Archive for February 2008

Pausing and chortling: A tribute to Bob Clampett

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery

Kristin here–

During my first year as a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the great animator Bob Clampett paid a visit to our campus. I actually got to sit next to him at lunch, and he was a charming, amusing man. Unfortunately I didn’t really know at the time what a genius he was, and, to my eternal regret, I neglected to ask for his autograph.

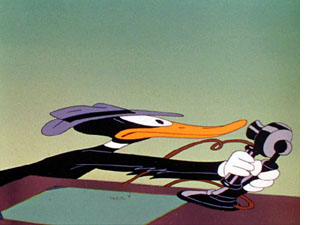

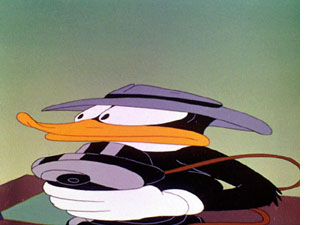

Today Clampett is less well-known to the general public than is Chuck Jones or Tex Avery. Jones and the other main creators of the classic Warner Bros.’s cartoons reportedly resented Clampett’s attempts to promote his own reputation by claiming sole credit for major achievements, such as “inventing” Bugs Bunny. When Jones put together The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie (1979), there were no Clampett-supervised cartoons included. Clampett never wrote his memoirs. Jones did and left Clampett out. (Below, Draftee Daffy, 1945.)

These three major directors had their own distinctive approaches. Jones was on the whole more cerebral and often opted for beautiful visuals, perhaps most obviously evident in What’s Opera, Doc. Avery had a penchant for bad puns, often assembling whole cartoons based entirely around them. Clampett went for craziness and often for break-neck speed. The Wikipedia entry on him has this to say: “his characters are easily the most rubbery and wacky of all the Warner directors’.” (Above, Baby Bottleneck [1946].)

That wackiness was built into the name of one of Warner’s two animated series, “Looney Tunes.” Daffy Duck’s name characterizes him, but modern audiences may not be aware that “Bugs” also was a slang term for “crazy.” Along with Porky Pig, those were the two characters that Clampett used most often.

I’m not going to sum up Clampett’s career here. There is already quite a bit of excellent material on him available on the internet. For an overview of his career and style, see Adrian Danks’s “It Can Happen Here! The World of Bob Clampett” on Senses of Cinema; Michael Barrier’s epic 1970 interview with Clampett, with comments and corrections, is available on his website. That website contains many other shorter pieces on Clampett. Danks and the Wikipedia entry both give enough bibliographical sources to direct enthusiasts to additional information.

My purpose here is more modest. I simply want to point out how to find even more hilarity in Clampett’s cartoons beyond simply watching them.

As I’ve mentioned, David and I are in the process of revising our second textbook, Film History: An Introduction. The other day I was working on the section that deals with Hollywood animation in the 1930 to 1945 period. We’re adding more color to the book for its third edition, so I decided that Draftee Daffy, which we describe briefly, should have its own color plate.

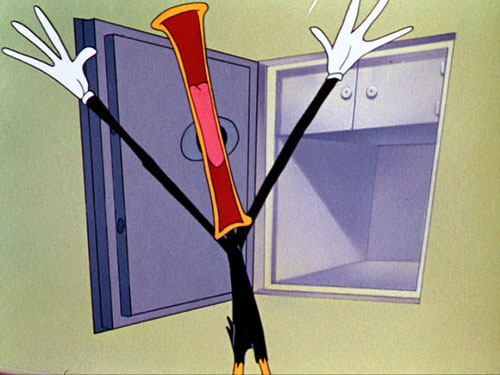

As I watched the film on DVD, I paused on a number of possible frames to use, and I found myself laughing out loud at almost every one—something that doesn’t often happen during the revision of a textbook. Some of the character movements in Clampett’s films are so fast and brief that they come across as a flurry of images too fleeting to register. Frozen, they reveal some of the extraordinary means that the director and his animators used to achieve those effects of speed. Clampett was also adept at highly exaggerated reactions and hilarious distortions of the animal body. Watching these cartoons with a finger on the pause button can yield hilarity and teach you a lot about normally hidden aspects of the art of animation.

David has written about the artistry in Walt Disney’s films. He points out that a quick movement may be accomplished by adding extra limbs, as when in Melody Time Johnny Appleseed gathers an armload of falling apples and multiple arms and hands convey the speed of his gestures—as do a pair of phantom heads in the uppermost frame of the three David reproduces.

Such multiple images work without our noticing them. It’s not an obvious sort of technique to use. As David wrote, “Through trial and error Disney’s animators learned that rather strange single images will look exactly right on the screen; these men were practical perceptual psychologists.”

The same was true in the Warners animation department. In The Big Snooze (1946), Clampett’s last cartoon for the studio, he includes a scene of Bugs rapidly tying Elmer to some railroad tracks. In a couple of frames, he sprouts extra arms and hands. In The Great Piggy Bank Robbery (1946), phantom images of Daffy accompany his firing a machine gun.

But Clampett’s single images were often far stranger than the ones in the Melody Time example. In this one from Draftee Daffy, for example, the extra figures of Daffy as he frantically builds a wall between himself and his nemesis (the little man from the draft board) are purple.

I suppose that’s because multiple black figures of Daffy would blend together, but it’s still a bit weird. As an animator, how do you decide on a color?

Maybe it’s because purple is a subdued color that won’t call attention to the extra ducks and yet will contrast well with the black. It’s also the same color as the floor, so that might create an extra reason why we won’t notice them as standing out from the overall composition as it flashes past. If you know those purple ducks are there, you can just barely see them during normal projection. If you don’t know that, then you’re likely to miss them.

(I used that example of Daffy building the wall in my sole academic publication on animation, “Implications of the Cel Animation Technique,” in Teresa de Lauretis and Stephen Heath, eds., The Cinematic Apparatus [St. Martin’s Press, 1980]. There it had to be in black and white, unfortunately.)

Clampett often draws upon a standard animation device, “stretch,” to convey a sense of speed–although his characters may cross a room in as little as two or three frames. The first image of the telephone scene from The Great Piggy Bank Robbery is a fairly straightforward example of stretch, yet in the same scene, Daffy rapidly turning around uses the opposite technique, “squash.”

A similar technique which Clampett uses occasionally for a character about to launch into a rapid movement is a sort of squash with a perspective effect stretching the character toward the viewer, as in The Big Snooze when Bugs instructs Elmer to “Run this way.” (Bugs isn’t the only one who gets into drag in these cartoons.)

I’ve picked some of my favorite Clampett films, but many frames worth pausing on are to be found in others. With the Looney Tunes boxed sets still coming out, in five volumes to date, one can hunt out the Clampett films–though annoyingly, the indexes list neither the date nor the supervising animator, and there seems to be little logic involved in which films go on which discs. (There are also occasional jumps where something has presumably been censored.) It’s best to get thoroughly familiar with these films by simply viewing them. Then, pick up that remote and begin your search. You’ll discover that Clampett was one of the most imaginative of those “practical perceptual psychologists.”

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery.

Creating a classic, with a little help from your pirate friends

DB here:

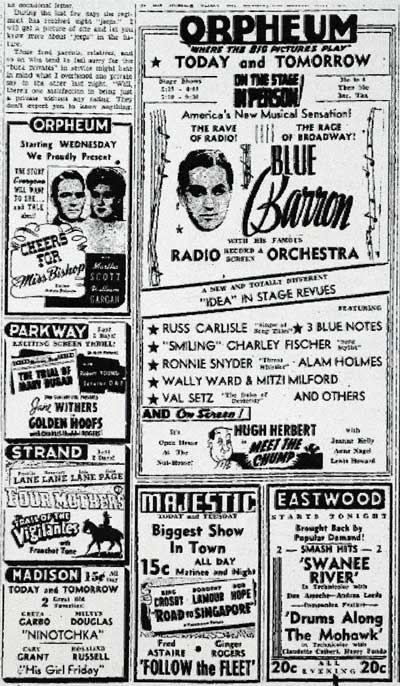

In early April of 1940, His Girl Friday came to Madison, Wisconsin. It ran opposite Juarez, The Light that Failed, Of Mice and Men, and a re-release of Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Pinocchio was about to open. Most screenings cost fifteen cents, or $2.21 in today’s currency.

Before television and home video, film was a disposable art. Except in big cities, a movie typically played a town for a few days. Programs changed two or three times a week, and double bills assured the public a spate of movies—nearly 700 in 1940 alone. People responded, going to the theatres on average 32 times per year. Given the competition, it’s no surprise that His Girl Friday didn’t stand out in the field; it was nominated for no Academy Awards and honored by no prizes. On just a single day in Madison, the cast of His Girl Friday was up against icons like Muni, Colman, March, and Bette Davis.

Nowadays, of course, nearly everyone regards HGF as one of the great accomplishments of the studio system. Most would consider it a better movie than any of the others it played opposite in my home town. A typical example of critical exuberance is Jim Emerson’s comment here. Or read James Harvey’s 1987 encomium:

It would be hard to overstate, I think, the boldness and brilliance of what Hawks has done here: not only an astonishingly funny comedy, but a fulfillment of a whole tradition of comedy—the ur-text of the tough comedy appropriated fully and seamlessly to the spirit and style of screwball romance. His Girl Friday is not only a triumph, but a revelation.

Oddly, this extraordinary film lay largely unnoticed for three decades. How did it become a classic? The answer has partly to do with the rising status of Howard Hawks, the director, among critics. It also owes something to changes in how academics thought about film history. And a little movie piracy didn’t hurt.

An unseen power watches over the Morning Post

Hawks the Artist is a creation of the 1960s. Before that, American film historians almost completely ignored him. Andrew Sarris often reminds us that he’s absent from Lewis Jacobs’ Rise of the American Film (1939), but he’s also missing from Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957), the most popular survey history of its day. Apart from press releases and reviews of individual films, there were few discussions of Hawks in American newspapers and magazines. The most famous piece is probably Manny Farber’s “Underground Movies” of 1957, which treats Hawks along with other hard-boiled directors like Wellman and Mann.

From the start, Hawks was more appreciated in France. There film historians acknowledged A Girl in Every Port (1928), in part because of the presence of Louise Brooks, and they usually flagged Scarface (1932) as well, which they could see and Americans couldn’t. (Howard Hughes kept it out of circulation for decades.) But Hawks is barely mentioned in Georges Sadoul’s one-volume Histoire du cinéma mondiale (orig. 1949) and he’s ignored in the 1939-1945 volume of René Jeanne and Charles Ford’s monumentally monotonous Histoire encyclopédique du cinéma (1958).

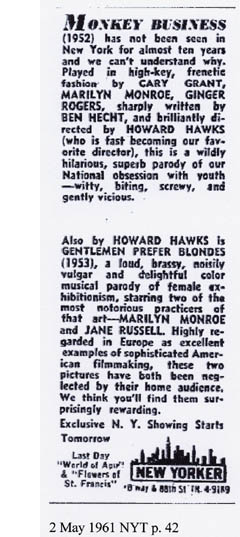

The essay that marked the first phase of reevaulation was evidently Jacques Rivette’s “The Genius of Howard Hawks” in Cahiers du cinéma in 1953. Inspired by Monkey Business, Rivette’s philosophical flights and you-see-it-or-you-don’t tone helped define the auteur tactics identified with Cahiers’s young Turks. Rivette and his colleagues became known as “Hitchcocko-Hawksians.” The essay, however, doesn’t seem to have been immediately influential. Antoine de Baecque claims that within Cahiers, an admiration for Hawks was controversial in a way that liking Hitchcock was not. (1) It took some years for Hawks to ascend to the Pantheon.

The story of that ascent has been well-told by Peter Wollen in his essay, “Who the Hell Is Howard Hawks?” In France, the Young Turks’ tastes had been nurtured by Henri Langlois, who showed many Hawks films at the Cinémathèque Française. In New York, Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer had become intrigued by Cahiers but were ashamed that as Americans they didn’t know Hawks’ work. They persuaded Daniel Talbot to show a dozen Hawks films at his New Yorker Theatre during the first eight months of 1961. The screenings’ success allowed Peter Bogdanovich to convince people at the Museum of Modern Art to arrange a 27-film retrospective for the spring of 1962. The package went on to London and Paris, sowing publications in its wake.

The story of that ascent has been well-told by Peter Wollen in his essay, “Who the Hell Is Howard Hawks?” In France, the Young Turks’ tastes had been nurtured by Henri Langlois, who showed many Hawks films at the Cinémathèque Française. In New York, Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer had become intrigued by Cahiers but were ashamed that as Americans they didn’t know Hawks’ work. They persuaded Daniel Talbot to show a dozen Hawks films at his New Yorker Theatre during the first eight months of 1961. The screenings’ success allowed Peter Bogdanovich to convince people at the Museum of Modern Art to arrange a 27-film retrospective for the spring of 1962. The package went on to London and Paris, sowing publications in its wake.

For the MoMA retrospective, Hawks granted Bogdanovich a monograph-length interview, which was to be endlessly reprinted and quoted in the years to come. (2) Sarris, now knowing who the hell Hawks was, wrote a career overview for the little magazine, The New York Film Bulletin, and this piece became a two-part essay in the British journal Films and Filming. Both Bogdanovich and Sarris made brief reference to His Girl Friday, as did Peter John Dyer in another 1962 essay, this one for Sight and Sound. At the end of 1962, another British magazine, Movie, published an issue on Hawks. At the start of 1963, Cahiers devoted an issue to him, including an homage by Langlois himself. Thanks to the work of Archer, Bogdanovich, Sarris, and MoMA, Hawks was rediscovered.

Sarris provided a condensed case for Hawks in his far-reaching catalogue of American directors, published as an entire issue of Film Culture in spring of 1963. There followed an interview with Hawks’s female performers in the California journal Cinema (late 1963), an appreciation by Lee Russell (aka Peter Wollen) in New Left Review (1964), another Cahiers issue (November 1964), J. C. Missiaen’s slim French volume Howard Hawks (1966), Robin Wood’s Howard Hawks (1968), and Manny Farber’s Artforum essay (1969). There were doubtless other publications and events that I never learned about or have forgotten. In any case, by the time I started grad school in 1970, if you were a film lover, you were clued in to Hawks, and you argued with the benighted souls who preferred Huston. . . even if you hadn’t seen His Girl Friday.

Light up with Hildy Johnson

One of my obsessions in graduate school was the close analysis of films. But I was also interested in whether one could build generalizations out of those analyses. My initial thinking ran along art-historical lines. My Ph. D. thesis on French Impressionist cinema sought to put the idea of a cinematic group style on a firmer footing, through close description and the tagging of characteristic techniques. But that approach came to seem superficial. I wasn’t satisfied with my dissertation; although it probably captured the filmmakers’ shared conceptions and stylistic choices, I couldn’t offer a very dynamic or principled account of formal continuity or change.

Watch a bunch of movies. Can you disengage not only recurring themes and techniques, but principles of construction that filmmakers seem to be following, if only by intuition? As I was finishing my dissertation, reading Russian Formalist literary theory pushed me toward the idea that artists accept, revise, or reject traditional systems of expression. These become tacit norms for what works on audiences. My reading of E. H. Gombrich pushed me further along this path. We should, I thought, be able to make explicit some of those norms. Eventually I would call this perspective a poetics of cinema.

I was assembling my own version of some ideas that were circulating at the time. In the early 1970s, several theorists floated the idea that different traditions fostered different approaches to filmic storytelling. People were seeing more experimental and “underground” work, as well as films from Asia and what was then called the Third World. Being exposed to such alternative traditions helped wake us up to the norms we took for granted. The mainstream movie, typified by what Godard called “Hollywood-Mosfilm,” seemed more and more an arbitrary construction.

People began examining films not as masterworks or as expressions of an auteur, but as instances of a representational regime. Films became “tutor-texts,” specimens of formal strategies that were at play across genres, studios, periods, and directors. Again, the French pointed the way, particularly Raymond Bellour, Thierry Kuntzel, and Marie-Claire Ropars. At the same moment, Barthes’ S/z was published in English, and it seemed to provide a model for how one might unpick the various strands of a text, either literary or cinematic. Screen magazine was a conduit for many of these ideas in the English-speaking world.

Some of my contemporaries disdained the mainstream cinema and moved toward experimental or engaged cinema. Others read the dominant cinema symptomatically, for the ways it revealed the contradictions of ideology. I learned from both approaches, but I believed that the current analysis of how Hollywood worked, even considered as a malevolent machine, was incomplete. Could we come up with a more comprehensive and nuanced account of the mainstream movie? This line of thinking was already apparent in non-evaluative studies of form and style, such as essays by Thomas Elsaesser, Marshall Deutelbaum, and Alan Williams. (3)

At some point in graduate school at the University of Iowa, between fall 1970 and spring 1973, I saw a screening of His Girl Friday. I fell in love with its heedless energy. It seemed to me a perfect example of what Hollywood could do.

In my admiration I was channeling the cultists. Rivette, in a review of Land of the Pharoahs: “Hawks incarnates the classical American cinema.” (4) Bogdanovich: He is “probably the most typical American director of all.” Richard Griffith, then film curator of MoMA, had slighted Hawks in his addendum to Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, but in his foreword to the Bogdanovich interview he caved to the younger generation: “Hawks works cleanly and simply in the classical American cinematic tradition, without appliquéd aesthetic curlicues.” As for HGF, in the 1963 Cahiers tribute Louis Marcorelles called it “the American film par excellence.”

Praising Hawks, and HGF specifically, was part of a larger Cahiers strategy to validate the sound cinema as fulfilling the mission of film as an art. What traditional critics would have considered theatrical and uncinematic in HGF—confinement to a few rooms, constant talk, an unassertive camera style—exactly fit the style that Bazin and his younger colleagues championed. (For more on that argument, see Chapter 3 of my On the History of Film Style.)

These niceties didn’t inform my reaction at the time. I was already primed to like Hawks, though, having caught what films I could after reading Wood et al. (During my initial summer in Iowa City, I went to a kiddie matinee of El Dorado and got Nehi Orange spilled down my neck.) On my first viewing His Girl Friday delighted me with the sheer gusto of the pace and playing. Clearly the cast was having fun. A press release sent out before the film claimed that during one scene, with Cary Grant dictating frantically to Rosalind Russell, she cracked him up by handing over what she had typed.

Cary Grant is a ham. Cary Grant is a ham. Now is the time for all good men to quit mugging. You don’t think you can steal this scene, do you—you overgrown Mickey Rooney? The quick brown fox jumps over the studio. Cary Grant is a ham.

Even discounting this tale as PR flackery, we know from Todd McCarthy’s excellent biography that Hawks encouraged competitive scene stealing and wily improvisation. Russell hired an advertising copywriter to compose quips she could “spontaneously” conjure up in her duels with Grant.

If there was a “classical Hollywood cinema”—a phrase that was in the early ’70s coming into circulation via Screen—the buoyant forcefulness of His Girl Friday embodied it. Here was a film pleasure-machine that hummed with almost frightening precision. What else do you expect from a director who studied engineering and whose middle name is Winchester?

Production for use

When I saw His Girl Friday, little had been written about it. Despite Langlois’ screenings, before the 1962 touring program, the Cahiers critics seemed to have had limited access to Hawks’ prewar work. His Girl Friday wasn’t released theatrically in France until January of 1945 (not perhaps the most propitious moment), and it apparently made no long-lasting impression on the intelligentsia. I can’t find any critical commentary on it in French writing before the 1963 issue of Cahiers.

In the United States, HGF earned Hawks a courteous write-up in the New York Times by, of all people, Bosley Crowther, (5) but it wasn’t acknowledged as an instant classic like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington or The Philadelphia Story. After the initial flurry of mostly favorable reviews, the movie seems to have been forgotten until Manny Farber’s 1957 essay, and even there it’s only mentioned in a list. Interestingly, it wasn’t screened during the 1961 New Yorker series. Robin Wood’s sympathetic but not uncritical discussion in his Hawks book of 1968 seems to have been the most comprehensive account available since the movie’s release.

At about the time Wood’s book was published, something big happened. Columbia Pictures failed to renew its copyright, and His Girl Friday fell into the public domain.

Entrepreneurs made dupe copies, in quality ranging from okay to terrible. You could rent one for peanuts and buy one for only a little more. Some of these bleary prints have been telecined and turned into the DVD versions of the film that fill bargain bins today. After I got to the University of Wisconsin, where Hawks films stoked the two dozen campus film societies, I bought a public domain print. The copy was better than average, although it lacked the fairy-tale warning title at the start. From 1974 on, I showed the poor thing constantly.

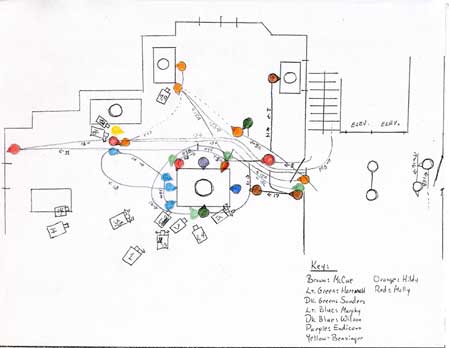

In Introduction to Film, taught to hundreds of students each semester, HGF illustrated some basic principles of classical studio construction. It had the characteristic double plotline (work/ romance), a careful layout of space, an alternation of long takes and quick cutting, manipulation of point-of-view, judicious depth framing (see frame below), and cascading deadlines. In Critical Film Analysis, I asked students to map out scenes shot by shot (see diagram above) and to show how different approaches (genre-based, feminist, Marxist) would interpret the film. In a seminar on “the classical film and modernist alternatives” HGF grounded comparisons with Bresson, Dreyer, Ozu, Godard, and Straub/Huillet. By steeping ourselves in such alternative traditions, could we resist the naturalness of Hollywood artifice?

The movie became a UW staple. It went into the first edition of Film Art (1979) as an instance of classical construction; even the telephones were scrutinized. Marilyn Campbell’s paper from our seminar was published in 1976. (6) Over the years, many of our grad students, exposed to the film in our courses, have gone on to use it in their teaching.

Doesn’t have to rhyme

I can’t let HGF go. I still use moments to illustrate points in my writing and lectures. Madison colleagues and I swap banter from it; Kristin and I talk in Hawks-code, as she explains here. I’ve been told that grad students in another PhD program compared our program to the Morning Post pressroom (favorably or not, I don’t know). Thanks to Lea Jacobs, the invitation to my retirement party was surmounted by a picture of Walter Burns whinnying into his phone.

But seriously, His Girl Friday, isn’t a bad guide to a lot of social life. You can learn a lot from its Jonsonian glee in selfishness and petty incompetence, as well as its sense that virtue resides with the person who has the fastest comeback. Think as well how often you can use this line in a university setting:

If he wasn’t crazy before, he would be after ten of those babies got through psychoanalyzing him.

I’m not claiming special credit for the HGF revival, of course. Plenty of other baby-boomer film professors were teaching it. It became a reference point for feminist film criticism, particularly Molly Haskell’s From Reverence to Rape (1974), and it has never lost its auteurist cachet. Richard Corliss’s 1973 book on American screenwriters flatly declared that “His Girl Friday is Hawks’s best comedy, and quite possibly his best film.”

Most important of all, TV stations were screening their bootleg prints. HGF didn’t become a perennial like that other public domain classic It’s a Wonderful Life, but its reputation rose. Its availability pushed the official Cahiers/ Movie masterpieces Monkey Business and Man’s Favorite Sport? into a lower rank, where in my view they belong.

Once HGF became famous, the proliferation of shoddy prints became an embarrassment. In 1993 it was inducted into the National Film Registry, which gave it priority for Library of Congress preservation. Columbia managed to copyright a new version of the film. A handsomely restored version was released on DVD, and a few years back I saw a 35mm copy whose sparkling beauty takes your breath away.

The lesson that sticks with me is this. If Columbia had renewed its copyright on schedule, would this film be so widely admired today? Scholars and the public discovered a masterpiece because they had virtually untrammeled access to it, and perhaps its gray-market status supplied an extra thrill. Thanks mainly to piracy, His Girl Friday was propelled into the canon.

Epilogue

In May of 1940, His Girl Friday hung around Madison, shifting from its first venue, the Strand downtown, to an east side screen, the Madison. The film came back in late September to yet a third screen, the Eastwood (now a music venue).

HGF was revived in March of 1941, as the second half of a double bill at the Madison (bottom left below). Check out the competition: some killer re-releases from Ford, Lubitsch, Astaire-Rogers, and Hope-Crosby. A Midwestern city of 60,000 could become its own cinémathèque without knowing it.

(1) Antoine de Baecque, Cahiers du cinéma: Histoire d’une revue, vol. 1: À l’assaut du cinéma, 1951-1959 (Paris: Cahiers du cinéma, 1991), 202-204.

(2) Bogdanovich has published a much fuller version in Who the Devil Made It? (New York: Knopf, 1997) , 244-378.

(3) Thomas Elsaesser, “Why Hollywood?” Monogram no. 1 (April 1971), 2-10; “Tales of Sound and Fury,” Monogram no. 4 (1972), 2-15; Marshall Deutelbaum, “The Structure of the Studio Picture,” Monogram no. 4 (1972), 33-37; Alan Williams, “Narrative Patterns in Only Angels Have Wings,” Quarterly Review of Film Studies 1, 4 (November 1976), 357-372.

(4) Jacques Rivette, “Après Agesilas,” Cahiers du cinéma no. 53 (December 1955), 41.

(5) Bosley Crowther, “Treatise on Hawks,” New York Times (17 December 1939), 126. “He brings to his work as a director the ingenious and calculating brain of a mechanical expert. . . . He pitches into the job just as though he were building a racing airplane.”

(6) Marilyn Campbell, “His Girl Friday: Production for Use,” Wide Angle 1, 2 (Summer 1976), 22-27.

For a helpful collection of conversations with the master, see Howard Hawks Interviews, ed. Scott Breivold (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2006). Go here for a 1970s piece by James Monaco on then-current controversies.

PS 24 Feb: Jason Mittell responds to my post with some nice nuancing and draws out the implication for copyright issues: contrary to current media policy, the wider availability of a work can actually enhance its value.

Coming attraction: Kristin is preparing a blog entry commenting on fair use in the digital age.

Hands (and faces) across the table

DB here:

In books and blogs, I’ve expressed the wish that today’s American filmmakers would widen their range of creative choices. From the 1910s to the 1960s (and sometimes beyond), US filmmakers cultivated a range of expressive options—not only cutting and camera movement but other possibilities too. Studio directors were particularly adept at ensemble staging, shifting the actors around the set as the scene develops.

You can still find this technique in movies from Europe and Asia, as I try to show in Figures Traced in Light and elsewhere on this site. But it’s rare to find an American ready to keep the camera still and steady and to let the actors sculpt the action in continuous time, saving the cuts to underscore a pivot or heightening of the drama. Now nearly every American filmmaker is inclined to frame close, cut fast, and track that camera endlessly. I’ve called this stylistic paradigm intensified continuity.

As Los Angeles agent and former editor Larry Mirisch once put it in conversation with me: “They used to move their actors; now they move the camera.” Most of today’s prominent directors prefer kinetic camerawork and machine-gun cutting. This tends to make their staging rather simple and static: we get stand-and-deliver or walk-and-talk (subject of a blog entry here).

The result is a split in contemporary American style. Action scenes are often gracefully and forcefully choreographed (though sometimes the editing fuzzes up character position and overall geography). By contrast, conversation scenes, which could be choreographed as well, are handled either as a Steadicam walk-and-talk or simply as seated actors talking to one another, with cuts breaking up the lines and the camera on the prowl. (I discuss some examples in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 128-173.) (1) You sometimes suspect that today’s directors are most at home shooting lots of people hunched over workstations, making the principal form of suspense a LOADING command.

Don’t get me wrong. Like all styles, intensified continuity isn’t a bankrupt option; many fine directors, from the Coens to Michael Mann, have worked vigorous variants on it. What I’m arguing for is more plurality, more tones in the director’s palette. I’ve revived these cranky ideas in discussing a single shot, this time in Variety. Today’s blog entry expands on that brief piece, so you may want to hop over to it here before reading what follows.

Directing us

One task facing any director is to direct—not only actors but us. The filmmaker must direct our attention to what’s important for responding to the drama at any moment. Since the late 1910s, we’ve known that close-ups and frequent cutting do just that. Tight framings and rapid cuts can steer the audience’s attention through a scene. So the question becomes: How can you direct attention without using close views and fast cutting?

Well, for one thing you can place the main action in the center of the picture format. If there are several points of interest in the shot, which is usually the case, you can arrange them symmetrically around the central zone of the shot—in film, usually an zone just above the geometrical center of the picture format. You can also position your main players so that the most important ones are closer and/or facing toward the camera. By turning a character away from the camera, you can drive the audience’s eye to someone else. There are other pictorial cues worth mentioning (lighting, color combinations, patterns in the set design), but these will hold us for now. Add in movement—characters shifting their position, especially coming closer to the camera—and you have a suite of cues that a film shot can provide.

Apart from these purely compositional factors, you the director can exploit some cues that are part of our social proclivities. When we watch other people, we’re attracted to areas of high information—which, for creatures like us, are faces and hands. Faces send signals about what people are thinking and feeling, with the areas around the eyes and mouth telling us most. Hands are the source of gestures, as well as potential threats. And of course if someone is speaking and others are listening, we are likely, all other things being equal, to look at the speaker.

The crucial fact is that in ensemble staging all these cues, and more, are at work at the same time. The director’s skill is orchestrating them so that they support one another, guiding us to see this or that. (On rare occasions, the director will use them to misguide us, but let’s stick with the default for the moment.) For a long time, filmmakers knew intuitively how to coordinate these cues to create rich and intricate shots; I fear that they no longer know how. (2)

That’s what makes one passage in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood of interest to me. The scene presents Paul Sunday explaining to Daniel Plainview that there’s oil on his family’s property. Daniel and Paul are bent over a map on a tabletop, with Daniel’s assistant Fletcher Hamilton and Daniel’s son HW watching. The scene is presented in a single shot, with a slight camera movement forward at the start.

The composition could hardly be simpler: four people lined up, three at the edge of the table. The heads cluster around the center of the format, with HW lower and off-center; no surprise that he’s the least important character in the scene (though his question to Paul foreshadows action in the film to come). Paul is explaining where the oil is, and the two men’s faces and hands command our attention as they speak.

Many directors would have cut in to a close-up of the map, showing us the details of the layout, but that isn’t important for what Anderson is interested in. The actual geography of Plainview’s territorial imperative isn’t explored much in the movie, which is more centrally about physical effort and commercial stratagems.

Questioning Paul about his family, Daniel turns slightly away. This clears a moment for HW to ask about the girls in Paul’s family, and for a moment our attention is steered to the right, to pick up their interchange.

Then Fletcher asks about the farm, and as Paul and Daniel tilt their faces to him, he earns his place in the center of the frame. Before, when we could see the faces of the two men closest to the camera, he was subsidiary, but now he becomes salient. On the left, Daniel shifts away uneasily, turning almost completely away from the camera. In answering Fletcher, Paul turns away in the opposite direction, as if shy or guilty; his awkward gesture of stroking his hat seems to confirm Daniel’s doubts about him.

During a pause, Paul turns back to stare directly at Daniel, saying quietly, “The oil is there.” At the same time, Daniel, still turned away, is exchanging a glance with Fletcher. At this point, Anderson’s training of us pays off: we’re ready to detect the slight shift in Fletcher’s eyes, which confirms that Daniel’s looking at him. “Watch their eyes,” as John Ford liked to say.

Paul sets out to leave, and he refuses the invitation to stay the night. At this point comes the scene’s biggest gesture. Daniel raises his hand, in the dead center of the frame.

Spreading his long, thin fingers, Daniel commands our attention. He seems at once to be halting the young man and threatening him. But the gesture becomes the prelude to a handshake. Daniel’s characteristic blend of bluff assurance, friendliness, and aggressiveness are packed into this single gesture. (At the climax, other gestures will recall this one.)

Daniel steps closer to Paul, blocking out Fletcher, to make his threat: If he travels so far and doesn’t find oil, he’ll find Paul and “take more than my money back.” Paul agrees and moves away. “Nice luck to you, and God bless.”

The men watch Paul leave the building. End of scene.

Without any close-ups or cutting, Anderson has skillfully steered us to the main points of the scene, which are carried by the performers. The drama builds through small changes of position, shifts of weight, and facial expressions that accompany the dialogue. (The somber, plaintive music adds an uneasy edge.) Daniel seems more threatening when we don’t see his reaction, and Anderson’s camera forces us to scrutinize Paul’s expressions and body language for signs that this is a scam. It takes confidence to make a raised hand the climax of a scene, but the gesture gains its force by being the most aggressive moment in an arc of quietly accumulating tension.

All the principles involved here—frontality, spacing of figures, slight shifts of compositional focus, actors’ body language—are simple in themselves, but they gain a strong impact by cooperating with one another. The scene’s quiet obliqueness is characteristic of the film, which, at least until the last few minutes, carries us along with hints about where the action might go and what drives its characters.

Yet simplicity shouldn’t imply simplification. Anderson’s willingness to give the shot several points of interest, some more stressed than others, creates an understated tension. The shot’s gravity stems from its conciseness, a quality that Anderson admires in 1940s studio films like The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

Two more tabletops

The staging strategies Anderson uses aren’t new, as I’ve suggested. They’re part of the history of film as an art form, and many directors have continually relied on them. I don’t think that this is always a matter of influence, although surely filmmakers learned from watching earlier films. Often, directors working within similar constraints intuitively rediscover what other directors have already done.

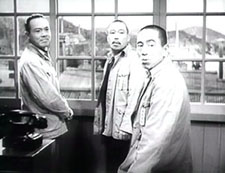

Consider this scene from Kurosawa Akira’s The Most Beautiful (1944). The setting is a plant where Japanese workers, mostly girls and women, are manufacturing bombsights. The workers have vowed to increase production for the war effort, and they are working to the point of exhaustion. The plant supervisors are worried that the pace will take its toll on the girls.

The scene starts with the eldest supervisor studying the output chart, lying on a table below the frame edge. His colleagues are turned away, at the window. He is the one who must decide how to keep the girls healthy and the output steady. The table and the window will be the two poles of the action, and the actors will oscillate between them. The process starts when the eldest retreats to the window, and one comes forward to study the report.

He’s followed by his opposite number, and they echo one other in rubbing their necks. They’re as tired as the assembly-line girls. Their superior turns and says that there’s no point in lowering the quota because the girls are so devoted that they’d push harder anyway.

The men have turned to listen to him, driving our attention to his centered, frontal figure. After the elder has turned away again, the man on the right says that this might be the critical juncture. Remarkably, all three men remain turned from us, creating a slight pictorial tension.

This tension is extended when the supervisor on the left states his confidence in the children, their team leader, and their teacher. This makes the eldest turn around.

The speaker walks to the window, arguing that the girls will succeed, but the leader turns away again dubiously. He doesn’t offer a decision because an offscreen voice announces that a teacher has come to see them, and they all turn to look.

The factory’s problem isn’t solved; the seesawing of the staging has presented that irresolution dynamically. In a single shot, the difficulty of the administrative decision has been expressed in counterweighted movements in and out, by the figures’ frontality and dorsality. Again, it can seem simple, but where a contemporary American director would have given us a prolonged passage of stand and deliver, with intercut close-ups, Kurosawa has created a little ballet out of the men’s uncertainties. Like Daniel’s raised hand, but with even less emphasis, the assistant’s plea on behalf of the girls’ commitment has gained a subtle prominence. Yet all he has done is walk to the window.

I’m not saying, of course, that Anderson took the idea from Kurosawa. Given the initial choice to stage the scene behind a table, and the inclination to present the action in one shot, both directors spontaneously drew on basic staging principles. This is what film directors have always done. So as a finisher, here’s one last tabletop interlude from Cecil B. DeMille’s Kindling (1915). The entire scene is a dense and intricate affair, but let’s pick just one moment. Maggie has become a servant to a rich woman, Mrs. Burke-Smith, and she’s about to be arrested for theft. Detective Rafferty is ready to handcuff her, but Mrs. Burke-Smith changes her mind.

DeMille arranges his actors so that we can’t miss the rich woman’s moment of decision. She is in the foreground, and her face is in the upper center of the frame. The other actors are blocked, so that her expression is the only one we can see clearly at the crucial moment. Her hand gesture, stretching across the central axis of the frame, confirms that she won’t charge Maggie. (For a similar use of “blossoming” actors’ movements in 1910s cinema, go here and look at Figs. 2A10-2A11.) What DeMille knew, Kurosawa discovered afresh, and Anderson hit upon it again.

Strategies of staging, like other principles shaping how films tell stories, lie behind each concrete creative decision the film artist makes. They run as undercurrents through film history, almost never discussed by critics. They form a body of tacit knowledge, flowing across our usual distinctions of period, genre, director, national cinema. We can trace continuities and changes, examining how the strategies are revived, revised, or rejected. They can provide us with subtle but powerful experiences. They constitute a skill set that is available to filmmakers today. . . if any will, like Anderson, seize the chance.

(1) True, Wes Anderson keeps the camera still, but in his frontal, family-portrait framings the cutting and line readings do all the work; dynamic staging isn’t on his menu.

(2) I survey the development of these and other tactics in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style. On this site, for one example go here and scroll down to the Bauer material.

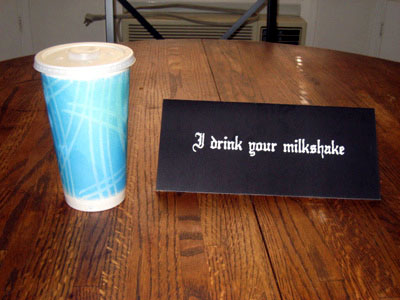

I drink your Oscar promo

Kristin here–

A week or so ago, David and I were watching Keith Olbermann’s “Countdown” on MSNBC. As the tagline to one of the stories, Keith quoted, “I drink your milkshake!” David was puzzled and asked why that sentence was suddenly popping up all over the place. I reminded him that Daniel Plainview says that line in the final scene of There Will Be Blood—a film that both of us like very much. That was when I learned that “I drink your milkshake” had entered the buzz of pop culture.

On Saturday, February 9, the new Entertainment Weekly arrived, with a half-page story, “Shake, Shake, Shake,” by Gregory Kirschling, dealing with the milkshake-line phenomenon. (The piece doesn’t seem to be online yet.) Kirschling calls it “one of the strangest exclamations of film history.”

Why so very strange? Odd, maybe, but it makes perfect sense in context. It comes in the film’s final scene, set in the bowling alley of Daniel’s mansion. Naive preacher Eli Sunday has just told Daniel that he should buy a last bit of oil-rich land, whose owner had earlier refused to sell. Daniel replies that he has already extracted the oil from that plot.

The Milkshake Dialogue [Spoilers Ahead!]

Eli brings drinks and sits with Daniel near the bowling lanes, saying, “Mr. Bandy has passed on to the Lord.” He adds that William, Bandy’s grandson, wants to be an actor in Hollywood. Eli offers to help Daniel negotiate with William concerning the land: “Daniel, I’m asking if you’d like to have business with the Church of the Third Revelation in developing this lease on young Bandy’s thousand-acre tract. I’m offering you to drill on one of the great undeveloped fields of Little Boston.”

Daniel replies, “I’d be happy to work with you.” But he adds a condition: Eli must state that he is a false prophet and that God is a superstition. After receiving Daniel’s apparent agreement to financial terms, Eli reluctantly makes these statements over and over as Daniel insists that he speak more forcefully.

After Eli’s declaration, Daniel declares abruptly, “Those areas have been drilled.”

Eli, baffled, murmurs, “What?”

Daniel repeats, “Those areas have been drilled.”

Eli, as before: “No, they haven’t.”

Daniel: “Yes. It’s called drainage, Eli. See, I own everything around it, so, of course, I get what’s underneath it.”

Eli: “But there are no derricks there. This is the Bandy tract. Do you understand?”

Daniel: “Do you understand, Eli? That’s more to the point. Do you understand? I drink you water. I drink it up. Every day, I drink the blood of lamb [or land?] from Bandy’s tract.”

At this point Eli confesses how desperate he is, having sinned and lost his investments. Daniel taunts him viciously, saying that Eli’s twin brother Paul was the chosen one, having taken the $10,000 that Daniel had given him and started a small but successful oil company as a result. (The actual amount handed over in the one scene in which Paul appears was $500.)

Reverting to the subject of the Bandy tract, Daniel continues, “That land has been had. There’s nothing you can do about it. It’s gone. It’s had.”

Eli: “If you would just—“

Daniel, loudly, drooling: “Drainage! Drainage! Eli, you boy. Drained dry. I’m so sorry. If you have a milkshake and I have a milkshake—there it is. [He holds up his index finger]. That’s the straw, you see. [He turns and walks away from Eli] And my straw reaches acrooooooossssss [walking back toward Eli] the room … I … drink … your … milkshake. [He makes a sucking noise] I drink it up!”

Eli: “Don’t bully me, Daniel.”

At this point Daniel throws Eli down, begins hurling bowling balls and pins at him, and finally beats him to death.

The milkshake analogy isn’t all that bizarre. Daniel choses a metaphor for drainage that he thinks Eli can understand.

Beyond that, the milkshake speech is a way of emphasizing Daniel’s delight, not just in making a fortune in the oil business, but in doing so by paying little, or in this case no, money to those whose land he exploits. Stealing someone’s milkshake is a petty form of theft, so Daniel is able to trivialize the removal of oil that Eli has been counting on as his last chance for financial and spiritual salvation. The taunting also allows Daniel to revenge himself for the parallel earlier scene in the church where Eli had forced him repeatedly to confess how he had betrayed his own son. In this final portion of the film, Daniel no longer has any need to put on a friendly face, to pretend to have empathy with others.

Daniel mentions drinking water as well. He’s eating a cold, leftover piece of meat during much of this, and Eli is drinking whiskey. Eating and drinking are common motifs in the film, with elaborate discussions of how the rocky land of the Sundays’ ranch produces no grain but only supports goats. Upon Daniel’s arrival there, the family can offer him no bread but only milk and potatoes.

Thus I don’t think the milkshake line is out of place. That portion of the scene is, however, as Kirschling says, “weird, vaguely hilarious, and unsettling.”

By the way, according to a story in USA Today, director Paul Thomas Anderson derived the dialogue from “a transcript he found of the 1924 congressional hearings over the Teapot Dome scandal.” Sen. Albert Fall described oil drainage thus: “Sir, if you have a milkshake and I have a milkshake and my straw reaches across the room, I’ll end up drinking your milkshake.” He was convicted of taking bribes for oil rights on public lands.

Blenderized by the Internet?

Kirschling points out that the speech has spread far indeed. There’s a YouTube video, “There Will Be Milkshakes,” by Kevin Koonz (spelled Kunze in the EW and USA Today stories). There’s a website, “I Drink Your Milkshake.com,” which started as just a posting of the line and became a forum for discussing the film. The USA Today article declares the line “Hollywood’s Hottest Catchphrase.” There are various designs of T-shirts available on Cafepress and eBay.

It does seem odd that a line from a film that is an art-house favorite, with under $25 million grossed in the U.S. to date, should spread so widely. But these things happen.

The phenomenon doesn’t stop there, though. On February 8, Variety blogger Kristopher Tapley revealed that he and a friend had received courier-delivered milkshakes with an accompanying promotional flyer for the film. (Presumably Tapley himself is to be credited with the photos above and below. The small print in the lower one reads, “From Your Friends at Paramount Vantage.”)

Upon reading Tapley’s entry, David’s first reaction was, “Where can I get one of those milkshakes?” (I doubt they get delivered here in flyover territory, but the Dairy State can provide its own fine milkshakes.) My first reaction was, “I wonder how soon one of those promo fliers will show up on eBay.” (So far, none has. Just the T-shirts.)

[Added February 12: Apparently there is a hierarchy among the recipients of the Paramount Vantage promo. Tapley specifies that his milkshake came hand-delivered. On February 8, Peter Sciretta posted on the /film site the news that he received the same brochure, but his contained a coupon for a free milkshake (shown in a picture in his entry). He also reveals the brand involved: Cold Stone Creamery.]

Kirschling’s EW piece deplores this sort of thing: “The ironic, Internet-fast catchphrasing of a movie as rich and serious as Blood—and a performance as emotional as Day-Lewis’—is more than a little depressing. It reduces art to a punchline; it puts an epic in a blender and comes out with … a milkshake.”

True, in a sense. But great art has always been subject to humorous treatment and tends to come through unscathed. Marcel Duchamp stuck a mustache on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa and put it in a museum, and the act is considered a daring stroke of avant-garde art. The 1941 comedy Hellzapoppin’ contains a gag about the Rosebud sled from Citizen Kane. There are innumerable examples. The internet has accelerated such of manipulation of artworks and made us more aware of them, but it’s not new—and it is inevitable.

Indeed, the creators of the film don’t seem to be terribly upset. Paramount Vantage obviously seized upon the publicity opportunities, ordering high-quality milkshakes delivered like so many “For your consideration” ads. The USA Today article refers to the director’s reaction: “Not that Anderson minds—or worries that it will undermine the gravitas of the movie, which is up for eight Oscars, including best picture, director and actor. ‘I love the YouTube video,’ he says. ‘It’s completely insane and hilarious. It’s crazy what people latch onto.’”

Anderson is no doubt being polite about the video. It’s a typical hastily made mashup with randomly edited images from a trailer juxtaposed with Kelis’ 2003 song “Milkshake.” As Kirschling remarks, “How original!” But you have to believe that as a result of all the fuss quite a few more people will get intrigued and go to see There Will Be Blood than would have otherwise. They’ll certainly have to sit through the whole thing before reaching the moment they came to savor. And, knowing all of the above, I still was able to re-watch that final scene and find it as chilling as it was the first time through.