Archive for June 2008

Years of being obscure

DB here:

The Cannes screening of Ashes of Time Redux reminds us that Wong Kar-wai has been an incessant reviser of his work. Versions proliferate in different markets—one for Hong Kong, one for Taiwan, one for the international market—and he has sometimes promised online versions, or bonus DVD features. Buenos Aires Zero Degree (1999) by Kwan Pung-leung, provides tantalizing bits of scenes between Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Shirley Kwan. Yet it makes us wonder about the film we might have had if Wong had not decided to cut the whole plot strand out (after keeping Shirley in Argentina for several weeks).

We can add to the list Days of Being Wild (1990), Wong’s breakthrough movie. It’s been circulated for years in an international version, which is currently available on DVD. But some people people have recalled seeing a fugitive, somewhat hallucinatory cut of the film. Some time ago I examined that alternative, and I figured it’s worth showing what I saw. This rareversion prefigures some aspects of Wong’s later style, particularly as seen in In the Mood for Love (2000). I don’t have solutions to all the puzzles it poses, but I’ve gathered some information. If you know something about this “obscure” version, feel free to write to me and I’ll append your comments to this entry.

I need hardly add that there are spoilers galore here. In the images, differences in tonality and aspect ratio spring from my two sources, DVD and 35mm film (which itself fluctuates a little in aspect ratio from shot to shot).

Last things first

Days of Being Wild begins in 1960 Hong Kong. It follows the wanderings of Yuddy (Leslie Cheung), a preening young man who casually seduces women, notably the brassy Lulu (Carina Lau) and the subdued, naïve Lai-chen (Maggie Cheung). Living with his aunt, Yuddy wonders why his mother abandoned him. He finds her living in the Philippines but doesn’t confront her.

At the climax in Manila, Yuddy meets a sailor (Andy Lau) and picks a fight with local thugs. The two men flee by hopping aboard a train. By chance, the sailor was formerly a Hong Kong cop, who was attracted to Lai-chen. On the train, Yuddy is shot by a vengeful thug. The film concludes with a series of shots of Lulu, Lai-chen, and—the big mystery—a slick young man in a seedy apartment who files his nails, combs his hair, equips himself with handkerchief and cigarettes, and sets out for a night on the town. He doesn’t speak, and he has never appeared in the film before. It’s one of the boldest narrative maneuvers in contemporary cinema, and it has occasioned a lot of comment.

The differences in the final sequences begin on the train. In the international version, a shot of the landscape seen from between the cars is followed by a high-angle medium shot of the cop.

This constitutes a mini-flashback, since Yuddy has already died from the gunshot. The cop’s voice-over initiates the exchange: “The last time I saw him, I asked him a question.” (As usual in Wong’s work, we have no way of knowing whom is being addressed; this could be an inner monologue, a report to an unseen character, or simply a self-conscious address to the audience.) For a little more than two minutes, the camera shows only the cop. He asks if Yuddy remembers what he was doing at a certain time. Yuddy understands immediately that the cop has met Lai-chen, and he replies from offscreen, asking about the cop’s relation to her and asking him to tell her that he, Yuddy, has no memory of her. The cop worries that Lai-chen may not even recognize him.

The exchange ends with a wordless shot of Yuddy sitting against the seat, eyes barely open, as an orchestral version of “Perfidia” rises up. The scene ends with an extreme long-shot of the train. The tune was heard earlier when the cop walked away from a nighttime encounter with Lai-chen, so this refrain reminds us of the cop’s yearning for her.

The alternate version doesn’t alter the overall situation much, but it presents different emphases. After the shot between the train cars, we have an off-center long shot of the cop; it’s then that we get the voice-over: “The last time I saw him, I asked him a question.” Cut to a medium close-up of Yuddy, which replaces the shot of the cop. Now for about two minutes he speaks and the cop’s reactions are kept offscreen.

As far as I can tell at this point, the dialogue is identical. In effect, we have a virtual shot/ reverse-shot exchange between the two films! And instead of holding on the framing of Yuddy, or cutting to the cop’s reaction, Wong simply gives us a shot of the two men in facing seats. This is followed by a very different shot of the train, winding through the sort of greenish-blue foliage seen in a famous earlier shot, and there is no music.

The international version puts the emphasis on the cop, who is both challenging Yuddy and obliquely reflecting on his own situation.; hence perhaps the “Perfidia” theme, which is associated with him. The alternate version keeps us focused on Yuddy throughout, our final stare at him, as it were, before a two-shot reasserts an equivalent weight between the two men, and perhaps their memories as well.

The very end

The variations continue in the final shots. Both versions begin with the shot of Lulu striding to the camera in a telephoto framing, above. Now she’s in the Philippines.

In the international version, this shot is followed by Lulu swanning into a bedroom, hanging up her dress, and saying to the landlady, “There’s someone I want to ask you about.”

In the other version, we see her passing through a somewhat sleazy hotel lobby and asking for a spare room. As a result, it’s somewhat less clear that she’s pursuing Yuddy.

The scene shifts to the stadium where Lai-chen works as a ticket seller. (Stephen Teo’s stimulating book on Wong specifies that it’s the South China Athletic Association.) Customers are swarming in for a football match. The obscure version gives us two quick tracking shots of the crowd, with the second ending on a profile shot of Lai-chen in her booth.

The standard version offers only one of the tracking shots and ends with a static framing of the profile composition. But this version adds a shot, beginning the scene with a head-on composition of her at her window.

At this point the alternate version omits two shots that have attracted a lot of critical commentary. Before the shot of Lai-chen shutting up shop, we see a high-angle view of tramway tracks and a shot of a clock outside the stadium.

The clock shot recalls Lai-chen’s meeting with Yuddy, while the tramcar lines recalls her rainy-night encounter with the cop. Instead of these empty shots, the alternate version cuts from Lai-chen in her booth to a shot of a soccer match, evidently seen through a slot in her cabin.

The rest of what follows corresponds in both versions. Lai-chen is seen reading a newspaper before closing the booth.

Both versions likewise wind down with a shot of the phone booth, the one that Lai-chen and the cop had lingered beside, followed by a closer view of the interior. The phone is ringing.

The first shot of the pair recalls, in its high-angle composition, the rainy night that the two met. (Wong’s characters are haunted by memory, but he forces us to use ours too.)

The cop had asked Lai-chen to call him, and the previous scene showed her closing her window, so we might infer that now she’s trying to get in touch with him—not knowing, as we do, that he’s quit the force, become a sailor, and watched her boyfriend die. But we can’t be sure that she’s the one making the call.

The very last shot, showing Tony grooming, is also the same in both versions. (One stage of it is at the very top of this entry.) It is a real crux. Why is Wong showing us this down-at-heel gambler for two and a half minutes? He has no evident connection to any of the characters we’ve followed, and we will never see him again.

Most critics have also accepted Wong’s explanation that he had planned a sequel, one showing how Yuddy’s influence over others lingered long after his death. Patrick Tam told Stephen Teo that the shot was his idea, a setup or trailer for the next film, turning everything we had seen up till now into a lengthy prologue. (1) But Days of Being Wild was a fiasco at the box office, taking in HK$9.7 million, or about $1.25 million US (in a year in which Stephen Chow’s All for the Winner earned over four times that). So the sequel was never made.

Yet these intriguing circumstances don’t really justify the epilogue’s purposes and effects. A causal explanation doesn’t necessarily yield a functional explanation. What role does this disruptive shot play in the film’s overall dynamic? If Wong had made the sequel, it might have been seen as a brilliant stroke; without the followup film, how can we justify its presence?

It’s reasonable to argue, as Teo does, that this vision of Tony’s primping generalizes Yuddy’s case, suggesting that his rootless narcissism is a condition of many young men of the day. You might also suggest that he provides a sort of male equivalent of the playgirl Lulu; just as the cop played by Andy Lau is a good, though unachieved, match for Lai-chen, Tony would pair up better with Lulu than Yuddy’s pal (Jacky Cheung), who pines for her.

Actually, the alternate version sheds a little light on the problem. It doesn’t provide a definitive answer to what Tony is doing there, but it does offer some tantalizing possibilities. In the alternate version, Tony is not only the last character we see, but the first one. And he’s embedded in a sequence that looks ahead to the style for which Wong has been both admired and castigated.

Languor and ellipsis

After the credits, the international version opens with Yuddy striding forcefully into the soccer stadium and mesmerically flirting with Lai-chen. But the print I examined of the obscure version interrupts the credits and shows us none other than the nameless young spark played by Tony Leung Chiu-wai, buffing his nails. (It seems to be an earlier stretch of the final shot, which continues this action.)

Over his image, we hear this in a male voice (no subtitles on the print):

I saw him one more time. He had just returned from the Philippines. He was much thinner than before. I asked him what happened to him. He replied that he just recovered from his sickness. He didn’t want to chat anyway, so I asked him what his sickness was.

Afterwards, we didn’t see each other any more.

This is very mysterious. Whose voice is speaking—Tony’s, Yuddy’s, Andy Lau’s? I can’t identify it. And who is the he referred to? The most plausible candidate is Andy, who may have returned to Hong Kong; and he is looking fairly ill in the film’s final scenes. But it might be the Tony character, as described by one of the other men, or even at a stretch Yuddy himself, who has somehow survived the shooting and returned to Hong Kong.

These ruminations assume that this opening shot frames a flashback by rhyming with the final image of Tony rising from the bed and dressing for his night out. It provides a sheerly formal justification for the final shot, which now completes the action begun at the start. But substantively, we’re still left with a variant of the original question. Instead of asking why end the movie with this remote character, we now ask why he’s used to frame the movie.

The questions have just begun, however. After this eighteen-second shot of the dapper Tony, we get a music montage lasting about eighty-three seconds. It’s quite perplexing. We’re in a warren of corridors, a bit reminiscent of the byways of Chungking Mansions in Chungking Express, and everything is in slow motion. We follow Andy Lau, in a yellow pullover, striding through the darkness and sweating profusely. Then we find him playing cards with some unidentified men. At one point, we see a woman climb the stairs, at other points we glimpse a man with an enormous snake coiled around him. The sequence ends with shots of a hand seizing a cleaver and shots of Andy, back in the corridor, striding away from us. The whole sequence is accompanied by the song “Jungle Drums,” which continues from the shot in Tony’s apartment but is now sung by a female voice (Anita Mui’s).

I was able to take stills of these shots, so I’ll go through them one by one, despite their iffy quality. (The images are very dark, and the print was worn and a little speckled.) After the opening shot of Tony, we get eighteen shots, all in slow-motion, many out of focus, and nearly all using camera movement. Often the cuts are matched in the normal fashion, but sometimes the connection is purely kinetic. As often in Wong’s work, the timing of the cuts synchronizes with beats or melodic lines in the music.

The first shot shows a woman ascending a staircase (pre-echo of the cheongsams in In the Mood for Love), and we pan quickly to Andy looking up after her before setting out down the corridor, where he passes a man with a snake.

Track left with Andy in medium close-up, wiping sweat from his face, then cut to an out-of-focus shot of him still walking.

Andy rounds a corner and proceeds down the hall, extending his hand to the wall. In one of those pseudo-matches, another hand slides open a door, as if completing his gesture. We see a card game inside. The framing suggests Andy’s point of view, but the camera glides back.

In close-up, a hand holds a cigarette. A slight tilt and rack-focus reveals that the card player is Andy.

Suddenly, there’s an out-of-focus shot of the snake sliding along the man’s arm; the shot lasts only 16 frames, or two-thirds of a second. (Here I go again, frame-counting.) This is followed by a blurry shot, only 19 frames, of Andy turning his head. It’s almost as if the snake-shot had attracted Andy’s peripheral vision.

The man with the snake, still out of focus, rises and goes behind a curtain. Cut to a shot of a light bulb shielded by a scrap of paper, with cigarette smoke wafting up.

A classic misterioso shot: A powerfully built man in a suit, seen from the rear, dominates the composition, and the camera tracks back from him. But instead of revealing his identity, the narration cuts back to Andy, who, out of focus, turns back to the game.

A new phase of the sequence starts. The camera pans up a rock wall, showing water trickling down it. Confirming that we’re back in the corridor, we see a hand seizing a chopper from a wall rack. There’s an odd effect of matching movement, with the pan upward picked up by the upward-lifting movement of the cleaver.

From another angle, the hand draws the cleaver across the frame.

Now we get opposing lines of movement—up and to the right in the first chopper shot, horizontally to the left in this shot. The rhythmic bump is accented by the brevity of the shots (30 frames, 21 frames). At the end of this second shot, we can glimpse someone walking away in the dark background.

The cleaver shots are followed by a close-up of Andy walking along the corridor, much like those at the start of the sequence. The final shot shows him walking far away from us. This take seems to be a continuation of the earlier one, when he put out his hand against the left wall. It fades out as the song does.

After the fade-out of Andy walking down the corridor, the credits resume and the scene introducing Yuddy and Lai-chen begins the main plot.

Wong had used a music montage in As Tears Go By (the remarkable “Take My Breath Away” sequence, which I analyzed in Planet Hong Kong). But there it functioned as a lyrical commentary on a sharply delineated, somewhat conventional narrative situation: Wah visits Ngor in Lantau Island and awkwardly communicates his affection for her. This sequence in Days is puzzling because it doesn’t have very clear narrative import. It does set the mood of languor that dominates the film, but it also hints at a situation of criminal danger (gamblers, the hand with the chopper) that is never actualized in the story that follows.

Coming after the fairly opaque opening shot of Tony, this sequence poses other questions. We’ll later learn that Andy is a diligent patrolman; what’s he doing in this den of thieves? Local audiences would recognize the location as the Kowloon Walled City, a sort of island of sheer criminality in the middle of Kowloon. Was Andy an undercover cop before taking up the uniform?

And who is seizing the cleaver? At first I thought it was Andy, but closer inspection shows that’s not likely; there’s nothing in his hands in the final extreme long-shot. Is someone stalking him? We never find out.

Wong is fond of giving us mere impressions of events, sometimes linked to characters’ consciousness, sometimes soaring cadenzas of images blended with music. But unlike the music montage of As Tears Go By and those in later films, this one is almost indecipherable in story terms. Nothing else in Days of Being Wild is as free-form as this stretch of footage. It can stand as an emblem and limit-case of Wong’s interest in using genre conventions poetically, and his reluctance to pay them off in plot terms.

Partial solutions, more mysteries

Back in 2001, Shelly Kraicer, impresario of the Chinese Cinema List, wrote about having seen this version, and several people chimed in with their recollections and opinions. In 2004, I asked several Hong Kong friends about it. Filmmaker, critic, and educator Shu Kei, who has a long memory for Hong Kong film, replied:

I remember the footage you describe. If I’m right, this was the version WKW re-edited after the disastrous midnight premiere of the film, and it was the “official released version” for the regular shows in the following week.

Days was released on 15 December 1990 and played until 27 December, so perhaps this was indeed the version that was seen in its Hong Kong run. In 2001 correspondence on Shelly’s list, Bérénice Reynaud, who saw the “pre-premiere version” of a print straight from the lab, was “positive” that the prologue material was not in that print.

Shu Kei offers some further information about the gambling sequence:

The shots with Andy Lau in a card game and fighting afterwards [sic] were done in a very early stage of the film’s lengthy shoot, in which Lau was playing a gangster-like character in the Kowloon Walled City. (The role, and much of the original concept of Days of Being Wild, were reprised in Jeff Lau’s Days of Tomorrow, 1993.) Andy’s character was later changed to that of a cop.

Two other Hong Kong observers told me that the revised version was designed to make sure that the big stars Tony Leung and Andy Lau had early and prominent entrances, since without the prologue, they play minor roles. Michael Campi reported in the 2001 correspondence: “I was told that in a frantic attempt to retrieve some revenue from the film, it was decided crassly to include Leung Chiu-wai in the opening as well as the closing.”

If this was the strategy, it’s reminiscent of the changes made to the international (originally, Taiwanese) version of Ashes of Time, with the prologue and epilogue showing explosive fighting scenes. Those passages were designed, explains Hong Kong Film Festival programmer Li Cheuk-to, to assure viewers that there would be swordplay in this rather talky movie.

Things are far from settled, though. The prologue is a major crux, but assuming that the last reel I saw was that of the 1990 retooled version, how do the circumstances outlined above explain the disparities in the endings? Why would audience dissatisfaction or producers’ demands force Wong to eliminate the empty shots of the stadium and the clock? Or substitute a different (and more opaque) scene of Lulu in the Philippines? Or change the découpage of the train dialogue between Yuddy and the cop? Or supply a different long shot of the train? Or eliminate the haunting “Perfidia” theme?

Moreover, we still don’t know what the premiere version screened at midnight shows was like. Was it congruent with today’s international version, or was it yet a third variant? In other words, did Wong un-revise the original, or re-revise it? At what point did he or his distributors replace the obscure version with the one in general circulation?

Earlier in June our blog discussed Grover Crisp’s visit to Madison, in which he argued that in an important sense every film exists in alternative versions. We simply have to accept that. It’s especially true of Hong Kong films, which are recut for circulation in many markets. And I like knowing that there’s an especially puzzling variant of Days of Being Wild—one that lets us imagine virtual narrative possibilities and adds to the appeal of this enigmatic movie. Nonetheless, I’d welcome more information about all this, especially from Wong Kar-wai himself.

(1) Stephen Teo, Wong Kar-wai (London: BFI, 2005), 45.

Thanks to Alex Wong for translating the prologue’s voice-over narration for me.

Times go by turns

Kristin here—

Last week during the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference here in Madison, I got to talking with Prof. Birger Langkjær of the University of Copenhagen. He asked me some questions about the concept of “turning points” in film narrative as I had used it in my book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique. Specifically he wondered if turning points invariably involve changes of which the protagonist or protagonists are aware. The protagonist’s goals are usually what shape the plot, so can one have a turning point without him or her knowing about it?

I couldn’t really give a definitive answer on the spot, partly because it’s a complex subject and partly because I finished the book a decade ago (for publication in 1999). It seemed worth going back and trying to categorize the turning points in films I analyzed. Describing those turning points more specifically could be useful in itself, and it might help determine to what extent a protagonist’s knowledge of what causes those turning points typically forms a crucial component of them.

Characteristics of turning points

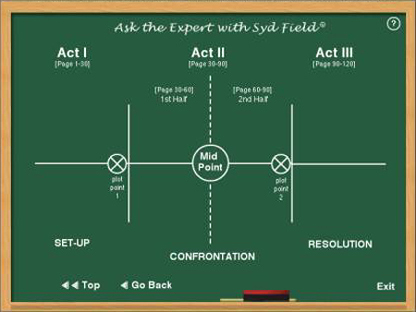

Most screenplay manuals treat turning points as the major events or changes that mark the end of an “act” of a movie. Syd Field, perhaps the most influential of all how-to manual authors, declared that all films, not just classical ones, have three acts. In a two-hour film, the first act will be about 30 minutes long, the second 60 minutes, and the third 30 minutes. The illustration at the top shows a graphic depiction of his model, which includes a midpoint, though Field doesn’t consider that midpoint to be a turning point.

I argued against this model in Storytelling, suggesting that upon analysis, most Hollywood films in fact have four large-scale parts of roughly equal length. The “three-act structure” has become so ingrained in thinking about film narratives that my claim is somewhat controversial. What has been overlooked is that I’m not claiming that all films have four acts. Rather, my claim is that in classical films large-scale parts tend to fall within the same average length range, roughly 25 to 35 minutes. If a film is two and a half hours rather than two hours, it will tend to have five parts, if three hours long, then six, and so on. And it’s not that I think films must have this structure. From observation, I think they usually do. Apparently filmmakers figured out early on, back in the mid-1910s when features were becoming standard, that the action should optimally run for at most about half an hour without some really major change occurring.

Field originally called these changes “plot points,” and he defined them as “an incident, or event, that hooks into the story and spins it around into another direction.” Perhaps because of that shift in direction, these moments have come more commonly to be called “turning points.” But what are they? Field’s definition is pretty vague.

In Storytelling I wrote, “I am assuming that the turning points almost invariably relate to the characters’ goals. A turning point may occur when a protagonist’s goal jells and he or she articulates it .… Or a turning point may come when one goal is achieved and another replaces it.” I also assumed that a major new premise often leads to a goal change (p. 29). “Almost invariably” because I don’t assume that there are hard and fast rules. As with large-scale parts, my claims about other classical narrative guidelines aren’t prescriptive in the way that screenplay manuals usually are.

To reiterate a few other things I said about turning points. They are not always the same as the moments of highest drama. Using Jaws as my example, I suggest that the moments of decision (not to hire Quint to kill the shark and later to hire him after all), rather than the big action scenes of the shark attacks, shape the causal chain (p. 33).

Not all turning points come exactly at the end of a large-scale part of the film (an “act” in most screenplay manuals). A turning point might come shortly before the end of a part, or the turning point may come at the beginning of the new part (pp. 29-30). The final turning point that leads into the climax comes when “all the premises regarding the goals and the lines of action have been introduced” (p. 29).

Most screenplay manuals consider goals to be static. To me, “Shifting or evolving goals are in fact the norm, at least in well-executed classical films” (p. 52). This doesn’t mean that the goal changes at every turning point. Instead, the end of a large-scale part may lead to a continuation of the goal(s) but with a distinct change of tactics (p. 28).

One big advantage of talking about different types of turning points is that it allows the analyst to see how the different large-scale parts function. A well-done classical film doesn’t just have exposition and a climax with a bunch of stuff in the middle. (Field calls that long second act the “Confrontation” in the diagram above.) I believe that once the setup is over, there is a stretch of “complicating action,” which often acts as a sort of second setup, creating a whole new situation that follows from the first turning point. The third part is the “development,” which often consists of a series of delays and obstacles that essentially function to keep the complications from continuing to pile up until the whole plot becomes too convoluted. The development also serves to keep the climax from starting too soon. The third turning point is the last major premise or piece of information that needs to be set in place before the action can start moving toward its resolution in the climax.

David uses this approach to large-scale parts in his online essay, “Anatomy of the Action Picture,” which discusses Mission: Impossible III.

TYPES OF TURNING POINTS

Returning to some of the examples I used in Storytelling, let’s see what sorts of changes their turning points involve. In most of these cases, the protagonist is aware of what is happening, but there are some exceptions or nuances.

1. An accomplishment, later to be reversed

Top Hat: end of setup, Jerry and Dale fall in love, but she soon conceives the mistaken idea that he is married to her best friend. (p. 28)

Tootsie: end of setup, Michael gets a job, but the results will throw his life increasingly into chaos. (p. 60)

Parenthood: end of complicating action, the parents seem to be making progress in solving their problems. (p. 268)

2. Apparent failure, reiteration of goal

The Miracle Worker: end of development, parents remove Helen from cabin, Anne states goal again. (p. 28)

The Silence of the Lambs: turning point comes at beginning of development, Chilton makes Lecter a counter-offer, removing him from the FBI’s charge. The FBI’s tactic has failed, but soon Clarice visits Lecter to pursue her questioning. (p. 123)

Here’s a case where we don’t see Clarice learning about Chilton’s treacherous undermining of the FBI’s efforts. A few scenes later she simply shows up to visit Lecter, and we realize that she has not given up her goal of getting information from him. Clearly a turning point can occur without the main character’s knowledge, but he or she will usually learn about it shortly thereafter.

Groundhog Day: end of development. Failure to save old man. No reiteration of goal, which is implicitly that Phil will continue to improve himself. (p. 147)

2a. Failure, new goal

Amadeus: end of complicating action, Salieri declares that he is now God’s enemy and will ruin Mozart. (p. 195)

Amadeus is an example of what I call a “parallel protagonist” film. Here Salieri is aware of his own decision, but Mozart never learns that his colleague hates him so. Parallel protagonists have separate goals, but they need not be aware of each other’s goals. The same would be true in a film with multiple protagonists, to the extent that they have separate goals.

2b. Failure, lack of goal

Groundhog Day: end of complicating action, suicidal despair. (p. 144)

Amadeus: end of setup, Salieri humiliated by Mozart, conceives strong resentment but no specific goal. (p. 191)

Parenthood: end of development, the parents are all resigned to their failures. (pp. 275-76)

3. Major new premise, reiteration of strategy

Witness: end of complicating action, Carter tells Book to stay hidden. (p. 29)

The Wrong Man: end of complicating action, Manny is freed on bail; he has the chance to try and prove his innocence. (p. 39)

Terminator 2: end of development, Sarah, Terminator, and John steal chip from Cyberdine, continue in their attempt to destroy it. (p. 42)

Amadeus: end of second development, Constanza leaves Mozart, allowing Salieri the access that will permit him to fulfill his goal of killing his rival. (p. 205)

4. Protagonist/Important character makes a decision, then changes or modifies goal

Little Shop of Horrors (1986): end of complicating action, Seymour agrees to kill someone to feed blood to Audrey II. (p. 29)

The Godfather: end of development, Michael says family will go legit, asks Kay to marry him. (p. 30)

Casablanca: end of complicating action, Rick rejects Ilsa’s account of her relationship with Victor. (p. 32)

The Producers: end of setup, Leo decides to join Max in committing fraud. (p. 38)

Tootsie: end of complicating action, Michael decides to start improvising Dorothy’s lines, setting up “her” success. (p. 64)

Back to the Future: end of development. Martie decides to leave a message for Doc warning him about the Libyan attack; the result is to save Doc from being killed. (p. 94)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of setup, Roberta apparently decides to pursue Susan, change her boring life. (p. 166)

Such decisions obviously form the basis for turning points fairly frequently, and by definition the protagonist is aware of what is happening.

5. Major Revelation, new goal or move into climax

Witness: end of setup, Book is told the killer is a cop, changes tactics, flees. (p. 28)

Witness: end of development, Book learns partner has been killed, realizes he must act. (p. 29)

The Bodyguard: end of development, revelation of Nikki as villain, attack on house, death of Nikki. (p. 31)

Terminator 2: end of setup, John discovers the Terminator must obey him, sets goals of protection without killing and of rescuing Sarah from the asylum. (p. 41)

Terminator 2: end of complicating action, Sarah realizes that the war can be prevented, conceives goal of killing Dyson. (p. 42)

Tootsie: end of development, Michael’s agent tells him he must get out of playing Dorothy without being charged with fraud. (p. 69)

The Silence of the Lambs: end of setup, Clarice finds the body in the warehouse and realizes that Lecter is willing to help her. (p. 115)

The Silence of the Lambs: end of development, Clarice and Ardelia realize “He knew her,” the clue that will lead to the solution. (p. 126)

Alien: end of development, revelation that the “company” and Ash are prepared to sacrifice the crew; will lead to decision by survivors to abandon the ship and save themselves. (p. 299)

Such revelations usually involve the protagonist knowing what is happening, but I believe there are exceptional cases where the viewer learns something that the protagonist does not. This kind of revelation often involves either villains turning out to be allies or apparent allies turning out to be villains.

Take the case of Demolition Man. At 54 minutes into the film, about nine minutes before the end of the complicating action, the audience learns that the apparently benevolent Dr. Cocteau (Nigel Hawthorne), who has developed the new pacifist society of Los Angeles, is a ruthless villain. This moment isn’t the turning point that ends the complicating action; I take that to be the escape of the “Scraps,” the rebels who oppose Cocteau, from their underground prison. Most of those nine minutes consist of the hero, John (Sylvester Stallone) meeting Cocteau and going out to dinner with him. John shows signs of strongly disliking the new society, and he refuses to kill the rebels when they escape. Still, there is no sign that he considers Cocteau a villain. Rather, John thinks of himself as a misfit and expresses a desire to leave the new Los Angeles. The turning point that ends the complication depends on his assumption that Cocteau on his side, even if John considers the leader’s bland society to be unattractive.

The development portion is full of typical delays: the scene of John visiting Lenina Huxley’s (Sandra Bullock) apartment, where she invites him to have virtual sex, and the following scene of John exploring the odd, modernistic apartment assigned to him. At 74 minutes in, or about six minutes before the end of the development, John begins to learn of Cocteau’s true nature. He confronts Cocteau in the latter’s office and nearly shoots him. The scene where John tells the members of the police department who remain loyal to him that they will invade the underground prison to capture Cocteau’s violent agent, Simon Phoenix (Wesley Snipes) marks the end of the development, with a new, specific goal determining the action of the climax.

Here is a case where for a significant portion of the narrative the protagonist remains ignorant of something that the audience has been shown. Even here, however, John displays a dislike of Cocteau and what he has done to Los Angeles society. Classical films seem disinclined to show their heroes as thoroughly deluded. John’s underlying decency and common sense make him ready to distrust a leader whom everyone else, including Lenina, admire.

6. Enough information accumulates to cause the formulation of goals

Back to the Future: end of complicating action, goals of synchronizing with lightning storm, getting Marty’s father and mother together at dance. (p. 90)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of complicating action. Information about gangsters and growing attraction to Dez lead to convergence of Roberta’s goals. (p. 170)

Parenthood: end of setup, in this case with multiple goals formed for four separate plotlines.

7. A disaster, accidental or deliberate, changes the characters’ situations/goals

The Wrong Man: end of setup, Manny is mistakenly arrested. (p. 39)

Jurassic Park: end of complicating action, Nedry shuts down the electricity grid of the park, letting the dinosaurs loose. (p. 32)

Jaws: end of complicating action; the attack involving his son makes Brody force the mayor to accept his original, thwarted tactic of hiring Quint. (p. 34)

Alien: end of setup, facehugger attaches itself to Kane. The goal conceived shortly thereafter is to investigate it and save him. (p. 292)

Alien: end of complicating action, alien bursts from Kane’s stomach; goal becomes to save the crew and ship. (p. 295)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of development, Roberta’s arrest leads to a low point, and she opts to turn to Dez for help. (p. 172)

Amadeus: end of first development, death of Leopold, which Salieri later exploits in his plot against Mozart. (p. 201)

The Hunt for Red October: end of complicating action, Ramius realizes he has a saboteur aboard and needs Ryan’s help; Ryan starts planning actively to help him. (p. 233)

8. Protagonist’s tactics are blocked or he/she is forced to use the wrong tactics

Jaws: end of setup, Brody’s desire to hire Quint rejected. (p. 23)

Back to the Future: end of setup, Doc sets time machine’s date; after new large-scale section begins, attack by Libyans accidentally sends Marty back to 1955. (p. 85)

Groundhog Day: end of setup, Phil trapped in repeating time, goal of becoming a network weather forecaster destroyed. He soon opts for irresponsible self-indulgence. (p. 139)

9. Characters working at cross-purposes resolve their differences

Jaws: end of development, the three main characters bond, allowing them to cooperate to kill the shark. (p. 35)

The Hunt for Red October: end of development, Ramius and Ryan make contact, with Captain Mancuso’s help, they start working together. (p. 237)

10. A supernatural premise determines a character’s behavior

Liar, Liar: end of setup, Max wishes that his father would have a day where he is unable to tell a lie. Also end of complicating action, where Max fails to cancel the wish. (p. 38)

11. The protagonist/major character succeeds in one goal, allowing him/her to pursue another

Liar, Liar: end of development, Fletcher wins his court case, freeing him to try and regain his wife and son. (p. 39)

The Hunt for Red October: end of setup, Ramius learns that the silent feature of his new submarine works; he apparently intends some sort of attack on the US but is in fact plotting an elaborate ruse to defect. (p. 225)

These examples suggest that protagonists usually do know about the major events that form turning points, or they learn about them shortly after they occur. The main exception would seem to be when there are two major parallel characters, one of whom is to some extent villainous, as in the case of Amadeus, where one of the characters is duped. This reminds me of The Producers, where Max and Leo leave the theater early, convinced that they have succeeded in their goal of creating a box-office disaster. Lingering in the theater, the narration allows us to see the transition from audience disgust to fascination. Only after the audience comes into the bar where the two partners are celebrating do they realize what has happened (“I never in a million years thought I’d ever love a show called Springtime for Hitler!”) To understand the irony and/or humor in such situations, the film spectator must at least briefly know more than the main characters do.

The examples also confirm that character goals seldom endure unchanged across the length of a film. Revelations, decisions, disasters, supernatural events, and presumably others kinds of causes frequently cause major shifts in characters’ goals or at least in the tactics they employ in pursuing them. Even in what seems like a fairly straightforward thriller like Alien, the crew’s assumptions that they must loyally protect their spaceship are completely reversed at the end of the development, and the narrative turns into an attack on corporate greed and ruthlessness. Whatever one thinks of classical Hollywood films, they are usually more complex than the three-act model allows for.

Note: My title comes from Robert Southwell’s poem of the same name.

[July 11: Jim Emerson has made some insightful comments on this entry on his Scanners blog.]

American (Movie) Madness

Grover Crisp and Lea Jacobs outside the University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque.

DB here, again:

He holds sway over thousands of movies and the transfer of hundreds of DVDs. At home he has a high-definition set, but he gets local channels on a rabbit-ears antenna. If that isn’t a working definition of a Film Person, I don’t know what is.

Over the years our UW Film Studies area has hosted many visiting Film Persons, including archivists Chris Horak, Mike Pogorzelski, Joe Lindner, Schawn Belston, and Paolo Cherchi Usai. (1) Being a department centrally interested in film history, we’re eager to screen recent restorations and learn the ins and outs of film archivery.

This year our Cinematheque screened several Sony/ Columbia restorations, running the gamut from Anatomy of a Murder to The Burglar. We wound up our series, and our season, with a stunning print of Frank Capra’s American Madness (1932). To conclude things with a bang, Lea Jacobs, Karin Kolb, and Jeff Smith brought Grover Crisp, Sony’s Senior Vice President of Asset Management, Film Restoration, and Digital Mastering.

Kristin and I had met Grover at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, and after hearing him introduce some restorations, we knew he had to come to Madison. It was a Bologna screening of American Madness that convinced me that we had to show this sparkling print on our campus. Fortunately for us, Grover squeezed a Madison visit into his schedule and suffered the caprices of American Airlines’ delays. We had about two days of his company.

It was a great learning experience. On Thursday 8 May he addressed our colloquium, where he showed two shorts: a 1933 Screen Snapshots installment explaining the process of motion picture production, from script to final product, and a trim 75-second short by his colleague Michael Friend tracing the evolution of filmmaking technology. On Friday Grover introduced American Madness and took questions.

Just a note about terminology: Archives engage in both film preservation and film restoration. Preservation means, as you’d think, saving films for the future. This involves maintaining the materials (prints, negatives, camera material, sound tracks) in surroundings that minimize harm and deterioration. Restoration demands more resources. It involves trying to create an authoritative version of the film as it existed in some earlier point in history. But that’s a complicated matter, as we’ll see.

Archives and assets

Grover brings a Film Person’s sensitivity to the mission of film preservation. What does that mean? For one thing, he takes the long perspective. Film archivists think about how to store and maintain films for decades, even hundreds of years. In an industry geared to short-term cycles, booms and busts and jagged demand curves, a commercial archivist like Grover, or Schawn of Fox, has to reconcile traditional museum standards with market demands, strategic release considerations, and current studio policies. In short, he has to think both about saving the film for a century and about hitting a DVD street date.

Grover explained his obligations at Sony Pictures Entertainment. He manages all film and television materials. That means preserving everything for any future use and restoring some items for video and theatrical screening. It also means that he keeps abreast of current TV and film productions. This gives him a chance to “embed archival needs” into production and postproduction processes. For example, from 1991 to the present, YCM separation masters are prepared for every film. (2) And today, when a film is finished and output digitally onto a negative for release prints, another negative is assembled from the camera negative, the most pristine source, and that goes into cold storage.

Grover supervises a staff of about twenty-five people, six of whom are overseeing film laboratory and audio work full-time. Unlike other studio archives, Sony does not hand off preservation tasks to outside companies. Being a Film Person, Grover asks that for films a new negative be created, and fresh screening prints be prepared.

What impelled a big company like Sony to invest so much in preservation and restoration? Grover explained that the rise of home video taught most studios that their libraries had some value. In particular, executives were impressed by Ted Turner’s 1986 purchase of MGM for its library, which he could recycle endlessly on TBS. They realized that the libraries were genuine assets. Old movies enhanced the firm’s value (if it were to be sold, as many were in those days) and could be exploited through new media platforms, like cable.

The arrival of DVD made all the studios return to their libraries to make high-quality versions of their top titles. Now the high-definition format of Blu-ray will re-start restoration because of the leap in quality it offers.

Sony moved early, partly because it understood new media. When Sony bought Columbia Pictures in 1989, the Japanese executives envisioned a synergy between Sony’s hardware and a movie studio’s software. “One of the first things they asked,” Grover recalls, “was, ‘What’s the condition of the library?’” Soon afterward, Sony set up the first systematic collaboration between studio archivists and museum-based archivists. The Sony Pictures Film Preservation Committee included archivists from Eastman House, the Library of Congress, UCLA, MoMA, the Academy, and other institutions. In addition, Grover modeled Sony’s restoration policies on the exemplary work of legendary UCLA archivist Bob Gitt (whose work on sound restoration we’ve already saluted in another entry).

Digital restoration has been part of the Sony program. The 1997 restoration of Capra’s Matinee Idol (1927), from a Cinémathèque Française print, was the first live-action high-definition restoration from any studio.

Sony holds between 3600 and 5000 titles. It’s impossible to be more precise at this point because in hundreds of cases the rights situation is uncertain. But of the core library, about half to two-thirds of the films are restored. Crisp’s team is at work on about 200 titles at any moment! Many more are restored than warrant DVD release, but they may be available On Demand and via TCM, which has recently acquired cablecast rights to several older Columbia titles.

Restore, yes! But what, and how?

We’re grateful for preservation, but for cinephiles, restoration holds a special thrill. A “restored” Intolerance or Napoleon or von Sternberg movie gets us salivating. This year Cannes ran nine restorations on its program.

But what is a restoration?

We expect that a restoration will provide a film with a better-quality image or soundtrack than we’ve had so far. We often expect as well that a restoration will provide a more complete version of the title. Yet there are problems with both expectations.

First, who’s to say what the quality of the original is? Grover encountered this difficulty in restoring Funny Girl. It was released in the classic Technicolor dye-transfer process, usually considered the gold standard for color cinematography. He assembled five original Technicolor prints and all of them looked different. It turns out that Technicolor prints varied quite a bit. (3) The kicker was that Grover couldn’t make the new dye-transfer 35mm print of Funny Girl match any of these reference prints. That didn’t stop it looking fabulous when it premiered in LA.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

Moreover, it’s possible to “over-restore” a film. That is, by adding footage culled from many versions, the restorer may be creating an expanded version that nobody actually saw.

Original version? What does that mean? Paolo Cherchi Usai has reflected on this at length. (4) Is the original what the film was like on initial release? This is tricky nowadays for new titles, because as Grover pointed out, most films are “initially released” in several versions. Since Hollywood filmmaking began, different versions have been made for the domestic and the overseas markets, and often the overseas versions are longer. Sometimes a film opens locally or at a film festival and then is modified for release. Major films by Hou Hsiao-hsien and Wong Kar-wai have played Cannes in versions longer than circulated later.

Now suppose that the film was modified by producers or censors for its initial release somewhere. If you can determine the filmmaker’s wishes, should you restore the film to what she or he wanted it to be? That flouts the historical principle of getting back to what people actually saw. Consider the shape-shifting Blade Runner. Only now, twenty-five years after its release, has the U. S. theatrical version appeared on video.

Or what do we do when a filmmaker, after the release, decides that the film needs to be changed? Late in life, Henry James felt the urge to rewrite many of his novels, and the revised versions reflect his mature sense of what he wanted his oeuvre to be. Why can’t a filmmaker decide to recast an older film? Such was the case with Apocalypse Now Redux and Ashes of Time Redux. Since the later version represents the artist’s latest viewpoint, should that be the authoritative version?

Grover encountered a variant of this problem when he invited one cinematographer to help restore a film. The cinematographer’s own aesthetic and approach to his work had evolved over the years, so he started to tweak things in a way that was taking the look of the film to a level much different than the original achievement. Grover had to steer him back to respecting the film’s original look.

On the brighter side: Grover brought in master cinematographer Jack Cardiff to advise on the restoration of A Matter of Life and Death. Cardiff said that one scene needed a “more lemony” cast. Grover tried, but each time Cardiff said it wasn’t right. Finally, Grover confessed that he just couldn’t get that lemony look. Cardiff nodded. “Neither could I.”

Grover offers this nugget of wisdom: It is almost impossible to get an older film to look the way it does when it was originally released. The color will never look as it did, nor will sound sound the way it did. Film stocks have changed, printing processes have changed, technology in general has changed. Every version is an approximation, though some approximations may be better than others. Take consolation in the fact that even when the movie was in circulation, it may have already existed in multiple versions.

What do consumers want?

All archivists explain that compromises enter into the preservation process down the line. One of the revelations of Grover Crisp’s visit was the awareness of just how many of these compromises come into play, and how some of them are tied to what DVD buyers expect.

Many films from Hollywood’s studio era are soft, low-contrast, and grainy. Project a 1930s nitrate copy today, and though it will be gorgeous, it’s likely to look surprisingly unsharp. Things apparently didn’t improve when safety stock came along in the late 1940s; projectionists complained that those prints were even softer and harder to focus than nitrate ones. As recently as the 1970s, films were not as crisp as we’d like to think. I’ve examined the first two parts of The Godfather on IB Tech 35mm originals, and though they look sharp on a flatbed viewer, in projection the grains swarm across the screen like beetles. (I should add that many of today’s films also look mushy and grainy in the release prints I see at my local.)

But I think that DVD cultivated a taste for hard-edged images, perhaps in the way that music CDs cultivated a taste for brittle, vacuum-packed sound. It’s not surprising, then, that video aficionados are often startled when a DVD release of a classic movie looks far from clean. This is not always attributable to a film’s not being cleaned up to the fullest extent the technology allows. Some films are inherently grainy, gritty, or soft-looking. With the advent of Blu-ray and HD imagery for the home, those films’ look is often mistaken for problems with the transfer, or signs that the distributor didn’t care enough to spend the money to thoroughly make it new. “New” in this case means contemporary.

So there are compromises, according to Grover, that the studios are having to deal with:

What do do about a film that is really grainy? Do you remove the grain, reduce the grain, leave the grain alone? Everyone seems to have a different answer, and it often puts the distributor in a difficult situation. These are questions that will be answered over time, as the consumer gets used to seeing images in HD that truly represent the way a film looks.

Another compromise involves sound. “Now you’re getting to an ethical area,” Grover remarks. In restoring early sound movies, Sony removes only clicks, pops, and scratchy noises (while still keeping the original, faults and all, as a reference). Sound problems are compounded in films from the early 1950s. Many releases at that time were shot in a widescreen process but retained monaural sound. Yet avid DVD buyers want multitrack versions to feed their home theatres. “If it’s not 5.1, we get complaints.” So Grover’s engineers “upmix” mono, as well as two-channel stereo, to 5.1—though they strive to keep the 5.1 minimal and retain as much authenticity as possible. Not on every film, of course: often the original mono track is included on the DVD.

On the positive side, Sony held the original tracks for Tommy (1975), originally released in Quintaphonic. (Old-timers will remember that audiophiles were urged to upgrade to this, and some LPs were released in that format.) Grover was pleased that he could replicate the theatrical version’s 5-channel mix on the DVD. (More details here.)

Now for a hobby horse of mine. The 1950s-1960s standards for multichannel sound were not those of today’s theatres. Today’s filmmakers funnel important dialogue through the front central speaker. But in multi-track CinemaScope and other widescreen formats, dialogue was spread to the left and right speakers as well, and these were behind the screen. That meant that a character standing on screen left was heard from that spot as well. (Remember, these screens might be seventy feet across.) Long ago Kristin and I saw an original 70mm release print of Exodus (shot in Super Panavision) in a big roadshow house in Paris. The ping-pong effect of the conversations between Ralph Richardson and Eva Marie Saint was fascinating.

Today, however, it might be distracting. In a home theatre, where discrete tracks present sound from offscreen left or right, it would seem downright weird. Although Grover didn’t comment on this, it’s clear that the big-screen classics from the magnetic-track era are remixed for DVD to suit current theatrical and home-video standards. This makes it very difficult for researchers to study the aesthetics of sound design from that period. Even if you visit an archive, that institution almost certainly isn’t able to project the film in a multi-channel version. (5) Is it too late to ask DVD producers to replicate, on a second soundtrack, the original channel layout? This would be a big favor to the academic study of the history of sound, and some home-theatre enthusiasts might develop a taste for the old-fashioned sonic field.

Last questions

Q: Do Grover and his colleagues take notice of online chat about DVD releases?

A: Yes, because it’s important to know what many participants in those conversations want from a film’s release, and they may also know things (from a hardcore fan’s pespective) about a film that is useful to know. Grover’s staff members can learn about missing scenes and other variant prints. But sometimes the Net writers are working from incomplete information and can get things wrong. A fan fervently announced that one word was intelligible in the “original” version of a film but not on the DVD. Yet the theatrical release version muffled the word. It turns out that the word was audible in a remixed TV version, which the fan had used as reference. Likewise, one critic who found the color on the Man for All Seasons Special Edition DVD too vibrant was evidently using a VHS version as the reference point. (For what it’s worth, the color in the Man for All Seasons theatrical release I saw was extremely vivid.) And Grover and his colleagues never intervene in the online debates.

Q: Why do DVDs seem different from projected prints—often much sharper?

A: An original film frame, in camera negative, has more resolution than can be captured in a print. Most prints are a generation or two past the material that a DVD transfer uses, so they gain a certain softness. Granted, however, in making high-definition video masters sometimes the tools to sharpen and de-grain the image are overused.

In addition, it’s generally a good idea to get your home video display calibrated. Most home displays are way too bright, sometimes brighter than a theatre screen. If you darkened the room and had the display dialed down, DVDs would look more film-like.

Q: When will we get the Boetticher westerns?

A: It’s the most frequent question Grover gets asked. Soon, soon: A boxed set of restored titles is on the way.

Q: And what about all the Capra titles?

A: Sony plans to restore each of them. Columbia struck many prints of them, and so there is some negative wear. Some negatives no longer exist. On one title, Say It with Sables (1928), Sony has neither negative nor prints.

There’s a too-good-to-be-true backstory here. Capra had a ranch in Pomona, which upon his death was bequeathed to Pomona State University. After some years, people found in a locked stable his private collection of prints struck in 1939. The cache included Lost Horizon, You Can’t Take It with You, It Happened One Night, and the best-quality print of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington Grover had yet seen. There were also photographs Capra had shot of premieres and vacations. Thanks to the good offices of Frank Capra, Jr., Sony acquired the prints and used them in its restorations.

As for American Madness, Grover called it a “training film” for later Capra productions. The theme of faith in the little man, manifested in a bank run that tests a humane banker’s alliances in the community, points ahead to It’s a Wonderful Life and other films. Sony holds a complete soundtrack and a nearly complete original negative. UCLA held a complete nitrate print donated by the Los Angeles Parks and Recreation Department; evidently the film was screened in parks as public entertainment. That print wasn’t in good condition, but it allowed Grover’s team to fill out certain scenes. The nitrate print’s footage is noticeably lighter and grainier in a few places. American Madness wasn’t a digital restoration, but if it were done today Grover would probably use CGI to blend in the alien footage.

Talkies, with a vengeance

It was fine to see the film again; its brisk inventiveness held up. The gleaming and geometrical images of the opening, which acquaint us with the daily routine of opening the bank vault, might have come out of Metropolis. One helter-skelter montage sequence, complete with canted framings and chiaroscuro lighting, looks forward to Slavko Vorkapich’s delirious contributions to Mr. Smith and Meet John Doe.

The tactics of depth composition that we find in many 1930s movies reappear here, and the illumination has dashes of noir.

I especially like the dynamic pans that carry Walter Huston and Pat O’Brien in and out of the main office; I suspect that they’re cut together faster and faster as the climax gets near. And the huge set of the bank lobby, publicized at the time as the biggest set yet built on the Columbia lot, remains not only impressive but functional. It establishes a cogent geography to which Capra adheres strictly while filming it from a great variety of angles.

But this is not a treat just for the eyes. American Madness flaunts its mastery of emerging talkie technique. The rising action is accentuated by the steady increase in volume of the growing crowd in the bank lobby. The clerks’ scattershot morning chat in the vault is captured in microphone distances and auditory textures that suggest a hollow, sealed-off space. Hawks’ rapid-fire patter in Twentieth Century (1934) has an antecedent here, and at the same studio. The actors speak at a terrific clip, scarcely pausing between lines, and sometimes the dialogue overlaps. We even get competing lines, two or more speeches rattled off at once. (And did Hawks get the idea for His Girl Friday’s variants on telephone chatter from O’Brien working the receivers at the climax?)

In films like this, American movies talk American. Consequently, I’m inclined to regard as an in-joke the glimpse we get of a marquee that’s advertising another Columbia picture: Hollywood Speaks.

Thanks to Grover and Sony Pictures Entertainment for a wonderful series and an enlightening brace of talks. American Madness is available on the DVD set The Premiere Frank Capra Collection.

(1) Chris Horak has been head archivist at George Eastman House, the Munich Film Museum, Universal, and the Hollywood Museum; he’s now Director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Mike Pogorzelski is Director of the Film Archive for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Joe Lindner is Preservation Officer there. (Both are former Badgers.) Schawn Belston is Vice President of Asset Management and Film Preservation at Twentieth Century Fox. Paolo Cherchi Usai is Director of ScreenSound Australia, the national archive, and director of the recent film Passio. Kristin interviewed Mike and Schawn for this blog entry.

(2) YCM separation masters are made by copying a color film onto three black-and-white films. Thanks to filtering, these preserve color luminance at the different values of yellow, cyan, and magenta. Since these monochrome versions are not as susceptible to fading, they can be used for archival preservation. Combined, they can recreate the original color image.

(3) This confirms my impression when I’ve seen different Technicolor prints of the same title. You sometimes get this effect with a composite print, in which the color values change from reel to reel. Anecdotally, I’ve heard that Technicolor staff in the studio days would sort reels according to their dominant color (“That’s the yellow pile over there”).

(4) See Chapter 7 of Silent Cinema: An Introduction (London: British Film Institute, 2000). This book, incidentally, is a good introduction to the sheer fun of archive work. Others communicating the same enthusiasm are Roger Smither and Catherine A. Surowiec, This Film Is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film (Brussels: FIAF, 2002) and Dan Nissen et al., eds., Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002).

(5) This problem renders the activities of Britain’s National Media Museum in Bradford all the more important. There you can see classic films in a great many formats and sound arrays.

American Madness.

15 June: Thanks to Kent Jones for correcting a name slip.

19 June: Breaking News: Grover has just been promoted to Senior Vice President for asset management, film restoration, and digital mastering. Nice timing; wish we could say our blog put him over the top, butVariety explains that it was good old-fashioned talent. Congratulations to Grover!

Coming attractions, plus a retrospect

Invasion of the Brainiacs

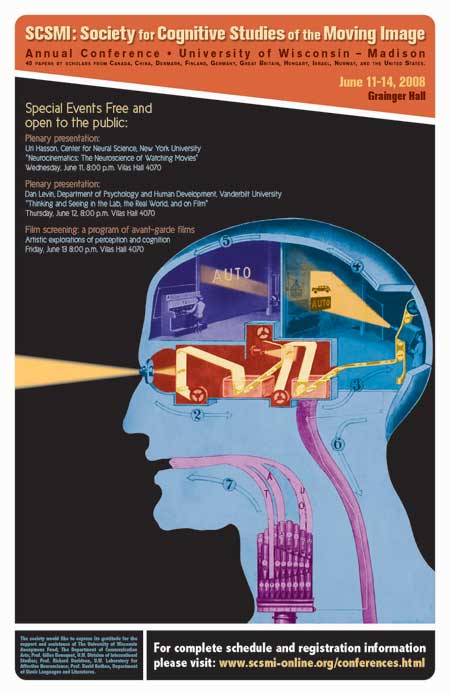

First, the event that will occupy us through next week: the annual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, a group founded in 1997. This year’s gathering brings researchers from Britain, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Turkey, Canada, China, and the Nordic countries, as well as many from the U. S. The meeting is here in Madison, from 11 to 14 June.

In over forty sessions, researchers will be talking about how we respond to movies, TV shows, and videogames. How has digital imagery changed our experience of cinema? How does film music enhance our emotional response to the story? How do films guide our visual attention to one part of the screen, and how much do viewers differ in this? How do we respond when movie characters behave inconsistently?

I’ve already blogged and bragged about our event here, but now I want to highlight four attractions. If you’re in or near Madison, you might want to stop by; and in any case, you might want to check the links mentioned below.

For some years Professor Uri Hasson of New York University’s Center for Neural Science has studied how the human brain responds during film viewing. Using fMRI techniques, he has discovered that Hollywood films, such as those by Hitchcock, have created remarkably similar responses across a variety of viewers. Art films, he says, may require just as much concentration, but they will elicit less convergent reactions. He’ll present the fruits of his research on June 11. You can learn more about Uri’s research here.

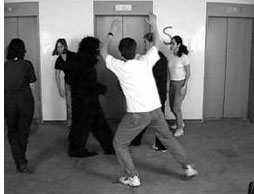

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

NB: 12 June 2008: In fact, the gorilla-suit experiment was conducted by Dan Simons, not Dan Levin. The last link takes you to Simons’ article. Both Dans work in the area of attention and “change blindness,” and they have collaborated on several projects. I apologize for the error.

There is a registration fee for the conference’s day events, but these evening lectures are free and open to the public. Each begins at 8:00 PM and will be held in 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Avenue.

The final night of the conference is devoted to a screening of experimental and avant-garde films that provoke questions about how we respond to cinema. There will be a discussion of them afterward, which will include two of the filmmakers, Joseph Anderson and J. J. Murphy. This screening, open to the public, starts at 8:00 PM in 4070 Vilas.

During the conference, one event is devoted to a discussion of Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Motion Pictures. This book is a remarkable effort to mount a systematic philosophy of film, TV, and related media. It’s full of provocative claims (e.g., that cinematic movement isn’t an illusion) and nifty examples. Noël is a polymath, with two Ph. D.s and more books and articles than anybody, including he, can count. Four other scholars will criticize some aspect of the book’s arguments, and Noël will respond. (One of those critics, Lester Hunt, is a philosophy prof here who maintains a wide-ranging website and a blog that often touches on film.) There should be some fireworks.

There are other brainiacs coming, many of them pioneers in this area: Joe and Barb Anderson, Murray Smith, Torben Grodal, Patrick Colm Hogan, Carl Plantinga, Paisley Livingston, Sheena Rogers, Dan Barratt, and Tim Smith (aka Continuity Boy), and too many others to include here. In all, I’m proud of what our local team, with the energetic Jeff Smith as point man, has accomplished in setting up this jamboree.

As regular readers know, I think that cognitive research into cinema holds great promise. It brings together a group of scholars from different disciplines who want to understand, in an empirical way, how movies work. The field is very young, and it’s not the only way to go; but it has a lot to contribute to our understanding of media, and maybe our understanding of the mind too.

Up to now SCSMI has been quite an informal group, but now we have a more systematic organization. We have officers, bylaws, and a sense that our research is coalescing around key ideas, about which there is lively and congenial disagreement. And, because there are more people who want to get involved, we’ll start meeting every year. The 2009 gathering is slated for Copenhagen.

I hope to dash off a blog entry in medias res. We’ll also do our best to introduce our colleagues from overseas and from the Coasts to the glories of brats, cheese, beer, and of course The House on the Rock.

By the way, you might want to check on this cognitive scientist, who claims that every one of us can see into the future (but only a little bit).

Kristin and the Comic-Book Guys (100,000 or so)

Speaking of gatherings of like-minded individuals, TheOneRing.net people have invited Kristin to take part in their panel on the upcoming Hobbit project at Comic-Con in San Diego, on Friday, July 25 at 10 am. She hopes to blog from among the multitudes.

A new website and a nervous DVD

There’s a new and attractive website up and running. Sponsored by the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, NYC, Moving Image Source is a vast project packed with links, research data, and essays about films both classic and contemporary. The first posse of writers includes Michael Atkinson, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Ed Sikov, Melissa Anderson, and other luminaries. The topics range from Andy Warhol and Howard Hawks to Werner Herzog (an interview). Steered by Dennis Lim, this is bound to be an essential watering hole for everybody interested in film history and criticism.

Speaking of film history, an important film is coming to DVD. Robert Reinert’s 1919 Nerven, which I wrote about in Poetics of Cinema, has been restored by Stefan Drössler and his crew at the Munich Filmmuseum. This is one of the strangest movies of the silent era. The plot, as Chris Horak points out in his accompanying essay, is steeped in Spenglerian melancholy, reminding us that Expressionism could be politically conservative as well as revolutionary. The visuals are at once monumental and unstable, like boulders teetering over a precipice. I try to analyze them in another contribution to the DVD booklet. Drössler has contributed an essay on the process of restoration.

Nerven was a box-office fiasco and never achieved the fame of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In a way, it is more disturbing than that official classic because Reinert’s alternation of frenzy and somnambulism takes place in a more or less solid world, like ours. Frantic scenes of street fighting mix with brooding images of a bourgeoisie sliding into religious possession or straight-up lunacy. It is not every day that you see a movie that begins with a man throttling his wife and then lovingly refilling their parakeet’s water cup. If you’re a fan of wild deep-space imagery way before Citizen Kane (as above), this one’s for you. And yes, it will have English subtitles.

Nerven will be available later this summer from the Filmmuseum’s shop. It joins an abundance of other fine DVD titles, such as Borzage’s The River and a collection of Walter Ruttmann’s works.

Retrospect: In Europe they do things differently?

Because we see a very thin slice of foreign-language cinema, audiences underestimate the extent to which European films often imitate Hollywood. Surely the cultures of the great continent would never stoop to the crassness of our movies? A trip to any multiplex in Paris or Berlin would probably disabuse people of this notion. The current instance is the reigning French hit Bienvenue chez les ch’tis (Welcome to the Sticks), apparently a fish-out-of-water tale that would induce groans from our intelligentsia.

Kristin has already written about this phenomenon here. I found some supporting evidence last week while scrabbling through an old folder for our Film History revision. It was a 2002 pamphlet from the Filmboard of Berlin Brandenburgh GmbH, a publicly limited company coordinating German state funding. The text laid out a set of guidelines, in English, for productions that the Filmboard would support. After explaining that the judges must consider financial return as well as cultural factors, the guidelines insist that the quality of the screenplay is of paramount importance. What makes a good screenplay?

The success of a film decisively depends upon whether the audience can engage enthusiastically with the actors on the screen. An audience looks for strong central characters whose fates it can identify with. The hero or heroine should have goals and needs and should have an emotional effect on an audience. Further dramaturgical criteria:

There must be a concrete goal, which at the end of the story is either reached—or not.

There should be a risk involved for the central character in not reaching his/her goal.

The goal is perhaps difficult to reach, and the struggle to do so should bring the central character into conflict. The audience sympathizes with the story when, for example, the hero or heroine follows the wrong goal, makes mistakes, or experiences a crisis.

This sounds easy to understand. But writing screenplays is more complex.

*The central character should have subconscious needs. He/ she should lack an important human quality and only gradually experience this for him/herself.

*At the end of the story the central character should come to know his/her unconscious needs and gain a satisfactory recognition about him/herself and life in general, which can be formulated in the emotional subject matter of the film.

*The central character should undergo a process of development, as characters that do not develop are boring. Moments of decision in stories are the key for good character development.

The passage lays out a lot of what U. S. screenplay manuals have been asserting for decades (notions that Kristin and I have analyzed in various books). This is still more evidence that the Hollywood model, with its goal-oriented chain of causes and effects and its protagonist who improves through a “character arc,” holds sway far beyond our own shores. Whether it should be so widespread is another question, but for Kristin and me, this template or formula is a bit like the sonnet or the well-made play: a form that can yield results good, bad, and indifferent. The point is to take the form seriously enough to understand what makes it work.

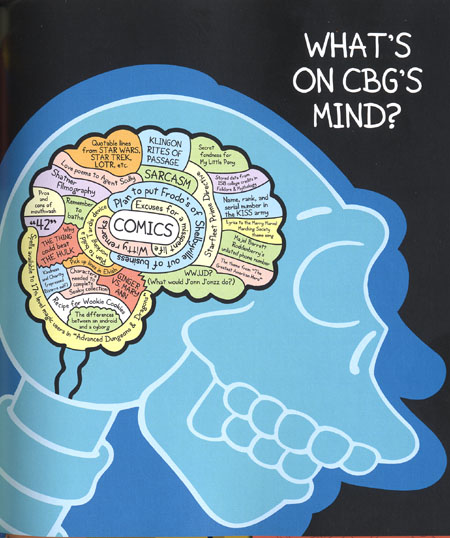

From Comic Book Guy’s Book of Pop Culture (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), n.p.