Pausing and chortling: A tribute to Bob Clampett

Thursday | February 28, 2008 open printable version

open printable version

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery

Kristin here–

During my first year as a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the great animator Bob Clampett paid a visit to our campus. I actually got to sit next to him at lunch, and he was a charming, amusing man. Unfortunately I didn’t really know at the time what a genius he was, and, to my eternal regret, I neglected to ask for his autograph.

Today Clampett is less well-known to the general public than is Chuck Jones or Tex Avery. Jones and the other main creators of the classic Warner Bros.’s cartoons reportedly resented Clampett’s attempts to promote his own reputation by claiming sole credit for major achievements, such as “inventing” Bugs Bunny. When Jones put together The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie (1979), there were no Clampett-supervised cartoons included. Clampett never wrote his memoirs. Jones did and left Clampett out. (Below, Draftee Daffy, 1945.)

These three major directors had their own distinctive approaches. Jones was on the whole more cerebral and often opted for beautiful visuals, perhaps most obviously evident in What’s Opera, Doc. Avery had a penchant for bad puns, often assembling whole cartoons based entirely around them. Clampett went for craziness and often for break-neck speed. The Wikipedia entry on him has this to say: “his characters are easily the most rubbery and wacky of all the Warner directors’.” (Above, Baby Bottleneck [1946].)

That wackiness was built into the name of one of Warner’s two animated series, “Looney Tunes.” Daffy Duck’s name characterizes him, but modern audiences may not be aware that “Bugs” also was a slang term for “crazy.” Along with Porky Pig, those were the two characters that Clampett used most often.

I’m not going to sum up Clampett’s career here. There is already quite a bit of excellent material on him available on the internet. For an overview of his career and style, see Adrian Danks’s “It Can Happen Here! The World of Bob Clampett” on Senses of Cinema; Michael Barrier’s epic 1970 interview with Clampett, with comments and corrections, is available on his website. That website contains many other shorter pieces on Clampett. Danks and the Wikipedia entry both give enough bibliographical sources to direct enthusiasts to additional information.

My purpose here is more modest. I simply want to point out how to find even more hilarity in Clampett’s cartoons beyond simply watching them.

As I’ve mentioned, David and I are in the process of revising our second textbook, Film History: An Introduction. The other day I was working on the section that deals with Hollywood animation in the 1930 to 1945 period. We’re adding more color to the book for its third edition, so I decided that Draftee Daffy, which we describe briefly, should have its own color plate.

As I watched the film on DVD, I paused on a number of possible frames to use, and I found myself laughing out loud at almost every one—something that doesn’t often happen during the revision of a textbook. Some of the character movements in Clampett’s films are so fast and brief that they come across as a flurry of images too fleeting to register. Frozen, they reveal some of the extraordinary means that the director and his animators used to achieve those effects of speed. Clampett was also adept at highly exaggerated reactions and hilarious distortions of the animal body. Watching these cartoons with a finger on the pause button can yield hilarity and teach you a lot about normally hidden aspects of the art of animation.

David has written about the artistry in Walt Disney’s films. He points out that a quick movement may be accomplished by adding extra limbs, as when in Melody Time Johnny Appleseed gathers an armload of falling apples and multiple arms and hands convey the speed of his gestures—as do a pair of phantom heads in the uppermost frame of the three David reproduces.

Such multiple images work without our noticing them. It’s not an obvious sort of technique to use. As David wrote, “Through trial and error Disney’s animators learned that rather strange single images will look exactly right on the screen; these men were practical perceptual psychologists.”

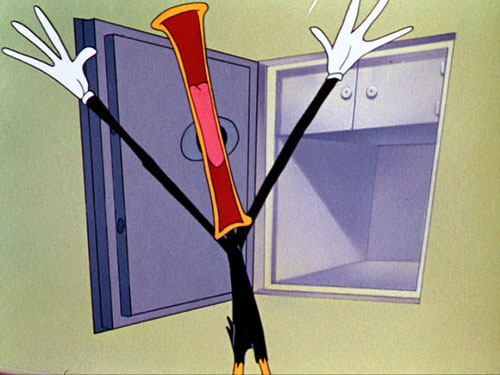

The same was true in the Warners animation department. In The Big Snooze (1946), Clampett’s last cartoon for the studio, he includes a scene of Bugs rapidly tying Elmer to some railroad tracks. In a couple of frames, he sprouts extra arms and hands. In The Great Piggy Bank Robbery (1946), phantom images of Daffy accompany his firing a machine gun.

But Clampett’s single images were often far stranger than the ones in the Melody Time example. In this one from Draftee Daffy, for example, the extra figures of Daffy as he frantically builds a wall between himself and his nemesis (the little man from the draft board) are purple.

I suppose that’s because multiple black figures of Daffy would blend together, but it’s still a bit weird. As an animator, how do you decide on a color?

Maybe it’s because purple is a subdued color that won’t call attention to the extra ducks and yet will contrast well with the black. It’s also the same color as the floor, so that might create an extra reason why we won’t notice them as standing out from the overall composition as it flashes past. If you know those purple ducks are there, you can just barely see them during normal projection. If you don’t know that, then you’re likely to miss them.

(I used that example of Daffy building the wall in my sole academic publication on animation, “Implications of the Cel Animation Technique,” in Teresa de Lauretis and Stephen Heath, eds., The Cinematic Apparatus [St. Martin’s Press, 1980]. There it had to be in black and white, unfortunately.)

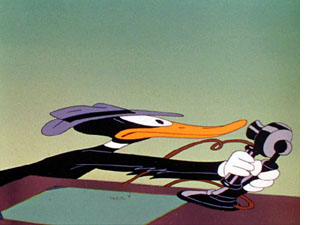

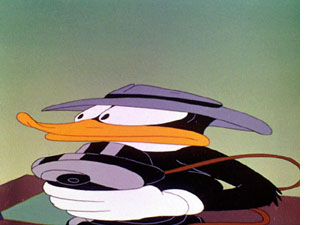

Clampett often draws upon a standard animation device, “stretch,” to convey a sense of speed–although his characters may cross a room in as little as two or three frames. The first image of the telephone scene from The Great Piggy Bank Robbery is a fairly straightforward example of stretch, yet in the same scene, Daffy rapidly turning around uses the opposite technique, “squash.”

A similar technique which Clampett uses occasionally for a character about to launch into a rapid movement is a sort of squash with a perspective effect stretching the character toward the viewer, as in The Big Snooze when Bugs instructs Elmer to “Run this way.” (Bugs isn’t the only one who gets into drag in these cartoons.)

I’ve picked some of my favorite Clampett films, but many frames worth pausing on are to be found in others. With the Looney Tunes boxed sets still coming out, in five volumes to date, one can hunt out the Clampett films–though annoyingly, the indexes list neither the date nor the supervising animator, and there seems to be little logic involved in which films go on which discs. (There are also occasional jumps where something has presumably been censored.) It’s best to get thoroughly familiar with these films by simply viewing them. Then, pick up that remote and begin your search. You’ll discover that Clampett was one of the most imaginative of those “practical perceptual psychologists.”

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery.