Archive for September 2008

13 days without movies? Not desirable, but possible

DB yet again:

Our road trip started back on the twelfth of September. We drove to Iowa City and ate at our grad school hangout, Hamburg Inn no. 2. (We even remember Hamburg Inn no. 1, long since vanished.) We pressed on through Nebraska to Denver, for a meeting of the Amarna Research Foundation, which helps support the Egyptian expedition on which Kristin works. She gave a presentation about the unique composite statuary of the Amarna era containing a new hypothesis that Barry Kemp, head of the expedition, found promising. After enjoying the hospitality of ARF president Bill Petty and his wife Nancy, we visited the Rocky Mountain National Park.

After a long day’s drive west, we overnighted in Elko, Nevada, where we learned that Barack Obama was scheduled to give a stump speech the next morning. We hung around and joined an enthusiastic group from all over northern Nevada to hear what he had to say.

After shaking hands with Barack, we moved on, rolling through Utah and into Oregon and Crater Lake National Park. Then up the coast highway to Seattle, where our nephew Sanjeev works for Microsoft and lives with his wife Maggie. We did some nifty touristic things in Seattle, and then with Sanjeev and Maggie we pressed on to Vancouver for its annual film festival.

During our westward passage through Grand Island (neither grand nor apparently an island), Craig, Elko, Klamath Falls, Coos Bay, Tillamook, and Tumwater, we saw many intriguing things. There was, for instance, the perfect rainbow in the bleakly beautiful northwestern Nevada desert.

In a little Colorado town, we found the toilet seat with fishing lures embalmed within.

In Snoqualmie Falls, Washington, while we downed burgers and malts at the Candy Factory & Café, four red-hot mamas came in and spontaneously started singing 1940s swing, Andrews-sisters style.

Yet such roadside attractions can’t compensate for our trip’s biggest drawback. We didn’t see a single complete film, not even on the free HBO available in motels. We used our late evenings to wolf down Subway subs and scan the Internets for news of lipstick, pigs, and less important things like the free fall of the U. S. economy.

Still, even without watching movies we did run across many traces of cinema. So don’t worry: This isn’t a travel entry, but rather an offhand effort to note the ways film keeps crossing our path, sometimes in surprising ways.

Movies everywhere

For instance, Bill Petty, an ardent Egyptomane, has created a home theatre unlike any other. The Pharaohs surely look with envy on this screening room.

In this venue, Bill showed us his home-made mashup of the Lon Chaney Phantom of the Opera with the Andrew Lloyd Webber score. That was the closest we got to movie viewing on the trip.

Also in Denver, we ate breakfast with Diane Waldman, old friend and film prof at University of Denver, and her husband Neil. We of course wound up in a restaurant with movie posters.

Passing through Vernal, Colorado, we spotted the most austere multiplex we’d ever seen.

Then there was Donna Kupp’s Books in Reedsport, Oregon. Donna has an excellent collection of classic paperbacks and magazines.

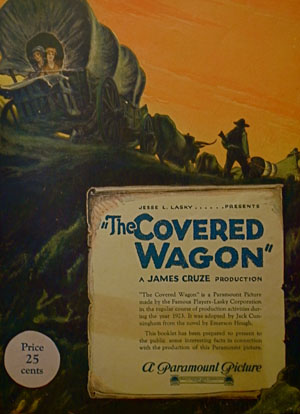

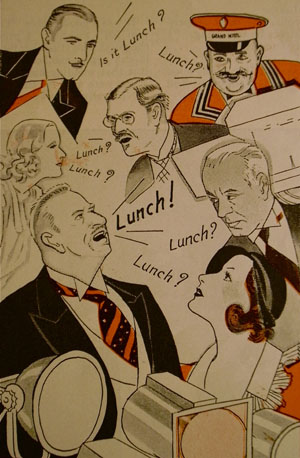

The high points of our purchases were an original souvenir program for The Covered Wagon and a pretty issue of Photoplay from 1932, which featured a gossipy story about the making of Grand Hotel.

The ladies’ big-band quartet wasn’t our reason for stopping in Snoqualmie, of course. You know why. The town was the shooting location of Twin Peaks. Hence this inevitable snapshot.

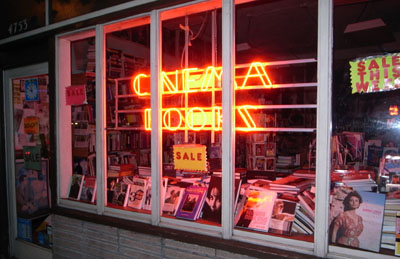

In Seattle, we discovered Stephanie Ogle’s outstanding Cinema Books on Roosevelt Way, N. E. This store is stuffed to the rafters with film items old and new–books, magazines, posters, and stills. Kristin even autographed some copies of her books.

We picked up several items there. Earlier that day, we visited Paul Allen’s lively Science-Fiction Museum. Sumptuous exhibits, but we weren’t allowed to photograph them. We did, however, get a chance to study a clone of the alien from The Day the Earth Stood Still.

As usual, a trip to an art museum provokes me to think of cinema. You don’t need much nudging to see this Rubens prototype for a Last Supper ceiling as a steep low-angle Welles or Hitchcock shot.

Less obviously, Abraham Janssens’ Origin of the Cornucopia (c. 1619) suggests a wide-angle lens at work. The three dryads stuffing the cornucopia are monumental, and monumentally skewed.

The stretched arm of the dryad on the left and the tipped knee of the one on the right seem to bulge right out of the picture plane. Check the hands, which thrust out of the picture and loom larger than the ladies’ heads. In particular, though you can’t see this in reproduction, the thumbnail of the figure on the right is a little blob of paint sitting on the painting’s surface, accentuating the sense that this hand is pointing right at us. Such images remind us that 2-D and 3-D are not so easy to keep distinct.

Our road trip confirms that movies are everywhere, waiting in the corners of our lives, ready to be activated with barely any prompting. Nonetheless, these are all merely teases, snacks making us eager for the banquet to come in Vancouver.

For Jim Emerson: Barbara Stanwyck, from Photoplay (Oct 1932).

They’re looking for us

DB again:

Perhaps you consider Music and Lyrics (2007) a bit of fluff. Bear with me. Apart from offering an ingratiating parody of 1980s music videos, which at the end gets replayed as a parody of 1990s Pop-Up Video, this movie provides a nice example of a technique that film viewers tend to enjoy.

Alex Fletcher, a has-been pop singer, gets a chance to revive his career by writing a love song for Cora Corman, current goddess of teenyboppers. Alex can dash off a melody but he needs a lyricist. His agent has advised him to try to collaborate with the “very hip, very edgy” Greg Antonsky. Their first meeting doesn’t go well. Greg’s lyrics, rhyming witch and bitch, don’t suit Alex’s more romantic style, and Sophie, Alex’s plant-tender, keeps interjecting sweeter lines. After first eyeing Sophie lecherously, Greg decides she’s a simpleton. He dashes out, condemning Sophie and Alex as sentimental fools: “You people disgust me!”

As written, the character of Greg the lyricist is only mildly funny, but the insert shots of actor Jason Antoon raise the comedy thermostat. With his lowered brow and glaring, slightly unfocused eyes, Greg tries to play the badass, but his aggressiveness comes off as egotistical pettiness.

The cutting relies on single shots of each character, in keeping with today’s style of intensified continuity editing. This ensures that we track every character’s facial expression. When Sophie first interrupts, Greg glares, then lolls his head backward; his time is too important to spend with these losers.

In all, Greg is onscreen for about three minutes, and the plot continues without him.

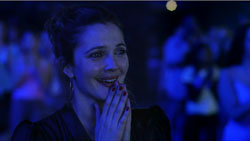

Eventually, Alex and Sophie break up because Alex is prepared to let Cora turn their song into a sleazy number. The climax comes at Cora’s concert, when Alex appears onstage and sings a tune he composed for Sophie: “Don’t Write Me Off.” At the song’s close, we get a shot of him at the piano followed by several reaction shots in the audience, with Sophie’s close-up favored.

After a backstage reconciliation between Alex and Sophie, the film’s second plotline is resolved. Cora performs the number she asked the team to compose, but it’s played the way Sophie had wanted. The up-tempo melody brings Alex and Cora onstage together and then, as the third verse begins, ties together the secondary characters in a series of reaction shots. We first see an African-American backstage handler, whose vigorous swipe of his arm launches a string of smiling responses.

We get shots of Alex’s agent and his daughter, then Sophie’s brother-in-law and his son, and Sophie’s sister and their kids.

Their responses celebrate both the romantic couple’s success and the sincere emotion that the song elicits. This aura of good feeling is confirmed negatively by one more reaction shot.

It is the sort of satisfying surprise that Hollywood often trades on. After being offscreen and out of mind for eighty minutes, arrogant Greg returns. We didn’t see him come to the concert; we didn’t know he was there; we had likely forgotten he existed.

This shot is agreeable because it keeps Greg’s sourness consistent. A more kindly film would show him smiling begrudgingly, won over by the authentic sweetness of the music. But instead he mimics blowing his brains out and lolls his head back as he did before.

Greg’s appalled reaction to the song confirms our initial judgment of his character and our sense of the song’s unpretentious sincerity.

If you’re like me, this unexpected four-second shot makes you laugh. The director, Marc Lawrence, has followed tradition by including humor in a scene of high sentiment, not diluting the happy tone but reinforcing it. Call it corn, hokum, or tosh; claim that it hits below the belt. I won’t disagree. But the mixture of laughter and sentiment works on us like a reflex. And Greg’s response inoculates the movie against seeming wholly naive or cloying. As so often, Hollywood lets us have things, emotionally speaking, both ways.

This response is accomplished through one of the most powerful weapons in the filmmaker’s arsenal. A director can disarm our emotions through a single reaction shot.

Recoil and reaction

The same sort of dynamic is at work in a less lightweight scene. Everybody remembers the moment in Jaws when Sheriff Brody, scooping chum over the side of the Orca, is taken unawares by the arrival of Bruce the shark, bursting out from the background.

But Spielberg, who understands audience response, follows this nifty shot with a topper. In a reverse-angle framing, Brody’s head snaps into the shot with the abruptness of Wile E. Coyote reacting to the Road Runner.

The sudden thrust and halt of Brody’s head sells his stunned facial expression. Our shock at Bruce’s entrance is joined by our uncontrollable urge to giggle at Brody’s cartoonish trajectory and the sheer stupefaction on his face—not fear yet, but rather a recognition of the sheer enormity of the adversary. From here on, his refrain, “We’re gonna need a bigger boat,” will remind us that unlike his shipmates, he has been very nearly head to head with the Great White.

The reaction shot seems like a simple technique. Doesn’t it just spell out or repeat what’s happening? Sometimes, but not always. As we’ve just noticed, it can let the director layer the effect of a scene. Once an action has gained a particular emotional coloring, the reaction shot can add a different tint. The romantic exhilaration of the song in Music and Lyrics is heightened by Greg’s bad-natured gaping. Bruce’s fearsome movement forward is balanced by Brody’s recoil and his comically fixed stare into space.

And sometimes the layering and balancing can take place within the reaction itself. In John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow, Mark Lee enters a restaurant and pretends to be playfully feeling up a woman in the corridor. But he’s actually planning to kill a gangland leader, who’s partying in a room off right. First shot: Mark looks winsomely off after the retreating woman. Cut to the leader celebrating.

We might expect that the return to Mark will show his fake expression fade into a sincere one. Instead, Woo simply shows a new expression on Mark’s face as he listens to the party offscreen right.

Eisenstein admired Asian theatre for its “acting without transitions”; here the brief shot of the gangster eliminates the emotional transition taking place on Chow Yun-fat’s face. Mark’s determination is all the more forceful for being so abruptly presented, as if a mask has simply fallen away.

Mirrors like big faces

Prototypically, the reaction shot shows a face expressing emotion. The technique trades on our ability to grasp expressions, often very quickly. We’ve perfected this skill since birth, and there’s evidence that newborns are pre-wired to detect and respond to certain expressions, especially from mom. Exposure to actual expressions in their daily lives allows children to refine and tune this proclivity. So one part of the reaction-shot technique is a very well-practiced skill that cinema has exploited.

Some recent findings in neuroscience suggest that reactions portrayed onscreen can arouse us deeply. Back in 1995, researchers observed that one sort of nerve cell was activated in a macaque monkey’s brain when the monkey reached for a peanut. No surprise there, since that cortical area is known to be a region involved in planning and initiating bodily movements. But researchers noticed that the same cells fired when the macaque watched another monkey reach for a peanut. Soon researchers were finding clusters of these “mirror neurons” in human beings, strongly suggesting that when we see someone do something, our brain responds as if we were doing it ourselves.

Since facial expressions involve stretching and relaxing facial muscles, it’s possible that mirror neurons play a role in arousing empathy. The mere sight of someone smiling or frowning can trigger some of the same neural events as when we smile or frown ourselves. We’ve all experienced a sort of “motor mimicry” when a radiant smile makes us involuntarily smile too. In one set of experiments, neuroscientists found that people’s mirror neurons responded the same way to film shots of disgusted faces as they did to disgusting smells in real life. Reaction shots may gain their strength from not merely our ability to understand facial expressions but the power of facial expressions to trigger in us an echo of the emotion displayed. With a string of shots of smiling faces, as in the Music and Lyrics concert, our own impulse to smile would have to be put down by force of will.

Of course, characters can display their reactions onscreen without being shown in reaction shots in the modern sense. Many films of the earliest years portray the actors in a long-shot framing of the entire action. Realizing that our eyes will turn to areas of high information content like hands and faces, directors often staged and lit the action for easier pickup of the faces. You can see examples of that in this and this earlier entry.

But the reaction shot as such implies cutting, either breaking down the scene through analytical editing or building up a scene from details (so-called constructive editing). In the 1910s, directors began systematically creating a scene from separate shots. (For more on this development, go here and here.) In this approach, particularly as practiced in Hollywood, a person’s facial expression could become part of an ongoing suite of shots, each concentrating on one item of information. Thanks to cutting, the facial reaction could be underscored, sharpened, and timed for best effect. The suddenness of the cuts to reactions in Music and Lyrics and Jaws is central to their effect.

A reaction shot need not be a close-up, and it need not show only one person. One of the funniest reaction shots in cinema, I think, occurs in The Producers, when Brooks cuts from the “Springtime for Hitler” number to the audience’s frozen, slack-jawed response. This long-shot framing suggests that we should think of the reaction shot as a functional category; it’s a role that various types of shots can fulfill.

Still, the development of the close-up as a technique is tied its function of showing responses. In silent cinema the people’s faces, reacting to the flow of story action, are providing a continual measure of the characters’ states of knowledge and feeling. Entire scenes could be played out as a string of intercut reaction shots, as Kuleshov proved in theory and the Americans showed in practice. In Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, as above, the reaction shot is virtually the dominant technique. And point-of-view cutting patterns integrated the isolated close-up reaction shot with images showing what the character was seeing.

With the emergence of sound cinema, you could argue, the reaction shot was briefly demoted. In early talkies, scenes were played in wider shots, and cut-in reactions could, in the hands of inept directors, seem brusque interruptions. But fairly quickly the reaction shot returned, usually as a stressed moment in a scene built out of more distant and neutral framings. Nowadays, with directors using fewer ensemble shots and disinclined to frame actors in prolonged, balanced two-shots, the reaction shot has retained its place in popular moviemaking.

Apart from registering a character’s response, the reaction shot also offers a broader take on the action. Noël Carroll has suggested that the reaction shot can steer us toward the proper way we should construe the whole fictional world we’re witnessing.

For instance, both fantasy fictions and horror stories feature monstrous beings. But in fantasy a troll or griffin might be benevolent. In large part, the way we construe the monster will depend on how the other characters respond. If the hero or heroine looks kindly upon the creature, as in The Golden Compass or Pan’s Labyrinth, then we know we’re not supposed to be horrified. Carroll explains:

A creature like Chewbacca in the space opera Star Wars is just one of the guys, though a creature gotten up in the same wolf outfit, in a film like The Howling, would be regarded with utter revulsion by the human characters.

Reaction shots instruct us in how to respond to the fictional world as a whole.

So robust is the reaction shot that it can stand on its own, if it gets a bit of help from context. In The Third Man, Holly Martins has been trying to defend his old pal Harry Lime from accusations of crooked dealing. When Holly visits a hospital ward, however, he sees what Harry’s bogus penicillin has done to babies. But we don’t; director Carol Reed shows us only Holly’s dispirited reaction.

As Clive James puts it:

The movie’s whole moral structure pivots on that one point. Unless we are convinced that the two men are seeing horrors, there would be no justification for Holly Martins’ delivering the coup de grace to his erstwhile friend.

A chase through feral eyes

Reaction shots can modulate across a scene, as the characters’ feelings change. But I’m also impressed by the way a scene can build emotion by developing from flat, affectless reaction shots to more intense ones. A good example is the long climactic highway chase in Road Warrior.

The outlaw gang is pursuing a tanker truck they think is full of gasoline, while Max, the Feral Kid, and a few warriors ride the monster truck. The scene’s stunts, acrobatics, and vehicular mayhem are impressive, but these qualities have been replicated in a lot of movies. What gives the Road Warrior scene a special pungency are the many reaction shots of the characters mounted on the truck. For the most part we’re aligned with them both physically and emotionally, and we are allowed to share their moment-by-moment reactions to each turn of events.

Early in the sequence, when the tanker team knocks out some pursuers, we get unequivocal reactions of jubilation.

But as the marauding gang gains control of the tanker, the reactions of the team turn to glum, nervously comic dismay.

The scene’s emotional graph is traced most thoroughly in the reactions of the Feral Kid. Throughout most of the film he has two expressions—neutral and fierce. Clinging to the side of the truck, he watches the steady progress of the pursuers with mild apprehension. If he started to shriek with fear now, the scene would have nowhere to build to. I think that we’re inclined to read his expressions as signs of his characteristic stoicism.

But when Max starts to dispatch gang members with his shotgun, the Kid lets out a hoot of pleasure. At one point a thug sends an arrow into the cab. No emotional response from Max or the Kid.

Max blows the thug off the roof of the cab. The kid crows.

The Kid’s laugh licenses us to laugh too—at the businesslike crispness of Max’s response and at the sheer infectiousness of the Kid’s admiration. (Our mirror neurons are presumably working overtime.)

The next phase in the arc comes when Max orders the Kid to crawl out onto the truck hood to retrieve the shells. Now the boy’s expression becomes cautious and a little fearful.

He sprawls on the hood and grabs the shells. At that moment Wez pops up, clinging to the front grille, and we get two lunging reaction shots.

If the Feral Kid had shrieked earlier in the scene, these cuts would have less impact. The high point of the drama is matched by the fact that finally, something has happened to scare the bejesus out of this boy. Even Max has lost his cool, wrenching the wheel ferociously.

Soon, in another laugh-inducing reaction, Wez realizes that he is point man in the crash that is soon to come.

You couldn’t ask for a better example of how reaction shots can be more than a one-off tactic. In Music and Lyrics, the quick insert of Greg gave a little jab to the scene. In Road Warrior, the Feral Kid’s changing reactions add an emotional curve to the progression of the chase. Without him, the scene would lack a whole layer of feeling.

There’s much more to say about the reaction shot. We’d want as well to talk about films that withhold information about characters’ reactions—by using enigmatic or ambiguous reaction shots, or by eliminating reaction shots altogether. (Think Antonioni, Hou, Angelopoulos, Tarr, and others.) Maybe I’ll take those matters up in another entry. For now, let’s salute one of the most enjoyable and arousing dimensions of cinematic storytelling. It only seems simple.

My quotation from Noël Carroll comes from The Philosophy of Horror; or, Paradoxes of the Heart (New York: Routledge, 1990), 16.

Title wave

The very first drafts of the outline always had Cloverfield on them. . . . Cloverfield was what I always wanted to call the movie. . . . It’s a terrible title . . . if you’re trying to sell something, who the hell’s gonna go see that?. . . But it’s cool. There’s a reason. I could state the reason, but it’s very clear it is meant to be obtuse. I believe that the film answers why it is called Cloverfield, I believe that it’s in the film, I believe that you can make that argument. It says exactly what I want it to say. But it’s very clear that we don’t want to explain it.

Screenwriter Drew Goddard, at Creative Screenwriting podcast

DB here:

Don’t think about a movie title too long. Even a familiar one can turn strange before your eyes.

This was brought home to me long ago when I showed Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan in a course. Before the film started, a student asked me, “Who is it?” I didn’t understand. “I mean, who is her fan?” It never occurred to me to take the title this way, but actually in the movie Lady W does attract a big fan.

Titles can be explicit, but they’re often metaphorical, associative, and oblique. Sometimes they’re downright obscure. But as Drew Goddard says, they can be cool.

Don’t Worry, We’ll Think of a Title (1966)

The least provocative titles are based on the protagonist’s name: Brubaker, Anthony Adverse, Erin Brockovich, Norma Rae, Speed Racer. One step removed is the title that describes the protagonist’s job or role: Gladiator, Hitman, The Cable Guy, Bob le flambeur, perhaps also The Godfather. Then there are the titles, like The Last Action Hero or Prince of Players or Little Caesar, that characterize the protagonist more figuratively.

If the movie has a pair of protagonists, the title can reflect that, as in David and Bathsheba, Pete’n’Tilly, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. When the title elevates a secondary figure, as in Melvin and Howard or Harry and Tonto, it has the effect of making us consider the relationship between the two as central to the action. When there are several main characters, we can get a title characterizing the group, not just Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice but The Professionals and The Breakfast Club.

Things get a little more curious when the title focuses on a character other than the protagonist(s). Rebecca identifies a dead character, but her aura haunts the (unnamed) heroine. Both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much refer, at least literally, to a minor figure. Why is The Wizard of Oz not called Dorothy Goes to Oz? Why does Mizoguchi’s great Sansho the Bailiff take its title from the name of the villain? It’s not as if Mizoguchi was trying to do an Ian Fleming (Dr. No, Goldfinger).

Perhaps Wizard and Sansho bear their titles because they’re adapted from literary sources that had those titles. But that just pushes the problem back a step: Why do the originals have these titles? And in asking why, I’m not asking for information about what went on in an author’s mind or a story conference. The why question here is about purpose and function. What does the title do in relation to the film’s plot or theme?

For instance, you can argue that the title of The Wizard of Oz works to highlight the seductive world of Oz, so different from Kansas, with the Wizard himself being a figure with one foot in fantasy and one in reality (since the Wizard is actually a prairie mountebank). Similarly, I’m inclined to say that Sansho the Bailiff’s title reminds us of the socially sanctioned cruelty at its center. Zushio and Anju, the fugitive brother and sister, may each escape in a different way, but Sansho’s world remains; it is our world.

Some titles are simply place names, like Casablanca, Macao, Philadelphia, or New York, New York. Others specify dates: 1860, 1900, 1941, 1984. In both strategies, the title often evokes symbolic associations or parallels with the here and now.

The title can refer to the core situation, as with Back to School or Being John Malkovich, or to a key scene, as in Sophie’s Choice and Gunfight at the OK Corral. This can get abstract and metaphorical. Housekeeping features a very offbeat approach to housekeeping. The Birth of a Nation characterizes America reborn after the Civil War. Being There describes more or less all that the cipher-like hero does. The title can even predict the action, as in The Great Escape, A Man Escaped, and Killing of a Chinese Bookie. In these instances we have anomalous suspense: Why and how will an announced action be carried out?

Reaching for the Moon (1917/ 1930/ 1933)

More rarely, the title can refer to the film’s central formal device. Through Different Eyes and Vantage Point announce that they will play with subjective point of view. The Blair Witch Project justifies its title by posing as a dossier of found student footage. The Prestige warns us that a magic trick’s surprise payoff might well be matched by one at the end of this movie. Kristin and I have long assumed that the title of Tati’s Play Time refers not only to the anarchic relaxation unleashed in the Royal Garden restaurant but also to the movie’s own perceptual strategy of making us see amusement in banal incidents.

Hitchcock, the tireless formalist, provided titles that give away his game. Rear Window announces a stationary viewpoint and a limited field of action. More fancifully, you could take Rope as announcing the film’s sinuous long takes. Family Plot is nicely equivocal, referring at once to a communal grave, a conspiracy among kin, and of course the movie’s own mysterious plot of knotty kin relations.

Then there are the generic characterizing titles, usually single-word titles like Notorious or Spellbound or Pushover or Identity or Slacker or Speed or even, probably most generic of all, Conflict (borne by at least five films, from 1916 to 1955). Here again, though, we can find puzzles.

We know why Homicidal is called Homicidal, but what purpose is served by calling a movie Psycho? Again, the source book provides the title, but Robert Bloch’s novel is narrated in the first person and the title gives us a big clue about the sort of mind we’re in. Hitchcock’s film presents the story more objectively, and it begins with Marion Crane’s theft. Those critics who see the film as blurring the boundaries between sanity and insanity would say that Marion, who impulsively commits a crime, and Norman are points on a continuum. People we take to be normal have irrational impulses, a point reinforced by Norman’s line, “We all go a little mad sometimes. Haven’t you?” After their conversation about private traps, Marion seems to recognize herself in his question.

Same old song (1997)

Many titles are citations or quotations, and they usually highlight a thematic element. Both Yankee Doodle Dandy and Born on the Fourth of July are drawn from the same song: both offer portraits of patriotism, but in very different keys. Pennies from Heaven is highly, perhaps heavily, ironic, something you can’t say about Meet Me in St. Louis.

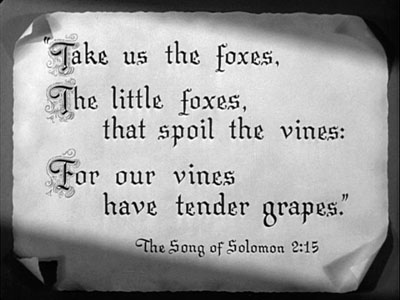

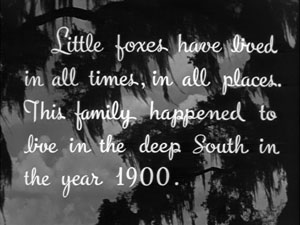

Not all citations are as transparent as these. The Little Foxes explains its title in a prologue, seen above. The Bible verse is then linked to the story we’ll see.

We’re ready to understand the family as creating a milieu that could easily corrupt the tender vine, Xan.

A catch phrase can work too, such as The Sweet Hereafter or It Takes a Thief or It’s a Wonderful Life. You Can’t Take It With You emphasizes pursuing fun rather than riches. Phffft suggests that a couple has split, but how would you explain that outside the U. S.? (The French title is, perhaps surprisingly, Phffft.)

Some catchphrase titles suggest the sort of multiple meanings we saw in Family Plot and Play Time. All That Jazz packs a lot into three words: most basically, a flurry of trivial stuff (pushing our hero into overdrive), but also music and the heights of emotion (being jazzed). You Only Live Once at first suggests seizing the moment, but by the end of the film you begin to think it implies: “Who could bear to live twice?” I especially like The Best Years of Our Lives, which also changes its significance across the film. The bulk of the movie asks: The returning servicemen have given their prime years for us, but how do we reward them? By the end of the movie, the title seems to be suggesting that their best years, of healing and self-understanding and integration into families, lie ahead of them.

I’ve known students, especially from outside the U. S., to have trouble with His Girl Friday. It’s a two-tiered reference. First is Robinson Crusoe’s “man Friday,” his aboriginal servant. But in American slang, a girl Friday is the boss’s closest female assistant, an all-around tough worker and troubleshooter. That’s what Hildy is to Walter Burns, until she decides to marry Bruce and move to Albany. She reverts to her girl Friday role in the course of the film, as the title has predicted she would.

We don’t always know when a quotation is at work. I have always found Some Came Running obscure. The phrase isn’t used in the film, or in the text of the James Jones source novel. But the novel’s epigraph takes a passage from Mark 10: 17:

And when he was gone forth into the way, there came one running, and kneeled to him, and asked him, Good Master, what shall I do that I may inherit eternal life?

This is the passage where Jesus asks the rich man to give all that he has to the poor, apparently as unlikely an event then as now. The problem is that in the Biblical passage, only one came running. The reader has to imagine several characters in the novel as “running” to ask how they will get into heaven. But the citation seems to me a mismatch, since the characters of novel and film aren’t all rich. In any case, without the epigraph tacked to the movie, its significance gets lost. This doesn’t stop me from liking the title, though.

One of my favorite instances of the obscure catchphrase-title is Ozu’s I Was Born, But . . . To decipher it you have to know that during the Depression, Japanese college graduates often couldn’t find work, and the sentence “I graduated, but . . . ,” trailing off, suggesting “. . . I’m unemployed,” was a topical one at the time. Ozu in fact made a film with that title. But then he decided to have fun with it, making a college comedy called I Flunked, But . . . Then came an even sillier extension: When he makes a film about boys, it becomes I Was Born, But . . . [I still have problems…]. Our parallel, I suppose, is the move from Honey, I Shrunk the Kids to Honey, I Blew Up the Kid.

Which reminds me: Titles have a strange habit of speaking for the character. We have I Was a Teenage Werewolf, I Dood It, I Love Melvin, Me and the Colonel, My Favorite Brunette, My Cousin Vinny, Blackmail Is My Life, and so on. This convention points up the difference between literature and film. A book with one of these titles would lead us to expect first-person narration, and it would be strange if it didn’t. A movie with such a title might provide voice-over commentary from the protagonist, as How Green Was My Valley and I Walked with a Zombie do, but more likely it won’t.

For Your Eyes Only (1981)

Many titles seem enigmatic when you first hear them. They create curiosity and build up an urge to check out the film. In most cases, the mystery gets cleared up in the course of the movie. Erik Gunneson’s Milk Punch does this through a bit of action, but more commonly the title is clarified in a line of dialogue or a motif. You have to wait for the very end of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? or Rio Bravo to get a reference to the title. A good embedded title shifts its meanings, as Best Years does. One scene of Silence of the Lambs explains the title’s relevance to Clarice’s character and shows what drives her to pursue Buffalo Bill. By the end of the film it points toward a moment when her inner pain will start to fade. And the title may reverberate beyond that moment, pointing to larger themes of injured innocence in a world of slaughter.

Sometimes the title is more oblique. Take North by Northwest. Many critics believe that it refers to Hamlet’s confession that “I am but mad North-northwest: When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.” Roger Thornhill, caught off balance by the espionage game he’s plunged into, could be said to have lost his bearings. But I’ve always thought that the compass-point title logo and the cross-hatched latitude/ longitude array that launch the movie prepare us for travel, in a roughly westerly, then northwesterly direction (New York-Chicago-South Dakota). And when Roger is sent from Chicago to Rapid City, he travels by airliner: He flies north, by Northwest. A Hitchcock joke?

We occasionally encounter a title that isn’t explained in the course of the action, so we are invited to ponder its implications. 8 ½ is a famous example; insiders know Fellini treated it as an opus number (seven features + two shorts + this new feature = 8 ½). American Graffiti can refer to the transitory events of the single night the film shows—the kids have scrawled their dramas on the town in one long summer blast. But I think you can also read the title as referring to the pop tunes that engulf and comment on the action. Americans write their graffiti on the airwaves.

In recent times Hong Kong films have tried to make their English-language titles more comprehensible, but in the golden years there were some delirious ones. We had Banana Cop, Wheels on Meals, Why Wild Girls, Gun Is Law, Tiger on Beat, Devil Fetus, Burning Sensation, Boys?, Kung-Fu vs. Acrobatic, Evil Black Magic, Ghost Punting, Takes Two to Mingle, Vampire’s Breakfast. . . Even Chungking Express and Ashes of Time aren’t straightforward. A real problem in studying Hong Kong films seriously is to explain to people that a movie called Police Story or Naked Killer can be pretty interesting. And if the titles don’t perturb them, the subtitles will.

But most of the Hong Kong titles are inadvertently puzzling, sort of accidental surrealism. Of course Surrealist filmmakers have given us many willfully meaningless titles, such as Emak Bakia and The Andalusian Dog. Arguably Brazil and even A Hard Day’s Night are in this vein (although I think that both of these can be explained in roundabout ways).

Today’s American films seem drawn to recherché titles. I heard Jonathan Caouette remark that he chose the title Tarnation for reasons he couldn’t specify; it just seemed to fit. One catchphrase, “the elephant in the room,” has founded two movies, but in such an abbreviated form—Elephant—that you might not recognize the link. I never thought I’d find synecdoche on a movie credit, since few Americans know how to pronounce it, let alone know what it means. But trust Charlie Kaufman to give it a try. (He also inadvertently stole a pun I’ve been using in film theory courses since the seventies.) But at least I think I get the title’s point, given the protagonist’s obsession to build a miniature city. Other titles are flat-out baffling.

Take Reservoir Dogs. Tarantino says “it’s more of a mood title, it just sums up the movie, don’t ask me why.” (1) I like the title. I just don’t understand why it works so well. Do certain dogs guard reservoirs, as some guard junkyards? Are these guys as vicious as dogs, as dirty as dogs, or doggy in the sense of losers, or what? In other words, why does it seem more fitting than, say, Sump-Pump Ferrets?

Despite the logo showing faces spilling out of a blossom, Magnolia doesn’t explain its title unless you dig around outside the film. During the rain of frogs, the traffic collisions take place on Magnolia Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley. So in a way, Magnolia is one point of convergence for several of the story lines that crisscross the plot. But that’s pretty thin motivation.

What about Syriana? Before I went to the film, I had heard that the title referred to an imaginary, prototypical Middle Eastern territory used in Pentagon war games and computer simulations. But Stephen Gaghan, in another Creative Screenwriting podcast, supplies details:

It was a real term. I heard it for real in a very conservative think-tank, where they said, “We’re going to redraw the map in the Middle East, we’re going to make a new country out of Syria, Iraq, and Iran—the borders of ancient Persia, less Pakistan. We’re going to call it Syriana.” I’m like, “Excuse me? Would you repeat that?” So I shot it, I had William Hurt explaining it. But I didn’t think it helped at the end of the day. We’re not going to make a new country in the Middle East right now.

As he saw the collapse of America’s invasion of Iraq, Gaghan came to believe that explaining the title would date the movie.

I wanted to go for a title that couldn’t be pegged to right now. You notice there’s no reference to Iraq in the movie, there’s just the most passing reference to 9/11, which was an improv thing we did, and there’s no Israel. I wanted the more permanent sense of what it is inside of men, particularly men in the west, that makes them believe that they can remake any region to suit their own purposes. . . . I wanted it to be specific to the film, not to the time. So that if you think about the tone of the film, when you think about what happened in the movie, it would only be Syriana, and Syriana could not skid into some other reference point.

Then there’s Cloverfield, which I’ve discussed earlier this year. Part of the movie’s mystique is that nobody can agree on what the title refers to. The creature? Central Park, where the video camera is found? An exit on California Interstate 10, near where producer J. J. Abrams has his office? On this last option, screenwriter Drew Goddard says no way:

If we would do that, we would be dicks. We would be assholes.

I don’t want to get into the labyrinthine question of the relations of Cloverfield to Lost and to the film’s viral marketing campaign online. What interests me is the fact that part of the fun around, if not exactly in, the film is playing with all these possibilities . . . and waiting to see if a sequel will explain further. Perhaps a teasing title can help get people into theatres for a followup movie.

Finally, Primer. Not only do I not understand the significance of the title; I don’t know how to pronounce it.

I Love a Mystery (1945)

Why have we seen such a rise in cryptic titles in recent years? Several factors seem important. A puzzling title lifts your film above the clutter and creates buzz as people wonder what this movie could be about. This buzz factor is multiplied by the Internet. The title can be researched through Google and discussed endlessly in chatrooms. Filmmakers know that we can revisit a film on video whenever we want, so the movie can be rescanned by eager eyes searching for clues to the title’s meaning. Mystery titles summon up the geek in us.

Which means that the current wave of peculiar titles probably owes a lot to Tarantino. In the interview I already cited, Tarantino stressed that that title of Reservoir Dogs let the audience play with the possibilities.

The main reason that I don’t go on record is because I really believe in what the audience brings. . . . People come up to me and tell me what they think it means and I am constantly astounded by their creativity and ingenuity. As far as I’m concerned, what they come up with is right, they’re 100 percent right. (2)

But then, as Jonathan Walley pointed out to me, cool opacity isn’t confined to movie titles.

Band names have always been evocative: The Rolling Stones weren’t literally rolling stones, The Pixies not literally pixies. But what many of them evoke now strikes me as much more obscure and, to quote Grandpa Simpson, “weird and scary”: System of a Down, Teeth of Lions Rule the Divine, One Day as a Lion, My Morning Jacket, etc. Many of these are alternative bands, and many of the films with these obscure titles are alt/indie films, or at least films with those pretensions, so there’s a parallel there, I’d say. The willful obscurity of title, of band or film, evokes an ironic, think-outside-the-box, you’re-not-meant-to-get-it indie attitude that appeals to the intended audience.

That is, obtuse titles for an acute public.

For comments, suggestions, and memory-jogging, thanks to the Badger Filmies: Susan Antani, Colin Burnett, Andrea Comiskey, Sydney Duncan, Stew Fyfe, Jason Gendler, Doug Gomery, Jonah Horwitz, Tristan Mentz, Jason Mittell, Tim Palmer, John Powers, Brad Schauer, Chris Sieving, and Jonathan Walley.

(1) Quoted in “Reservoir Dogs Press Conference,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerald Peary (Oxford: University of Mississippi Press, 1998), 38.

(2) Some writers have hazarded that the title derives from Tarantino’s awkward pronunciation of Au revoir les enfants, coupled with Straw Dogs, but as far as I can tell, this relies on a second-hand source–ie, a former girlfriend–and Tarantino hasn’t confirmed it.

Is there a blog in this class? 2008

Kristin here—

One year ago today, I wrote the first “Is There a Blog in This Class?” entry. The idea was to point Film Art: An Introduction users toward past entries that might prove useful in relation to various topics in the textbook. The beginning of the autumn semester seemed a good time to survey what has been posted here. We plan to make such surveys an annual feature of the blog. [For the 2009 entry, go here.] After all, there are over 200 items by now, and that number increases by about one per week. We also use the “Film Art: The Book” tag for entries that we think might be pedagogically useful, so you can always check there for updates.

From its first appearance in 1979, Film Art has offered a large and broad selection of examples illustrated by frame enlargements. Space considerations, however, always limit us to a few images from all but our most important examples. One enormous advantage of the blog is that we can use as many illustrations as we need. Some of the entries listed below can be useful as supplementary examples that go into more precise detail than we can in the textbook.

Some general entries

DVD supplements can be very useful for teaching, but many of them are lightweight fare, with actors and major crew members talking about how wonderful their colleagues are. Film Art suggests some more substantive supplements. More recent recommendations appear in “Beyond praise: DVD supplements that really tell you something.”

These days students are likely to encounter filmmakers talking about their own work, whether on talk shows, in DVD supplements, or in scholarly collections of interviews. In studying films, we need to examine their statements, which sometimes can be misleading. David ponders the question, “Do filmmakers deserve the last word?”

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

If you have aspiring filmmakers in your class, you might want to direct them to David’s “The magic number 30, give or take 4,” on the age at which most directors get started.

Chapter 2 The Significance of Film Form

During the spring of 2008, there was a lot of talk concerning the supposed decline of film criticism. In response, “In critical condition” elaborates on the four activities laid out in Chapter 2: Description, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation.

Chapter 3 Narrative as a Formal System

“A behemoth from the Dead Zone,” on the monster movie Cloverfield, discusses the concept of restricted narration in detail, touching on other Hollywood examples as well.

Virtually all the films used in Film Art are good examples of whatever technique or formal property we’re discussing. For Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, we pick apart the problems with motivation, progression, and character. We end with some comments on Steven Spielberg’s directorial style.

Two essays on David’s website deal with narrative issues. “The Hook: Scene Transitions in Classical Cinema” examines how classical Hollywood films use small-scale patterns to guide the spectator from one scene to the next. “Anatomy of the Action Film” analyzes the plot structure in Mission: Impossible: III using a number of concepts discussed in Film Art.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In “Hands (and faces) across the table,” analyses of three long takes from films made decades apart—Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007), Akira Kurosawa’s The Most Beautiful (1944), and Cecil B. De Mille’s Kindling (1915)—demonstrate the use of staging to subtly direct the viewer’s attention within the frame. This entry could be equally useful in exploring the long take in Chapter 5.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

Aspect ratios may seem a narrow, esoteric subject—especially to students! But “Godard comes in many shapes and sizes” uses many pretty pictures to demonstrate just how important framings are and how they can be distorted in DVDs. Students may be less resistant to letter-boxing after reading this.

Our discussion of 3D technology in Beowulf, “Bwana Beowulf,” also considers film style and how filmmakers so far have failed to find new ways of adjusting classical Hollywood style to 3D. People tend to have strong feelings one way or the other on the introduction of 3D, so this issue would probably generate a lively discussion.

The “Sleeves” entry compares framing techniques in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes and Kenji Mizoguchi’s A Woman of Rumor (an analysis which could be equally useful in discussing editing).

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

While at the Hong Kong Film Festival in April, 2008, David interviewed Johnny To’s editor, Tina Baz, on dealing with the complexities of shifting point-of-view in Mad Detective. Unfortunately at this point the film hasn’t been released in the U.S., either theatrically or on DVD; it is, however, available in the U.K. The interview contains massive spoilers that students shouldn’t encounter before they’ve seen the film. If Mad Detective does become available, however, it would be a challenging film to show in a unit on editing. If you’re teaching an upper-level analysis course or an introductory one to film majors, this one will get them talking. It also provides vivid examples of rapid shifts in point of view.

In “Some cuts I have known and loved,” David analyzes brief segments from five films, each centering on a particularly ingenious, striking, or flagrant cut. These are not the familiar examples usually summoned to demonstrate editing.

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

My “What does a Water Horse sound like?” covers a session of final sound mixing for Walden Films’ The Water Horse, with flashbacks to watching sound sessions for The Return of the King. David got another insight into the complexities of sound mixing in an interview with Martin Chappell, sound editor of several Johnny To films and Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide. He wrote it up as “The boy in the Black Hole.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

In “Your trash, my treasure,” David reflects on the children’s action genre as revived by the National Treasure films.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

“Manhattan: Symphony of a great city” analyses Amos Poe’s epic, mesmeric Empire II, a structural film based on a complex rendering of imagery recorded from a single window. The gorgeous frames will make both you and your students (at least the curious, perceptive ones among them) want to see the film. At three hours, it’s difficult to squeeze into a class screening, but even a generous excerpt would convey something of its fascination.

“Lines of sight and light” describes some recent experimental films, including Ken Jacobs’ Capitalism: Child Labor (2006).

In “Tracking Aardman creatures,” we presented a brief history and chronology of the great Bristol-based animation firm, responsible for Creature Comforts and the Wallace and Gromit series. If you’re showing an Aardman film in class, this will give you plenty of information on the company and on DVD availability as of January, 2008.

If you’re showing your students Warner Bros. cartoons, “Pausing and chortling: A tribute to Bob Clampett” might be useful. It gives some additional information about animation techniques and incidentally points to a teaching technique you might want to use in class.

Pixar consistently creates some of the best films (not just animated films, but films) coming out of Hollywood. It’s good news that the company is increasing its rate of release. By next spring, WALL-E, Bolt, and Up will have appeared in less than a twelve-month period. We got a fascinating glimpse behind the scenes when Bill Kinder, Director of Editorial and Post-Production, visited Madison. Some of what he said is summarized in “A glimpse into the Pixar kitchen.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Critical Analyses

Few of our entries offer in-depth analyses of single films, but “Cavalcanti + Ealing = a little-known gem” examines the narrative of Went the Day Well? and puts it into historical context. “Cronenberg’s Violent Reversals” compares the narrative structures of A History of Violence and Eastern Promises, while “Three Nights of a Dreamer” goes shot by shot through a sequence from In the City of Sylvia.

Chapter 12 Film Art and Film History

Film Art’s final chapter includes a section “The Development of the Classical Hollywood Cinema (1908-1927),” which outlines the early formulation of continuity editing. In “Happy birthday, classical cinema!,” posted December 28, 2007, we celebrating the 90th anniversary of the crucial year, 1917, when classical editing patterns crystallized into a system that has endured, with variations, ever since. We discuss some of the subtleties of the continuity guidelines of the time, with plenty of examples.

A related entry, “Rio Jim, in discrete fragments,” examines shifts in technique during the development of continuity editing, concentrating on several William S. Hart westerns of the mid-1910s. Another entry, “Lucky ‘13,” discusses the transitional year 1913 through two masterpieces that represent quite different styles.

“All singing! All dancing! All teaching!” is aimed primarily at teachers using Film History: An Introduction, who would be likely to devote a lecture and screening to the subject. Still, Film Art users might find it useful, either in relation to Chapter 9 or for the brief section on the coming of sound in Chapter 12. It assesses several documentaries on the coming of sound that had recently come out on DVD. Even for those who don’t want to show them in class, they yield considerable information. (One of the DVDs also deals with color technology up to the introduction of three-strip Technicolor in the 1930s.)

“Superheroes for sale” deals with recent trends in the American film industry.

Other entries

Although most of our entries could be read by an undergraduate, we don’t make a point of writing them for students. “Observations on Film Art and film art” has a wide readership, including other cinephiles, journalists, industry people, bloggers, filmmakers, and scholars in the other arts. A few of our entries go beyond the level of an introductory class. If you teach graduate students or have bright and enthusiastic undergraduates looking to learn more, you might, for example, steer them to this item: “Minding movies,” a brief summary of cognitive film theory, with lots of links for those who want to go further in this direction.

When we go to film festivals, we post reports on the movies we see, the old friends we re-connect with, and the new ones we meet. On a regular basis, we visit the Hong Kong, Vancouver, and Wisconsin festivals, as well as Roger Ebert’s “Ebertfest.” These entries are chatty and sometimes specific to films that students may never get a chance to see. They would be difficult to link up with Film Art. Still, they give a sense of one major aspect of film culture and show part what their textbook authors do when they’re not preparing new editions. We haven’t listed those entries here, but you can find them by clicking here or on the Festivals category on the blog. If you’re interested in a particular film or filmmaker, try a search. Perhaps we’ve said something on the subject.

When we launched “Observations on Film Art and film art,” we tended to post every few days. This year we have tried to settle into a steady, once-a-week rhythm, with new entries typically going online between Thursday and Saturday. For those teachers who might want to assign their students to read the blog regularly, we hope this schedule makes that easier.