Archive for February 2008

Do sell us shorts

Kristin here—

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a single theater playing all five nominees for the best-picture Oscar. It’s happening now at the six-screen Sundance Cinemas here in Madison, plus they’ve got The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (nominated for director, cinematography, adapted screenplay, and editing) and Persepolis (animated-feature nominee). The latter is very impressive, and I think it would win in an ordinary year, but probably not when it’s up against Ratatouille.

[February 9. That outcome seems even more likely now. Last night Ratatouille won nine Annie Awards, prizes given out by the professional animation community. In the 35 years of those awards’ existence, only once has the top animated feature prize not gone to the film that went on to win the best animated film Oscar. Pixar’s accompanying short, Your Friend the Rat, won best short subject. It’s not eligible for an Oscar, since it was a supplement on the Ratatouille DVD and not shown theatrically.]

Films like these get widely seen, obviously. An awful lot of films, though, get nominated for Oscars that far fewer people will see. How many people fill out their office Oscar pool ballots knowing anything about the short animated and live-action films? Some you can track down online or on TV (HBO, Sundance, the IFC, and so on), but viewing them all would be difficult.

For three years now, however, Magnolia Pictures has been packaging the films in those two categories into a single program that goes out to theaters and then onto DVD. Magnolia is a small independent distributor, best known perhaps for its documentaries, including Enron: Smartest Guys in the Room and Capturing the Friedmans and for its imports like Ong Bak and The World’s Fastest Indian.

This year’s program, “The 2007 Academy Award Nominated Shorts,” is listed on the company’s website as playing in 80 theaters, though perhaps that number will rise. Many of the runs (including the one at our Sundance Cinemas) start on February 15, and others are scheduled from then on into April.

Thanks to Sarah Simonds, manager at Sundance, I was able to get an early look at the ten films on the program.

As one might predict, the range of quality is greater in the live-action films than in the animated ones. I’m not sure why that would be predictable, but I have my suspicions. There’s not much of a theatrical market for live-action shorts, which mainly get seen at festivals and on TV. They tend to be portfolio films, made by people trying to attract attention and move up to features. Hence they more often come from beginners. Animators who don’t want to work their way up through big studios—and who stand little chance of ever directing a major animated feature—or who simply value their independence may stick with shorts.

Another factor working in favor of animation is that it’s a medium that demands the detailed planning of literally every frame. No improvisation, no casual shooting in real locales, no direct sound. All in all, I think that if I were an Academy member, I’d have more trouble making a decision in the animated-shorts category.

Real, Live People

In the live-action category there’s no doubt that I would vote for The Tonto Woman, a UK short directed by Daniel Barber from an Elmore Leonard short story. Remarkably, Barber had mainly directed TV commercials before embarking on this, his first 35mm short, as a way of breaking into the film industry. He produced and funded it himself, with a ten-day shoot in Spain using locations and standing sets that had figured in such films as A Fistful of Dollars and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

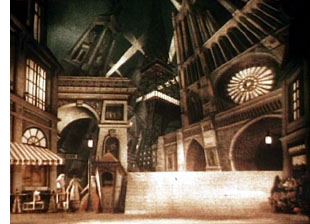

The result might be described as The Piano meets There Will Be Blood. A cattle rustler (well played by Anthony Quinn’s son Francesco) encounters a rich man’s wife (Charlotte Asprey) who is living in enforced seclusion after having been kidnapped and held for eleven years by Mojave Indians (image above). The film has landscapes with the epic quality of both There Will Be Blood and No Country for Old Men, and its drama has the depth of a feature film without feeling rushed in its 35 minutes.

Leonard’s website has a press release giving more details, as well as a profile of Berber. The latter suggests that the director has been contacted by people within the film industry. All I can say is, fund this man immediately. I definitely want to see what he could do at feature length.

David has written quite a bit about the lively contemporary Danish cinema, including two entries on this blog, here and here. The country continues to be on a filmic roll in terms of Oscar nominations, with the short At Night being the one I’d vote if I were an Academy member and weren’t already voting for The Tonto Woman. It’s directed by Christian E. Christiansen and produced by Zentropa with support from the Danish Film Institute.

The subject matter sounds like the sort of thing that would ordinarily make me run the other way: three very young women with cancer bonding in the hospital ward they share. But the film avoids the touchy-feely clichés that so easily could sink such a project (except for a conventional Polaroid-photo montage of their little New Year’s party). It’s not just a sick-women’s-solidarity picture. One does come to care about these three and to understand how their illnesses make them better able to communicate with each other than with their families. It manages to pack a considerable emotional impact into forty minutes. Again, here is someone who could probably direct a fine feature film—and, given the current strength of the country’s industry, may well get the chance.

Tanghi Argentini is a charming comedy from Flemish director Guido Thys, dealing with an office worker who asks a colleague to teach him how to tango to impress a woman he has met on the internet. It combines a clever concept with a surprise twist at the end that works so well in both the short-story and short-film format. It’s entertaining but not so unusual or substantial that I would think of it as Oscar-worthy.

The two other films, France’s Le Mozart des Pickpockets (director/writer/actor Philippe Pollet-Villard) and Italy’s The Substitute (director Andrea Jublin), though both amusing, seemed surprisingly lightweight and conventional to have received nominations.

Puppets and Pictures

Trying to decide which of these animated shorts I would vote for is more difficult. Each is well-executed, entertaining, and imaginative. I tried thinking which I would want to watch again, which I would recommend to friends.

By those standards, there are again two stand-outs for me. I’d ultimately opt for Même les pigeons vont au paradis (Even Pigeons Go to Heaven), a French puppet film by Samuel Tourneux. It’s about a priest who attempts to sell a heaven-simulating machine to a miserly peasant about to be visited by the Grim Reaper. It’s fast-paced, very funny, and beautifully detailed in its depictions of the characters and settings. It’s not claymation, but it has some of the polish and wit of Aardman shorts.

My close second choice would be a very different sort of film, My Love, from Russia, directed by Alexander Petrov. It’s a pretty, lyrical tale of a fifteen-year-old boy’s idealistic yearnings after a pretty servant girl and a more glamorous and mysterious woman who lives next door. The animation is impressionistic and shimmering, with constantly added brushstrokes transforming the compositions. Its visual style is derived from nineteenth-century Russian realist painting, especially that of Ilya Repin.

My close second choice would be a very different sort of film, My Love, from Russia, directed by Alexander Petrov. It’s a pretty, lyrical tale of a fifteen-year-old boy’s idealistic yearnings after a pretty servant girl and a more glamorous and mysterious woman who lives next door. The animation is impressionistic and shimmering, with constantly added brushstrokes transforming the compositions. Its visual style is derived from nineteenth-century Russian realist painting, especially that of Ilya Repin.

Suzie Templeton animating the Duck for Peter & the Wolf*

I suspect the Oscar winner might well be Peter & the Wolf, a British-Polish co-production that illustrates the classic Sergei Prokofiev tone poem. It was directed by Suzie Templeton and made at the Se-ma-for Studios in Łódź. There’s no doubt that it’s an impressive item, with elaborate miniature studio sets that could pass for real landscapes, precise and amusing puppets, and a mind-boggling frame-by-frame manipulation of furry puppets that leaves nary a ripple in their hair. (The photo above hints at how the latter feat was accomplished.) Still, the appeal of the original music is its evocation of events in our mind’s eye, and for me the literal playing out of those events at times carried a faint air of tedium. It’s the sort of prestige project that one can imagine a lot of Academy members loving.

The same cannot be said for the edgier I Met The Walrus, from Canada. It’s derived from an existing soundtrack, a tape-recording made by a 14-year-old Jerry Levitan when he snuck into John Lennon’s hotel room and interviewed him. Now, many years later, director Josh Raskin has created an animated image track to accompany it. It’s a clever idea, but to me the illustrations of Lennon’s words soon became a bit too literal, and I found myself thinking that the animation was Terry Gilliam (in his Monty Python days, that is) meets Yellow Submarine meets Max Ernst collage-novel.

The same cannot be said for the edgier I Met The Walrus, from Canada. It’s derived from an existing soundtrack, a tape-recording made by a 14-year-old Jerry Levitan when he snuck into John Lennon’s hotel room and interviewed him. Now, many years later, director Josh Raskin has created an animated image track to accompany it. It’s a clever idea, but to me the illustrations of Lennon’s words soon became a bit too literal, and I found myself thinking that the animation was Terry Gilliam (in his Monty Python days, that is) meets Yellow Submarine meets Max Ernst collage-novel.

I’m very much of two minds about Madame Tutli Putli, the seemingly inevitable entry from the National Film Board of Canada (directed by Chris Lavis and Maciek Szczerborski). A puppet film four years in production, it is an extraordinary technical accomplishment. It deals with a mousey woman who takes a train journey that confronts her with bizarre and ultimately threatening events. The grim tone and grubby puppets and objects reminded me of Jan Svankmajer’s work.

The most disturbing thing about the images, however, is not the subject matter but the creepily realistic eyes. To me it was obvious that real eyes had been superimposed onto the puppets’ faces. Investigating how this had been done, I found this brief making-of demonstration on YouTube, which indeed revealed the main character to be a puppet with blank areas where the eyes would be. Looking further, I learned that the special effects were done by painter/animator Jason Walker, who devised a complicated process to coordinate the photographed eyes with the animation. Some demonstrations of that process are available here, and there is an interview with him here.

There’s no doubt that the technique is unnerving, and yet at the same time it’s distracting (if one notices it). Is it “fair”? Of course people have been combining live action and animation in various ways since the 1910s. Yet superimposing photographed elements in such a way as to make them appear to be part of the animation almost seems like cheating. Here one would be tempted to marvel at how skillfully the animators had simulated human eyes—a notoriously difficult subject to capture realistically. I suppose for many viewers the eyes and the rest of the image would blend seamlessly and not prove distracting. For me, it didn’t quite work.

Overall, the program is undoubtedly worth seeing on the big screen.

As to the previous two programs of Oscar nominees, see here for the list of 2005 shorts and here for the DVD; see here for the 2006 list and here for the DVD.

*The production image from Peter & the Wolf derives from a making-of short on the British release of the German-made DVD (from Arthaus Musik), which now seems to be out of print.

What happens between shots happens between your ears

DB here:

In Number, Please? (1920) Harold Lloyd plays a lovesick boy who’s been jilted by his girl. Moping at an amusement park, he sees her arrive with a new beau.

He shifts to another spot to watch them. When she notices him, she scorns him, and he reacts.

She and the escort stroll past, then she turns and cuddles up to him, making sure Harold notices.

Her flirting precipitates the rest of the action in this very funny short.

In this scene from Number, Please? Harold and the couple aren’t shown in the same frame. The action is built entirely out of singles of Harold and two-shots of the couple, with an especially emphasized close-up of the girl’s snooty reaction. The sequence is rapidly paced and carefully matched in angle; note the shift in eyelines as the girl and her beau walk a little way and then she looks back at Harold.

This approach to building a scene was consolidated in American studio cinema in the late 1910s, as we noted recently, and it soon spread around the world. One of the places it caught on most fervently was Soviet Russia.

Kuleshov glories in the gaps

The great director and theorist Lev Kuleshov always claimed that he and his associates learned the power of editing from American cinema. Russian films were slowly paced, consisting of long tableaus occasionally broken by an inserted closer view of an actor. (For examples, see my Bauer blog entry from the summer.) Kuleshov noted that the Hollywood films brought into Russia grabbed audiences’ interest more intently, and Kuleshov attributed this effect to the fact that the Americans exploited editing more fully, creating the scene out of many shots.

Kuleshov’s example was the formulaic scene of a man sitting at his desk and deciding to commit suicide. The Russians, Kuleshov claimed, would handle this all in one distant framing, with the result that the key actions were just part of the overall view. By contrast, Americans would shoot the scene in a series of close-ups: the man’s face, his hand taking a pistol out of a desk drawer, his finger tightening on the trigger, and so on. This gave the scene a powerful concreteness, and was cheaper to film besides (no need to have a full set).

But most American filmmakers didn’t create the scene wholly out of close-ups. Typically there would be an establishing shot before the action was broken down into detail shots. The process has come to be called analytical editing. (We discuss it in Chapter 6 of Film Art.) As the label implies, the cutting analyzes an orienting view into its important details.

Less commonly, as in our Number, Please? example, American directors could create a scene entirely out of separate areas of space, without ever showing a master framing. This technique, usually called constructive editing, remains common today as well, especially in action scenes.

While praising analytical editing, Kuleshov was particularly taken with constructive editing, because that shows that cinema can call on the spectator’s tacit understanding to assemble the separate shots. Kuleshov realized that we will build a sense of the scene’s space and action out of separate shots without need for the comprehensive view supplied by an establishing shot.

What the Americans developed, the Soviets thought seriously about. Around 1921, Kuleshov and his students mounted some experiments, several of which he discusses in his books and essays. He probably didn’t need to experiment; the American films were full of examples. Indeed, the Number Please? passage is more intricate than any experiment Kuleshov seems to have mounted. But he had a bit of the engineer about him, and he sought to break the technique into its simplest components.

For one thing, constructive editing offered production efficiencies. You could film two actors separately, at different times, and then cut them together. Further, Kuleshov saw that editing could abolish real-world constraints. It created events that existed only on the screen, with an assist from the viewer’s mind.

This is perhaps best seen in his experiment involving an “artificial person.” Evidently it wasn’t a case of constructive editing, because it seems to have begun with an establishing shot. The first shot shows a girl sitting at her vanity table putting on makeup and slippers. A series of close-ups of lips, hands, legs, and the like were derived from different women, and they were edited together to create the impression of a single woman. (Something of this effect survives in the idea of a body double in contemporary films and TV commercials.) But the point is that the woman on screen, made out of different parts, doesn’t exist in the real world.

The same possibility could apply to geography, if we delete the establishing shot. As Kuleshov describes his experiment, we initially get a shot of a woman walking along a Moscow street. She stops and waves, looking offscreen. Cut to a man on a street that is in actuality two miles away. He smiles at her and they meet in yet a third location, shaking hands. Then together they look offscreen; cut to the Capitol in Washington DC. Kuleshov saw the potential for imaginary geography as both a useful production procedure and a demonstration that editing could create a purely cinematic space, one not beholden to reality.

Kuleshov’s most famous experiment, the one he identified with the “Kuleshov effect” proper, involves a stock shot of the actor Ivan Mosjoukin, taken from an existing film. In his writing he’s rather vague and laconic about the results.

I alternated the same shot of Mosjoukin with various other shots (a plate of soup, a girl, a child’s coffin), and these shots acquired a different meaning. The discovery stunned me—so convinced was I of the enormous power of montage. (1)

Kuleshov’s pupil the great director V. I. Pudovkin offers a different description of the shots: a plate of soup, a dead woman in a coffin, a little girl playing with a teddy bear. He also goes farther in reporting how the audience responded. People read emotions into the neutral expression on Mosjoukin’s face.

The audience raved about the actor’s refined acting. They pointed out his weighted pensiveness over the forgotten soup. They were touched by the profound sorrow in his eyes as he looked upon the dead woman, and admired the light, happy smile with which he feasted his eyes upon the girl at play. But we knew that in all three cases the face was exactly the same. (2)

Now it isn’t only geography or a human body that has been created by editing; it’s an emotion.

These experiments have been poorly documented, and only a couple have survived. One consists of fragments of the imaginary geography exercise. Here is Alexandra Khokhlova waving, but we don’t have the answering shot of the male actor responding. The two meet at the foot of a statue.

After the two shake hands, they look up and out of the frame, but unfortunately we lack the shot of the Capitol.

Kristin and other scholars have written more about these surviving fragments, and their essays are published along with Kuleshov’s proposal for funding the experiments and his wife Khokhlova’s memoir of filming them. (3)

It’s worth taking these prototypes of constructive editing apart a little bit. Clearly, there are several cues that prompt us to see the shots as continuous.

One cue is a common background, or at least a consistent one. Kuleshov thought that sometimes a neutral black background worked best, especially for close shots, as you can see with the handshake shot. Another cue is roughly consistent lighting from shot to shot. Yet another is the presumption of temporal continuity; no moments seem to be omitted in the cut from shot A to shot B. It never occurs to us to consider that Kuleshov’s man is looking at something hours or days before the soup is laid on the table in the second shot.

One of the most important cues goes unmentioned by Kuleshov: the very act of looking. Like most commentators, he seems to take it for granted. Yet it’s crucial in prompting us to imagine an overall space in which the actions take place. Knowing the real world as we do, we can infer that if you’re close enough to watch someone, both people are probably in a shared space, such as the arcade strip in the amusement park in Number, Please?

Another cue is facial expression. In his soup/girl/coffin sequence, Kuleshov supposedly picked a shot of Mosjoukin that doesn’t have a clearly identifiable expression. If Mosjoukin was smiling in his interpolated shot, he would presumably seem not grieving but wicked. Normally, though, performers seen in the single shot are expected to express the appropriate emotion more fully, in order to specify what we take the characters’ mental states to be. Our sequence from Number, Please? makes sure we understand the drama by giving the actors unambiguous expressions.

Finally, in the Kuleshov prototypes each shot should be simple. Its action can be stated in a brief sentence. A woman waves. A man responds. A man looks. A plate of soup sits on a table. Even in Number, Please? we can summarize each shot: Harold looks off. His former girlfriend disdains him. That’s to say that the shots are composed to present only one, quickly grasped point of interest.

Filmmakers don’t need to tease apart all these cues; they use them intuitively. Soon after Number, Please?, Hollywood filmmakers were creating amazing passages of eyeline-match editing—the most virtuoso being probably the racetrack sequence in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1926). Within a few years of Kuleshov’s experiments, Soviet filmmakers were creating their own masterworks, like Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Kuleshov’s By the Law (1926). Benefiting from a very compressed learning curve, filmmakers took constructive editing to new heights.

Constructive editing, dissolved relationships

Sometimes constructive editing is used to save a scene when production goes astray. When Doug Liman reshot the climax of The Bourne Identity, Julia Stiles couldn’t be on set, so singles of her taken from the first version were wedged in among the retakes, to create the impression that she was watching Jason confront his controller. More positively, a carefully calibrated constructive editing is central to a sequence I analyzed a while back in In the City of Sylvia. For over 100 shots, the spatial relations are built up without an overall establishing shot. (4)

Constructive editing can be used systematically throughout a film. A good example is Alan J. Pakula’s thriller Presumed Innocent (1990). Spoilers coming up!

Harrison Ford plays Rusty Sabitch, a prosecutor in the District Attorney’s office who becomes infatuated with a new woman on the staff. He has a brief affair with her, but after she’s broken it off she’s found brutally murdered. He has to investigate the crime without involving himself, but eventually he becomes the prime suspect.

At the start of the film before Rusty learns of the murder, Rusty and his wife Barbara are shown at breakfast, and establishing shots bring them together.

At the office Rusty learns of Carolyn’s death, and after he comes home, the conversation between Rusty and Barbara is treated without an establishing shot. Barbara knows about the past affair, and Rusty is wracked by guilt and shame. The cutting seems to reflect the fact that Carolyn’s death has revived the pain in their marriage.

In a series of flashbacks, Rusty relives his affair with Carolyn. Pakula treats their early encounters by means of constructive editing. The common-background cue is especially helpful in this scene in a kindergarten.

Only after Carolyn and Rusty cooperate and win a child-abuse case does the cutting’s rationale become clear. Pakula has saved the traditional two-shot framing for their moment of passion, as they make furious love in the office.

But soon their affair wanes and Rusty is reduced to watching Carolyn from across the street in point-of-view shots.

After the flashbacks end, Rusty is investigated and eventually charged with Carolyn’s murder. In these scenes Pakula often situates Rusty and Barbara in the same frame, as if the threat to him has healed the breach between them.

Yet in the film’s climax—and here is the big spoiler—they are pulled apart again. The last scene is a sustained monologue by Barbara. As Rusty listens, across twenty-six shots the two are never shown in an establishing shot.

Contrary to the standard Hollywood ending, in which the loving couple embrace in reunion, here they are left divided.

Pakula’s use of constructive editing has effectively traced two arcs: the growth and dissolution of Rusty’s affair, and the reuniting and dissolution of his marriage. In such ways, what might seem a purely local effect, confined to a handful of shots, can create stylistic patterning across a film. The judicious use of constructive editing matches the dramatic development.

Godard of the gaps

Robert Bresson has made more varied and complex uses of constructive editing across a film, as I tried to show in Narration in the Fiction Film and in an Artforum essay. (5) A more radical approach, somewhat in the purely Kuleshovian spirit, can be seen in Godard’s films since the late 1970s. In presenting a scene, Godard often omits an establishing shot, so constructive editing takes over. But he makes the technique quite abrasive and ambivalent.

In watching films like Number, Please? and Presumed Innocent, we fill in the gaps between shots with ease. Godard, however, makes his images and sounds more fragmentary by equivocating about the Kuleshovian cues. The background elements and lighting don’t match entirely; time seems to be skipped over; glances and facial expressions are ambivalent. Adding to these factors, lines of dialogue slip in from offscreen. Godard does present a dramatic scene taking place, but he also creates a sense that images and sounds have been pried loose from their place in an ongoing action, floating somewhat free and functioning as objects of contemplation for their own sake. The cues that Lloyd insists on and that Kuleshov plays with are ones that Godard suppresses or makes ambiguous.

I’ve mentioned this tendency in a recent entry, but to elaborate a little, consider the science lecture in Hail Mary (Je vous salue Marie, 1985). A professor who has emigrated from an Eastern bloc country is explaining his theory that life on earth began and evolved because it was directed by extraterrestrials. No establishing shot of the classroom shows us where he, Eva, and two male students are located, so we have to construct a rough sense of their positions on the basis of a few cues. As Eva, perched on a windowsill, toys with a Rubik’s cube, we hear the professor’s lecture begin to speculate on whether life could have evolved spontaneously. His remarks about sunlight coincide with a burst of sun on her face.

After the Biblical title, “In those days,” we get a series of shots that allow us to apply our mental schema of a classroom lecture: attentive students looking off, a professor at the blackboard.

Lacking an establishing shot, we can’t specify how many people are in the class, nor indeed where Eva and her classmate are sitting—since the professor looks off in several directions during his talk.

At the end of his talk he remarks, still scanning the room, that we can presume that life exists in space. “We come from there.” At that point Godard cuts to the head of another student, seen from behind. The sproingy haircut is a little explosion of yellow, and it’s accompanied by a burst of choral music. And as the shot goes on, we start to notice that the professor is pacing in the background, out of focus.

The student, whom we’ll learn is named Pascal, asks a question (at least the slight head movement suggests that it comes from him), and the professor replies. Pascal scratches his head as the professor continues, still out of focus. If I had to choose one shot that condenses Godard’s strategy of suppression in this sequence, this shot would be my candidate.

At the end of the shot, the professor asks Eva to stand behind Pascal. Cut 180 degrees and somewhat farther back to Pascal, now seen from the front. The professor’s hand brings the Rubik’s cube into the shot and Eva comes up behind Pascal as the professor passes.

Later she and the prof will become lovers, but Godard lets them meet first as simply two torsos intersecting behind Pascal. The purpose is a demonstration that a “blind” agent can be steered toward a goal through simple yes/no commands. This models the professor’s theory that an alien intelligence could have guided evolution.

Pascal will twist the facets of the cube under Eva’s hints. Godard makes this a tactile, even erotic exchange, with the close-up of her by his ear and Eva saying, “Yes,” more urgently as Pascal’s hands arrive at a solution, in the close-up surmounting this blog entry.

The next two shots of the sequence center on the prof, who has exited frame right from the “three-shot.” Now he’s at the window, recalling the initial shot of Eva; but unlike her he’s little more than a silhouette. As crashing organ music is heard, he seems to be watching the experiment from afar. The second shot, an axial cut-in, coincides with the offscreen voice of a male student: “Were you exiled for these ideas?”

“These ideas, and others,” the prof replies. He says he’ll see the class on Monday, evoking the idea that he’s dismissing the offscreen students, and he turns his head slightly, though we can’t be sure they’re on his right. This shot will be held for some time as students quiz him more about his theory, and Eva asks him if he’d like to come over for a drink some evening. But we don’t see her say it. Godard cuts to a shot of Eva at the window, bathed in sunlight, opening and shutting her eyes as she slightly lifts and lowers her head.

As we see her, we hear the rustling of people leaving (so the class was evidently larger than three). And we hear him reply to her invitation, “That’s another story [scénario].” Are Eva and the prof looking at each other? We’re inclined to say yes, but her closed eyes and tilting head suggests someone lost in contemplation rather than engaged in conversation. Here the classic facial-expression cue is made indeterminate. We have no way of knowing if the prof’s line comes from offscreen, or is displaced from another point in time; maybe he has left the room. Such displaced diegetic sound occurs elsewhere in the film.

We don’t have to decide; our indecision is the point. By pruning away the most reliable cues, Godard wins both ways. We’re kept somewhat oriented to an intelligible action: a prof sets forth his far-fetched theory of human origins and a woman in his class invites him for coffee. This side of the balance allows us to feel that a story, however sketchy, is moving forward.

But the moment-by-moment texture of the scene allows the individual shots, gestures, and sounds to drift somewhat free. Each image takes on a more intrinsic weight, and the juxtaposition of picture and sound acquires a resonance that we usually call poetic. A shot of Eva in the sun playing with the Rubik’s cube, unanchored in time (during class? before class started?), invites us to apply metaphors, especially once we learn her name. Pascal’s thorny hair suggests not only extraterrestrials but the explosion of a nova. The silhouetted prof, detached from the mechanism he has set in motion, hints at an unknown deity watching the game play out according to his rules. Why do Godard films spawn long essays built out of erudite associations? Because the narrative progression relaxes and we can weave our own connotations out of what we see and hear.

If you don’t want to go down the expanding-association route, there’s another one open. When individual moments no longer accumulate ordinary dramatic pressure, we can savor the fugitive pleasures of the separate shots (light on face, lips by ear) and the patterns they form: flipover cuts, yellow hair and yellow facets, bookended shots of Eva at the window.

Those patterns, it should be clear, depend on our sensing a bump at every shot change, looking for a way to skip across the gap that Godard creates. The same belief that meaning and effect are born of gaps impelled Kuleshov too, and perhaps even Lloyd. If we pay attention to those gaps we can feel minds—both the filmmaker’s and ours—at work in them.

(1) Lev Kuleshov, “’50’: In Maloi Gznezdinokovsky Lane,” Kuleshov on Film, trans. and ed, Ronald Levaco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 200.

(2) V. I. Pudovkin, “The Naturschchik instead of the Actor,” Selected Essays, ed. and trans. Richard Taylor (Oxford: Seagull, 2006), 160.

(3) See Kristin Thompson, Yuri Tsivian, and Ekaterina Khokhlova, “The Rediscovery of a Kuleshov Experiment: A Dossier,” Film History 8, 3 (1996), 357-367.

(4) The sequence does begin with a long shot of the café, but it is so distant, crowded, and brief that it can’t really be said to establish the spatial relationships among the several characters we see.

(5) “Sounds of Silence,” Artforum International (April 2000): 123.

All singing! All dancing! All teaching!

Kristin here—

David and I are currently revising our second textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for a third edition due out next year. As part of the research, I’ve been watching two recent DVDs on the early history of sound and color. Both offer valuable resources for those teaching introductory film-history classes, as well as more specialized ones.

Twenty-five years ago, when I last taught a survey history class, the resources for teaching about the innovation of sound were discouragingly limited. The early Vitaphone shorts were as yet unrestored, with most of their accompanying discs damaged or lost. The most famous early sound films were mainly available in mediocre 16mm prints. Showing an “early” sound film often meant a René Clair classic from the early 1930s—a time when the transition to sound was well along, if not over. Le Million or Á nous la liberté demonstrated the artistry that an imaginative director could bring to the early sound cinema, but it wouldn’t give much idea of the struggle inventors and filmmakers went through to create the complex technology.

The same was true for pre-1935 color. There was no way to adequately survey the range of processes and experiments, from early hand painting and stenciling to two-strip Technicolor. The poor 16mm prints of early films often gave no real indication of what they had looked and sounded like when they were made.

Since then archivists have been intensively discovering and preserving films, and in some cases these have been released on DVD. Often these discs are simply collections of films, but documentaries incorporating short films and clips are becoming more common, especially since they make attractive television programs.

Discovering Cinema (Flicker Alley)/Les Premiere pas du cinéma (Lobster & histoire)

A two-DVD survey from the very active Lobster archive in Paris devotes a disc each to sound (2003) and color (2004). Lobster is a private archive started in 1985 by two film enthusiasts, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange. (The website offers a choice of French or English text.) It began as an effort to discover lost films. Building on its success, Lobster has grown into a major resources for restoring films—both their own discoveries and commissions from other archives and from film companies.

David and I bought this set when it came out. The French boxed set offers a choice of French- or English-language versions. (It’s not region-coded, but it is PAL, which means it won’t play on NTSC players, the standard in the U.S. and some other countries.) The French version isn’t on the Amazon.fr site, but fnac is offering it.

In September, 2007, the American version was released by Flicker Alley. This is another private archive, founded in 2002, also by an enthusiast, Jeffery Masino. The company hasn’t put out many titles yet, but the DVDs available so far are impressive. Flicker Alley collaborates with Turner on restorations, and presumably its catalogue will grow.

Each Lobster documentary is about 52 minutes long, and the supplements include a number of complete films.

The disc devoted to color is subtitled “Un rêve en couleur” and in English the slightly more poetic “Movies Dream in Color.” It’s organized by the three types of cinematic color: Colors and Tints (that is, black and white film painted or dyed), Additive Synthesis (using filters on the projector lens to add color to black-white film), and Subtractive Synthesis (recording separate colors on separate strips of film and combining them in printing).

The disc devoted to color is subtitled “Un rêve en couleur” and in English the slightly more poetic “Movies Dream in Color.” It’s organized by the three types of cinematic color: Colors and Tints (that is, black and white film painted or dyed), Additive Synthesis (using filters on the projector lens to add color to black-white film), and Subtractive Synthesis (recording separate colors on separate strips of film and combining them in printing).

There’s a quick run-through on color in pre-cinema devices: slides, peep shows, and topical toys. The next section gives a splendid demonstration of how stencils were used to hand-color films (such as the unidentified example above), as well as some briefer coverage of tinting and toning.

Moving to additive color systems, the film deals with Friese-Green’s early experiments, Charles Urban’s Kinemacolor, with its brief commercial success, Gaumont’s technically sophisticated Chronochrome, and various lenticular systems. Given that these attempts require special projection, the recreated examples given here are one of the few ways that we can see such films today. All of them proved dead ends, however, so they are of more interest for their technical ingenuity than for their ultimate impact.

The final part of the film turns to Technicolor, founded in 1915. The firm quickly turned away from its early additive experiments and settled on a subtractive system using two strips of film and later, in the 1930s, three strips—resulting in the vibrant hues that many people still think of as the acme of filmic color. “Movies Dream in Color” gives a brief but useful run-down of Technicolor’s progress, through its early two-strip successes like The Black Pirate through the exclusive contract with Disney in the 1932-36 period, and its triumph thereafter as the main color system of Hollywood. There is also some coverage of the two brands that combined all colors on a single negative, Kodachrome and Agfacolor, but the coverage essentially ends in 1939, before either had become widespread.

Incidentally, an in-depth study of Technicolor has recently been published: Scott Higgins’ Harnessing the Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s.

The filmmakers weave together interviews with a number of prominent archivists, including Paolo Cherchi Usai (co-founder of “Le Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival and now director of Australia’s national archive) and Gian Luca Farinelli (director of the Cineteca di Bologna).

“Learning to Talk” (in the French set “Á la recherche du son”) uses the same group of experts and a somewhat similar three-part organization: “artistic sound” (that is, live sound during the projection of silent films), sound on disc, and sound on film.

The segment on live sound is excellent. It again starts with pre-cinema music and effects for magic-lantern shows and progresses to Reynaud’s hand-drawn Pantomimes lumineuses, with their specially written music. One highlight is documentary footage of a man demonstrating the use of an elaborate sound-effects box, with its brushes, cans of pebbles, and other crank-operated devices that simulated such actions as trains moving and crockery being smashed.

The sections devoted to sound-on-disc and sound-on-film are less well set forth, since the filmmakers try to cover many pioneers in France, the U.S., Germany, and Denmark. Again, several of the devices covered were novelties that led nowhere or that failed for lack of amplification, the use of non-standard film widths, and other reasons.

Once the story reaches the lengthy invention process of the two main American systems, Warner Bros.’ Vitaphone (using discs) and Fox’s Movietone (sound-on-film), it proceeds more clearly. “Learning to Talk” includes some of the Case and Sponable demo films, a Movietone News interview with Mussolini, and a clip from Don Juan. Presumably because of rights problems, no footage from The Jazz Singer is shown.

The bottom line is that the color disc strikes me as the more useful for teachers. The sound one gives good coverage, but again many of the systems discussed are not historically significant to anyone but specialists. For a history of that deals largely with the American innovation of sound, one can now turn to a superb recent DVD.

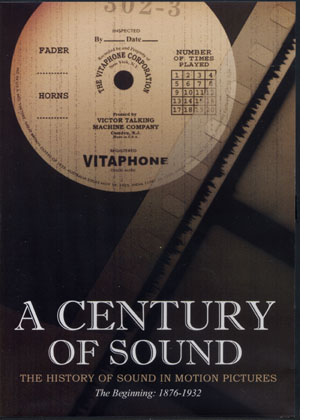

A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures: The Beginning: 1876-1932 (UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Rick Chace Foundation).

This disc originated in a lecture on early sound by Robert Gitt, who has long been the preservation officer for UCLA’s film archive. Gitt has supervised on the restoration of many important films. In 1991 his team launched the Vitaphone Project. Vitaphone, Warner Bros.’s commercially successful sound system of the 1926-31 period, used phonograph records rather than optical tracks on the film strip. Over the decades many of those discs were damaged or separated from the original reels, and the Vitaphone shorts sat in their cans, reduced to silence.

Gitt and company set about finding as many discs for the surviving Vitaphone films as they could. Over the years they were amazingly successful in tracking them down and rejoining sound and image in a sound-on-film format that can be shown on modern projectors. You can trace the progress of the project since its beginning through its online newsletter, which currently runs from fall, 1991 to winter, 2007/08.

Colleagues urged Gitt to turn his lecture on sound, copiously illustrated with clips, into a DVD. He took the opportunity to expand the talk and to incorporate more and lengthier clips. Most documentaries on film history include only brief clips from any scene. Gitt has wisely opted to include whole scenes, and he has had access to high-quality archival prints of the key early sound films. He also offers early tests made by the companies responsible for innovating sound, as well as documentary shorts they used in selling their processes to industry executives. Rather than writing a script for someone else to read, Gitt appears as presenter and narrator. He humorously admits to the dullness of some of the technical shorts and acknowledges the occasionally silly or racist content of some of the films. At the same time, though, he makes clear what is significant about the examples he presents, and they all become more intriguing than they would if seen individually, out of context.

Colleagues urged Gitt to turn his lecture on sound, copiously illustrated with clips, into a DVD. He took the opportunity to expand the talk and to incorporate more and lengthier clips. Most documentaries on film history include only brief clips from any scene. Gitt has wisely opted to include whole scenes, and he has had access to high-quality archival prints of the key early sound films. He also offers early tests made by the companies responsible for innovating sound, as well as documentary shorts they used in selling their processes to industry executives. Rather than writing a script for someone else to read, Gitt appears as presenter and narrator. He humorously admits to the dullness of some of the technical shorts and acknowledges the occasionally silly or racist content of some of the films. At the same time, though, he makes clear what is significant about the examples he presents, and they all become more intriguing than they would if seen individually, out of context.

The result offers an extraordinary array of clips that teachers could draw upon even if they don’t have time to show the entire lengthy documentary. For Vitaphone there are some of the early shorts, the entire duel scene from Don Juan, extended excerpts from The Better ‘Ole, Old San Francisco, Lights of New York, and others. For Fox Movietone there are scenes from 7th Heaven and Sunrise, as well as George Bernard Shaw’s charming appearance in an issue of Movietone News.

Despite some lively moments, many of the early sound films are slow and clunky, due to the limitations of the available equipment. Gitt balances them by ending with some familiar examples of the imaginative early use of the new technique: the “Paris, Please Stay the Same” number from Lubitsch’s The Love Parade, a generous excerpt from Mamoulian’s Applause, and a portion of I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (which, be warned, gives away the ending). Teachers whose schedules don’t permit them to devote precious screening time to an early sound feature can give their students a reasonably good sense of the transitional period with such clips.

We’ve all heard the stories about how certain actors’ careers were destroyed by sound, but for the teacher there’s again the problem of how to demonstrate this to classes. Gitt has filled this need as well. Among the bonuses (which are few because so much is included in the film), there is one on the fates of actors. For each Gitt supplies both a clip of the actor in a silent film and in a sound one. The actors whose careers took a nose dive in sound films are represented by Rod La Roque, Norma Talmadge, John Gilbert, and Charles Farrell. Those who successfully made the transition are Ronald Colman, Joan Crawford, William Powell, and Laurel and Hardy. Gitt makes plausible cases why the public responded to each actor as it did.

As the disc’s title implies, it is intended to be part of a series of three documentaries that will cover the entire century. If Gitt continues to get access to the sort of material he presents here, the result should be an impressive overview of the subject and a boon to educators. If in the 1970s and 1980s we had dreamt up our ideal documentary subject for teaching early sound, it would have looked a lot like A Century of Sound—except we couldn’t have imagined all the material that existed in the vaults, waiting to be found and restored.

A Century of Sound is not available commercially. Educators and researchers can request a free copy (with a $10 shipping charge) by downloading a pdf form here.

The Jazz Singer (Warner Bros.)

Released this past October, this three-disc deluxe set marks the first time that The Jazz Singer has been on DVD. (Legally, that is; there was apparently a Chinese bootleg.) It also includes numerous supplements, some of which might be useful for teaching the introduction of sound.

The first disc contains the restored print of The Jazz Singer, a complete version of Al Jolson’s Vitaphone short, A Plantation Act, and some other shorts. One of these is the classic Tex Avery cartoon, I Love to Singa, inspired by The Jazz Singer and starring “Owl Jolson.”

An 85-minute documentary, The Dawn of Sound: How Movies Learned to Talk is the main item on the second disc. It was made by Turner Entertainment and bears a copyright date of 2007. Like so many TV shows, it doesn’t trust enough in the inherent interest of its topic. Rather than explaining the sound systems clearly by type, the writers have opted to try and stress the four Warner brothers as interesting personalities (not very successfully) and the intense competition among the sound systems in the late 1920s. The opening third cuts together too many brief, unidentified film clips and talking-heads comments, which doesn’t make for a coherent introduction to the topic. The production of the Vitaphone shorts is not well explained, though the film does point out that the shorts were more influential than Don Juan in making the new process appeal to audiences. There are excerpts from the main early Warners sound films, as well as a section on actors who succeeded or failed in talkies.

Another item on this second disc is the entire surviving footage—two scenes—from Gold Diggers of Broadway, a two-strip Technicolor musical from 1929. It’s rather an arbitrary inclusion, but as it’s not likely to come out on DVD in any other context, we should be grateful to have it. The scenes are pretty dreadful, apart from the spectacularly cubistic melange of Parisian landmarks in the set.

Another item on this second disc is the entire surviving footage—two scenes—from Gold Diggers of Broadway, a two-strip Technicolor musical from 1929. It’s rather an arbitrary inclusion, but as it’s not likely to come out on DVD in any other context, we should be grateful to have it. The scenes are pretty dreadful, apart from the spectacularly cubistic melange of Parisian landmarks in the set.

The rest of the disc consists mainly of some older documentaries on early sound made by Warner Bros. One, The Voice from the Screen (1926) was intended as a demonstration of Vitaphone for technicians. The presenter is not, to say the least, charismatic, and it’s obvious why Discovering Cinema and A Century of Sound use only excerpts. Nice to have it complete, but students wouldn’t sit still for the whole thing. The Voice that Thrilled the World was directed by Jean Negulescu in 1943, on the occasion of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences adding a best-sound Oscar—the first of which happened to go to Warners’ Yankee Doodle Dandy. This short seems to be the source for the staged footage of early sound breakthroughs that show up, unidentified, in The Dawn of Sound and the other documentaries. Not surprisingly, The Voice that Thrilled the World primarily hypes the Vitaphone process.

“Okay for Sound” (1946) celebrated the twentieth anniversary of Don Juan’s premiere, and it recycles a lot of material from the 1943 short. Like The Voice that Thrilled the World, it was a theatrical short, intended as much to promote current Warners’ films as to celebrate the studio’s past triumphs. The film handily includes an extended clip of Jolson singing the saccharine “Sonny Boy” number in The Singing Fool (1928).

(A companion book with a slightly different title, “Okay for Sound!” was published in 1946. It’s a picture history of sound. The photos are not well produced, and many are just publicity stills from films. It does contain quite a few photos of sound equipment. It turns up with surprising frequency in used-book stores. The phrase, by the way, is what recordists would call out to indicate to directors when the sound was operating and the action could start–their equivalent of the camera operators’ “Speed!”)

When the Talkies Were Young (1955) is an odd, low-budget documentary that consists of fairly extended clips from some early Warners’ talkies: Sinners’ Holiday (1930), 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932), Night Nurse (1931), Five Star Final (1931), and Svengali (1931). These aren’t bad, though unfortunately the narrator occasionally interjects comments during the action.

The third disc contains over three and a half hours of restored Vitaphone shorts, a treasure trove for teachers who want to show some examples of these. The first one, Behind the Lines (1926), is the example we use in our box on “Early Sound Technology and the Classical Style” in Chapter 9 of Film History: An Introduction (see Figures 9.4 and 9.5, p. 197 in the second edition).

If I had to make a choice of just one of these three DVD releases in looking for clips for a unit on early sound, I would favor A Century of Sound as having the best organized presentation and the most useful set of excerpts. The “Learning to Talk” disc could be useful as a briefer, self-contained teaching tool. The Jazz Singer package is a bit of a hodgepodge, but educators who want to deal with early sound in depth could pluck out some very useful additional material from it.

A May 12, 1925 Case test with Gus Visser and his duck singing a duet of “Ma, He’s Making Eyes at Me.” (Added to the National Film Registry in 2002 and included in both Learning to Talk and A Century of Sound.)