassin. The device of gradually filling in the central trauma goes back to film noir, I think, and provides the central mysteries in Hitchcock’s Spellbound and Marnie.

By suggesting that the films are conventional, I don’t mean to insult them. I agree with David Koepp, screenwriter of Jurassic Park and Carlito’s Way, who remarks:

There are rules and expectations of each genre, which is nice because you can go in and consciously meet them, or upend them, and we like it either way. Upend our expectations and we love it—though it’s harder—or meet them and we’re cool with it because that’s all we really wanted that night at the movies anyway. (2)

There can be genuine fun in seeing the conventions replayed once more.

The series makes some original use of recurring motifs, the most obvious being water. The first shot of the first film shows Jason floating underwater; in the second film he bids farewell to the drowned Marie underwater; and in the last shot of no. 3, we see him submerged in the East River, closing the loop, as if the entire series were ready to start again. There’s also a weird parallel-universe moment when Pam tells Jason his real name and birthdate. She does it in 2, and then, as if she hasn’t done it before, tells him again in 3, in what seem to be exactly the same words. In 3, though, it has a fresh significance as a coded message, and a new corps of CIA staff is listening in, so probably the second occurrence is a deliberate harking-back. Or maybe Bourne’s amnesia has set in again. [Note of 9 Sept: Oops! Something that’s going on here is more interesting than I thought. See this later entry.]

The look of the movies

The big arguments about Ultimatum center on visual style. The filmmakers and some critics, notably Anne Thompson, have presented the style as a breakthrough. But again, the movie is more traditional than it might first appear.

In a film of physical action, the audience needs to be firmly oriented to the space and the people present. The usual tactic is to present transitional shots showing people entering or leaving the arena of action. What might be filler material in a comedy or drama—characters driving up, getting out of their vehicles, striding along the pavement, entering the building—is necessary groundwork in an action sequence. So we see Bourne arriving on the scene, then his adversaries arriving and deploying themselves, in the alternation pattern typical of crosscutting. Surprisingly, for all the claims made about the originality of Greengrass’s style in 2 and 3, he is careful to follow tradition and give us lots of shots of people coming and going, setting up the arena of confrontation.

Then the director’s job is just beginning. Traditionally, once the scene gets going, the positions and movement of the figures in the action arena should be clearly maintained. Likewise, it’s considered sturdy craftsmanship to delineate the overall space of the scene and quietly prepare the audience for key areas—possible exits, hiding places, relations among landmarks. (See this entry for how one modern director primes spaces in an action scene.) I claimed in the earlier entry that such basic orienting tasks aren’t handled cogently in Ultimatum, and a second viewing of the scene in Waterloo Station and the chase across the Tangier rooftops hasn’t made me change that opinion. Later I’ll discuss how Greengrass and some commentators have defended the loss of orientation in such scenes.

All the films in the trilogy employ traditional strategies of setting up the action sequences, but the series displays an interesting stylistic progression. In Identity, Liman gives us mostly stable framings and reserves handheld bits for moments of tension and point-of-view shots. He saves his fastest cutting for fights and chases.

Supremacy displays a more mixed style. It contains passages of wobbly, decentered framing, but those exist alongside more traditionally shot scenes—stable framing, with smooth lateral dollying and standard establishing shots. There are some aggressive cuts, as in the crisp emphasis on the sniper at the start of the first pursuit, but on the whole the editing isn’t more jarring than usual these days. We also get, as I mentioned in the earlier entry, some almost willfully obscure over-the-shoulder shots, and occasionally we get the eye-in-the-corner technique that would become more prominent in Ultimatum.

As we’d expect, in Supremacy the bounciest camerawork and choppiest editing are found in the sequences of the most energetic physical action. Most of the surveillance scenes get a little bumpy, while the chases are wilder. The most extreme instance, I think, is the very last chase in the tunnel, when Bourne avenges the death of Marie and slams the sniper’s vehicle into an abutment. As in Identity, Supremacy arrays its technique along a continuum, saving the most visceral techniques for the most brusing action sequences.

So Ultimatum raises the stakes by applying the run-and-gun style more in a more thoroughgoing way. Everything is dialed up a notch. The flashbacks are more expressionistic than those of Supremacy: instead of dark hallucinations we get blinding, bleached-out glimpses of torture and execution, in staggered and smeared stop-frames. The conversation scenes are bumpier and more disjointed; the cat-and-mouse trailings are more disorienting, with jerky zooms and distracted framings; the full-bore action scenes are even more elliptical and defocused. It’s as if the visual texture of Supremacy’s tunnel chase has become the touchstone for the whole movie.

That texture I tried to describe in the earlier entry. Greengrass relies on camerawork, cutting, and sound to convey the visceral impact of action, rather than showing the action itself. The most idiosyncratic choices include framing that drifts away from the subject of the shot, oddly offcenter compositions, and a rate of cutting that masks rather than reveals the overall arc of the action. Some critics have liked the film’s technique, some have hated it, but I think my account stands as a fair account of the destabilizing tactics on the screen, and a likely source of some spectators’ vertigo.

Run-and-gun, with a gun

The style of Ultimatum is a version of what filmmakers call run-and-gun: shot-snatching in a pseudo-documentary manner. This approach has a long history in American film. The bumpy handheld camera, I tried to show in The Way Hollywood Tells It, has been repeatedly rediscovered, and every time it’s declared brand new. I have to admit I’m startled that critics, who probably have seen Body and Soul, A Hard Day’s Night, The War Game, Seven Days in May, or Medium Cool, continue to hail it as an innovation. Today it’s a standard resource for fictional filmmaking, to be used well or badly.

What’s at issue here are the role it plays and the effects it achieves. In Lars von Trier’s The Idiots, I’d argue that handheld work becomes genuinely disorienting because the camera is scanning the scene spontaneously to grab what emerges. But von Trier’s roaming camera yields rather long takes compared to what we find in the Bourne series. Greengrass is practicing what I called, in Film Art and The Way Hollywood Tells It, intensified continuity.

This approach breaks down a scene so that each shot yields one, fairly straightforward piece of information. The hero arrives at the station. Car pulls up; cut to him getting out; cut to him walking in. Traditional rules of continuity—matching screen direction, eyelines, overall positions in the set—are still obeyed, but the dialogue or physical action tends to be pulverized into dozens of shots, each one telling us one simple thing, or simply reiterating what a previous shot has shown. (Oddly, sometimes intensified continuity seems more, rather than less, redundant than traditional continuity cutting.)

Within the intensified continuity approach, we can find considerable variation. I argued that one highly mannered version can be found in Tony Scott’s later work, where the shots are fragmented to near-illegibility and treated as decorative bits. You can find Scott’s signature look tawdry and overwrought, but Liman and Greengrass belong in the same tradition. All three directors rely on telephoto lenses, for example, and they have recourse to well-proven techniques for rendering hallucinatory states of mind, as in these multiple-exposure shots, one from Man on Fire and the second from Bourne Supremacy.

Despite the stylistic differences among the three Bourne films, the basic one-point-per-shot premises remain in place. Here’s a passage from Supremacy. Jason gets off the train in Moscow. We get an establishing shot of the station as the train pulls in, followed by a shot of him getting off, moving left to right. The establishing shot is a smooth craning movement down, but the following shot is a little shaky.

Then we get a blurry shot of him walking, taken with a very long lens. A head-on shot like this traditionally creates a transition allowing the filmmaker to cross the axis of action, letting Jason walk right to left in the next shot.

Cut to closer view: Jason turns his head slightly. Cut to what he sees, in a shaky pov: Cops.

The answering handheld shot shows Jason reacting. As he strides on purposefully, a still closer shot accentuates his eye movement and adds a beat of tension.

Jason turns and goes to the pay phones, followed by the unsteadicam, then turns his head watchfully. A smooth match-on-action cut brings us closer.

But then Jason turns back to his task, and suddenly a passerby blots out the frame.

When the frame clears, a jouncy shot shows Jason’s hands thumbing a phone book. This might be a continuation of the same shot, or the result of a hidden cut. I suggest in The Way Hollywood Tells It that such stratagems are common in intensified continuity: blotting out the frame, flashing strobe lights, and other devices can create a pulsating rhythm akin to that of cutting. Jason turns the pages, and a jump cut shows him on another page.

Cut back to him scanning the pages. He writes down an address, in a very shaky framing.

Cut back again to Jason, and another smooth match-on action brings us back to the slightly fuller framing we’ve seen already. Greengrass shoots with at least two cameras simultaneously, which can facilitate match-cutting like this.

Jason strides toward us, going out of focus. Then a stable long shot pans with him, moving left as before. He leaves the station.

A very simple piece of action has been broken into many shots, some of them restating what we’ve already seen. In the days of classic studio filming, most directors wouldn’t have given us so many shots of Bourne leaving the train platform; a single tracking shot would have done the trick. A single shot could have shown us Jason at the phone, scribbling down the address. As a result, the whole passage is cut faster than in the classic era. The sequence lasts only forty-one seconds but shows sixteen shots. Two to three seconds per shot is a common overall average for an action picture today. The rapid cutting helps create that bustle that Hollywood values in all its genres.

It’s clear, I think, that here the run-and-gun technique is laid over the premises of intensified continuity, letting each shot isolate a bit of narrative information to make sure we understand, even at the risk of reiterating some bits. Jason has arrived in Moscow, he has to be careful because cops are everywhere, now he needs an address, he finds it, he’s writing it down . . . . All of this action is bookended by long shots that pointedly show us the character arriving at the station and leaving it.

I suggested in the earlier entry that in Ultimatum, Greengrass takes more risks than in the previous film. He still assigns one piece of information per shot, but now that piece is sometimes not in focus, or slips out of the center of the frame, or is glimpsed in a brief close-up. The September issue of American Cinematographer, which arrived as I was completing this entry, explains that he encouraged his camera operators to follow their own instincts about focus and composition. (3) Seeing Ultimatum again, I realized that the film can get away with this sideswiping technique by virtue of certain conventions of genre and style.

A telltale clue, like the charred label left over from a car bomb, can be given a fleeting close-up because physical tokens are carrying us from scene to scene throughout the film and we’re on the lookout for them. A sniper racing away out of focus in the distance is a character we’ve seen before, and he’s spotted in frame center before he dodges away. The larger patterning of shots relies on crosscutting or point-of-view alternation (Jason looks/ what he sees/ Jason reacts), and so the framing of any shot can be a little less emphatic. Given intensified continuity’s emphasis on tight close-ups for dialogue, faces can be framed a little loosely, trusting us to pick up on what matters most—changes in facial expression.

In short, because there’s only one thing to see, and it’s rather simple, and it’s the sort of thing we’ve seen before in other films and in this film, it can be whisked past us. This tactic crops up from time to time in Liman’s first installment, when a shot seems to fumble for a moment before surrendering the key piece of data. For example, Jason is striding through the hotel and a wobbly point-of-view shot brings the hotel’s evacuation map only partly into view.

Again, Greengrass takes a visual device that was used occasionally in Identity and extends it through an entire film.

Realism, another word for artifice

Finally, what’s the purpose behind Ultimatum’s thoroughgoing exploitation of run-and-gun? I quoted Greengrass’s claim that it conveys Bourne’s mental states, and some critics have rung variations on this. Of course the cutting is choppy and the framing is uncertain. The guy’s constantly scanning his environment, hypersensitive to tiny stimuli. Besides, he’s lost his memory! Yet the same treatment is applied to scenes in which Bourne isn’t present—notably the scenes in CIA offices. Is Nicky constantly alert? Is Pam suffering from amnesia?

Alternatively, this style is said to be more immersive, putting us in Bourne’s immediate situation. This is a puzzling claim because cinema has done this very successfully for many years, through editing and shot scale and camera movement. Don’t Rear Window and the Odessa Steps sequence in Potemkin and the great racetrack scene in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan thrust us squarely into the space and demand that we follow developing action as a side-participant? I think that defenders need to show more concretely how Greengrass’s technique is “immersive” in some sense that other approaches are not. My guess is that that defense will go back to the handheld camera, distractive framing, and choppy cutting . . . all of which do yield visceral impact. But why should we think that they yield greater immersion?

I think we get a clue by recalling that Supremacy and Ultimatum display the run-and-gun strategy that Greengrass employed in Bloody Sunday and United 93. This approach implies something like this: If several camera operators had been present for these historic events, this is something like the way it would have been recorded. We get a reality reconstructed as if it were recorded by movie cameras. I say cameras because we’re telling a story and need to change our angles constantly; a scene couldn’t approximate a record of the event as experienced by a single participant or eyewitness. In movies, the camera is almost always ubiquitous.

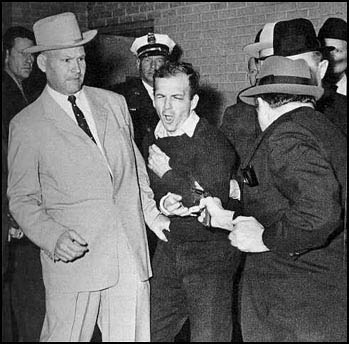

Recall the famous TV footage of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald. There the lone camera lost some of the most important information by being caught in the crowd’s confusion and swinging wildly away from the action. But in a fiction film, we can’t be permitted to miss key information. So with run-and-gun, the filmmakers in effect cover the action through a troupe of invisible, highly mobile camera operators. That’s to say, another brand of artifice.

In general, the run-and-gun look says, I’m realer than what you normally see. In the DVD supplement to Supremacy, “Keeping It Real,” the producers claimed that they hired Greengrass because they wanted a “documentary feel” for Bourne’s second outing. Greengrass in turn affirms that he wanted to shoot it “like a live event.” And he justifies it, as directors have been justifying camera flourishes and fast cutting for fifty years, as yielding “energy. When you get it, you get magic.” (4)

I’d say that the style achieves visceral disorientation pretty effectively, but some claims for it are exaggerated. So far Greengrass has matched the style to hospitable genres, either historical drama or fast-paced espionage. But isn’t immersion something we should try for in all genres? Wouldn’t High School Musical 2 gain energy and magic if it were shot run-and-gun? If a director tried that, some critics might say that it added intensity and realism, and suggest that it puts us in the minds and hearts of those peppy kids in a way that nothing else could.

I finish this overlong post by invoking Andrew Davis, director of The Fugitive (which back in 1993 gave us fragmentary flashbacks à la Bourne Ultimatum) and the admirable Holes.

When you think about the beginnings: everything was very formal and staged and composed, and then years later people said, “We want it shaky and out of focus and have some kind of honest energy to it.” And then it became a phony energy, because it was like commercials, where they would make everything have a documentary feel when they were selling perfume, you know? (5)

Whether you agree with me or not, I’m glad that The Bourne Ultimatum raised issues of film style that audiences really care about. I’m eager to look more closely at the movie when the DVD is released, but don’t worry–I don’t expect to mount another epic blog entry.However, I do have an item coming up that talks about how we assess what filmmakers say about their movies….

(1) I’m aware that this can be an uncomfortable option, but not as bad as with music. Many years ago I sat in the front row of a John Zorn concert, and I don’t think my ears ever recovered.

(2) Quoted in Rob Feld, “Q & A with David Koepp,” in Josh Friedman and David Koepp, War of the Worlds: The Shooting Script (New York: Newmarket Press, 2005), 136-137.)

(3) See Jon Silberg, “Bourne Again,” American Cinematographer (September 2007), 34-35, available here.

(4) Oddly, though, in the DVD supplement to The Bourne Identity, Frank Oz says that Liman brought “a rough-edged, very energetic” feel to the project, thanks to his indie roots. Interestingly, the energy is attributed to Liman’s abilities as a camera operator, a skill that enables him to shoot things quickly. The same supplement offers a familiar motivation for the film’s purportedly jittery style: the hero is trying to figure out who he is, and so is the viewer. Just as the films revamp a basic plot structure each time, perhaps the producers’ rationales get recycled too.

(5) Quoted in The Director’s Cut: Picturing Hollywood in the 21st Century, ed. Stephan Littger (NY: Continuum, 2006), 96.

PS: On a wholly unrelated subject Kristin answers a question on Roger Ebert’s Movie Answer Man column: What was the first movie?

PPS 5 January 2008: Steven Spielberg weighs in on the Bourne style here, confirming that he’s a more traditional filmmaker. Thanks to Fred Holliday and Brad Schauer for calling my attention to his remarks.