Fair is still fair, and more so

Wednesday | April 23, 2008 open printable version

open printable version

Film Art: frames from Election illustrating the concept of motifs

Kristin here—

Back in 1977, when David and I began writing Film Art: An Introduction, we knew from the start that we would use frame enlargements as illustrations. At the time, that wasn’t common practice for film books, even textbooks. One reason was that it was difficult to obtain such images, but perhaps even more daunting was the notion that using frame enlargements would violate copyright. But Film Art came out of classes we had been teaching, and there we used slides of frames and 16mm clips during lectures to illustrate cinema techniques, style, and form. We didn’t see any way we could write it without photographing and reproducing actual frames.

From the start, we assumed that using frames in an educational context would be fair use. A few frames from a film would be comparable to a few words from a poem or a novel, we figured. We didn’t request permission to reproduce most of the frames printed in the book. The exceptions were films by experimental filmmakers, whom we asked more out of courtesy than because we figured we legally needed to.

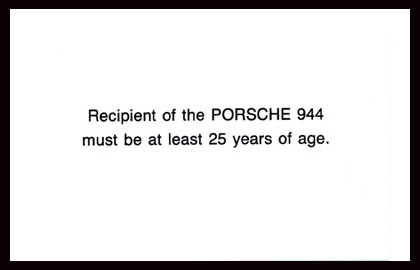

One pleasant incidental result of such requests was that we now have autographs from Norman McLaren, Michael Snow, Ernie Gehr, and Bruce Connor. These unfortunately are on dull request forms. Connor livened his up a bit by adding, “I own the splices on my films. The images from individual frames are not copyrighted by myself.” He also enclosed the accompanying card as a little surrealist gesture.

One pleasant incidental result of such requests was that we now have autographs from Norman McLaren, Michael Snow, Ernie Gehr, and Bruce Connor. These unfortunately are on dull request forms. Connor livened his up a bit by adding, “I own the splices on my films. The images from individual frames are not copyrighted by myself.” He also enclosed the accompanying card as a little surrealist gesture.

We never got in trouble with the copyright holders for reproducing the hundreds of frames in Film Art. Most of our other books have also involved frames, from Méliès shorts to The Lord of the Rings.

The 1993 Report on Fair Use and Film Stills

Initially some of our editors were a bit reluctant to include those frames unless we obtained permissions from the copyright holders, but we managed to talk them into it. Then, in the early 1990s, I was asked to chair a special committee of the Society for Cinema Studies (now the Society for Cinema and Media Studies) to investigate the question of fair use of film frames and photographs. The result was the “Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Society for Cinema Studies, ‘Fair Usage Publication of Film Stills,’” written by me with help from my colleagues John Belton, Dana Polan, and Bruce F. Kawin. Experts, including the Register of Copyrights, Ralph Oman, and Prof. Peter Jaszi, an expert on copyright law, contributed their thoughts on the matter. The report first appeared in the Winter 1993 issue of Cinema Journal and is available online.

The fair-use law itself is simple. Here are the factors to be considered in determining whether the reproduction of a work violates its copyright:

1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

That last one seems to me particularly important for scholars, since it would be very difficult, if not impossible to prove that anything we publish diminishes the market value of the original. Quite the contrary, we help in our own small way to publicize that original.

I argued in the report that fair use did apply to film frames used in an educational context. The case for reproducing publicity and other behind-the-scenes photographs was considerably less clear, since unlike film frames, photographs can be individually copyrighted.

The report has had salubrious effects on film publications. Slowly more journal and academic-press editors accepted the idea that fair use does mean that authors don’t need to seek permissions. Given that most big studios either ignore such requests or demand hundreds or even thousands of dollars for their consent, the new policies of many journals and presses was a great boon to cinema studies. Gradually more and more scholarly and educational publications used frames instead of publicity stills, which made their descriptions and analysis much more effective. By now the use of film frames has become common practice.

Some encouraging cases

Occasionally, however, someone who is nervous about using frames writes to me to ask if anything has happened since 1993 that would change the situation. Has anyone been sued by a film studio for using film frames? Has a precedent been set?

In the report, I predicted that no studio would ever sue over the academic use of film frames. That was partly because the studios have bigger fish to fry, particularly the huge question of how to prevent film piracy. In contrast to bootleg DVDs selling for a couple of dollars in the streets of Shanghai or Moscow, we film scholars do not figure in the consciousness of the studio legal departments.

There have been some events that I think make it worth revisiting the issue of fair use in a more informal way here.

First, the very fact that the use of frame enlargements has become so common and that fewer academics seek permissions from copyright holders itself sets a precedent. As I said, it’s common practice now. I assume there probably are still editors who would rather be safe than sorry and demand that the author obtain permissions for illustrations. I assume there are probably some authors who abide by that decision or who are themselves worried about copyright and so do seek and even pay for unnecessary permissions. As always in discussing this issue, I urge editors and authors not to seek permissions, since it sets a different and dangerous precedent, implying that fair use might not apply in such publications.

Second, there have been some interesting court cases which don’t involve film frames but which do suggest that fair use applies to the sorts of images that film scholars might wish to employ.

In August of 2006, a decision came down in the case “Christopher R. Harris v. San Jose Mercury News.” (See here for an article on the case from Communications Lawyer.) Like many other newspapers, the Mercury News had used a photograph from a book in a review of that book. The newspaper cropped the photo, including eliminating the copyright notice. Harris, the photographer, sued for infringement.

The closing argument was presented by Gary Bostwick, of the major law firm Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton, which works in, among other areas, entertainment law and intellectual property rights law. An abridgement of Bostwick’s argument for the reproduction of the photo as fair use is included in the article linked above. The article concludes: “The jury deliberated for only thirty-seven minutes before concluding that copying photographs from books for use in reviews was fair use.”

If a newspaper review can reproduce photographs, surely a scholarly book could claim an even greater right to do so.

Recently I sat down with my friend and colleague, James Peterson, of Godfrey & Kahn, S.C., who practices intellectual property rights law here in Madison. James got his Ph.D. in film studies at the University of Wisconsin. His dissertation (the committee for which David co-chaired along with J. J. Murphy) was subsequently published as Dreams of Chaos, Visions of Order: Understanding the American Avant-Garde Cinema (Wayne State University Press, 1994). The book contains frame enlargements, obviously vital in any attempt to analyze experimental films. James’s expertise in film studies and his subsequent law degree make him particularly attuned to the needs of scholars in the field and the rights involved in using images in academic publications.

During our conversation, I mentioned that many books using frame enlargements had been published since the SCS report was published. James responded:

On the frame enlargements issue, to me, really, although there’s no case law verifying the old SCS analysis from twenty years ago, I think it’s right. I don’t have any reason to doubt it. Now, I have a personal commitment to it myself, because I relied on it when I did my book. Nothing in my experience as a lawyer has led me to think otherwise … I think the position on frame enlargements is much more secure than on production stills. Marginally more at least.

I mentioned that David and I had also used production stills in our books without seeking permission. James responded:

I would think that those are fair, too. To me the biggest case is the Bill Graham Archives case (the district court case in the letter) and that was affirmed right down the line by the second circuit court of appeals. So to me that’s a huge fair-use case for scholars.

The case James refers to is one he cited to me in a letter summing up his opinions on the fair-use status of various kinds of illustrations that I wanted to use in The Frodo Franchise. The second circuit court of appeals he refers to is in New York, and it often handles major cases involving copyright law.

The case in question was “Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Limited, Dorling Kindersley Publishing, and RR Donnelley & Sons Company.” At issue were some illustrations in a book, Grateful Dead: The Illustrated Trip. This was a coffee-table cultural history of the band, done with the members’ cooperation. The book reproduced without obtaining permission seven images on which the Bill Graham Archives claimed copyright. There had in fact been some negotiations between the publishers and the archive, but as a fee could not be agreed on, the illustrations were reproduced without permission. The copyrighted images had been “originally depicted on Grateful Dead event posters and tickets.”

The court decided in favor of the publishers, declaring the reproduction of the seven images constituted fair use and thus upholding the lower court’s decision. In summing up, the court declared (using the four factors determining fair use listed above):

On balance, we conclude, as the district court did, that the fair use factors weigh in favor of DK’s use. For the first factor, we conclude that DK’s use of concert posters and tickets as historical artifacts of Grateful Dead performances is transformatively different from the original expressive purpose of BGA’s copyrighted images. While the second factor favors BGA because of the creative nature of the images, its weight is limited because DK did not exploit the expressive value of the images. Although BGA’s images are copied in their entirety, the third factor does not weigh against fair use because the reduced size of the images is consistent with the author’s transformative purpose. Finally, we conclude that DK’s use does not harm the market for BGA’s sale of its copyrighted artwork, and we do not find market harm based on BGA’s hypothetical loss of license revenue from DK’s transformative market.

James expressed his opinion about the decision: “At least on the use of illustrative material, I think that case is very powerful.”

Powerful indeed, because it suggests that film scholars would be justified under fair use even if they reproduced whole production photos, posters, and other visual material directly related to the discussion in the text of their book or article, all without seeking permission.

I mentioned the widespread use of frame enlargements and photographs on the internet, particularly on fan websites. James gave his opinion on the use of photos on websites and then on our blog particularly:

The stock-photo houses are best positioned to complain about that activity, because they’re in the business of selling into that market. So if you want to illustrate something on your website, you shouldn’t just snatch it and stick it on the website.

You guys are, to my way of thinking–what you are doing is almost infringement-proof, because you’re unimpeachably scholarly and you’re writing about the things that you’re copying. It would be different if you were just using it to illustrate your website. I think a lot of the fan sites might fall into that category. They’re not connecting scholarship about the thing. They’re using the things they’re copying to attract attention to their own work. That, I think, is a different enterprise.

All of this is good news for cinema studies. So yes, things have happened since 1993 that would change the situation for film scholars, and it’s all for the better. Fair use is obviously alive and well, and those of us who need to reproduce the images we discuss can do so. Let’s all go analyze a film!

Note: Important policy statements on fair use in related areas have been released in the past few years. For the use of copyrighted material in documentary films, see the Center for Social Media’s “Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use” (2005) and its follow-up on the statement’s impact.

In 2007, the Society for Cinema and Media Studies released a statement targeted at classroom teaching: “The Society for Cinema and Media Studies’ Statement of Best Practices for Fair Use in Teaching for Film and Media Educators,” in Cinema Journal Volume 47, no. 2 (2008) or online.