Archive for November 2007

Three nights of a dreamer

DB here:

The close-up blogathon launched by Matt Zoller Seitz is over, but it contains enough specimens and analyses for a hefty book. It also inspired Jim Emerson to devote a cine-lyric to the close-up. I missed the deadline, so I suppose that this constitutes my sideways contribution to Matt’s enterprise.

Sideways, because a full-blown analysis of In the City of Sylvia (En la ciudad de Sylvia; Dans la ville de Sylvie) would be a breach of decorum. Most people haven’t heard of this new film by José Luis Guerin, let alone seen it. I saw it at the Vancouver festival in September, and it will make its way through the festival circuit over the coming months and should show up on cable or DVD thereafter. But apart from calling attention to it as a remarkable film, I want to look at one of its most absorbing sequences and suggest some of its originality. Lee Marshall has already pointed out one of Sylvia‘s arresting features:

Guerin seems to have created pure drama without recourse to story. We’re always taught that story is the engine of drama. Not here: somehow Guerin has created an almost plotless film that has the dramatic tension of vintage Hitchcock. (1)

Although the story situation is slight, the tension we feel springs partly from vivid stylistic patterns. In other words: Minimal and uncertain story action is heightened by engaging visual narration. This narration in turn derives its power from one of the most traditional devices of filmic storytelling.

Consider the other person’s point of view

The point-of-view shot is a mainstay of cinematic storytelling, and its history is an intriguing one. Many of the earliest examples we have are motivated as views through optical gadgets. Two films by the Englishman G. A. Smith, both from 1900, handily show the options. Grandma’s Reading Glass justifies the point-of-view image as what the boy sees when he peers at granny through her big magnifier.

Smith’s As Seen through a Telescope motivates the cut-in POV shot as what our dirty old man in the foreground has an eye for.

Fairly soon, this use of the magnifying POV shot was mingling with more straightforward ones. In The Birth of a Nation (1915), D. W. Griffith offers a rough-edged example. When the Stoneman brother and sister visit Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination, we see Elsie pointing out the famous actor John Wilkes Booth.

Booth is framed in an iris, which Griffith often uses to underscore an important image. But when Elsie studies Booth through her opera glasses, Griffith, usually not fastidious about such things, supplies the same irised image, now doing duty for the sort of magnifier-masking we get in the Smith films.

Presumably a more consistent technique would show Booth in long shot first, without the iris, and reserve the optical masking for replicating the view through the opera glasses. This is what happens in Ernst Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1926), which contains a sequence built entirely around crisscrossed character looks. (1)

The woman of the world Mrs. Erlynne arrives at the racetrack and creates a stir, causing many men to watch her from all over the grandstand.

Note that Lubitsch has gone beyond Griffith by fitting the angle of Shot B to the viewer’s orientation, looking up. There are so many POV shots that at one point Lubitsch simply shows her from different angles and deletes the shots of each watching man.

This is a fascinating example of a process we often see in stylistic history. An “overlearned” visual convention can be treated elliptically; the filmmaker can leave out bits and we’ll fill them in. The binocular masking suffices to let us know that Mrs. Erlynne is being studied from afar. Moreover, Lubitsch gets an expressive bonus from being so concise. Now it doesn’t matter who’s watching, just that somebody is—actually, a lot of somebodies.

Later, after much more byplay with people looking at one another and misunderstanding what they see, Mrs. Erlynne sits down. Three gossips have been studying her, but now their view is blocked. So one gossip has to twist around to spy on her, and Lubitsch obligingly gives us a slightly tipped point-of-view framing—a full shot, without masking.

Adjusting her binoculars, the gossip is able to get a bigger view of Mrs. Erlynne, and she racks focus gleefully to catch a gray hair peeping out.

The visual narration in this sequence, already perfectly modulated, supplies the stylistic premise for Hitchcock’s Rear Window and all of its progeny, most recently Disturbia (2007). What might be overlooked is that by the 1920s the view through a device—field glasses, a microscope, a surveillance camera—had become a special, marked case. From then till now, the default POV pattern is the simple shot of a character looking, followed by an unadorned shot of what that person sees, from more or less the correct standpoint. Lubitsch’s sideways shot of the gossip’s view of Mrs. Erlynne, casually introduced, exemplifies the modern norm for presenting a character’s vision, and it’s so common that we seldom notice it.

POV shots: The basics

In his book Point of View in the Cinema, Edward Branigan itemizes the cues that the filmmaker can manipulate in creating a POV construction. (2) To simplify somewhat: Shot A shows a point in space and a character glance from that point. Shot B is taken from a camera position more or less approximating the point in A, and it shows an object. The shot-change presumes temporal continuity between A and B, and we assume as well that the character is aware of the object shown in B.

This seems like a complicated way of stating the obvious, but by teasing these elements apart, Branigan shows that each one can be manipulated in intriguing ways. For example, you can create a disorienting moment by violating the condition of temporal continuity. Ozu does this in Early Summer (1951), when Noriko and Aya decide to peek in at the man Noriko almost married. The two women tiptoe down a hall toward us as the camera tracks slowly backward. Ozu cuts to a forward-tracking shot that momentarily suggests a reverse angle POV on the corridor.

In fact, however, the camera movement is revealed to be the first shot of a new scene, among different characters, and we won’t ever see the man the two women went to spy on.

Here’s another interesting case, not cited by Branigan. In Halloween (1978), John Carpenter shows Laurie looking out a window and seeing Michael Myers in his mask, standing between fluttering washlines.

Cut back to Laurie, now frowning slightly.

Cut to a second POV shot; but now Michael has vanished.

This simple change in shot B’s object, Michael himself, has an uncanny effect. Did Michael just walk away from the washline? If so, this is an odd way to present it. Why not show him walking away? Alternatively, did he just disappear? Surely not; Laurie would be shocked. Carpenter wins twice over. Without obviously violating realism or directly showing that Michael has supernatural powers, he gives Michael the ability to come and go in a ghostly fashion. By the end of the film, when he miraculously disappears after a fall that would kill an ordinary person, we are prepared to believe that he is indeed, as Dr. Sam Loomis says, the Boogyman.

Who is Sylvia? What is she that all the swains commend her?

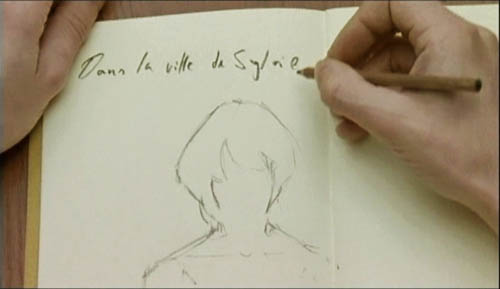

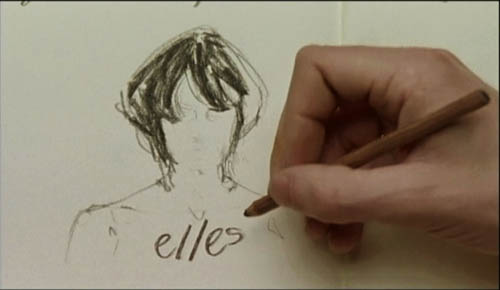

In the City of Sylvia centers on a young man staying at a hotel. We’re given no reason why he’s visiting the city, and no backstory about him. One day he’s sitting at a café. Now, across nearly twenty minutes of screen time he watches women and idly sketches them.

The sequence is a pleasure to watch, partly because of the constant refreshing of the image with faces, nearly all of them gorgeous, most of them female. Either Strasbourg has an extraordinary gene pool, or this café attracts only Ralph Lauren models. Yet the scene builds curiosity and suspense too, thanks to Guerin’s sustained and varied use of optical POV. He gives us an almost dialogue-free exploration of a cinematic space through one character’s optical viewpoint. (Stop reading here if you don’t want to know anything more about the film before you see it.)

The young man, known in Guerin’s companion film Unas fotos en la ciudad del Sylvia as the Dreamer, is almost expressionless as he scans the women’s faces. Slight shifts of his glance are accentuated by his habit of turning his head but keeping his eyes fixed. In over a hundred shots, Guerin uses some ingenious cinematic means to tease us into ever-greater absorption in the Dreamer’s visual grazing.

Fairly far into the sequence, Guerin gives us more or less the orthodox POV construction. The Dreamer looks at one woman at a table, and we see her return his look.

But here shot B isn’t really clean: the hands of the woman on the left sometimes block our view of the principal woman. This obtrusiveness is one of Guerin’s most basic strategies in the sequence. Inevitably, in passages before and after the cut I just showed, what the Dreamer is looking at is partially hidden in layers of faces and body parts.

Our prototype of the POV cut presumes a more or less single ‘point’ we are watching in shot B, but throughout this scene Guerin plays with this cue. He tantalizes us with several points to be observed, and he often obscures the most important ones. He also creates some startling juxtapositions. Near the very start we get this shot, which may or may not be the Dreamer’s POV.

By making the background girl seem to kiss the foreground guy, Guerin, as Eisenstein would say, “christens” his sequence. In effect, the image says: Watch out! Layered space will become important! When I saw this shot, I nearly jumped out of my seat.

The Dreamer is treated no differently, at least at the start. In most movies, the POV construction is set up with a clear, clean framing of our looker in shot A. Here, though, at the start of the scene Guerin peels away layers to get to our man. For the first six shots of the café, we don’t know he’s on the scene. Then he’s shown out of focus, in the background of more prominent action. The woman in the foreground has been primed to be the shot’s subject. At the moment she shifts her gaze and we try to read her expression, a second woman on the distant right shifts aside to reveal the Dreamer behind her.

Surely this is the most unemphatic entry of a protagonist we’ve seen in a while! Guerin is able to add planes to block the main ‘point’ of shot B because he’s working with long lenses, a crowded space, and careful choreography. Even focus plays a role, as in this case; our Dreamer is pretty hazy.

One upshot of this strategy is that we’re plunged into a “cubistic” space, in which slightly varied camera angles pick up bits of space we’ve seen in earlier combinations and oblige us to assemble it all in our head. Be thankful for the guy in the blue shirt above, for he plays an anchoring role in several setups that would otherwise float free.

It’s hard to convey in stills how much fascination and frustration that this teasing style creates. Like the Dreamer, we’re given only glimpses of the women, and even though we don’t know his purposes—is he just an artist in search of beauty? a serial killer picking out victims?—the partial views lure us at several levels. We try to complete the faces. We try to infer the women’s state of mind from their expressions and gestures, which are far more animated than our Dreamer’s.

And a search for story plays a part here. We’re primed for some action to start, and we browse through these shots looking for anything that might initiate it. Each face the Dreamer spots promises to kick-start a plot: when the Dreamer gets a full view of one of these women, perhaps things will get going.

Without giving away every detail, I’ll just say that the sequence has a strong visual arc as the Dreamer starts paying more and more attention to certain women. And just as he finally gets a full view of one fabulous face, his attention wanders to . . . another layer, this time one inside the café.

As he gapes at the woman inside, layers pile up, creating a cubistic climax of all the optical obstructions we’ve encountered.

The motif of reflections will take over the rest of the film’s visual design, and eventually we’ll see that some of the Dreamer’s drawings evoke the piled-up and sliced-up faces in the café shots.

Later in the film, the Dreamer will explain why he’s in the city and why he’s scanning women. We’ll have a tram ride that Guerin compares with Sunrise, and a scene in a music club that not only parallels the café sequence but evokes Manet. We’ll also have occasion to compare this film with Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer, a citation signaled from the outset.

All that is to come. Even if the later scenes weren’t as compelling as they are, this café sequence would make Sylvia one of the most adventurous films I’ve seen this year. By revising the simple, long-lived POV schema, Guerin has made it yield fresh feelings and implications. Like Lubitsch’s racetrack scene, this imaginative sequence provokes the jubilation you feel in the presence of calm, precise artistry.

(1) Lee Marshall, “Past Perfect,” Screen International (19 October 2007): 27. The web version is here, but it may require a subscription.

(2) I analyze the visual narration of Lady Windermere, which I think deserves to be ranked with Potemkin and Sunrise, in Narration in the Fiction Film (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 178-186.

(3) Edward R. Branigan, Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film (The Hague: Mouton, 1985), 102-121.

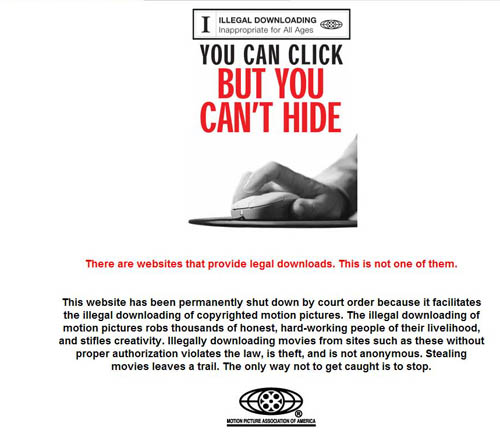

I was, and may still be, a spy for the MPAA

DB here:

The Motion Picture Association of America is the trade association of the major film production and distribution companies. Founded in 1922, it helped the Hollywood studios maintain their control of the US industry and foster its business abroad. (See Kristin’s book Exporting Entertainment for an explanation of how it worked.) In 1945 the MPAA split off its international efforts and created a subsidiary, the Motion Picture Export Association of America, which helped the majors move in a systematic way into world markets. The current MPAA members are the Big Six: Sony (Columbia), Buena Vista (Disney), Universal, Paramount, Warner Bros., and Twentieth Century Fox.

About fifteen months ago, the MPAA created a survey called My Movie Muse. Reading about it in Variety, I eagerly signed up. Every three or four months My Muse contacts me and asks me to answer some questions. At the end of the survey, I’m told that my name has been entered in a drawing for a gift certificate from Amazon.

I’ve never won. I’ve never heard who did. Maybe I won and the MPAA forgot to tell me.

The Movie Muse survey started last year with 7500 participants. You can join us by going to the website.

The initiative, according to MPAA head Dan Glickman, enables moviegoers to tell the industry their concerns.

People want to have input. They want to know that their movie viewing experiences are worth their time and money, and they want to know that our industry is hearing their criticisms and demands. In this age of participatory media, My Movie Muse will give consumers an opportunity to be heard.

Unfortunately, we Musers have little opportunity to say anything that doesn’t fall into a narrow set of multiple-choice queries. Let’s take a little drive through the questions. Beware the speed bump.

Eyes on your own paper, buddy

Every Muse form I’ve filled out is essentially the same, with a few seasonal variants. (What is your favorite Halloween movie?) The Muse announces that some questions will be repeated every few months “so that we can see how your opinions change over time.” You could perhaps make the Muse happy providing different answers at each iteration of the survey.

The Muse’s first clutch of questions involves your opinion of movies in general. Do you like ‘em or dislike ‘em? Do you think they’re better than they were in the 1990s? How do they compare with other forms of entertainment, like TV shows, videogames, and music? Do you like indies, kid movies, dramas, comedies, animation, documentary, whatever? How often do you see movies in theatres, rent DVDs, buy DVDs, or watch a movie online? How do you like the moviegoing experience in your local theatre? And so on. This is all pretty banal and anodyne, though I can imagine a firm using these data to help back up production decisions. (“See? I told you nobody likes Westerns.”)

The Muse proffers the Don’t Know option often, sometimes to puzzling effect. Is Don’t know really an appropriate answer to statements like the following?

Movies are often a topic of conversation among my friends.

I like to watch my favorite movies over and over again.

I use a DVR, iPod, computer CD or DVD burner on a regular basis.

Sometimes the inquiry turns Borgesian. Here’s one statement:

Movie plots are more predictable than they used to be.

If you don’t know, they’re probably not more predictable, at least to you. Another question asks:

Did you know that some movie theaters offer programs for frequent moviegoers, where you can earn free popcorn, sodas, and movie tickets depending on how many times you go to the theater?

The options are: Yes/ No/ Don’t know. Presumably if you don’t know, you’ll answer No. But if you answer Don’t know, does that mean that you don’t know whether you know?

In any case, the speed bump comes up soon enough. Not to scare you, but maybe there’s some serious stuff ahead.

Don’t know what a slide rule is for

We’re eased into the hard questions gradually:

Are you aware of peer-to-peer file-sharing services that allow you to download full-length films or TV shows via the Internet for free?

Again we get Don’t know as an option, which isn’t really viable. Try telling an interrogator allowed to use harsh measures, I don’t know if I’m aware of peer-to-peer file-sharing services. . . But now there’s another option: Prefer not to say. Good choice. Too bad it won’t come up again.

We’re asked how often we download purchased movies and TV shows, download bootleg material, buy bootleg DVDs, copy DVD files to hard drives, and receive CD or DVD copies from a friend. The Muse is also curious about how often you copy such material to disc for a friend, or for your personal use. The permitted answers range from Never to 4 or more times a month. This menu may need revising; I suspect some of my friends pursue these activities 4 or more times an hour.

Anyhow, it seems likely that nearly everybody between the ages of 4 and 50 has done at least one of these things. You’d prefer to say Prefer not to say, but the only evasive tactic is Don’t know.

You recall the Perry Mason trick: After the sweating witness has testified, Perry asks, “Are you aware of the penalties for perjury?” Something similar happens here. Once the Muse establishes that you’ve surely broken the law, with relentless prosecutorial logic it asks if you did so willfully. Getting cozy in a Good Cop way, the Muse acquires a singular personal pronoun:

For each of the following activities, please tell me whether you think they are legal or illegal:

Copy a movie or TV show on a CD or DVD to give to someone else.

Go to a website and download a TV show you paid for.

Go to a website and download a full-length movie you paid for.

Copy files from DVDs onto your hard drive.

Buy a bootleg DVD.

Go to a file-sharing site and download a TV show for free.

Receive a copy of a movie or a TV show on a CD or DVD for your own use—to watch whenever you want.

But the statements are too bald and inexact. These activities aren’t necessarily illegal, according to intellectual property attorney Jim Peterson:

The work might be in the public domain (too old, registration or renewal failure) or it might be a fair use. You could conceivably download a movie as a fair use for your own scholarship without violating the DMCA prohibitions on defeating copy protection or removing copyright management information. The guy who cracked the copy protection on the DVD probably has some Digital Millennium Copyright Act problems, though. Same thing with buying a bootleg DVD. I don’t think buying is illegal; it’s selling that’s the problem.

Since the Muse’s questions don’t allow for such nuances, once more the Don’t know option is looking mighty attractive.

My Muse goes on to ask if any of the following considerations would affect your decision to undertake the illegal activities you’ve already mentioned. Now if you thought that they were all legal, or if you answered Don’t know, then presumably you don’t have to reply to what follows. In any case, imagine Penn Gillette reciting each of these possibilities in his most explosively disrespectful voice, with expletives freely inserted. Would you avoid breaking the law . . .

If official DVDs were $5 cheaper?

If tickets for the movie theater were $2 cheaper?

If a portion of the DVD price was contributed to charity?

If you were concerned that buying and downloading unofficial copies was tied to criminal activities or terrorism?

If friends or somebody in your community were being prosecuted for a similar activity?

If you received a notice warning you that you might be prosecuted?

If you got off with a wrist slap and a threat of future surveillance?

If you were made an example in order to deter other scum?

If specially-made DVDs carried an electrical charge of 50,000 volts to be shot into a user when s/he sought to copy them?

If certain DVDs were sprayed with microbes carrying sexually transmitted diseases?

Granted, I made up some of these, but maybe you can’t tell which ones. Anyhow, the correct answer is Don’t know, said quickly ten times with your hands over your ears.

Suppose you say you don’t download movies illegally. Then My Muse, not one to back off, asks why you don’t break the law. The lengthy set of options includes such noble justifications as I don’t have the time, I don’t know how to do it, I don’t like to watch movies at my computer, It takes too long, and I wouldn’t get the DVD bonus materials. For such freedoms brave men died.

The replies It is illegal and I’m afraid of getting prosecuted and sued come at the very end. Correct answer: Oh, riiight . . . It’s illegal. Sure . . . that’s it . . . Illegal. Of course, if the purpose of the questionnaire is not to find out what we think but to tell us what to think, then these questions come at the right moment. They tacitly say: All of the above-mentioned things you are doing, or are now thinking about doing, can be punished by lawsuits and a stay in the Big House.

The last page offers you a list of legal movie download sites, asking if you recognize or use any of them. I recognized most, but Guba and Vongo were new names to me. I don’t think I could bring myself to use any service, even for roto-rooting purposes, called Guba or Vongo.

Just as you’re ready to pack your toothbrush for the holding tank, the Muse gives a cheery farewell. “That’s it! . . .You’re done!”

When My Muse went online last year, industry observers noticed right away that the survey seemed more about selling people the MPAA’s line on copyright than about getting their responses. Anthony Kaufman, one of the dueling cavaliers of the cineblogosphere, wrote:

The leading questions are clearly part of a larger MPAA struggle to bolster copyright initiatives and crack down on fair use, file sharing and anything that threatens the bottom line of the international conglomerates. Dan Glickman may be the kinder, gentler face of the MPAA in the wake of Jack Valenti’s exit, but if his demeanor is softer, his goals are still just as nefarious.

This is a plausible interpretation. But I don’t want to rule out the possibility that the studios might really listen to my write-in request that they upgrade release prints and stick with 35mm instead of going digital. Or maybe the MPAA is branching out into online entertainment, like those commercials, quizzes, and snack-bar plugs that come up before the trailers. Is My Movie Muse a trial balloon for a new feature, DRM: Be Very Afraid?

Don’t know, Don’t know, Don’t know.

I’m not holding my breath for my Amazon certificate either.