The sarcastic laments of Béla Tarr

Wednesday | September 19, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

Werckmeister Harmonies.

DB here:

Last weekend, Facets MultiMedia in Chicago held a tribute to Béla Tarr. Milos Stehlik and his colleagues have been long-time champions of Tarr’s work, holding retrospectives and releasing nearly all his features on DVD (with Sátántangó soon to come). Tarr arrived on Saturday, but an emergency sent him back to Hungary sooner than he expected. So instead of discussing his work with a panel, he could only introduce the screening of Werckmeister Harmonies before running off to the airport.

The panel went ahead, with Jonathan Rosenbaum, Scott Foundas, and me chatting with Susan Doll of Facets. It wasn’t as pungent a session as it would have been with Tarr there, but I thought it was still pretty interesting. Jonathan, Scott, and Susan had thoughtful comments, and the questions from the audience were exceptionally good. The whole session was recorded for an online broadcast at some point, so you might want to watch out for that. And I have earlier blog entries on Sátántangó here and here.

In preparation for the panel I spent last week reconsidering Tarr’s work, so I offer a few notions about his films and how we might place them in the history of cinematic form and style. Some of these remarks build on things I said at the session.

Up close and personal

Some directors accommodate critics, accepting or at least tolerating writers’ efforts to probe the work. Not Tarr. Ask about his plots and characters, and he claims that he doesn’t tell stories. Point out what seem allegorical or symbolic touches, and he protests that he doesn’t make allegories and he hates symbols. Mention contemporary cinema, and the reply is abrupt: “For me, when I see something at the cinema it is always full of shit.” And if you tell him that his early films seem quite different from his more recent ones, he vehemently disagrees.

Some directors accommodate critics, accepting or at least tolerating writers’ efforts to probe the work. Not Tarr. Ask about his plots and characters, and he claims that he doesn’t tell stories. Point out what seem allegorical or symbolic touches, and he protests that he doesn’t make allegories and he hates symbols. Mention contemporary cinema, and the reply is abrupt: “For me, when I see something at the cinema it is always full of shit.” And if you tell him that his early films seem quite different from his more recent ones, he vehemently disagrees.

As Scott pointed out in our panel, though, it can be plausible to apply the concept of “period” to filmmakers’ work as we do to painters’ careers. Lars von Trier has been fairly explicit that after mastering a polished style for his work up through Zentropa/ Europa he wanted to try something new, and with The Kingdom he shifted toward a looser, on-the-fly style that pointed toward Dogme 95. Any viewer can be forgiven for thinking that Tarr has moved in the opposite direction of von Trier, from a pseudo-documentary approach toward something much more grave and majestic.

The first three theatrical features focus on the urban working class and their struggles to improve their lot. In Family Nest (1979), a family who can’t afford a flat of their own squeezes in with the husband’s parents. The tight quarters, the ceaseless complaints of the father-in-law, and the husband’s inertia force his wife and child to flee to the streets. The Outsider (1981) follows a young violinist as he drifts among jobs and into a passive marriage before being called up for military service. The family in The Prefab People (1982) has a flat and a decent job, but the wife finds the husband indifferent to her boring routines, and he looks for an escape in a job in another town. The concentration on ordinary people’s lives and the search for drama in the everyday dissatisfactions of city life put the films in the neorealist line of succession.

Stylistically, the films are stripped down in ways that also owe debts to modern traditions. Shot mostly handheld, adjusting the framing to the actors’ performances, they belong to a strain of films from the 1960s on that sought to suggest the immediacy of cinéma-vérité documentary. Unlike many such films, however, Tarr’s buy into a long-take aesthetic. Perhaps surprisingly, these movies’ shots run abnormally long: an average shot length of 32 seconds for Family Nest, 33.5 for The Outsider, 47 seconds for Prefab People. By comparison, Hollywood films of these years were consistently running between 4 and 8 seconds per shot, and comparatively few European and Asian films rely on shots as lengthy as Tarr’s.

Most scenes in these three films are dialogues, and the camera holds intently, if shakily, on faces. This concentration is enhanced by the general absence of establishing shots. A scene opens more or less in the middle of a conversation, and we get a character already challenging another. The visual pattern is that of shot/ reverse-shot, and in most scenes the first face is counterposed to a second one by either a cut or a pan. Shooting on location in cramped rooms, Tarr makes his framings tight; in Family Nest, the jammed frames give us and the characters almost no breathing space.

By relying on more or less isolated faces in close-ups, Tarr can absorb us in the intimate drama while sometimes catching us off guard. For instance, when we get a single character without an establishing shot, there is often a momentary uncertainty about where we are, or when the action is taking place. We also can’t be sure of who’s present besides the speaker, so the close view of him or her leaves us hanging: To whom is s/he talking? We’re pushed to pay close attention to what the character is saying, looking for any clues to the dramatic context. Tarr’s tactic also delays the reaction of the listener; he may withhold sight of the conversational partner until s/he speaks. The effect, heightened by the lengthy takes, is to turn many of these scenes into monologues, in which a character pours out his or her reaction to a situation, and we’re forced to take that in more or less pure form.

By the end of Family Nest, Tarr is shooting entire scenes concentrated on a single face, and because we don’t know if there is anyone else present, we have to take the talk as virtually a soliloquy.

It’s as if Tarr invoked the stylistic schema of shot/ reverse shot and simply postponed or suppressed the reverse shot, leaving only an inexpressive shoulder in the foreground, if that. I’ve discussed the delayed reverse-shot as a convention of European cinema in an earlier blog, and Tarr makes ingenious use of it.

Tarr builds these films out of conversational blocks, punctuated by undramatic routines. The result is that often major plot actions take place offscreen, or rather in between the dialogues. Exposition that other filmmakers would give us up front is long delayed, with bits of information sprinkled through the entire film. In Family Nest, the father claims that he’s seen Iren having an affair with another man. We can’t be sure he’s lying because we haven’t strayed enough out of the household to judge her activities. In The Outsider, one scene ends with the drifter Andras telling Kata, a woman he has recently met, that he has a child by another woman. The scene ends with him smiling in indifference, leaving his sentence unfinished. In the next scene, a band strikes up a tune: Andras and Kata are celebrating their marriage.

Most filmmakers would show us more of the courtship and a scene of proposal, but Tarr moves directly to the next block, suggesting Andras’ laid-back heedlessness. Agreeing to get married is no big deal. Further, by skipping over the most obviously dramatic incidents, Tarr’s storytelling joins that tradition of ellipsis celebrated by André Bazin in his essays on neorealism. No longer does the filmmaker have to show us every link in the causal chain, and no longer are some scenes peaks and others valleys. By deleting the obviously dramatic moments, the filmmaker forces us to concentrate on more mundane preambles and consequences.

This block construction yields an unusually objective narration. These films lack voice-overs, subjective flashbacks, dreams, and other tactics of psychological penetration. We have to watch the people from the outside, appraising them by what they say and do. It is a behavioral cinema. True, Prefab People opens with a flashback: The husband is packing to leave his wife, and the plot moves back to an anniversary dinner that ends badly. But the flashback to the earlier phase of the marriage isn’t framed as the wife’s memory. When the plot’s chronology brings us back to the moment of the husband’s departure, the replay of the opening allows us to watch the characters with more knowledge of what is driving them apart. Unsurprisingly if you know Tarr’s earlier films, that replay is followed by a long monologue showing the wife expressing her sorrow at his departure, without any visual cues about who, if anyone, is listening.

Then, without preparation, we see the couple back together, shopping in an appliance store. How did they reconcile? Have their attitudes changed, or are they simply reconciled to their old life? Like Antonioni and many other modern filmmakers, Tarr doesn’t tell us such things. He simply ends his film on a long take of husband and wife riding expressionless in the back of a truck, as much pieces of cargo as the washing machine beside them.

After the Fall

The second-phase films do look and feel rather different. Almanac of Fall (1984), a story of duplicity and spite among people sponging off a well-to-do older woman, offers a wholly elegant mise-en-scene. Characters are often framed from far back, surroundings take on much more importance, the framing is stable—often with windows, doors, and furnishings impeding our view of the action—and the camera moves smoothly, often in arcs around stationary figures. The takes are even longer, averaging just under a minute. The rococo lighting (patches of color seem to follow actors around) and atmosphere of strained upper-class narcissism seem like quite a break from the working-class films. If I had to find an analogy to Almanac of Fall, it would be Fassbinder’s Chinese Roulette (1976), with its camera arabesques and slightly decadent ostentation.

The overripe shots of Almanac of Fall signaled a shift toward a self-consciously formal cinema, but then Tarr stripped his settings and cinematography down. From Damnation (1988) onward, his films feature ruined exteriors, shabby interiors, elaborate chiaroscuro, rhythmic camera movement, and very long takes. (Damnation has an ASL of 2 minutes; Sátántangó, 2 minutes 33 seconds; Werckmeister Harmonies, 3 minutes 48 seconds).

Tarr insisted in conversation with me that there isn’t a sharp break between early and late styles. For one thing, his video piece Macbeth (1982) consists of only two shots across 63 minutes. It was made before The Prefab People, so his shift toward the ambulatory long take was already in the works. Moreover, The Outsider ends with a strained restaurant encounter captured in a virtuoso handheld shot running nearly seven minutes. A nightclub scene in The Prefab People likewise features some sidewinding long takes around a dance floor that wouldn’t be out of place, at least in their repetitive geometry, in Damnation.

If we’re inclined to look for other continuities, we can find them. In the films from Damnation onward, the deferred reverse shot has been put at the service of attached point of view, so that often when Tarr’s protagonists peer around a corner or out of a window, instead of optical pov cutting we have an over-the-shoulder view that conceals their facial reaction. One scene in Damnation starts as a typically Tarrian scrutiny of texture, with the wrinkling wall echoing Karrer’s topcoat. But then the camera arcs and refocuses, showing what Karrer is watching but not how he responds.

The blocklike construction of scenes in the early films carries on in the later work, but now Tarr minimizes the cuts within a scene, so that it becomes an even more massive hunk of space and time. Tarr refuses as well to use crosscutting, which would show us various characters pursuing their activities at roughly the same time—another strategy that keeps us fastened to one relentlessly unfolding chain of actions and, usually, one character’s range of knowledge. The avoidance of crosscutting will have major structural implications in Sátántangó, which overlaps characters’ individual points of view by replaying certain events and stretches of time.

The long-held facial shots of the early films don’t create a natural arc; the shot will go on as long as the character wants to talk. Similarly, many long takes in the later films don’t present a beginning-middle-end structure. We simply follow a character walking toward or away from us, pushing into a stretch of time whose end isn’t signaled in any way. This becomes especially clear in those extended long shots in which a character walks away toward the horizon and the camera stays put. Traditionally, that signals an end to the scene, but Tarr holds the image, forcing us to watch the character shrink in the distance, until you think that you’ll be waiting forever. Likewise, the diabolical dance shots of Sátántangó, built on a wheezing accordion melody that seems to loop endlessly, are exhausting because no visual rhetoric, such as a track in or out, signals how and when they might conclude. Early and late, Tarr won’t hold out the promise of a visual climax to the shot, as Angelopoulos does; time need not have a stop.

Nonetheless, I do agree with my fellow panelists that the later films have a significantly different look and feel, and it’s on them that Tarr’s place in world film history will chiefly rest. As I indicated at the end of Figures Traced in Light, he stands out as a distinctive creator in a contemporary tradition of ensemble staging. Like Tarkovsky, he shifts our attention from human action toward the touch and smells of the physical world. Like Antonioni and Angelopoulos, he employs “dead time” and landscapes to create a palpable sense of duration and distance. Like Sokurov in Whispering Pages (1993), he takes us into an eerie, Dostoevskian realm where characters are cruel, possessed, mesmerized, humiliated, and prey to false prophets.

Ties to tradition

Tarr, however, maintains that his work, early or late, owes little to cinema. He claims not to have been influenced by other directors, and he asserts that he gets his ideas from life, not from films. When pressed, he admits that he knew the films of Miklós Jancsó “and I liked them very much. But I think what he does is absolutely different from what we do.”

It’s not uncommon for strong creators to reject the idea of influence, and many feel that they may sap their originality if they’re exposed to other work. Still, nothing comes from nothing. Any artwork is linked to others through an expanding network of affinity and obligation. Often influence is like influenza; you catch it unawares, despite your efforts to ward it off. And sometimes artists on their own find strategies that other artists have already or simultaneously hit upon.

Whether or not Tarr consciously joined a tradition, his practices do link him to several trends. Tarr has rejected the idea, floated by Jonathan, that his early films are indebted to Cassavetes, but there seems little doubt that by 1979, when Family Nest was released, it contributed to the fictional-vérité tradition, regardless of his intent. Likewise, his late films’ reliance on long takes is part of a broader tendency in European cinema after World War II. The neorealists taught us that you could make a film about a character walking through a city (The Bicycle Thieves, Germany Year Zero), and other directors, such as Resnais in the second half of Hiroshima mon Amour, developed this device. With Antonioni, Dwight Macdonald noted, “the talkies became the walkies.” Jancsó took Antonioni further (acknowledging the influence) in the endless striding and circling figures of The Round-Up, Silence and Cry, and The Red and the White. So even if there wasn’t any direct influence, Antonioni and Jancsó paved the way for Tarr; they made such walkathons as Sátántangó and Werckmeister thinkable as legitimate cinema.

Still more broadly, as Hollywood cinema has become faster-paced, accelerating its action and cutting, art cinema in Asia and Europe has tended toward ever slower rhythms. Visit any festival today, as Scott mentioned in our panel, and you’ll see plenty of films with long takes and fairly static staging. I criticize this fashion a bit in Figures, but it’s undeniably a major option on today’s menu. It’s even been picked up in contemporary American indies, with Gus Van Sant’s work from Elephant on offering prominent examples. He, of course, has been crucially influenced by Tarr, but Hou, Tsai Ming-liang, Sokurov, and other directors haven’t. We seem to have a case of stylistic convergence, with Tarr choosing to explore the long take at the same time others were doing so.

Within recent Hungarian cinema, it would be fruitful to examine Tarr’s relation to his contemporaries. Janós Szasz’s Woyzeck (1994) takes place in a wasteland not unlike those of Damnation and Sátántangó. Even closer to Tarr is the work of György Fehér. I’ve seen only Passion (1998; right) and one scene from Twilight (1990). Here again we get very long takes with a supple camera, grungy settings, and down-at-heel characters wandering in rain and mist or dancing as if possessed by demons. Fehér has worked with Tarr as producer, dialogue writer, and “consultant.” We could also explore Tarr and Fehér’s affinities with Benedek Flieghauf, the younger director of The Forest (2003) and Dealer (2004). Fleghauf builds these films around extensive long takes, and the remarkable Forest carries the idea of the suppressed reverse-shot to an eerie extreme, as characters study mysterious offscreen objects that may never be shown us.

Within recent Hungarian cinema, it would be fruitful to examine Tarr’s relation to his contemporaries. Janós Szasz’s Woyzeck (1994) takes place in a wasteland not unlike those of Damnation and Sátántangó. Even closer to Tarr is the work of György Fehér. I’ve seen only Passion (1998; right) and one scene from Twilight (1990). Here again we get very long takes with a supple camera, grungy settings, and down-at-heel characters wandering in rain and mist or dancing as if possessed by demons. Fehér has worked with Tarr as producer, dialogue writer, and “consultant.” We could also explore Tarr and Fehér’s affinities with Benedek Flieghauf, the younger director of The Forest (2003) and Dealer (2004). Fleghauf builds these films around extensive long takes, and the remarkable Forest carries the idea of the suppressed reverse-shot to an eerie extreme, as characters study mysterious offscreen objects that may never be shown us.

More generally, and more speculatively, we could look to a wider movement in late and post-Soviet art toward mournfulness and lamentation in response to cultural collapse. Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia is one instance, but Larissa Shepitko’s The Ascent (1976) and Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985) point in this direction too. Vitaly Kanevsky’s Freeze, Die, Come to Life! (1989) offers a rusting, dilapidated world not far from Tarr’s. In the 1970s and 1980s, composers like Arvo Pärt, Henryk Górecki, Giya Kancheli, Vyacheslav Artyomov, and Valentin Silvestrov created austere, threnodic music that sometimes evokes spirituality but just as often suggests a bleak end to everything. The very titles—Symphony of Sorrowful Songs (Górecki), Symphony of Elegies (Artyomov), Postludium (Silvestrov)—evoke something more than the death rattle of Communism. The pieces can be heard as meditations on the ruins of modern history, asking what humankind has accomplished and what can come next. Tarr’s severe parables, grotesque and sarcastic in the manner of Kafka, don’t exude the religiosity we can find in some of this music or filmmaking, but, at least for me, they share the impulse to lament humans’ inability to transcend their brutish ways. “I just think about the quality of human life,” he remarks, “and when I say ‘shit’ I think I’m very close to it.”

I have more ideas about Tarr, especially on Sátántangó and Werckmeister, but I have to stop somewhere. I hope to see his new film The Man from London when I go to the Vancouver International Film Festival next week, and of course I’ll report on it here.

The best piece of writing I know on Tarr’s cinema is András Bálint Kovács’ “The World According to Tarr,” in the catalogue Béla Tarr (Budapest: Filmunio, 2001).

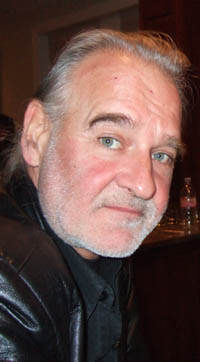

Béla mesmerizes Lola, Chicago 15 September 2007.

Thanks to Milos Stehlik, Susan Doll, Charles Coleman, and Megan Rafferty of Facets, to Béla Tarr for generous conversation, and to András Kovács for enlightening discussions over the years.

PS 20 September: The reports of Tarr’s earlier visit to Minneapolis are emerging; here’s a good link.