Archive for August 2007

Bergman, Antonioni, and the stubborn stylists

DB here:

Jonathan Rosenbaum has created quite a stir. His New York Times Op-Ed piece, “Scenes from an Overrated Career,” offers a fairly harsh judgment on the films of Ingmar Bergman. In one sense the timing was awkward; the poor man had just died. But the article wouldn’t have attracted much attention if Rosenbaum had waited a few months, so if creating a cause célèbre was his goal, he chose the right moment.

Timing aside, there wasn’t much in the piece that hasn’t been said by certain cadres of cinephiles for decades. Back in the 1960s, people called Bergman “theatrical,” “uncinematic,” pretentious, and intellectually shallow. He was even accused of hypocrisy. His spiritual, philosophical films always seemed to depend on a surprising number of couplings, killings, rapes, and gorgeous ladies, often naked. Rosenbaum contrasts Bergman with Bresson and Dreyer, more austere religious filmmakers as well as great formal innovators, and this gambit too is familiar from late-night film-society disputes. Jonathan’s case is news in the good, grey Times, but it’s an old story among his (my) generation.

I think that this generational antipathy has many sources. While Bergman had considerable academic cachet, this may have hurt him with smart-alecks like us. Cinephile priests and professors told us that Bergman was a great mind, but we suspected them of snobbery, for they often disdained even foreign filmmakers who dabbled in popular genres. Kurosawa was admired for Rashomon and I Live in Fear rather than for Seven Samurai and Yojimbo. And many of Bergman’s intellectual fans despised the classic tradition of American studio film. Hitchcock had not yet convinced literature profs of his excellence, and Ford was a gnarled geezer who made Westerns. Bergman and his acolytes seemed just too square. Our money was on Godard, especially after Susan Sontag’s magisterial essay on him.

Furthermore, some critics were on our side. Pauline Kael, with her nose for elitism, mocked ambitious European experiments like Marienbad. Andrew Sarris, who had a huge influence on our generation, initially registered respect for the arthouse kings. They proved that an artist could put a personal vision on film, thus buttressing the auteur approach to criticism. But Sarris retreated fairly fast. He was more unflaggingly enthusiastic about American popular cinema, and by contrast he often characterized the new Europeans as gloomy, middlebrow, and narcissistic. (He did, after all, coin the phrase “Antonionennui.”) Sarris made it possible for us to argue that, say, Meet Me in St. Louis was a better film than L’Eclisse or Winter Light. (1)

Of course I’m generalizing; no Boomer’s experience was identical with any other’s. Speaking just for myself, I didn’t have a deep love for Bergman, and I still don’t. I was drawn to his early idylls (Monika, Summer Interlude) and impressed but chilled by the official classics (Smiles of a Summer Night, The Seventh Seal, The Virgin Spring). Persona, I admit, was a punch in the face. Seeing it in its New York opening, I felt that all of modern cinema was condensed into a mere eighty minutes. But no Bergman film afterward measured up to that for me, and after The Serpent’s Egg I just lost interest, catching up with Cries and Whispers, Scenes from a Marriage, Fanny and Alexander, and a very few others over the later decades.

We can talk tastes forever. Maybe you think Bergman is great, or the greatest, or obscenely overrated. I think that there’s something more general and intriguing going on beyond our tastes. What makes this hard to see is that the venues of popular journalism don’t allow us to explore some of the ideas and questions raised by our value judgments.

Critical semaphore

Take some of Rosenbaum’s criticisms, which Roger Ebert has persuasively answered. I’d add that Jonathan is sometimes applying criteria to Bergman that he wouldn’t apply to directors he admires. Bergman isn’t taught frequently in film courses? So what? Neither is Straub/Huillet or Rivette or Bela Tarr. Bergman is theatrical? So too are Rivette and Dreyer, both of whom Rosenbaum has written about sympathetically.

More importantly, Jonathan’s critique is so glancing and elliptical that we can scarcely judge it as right or wrong. A few instances:

*Bergman’s movies aren’t “filmic expressions.” There’s no opportunity in an Op-Ed piece for Jonathan to explain what his conception of filmic expression is. Is he reviving the old idea of cinematic specificity—a kind of essence of cinema that good movies manifest? As opposed to theatrical cinema? I’ve argued elsewhere on this site that we should probably be pluralistic about all the possibilities of the medium.

*Bergman was reluctant to challenge “conventional film-going habits.” Why is that bad? Why is challenging them good? No time to explain, must move on….

*Bergman didn’t follow Dreyer in experimenting with space, or Bresson in experimenting with performance. Not more than .0001 % of Times readers have the faintest idea what Jonathan is talking about here. He would need to explain what he takes to be Dreyer’s experiments with space and Bresson’s experiments with performance.

In his reply to Roger Ebert, Jonathan has kindly referenced a book of mine, where I make the case that Dreyer experimented with cinematic space (and time). Right: I wrote a book. It takes a book to make such a case. It would take a book to explain and back up in an intellectually satisfying way the charges that Jonathan makes.

Popular journalism doesn’t allow you to cite sources, counterpose arguments, develop subtle cases. No time! No space! No room for specialized explanations that might mystify ordinary readers! So when the critic proposes a controversial idea, he has to be brief, blunt, and absolute. If pressed, and still under the pressure of time and column inches, he will wave us toward other writers, appeal to intuition and authority, say that a broadside is really just aimed to get us thinking and talking. But what have we gained by sprays of soundbites? Provocations are always welcome, but if they really aim to change our thinking, somebody has to work them through.

I’ve suggested elsewhere that too much film writing, on paper and on the Net, favors opinion over information and ideas. Opinions, which can be stated in a clever turn of phrase, suit the constraints of publication. Amassing facts and exploring ideas in a responsible way—making distinctions, checking counterexamples, anticipating objections, nuancing broad statements—takes more time. Academics are sometimes mocked for their show-all-your-work tendencies, and I grant that this can be tedious. But we’re just trying to get it right, and that can’t be done quickly.

Now you know why our blog entries are so damn long.

This one is no exception.

Too often film talk slides from being film comment to film chat to film chatter. Even our best critics, among whom Rosenbaum must be counted, make use of a kind of rapid semaphore, signaling to the already converted. Evidently his ideal reader agrees that good cinema is challenging and experimental, directing actresses is a minor talent, and being admired by upscale Manhattanites is a sign of a sellout. Readers will self-select; those who have congruent tastes will pick up the signals. But these beliefs aren’t really knowledge. They’re just, when you get right down to it, attitudes.

I’ll try to explore just one of the issues Jonathan raises but can’t pursue: the question of how stylistically innovative Bergman was. Of course, I can’t write a book here either. I offer what follows as simply the start of what could be an interesting research project.

One stylistic arc

The rise of European arthouse auteurs in film culture of the 1950s and 1960s put the question of personal style on the agenda, but back then we didn’t have many tools for analyzing stylistic differences among directors. We didn’t know much about the local histories of those imported films; as Sarris recently pointed out, L’Avventura was Antonioni’s sixth feature but was his first film released in the US. Moreover, we didn’t know much about the norms of ordinary commercial filmmaking, in the US or elsewhere. (2) Today we’re in a better position to characterize what went on. (3)

In most countries, quality cinema of the late 1940s relied on variations of the Hollywood approach to staging, shooting, and cutting that had emerged in the silent era. Directors moved their performers around the set fairly fluidly and used editing to enlarge and stress aspects of the action. You can see a straightforward example of this approach on an earlier entry on this blogsite.

Many directors of the period built upon this default by creating deep space in staging and framing. Using wide-angle lenses, directors could allow actors to come quite close to the camera, sometimes with their heads looming in the foreground, while other figures could be placed far in the distance. Several planes of action could be more or less in focus. Here’s a straightforward example from William Wyler’s The Little Foxes.

We find directors exploiting this approach not only in the United States but in Eastern and Western Europe, Scandinavia, the Soviet Union, Japan, Mexico, and South America. Here’s an instance from the French film Justice est faite (1950).

Why did this approach emerge in so many countries at the same time? We don’t really know. It wasn’t simply the influence of Citizen Kane, as we might think. The Stalinist cinema had developed deep-space shooting in the 1930s, and we can find it elsewhere. Probably Hollywood’s 1940s films helped spread the style, but there are likely to be local causes in various countries too.

In any event, during the 1950s two technological changes posed problems for this style. One was the greater use of color filming, which renders depth of field much more difficult. The other innovation was anamorphic widescreen, a technology seen in CinemaScope and Panavision. These systems also had trouble maintaining focus in many planes when the foreground was close to the camera. The flagrant depth compositions we find in black-and-white ‘flat’ films were quite difficult to replicate in color and anamorphic widescreen.

Through the 1960s, the deep-focus style became a minor option and directors found other alternatives to presenting character interactions. The most basic one was simply to station the camera at a middle distance and create a more porous and open staging, with fewer planes of action and simple panning movements to follow characters.

One new approach relied not on wide-angle lenses but on lenses of long focal length. Instead of staging scenes in depth, putting the camera close to a foreground figure, filmmakers began keeping the camera back a fair distance and using long lenses to enlarge the action. This accompanied a trend toward greater location shooting; it’s easier to follow actors on a street or highway if the camera shoots with a telephoto lens. The long lens also reduces the volumes of each plane, so that figures tend to look like cutouts (4). This lens facilitated the development of those perpendicular images I’ve called, in some writing and on this blog, planimetric shots.

What fascinates me about this general pattern of stylistic change in the US is how many of the Euro auteurs go along with it. Take Fellini, who shifts from the bold depth compositions of I Vitelloni to the fresco-like flatness of Satyricon.

![]()

Likewise, Luchino Visconti’s early black-and-white work affords textbook examples of deep-focus cinematography, but in the 1960s he embraced the telephoto look, heightened by what we can call the pan-and-zoom tactic. In Death in Venice, the camera often scans a scene, searching out one player to follow then zooming back to reframe the figure in relation to others. One shot starts with the boy Tadzio, pans right across the hotel salon, to end on von Aschenbach, staring at the boy, and then zooming back to take in the larger scene.

Probably Rossellini’s 1960s films, such as Viva l’Italia! and Rise to Power of Louis XIV, were key influences on this look.

Leaving Europe, there’s Kurosawa, who was the first major director I know of to build zoom and telephoto lenses into his style. Satayajit Ray followed much the same trajectory from the Apu trilogy’s flamboyant depth to the pan-and-zoom close-ups of The Home and the World. Not every filmmaker took the long-lens option, but as it became commonplace in the 1960s, many major directors tried it.

What about Bergman? It seems that in most respects he went along with the general trends. We find deeply piled-up bodies early in his career (e.g., Port of Call, below) and through the 1950s and early 1960s (The Face, below).

Like his peers, with color and widescreen he shifted toward more open staging, long lenses, and zooms. For example, one telephoto shot of Cries and Whispers zooms back as the little girl emerges, zig-zagging, from behind the lace curtain.

We might conclude that Bergman mostly worked with the received forms of his day. At the level of shot design, The Face might have been shot by the Sidney Lumet of Fail-Safe. But Bergman did innovate somewhat, I think. Most obviously, he sometimes had recourse to the suffocating frontal close-up, as in a childbirth scene from Brink of Life.

He develops this visual idea by creating heads floating unanchored in both foreground and background. Here’s a famous image from Persona.

Pace Rosenbaum, I’d say that this sequence, with Elisabeth Vogler apparently quite oblivious to her husband’s mating with Alma, definitely “challenges conventional film-going habits”—or at least conventional ways we read a scene. It seems to combine the deep-space, big-foreground scheme of the 1940s with the tight close-ups of Bergman’s early work, and instead of specifying space it undermines it. We have to ask if what happens in the background is Elisabeth’s hallucination.

My case is very schematic, and we would need to study Bergman film by film and scene by scene to confirm that he stuck to the broad norms of his time. The norms themselves also deserve deeper probing than I’ve given them. (5)

But let’s push a bit further and examine Antonioni, that perpetual foil to Bergman. Broadly speaking, he passed through the same arc, from deep-focus compositions in the 1950s and early 1960s to telephoto flatness in his color work. Yet there are some important differences.

In the 1950s, unlike Bergman, Antonioni employed quite intricate staging, sustained by long takes. He usually didn’t opt for big foregrounds, favoring more distant framings and sidelong camera movements. The most famous instance is the startling 360-degree long take on the bridge in his first feature, Story of a Love Affair, but Le Amiche is also full of intricate staging in mid-ground depth. One scene shows fashion models bustling around after a successful show, congratulating the shop’s owner Clelia. She opens a card from her lover, is distracted by the arrival of her friends coming to congratulate her, and goes off with them. One model darts diagonally forward to investigate the message. All of this is handled in a single graceful take.

Antonioni relies on the fluid staging techniques developed in the early sound era and taken in diverse directions by Renoir, Ophuls, Preminger, Mizoguchi, and other directors of the 1930s and 1940s. Often, however, Antonioni’s characters move rather slowly and hold themselves in place, and as a result the overall spatial dynamic unfolds in marked phases. (6)

In the trilogy starting with L’Avventura, Antonioni relies on shorter takes and less florid camera movement. Now he emphasizes landscape and architecture so as to diminish the characters. If the expressionist side of Bergman plays up the psychological implications of the drama, the more austere Antonioni plays things down, “dedramatizing” his scenes by keeping the camera back, turning the figures away from us, and reminding us of the milieu. (You see the Antonioni influence on similar strategies in the work of Edward Yang, as I discussed recently on this blog.)

Once color came along, Antonioni changed his style, moving toward less dense staging and at times almost casual framing (as in The Passenger). He also had recourse to the telephoto technique, but I’d argue he brought something new to it. With Red Desert he accepted the abstraction inherent in the long lens and combined that with color design to create a pure pictorialism.

Ironically, Red Desert may have made Antonioni another sort of ‘expressionist’ than Bergman. The stylized palette of the film encourages us to ask if the industrial landscape is really so smeared and bleached out, or if we’re seeing it as Giuliana does. The same sort of painterly abstraction can be found in Zabriskie Point. In one scene, a pan over the travel decals on a family’s car window treats the boy inside as no more than another thin slice of space. Other scenes turn campus policemen into figures in grids.

You might even argue that the pan-and-zoom style gets a kind of meta-treatment in the climactic shot of The Passenger. There in a grandiose technical gesture Antonioni’s concern for architecture, his refusal to underscore a melodramatic plot twist, and his love of camera movement blend with the technology of the zoom. At the time, several of us (maybe Jonathan too) saw this shot as a response to Michael Snow’s Wavelength, relayed through the sensibility of Passenger screenwriter and avant-garde filmmaker Peter Wollen. Now it looks to me like a natural response of a very self-conscious artist to a stylistic trend of the moment.

A bestiary of stylists

To get crude and peremptory: Let’s say that once a director has reached maturity and become a confident artisan, several choices offer themselves. The filmmaker can be a flexible stylist, a stubborn stylist, or a polystylist (sorry for the awkward term).

A flexible stylist adapts to reigning norms. Bergman could be an aggressive-deep-focus director, then a pan-and-zoom director. Both approaches to staging and shooting preserved the expressive dimensions that mattered most to him: performance (chiefly face and voice), Ibsenesque bourgeois tragedy, Strindbergian play with dream and dissolution of the ego, and other elements.

Most of the major 1960s arthouse directors, from Truffaut and Wajda to Pasolini and Demy, were flexible stylists in this sense. So were a great many Hollywood and Japanese directors, such as Lubitsch and Kinoshita. Perhaps Ousmane Sembene, who also died recently, would be another instance. Buñuel becomes a fascinating case: He adopts the blandest, calmest version of each trend, creating a neutral technique, the better to shock us with what he shows.

A stubborn stylist pursues a signature style across the vagaries of fashion and technology. Dreyer from Vampyr onward does this; I argue in the book Jonathan cites that he seeks to “theatricalize” cinema in a way that goes beyond the norms of his moment. Perhaps Hitchcock and von Sternberg (at least in the 1920s and 1930s) fit in here as well. Bresson, Tati, and supremely Ozu were stubborn stylists. Give them a western or a porno to shoot, and they’d handle each the same way. (7)

This isn’t to argue that stubborn stylists never change or always do the same thing. Mizoguchi has a signature style and yet remains fairly pluralistic, at least at a scene-by-scene level. I think that the test comes in seeing how stubborn stylists persistently explore the constrained conditions they’ve set for themselves.

Signature styles help a filmmaker in the festival market, so we don’t lack for current examples of stubborn creators: Godard, Theo Angelopoulos, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Kitano Takeshi, Tsai Ming-liang, and Jia Zhang-ke. Granted, some of these may be rethinking their commitment to their stylistic premises.

A polystylist tries out different styles without much concern for what the reigning norms demand. Polystylistics holds a high place in modernist aesthetics. After the great triumvirate of Picasso, Joyce, and Stravinsky, with their bewildering arrays of periods and pastiches, the idea of the modernist as a virtuoso steeped in several styles became a powerful option. What’s been called postmodernism is no less favorable to polystylism; if you mix styles, you’ve presumably mastered them.

In cinema, some polystylists are just eclectic. Steven Soderbergh can give us the portentous pictorialism of The Underneath or Solaris, the grab-and-go look of Traffic, and the trim polish of Ocean’s 11. More deeply, there are directors like R. W. Fassbinder, Raoul Ruiz, and Oshima Nagisa who seem to pursue polystylistics on principle. It’s as if, rejecting the very idea of a signature style, they set themselves fresh, severe conditions for each project.

After The Boss of It All, we may want to count von Trier as a polystylist, not merely a director who changed his style from one phase of his career to another. Perhaps the best current example is Aleksandr Sokurov; who would dare predict what his next film will look like?

This whole entry is pretty sketchy, I grant you. The categories need further refining. I’ve ignored sound, which is very important. I’ve emphasized visual style, and just shooting and staging within that. (Nothing about lighting, cutting, etc.) So this is tentative—notes perhaps for a book-length argument. But I’ve made my point if you see that some ideas and some historical information can put intuitions about originality into a firmer framework.

And I’ve left the value judgments suspended. If you think originality trumps other criteria, then Bergman doesn’t probably come up as strong as Antonioni, let alone Bresson or Ozu or Dreyer. But if you can entertain the possibility that a great filmmaker can accept certain norms of his time, making those serve other channels of expression, then Bergman can’t automatically be faulted. At least thinking about him and his peers in the context of the history of film art gives us some data to ground our arguments. The world is more interesting and unpredictable than our opinions, especially those we formulated forty years ago.

(1) I actually hold this opinion.

(2) I assume that the arthouse auteurs were no less commercial filmmakers than their Hollywood counterparts. They were sustained by national film industries and supported by the international film trade. Eventually many were funded by Hollywood companies.

My friend and colleague Tino Balio is at work on a book tracing the role of overseas imports in the American film market of the 1940s-1960s, and it should be a real eye-opener to those who persist in counterposing art cinema and commercial production.

(3) Some of what follows is discussed in Part Four of Film History: An Introduction.

(4) I talk about both the deep-focus and long-lens tendencies in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style and Chapter 5 of Figures Traced in Light.

(5) For a wide-ranging account of art-cinema norms, see András Bálint Kovács’ forthcoming book, Screening Modernism: European Art Cinema, 1950-1980.

(6) I analyze this tendency, using other scenes from Le Amiche, in On the History of Film Style (pp. 235-236) and Figures Traced in Light (pp. 151-152).

(7) Suo Masayuki’s My Brother’s Wife: The Crazy Family is a softcore film made in a pastiche of Ozu’s style.

Story of a Love Affair (Cronaca di un amore).

PS, Sunday 12 August: Only a day later, new thoughts about something else I should have said about generational tastes. In the light of the Woody Allen eulogy that appears in the New York Times today, I think there’s more of a sub-generational split than I’d initially suspected. So here’s another gesture toward the sort of history of taste that Jonathan mentions.

Allen is in his seventies, a decade older than Jonathan Rosenbaum and me. He came of age in the affluent decade after the war. Allen saw Bergman films in the mid- to late 1950s, probably against the backdrop of Neorealism, British comedy, and French Cinema of Quality. In that context, Bergman’s movies looked pretty revolutionary.

But Jonathan and I came to maturity, if that’s the right word, in the mid-1960s. When I got to college in 1965, French directors (notably Resnais, Godard, Truffaut) and the Czechs, Hungarians, and others were getting established in US film culture. Bergman, Fellini, and Antonioni were already senior directors and soon they were starting to make what many of us perceived as career mistakes (Juliet of the Spirits, The Passion of Anna, even Blow-Up). Also, of course, concerns about their political alignments came more to the fore as the decade wore on. Many of my friends thought that The Battle of Algiers left all other films in the shade. These factors may have made the Boomers suspicious of “arty” foreign imports, of which Bergman’s work was a central instance. Interestingly, The Dove, a parody of The Seventh Seal and a film-society staple, came out in 1968, when Bergman may have been wearing out his welcome.

[Speaking of parodies, the SCTV skit, “Scenes from an Idiot’s Marriage”, in which Jerry Lewis (Martin Short) suffers the indignities of a cuckolded Bergman hero, is well worth checking out. The SCTV Fellini/ Antonioni parody, “Rome Italian Style,” is also pretty good, especially for its excellently awkward dubbing.]

Interestingly, Scorsese in age falls midway between Allen and us Boomers, and he contributes a Times tribute to Antonioni today. Maybe I have to split the generations even more: Bergman for 1955-1960, Antonioni for 1961-1965, Godard for 1965-1970? (Just kidding.) What strikes me are the differences in the essays. While Allen ranges widely, reports conversations, and praises Bergman in general terms, Scorsese’s piece evokes the texture of L’Avventura, suggesting how disturbing and demanding it was to watch. Maybe he inadvertently backs Jonathan’s claim that Bergman didn’t challenge his audience as much as he might have?

I’m grateful as well to readers responding to my arguments. Michael Kerpan kindly spread the word about my post on imdb and the Criterion Forum. Kent Jones wrote to point out that any argument about Bergman’s influence has to take into account the high regard in which he’s been held in France, among both critics and filmmakers. Kent itemizes not only Godard, Truffaut, and Rivette but Assayas, Téchiné, and Desplechin. It’s a fair point. Antoine de Baecque anchors much of his magisterial history of Cahiers du Cinéma around the mesmerizing power of that busty still of Harriet Anderson, flaunted on a 1958 Cahiers cover and swiped by Antoine in The 400 Blows. In 2003, my old friend Jacques Aumont published a large critical study on Bergman. Cahiers’ next issue will be devoted to the director.

I’m grateful as well to readers responding to my arguments. Michael Kerpan kindly spread the word about my post on imdb and the Criterion Forum. Kent Jones wrote to point out that any argument about Bergman’s influence has to take into account the high regard in which he’s been held in France, among both critics and filmmakers. Kent itemizes not only Godard, Truffaut, and Rivette but Assayas, Téchiné, and Desplechin. It’s a fair point. Antoine de Baecque anchors much of his magisterial history of Cahiers du Cinéma around the mesmerizing power of that busty still of Harriet Anderson, flaunted on a 1958 Cahiers cover and swiped by Antoine in The 400 Blows. In 2003, my old friend Jacques Aumont published a large critical study on Bergman. Cahiers’ next issue will be devoted to the director.

Speaking of French critics and directors, on imdb above Bertrand Tavernier points out that my memory failed. I did see Scenes from a Marriage and Cries and Whispers before The Serpent’s Egg, not after, as my post suggests.

My late Bergman viewing remains gappy. I still haven’t seen the long version of Fanny and Alexander, which everyone assures me is a masterpiece. Last spring, my friend and Bergman scholar Paisley Livingston showed me portions of the TV film The Last Gasp (1995). It’s about Georg af Klercker, the fine Swedish director of the 1910s. It was intriguing, but I was put off by Bergman’s inadequate pastiches of af Klercker’s remarkably poised and complex shots. Now that’s fussy taste, I admit.

Gandalf speaks! More thoughts-and news-on the Hobbit project

Local hero: Peter Jackson portrayed in toast, Wellington Airport, July 2004

Kristin here—

While the new “Frodo Franchise” website is under construction, I offer here a new set of speculations on the Hobbit project.

In my July 20 entry, I cited a statement by Ian McKellen concerning possible progress in the ongoing legal dispute between Peter Jackson and New Line Cinema. The dispute is the reason given by the studio’s president, Bob Shaye, for Jackson’s not being asked to direct the film adaptation of The Hobbit. There Sir Ian said, “I detect that there is movement and it’s movement in the right direction.” That interview went online July 19.

The Royal Shakespeare Company’s tour then moved on to Australia, and on July 26 an Australian Broadcasting Corporation television interview with McKellen brought up the question again. Here the response is somewhat more specific:

KERRY O’BRIEN: What’s happening with The Hobbit?

SIR IAN MCKELLEN: I talked to one of the Hollywood producers who is in a position to know, who said there seemed to be a little bit of movement and he is a circumspect man so I took that to mean something quite positive and I’ll be seeing Peter Jackson in a couple of weeks when we’re taking The Seagull to Wellington and Auckland.

KERRY O’BRIEN: It would be tragic if it happened without Peter Jackson?

SIR IAN MCKELLEN: It couldn’t happen really, could it? In the way that it ought.

McKellen is currently playing King Lear and, in repertoire, Sorin in The Seagull. The schedule began at Stratford on 24 March and by November will have visited Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Singapore, Melbourne, Wellington, Auckland, New York, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, and London. Currently he is in Wellington, where the engagement that he mentions, including both King Lear and The Seagull, runs August 11 to 13.

This new interview seems to add a little to the one in Singapore that I quoted previously. I don’t want to read too much into McKellen’s statement. Still, I can infer (as usual with the proviso that I have no inside information) a couple of things.

In Singapore, McKellen referred to “detecting” movement in the Hobbit front, but he doesn’t hint as to his source. Here he says he heard this from a producer. Perhaps such a communication would involve said producer sounding him out about the circumstances under which he would be willing to reprise his role as Gandalf. McKellen has made it clear on his website and in interviews, including this new one, that he feels Jackson should direct and has strongly implied that he would not play the wizard under a different director. He has not, however, made a firm public statement to that effect. The fact that in this context he mentions meeting with Jackson, however, suggests that he may have some reason to believe that they could work together on the film.

(Subsequent interviews with McKellen have been published in Australia and New Zealand, but none adds any new information.)

I had the pleasure of interviewing McKellen in early 2005 as part of my research on The Frodo Franchise. He made it perfectly clear that he, like virtually all the cast and crew members that worked on The Lord of the Rings, is intensely loyal to Jackson. I would be very surprised to hear that he had agreed to play Gandalf if someone other than Jackson were at the helm.

Second, these two interviews, one done in Singapore and one in Melbourne, were posted on the internet a week apart. There is no hint that anyone asked McKellen not to say anything more about the Hobbit negotiations. Given the intense interest in this subject, even brief, very general statements like the ones I have quoted can give rise to considerable speculation and discussion—in which I am obviously participating.

As anyone who has read interviews with McKellen knows, he is a very outspoken man. Still, I can’t believe that he would go on making statements about the situation with the Hobbit film if asked not to by the parties involved.

Now I’d like to turn to an issue unrelated to the McKellen interview. One subject that comes up in fan discussions of the Hobbit project on the internet is that of design. Fans point out that if Weta Ltd. does not create the props, costumes, sets, special effects (both digital and physical) and make-up, as they did for The Lord of the Rings, the look of Middle-earth might be noticeably different. Other fans seem to believe that Jackson’s companies own the props, costumes, and sets.

Technically I believe that New Line owns virtually all of the objects made for Rings. Some were given as gifts to the filmmakers, including the full-size Bag End interior which Jackson now has at his country home as a guest house. Some of the actors received their swords, McKellen asked for and got the lizard-shaped door-handles from the Orthanc set, and so on. That’s not a major factor, and the existing objects, which are presumably still in storage in New Zealand, could be re-used for a film of The Hobbit.

Nevertheless, design and execution would remain a big concern. If Weta’s two halves, Weta Digital and Weta Workshop, refused to work on The Hobbit without Jackson directing, New Line and co-producer MGM would have to look elsewhere. (Jackson owns one third of Weta, and the other two-thirds are owned by his long-time friends and colleagues Richard Taylor and Jamie Selkirk.) There are a few CGI facilities in the world that could deliver digital effects on the level of those in Rings—though it’s hard to imagine a Gollum without Andy Serkis’ acting, particularly his voice. But I doubt that there is any company or cluster of companies that could render the physical components of Middle-earth as well as Weta Workshop did for Rings. Tolkien illustrators Alan Lee and John Howe helped give the film’s mise en scene its unified look, and they, too, might not wish to work for a different director.

This is all speculation, and time might prove me to have been completely wrong. Perhaps New Line could successfully assemble a fully new team—director, cast, crew and group of support companies—and start virtually from scratch. Perhaps there is not the solidarity behind Jackson that I have posited here, and some people who worked on Rings might be willing to return for The Hobbit under such circumstances. Perhaps fan opposition would gradually erode once the film went into production.

Unlikely as it may seem now, there was a storm of outrage when Jackson was first announced as directing Rings. Most people had never heard of him. People who knew his comic splatter films were convinced that he would trash Tolkien’s novel. Perhaps a new director could win fans over, as Jackson did so effectively, and make them change their opinions. I have to believe, though, that any new director would face a much harder uphill battle to capture the fans’ hearts and minds.

A recent poll on TheOneRing.net asked whether fans would be likely to go to a film directed by anyone but Jackson. The group saying that they were “very likely” and “likely” not to go was 76.6 %. Those who were “very likely” and “likely” to go totaled 12.9%. Those who said they would wait until they found out who the director would be comprised 10.3%. Many among that 76.6% group would probably grit their teeth and go to the film.

Perhaps the result would be a hit and we shall look back upon the current period as a tempest in a teapot. If so, perhaps the lawsuit will eventually come to court and we’ll get some indications as to the real cost of this dispute.

By the way, Keith Stern, McKellen’s webmaster, has kindly put The Frodo Franchise on the news page of McKellen.com, right next to the announcement of Sir Ian’s nomination for an Emmy for his hilarious guest turn on the British series Extras. I seldom get a chance to think of myself as cool, but that is definitely cool!

IMPORTANT NEWS: Just after posting this entry, I discovered (via the excellent site The Hobbit Movie) a Los Angeles Times story on New Line Cinema. There studio officials finally announce that they are indeed negotiating with Peter Jackson concerning the Hobbit film project:

“Eager to move ahead with ‘The Hobbit,’ New Line has quietly been trying to mend fences with ‘Rings’ filmmaker Peter Jackson, who has sued the company over his share of profits from the first ‘Rings’ films. When asked if it was true that company insiders had been in talks with Jackson’s reps, Shaye replied, “Yes, that’s a fair statement. Notwishstanding our personal quarrels, I really respect and admire Peter and would love for him to be creatively involved in some way in ‘The Hobbit.'”

“Moving ahead with ‘The Hobbit’ would tie in to another pivotal New Line issue: In an era when Hollywood is deluged with equity money, will Shaye and Lynne make a run at buying back New Line from Time Warner? Shaye’s reponse was worthy of a U. N. diplomat: ‘We have not expressed that point of view publicly. And if we ever do, [Time Warner chiefs Dick Parsons and Jeff would be the first to know about it.'”

I don’t know why the Hobbit film is tied to that issue, but it presumably has something to do with the fact that investors would be falling over themselves to help finance such a project. The Lord of the Rings may have strengthened New Line enough that it would be better off being once again a fully independent firm–as it was before being acquired by Turner Broadcasting System in 1993. (TBS was in turn acquired by Time Warner in 1996.)

This announcement confirms that my most general speculation in past entries is correct: New Line has been negotiating with Jackson. Whether the proposition is for Jackson to produce and direct or simply to produce (“creatively involved in some way”) remains to be seen.

[Added on August 10:

In response to the LA Times story, Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh have issued a statement: “Peter and Fran have always wanted to do The Hobbit but whether that happens is yet to be decided.”]

Updates: Len Lye, Frodo Franchise, blockbusters, and news from/about Hong Kong

Kristin here—

More on Len Lye

After my recent post on Len Lye, I heard from both Roger Horrocks, Lye’s biographer, and Tyler Cann, Curator of the Len Lye Collecton of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth, New Zealand. (Neither with corrections, I am happy to say!) They have filled me in on some activities that should make Lye’s film work more accessible.

First, a DVD of Lye’s films is being prepared. Unfortunately factors like the process of assembling the best surviving prints means that the finished product will not be available in the near future.

Second, the near future will bring a touring program of Lye’s films to North America. Called “Free Radical: The Films of Len Lye,” it has been organized by The New Zealand Film Archive, the Len Lye Foundation, and Anthology Film Archives. (The name was inspired by Lye’s scratched-on-film animated short, Free Radicals, 1958.) Here are the venues and dates:

Oct 12 Anthology Film Archives, New York

Oct 12 Anthology Film Archives, New York

Oct 18 NASCAD (Nova Scotia College of Art and Design) Halifax, Nova Scotia

Oct 23 Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley

Oct. 28 Film Forum, Los Angeles

Oct 30th CALARTS, Los Angeles

Nov 2nd University of Notre Dame, Indiana

Nov. 7th George Eastman House, Rochester

Nov. 26th Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge

Dec 8th Chicago Filmmakers, Chicago

Dec. 15th International House, Philadelphia

Roger tells me that he intends to write a book on Lye’s theory and practice of what he called “the art of motion.” This reminds me that I forgot to mention that there is a collection of Lye’s writings, Figures of Motion: Len Lye Selected Writings, co-published in 1984 by Auckland University Press and Oxford University Press. It was co-edited by Roger and Wystan Curnow and is, alas, long out of print. Another thing to look for in your local library.

The Frodo Franchise

I am happy to report that The Frodo Franchise is now in the process of being rolled out. The University of California Press has been shipping copies for weeks, and it should soon appear on bookstore shelves—and may have already in some places. The copy we pre-ordered from Amazon back in April arrived on July 30.

I have bowed to the inevitable and am in the process of constructing a separate website, “Frodo Franchise,” to deal with matters relating to the book and the films. (That is, Meg, our web czarina, is constructing it.) I don’t want information about the book, comments on the Hobbit film situation, and similar items to overbalance our blog, which they threaten to do. I’ll post a notice when the site is up and running.

In the meantime, Pieter Collins of the Tolkien Library, an excellent reference and news site dedicated to the novels, has interviewed me about my book. You can read the result here. Henry Jenkins has done the same, through his site, Confessions of an Aca-Fan, is more oriented toward popular media and fandom. The interview is in three parts here, here, and here.

Hollywood Blockbusters Doing Pretty Well

On February 28 I posted an entry, “World rejects Hollywood blockbusters?” There I argued against claims in an article by Nathan Gardels, editor of NPQ and Global Viewpoint, and Michael Medavoy, CEO of Phoenix Pictures and producer of, among many others, Miss Potter. They claimed that there were many signs that Hollywood’s big-budget films are being rejected at the box office: “Audience trends for American blockbusters are beginning to show a decline as well, both at home and abroad.”

Since then, of course, Hollywood blockbusters have been cleaning up at home and abroad. We’re all familiar by now with the series of huge international openings, with many blockbusters being released day and date in most major markets. As one example, take Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, which so far has grossed $774,070,000 worldwide. The US and Canada claimed only about one-third ($264 million) of that total (Box Office Mojo, August 4). Overseas, Phoenix has scored $510 million, for 65.9% of its global haul. The Three Threes, Shrek, Pirates, and Spider-man, all cleaned up internationally, as did Transformers. (The fourth Three film, The Bourne Ultimatum, looks set to do the same.) The Simpsons Movie has recently begun its climb to box-office glory.

Leonard Klady, an excellent writer on the international film industry, summed up the situation for 2007 in the 22 June print edition of Screen International: “Worldwide predictions that 2007 would break recent box-office records look to be well founded. The international box office generated $4.5bn in the first four months of 2007. Combined with revenues from the domestic North American marketplace, the global gross for the period was $7.2bn. International theatrical [i.e., markets outside the U.S. and Canada] accounted for 61.6% of the worldwide box office on gross figures that exceeded domestic ticket sales by 60.6%. Based on current viewing trends, global box office could finish the year at a record-breaking $24.6bn.”

Klady points out that much of the rise comes from the factor I discussed in my earlier entry: the expansion of the international market. According to him, “The international market has become increasingly significant in the past decade.” A decade ago, foreign income averaged 45% of Hollywood films’ takings. By 2006 it was around two-thirds.

These facts also bear on Neil Gabler’s February article, “The movie magic is gone,” where he lamented the purported decline in theatrical films’ importance. That there was such a decline, he claimed, was evidenced by the fact that box-office revenues are down, both domestically and abroad. I refuted Gabler’s claims at some length in this March 11 post, and the successful summer that Hollywood is now enjoying adds further evidence to show that his argument was based on false assumptions.

DB here–

The Udine Far East Film Festival had a tremendous program this year, and just the YouTube promo made you want to book a ticket. But I couldn’t go! Still, the organizers kindly sent me their excellent catalogue Nickelodeon and the real topper, the festival’s thick volume dedicated to Patrick Tam Kar-ming. Editor Alberto Pezzotta, indefatigable researcher into Hong Kong film, organized a vast retrospective of Tam’s key New Wave films, such as Nomad and The Sword, as well as his less-known television work. The book includes critical essays, a detailed filmography, and a long, informative interview. Tam brought a cosmopolitan sensibility to Hong Kong film, thanks to his sensitivity to European directors like Godard and Antonioni. His latest film, the widely acclaimed After This, Our Exile, signals a new phase in his career.

When I was writing Planet Hong Kong between 1997 and 1999, I was often frustrated by a lack of solid information and in-depth critical writing. Tony Rayns’ superb essays and the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival were about all I could rely on. That situation has improved in recent years, with many well-researched books on Hong Kong film appearing. Outstanding here is Stephen Teo, who has given us two books this year alone: King Hu’s A Touch of Zen and the just-out Director in Action: Johnnie To and the Hong Kong Action Film. This efflorescence of writing comes just when local cinema is in its deepest slump. You won’t find me quoting Hegel often, but in this instance it does seem that the owl of Minerva is flying at dusk.

When I was writing Planet Hong Kong between 1997 and 1999, I was often frustrated by a lack of solid information and in-depth critical writing. Tony Rayns’ superb essays and the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival were about all I could rely on. That situation has improved in recent years, with many well-researched books on Hong Kong film appearing. Outstanding here is Stephen Teo, who has given us two books this year alone: King Hu’s A Touch of Zen and the just-out Director in Action: Johnnie To and the Hong Kong Action Film. This efflorescence of writing comes just when local cinema is in its deepest slump. You won’t find me quoting Hegel often, but in this instance it does seem that the owl of Minerva is flying at dusk.

Two Chinese men of the cinema

A Brighter Summer Day.

DB here:

This summer two major figures in Chinese filmmaking died. One was Edward Yang (Yang Dechang), one of Taiwan’s finest directors, who died on 29 June. But before I pay tribute to him, I want to acknowledge another figure who had a great impact on Asian cinema.

Charles Wang died on 6 July. Along with his brother Fred, Dr. Wang ran Salon Films, the major supplier of film equipment for Hong Kong and a principal one for East Asia and the Pacific Rim. Charles graduated with a degree in chemistry before inheriting the business from his father. As Hong Kong filmmaking grew in sophistication, Salon grew along with it. Most Hong Kong films bear the firm’s brand in their end credits.

Since 1969 Salon has provided top-flight cameras, lenses, lighting gear and other technical support for both local and visiting productions, such as Mission: Impossible III‘s Shanghai shoot. An early triumph was winning the Panavision franchise for the region. The company even supplies trampolines and landing cushions for martial acrobatics, as this glimpse inside a Salon van shows.

Since 1969 Salon has provided top-flight cameras, lenses, lighting gear and other technical support for both local and visiting productions, such as Mission: Impossible III‘s Shanghai shoot. An early triumph was winning the Panavision franchise for the region. The company even supplies trampolines and landing cushions for martial acrobatics, as this glimpse inside a Salon van shows.

When I interviewed Dr. Wang in 2003 he kindly gave me information about the company and the development of film technology in Hong Kong. He showed me his many awards and talked enthusiastically about Salon’s new efforts to assist mainland moviemaking. In recent years, Salon was investing in films such as Zhang Yimou’s Hero. Like most Hong Kong film people, he was very accessible and generous; he even gave me a lift back to my hotel. Charles Wang was a major force in the Hong Kong industry and will certainly be missed.

Laconic cuts and long takes

I met Edward Yang twice. First, at a Hong Kong Film Festival reception, we chatted about his film Mahjong (1996), which had screened. I got to know him a little better in fall of 1997, when we were both invited to the Kyoto Film Festival. We ate and watched films together, and we shared baby-boomer nostalgia; it turns out that he and I (and Hou Hsiao-hsien) were all born in the same year.

I found him friendly, thoughtful, and open to appreciating all film traditions. He spoke of enjoying Japanese swordplay movies in his youth, and he admired American films for their gripping stories. Still, his preference for ellipsis and understatement came through. When we met Kitano Takeshi for dinner, Edward praised a crisp transition in Sonatine: to show the gang going from Tokyo to Okinawa, Kitano simply gives us a quick pan of the sky accompanied by the sound of a jet plane.

Yang was an accomplished cartoonist, and I thought that this background partly explained his early style, on display in the short film Desires (1982) and in the features That Day, on the Beach (1983), Taipei Story (1985), and The Terrorizers (1986). In these films Yang often breaks his scenes into simple but striking fragments. After the police shootout in The Terrorizers—one of the most enigmatic and elliptical opening sequences in modern cinema—the Eurasian girl staggers out to the street. Yang gives us her collapse in quite abstract, percussive images. Her foot hits the pavement. Cut. She takes a step and falls out of frame; the camera holds on the empty frame. Cut. She’s lying on the crosswalk. I imagine these as forceful, laconic comic-book panels.

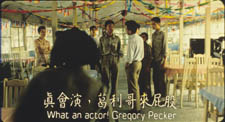

With A Brighter Summer Day (1991), my favorite of his works, Yang tells another gap-filled story but treats the scenes in long, distant, often decentered takes reminiscent of Hou. Now his frames are more dense with figures and furniture, and layers of action extend quite far back. In Figures Traced in Light, I devote a little—too little—analysis to one admirably staged passage. Another of my favorite scenes in A Brighter Summer Day shows the hero Xiao S’ir developing a romantic attachment to Ming, the girlfriend of the absent gang leader Honey. They sit in a brightly decorated café.

Suddenly Ming darts out of the shot, leaving Xiao S’ir and the other boys staring. From their point of view we see that Honey, dressed in a sailor suit, has returned and Ming has gone to meet him.

Yang cuts back to the boys as Honey’s gang starts to threaten Xiao S’ir. Abruptly, Ming runs into the shot, past the boys, down the long central aisle, and out of the café. (In a 35mm print you can see her pausing and lingering outdoors.)

The group closes around Xiao S’ir; only Honey’s entry breaks the tension. He leads the boy into the depth of the shot, the camera following them.

Honey warns Xiao S’ir off, and our hero goes outside, mimicking the path Ming had followed.

As Honey turns his attention to his gang and an upcoming skirmish with their rivals, he moves back down the aisle, the camera backing up. Once his business is done, Honey drifts back to the rear door.

Honey pauses far from us, at the window. Yang cuts to show what he sees: Xiao S’ir, in flagrant violation of the warning, talking to Ming outside.

First we got Xiao S’ir’s point of view on Honey and Ming; now, in a reversal, we get Honey’s point of view on Ming and Xiao S’ir. In scenes like this, Yang merges his developing skills in long-take staging with cuts that develop not only the action but story parallels. Very distant framings, characters moving to the rear of the shot and turning their backs: Yang “dedramatizes” the scene. Further, by shifting point of view, he leaves us guessing about story information: What led to Ming’s running away from Honey? What are Xiao S’ir and Ming talking about now? Yang created a laconic visual approach that, I’d argue, invests fairly standard dramatic situations with a tantalizing uncertainty.

Yang’s best-known film is, of course, Yi Yi (2000), and it won him the wide appreciation that he had long deserved. It’s a warm and gentle work, less innovative than his earlier efforts but utterly typical of his vision of lives pervaded by melancholy routine and abrupt disappointment. People often remarked that the adolescent hero of A Brighter Summer Day resembled Edward himself. Perhaps too in Yi Yi Yang’s enigmatic pictorialism is echoed in the idea of a little boy who makes photographs of people’s heads seen from the rear. Like the director, the boy (named Yang-yang) displays a reticence that respects the mysteries of people’s private lives.

We already have a very useful guide to Yang’s work in one chapter of Emilie Yueh-Yu Yeh and Darrell William Davis’ book, Taiwan Film Directors. And Criterion’s Curtis Tsui has done a wonderful edition of Yi Yi, as Brian Hu shows here. We must hope that Criterion, Eureka, or another gilt-edged DVD publisher will soon bring us Yang’s other works in the pristine editions they deserve.

A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

In 1998, when we screened A Brighter Summer Day at our Cinémathèque, I wrote a program note. I reproduce it, lightly revised, as a quick pointer to one of the great films of the 1990s.

With Taipei Story (1985) and The Terrorizers (1986) Edward Yang established himself as one of the two leaders of the Taiwanese New Wave generation. At first it seemed that he and Hou Hsiao-hsien had agreed to a division of labor in their subjects and styles. Hou tended to concentrate on life in the countryside, or on rural characters transplanted, bewilderingly, to the modern city. Hou was also deeply interested in the history of Taiwan; his most acclaimed film, City of Sadness (1989), is a panoramic survey of Taiwanese society immediately after World War II. Hou’s tranquil style favored a contemplative mood and muted emotion.

Yang, by contrast, tended to focus on the lives of well-to-do urbanites in a contemporary setting, Taiwanese yuppies plagued by anomie and the desperation of love and work. His elliptical editing technique, reminiscent of Resnais, fractured time and space, while his compositions had a painterly starkness. The Terrorizers shuttles kaleidoscopically among characters at its beginning; their relations only gradually settle into intelligible patterns. Whereas Hou tended toward nuance and quiet drama, Yang was unafraid of shocking, inexplicable bursts of bloodshed.

Now it seems evident that this impression of a division of labor was somewhat schematic. Hou’s range of interests has widened, with new emphasis on the violent world of urban crime (Goodbye South Goodbye, 1996), and he has come to rely on quite disorienting transitions between past and present (Good Men, Good Women, 1995). Likewise, with A Brighter Summer Day Yang turned to history and cultivated a more sober style of filming, with lengthier shots and a fixed or barely moving camera. This approach throws down a challenge to the razzle-dazzle of contemporary popular cinema—from Hollywood, Hong Kong, and even the American “independents”—and invites us to scrutinize, moment by moment, the details of action unfolding on the screen.

Three years in the making, A Brighter Summer Day was a triumph of independent production. At a period when the Taiwanese film industry was virtually dead, Yang found money (mostly Japanese) to mount a project of remarkable ambition. Over half the cast and crew had never worked on a film before. At first released in a three-hour version, the film was re-released in a four-hour director’s cut, and this has become the standard version.

The historical event examined in A Brighter Summer Day took place in Taipei in the 1960s, when an adolescent boy about Yang’s age stabbed a young woman. At epic length Yang creates a web of circumstances around the event. He shows the interplay of traditional culture—filial duty, education as an ideal of social advancement—with popular culture, especially the rock n’ roll songs that recur throughout. Yang has said that Americans might not realize the shattering force of rock in other cultures: “These songs made us think of freedom.”

The film has over eighty speaking parts, most filled by nonactors, and it intertwines several characters’ destinies. On first viewing, the film can be somewhat bewildering to a non-Taiwanese audience, so a plot sketch may help. (Skip to the next paragraph if you don’t want to know the action in advance.) At the center is fourteen-year-old Xiao Si’r. He tries to be a dutiful student, but with his friends Cat and Airplane, he lives on the fringes of the Little Park gang of teenage thugs. When Xiao Si’r reports seeing a gang member with another boy’s girlfriend, he triggers a power struggle in the gang. As his friends fall by the wayside and rival gangs fight for control of local turf, Xiao S’ir becomes involved with Ming, a girl who’s attached to Honey, exiled leader of the Little Park gang. A major climax occurs during a gang rumble at a rock n’ roll concert. Interwoven with the juvenile intrigues are political matters; the police pursue and question Xiao S’ir’s father about his Communist friends. Xiao S’ir becomes friendly with Ma, a general’s son, before they start to compete for Ming’s favor. The rivalries build to a tense schoolroom confrontation and a tragic finale in the park. In the final scene and over the credits, a radio transmission broadcasts the names of the students who have passed their school entrance exams.

The plot is even more intricate than my bare-bones summary can indicate; I haven’t discussed the boys’ adventures in a film studio or Cat’s singing career or the slender line of action involving Xiao S’ir’s sister. The breadth of action is extraordinary, and a sense of the contradictory pulls of daily life emerges steadily. No less demanding is Yang’s style—scenes played in darkness, few close-ups, with medium-shots and long-shots keeping us at a distance from the characters. But the result is a dispassionate look at teenaged passions, a deromanticized treatment of young people growing up in a repressive milieu. A Brighter Summer Day (the English title comes from Elvis Presley’s “Are You Lonesome Tonight?”) is an elegy to the ideals and mistakes of youth, an analysis of the vanities of the male ego, and a view of a generation painfully facing the limitations of tradition, the constraints of political oppression, and the demands of the modern world.

Yi Yi.