Reflections in a crystal eye

Wednesday | June 4, 2008 open printable version

open printable version

Whew! After many months of work, we finally sent in our revised third edition of Film History: An Introduction. Elsewhere on this site you can read about its earlier incarnations, and we expect to say more about it as it approaches publication in February 2009. But writing this tome isn’t as fast as webposting, for sure.

So how did we celebrate? A meal out and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (after about sixteen trailers for Paramount and DreamWorks releases). As with Beowulf and Ratatouille, we talk/ write about it together, but not in dialogue form. Kristin gets her time at the podium, then David. And there are of course spoilers.

Don’t even mention pyramid power

Kristin here:

I enjoyed the first half or so of IJatKotCS, but gradually it occurred to me that it wasn’t really building. It was violating the basic law of suspense films, which is to make your villain threatening and the things at stake important. Sure, in the B-film serials that inspired the Indiana Jones films, the premises are ludicrous. But so are the sets and the acting and just about everything about them, because they were so cheaply and quickly made.

With Indiana Jones, these adventure films become high-budget productions with the biggest, best special effects that money can buy. They star actors who have won or been nominated for Oscars. Moreover, the scripts don’t imitate the clichéd, bare-bones plots of the Bs. These are complicated stories that not only move ahead at a pace undreamed of in the serial days, but they toss in many little details and in-jokes in the backgrounds. With Steven Spielberg directing, one expects the non-stop thrills to also make sense, at least in a casual way.

Eventually I became distracted by the fact that certain things stopped making sense to me. Most obviously, what is at stake with that crystal skull? The Soviets want it, and Irina Spalko informs Indy that it’s to make a psychic weapon. Hmmm. And what is that, exactly? She doesn’t explain, and it’s clear that the Reds don’t know enough about the crystal skull to really understand what they’d do with it. In fact, they need Indy to help them every step of the way, and after a certain point his expertise becomes irrelevant, and they’re all dependent on Prof. Oxley to lead them to the kingdom.

I suspect most people’s reaction to her “psychic weapon” announcement is to think she’s nuts, deluded. The skull has apparently driven Oxley crazy (John Hurt playing loony as only he can do). Or did that just happen because he was locked in a very grim Peruvian insane asylum? We’re allowed to go on wondering if the skull has any psychic powers until the scene where Indy gets strapped in a chair and forced to stare into the eyes of the skull. The fact that he is so profoundly shaken by the experience finally shows that the object does have some sort of psychic effect.

But how could it be a weapon? Earlier an atomic bomb has gone off, and that’s engineered by our side, the good guys. How could a psychic weapon top that? Are the Russkies going to strap all the American soldiers one by one into chairs and make them stare into the skull? Talk about creeping Communism!

Spalko can’t explain it to us, since she is trying not only to get the skull but to figure out its secrets. Up to the very end, she says “I vunt to know.”

Of course, ignorance on the part of the villains need not be a problem. In Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Nazis didn’t know what power the Ark of the Covenant contained until it was too late. At least there, though, we understand from early on that the Ark really is dangerous in what is presumed to be a physical way. Moreover, there the villains were Nazis. We know what horrors the Nazis perpetrated on the world, and we and our allies actually went to war with them. With the Soviets, it was largely a long, tense brinksmanship. Luckily we never found out what a war with the USSR would be like. Today, well after the Soviet Union imploded on its own, the paranoia over reds in our midst seems quaint in an adventure film. Early on Indy and his department chair (Jim Broadbent) lose their jobs, and in a glum scene they deplore how Americans’ irrational fear of Communism has caused it. Yet soon after we discover that there really are Communist spies looking to steal America’s secrets. A mixture of tone, to say the least.

In Raiders, the Nazis seemed to be part of a worldwide network of spies. Spalko seems to be operating with only the group of soldiers that accompanies her. She never reports back to “headquarters.” One wonders if maybe Khrushchev sent her off on a wild-goose chase to get rid of her for a while.

Professor Jones Flunks Archaeology 101

One thing that distracted me and that seems to vitiate the notion of real threat in IJatKotCS is the fact that it’s based on hoaxes and wacko theories. At least there’s some archaeological evidence that elements of the Bible have their bases in real events. There may have been some sort of Ark of the Covenant and a Holy Grail. But to base the premise of the film on Chariots of the Gods (Erich von Däniken, 1968) and crystal skulls gives it a certain ludicrous quality that wasn’t there in the earlier films’ premises, wild though they were.

The film flits lightly past the nuts and bolts of how that Kingdom of the Crystal Skull came to be. Presumably, as in Chariots of the Gods, the aliens arrived and traveled around giving instructions on how to build such things as pyramids and Easter Island statues. The room in IJatKotCS where artifacts from Egypt, China, and other ancient cultures are gathered implies that long ago the aliens visited the earth, collected examples of the fruits of their teachings, and … instead of putting them in their space ship to take home, they left them in a chamber that would be crushed when the Kingdom built over the space ship is destroyed. (Don’t get me started on where the ancient Peruvian warriors who pop out of the walls to briefly chase the good guys came from.)

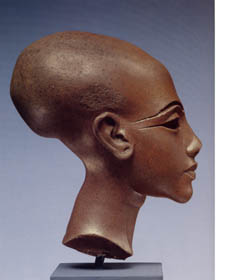

Then there are the skulls. The “real” crystal skulls held in museums, most notably the British Museum one referred to in the film, have been shown to be objects made in modern times, probably within the past 150 years. Those skulls, however, are of normal proportions. The ones in the movie are strangely elongated. Head-binding, Indy offhandedly explains.

There’s another apparent source for this, one that I’m familiar with. The pharaoh Akhenaten, famed equally for inventing monotheism back in the 14th Century BCE and for being married to Nefertiti, has been the subject of much far-out speculation. The art of his era, the Amarna Period, shows his family with strikingly elongated skulls, as in the quartzite head of the statue of a princess at the left. Head-binding, various medical syndromes, and pictorial stylization have been posited. One imaginative claim has it that Akhenaten and his family actually were space aliens.

There’s another apparent source for this, one that I’m familiar with. The pharaoh Akhenaten, famed equally for inventing monotheism back in the 14th Century BCE and for being married to Nefertiti, has been the subject of much far-out speculation. The art of his era, the Amarna Period, shows his family with strikingly elongated skulls, as in the quartzite head of the statue of a princess at the left. Head-binding, various medical syndromes, and pictorial stylization have been posited. One imaginative claim has it that Akhenaten and his family actually were space aliens.

In fact, we still have no convincing explanation as to why this style occurred in Amarna statuary. (The Egyptian expedition I work on is at Amarna, the ancient city built by Akhenaten, and I work with statuary fragments found there.) The film, of course, doesn’t bring Akhenaten into it, though I think I did spot a photo of the seated statue of him in the Louvre on the chalkboard of Indy’s classroom. Akhenaten is a figure of considerable interest to New Age enthusiasts. Every now and then a group of people in white robes and turbans actually come to Amarna to worship in the ruins of the temples.

The ancient-aliens-visited-earth premises and the less explicit references to Amarna are woven in with El Dorado and with the Roswell myth that modern aliens visited earth. There’s even a nod to the Alien Autopsy film that David discussed in an entry on “Film Forgery.” The film also brings in the mysterious Nazca Lines, the shapes carved into the earth over which Indy and Mutt fly as they arrive in Peru. Some have claimed that the lines are runways for alien ships, and I think the film tries to imply that. But why would a flying saucer that takes off (and presumably lands) vertically need a runway, let alone one shaped like a monkey or any of the other complex figures that survive today?

The silliness that hovered near the edge of plausibility in the earlier films has crossed that line. At least the first and third movies made an effort to ground their mcguffins in real history and real places. Tanis, where a lengthy portion of Raiders takes place, is a real set of ruins in Egypt. In Last Crusade, Indy and his father can spar by showing off their knowledge of actual or apparently actual history. (I’ll leave it to the comments on the “goofs” page of the Internet Movie Data-base to deal with the transfer of the Mayans from Central America to Peru.) Each of those films was a race to prevent a lethal object falling into the hands of those who would both desecrate it and use it for evil purposes. Crystal Skull is a race to figure out what the apparently dangerous object is, given that the only person who knows, Oxley, is conveniently rendered unable to explain it.

Indy and his group win the race and get to the chamber ringed by crystal skeletons first, so that Spalko is effectively defeated before she gets there, though she doesn’t know that yet. Which brings me to the last thing that baffled me. Why, if the thirteen skeletons were separate beings, as they are depicted in the wall paintings, do they merge into one before being restored to life? Apparently the space ship was waiting to depart because, unlike in E.T., the aliens didn’t want to leave one of their number behind. But is there more than one alien left at the end to depart in the huge ship? Does the ship wait simply because it brought only one passenger, and that passenger can’t start it moving until it gets its head back? Yet surely there would have had to have been a crew to help build all those ancient wonders and bring the evidence back to the “kingdom.”

Maybe a second viewing would clear all this up, but the old serials didn’t need second viewings to be understood—and neither did the earlier Indy films.

The Spielberg Touch

DB here:

Kristin’s critique reminds us that the classic Hollywood structure demands a linear logic, but not a plausible or even particularly deterministic one. Like other action films, Crystal Skull follows the template she pointed out in her New Hollywood book: four parts, the first three running about half an hour and the climax somewhat shorter, the whole capped by an epilogue. It goes to show the difference between plot structure and the events of the fictional world that structure presents. The structure can make preposterous or puzzling chains of action seem acceptable—especially if it whisks them along.

I was taken, as usual, by Spielberg’s brisk direction. In the last decade he’s had a remarkably hot hand. Amistad, Saving Private Ryan, A. I., Minority Report, Catch Me If You Can, The Terminal (much underrated, I think), The War of the Worlds, and Munich are very strong movies. For all their faults (sometimes those slippery endings), they would be enough to establish a younger director at the very top. So I was watching for what I take to be The Spielberg Touch.

His staging is still solid and resourceful. When he has to let people talk, he moves them around the set, avoiding those dreary passages of stand-and-deliver that most directors today resort to. (Check the dialogue scenes from The Matrix Reloaded.) In a soda fountain, he lets your attention drift from the exposition between Mutt and Indiana to the teenyboppers behind them, to the point where I was distracted from Mutt’s explanation of those muddled plot premises Kristin points out.

Spielberg has said that he favors lengthier shots than are typical today. That’s true in most of his dramas and comedies, but here the cutting is fast. The shots average 4.6 seconds by my count, which is about the same as the other Indiana Jones films (1). But whatever his shot length, Spielberg doesn’t resort to choppiness, the sort of image-snatching that typifies today’s mainstream cinema. He’s one of the few filmmakers working today (Shyamalan is another) who tries to give most shots a distinct arc—a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Granted, most shots in any movie will develop or progress, even if a character just steps forward or raises an eyebrow at the end of a spoken line. But Spielberg enriches his shots in the way that the old adage suggests: The only problem of direction is to prepare the audience for what is going to happen next.

The ambitious Spielberg shot starts with something that links precisely to a previous shot, then develops a visual or narrative premise of that, then ends with a firm point of information that carries us into the next shot. His main tools for building the shot are are spatial depth and camera movement.

Linking the shots, in multiple ways

In War of the Worlds. the protagonist Ray is hurrying toward the center of his neighborhood, where people are gathering. He passes a garage, where the mechanic Manny and his assistant are trying to fix a burned-out ignition. As Ray strides by, he suggests changing the solenoid, and Manny agrees. This becomes important later, when Ray will seize the vehicle because it’s the only civilian car that’s working.

Spielberg binds his shots together in this way. The end of the first shot shows Ray, along with others, hurrying to the left. Cut to a shot from inside the garage, with a silhouette in the foreground bending over a car’s engine. Ray becomes visible in the distance.

Ray’s appearance and reappearance link the shots, while Spielberg’s composition has prepared us for a dialogue between Ray and the man, as yet unseen, in the foreground. Cut to a moving point-of-view shot of Manny rising and turning to Ray (us) and explaining what has happened.

Reverse shot of Ray, still trotting along, over Manny’s shoulder as he suggests changing the solenoid. As he goes on, cut: The moving shot now detaches itself from Ray’s point of view and shows Manny ordering his assistant to change the solenoid. The assistant bends over the engine.

Cut to another driver bent over his engine. This reiterates the story point that everybody’s car has stopped, but it also echoes the end of the last shot (and the beginning shot of Manny in silhouette). Crane up slightly to pick up Ray walking leftward in the distance, an echo of the foreground/ background interplay of the Manny/ Ray shot.

How to develop this shot? We follow Ray, along with a skateboarder, to the intersection, where Spielberg introduces a new element. The shot gradually brightens and as Ray moves to the major intersection, rays of light wash out the image.

The next shot will repeat this pattern, from darkness to rays of light, so that the following shot can start with a burst of light that envelops Ray.

Then a new story component, involving Ray’s two buddies, comes in from the foreground. Their conversation with Ray will get a tracking shot devoted to it, but it will end with a story point….and so on.

Spielberg maps his story points quite precisely onto the beginning/ middle/ end of his shots so that they link smoothly with one another. Each camera movement or depth pattern leads to a distinct revelation, sometimes a fresh one, sometimes an expansion or specification of information we’ve already received. This is one reason he uses so many matches on action, even in simple dialogue scenes. The last bit of one shot can serve as the premise for the next if its movement can be carried over the cut.

Something extra between the shots

Sometimes that last bit is a surprise. Something pops up in the foreground or on the frame edge, or the camera slides over or back to reveal something that impels us toward the next shot. In Crystal Skull, Indy swiftly empties a refrigerator, hurls himself in, and as he yanks the door closed it swings toward us revealing the label LEAD LINED before it shuts . . . and the atom bomb goes off.

Sometimes the end-of-shot payoff sets up a motif that itself will be paid off later. When Ray runs from the spindly, towering alien vehicle, he ducks around a corner and halts, but Spielberg’s framing gives us time to see the fleeing crowd reflected in a shop window. Spielberg introduces a new motif when Ray, stepping out from behind a car, is standing near a man taking a photograph.

Shortly, another reflection, this time supplying both action and reaction: the alien walker seen in in a shop window as people inside stare at it. And again we have photography, when, in a shot echoing the earlier one, a man upstages Ray and films the creature’s advance with a video camera.

At the climax of this string of shots, the creature’s approach is again given in reflection, only now it’s Ray standing alongside it (bringing together two elements previously kept apart, Ray and the reflection of the aliens). After the creature sends out its death vibes, the video camera falls into the shot, showing us, in its own version of reflection, the fleeing crowd–the subject of the first reflected image we saw.

Following the end-of-shot hooking principle, the image on the video screen will link to the next shot we see of the people fleeing in panic. My larger point is that the braiding of motifs—reflections, photography—ends with them knotting together in a single image, the shot of the video camera. This sort of patterning was something that Eisenstein both theorized and practiced; he called it “wickerwork” montage construction. Spielberg has, in the context of American action pictures, rediscovered how powerful it can be.

He brings the same shot-by-shot fluency to dialogue scenes. A small scene in The Terminal shows Victor tussling with an official over his passport. Spielberg sets it up with our old friend, over-the-shoulder shot/ reverse shot, but he gives us two bits of business: The official slipping Victor’s plane ticket into a pouch, and Victor grabbing back his passport.

Match on action as the official continues to put away the ticket and demands the passport. A change of angle to a profile view adds a little amusement to the scene.

In reverse-angle Victor warily extends the passport. Cut back and forth as the two men tug on it, the action accentuated by a squeezing sound.

The official wins, and he slips the passport into the pouch. Spielberg gives us a variant on the reverse-angle on Victor, adding a fast rack-focus that resolves the scene with a neat snap.

In making even small gestures engage us in a visual flow that is rhythmically arresting, Spielberg displays craftsmanship of a high order. Despite his influence on a generation of filmmakers, this level of skill is rare today. If this be Storyboard Cinema, make the most of it.

I’ve already gone on too long, but I want to suggest that this cunning arc of interest, of doling out story points within shots and across cuts, also quickens his chase scenes. We say that his action scenes are clear, and partly that comes from his patient willingness to design long shots and overall views that keep us oriented. But these sequences also draw us in because shot by shot they build carefully, with little transitions—a glance, a gesture, a shift of focus or framing—that crisply link to what we will see next.

I saw a little of this crispness and fluidity in the pursuits of Crystal Skull. They can’t help but seem fairly stale, since Spielberg is competing with himself and with directors who learned from him (e.g., John McTiernan in Die Hard). And as per convention, bad guys have bad aim and they run out of bullets at an awkward moment. Yet the chases still piled complication upon silly complication, from ants and rapiers to cliffs and waterfalls, often set up at the end of one shot and paid off at the beginning of the next, which also sets up another.

The Spielberg Touch includes some visual wit. Everyone remembers the shot from Jurassic Park showing the T-Rex pursuing the Land Rover, as reflected in a side mirror saying “Objects in mirror are closer than they appear.” I think the habit goes back to Jaws, possibly still Spielberg’s best movie: the billboard with the graffiti and of course the rise of Bruce from the sea as Brody is scooping chum over the side. To make audiences gasp and laugh at the same time is no mean feat.

Crystal Skull seems to display less of this wit. The glimpse of the Ark of the Covenant in the warehouse and especially the montage of a squeaky-clean suburbia about to be vaporized were typical Spielberg, but I wanted more. Maybe a second viewing will show me that more.

But I was glad to see the Roswell ingredient here, and to learn that Indy did his duty in July 1947, even if he wasn’t there for the alien autopsy.

Faces and light

Finally, a little image-cluster that recurs in Spielberg’s work intrigues me. It was in Close Encounters that I first noticed his fascination with linking faces and beams of light. In that movie people just watch, transfixed by the luminous aerobatics of the vagrant UFOs and then eventually by the four-alarm light show pumped out by the mother ship. Then there’s the iconic image of Elliott staring at E. T.’s luminous digit, and the radiance of the church in the above scene from War of the Worlds.

Light beams can be punishing too. They melt faces in the first Raiders and blow a woman’s face to bits in War of the Worlds. They’re back again here—sprayed out by an alien intelligence and infecting the bad guys. Poor Irina Spalko, played with pelvic-thrust relish by Cate Blanchett, absorbs the rays through her eyes before detonating in one of those Armageddons that are obligatory in today’s megapicture. (Why do blockbusters have to include literal blockbusters?)

Maybe a critic in the vast Spielberg literature has discussed this dynamic between uplifting light and damning light, the enthralled face and the blasted one, characters spellbound by light and doomed by it. My hunch is that it will take us into religious and/or New Age territory.

(1) I get 4.3 seconds for Raiders, 3.5 for Temple of Doom, and 4.7 for Last Crusade.

Minority Report.