Archive for October 2007

Cronenberg’s violent reversals

Eastern Promises

Kristin here–

A Pair of Films

I haven’t read nearly all the review of Eastern Promises, of course. Sampling eight or so, I have noticed that quite a few critics briefly note a similarity between David Cronenberg’s new film and his previous one, A History of Violence. There are the obvious links. Viggo Mortensen plays the lead in both, a man with a secret—or a bunch of them. Both involve crime syndicates run by families. Both contain scenes of graphic, brutal violence.

Reviewer John Beifuss calls Eastern Promises “A sort of companion piece to Cronenberg’s previous feature, ‘A History of Violence’ (2005), adding that, “‘Eastern Promises’ opens in a modest barber shop that recalls the small-town diner that was the site of unexpected brutality in ‘Violence.’” Beth Accomando comments, “In some ways, Nikolai has much in common with Mortensen’s character in A History of Violence, who hides one persona beneath another.”

J. Hoberman goes a little further in defining the parallels. “Eastern Promises is very much a companion to A History of Violence. Both are crime thrillers that allow Viggo Mortensen to play a morally ambiguous and severely divided, if not schizoid, action-hero savior; both are commissioned works that permit hired-gun Cronenberg to make a genre film that is actually something else.” (For more reviews, see Rotten Tomatoes’ page on the film.)

It would be hard to discuss the similarities between the films without giving away too much of the plot, and clearly that’s why reviewers have said so little on the subject. So I should make it very clear that I’m writing a brief analysis here, not a review. There will be major spoilers for both films. I don’t always mind spoilers for films I’m going to see, but A History of Violence and especially Eastern Promises really depend on the withholding of information. I’d urge you to see both films before reading the rest of this entry.

What I’m primarily interested in here is the extent to which the second film manages to be a mirror-image reversal of the first. It’s a remarkable formal accomplishment, I think, to have a director make two consecutive films with different plots, characters, settings, and narrational strategies that are such exact reversals of each other. Eastern Promises isn’t a sequel, yet it forms a pair with A History of Violence. It’s like those trilogies that are united by theme rather than by being parts of the same story (e.g., Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, and The Silence, or Phillip Glass’s three biographical operas, Einstein on the Beach, Satyagraha, and Akhnaton). Whether or not this pairing was intended by Cronenberg, one could easily imagine him working again in the same vein.

Basically you’ve got a central character with two sides to him, the criminal and the good. In A History of Violence, the protagonist is leading an ordinary domestic life that is threatened by a revelation of his criminal past. He barely manages to suppress the threat to his family that results when his former associates re-establish contact with him, and he can suppress it only by using more violence and revealing to his family what he had been

In Eastern Promises, the hero does the opposite. He is voluntarily leading a criminal life undercover in order to fight the Russian mafia gang he works for. By meeting and falling in love with Anna, he is given a chance to lead a normal life with her but manages to suppress his longing for that in order to continue his struggle. (Even his boss in whatever crime-fighting organization he secretly works for offers him an out, saying that the Russian embassy has requested he be taken off the case. Nikolai insists on continuing his activities, since he now has had a promotion that will allow him to penetrate to the very heart of the criminal gang he has been fighting.)

There are contrasts and parallels that encourage a comparison of the two films. The modest diner that Tom Stall runs in A History of Violence could not be more unlike the  sumptuous Russian restaurant that is the front for Semyon’s vory v zakone activities. The much-lauded fight scene in the public baths in Eastern Promises is a more visceral version of a battle late in A History of Violence when Tom, about to be killed at his brother’s order, manages to kill all five of the men holding him captive. (At left, four down, one to go.)

sumptuous Russian restaurant that is the front for Semyon’s vory v zakone activities. The much-lauded fight scene in the public baths in Eastern Promises is a more visceral version of a battle late in A History of Violence when Tom, about to be killed at his brother’s order, manages to kill all five of the men holding him captive. (At left, four down, one to go.)

The black, forbidding car that Nikolai drives echoes that of the vengeful thug Fogarty in A History of Violence; both glide to ominous stops on the street outside the dwelling of their presumed victims. Each of the films ends on a close view of the protagonist seated at a table: Tom fearfully yet hopefully searching the faces of his family for signs of acceptance and Nikolai sitting in the Russian restaurant he now runs, thinking in sorrow of Tatiana and presumably of his missed life with Anna. Even the meal that Tom returns home to and the one Anna’s family are having at the end are similar: roast beef and vegetables.

Ultimately the contrasts in the two films are what makes the ending of Eastern Promises even more affecting than that of A History of Violence. Tom Stall has used deceit to walk away from his violent life and make a new and normal one. By the end the revelation of the deceit has damaged that normal life considerably, but there are indications that the damage will gradually, though not wholly, fade through re-established love and trust. Nikolai, on the other hand, has gone down the far more difficult road: walking away from a potentially normal life to continue to use deceit and violence to fight the vicious organization that preys upon normal people. (When Anna’s mother warns her away from her contact with the criminals, saying “This isn’t our world. We are ordinary people,” Stepan responds that Tatiana was an ordinary person, too.)

One thing that distinguishes the films is that we never learn whether Nikolai was already a real criminal earlier in his life, one whom the British authorities successfully recruited to help them run an underground operation against the vory v zakone in London. Were his tattoos really given him in Russian prisons, or are they an elaborate disguise created in England? We don’t know if Nikolai had a normal life before and gave it up to play out this ruse or if this undercover job is his redemption for past evils.

Tatiana’s Voice

One specific device intrigued me the first time I saw the film: the voice of Tatiana, the girl who dies early in the film giving birth. That voice is heard over at intervals, speaking passages from the diary that Anna finds in her purse and tries to get translated. What is the “source” of this voice? Against seeming logic, the voiceover becomes associated with people reading or translating the diary only fairly late in the film. The early instances occur over scenes where no one present could know the contents of the diary.

On my second viewing of the film, I took notes on the contexts in which the voice is heard, and I think this is a complete list:

First, as Anna initially opens the diary and finds the card for the restaurant; cut to her on bike heading for the restaurant.

Second, early the next evening as Anna rides her bike to the restaurant; the voice bridges the cut to Semyon drinking alone inside restaurant.

Third, during the scene of Nikolai having sex with the blonde prostitute.

Fourth, over Anna at hospital with baby Christina. Semyon comes in and says he has translated the diary—but doesn’t give the translation to her.

Fifth, shortly thereafter, Semyon leaves, and the voice resumes over a shot of Anna, upset by his implied threats. It bridges the cut to the dining room where the mother and Stepan are translating the diary. The voice of Tatiana dissolves into that of Stepan. This signals the point at which the family members finally become aware of the specific contents of the diary: that Semyon is the one who raped Tatiana and left her pregnant with Christina.

Sixth, a scene beginning with Nikolai in the restaurant alone, reading the diary. (Anna had given Nikolai the diary at the end of the previous scene, telling him to read it.) Semyon enters, gets the diary from him, and burns it.

Seventh, over a brief scene of Anna at home reading the translation of the diary. (This is immediately followed by a scene of Nikolai in his car watching Stepan go into a block of flats.) The implication is subtle, but in the most recent conversation between her and Nikolai, he has told her that she should raise Christina herself. Now perhaps she is searching the diary for evidence to justify such a decision.

Eighth, the final voiceover passage begins as Anna sits with Christina, whom she has adopted, in the garden; the voice bridges to the restaurant with Nikolai sitting alone, a bottle of vodka at his elbow. This is, I believe, the only repeated passage, being the same part as we hear in the first instance of voiceover. The passage ends, “That is why I left. To find a better life.”

This is two-edged. On the one hand, Nikolai does not have the option of leaving and finding the better life that he wishes he could have with Anna—the one we’ve just seen her leading with her family. On the other, he has the chance to save others from the fate that Tatiana suffered.

Only after the scene in which we see Nikolai reading the diary (the sixth occurrence of Tatiana’s voiceover) do we find out that he has been working against the gang—arranging for the blonde prostitute to be rescued by the police, spiriting Stepan away into hiding rather than murdering him. Yet it is not the diary’s contents that affects him and causes him to do such things. Reading the diary provides a plot point, giving him the vital clue that Semyon is Christina’s father, allowing him to tell the police how to test for DNA and convict Semyon of statutory rape.

The first four instances of the voiceover are not associated with anyone reading the diary. The last four are: Stepan translating it, Anna reading it, Nikolai reading it, and finally Nikolai apparently remembering it as he sits in place of Semyon in the restaurant. Seeing the film the first time, at the end I wondered if perhaps Tatiana’s voice becomes retrospectively linked to Nikolai, who sacrifices his own chance to happiness to continue battling the system of human trafficking that had victimized her.

Watching Eastern Promises again, I realized that the device is not that straightforward. Yet just as learning late in the film about Nikolai’s long undercover work against the vory v zakone shifts the implications of almost everything we have seen, so the resonance of the voiceover passages changes upon re-viewing. All the occurrences of it seem to lead up to the epilogue and to link our privileged access to Tatiana’s writings to our special knowledge of Nikolai’s role in so much of what has happened.

The voiceover motif has other functions. It keeps reminding us of the diary, which is crucial to the plot in several ways. It provides exposition about Tatiana’s life and about the methods used by the Russian mafia to lure girls and women into leaving their homes. Indeed, the device is typical of the narration, which remains quite objective and informative on the whole, moving between the two central characters in an even-handed fashion and even showing the other major characters when those two are not present. The voiceover becomes another means that the narration uses to inform us about the one character who disappears from the scene almost immediately.

Only at the end does the narration settle with one of the characters. We have seen Anna, finally happy in motherhood after having suffered a miscarriage shortly before the action of the plot began. The film ends with Nikolai, briefly lingering over his grim situation and allowing us to picture what his life will be like. That moment, I think, was where I came to associate Tatiana’s voiceover primarily with him.

Figuring backward

Some reviewers have compared Eastern Promises with A History of Violence primarily in qualitative terms. Is the second film inferior to the first? As good? Better?

They’re both very good. If more films these days were as good as either, we’d complain a lot less. Still, upon viewing each a second time in preparing to write this entry, I became convinced that Eastern Promises is even better than its predecessor. A History of Violence is a relatively simple film, and it remained much as I had remembered it. Revisiting Eastern Promises only a week after my first viewing, I saw far more in it.

The character of Kirill, Semyon’s son and apparent heir, is more complex. More importantly, Nikolai’s involvement in the affairs of the family’s gang activities is hinted to be far more direct than his modest standing as a “driver” would indicate. Indeed, there is a strong suggestion dropped that Nikolai caused the murder of Soyka (the shocking throat-slitting in the barber shop that opens the film). In the scene after Kirill gives Nikolai a truckload of champagne, Nikolai talks with Semyon and explains that the murder had been committed because Soyka was “talking about” Kirill. It’s evident that Nikolai himself could have been the source of any such notions about Soyka. There are other moments when we are led to contemplate the dense weave of possible causes and effects underlying the narrative.

It’s a rich film indeed. At the beginning I cautioned that you should see it before reading this entry. If you’ve done that, now I suggest seeing it again.

[Added October 18: I’m grateful to Eric Dienstfrey, who has responded to this entry with an intriguing suggestion about the “reversal” trait I noticed in these two films: “I think complementary films exist through most of Cronenberg’s career. Dead Ringers and M. Butterfly are two that come to mind, both films being about Jeremy Irons — to reference the old Woody Allen joke — at two with himself, either as twins, or internally as both a gay and straight individual. I also like the complement between Videodrome and The Dead Zone. In Videodrome, Woods loses control as he becomes more and more sadistic, whereas in The Dead Zone, Walken loses control as he becomes more and more heroic.”]

Do filmmakers deserve the last word?

DB here:

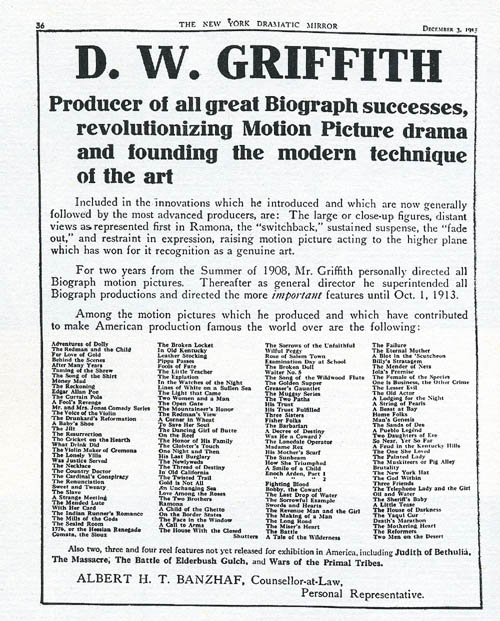

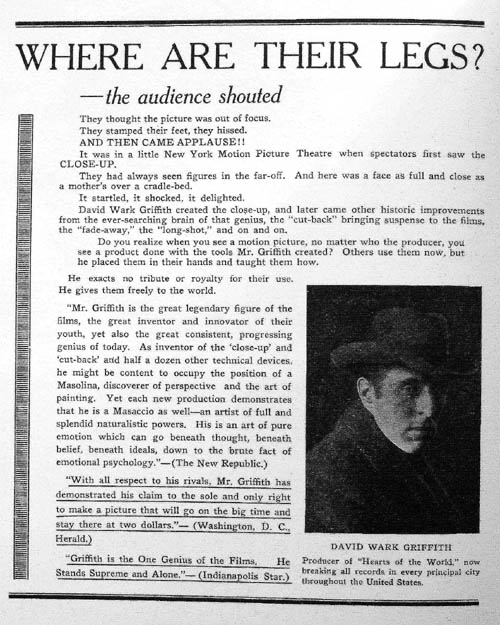

On 3 December 1913, the above advertisement appeared in the New York Dramatic Mirror. D. W. Griffith had left the American Biograph company and set out on an independent path that would lead to The Birth of a Nation and beyond. Because Biograph never credited directors, casts, or crews, he wanted to make sure that the professional community was aware of his contributions. Not only did he point out that he had made several of the most noteworthy Biograph films; he also took credit for new techniques. He introduced, he claims, the close-up, sustained suspense, restrained acting, “distant views” (presumably picturesque long-shots of the action), and the “switchback,” his term for crosscutting—that editing tactic that alternates shots of different actions occurring at the same time.

Griffith’s bid for credit was a shrewd move for his career, and it had repercussions after the stunning success of The Birth of a Nation two years later. Many historians took Griffith at his word and credited him with the breakthroughs he listed. He became known as the father of “film grammar” or “film language.” The idea hung on for decades. Here’s the normally perceptive Dwight Macdonald, criticizing Dreyer’s Gertrud for being anachronistic:

He just sets up his camera and photographs people talking to each other, usually sitting down, just the way it used to be done before Griffith made a few technical innovations. (1)

Filmmakers believed the Griffith story too. Orson Welles wrote of the “founding father” in 1960:

Every filmmaker who has followed him has done just that: followed him. He made the first close-up and moved the first camera. (2)

In the late 1970s a new generation of early-cinema scholars gave us a more nuanced account of Griffith’s place in history. They pointed out that most of the innovations he claimed either predated his Biograph work, (3) or appeared simultaneously and independently in Europe and in other American films. Some Griffith partisans had already conceded this, but they maintained that he was the great synthesizer of these devices, and that he used them with a vigor and vividness that surpassed the sources.

That judgment seems right in part, but Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Barry Salt, Kristin Thompson, Joyce Jesniowski, and other early-cinema researchers have drawn a more complicated picture. (4) Griffith did speed up cutting and devote an unusual number of shots to characters entering and leaving locales. But these innovations weren’t usually recognized as original by previous historians. More interestingly, much of what Griffith did was not taken up by his successors. His technique was idiosyncratic in many respects. By 1915 younger directors like Walsh, Dwan, and DeMille were forging a smoother style that would be more characteristic of mainstream storytelling cinema than Griffith’s somewhat eccentric scene breakdowns. Instead of creating film language, he spoke a forceful but often unique dialect.

The New York Dramatic Mirror ad coaxes me to reflect on how filmmakers have shaped critics’ and historians’ responses to their work. Hawks and Hitchcock developed a repertory of ideas, opinions, and anecdotes to be trotted out on any occasion. Today, directors write books, give interviews, appear on infotainment shows, and provide DVD commentary. We know that many of the talking points are planned as part of the film’s publicity campaign, and journalists dutifully follow the lead. (In Chapter 4 of The Frodo Franchise, Kristin discusses how this happened with Lord of the Rings.) For many decades, in short, filmmakers have been steering critics and viewers toward certain ways of understanding their films. How much should we be bound by the way the filmmaker positions the film?

Deep focus and deep analysis

Citizen Kane (1941).

Determining intentions is tricky, of course. Still, I think that in many cases we can reconstruct a plausible sense of an artist’s purposes on the basis of the artwork, the historical context, surviving evidence, and other information. (5) This may or may not correspond to what the artist says on a particular occasion. For now, I want simply to point to one instance in which filmmakers have shaped critical uptake, with results that are both illuminating and limiting.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, André Bazin, one of the great theorists and critics of cinema, argued that Orson Welles and William Wyler created a sort of revolution in filmmaking. They staged a shot’s action in several planes, some quite close to the camera, and maintained more or less sharp focus in all of them. Bazin claimed that Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons and Wyler’s The Little Foxes and The Best Years of Our Lives constituted “a dialectical step forward in film language.”

Their “deep-focus” style, he claimed, produced a more profound realism than had been seen before because they respected the integrity of physical space and time. According to Bazin, traditional cutting breaks the world into bits, a series of close-ups and long shots. But Welles and Wyler give us the world as a seamless whole. The scene unfolds in all its actual duration and depth. Moreover, their style captured the way we see the world; given deep compositions, we must choose what to look at, foreground or background, just as we must choose in reality. Bazin wrote of Wyler:

Thanks to depth of field, at times augmented by action taking place simultaneously on several plane, the viewer is at least given the opportunity in the end to edit the scene himself, to select the aspects of it to which he will attend. (6)

While granting differences between the directors, Bazin said much the same about Welles, whose depth of field “forces the spectator to participate in the meaning of the film by distinguishing the implicit relations” and creates “a psychological realism which brings the spectator back to the real conditions of perception” (7).

In addition, Bazin pointed out, this sort of composition was artistically efficient. The deep shot could supply both a close-up and a long-shot in the same framing—a synthesis of what traditional editing had given in separate shots. Bazin wove all these ideas into a larger theory that cinema was inherently a realistic medium, bound to photographic recording, and Welles and Wyler had discovered one path to artistic expression without violating the medium’s biases.

There are many objections to Bazin’s argument, some of which I’ve rehearsed in On the History of Film Style. My point here is that Bazin was presenting analytical points that stemmed from publicity put out by Welles, Wyler, and especially their talented cinematographer Gregg Toland.

In a 1941 article in American Cinematographer, Toland talked freely about how he sought “realism” in Citizen Kane. The audience must feel it is “looking at reality, rather than merely a movie.” Key to this was avoiding cuts by means of long takes and great depth of field, combining “what would conventionally be made as two separate shots—a close-up and an insert—into a single, non-dollying shot.”(8) Toland defended his sometimes extreme stylistic experimentation on grounds of realism and production efficiency, criteria that carried some weight in his professional community of cinematographers and technicians. (9)

Toland’s campaign for his style addressed the general public too. For Popular Photography he wrote an article (10) explaining again that his “pan-focus” technique captured the conditions of real-life vision, in which everything appears in sharp focus. A still broader audience encountered a Life feature in the same year (11), explaining Toland’s approach with specially-made illustrations. Two samples show selective focus, one focused on the background, the other on the foreground.

An accompanying photo shows pan-focus at work, with Toland in frame center, an actor in the background, and Toland’s camera assistant in the foreground.

In sum, Toland’s publicity prepared viewers, both professional and nonprofessional, for an odd-looking movie.

Throughout the 1940s, Welles and Wyler wrote and gave more interviews, often insisting that their films invited greater participation on the part of spectators. In a crucial 1947 statement, Wyler noted:

Gregg Toland’s remarkable facility for handling background and foreground action has enabled me over a period of six pictures he has photographed to develop a better technique for staging my scenes. For example, I can have action and reaction in the same shot, without having to cut back and forth from individual cuts of the characters. This makes for smooth continuity, an almost effortless flow of the scene, for much more interesting composition in each shot, and lets the spectator look from one to the other character at his own will, do his own cutting. (12)

Some of this publicity material made its way into French translation after the liberation of Paris, just as Kane, The Little Foxes, and other films were arriving too. Bazin and his contemporaries picked up the claims that these films broke the rules. Deep-focus cinematography became, in the hands of critics, a revolutionary new technique. They presented it as their discovery, not something laid out in the films’ publicity.

But the case involved, as Huck Finn might say, some stretchers. Watching the baroque and expressionist Kane, it’s hard to square it with normal notions of realism, and we may suspect Toland of special pleading. Some of Toland’s purported innovations, such as low-angle shots showing ceilings, had been seen before. Even the signature Toland look, with cramped, deep compositions shot from below, can be found across the history of cinema before Kane. Here is a shot from the 1939 Russian film, The Great Citizen, Part 2 by Friedrich Ermler.

More seriously, some of Toland’s accounts of Kane swerve close to deception. For decades people presupposed that dazzling shots like these were made with wide-angle lenses.

Yet the deep focus in the first image was accomplished by means of a back-projected film showing the boy Kane in the window, while the second image is a multiple exposure. The glass and medicine bottle were shot separately against a black background, then the film was wound back and the action in the middle ground and background were shot. (And even the middle-ground material, Susan in bed, is notably out of focus.) I suspect that the flashy deep-focus illustration in Life, shot with a still camera, is a multiple exposure too. In any event, much of the depth of field on display in Kane couldn’t have been achieved by straight photography. (13)

RKO’s special-effects department had years of experience with back projection and optical printing, notably in the handling of the leopard in Bringing Up Baby, so many of Kane‘s boldest depth shots were assigned to them. But here is all that Toland has to say on the subject:

RKO special-effects expert Vernon Walker, ASC, and his staff handled their part of the production—a by no means inconsiderable assignment—with ability and fine understanding. (14)

Kane’s reliance on rephotography deals a blow to Bazin’s commitment to film as a medium committed to recording an event in front the camera. Instead, the film becomes an ancestor of the sort of extreme artificiality we now associate with computer-generated imagery.

Despite these difficulties, Toland’s ideas sensitized filmmakers and critics to deep space as an expressive cinematic device. Modified forms of the deep-focus style became a major creative tradition in black-and-white cinema, lasting well into the 1960s. Bazin’s analysis certainly developed Toland’s ideas in original directions, and he creatively assimilated what Toland and his directors said into an illuminating general account of the history of film style. None of these creators and critics were probably aware of the remarkable depth apparent in pre-1920 cinema, or in Japanese and Soviet film of the 1930s. Their claims taught us to notice depth, even though we could then go on to discover examples that undercut Toland’s claims to originality.

Some little things to grasp at

I assume that Toland and his directors were sincerely trying to experiment, however much they may have packaged their efforts to appeal to viewers’ and critics’ tastes. But sometimes artists aren’t so sincere. By the 1950s, we have directors who started out as film critics, and they realized that they could guide the agenda. Here is Claude Chabrol:

I need a degree of critical support for my films to succeed: without that they can fall flat on their faces. So, what do you have to do? You have to help the critics over their notices, right? So, I give them a hand. “Try with Eliot and see if you find me there.” Or “How do you fancy Racine?” I give them some little things to grasp at. In Le Boucher I stuck Balzac there in the middle, and they threw themselves on it like poverty upon the world. It’s not good to leave them staring at a blank sheet of paper, no knowing how to begin. . . . “This film is definitely Balzacian,” and there you are; after that they can go on to say whatever they want. (15)

Chabrol is unusually cynical, but surely some filmmakers are strategic in this way. I’d guess that a good number of independent directors pick up on currents in the culture and more or less self-consciously link those to their film.

Today, in press junkets directors can feed the same talking points to reporters over and over again. An example I discuss in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema is the way that Chaos theory has been invoked to give weight to films centering on networks and fortuitous connections. As I read interview after interview, I thought I’d scream if I encountered one more reference to a butterfly flapping its wings.

More recently, Paul Greengrass gave critics some help when he suggested that the jumpy cutting and spasmodic handheld camera of The Bourne Ultimatum suggested the protagonist’s subjective point of view–presumably, Jason’s psychological disorientation and frantic scanning of his surroundings. I expressed skepticism about this on an earlier blog entry, Anne Thompson replied on her blog, and I returned to the subject again. Any director’s statement of purpose is interesting in itself, but it should be assessed in relation to the evidence we detect onscreen.

Another recent instance: the new Taschen book on Michael Mann. The luscious pictures, mainly from Mann’s archive, are the volume’s raison d’etre, but the filmmaker seems to have placed unusual demands on the text. F. X. Feeney writes:

An earlier version of this book completed by another writer attempted (in a spirit of sincere praise) to treat Mann’s films as reactions against film traditions, as subversions of genre. This fetched a rebuke from Mann: “It’s irrelevant and neither accurate nor authentic to compare my films to other films because they don’t proceed from genre conventions and then deviate from those conventions. They proceed from life. For better or worse, what I’ve seen and heard and learned on my own is the origin of this material. Maybe the film medium by nature spawns conventions, because we all built on what’s gone before, but the content and themes of my films are not facile and derivative. They are drawn from life experience.” (16)

We have to wonder if Mann’s objection played a role in eliminating the earlier writer’s version. If that happened, it’s an unusually strong instance of a director’s holding sway over critical commentary. (17)

In the text we have, Feeney provides a chronological account of Mann’s career: plot synopses, thematic commentary, production background. There’s no discussion of broader historical trends, such as the migration of TV directors into film, the creative options available in 1980s-1990s Hollywood, the development of self-conscious pictorialism in modern film, the possibility of genre films becoming art-films or prestige pictures, or the changes in media culture or American society. All of these lines of inquiry would require comparing Mann with other filmmakers. It remains for other writers, perhaps without the director’s cooperation, to put Mann’s achievement into such contexts.

It’s always vital to listen to filmmakers, but we shouldn’t limit our analysis to what they highlight. We can detect things that they didn’t deliberately put into their films, and we can sometimes find traces of things they don’t know they know. For example, virtually no director has explained in detail his or her preferred mechanics for staging a scene, indicating choices about blocking, entrances and exits, actors’ business, and the like. Such craft skills are presumably so intuitive that they aren’t easy to spell out. Often we must reconstruct the director’s intuitive purposes from the regularities of what we find onscreen. (For examples, see this site here, here, and here.) And it doesn’t hurt, especially in this age of hype, to be a little skeptical and pursue what we think is interesting, whether or not a director has flagged it as worth noticing.

(1) Macdonald, “Gertrud,” Esquire (December 1965), 86.

(2) Quoted in Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum, This is Orson Welles (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 21).

(3) Such would seem to be the case of the close-up, which of course is found very early in film history. But Griffith’s idea of a close-up may not correspond to ours. More on this in a later blog, perhaps.

(4) I give an overview of this rich body of research in Chapter 5 of On the History of Film Style. See also various entries in the Encyclopedia of Early Cinema, ed. Richard Abel (New York: Routledge, 2005).

(5) The most detailed argument for this view I know is Paisley Livingston’s book Art and Intention: A Philosophical Study.

(6) “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo (New York: Routledge, 1997), 8.

(7) Orson Welles: A Critical View, trans. Jonathan Rosenbaum (New York: Harper and Row, 1978) 80).

(8) Toland, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” American Cinematographer 22, 2 (February 1941), 54, 80.

(9) See the discussion in Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 345-349.

(10) Toland, “How I Broke the Rules in Citizen Kane,” Popular Photography (June 1941), 55, 90-91.

(11) “Orson Welles: Once a Child Prodigy, He Has Never Quite Grown Up,” Life (May 26, 1941), 110-111.

(12) Wyler, “No Magic Wand,” The Screen Writer (February 1947), 10.

(13) Peter Bogdanovich was to my knowledge the first person to publish some of this information; see “The Kane Mutiny,” Esquire 77, 4 (October 1972), 99-105, 180-90.

(14) Toland, “Realism,” 80.

(15) “Chabrol Talks to Rui Noguera and Nicoletta Zalaffi,” Sight and Sound 40, 1 (Winter 1970-1971), 6.

(16) F. X. Feeney, Michael Mann (Cologne: Taschen, 2006), 21.

(17) Mann’s reasoning puzzles me. He insists that his films can’t be compared to others along any dimensions, especially thematic ones. Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his. Moreover, what about comparisons on grounds of technique, surely one of the most striking and admired features of Mann’s work? For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).

Ad in Wid’s Year Book 1918.

PS: 15 October: I’ve received a clarification from Paul Duncan, editor of F. X. Feeney’s Michael Mann book for Taschen. He expresses general agreement with my suggestions about how directors shape the uptake of their work, but he explains that the Mann book isn’t an instance of it. Here are the comments bearing on my blog entry.

In reply to my suggestion of other avenues to explore about Mann’s career:

In fairness to F.X. Feeney, he only had 25,000 words to cover Mann’s career, and all the subjects you write about are really outside the scope of the book. It sounds as though these are subjects that you would like to explore, and I can’t wait to read them in a future book or blog.

As for whether Mann exercised some control over the book’s final form, which I float as one possible explanation for its compass:

First, you speculate whether Mann caused the first version of the book to be scrapped, i.e. He exerted editorial control/censorship over the book. This is not the case, and if it was, do you think that he would have allowed F.X. to write that in the published version of the book?

In Note 17 appended to Feeney’s quote, you write: “Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his.” If you had continued Mann’s quote, you would have reported the following: “I don’t look at the excellent French director Jean-Pierre Melville to decide how to tell the story in Thief. I meet thieves. And I guarantee you the reason Melville’s Le Samourai 1967) has authenticity, the reason Raoul Walsh’s White Heat (1949) has authenticity, is because those film-makers knew thieves, too.” I do not see any evidence here that Mann suggests that his films are more lifelike than other directors’. Only that his films stem from life like other films stem from life.

Also, in Note 17, you write: “For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).” The reason Mann hates the word “style”—and I apologize for not making this clear in the book—is because after producing the Miami Vice TV show, he was forever referred to as a stylist, and the “style” of the show was all anybody ever talked about. The implication was that Mann is a director of style without substance. Subsequently, Mann has been very wary of the word, and discussion of it, because it puts undue weight on one aspect of his work.

Finally, I would like to explain a little of the working method with Mann on the book. The book was researched and written during rehearsal, filming and editing of Collateral. F.X. wrote the text and was given full access to everything that Mann had said in interviews. Mann then read and annotated the text, and this was discussed face-to-face with F.X. Most of these annotations were of a factual nature, correcting dates, being precise about the sequence of events, and to correct misinterpretations of his comments in previous interviews. However, they would also bring up new comments from Mann about his work. F.X. then rewrote some texts to include Mann’s comments, and then F.X. wrote his replies. In this way, the book became more of a dialogue between Mann and F.X. and is stronger for it I feel. So, in this case, the filmmaker did not get the last word.

I thank Paul for his clarifications, which should be of interest to all the book’s readers. On only two matters do we disagree.

First, Feeney’s book achieves what it set out to achieve, and it deserves credit for giving us valuable information about Mann in a clear, pungent style. And no one expects a Taschen book to be an in-depth monograph covering all aspects of a director’s career. But I still think that length limits don’t prevent an author from raising the contextual issues I mention. Many articles manage to address matters that go beyond the sort of career survey that Feeney provides, so there are ways to sketch such issues in an abbreviated way. I inferred, erroneously, that the choice not to tackle them could have been related to Mann’s own views on the comparative dimension that such issues tend to rely on.

Secondly, a minor matter: The fact that Mann can invoke Melville and Walsh on films about thieves suggests that a comparative perspective is valuable; he’s including himself in the company of directors who know their subjects from life, in explicit contrast to those who don’t. I didn’t include the extra sentences because I thought that they simply provided further signs of the contradiction I found in Mann’s own position—that his films can’t be compared to other directors’ works.

More light from the East

Useless (Jia Zhang-ke, China, 2007).

DB’s last communiqué from the 2007 Vancouver International Film Festival:

I’m so taken with José Luis Guerin’s En la ciudad de Sylvia (Spain/ France) that I’ll be devoting a separate blog entry to it soon. At Vancouver it was projected with his Unas fotos en la ciudad del Sylvia, a remarkable sketchpad for and rumination on the feature. Rubbed together, the two films throw off sparks. En la ciudad is in color and very tightly constructed, Unas fotos consists of hundreds of black-and-white stills linked by associations and intertitles, with no sound accompaniment. Guerin, an admirer of Murnau, says that as a young man he watched old films in “a sacred silence” and he wanted to try something similar.

Unas fotos may not be factual—call it a lyrical documentary—but it illuminates En la ciudad in striking ways and is intriguing in its own right. Structured as a quest for a woman the narrator met 22 years ago, the film moves across several cities and invokes as its patrons Dante and Petrarch, each of whom yearned for an unattainable woman. But this isn’t exactly a photo-film à la Marker’s La jetée; it uses dissolves, superimpositions, and staggered phases of action to suggest movement. The subjects? Dozens of women photographed in streets and trams. Some will find a creepy edge to the movie, but it didn’t strike me as the obsessions of a stalker. Guerin becomes sort of a paparazzo for non-celebs, capturing the many looks of ordinary women.

Watch this space for more on the many looks of Sylvia. For now, more Asian highlights from Vancouver.

Fujian Blue.

Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai have reunited for The Mad Detective (Hong Kong), which is as off-balance as you’d expect from its premise. Evidently spun off those TV series that feature telepathic profilers, the film stars Lau Ching-wan as a detective who solves cases by intuiting crooks’ “inner personalities.” We’re introduced to him crawling into a suitcase and asking his partner to throw it downstairs. After a few bumpy descents, he flops out and names the man who packed up a girl’s body the same way. Soon Lau is mentally reenacting a convenience-store robbery, and To/Wai cut together various versions of it as he plays with the possibilities.

Years after Lau leaves the force, his partner brings him back as a consultant to another case. By now, though, our mentalist has gone mental. The filmmakers get comic mileage, and some genuine poignancy, out of intercutting his hallucinations with what’s really happening. Lau envisions multiple personalities within the man they’re hunting, and as he traces out clues each personality flares up. To and Wai carry their dotty premise to a vigorous climax that multiplies the mirror confusions of both Lady from Shanghai and The Longest Nite. The brilliant sound designer Martin Chappell is back on the Milkyway team, making the effects and music magnify Lau’s heroic disintegration.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Secret Sunshine earns its 130-minute length, because Lee needs time to do several things. He traces the assimilation of a widow and her little boy into a rural town. Then he must follow the remorseless playing out of a harrowing crime. He makes plausible her succumbing to fundamentalist Christianity and her growing conviction that she needs to forgive the criminal. And there are more changes to come.

For me the most unforgettable moment was the heroine’s appalled confrontation, in a prison visiting room, with the man who wronged her. His unexpected reaction dramatizes how religious faith can cultivate both emotional security and an almost invincible smugness. Jeon Do-yeon won the Best Actress award at Venice for her nuanced performance, and Song Kang-ho, best known for The Host and Memories of Murder, lightens the somber affair playing a man of indomitable cheerfulness and compassion.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

Off to China for Fujian Blue by Robin Weng (Weng Shouming). The setting is the southeastern coast, a jumping-off point for illegal immigration. The plotline has two lightly connected strands. In one, a boys’ gang tries to blackmail straying wives by photographing them with boyfriends, going so far as to sneak in homes and catch the couples sleeping together. The other plot strand presents Dragon, a boy who’s trying to sneak out of China and make money overseas. The whole affair is reminiscent of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Boys from Fengkuei, and in Dragon’s story we can spot overtones of Hou’s distant, dedramatized imagery. Yet Weng adds original touches as well, including an almost subliminal ghost of London across the blue skies of the China straits.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

In the second episode . . . But why give away any more? In this relaxed, peculiar little film Beckett meets the Buñuel of The Milky Way and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. As the enigmatic men without pasts or even psychologies wound their way through the long shots, Zheng’s quietly comic incongruities won me over long before the last dog had barked and the last ball had bounced.

Jia Zhang-ke is known principally for fiction films like Platform, The World, and Still Life, but from the start of his career he has shown himself a gifted documentarist as well. His In Public (2001) is a subtle experiment in social observation, and Dong (2006) made an enlightening companion piece to Still Life. Useless is more conceptual and loosely structured than Dong. Omitting voice-overs, Useless offers a free fantasia on the theme of China as apparel-house to the world.

The first section of the film presents images of workers in Guangdong factories as they cut, sew, and package garments. Jia’s camera refuses the bumpiness of handheld coverage; it opts for glissando tracking shots along and around endless rows of people bent over machines. (Now that fiction films try to look more like documentaries, one way to innovate in documentaries may involve making them look as polished as fiction films.) Jia also gives us glimpses of workers breaking for lunch and visiting the infirmary for treatment.

In a second section, Useless follows the success of a fashion house called Exception, run by Ma Ke. Her new clothing line Inutile (Useless) consist of handmade coats and pants that are stiff and heavy, almost armor-like, and that flaunt their ties to work and nature. (Some outfits are buried for a while to season.) Ending this part with Ma’s Paris show, in which the models’ faces are daubed with blackface, Jia moves back to China and the industrial wasteland of Fenyang Shaoxi. There he concentrates on home-based spinning and sewing. Neighborhood tailors patch up people’s garments while the locals descend into the coalmines. A former tailor tells us that he gave up his work because large-scale clothes production rendered him useless.

Jia’s juxtaposition of three layers of the Chinese clothes business evokes major aspects of the country’s industry: mass production, efforts toward upmarket branding, and more traditional artisanal work. Without being didactic, he uses associational form to suggest critical contrasts. The miners’ sooty faces recall the Parisian models’ makeup, and their stiff workclothes hanging on a washline evoke the artificially distressed Inutile look. What, the film asks, is useless? Jia shows industrial China’s effort to move ahead on many fronts, while also forcefully reminding us of what is left behind.

Thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Mark Peranson, and all their colleagues for a wonderful festival. They’re so relaxed and amiable, they make it look easy to mount 16 days crammed with movies. Be sure to check on CinemaScope, the vigorous and unpredictable magazine that makes its home in Vancouver. It gives you many gems online, but it’s well worth subscribing to.

Alan Franey, Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival; PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager; and Mark Peranson, Program Associate and Editor of Cinema Scope.

Asian media empires, and the greatest of all filmmakers

DB here:

I owe you a final report on my viewings in Vancouver, but while I’m preparing that, I want to signal three publications, two printed books and one online book.

America seems to have cornered the market in branded entertainment. Movies and comics have given us Mickey Mouse, Shrek, Barney the dinosaur, Batman, Jughead, and all those other lovable characters you can’t escape. Once in a while another country gets into the game, as with Tintin (Belgium), the Smurfs (Belgium), and the Teletubbies (Britain). But for sheer numbers, the US’s only real rival, it seems, is Japan.

The cliché is that the Japanese make the hardware and we make the software. But Astro Boy (originally Mighty Atom), Speed Racer, Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, Sailor Moon, Pokémon, Cutie Honey, and Super Mario Brothers beg to differ. And if Zatoichi and Godzilla add their weight to the argument, you’ll back off fast. The Japanese have given the world an unending spate of sagas and characters, often of marked peculiarity. Ranma ½ changes from a boy to a girl and back again, and Mothra, even just being himself, is fairly creepy.

All of which makes Ken Belson and Brian Bremner’s Hello Kitty: The Remarkable Story of Sanrio and the Billion Dollar Feline Phenomenon (Wiley) an informative study and a breezy read. The pudgy cat with no mouth generates about $500 million in annual sales, half of Sanrio’s total, and she adorns over 20,000 products, including vibrators.

All of which makes Ken Belson and Brian Bremner’s Hello Kitty: The Remarkable Story of Sanrio and the Billion Dollar Feline Phenomenon (Wiley) an informative study and a breezy read. The pudgy cat with no mouth generates about $500 million in annual sales, half of Sanrio’s total, and she adorns over 20,000 products, including vibrators.

Belson and Bremner trace Ms. Kitty’s rise from humble beginnings in 1974 to her current status as a media superstar. Just as important, they put her in several intriguing contexts. They trace the rise of the kawaii (cuteness) sensibility throughout Asia, where Peanuts‘ Snoopy became the model. They show that Miss Kitty is emblematic of Japan’s shift from “hard” manufacturing industries to “soft” culture-based ones like comics and videogames. Some consumers, though, choke on all this sugar, and the authors haven’t omitted mention of those media jammers who want to turn our heroine into a hellcat.

The book is especially good at characterizing the distinctive Japanese belief that a product must arouse an emotional attachment in the consumer. Sony does it through sleek design, Tamagotchi the digital pet did it through guilt-tripping. Ms. Kitty might seem the epitome of blandness, her awww quotient and neoteny-driven features rendering her vacuous. Yet the lady has a touch of mystery. You’ve seen a smile without a cat, but here is a cat without a smile. Snoopy shamelessly exposes his fantasy life, but who knows what she’s feeling? Lust? Caution? Is she quietly judging us? Fill in the blank.

For a more comprehensive analysis of how Asian media empires work, go to Michael Curtin’s brand-new Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV (University of California Press). Michael is a close friend and colleague, so in principle I’m biased; but I’d think this a terrific book if he were a stranger. Among many other things, it shows that media globalization isn’t a one-way flow, from Hollywood to ROTW (Rest of the World). Asian media are globalizing too, and the process is both fascinating and far-reaching.

For a more comprehensive analysis of how Asian media empires work, go to Michael Curtin’s brand-new Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV (University of California Press). Michael is a close friend and colleague, so in principle I’m biased; but I’d think this a terrific book if he were a stranger. Among many other things, it shows that media globalization isn’t a one-way flow, from Hollywood to ROTW (Rest of the World). Asian media are globalizing too, and the process is both fascinating and far-reaching.

The book provides both history and contemporary analysis. Michael shows that Shaw Bros. pioneered the concept of an entertainment conglomerate in Asia, and he traces their policies across several decades. The story starts in Hong Kong, with its curiously transnational film industry, but the tale sweeps across media (TV, telephony, internets) and territories: Taiwan, Singapore, and mainland China. Michael has interviewed many major players, so if you want to know what’s really behind Golden Harvest, Media Asia, China Star, Star TV, Celestial, and other companies, this is the place to go. In the area I know a little, Michael offers the shrewdest and strongest analysis of the rise and precipitous fall of the Hong Kong film industry I’ve seen.

Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience will attract scholars and business people wanting to understand the dynamics of Asian media. I think as well that fans of Asian film, music, and TV can get a lot out of it. If you’re put off by the first chapter’s theoretical layout, skip to chapter two and jump into the compelling story of how entrepreneurs from southern China assembled a media juggernaut that now enthralls over a billion spectators.

Finally, about a year ago on this blog I wrote an entry about the online arrival of my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, thanks to the publishing initiative of the Center for Japanese Studies at the University of Michigan. Now an improved online edition of this scarce out-of-print book has just gone online. You can download the whole shebang if you want.

Finally, about a year ago on this blog I wrote an entry about the online arrival of my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, thanks to the publishing initiative of the Center for Japanese Studies at the University of Michigan. Now an improved online edition of this scarce out-of-print book has just gone online. You can download the whole shebang if you want.

In the first version, posted a year ago, the pictures were hard to see, so we made digital versions of all the original stills. The monochrome ones look very nice, and the color ones (not an option for the print edition) look fine. In addition, if you click on a still in the sidebar, you can enlarge it and even download it. Thanks to web tsarina Meg Hamel, we have a permanent link in the list of books on the left.

There’s also a new introduction, in which I explain a bit about the background of the book, talk about the approach it takes, position it within trends of film studies, and suggest what Ozu means to me. My introduction also shows some rare pictures, including snaps from a strange exhibition about Ozu’s life. The exhibition has vanished now, but maybe that’s an appropriate tribute to an artist who made mutability everlastingly vivid.

A toast to Markus Nornes, Bruce Willoughby, Kristi Gehring, Terry Geitgey, and all the other people who took pains to make this improved online Ozu possible.