Archive for October 2008

It was a dark and stormy campaign

How do you get people to believe that if you can’t get the press to make an honest assessment of it? You tell a story. “When it came down to a choice between my very life and my country, I chose my country.” That’s why the story’s important. Just as Obama’s story is important to him. I don’t gainsay it. You know, tell your story! —John McCain staff member and co-author Mark Salter

There was a mismatch between the way he was behaving and the narrative the press had bought into. It made reporters wonder, “Have we been had?”–Professor Marion Just, Wellesley, on John McCain

This political bullshit about narratives.–Peggy Noonan, Republican columnist

I’m David Bordwell and I approved this message.

A long time ago a student complained to me that we film academics were foisting upon them words that no professional filmmakers used. The student’s example was “genre.” Today of course filmmakers use the term all the time. Sometimes you hear “classical filmmaking,” and Variety tells us that Henry Jenkins’ label “transmedia” is starting to break through:

Famed s/f writer Larry Niven is working with “transmedia” (today’s new buzzword) production company Alchemic Productions to create a new game property called “Free Fall.”

More broadly, the terminology of Big Theory in the humanities has trickled into journalism and politics. For some time now “deconstruction” has been peppering mass-market discourse. Granted, it’s not employed in the way Derrida and his acolytes would like. It seems to mean a blend of “construction” and “destruction,” which can entail “analysis” or even just “pulling something apart.”

Deconstruct Black Ink: Your children can use chromatography to deconstruct black ink and find out what color the ink really is.

Scientists Deconstruct Clownfish Chatter

U. of Kansas Looks to Deconstruct Its School of Fine Arts

This election season has shown me that even the idea of the Other, considerably divorced from its use by Jacques “The Lack” Lacan, can show up. Nicholas Kristof claims that John McCain’s efforts to suggest that Barack Obama isn’t “sufficiently Christian” are an effort to “otherize” him.

But I think the term that has gotten the most play is “narrative.”

Discovering narrative

During my days as an undergraduate in literary studies and as a grad student in film studies, between 1965 and 1973, you scarcely ever heard the word. It doesn’t appear in the index of Wellek and Warren’s Theory of Literature (3rd ed., 1956) or Wimsatt and Brooks’ Literary Criticism: A Short History (1957) or Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism (1957). Story, tale, plot, dramatic structure: these words were common, but not “narrative”.

In American academia, the term began to gain currency with Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg’s The Nature of Narrative (1966). The authors identify narrative with a broad literary tradition, embodied not only in the novel and short story but also in oral storytelling. And the definition is clearly language-based, in pointed contrast with drama.

By narrative we mean all those literary works which are distinguished by two characteristics: the presence of a story and a story-teller. A drama is a story without a story-teller; in it characters act our directly what Aristotle called an “imitation” of such action as we find in life. (4)

The Nature of Narrative was published the same year that Roland Barthes, in a special issue of the French journal Communications, published his essay “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives.” (1) His conception of narratives (récits) is far more generous than that of Scholes and Kellogg.

Narrative is first and foremost a prodigious variety of genres, themselves distributed amongst different substances—as though any material were fit to receive man’s stories. Able to be carried by articulated language, spoken or written, fixed or moving images, gestures, and the ordered mixture of all these substances, narrative is present in myth, legend, fable, tale, novella, epic, history, tragedy, drama, comedy, mime, painting (think of Carpaccio’s Saint Ursula), stained glass windows, cinema, comics, news item, conversation. (79)

Barthes’ essay, along with other Structuralist studies, initiated the academic field of “narratology,” the systematic study of storytelling as it is manifested in many media. From the 1970s to the present, this became a vast, varied, and exciting area of inquiry.

The questions are fascinating.

*What is a story? How does it differ from other things, such as a description or an abstract image? Are jokes narratives? Are dreams? Are riddles? Is the concept so broad that anything can be treated as a story?

*Why do stories engage us? What do we need to know, or do, to understand a story? What powers enable us to create stories? Are story-making and story comprehension distinctively human activities?

*Do stories rendered in language differ from those rendered in other media? Is the ability to make or follow stories dependent on our knowing language, even if the story is presented without words (as, say, a silent film)?

*How do narratives imply or suggest or symbolize broader meanings than the bare events they recount? What enables a narrative to stand for more than it seems to say?

*What patterns of narrative construction do we find in different traditions, periods, times, and places? How might they bear the traces of social and political views? How might they express varying conceptions of the world?

In retrospect, we can see that Aristotle, nineteenth-century theorists of the drama, and theorists like Walter Benjamin, Georges Polti, R. S. Crane, and Northrop Frye did reflect on the phenomenon as narratologists were beginning to conceive it. But very few thinkers had asked these particular questions, in quite the way that Barthes and other Structuralists had.

The questions may seem impossibly abstract or broad, but they get more manageable if we look at particular cases. Take film. We all assume that Hollywood movies belong to a storytelling tradition, one that some people consider formulaic. But if Hollywood movies are formulaic, they must adhere to conventions—conventions we might not find, say, in Homer’s epics or Ibsen’s dramas or Neorealist films. What are those narrative conventions? Where did they come from? How do they fit together? What might be their effects on viewers’ beliefs and experiences?

Studying the narrative conventions of various filmmaking traditions has kept Kristin and me busy for many years. We explained some rudiments of narrative theory in the first edition of Film Art (1979); I think that this was the first time an introductory textbook put the area on the film studies agenda. In the 1980s we wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema and Narration in the Fiction Film; in the 1990s Kristin wrote Storytelling in the New Hollywood; in the 2000s I wrote The Way Hollywood Tells It and Poetics of Cinema. Most recently we composed some items on this website (here and here and here).

Now, after a thirty-year pageant of academic theories and analyses, we find that the term has trickled down, so to speak, to bare-knuckle politics. It turns out that the current Presidential election in the U. S. is all about “narratives.” The candidates have them, as do the campaigns. And those narratives are served up in newspaper accounts that are also narratives. How the word gained its new status is a question for another time. For now, we have plenty of tales to occupy the narratologist.

Two quick caveats

Narrative doesn’t equal fiction. Most narratologists have followed Barthes in treating factual accounts, like newspaper stories and conversations, as narratives. Sometimes a filmmaker will say, “I make documentaries, not narratives,” but documentaries can be, and often are, narrative in form. So too are some avant-garde films, such as Meshes of the Afternoon and Tribulation 99. One of the reasons that we study narrative is that it’s a very widespread phenomenon.

This is not to say that the fact/ fiction distinction doesn’t matter. We react differently to narratives purporting to be fictional and ones claiming to be factual. And studying narrative doesn’t commit us to saying that all narratives are fictional (because they’re constructed, or because they’re selective, or whatever). History books and newspaper reports can be more or less faithful to what really happened. And sometimes fact seems more narratively coherent than fiction. If you wrote a novel about an idealistic presidential candidate born in a town called Hope, you’d be accused of heavy-handed symbolism; but tell that to Bill Clinton.

Narrative is a type of representation. What happens to you today isn’t a narrative until you tell somebody about it, or write it up in your diary, or at least sort it out as a story in your mind. A narrative, as the name implies, is a string of events that is narrated—represented in some form. In this sense, the Presidential campaign isn’t a narrative in and of itself. It becomes a narrative when people represent it: select events, omit others, perhaps invent or imagine still others, and present them in words, pictures, music, or some other medium.

This idea of presenting a chain of causally connected events, enacted by agents and unfolding in time, is what we characteristically mean by storytelling. You can find a more abstract definition of narrative in Film Art and other things Kristin and I have written, but this will suffice for now.

The plots thicken

Clearly the presidential candidates have come to believe that what seizes the public aren’t just policy views and promises. Now the campaigns want to tell stories in which the candidates are the protagonists. The life of Barack Obama, or Joe Biden, or Sarah Palin is said to be a story (usually “an American story”). According to Robert Draper’s influential recent article, John McCain’s campaign has deliberately set out a series of “narratives”: McCain endures suffering in Hanoi as a POW; he enters politics and fights for reform in government. Mark Salter, McCain’s staff member and coauthor, has the responsibility of stitching incidents of the Senator’s career into what he calls the “metanarrative” of McCain’s life—rather as George Lucas presides over the Bible of the Star Wars universe.

The campaigns’ efforts at representing narratives don’t just amount to giving us backstory about the protagonists. Things get tricky when they try to present the ongoing campaign as itself a narrative. This involves planning a smooth cascade of events, such as during the party convention, when the suspense builds toward the climax of nomination. The problem of course is that events outside the candidates’ control can force changes in the story line. During the recent financial meltdown, McCain’s campaign would have preferred to create a dialogue about national security, and Obama’s campaign was prepared to talk about the war and the squeeze on the middle class. Instead, each had to respond to swiftly changing events and rewrite the script every day.

Why is the McCain campaign flagging? Contrary to Salter’s intentions, many believe that it never found “a compelling story”—that is, a way to integrate all the events hurled at their ideal scenario. Obama’s story was simpler: he could simply point to each new catastrophe as caused by Republican rule.

Sometimes the mass media replay the narratives concocted by the campaign, but sometimes they offer counter-narratives. A Rolling Stone article sought to replace the official McCain “metanarrative” by adding incidents, characters, and causes that add up to a far more damaging story. More broadly, a common account portrays the campaigns as a study in contrasts: Obama’s enterprise ran steadily according to the well-planned strategy of pursuing votes in nearly every state, while McCain’s campaign was more tactical and reactive, taking red states for granted. And as in any good narrative, the actions are treated as reflecting the traits of the two characters. Obama is seen to be calm and measured, so his campaign runs smoothly; McCain appears splenetic and tightly wound, so his campaign is spasmodic. Character and action are believed to mesh. (More on character traits shortly.)

Once these narrative arcs are in place, they become hard to dislodge. As I write this, unnamed handlers in the McCain campaign are blaming one another and Sarah Palin, and this new string of incidents only seems to confirm the scenario of a rudderless, probably doomed, enterprise. Other observers, and historians in future years may embellish, revise, or reject the mainstream account. My point is that we’ve watched a standard story emerge as a full-bodied narrative, or rather a cluster of them—the way that a folktale or myth presents different variants of emphasis and point of view. Still, each one of the variants is a narrative—a representation of a string of events, enacted by agents and bound together through chronology and causal connections.

What’s your story?

I long ago learned to distrust my childhood and the stories that shaped it. It was only many years later, after I had sat at my father’s grave and spoken to him through Africa’s red soil, that I could circle back and evaluate these early stories for myself. Or, more accurately, it was only then that I understood that I had spent much of my life trying to rewrite these stories, plugging up holes in the narrative, accommodating unwelcome details, projecting individual choices against the blind sweep of history, all in the hope of extracting some granite slab of truth upon which my unborn children can firmly stand.

Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father, xv-xvi

Each of the two top presidential candidates has signed an autobiography that functions, in today’s story-hungry ecosystem, as a bid to control his narrative. In 1995, Obama published Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance; four years later McCain produced Faith of My Fathers: A Family Memoir. In what follows, I’ll refer to the latter as McCain’s book, though apparently coauthor Mark Salter is responsible for both a lot of the research and the actual prose of the result.

Like Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, Obama and McCain are deeply concerned with fathers and how they shape sons. Both books portray three generations of men: the author, his father, and his grandfather. The concern for the father’s role is enacted in the overall design of each narrative.

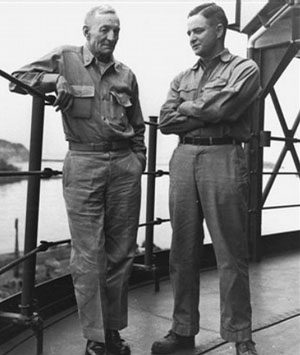

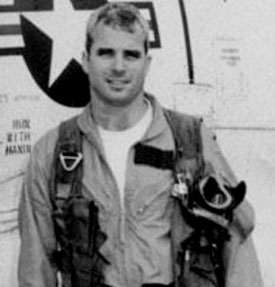

McCain’s book is more straightforwardly chronological, and it proceeds in three layers. After an emblematic moment when his father and grandfather met at the end of World War II (more on this below), the narrative starts with a brief biography of the elder, McCain senior, who served as an admiral under William Halsey during World War II. There follows a somewhat longer account of McCain junior, who also won the rank of Admiral and who commanded naval operations during the Vietnam war. Woven into these accounts are vignettes of the youngest McCain’s reactions to these two awe-inspiring warriors.

The bulk of the book presents his own life, rendered chronologically. He swiftly runs through a “misspent youth” of impulsive rebellion and reluctance to kowtow to authority. McCain expresses gratitude for the family heritage—a sense of duty and, above all, honor—that informed his life. But he did not fully understand the weight of these traditions, he tells us, until he was taken prisoner by the North Vietnamese and was held as a POW for over five years. There, under severe torture and despite the greatest resistance he could muster, he signed a false confession. It was a betrayal not only of his country, but of a family tradition.

They were the worst two weeks of my life. I couldn’t rationalize away my confession. I was ashamed. I felt faithless, and couldn’t control my despair. I shook, as if my disgrace were a fever. I kept imagining that they would release my confession to embarrass my father. All my pride was lost, and I doubted I would ever stand up to any man again. Nothing could save me. No one would ever look upon me again with anything but pity or contempt. . . . The Vietnamese had broken the prisoner they called the “Crown Prince,” and I knew they had done it to hurt the man they believed to be a king. (244-245)

The rest of the narrative tells of redemption. Months of poor medical care, mind-numbing routine, solitary confinement, and spasms of torture had made McCain vulnerable. But in living with other prisoners, McCain discovers that loyalty to country merged with loyalty to comrades and to God. Honor and duty are bound up with faith.

I was no longer the boy to whom liberty meant simply that I could do as I pleased, and who, in my vanity, used my freedom to polish my image as an I-don’t-give-a-damn nonconformist. . . . In prison, where my cherished independence was mocked and assaulted, I found my self-respect in a shared fidelity to my country. All honor comes with obligations. I and the men with whom I served had accepted ours, and we were grateful for the privilege. (255)

By the time he is released, McCain—now living with other prisoners—can help create the bonds that make them resist, and occasionally subvert, their captors’ plans. (Among other things, he enlivens their nightly meetings with long recitations of the plots of movies he has seen.) And he refuses to be released out of the sequence of his capture. At the end, on the verge of freedom, the boyish McCain reemerges, offering some insolent quips to Vietnamese officers. He returns home, not to his father—that conventional scene is oddly absent—but to a greater sense of his responsibility.

McCain has spoken of Viva Zapata! as his favorite film, but in reading the book I couldn’t escape the feeling that it traces, in a less light-hearted tenor than Ford’s film does, the way in which Ensign Pulver becomes Mr. Roberts.

The narrative arc of Dreams from My Father is far less linear in its plot. At bottom, it is a conventional autobiography, telling how a boy born in Hawaii to an American mother and a Kenyan father, wound up going to law school. Unlike McCain, who grew up knowing about the triumphant careers of his father and grandfather, Obama never really knew his father. His parents divorced when he was two, and he saw his father only once, when he was ten. His mother, and then his grandparents, were his family. The narrative is, like McCain’s, presented in three parts, but these correspond to three stages of the protagonist’s life: an early phase of childhood, high school, and college; a period of young manhood spent in Chicago, organizing community groups for social improvement; and a trip to Kenya before entering Harvard.

If McCain’s book is an adventure tale, Obama’s is a detective story. The through-line, as screenwriters might say, is Obama’s search for his identity as a African American. If McCain’s plot is driven by honor and duty, Obama’s depends on race and social responsibility. McCain steers by a fixed star, and is shamed when he goes off course. Obama is scanning the heavens for some stable pole that will give him a sense of who he is.

In Chicago, he is confronted with the poverty and fragmentation of the black community. Some failures and moderate successes in community organizing give his young life a degree of purpose. He learns from Harold Washington and various preachers, surrogate father figures, that there are larger forces working to tear apart the fragile unity citizens might achieve. The chief danger is losing hope. Attending a service by Jeremiah Wright and hearing talk of “the audacity of hope,” Obama has a conversion:

If a part of me continued to feel that this Sunday communion sometimes simplified our condition, that it could sometimes disguise or suppress the very real conflicts among us and would fulfill its promise only through action, I also felt for the first time how that spirit carried within it, nascent, incomplete, the possibility of moving beyond our narrow dreams. (294)

But still his own history feels incomplete, and he sets out to complete it by visiting his father’s tangled family in Kenya. He finds he has many brothers, sisters, aunts, and uncles. He witnesses deep divisions in a squabble over his father’s estate, and he comes to realize how family bonds can be both liberating and stifling. As he explores, he learns more about his father and, eventually, his grandfather.

McCain gives encapsulated judgments of his father and grandfather, while Obama keeps offering partial portraits, images slipping in and out of focus. His father was a noble man, much respected till his death; no, he fell into drunken lassitude; no, even in his decline he was generous and loyal to his friends. Eventually, talking with his grandmother, Obama learns of the history of his father’s family. As in a detective story, the book’s climax is a recitation of what the protagonist had never known, the hidden causes of why his mother and father divorced—and the revelation of a secret his mother and her parents had always kept from him. Like McCain, Obama finds himself, but not through living up to an external code of conduct. By an act of sympathetic imagination, Obama grasps how he continues to live, in his own register, the problems and promise embodied in a man who had abandoned him two decades earlier.

Obama’s tale is more complex than McCain’s, but each one reflects the image of the protagonist. McCain lives in a world of clear-cut demands, called the Code, and so any problem comes from failing to meet the obligations of duty. Obama’s world is hazy and uncertain; there is no Code. How should a man like him, with his heritage, find a way to live with dignity?

Telling details

The differences in the overall narrative progression get embodied in differences at the level of texture, or narration—the concrete way each story is told, moment by moment. Consider the opening of Faith of My Fathers:

I have a picture I prize of my grandfather and father, John Sidney McCain Senor and Junior, taken on the bridge of a submarine tender, the USS Proteus, in Tokyo Bay a few hours after the war had ended. They had just finished meeting privately in one of the ship’s small staterooms and were about to depart for separate destinations. They would never see each other again.

Despite the weariness that lined their faces, you can see they were relieved to be in each other’s company again. My grandfather loved his children. And my father admired my grandfather above all others. My mother, to whom my father was devoted, had once asked him if he loved his father more than he loved her. He replied simply, “Yes, I do.”

And here are the opening lines of Obama’s memoir:

A few months after my twenty-first birthday, a stranger called to give me the news. I was living in New York at the time, on Ninety-fourth between Second and First, part of that unnamed, shifting border between East Harlem and the rest of Manhattan. It was an uninviting block, treeless and barren, lined with soot-colored walk-ups that cast heavy shadows for most of the day. The apartment was small, with slanting floors and irregular heat and a buzzer downstairs that didn’t work, so that visitors had to call ahead from a pay phone at the corner gas station, where a black Doberman the size of a wolf paced through the night in vigilant patrol, its jaws clamped around an empty beer bottle.

A card-carrying narratologist could squeeze a whole article out of these two openings, but just notice how well designed each is. Both grab the reader: Why would McCain’s father and grandfather never meet again? What was “the news” headed for Obama? The short, crisp sentences of the McCain extract—few adjectives and adverbs, no description except for the lines on the men’s faces—set the pace for what we’ll get later. McCain (via Salter) tells his tale in brief paragraphs and unvarnished prose, as laconic as the talk of the seamen he admires. The two opening scenes, that of father and son meeting on the bridge of the Proteus and the moment when McCain’s father tells his wife that he loves his father more than her, might have come from a John Ford film. The climactic “Yes, I do” even enacts that legendary Ford dictum that you shouldn’t let actors talk much.

Obama’s scene is more like a sequence from a 1970s urban movie, yielding washed-out imagery packed with scruffy detail. Everything suggests “dangerous neighborhood” and “black poverty,” but at no point does Obama use any of those words. Instead we get suggestions of grime and bleakness. As in many novels, the milieu comes to life through action: the broken buzzer initiates the routine of people calling ahead. By metonymy, the adjacent gas station reminds the narrator of the almost hallucinatory Doberman trotting through the night. And instead of telling us that drunkards left their beer bottles littering the streets, this paragraph suggests this sorry milieu obliquely by having the patrol dog clenching one in its jaws.

It might be tempting to say that McCain is deliberately avoiding literary grace notes, as befits a man identified with Straight Talk, while Obama is writing in a self-consciously novelistic way, like the elitist he is. Actually, no. Both are writing in literary ways, but using different techniques of narration.

Obama is adhering to Henry James’ admonition to “Dramatize, dramatize!” He tries to make every scene come alive for the reader through small details. He’s the sort of memoirist who not only gives you twenty-year-old conversations word for word, but adds all the gestures, vocal tones, and props.

“See there,” Marcus said. “Makes you embarrassed, don’t it—just being seen with a book like this. I’m telling you, man, this stuff will poison your mind.” He looked at his watch. “Damn, I’m late for class.” He leaned over and pecked Regina on the cheek. “Talk to this brother, will you? I think he can still be saved.”

Regina smiled and shook her head as we watched Marcus stride out the door. “Marcus is in one of his teaching moods, I see.” (103)

This sort of prose is movie-adaptation ready: You can see the scene. McCain doesn’t work at this level of concrete rendition, but his narration is no less carpentered. Consider this passage:

I didn’t think, “Gee, I’m hit—what now?” I reacted automatically the moment I took the hit and saw that my wing was gone. I radioed, “I’m hit,” reached up, and pulled the ejection seat handle.

I struck part of the airplane, breaking my left arm, my right arm in three places, and my right knee, and I was briefly knocked unconscious by the force of the ejection. Witnesses said my chute had barely opened before I plunged into the shallow water of Truc Bach Lake. I landed in the middle of the lake, in the middle of the city, in the middle of the day. An escape attempt would have been challenging. (189)

Things happen quickly here. The scene is over in seven sentences—no description of what the blackout felt like, no sense of imminent death. Point of view switches with equal speed. McCain is fully aware until he’s flung out of the plane and loses consciousness. Then his narration has to resort to an objective report of what happened while he was out. (“Witnesses said…”) The statement is backed up by a quick, vernacular summary of where and when he landed. The tone then switches to understated reflection, using the flat language of the stoic man of war: Escape wouldn’t have been impossible, or fatal, merely “challenging.” The paragraph plays down the crisis of survival by tapering into ironic self-effacement.

The rule of three is one of the writer’s best friends. The last sentence of the first paragraph renders three McCain actions—radioing, reaching, and pulling—in swift succession. Injuries pile up in triple-formation too: arm, arm, knee. The third trio is casual but memorably repetitive: middle of the lake, middle of the city, middle of the day. Should McCain claim that he, like Hamlet, “uses no art at all,” a narratologist will remind him of the technique pervading this passage—and his book’s opening. In a novel, mentioning a ship called Proteus would foreshadow the changes that young John will undergo. And James Wood complains in his recent How Fiction Works that a great many “apprentice novels” begin with the narrator pondering a family photo (95-96).

Percy Lubbock’s The Craft of Fiction (1921), a classic of literary narratology, distinguishes two methods of narration. The scenic method strives to make each moment palpable through energetic description, while the panoramic one inclines toward summary and generalization. Along this (fairly rough) continuum, Dreams from My Father lies closer to the scenic pole and Faith of My Fathers is closer to the panoramic one. Both autobiographies deploy the rhetoric of fiction, and both are unavoidably artificial. And each one’s technique (subtly eloquent versus direct and plain-spoken) creates a voice that fits the man’s narrative and his public persona.

Peopling the story

Characters in a narrative are usually identified by their roles and their traits of personality. Indiana Jones is a professor and adventurer, an intellectual cowboy. He is courageous, knowledgeable in his field, risk-loving, a bit insolent, somewhat impetuous, and so on. (For more on character construction, see my third essay in Poetics of Cinema.) Given very few cues we can fill in a character, so it becomes important that people who would become characters in their own stories send out the right signals. Rewriting real life is hard.

In the presidential campaign, it isn’t hard to identify the traits that the candidates are trying to define. All want to show integrity, resolve, prudence, a willingness to sacrifice for the greater good, and so on. But each candidate has also become identified with more individual traits. Without my enumerating them, let’s try a game.

Imagine our candidates as people in a high school. (2) Which one is the assistant principal on the verge of retirement? Which one is the social studies teacher who can always be led off the lesson plan with a strategically innocent question? Which one is the earnest first-year teacher, convinced that he can reform secondary education by reaching miscreants? And which one is Miss Popularity, cruel queen of the cliques, bluffing her way through assignments?

Maybe you don’t agree with my assessment of the candidates’ traits, but you knew exactly whom I referred to in each case. That’s because at least one narrative frame has sorted the characters along these lines. It’s a little scary to see that a flesh-and-blood person can be “characterized” so stereotypically, but whatever our political protagonists are like privately or deep down inside, as characters in the narratives that they spin or others spin around them, they fit well-worn templates.

Indeed, they can strive quite consciously to do that. To claim to possess “audacity” or to call yourself a “maverick” is to conjure up a set of traits, and these have implications for how you will act. As your actions mount up, a portrait snaps into focus that is hard to eradicate. Sarah Palin, introduced as a hard-edged fighter in the mold of Hillary Clinton, has been the most obvious instance of gradual revelation. She was an outline waiting to be filled in with events, and despite the campaign’s efforts to control what those events were, damaging pieces of behavior have mounted up and campaign leaks have confirmed their dire side. Palin now stands as a provincial politician adept at small-scale patronage whose ignorance of policy, world affairs, and science is abysmal and invincible. This has not kept some people from admiring her, of course.

Palin betrays no change in personality over the course of the campaign, and neither does Biden. According to reporters who cover him, he’s the same Joe he always was, take it or leave it. For real change—not of America’s direction but of public personas—we need to look at the top of the ticket. In the course of the campaign, for example, Obama has managed to seem consistent with his core program while having “seasoned” and “matured,” thanks to the tough primary fights. (Another cluster of narratives I can’t tackle here.)

McCain has been rendered as changing too, but not in a good way. One prominent large-scale narrative has portrayed him as losing some of his independence of thought—tacking to the right on cultural matters, losing the argument about his running mate. Few speak of the old Barack Obama versus the new one, but the narrative of John McCain 2.0 has stuck. Mr. Roberts has become the captain himself—a man crumpled with vexation, the cranky officer he would have rebelled against at Annapolis. I suspect that some day a McCain biographer will construct a narrative that shows him to have become a tragic figure.

The big three ingredients

Narratives arouse emotions in us; some would say that’s their chief purpose. The emotions can be of all kinds—pity, sympathy, indignation, joy, and down the line. But are there emotions characteristic of narrative in general? The theorist Meir Sternberg (3) has suggested that a narrative as such, regardless of other emotions it can conjure up, depends on three emotional states. Simplifying a bit, we can say that stories create curiosity about past events, suspense about future events, and surprise by means of unexpected events. Whatever other emotions a narrative evokes, we need to feel at least one of these three states.

Most narratives invoke all of these, but some genres rely on more than others. Detective stories rely a lot on curiosity, as characters try to solve the crime by exposing the events that led up to what’s happening now. Likewise, psychological tales—like Obama’s search for his roots—will evoke curiosity about the origins of events or personality traits. Action-driven narratives rely heavily on suspense: Will the protagonist reach her goals, or even just survive? The Dark Knight, with all its ticking clocks and hairbreadth escapes, is driven chiefly by suspense. (For more on suspense, you can visit this entry.) Plots with “a sting in the tail,” such as in stories by O. Henry and Roald Dahl and the early films of M. Night Shyamalan, have endings that depend to an unusual degree on surprise.

We can distinguish the two Presidential campaigns’ “master narratives,” along these dimensions. In the ongoing electioneering, Obama’s campaign is now driven almost completely by suspense. He’s not asking us to find out more about what led to the war in Iraq or the economic collapse or the crumbling infrastructure; it’s assumed that we know enough backstory. Everything is about what comes next. Ask any Obama supporter the predominant emotion she or he feels, and I’ll bet it will be suspense. What will happen next? What could throw the juggernaut off course? Fingers crossed: The very image of suspense.

McCain, by contrast, is running a campaign driven by curiosity and surprise. Many of his talking points dwell on the past. Who is Barack Obama, really? What did he have to do with Ayers, Rezko, the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac executives? Why did he sit in Jeremiah Wright’s church? And so on. These questions ask us to feel curiosity in the form of suspicion about McCain’s rival. The fact that most in his audience haven’t taken up the hint has driven the campaign to try to invoke another emotion: surprise. The pick of Sarah Palin is the most obvious instance, but several others have followed: suspending the campaign, promising to buy people’s mortgages, yanking Joe the Plumber out of obscurity as an emblem of small business, even the “not ready yet” tagline of a recent ad. There may be more surprises to come, as gloomy Democrats fear (which only increases their feeling of suspense). At this point, the act of winning would be the ultimate McCain surprise.

So the campaigns may teach us something of interest about narratives: You can’t have a gripping narrative without some suspense. You can do without curiosity or surprise, but a story lacking suspense won’t keep us turning enough pages to be curious or surprised. (4) Maybe that’s why the McCain campaign never had a “compelling narrative.” It didn’t build up enough of a sense of how it would win or how, after the election, the future would be different.

Narrative plus

On 29 October, the Obama campaign ran a 30-minute television film, American Stories, about why he should be president.This infomercial is a gift to the film analyst, and there’s much more to say about it than I can articulate here. I’ll concentrate on one intriguing aspect of it.

Narrative isn’t the only way to organize a film or literary text. In Film Art, we suggest that there are other principles of organization. Using categorical form, you can survey different types of things, like baseball cards or political systems, without telling a story. You can use a rhetorical format, making an argument for a position you believe in by adducing reasons. What we call associational form can link various images, sounds, and actions through analogy, contrast, or metaphorical connection; one example would be the film Koyaanisqatsi. And very often these principles can combine in a single book, film, or tv program.

American Stories isn’t centrally about Obama’s life or his family or running mate. Instead, the campaign created a series of anecdotal narratives. In turn, these narratives were linked by associations, not by the causal connections typical of narrative. Most broadly, Obama framed these narratives and linkages within a set of policy statements, so that the narratives provided illustrative examples of a rhetorical argument.

A football mom can’t pay for her husband’s medical treatment and must ration the kids’ snacks. An elderly retiree who paid off the family house must return to work to pay for his wife’s medications. A teacher in a school for at-risk kids must take a second job and still find time for her training, while deciding whether to buy a gallon or half-gallon of milk. A loyal Ford assembly-line worker is dropped to half-time; unlike his father and grandfather, he cannot expect a full pension. “Everybody here’s got a story,” Obama remarks.

The stories serve to illustrate a checklist of Obama’s positions: rescuing the middle class by means of tax cuts, making corporations accountable for pension fulfillment, working for energy independence, reforming health care, and shifting the war on terror to Afghanistan. So far, so categorical. But these talking points aren’t linked by logical inference but by association.

Take the story of teacher Juliana Sanchez. She instantiates the ‘education’ idea. Cut to Obama saying that teachers can do only so much: Parents must take responsibility for their children’s learning. Just as Juliana is taking care of her children, Obama recalls his mother taking care of him, as a single parent. Over family photographs he tells of his mother rousing him from bed to go through his lessons before she went to work. Link to Obama giving a speech in which he declares that every child needs a world-class education. Cut to him addressing the camera, declaring that he’s seen school reform work. The political has become doubly personal, exemplified by Juliana and by Obama’s own experience.

Then: “Just as I believe that every American has a right to an affordable education, I also believe that every American has a right to affordable health care.” This segues to a statement of Obama’s medical policy, which is followed by an account of his mother’s premature death, in which he shows that he knows what it is to lose a loved one. “It felt arbitrary.”

While the local connections are driven by associations like these, the overall shape of the half-hour is—no surprise—rhetorical. Obama is adducing reasons to vote for him. His case is that Americans are facing problems to which he has solutions. He could have presented the solutions as a list, in the form of bullet points or charts. Instead, he makes the problems concrete by illustrating how they affect ordinary people, including his own family, and then presents his solution by talking to an audience.

This use of rhetorical form contrasts with the one we discuss in Film Art (Chapter 10), when we analyze The River (1937). In that film, director Pare Lorentz doesn’t highlight individuals’ experience but creates a vast, sweeping story of erosion on the Mississippi river. Correspondingly, Lorentz doesn’t give the solution to the problem as a speech; it is presented in images of people taming the river, building the dam, and settling in new communities.

Obama could have adopted Lorentz’s strategy by tracing a broad history of the last eight years of Republican government, leading up to the financial crisis as a climax of mismanagement, and then turning to his policy prescriptions. He chose, as his campaign has largely chosen, not to rehearse the mistakes and misdeeds of the past (with which many Democrats were involved as well) but to put the emphasis on current conditions and hope for the future. Instead of Lorentz’s epic sweep, which arouses a feeling of grandeur and civic pride in getting a big job done, the Obama film asks us to empathize with “Americans looking for real and lasting change that makes a difference in their lives.”

Thanks to this blend of different types of formal organization, even the abstractions of policy draw upon the powers of storytelling. Maybe this campaign really is all about narratives. If so, maybe narratology can illuminate public discourse in useful ways.

Just don’t call this blog entry a deconstruction.

(1) Roland Barthes, “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives,” in Image Music Text, ed. and trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977). Barthes’ essay originally appeared in Communications 8 (1966), devoted to semiological research into narrative. Assembling a veritable who’s who of Structuralism, the issue included essays by Greimas, Bremond, Eco, Todorov, and Genette, as well as Christian Metz’s essay on the “Grand Syntagmatic” of narrative film.

(2) People say that Hollywood is high school with money, and that Washington is Hollywood for ugly people. So Washington must be high school, money, and ugly people? Obama and Palin seem to disprove the last condition.

(3) Sternberg laid out these principles in Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), one of the finest studies of narrative theory I know. He elaborated the ideas in two articles under the title “Telling in Time.” See Poetics Today 11, 4 (Winter 1990), 901-948, and 13, 3 (Fall 1992), 463-541.

(4) Of course there is suspense on the McCain side too, but more and more it consists of the question: How bad will the damage be? Although the Obama campaign hasn’t exploited curiosity about McCain’s campaign narrative, the press has done so by slowly creating a backstory about Palin’s record and the way she was selected.

Categorical coherence: A closer look at character subjectivity

Subjective

[NOTE: There are some spoilers here, though I’ve tried to avoid giving away the ends of the films I mention. Teachers who show clips in class would probably want to do the same. Some of the films mentioned here would be good choices to show in their entirety to classes when they study Chapter 3 of Film Art.]

Kristin here—

We have had occasion to mention the Filmies list-serve of the Department of Communication Arts’ Film Studies area here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Current and past students and faculty, sometimes known as the “Badger squad,” share news, links, and requests for information. Once in a while a topic is raised for discussion. These exchanges are usually fascinating, and when we have felt that they might be of interest to a general audience, we have used them as the basis for blog entries. (See here and here.)

Another occasion arose recently, one which relates to the teaching of Film Art: An Introduction. Matthew Bernstein, of Emory University, queried the group about suggestions for teaching a section of the third chapters, “Narrative as a Formal System.” He found that the section, “Depth of Story Information,” gives some students trouble. They can’t grasp the distinction we make between perceptual and mental subjectivity.

Our definitions of the terms go like this. Perceptual subjectivity is when we get “access to what characters see and hear.” Examples are point-of-view shots and soft noises suggesting that the source is distant from the character’s ear. In contrast, “We might hear an internal voice reporting the character’s thoughts, or we might see the character’s inner images, representing memory, fantasy, dreams, or hallucinations. This can be termed mental subjectivity.”

We then go on to give a few examples. The Big Sleep has little perceptual subjectivity, while The Birth of a Nation contains numerous POV shots. We see the heroine’s memories in Hiroshima mon amour and the hero’s fantasies in 8 ½. Filmmakers can use such devices in complex ways, as when in Sansho the Bailiff, the mother’s memory ends not by returning to her in the present, but to her son, apparently thinking of the same things at the same time.

Yeah, but what about …?

Filmmakers don’t always use these categories in straightforward ways. They may oscillate between perceptual and mental representations and events. Films may present narrative events that make the distinction between characters’ perceptions and their mental events ambiguous. That’s why in introducing the concepts, we stress that “Just as there is a spectrum between restricted and unrestricted narration, there is a continuum between objectivity and subjectivity.

Easy to say, but not necessarily so easy to grasp for a student who’s trying to understand these categories. They need to start with simple examples to familiarize themselves with the basic distinction before going on to what the likes of Resnais, Fellini, and Mizoguchi can throw at them. But some students immediately proffering exceptions. As Charlie Keil, of the University of Toronto, put it in his post on the subject, “I hardly need add that students, even the least analytically astute, border on the brilliant when it comes to suggesting examples that provide challenges to categorical coherence.”

Looking over the one and a half pages of the textbook that we devoted to depth of narration, you might find it fairly straightforward. Once you start looking for ways to teach the concepts without bogging down in too many nuances and subcategories, though, the passage does seem challenging. What follows is a suggestion about how someone might go about explaining and utilizing examples. It also points up some ways we might revise this passage of the book for its next edition.

What it’s not

One obstacle that Matthew has found is that students are used to thinking of “subjective” as meaning something like “biased,” as in “here’s my subjective opinion on that.” It might be useful to point out that this is only one meaning of the word. The dictionary definition that comes closest to the way we use it in Film Art is this: “relating to properties or specific conditions of the mind as distinguished from general or universal experience.” For film, we specify that “subjective” means either sharing the characters’ eyes and ears (properties) or getting right inside his or her mind (conditions).

Another misconception comes when students assume that the facial expressions, vocal tones, and gestures used by actors are subjective because they convey the characters’ feelings. Again, best to scotch that notion up front. Those techniques are projected outward from the character, and we observe them. Cinematic subjectivity goes inward.

One step at a time

Another distinction to stress early on is the basic one we make between film technique and function. There are a myriad of film techniques that could be used in either objective or subjective ways. To take a simple example, a low camera angle might indicate the POV of a character lying down and looking up at something; that’s perceptual subjectivity. A low angle of a skyscraper in an establishing shot might simply be the objective narration’s way of showing where a new scene will occur.

In contrast, indicating perceptual and mental subjectivity are two specific kinds of functions. Filmmakers can call upon whatever cinematic techniques they choose, and historically the more imaginative ones have shown immense creativity in trying to convey what characters see and think.

Some films depend heavily upon subjectivity, but objective narration is more common. There are many films that give us little access to characters’ perceptual and mental activities. Apart from The Big Sleep, there are films like Anatomy of a Murder, or virtually anything by Preminger. Most films use subjectivity sparingly. So let’s assume the students can tell that objective narration is the default.

With that out of the way, we can go back to basics. Both perceptual and mental subjectivity depend on being “with” the character in a strong way, as opposed to observing him or her as we would see another person in real life.

Perceptual subjectivity is fairly simple. The camera is in the character’s place, showing what he or she sees. The microphone acts as the character’s ears. Other characters present in the scene could step into the same vantage point and observe the same things.

So the test could run like this: As a viewer, when we see something in a film, is it really present within the scene? Could someone else in the same position see and hear the same things? Or is it a purely mental event, something no one else could see and hear, even if they stood beside the character or stepped into the place where that character had been standing?

If I were teaching the concept of narrational subjectivity as Film Art defines it, I would stress the notion of a continuum. After starting with very clear examples of both perceptual and mental subjectivity, I would progress to more ambiguous, mixed, or tricky instances.

Contributing to this discussion on the Filmies list, Chris Sieving, of the University of Georgia, says he shows a  clip from Lady in the Lake, the film noir where the camera always shows the POV of the detective protagonist. As Chris says, “It seems to effectively get across what perceptual subjectivity means (and how awkward it is in large doses), as well as what is meant by a (highly) restricted range of narration (as is the case with most whodunits).” As Chris also says, Lady in the Lake is a sort of limit case, a film that depends as much on perceptual subjectivity as it’s possible to do. (That’s “our” hand taking the paper in the shot at the right.) One could show several minutes from any section of the film and make the point thoroughly.

clip from Lady in the Lake, the film noir where the camera always shows the POV of the detective protagonist. As Chris says, “It seems to effectively get across what perceptual subjectivity means (and how awkward it is in large doses), as well as what is meant by a (highly) restricted range of narration (as is the case with most whodunits).” As Chris also says, Lady in the Lake is a sort of limit case, a film that depends as much on perceptual subjectivity as it’s possible to do. (That’s “our” hand taking the paper in the shot at the right.) One could show several minutes from any section of the film and make the point thoroughly.

There are other films that contain a lot of POV shots but intersperse them with objective ones. Rear Window is an obvious case. When Jefferies is alone, we see the courtyard events from his POV, a fact which is stressed by his use of binoculars and his long camera lenses to spy on his neighbors. This is clearly perceptual rather than mental. We never doubt that what we see through the hero’s eyes is real; we don’t believe that he’s making things up to entertain himself or because his mind is unbalanced. For one thing, there are two other characters who visit at intervals and see the same things that he does. We and they might question whether Jefferies’ interpretation of what he sees is correct, but we assume that the story’s real events have been conveyed to us through his eyes and ears. Only if we saw something like his fantasy of how he imagines his neighbor might have killed his wife would we move into the mental realm.

These two films foreground their use of POV. Usually, though POV shots are slipped into the flow of the action smoothly. Scenes of characters looking at small objects or reading letters often cut to a POV shot to help us get a look at an important plot element. At intervals during Back to the Future, Marty looks at a picture of himself and his siblings, gradually fading away to indicate that the three of them might never be born if he doesn’t succeed in bringing their parents together. It’s a simple way of reminding us what’s at stake and that Marty’s time to solve the problem is running out.

The Silence of the Lambs uses many POV shots and provides an excellent case of narration switching frequently and seamlessly between objective and subjective. Most of the POV views are seen through Clarice’s eyes, but sometimes through those of other characters. The first view of Lecter is a handheld tracking shot clearly established as what she sees as she walks along the corridor in front of the row of cells.

The scenes of Clarice conversing with Lecter develop from conventional over-the-shoulder shot/ reverse shot to POV shot/ reverse shot as both characters stare directly into the lens. (In Film Art, we use this device as an example of how style can shape the narrative progression of a scene [p. 307, 8th edition]). Other characters have POV shots as well, most noticeably, when Buffalo Bill twice dons night-vision goggles and we briefly see the world as he does.

Occasionally we see the POV of even minor characters, as when Lecter’s attack on his guard is rendered with a quick POV shot of Lecter lunging open-mouthed at the camera and then an objective shot of him grabbing the guard.

In their minds

Let’s jump to the other end of the continuum. Here we find a clear-cut use of mental subjectivity for fantasies, hallucinations, and the like. Obviously no one else present, unless he or she is posited as having special telepathic abilities, can see and hear what takes place only in a character’s mind.

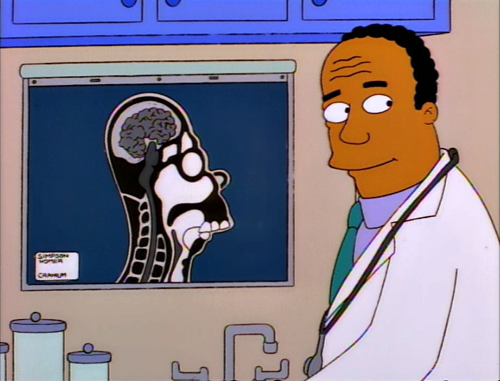

Such fantasies are a running gag on The Simpsons, where Homer’s misinterpretations, distractions, and visions of grandeur are shown either in a thought balloon or superimposed on his skull. In the example above, he abruptly starts “watching” a little cartoon after assuring Lisa that she has his complete attention. No one could mistakenly assume that these exist anywhere but in Homer’s imagination.

In Buster Keaton’s Our Hospitality, the hero receives a letter telling him he has inherited a Southern home. After an image of him thinking there is a dissolve to a view of a large, pillared house. Later, when he arrives at his small, ramshackle house, he stands staring in a similar situation, and here there is a fade-out to his dream house, which abruptly blows up. The humor in the second scene would be impossible to grasp if we didn’t easily understand that the shot of the house exists only in his mind.

Whole films can be built around fantasies. A large central section of Preston Sturges’ black comedy Unfaithfully Yours consists of a husband envisioning three different ways he might kill his supposedly cheating wife, all set to the musical pieces he is conducting at a concert. Fellini’s 8 ½ is only the most obvious example of how the art cinema often brings in fantasies. Other examples include Jaco van Dormael’s Toto le héros or Bergman’s Persona.

Once students have grasped the basic distinction between perceptual and mental subjectivity, it might be useful to emphasize the continuum by moving directly to its center, where the two types coexist.

The middle of the continuum: Ambiguity and simultaneity

Right in the middle of the continuum between the pure cases we find ambiguous cases. Filmmakers can create deliberate, complex, and important effects by keeping it unclear whether what we see is a character’s perception of reality or his/her imaginings.

1961 was a big year for ambiguous subjectivity, with two of the purest cases appearing. One was a genre picture, the other a controversial art film.

The first is the British horror film, The Innocents, directed by Jack Clayton and based on Henry James’s novella, The Turn of the Screw. In several scenes, a new governess at a country estate sees frightening figures whom she takes to be ghosts haunting the two children entrusted to her. We see these figures as she does, but we never see them except when she does. The children behave very oddly in ways that might be consistent with her belief, yet they deny seeing any ghosts. Finally the governess tries to force the little girl to admit that she also sees the silent female figure standing in the reeds across the water. Does the child’s horrified expression reflect her realization that the governess knows about her secret relationship with the ghosts? Or is she simply baffled and frightened by the governess’s increasingly frantic demands that she confess to seeing something that in fact she can’t see?

From the first appearance of the eery figures, the question arises as to whether the governess is imagining the ghosts or they are real, controlling the children, who try to keep them secret. There are apparent clues for either answer. By the end, we arguably are no closer to knowing whether the ghosts are real or figments of the heroine’s imagination.

Since Last Year at Marienbad appeared, critics have spilled gallons of ink trying to fathom its symbolism and sort out the “real” story that it tells. Clearly there are contradictions in events, settings, and voiceover narration. The second of the three accompanying images depicts the heroine as the hero’s voiceover describes their first meeting. They talked about the statue that stands beside her, seen against the formal garden of walks lined with pyramid-shaped shrubs. Yet another version of the first meeting starts, this time with the characters and the same statue against a background of a large pool. Later scenes in these locales display the same inconsistencies.

Are such contradictions the result of one character’s fantasies or of the conflicting memories that two characters have of the same event? Or are the contradictions not the products of subjectivity at all but just the playfulness of an objective, impersonal narration, manipulating characters like game pieces to challenge the viewer? (Our analysis of Last Year at Marienbad is available here on David’s website. It and all the Sample Analyses that have been eliminated from Film Art to make room for new essays are available here as pdf’s; the index to them is here, about halfway down the page.)

It’s not a good example of subjectivity to show students, but just as an aside, the screwball comedy Harvey is an interesting case, a sort of reversal of the Innocents situation. The narration withholds a character’s perceptual and mental events. Elwood P. Dowd describes what he sees and hears: a six-foot talking rabbit invisible to us and to all the other characters. The story concerns whether Dowd’s relatives will institutionalize him for insanity, and we assume along with them Harvey is a mere delusion. Thus the narration seems to be objective—or, the ending asks, has it been very uncommunicative, withholding something that the hero really does see and hear? True, throughout the film the framing leaves room for Harvey, as if he were there. One could argue, though, that these framings simply emphasize that the giant rabbit isn’t visible to us or the other characters and hence isn’t likely to really exist.

A film can easily present both perceptual and mental subjectivity at the same time. A POV shot may be accompanied a character’s voice describing his or her thoughts and feelings. Matthew shows his class part of the opening section of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, where a stroke victim’s extremely limited sight and hearing are rendered in juxtaposition with his voice telling of his reactions to his new situation. It is one of the most extensive and successful uses of such a combination in recent cinema, and it might be very effective in differentiating the two for introductory students.

A scene can also move rapidly back and forth between a character’s perceptions and his or her thoughts. Charlie writes that he shows his students the scenes of Marion Crane driving in Psycho. While the car is moving, almost every alternating shot is a POV framing of the rearview mirror or through the windshield. At that same time, we hear the voices of her lover, her boss, her fellow secretary, and the rich man whose money she has stolen while she imagines how they would react to her crime.

Showing scenes like these, where both types of subjectivity are used and clearly distinguishable might be more useful for students than showing several scenes that contain only one or the other.

Flashbacks, Voiceovers, and Altered States

In his original query to the Filmies, Matthew also said that students have problems with flashbacks: “Particularly, they resist the idea that a flashback is an example of subjective depth in general, even if the flashback unfolds objectively.” I can think of two ways to explain this.

First, classical films tend not to have flashbacks that just start on their own. To be sure, some do: a track-in to an important object and a dissolve can signal the start of a passage from the past, without a character being there. But more often a character is used to motivate the move into the past. A thoughtful look may do it, or a character may describe the past to someone else. In either case, the flashback is coming “from” the character and is assumed to show approximately what he or she is remembering. Occasionally the flashback may be a lie rather than objective truth, as we know from Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, The Usual Suspects, and a few other films.

In Poetics of Cinema’s third essay, David argues that most flashbacks in films are motivated as a character’s memory, but what is shown often strays from what he or she knew or could have known. He suggests that the prime purposes of most flashbacks is to rearrange the order of story events, and the character recalling or recounting simply provides an alibi for the time shift.

So we might think of character-motivated flashbacks as subjective frameworks that also contain objectively conveyed narrative information.

Second, the fact that flashbacks slip in objective information into characters’ memories is a convention. It’s a widely used method for presenting us with two things at once: first, a character’s memories and second, some story information that the viewer needs to have—even if the character couldn’t know about it. As we watch movies, we frequently accept conventions for the sake of being entertained. Beings that travel to Earth from distant galaxies speak English, high school kids can put together shows that wind up triumphing on Broadway, and people who drive up to buildings in crowded cities always find perfect parking spots. In a similar way, implausible mixtures of subjectivity and objectivity in flashbacks is just something we have to accept.

There are two other techniques that didn’t get mentioned during the discussion but that might confuse students.

What about shots showing the vision of a character who is drunk, dizzy, drugged, or otherwise unable to see straight? The most common convention is to include a POV shot that’s out of focus, perhaps accompanied by a bobbing handheld camera. Other characters in the scene, assuming they are not similarly impaired, would not see the surroundings in the same way.

Still, I think the same perceptual/mental distinction holds for such moments. The fuzziness and the lack of coordination are physical effects that are not being imagined by the character. They remain in the perceptual realm. Mental effects of impairment would be dreams or hallucinations. Some examples: the “Pink Elephants on Parade” sequence in Dumbo and the DTs vision of the protagonist of Wilder’s The Lost Weekend. As the title suggests, Altered States takes such mental activities as its subject matter and has many scenes that represent them.

A harder case is voiceover. Are all cases of voiceover subjective? Clearly not. If we have a situation where a character tells a story to a group and his or her voice continues over a flashback, the narration remains objective. We assume that the group can still hear the storyteller. Cases where the voice exists only in the mind, as when a character speaks to himself or herself, but not aloud, are mental subjectivity.

That said, there are many unclear cases. Just what is the status of the narration in Jerry Maguire? Jerry seems to speak directly to us, pointing out things that happen during the action, yet clearly there is no suggestion that he made the film we are watching. The problem is compounded in Sunset Boulevard, where the protagonist not only implicitly addresses us but is also dead. In many cases when a character’s voice is heard over a scene, it might occur to audience members to wonder where the character is or was when speaking these words. And does a character’s voice describing his or her feelings constitute objective or subjective narration? Probably we would want to say that only when the voice is posited as strictly an internal voice, audible only to the character, would we want to dub it subjective.

The problem with voiceovers arises, I think, because it’s such a slippery technique to begin with, and therefore often hard to categorize. Is a character speaking narration over events that happened in the past diegetic sound or nondiegetic? If there’s never an establishment of where and when that character does the narrating, he or she exists in a sort of limbo in between the two states: diegetic because he or she is a character, nondiegetic because he or she is in some ineffable way removed from the story world.

For voiceovers, then, I think it’s best simply to categorize the ones that obviously are straightforwardly objective or subjective. In tricky cases, we just have to admit that not all uses of film technique are easy to pin labels on. But the point of having categories like these isn’t to pin labels. In part knowing them allows us simply to notice things in films that might otherwise remain a part of an undifferentiated flow of images. They enable us to see underlying principles that make films into dynamic systems rather than collections of techniques. They give us ways to organize our thoughts about films and convey them to others. And, though students may doubt this, watching for such things becomes automatic and effortless once we have understood such categories and watched a lot of films. As a child, I don’t think I knew about the concept of editing or ever really noticed cuts. Now I’m aware of every cut in every film I see, and I notice continuity errors and graphic matches and other related techniques, all automatically, without that awareness impinging in the least on my following the story and being entertained. Learning the categories is only the beginning.

Playing with subjectivity

Once students have seen some clear cases of each type of cinematic subjectivity and understand the difference, the teacher could move on to emphasize that filmmakers can play with both in original ways. It’s not really possible in an introductory textbook to discuss all the possibilities—and probably not possible to come up with a typology that would cover every example of subjectivity that could exist across that continuum we mentioned. Imaginative filmmakers will always find new variants on how to use techniques for this purpose. But here are a few intriguing cases.

In his class, Chris shows the scene in Hannah and Her Sisters where the Woody Allen character, a hypochondriac, visits a doctor for some hearing tests. Initially the doctor comes into the room and gives a dire diagnosis of inoperable cancer. After Mickey has reacted to that, a cut takes us back to an identical shot of the doctor entering, but this time he gives Mickey a clean bill of health. The first part of the scene is retroactively revealed to have been a mental event, Mickey’s pessimistic fantasy.

The same sort of thing happens in a more extended way with the familiar “it was only a dream” revelations that make the audience realize that a major part of the plot has been subjective. In a more sophisticated way, as Chris points out, other sorts of mental subjectivity, usually lies or extended fantasies, can be revealed retrospectively, as in The Usual Suspects, Mulholland Drive, and Fight Club.

A flashback from one character’s viewpoint may reveal something new about an earlier scene. In Ford’s The Man who Shot Liberty Valance, the shootout is initially shown through objective narration. Only later in the plot does another character reveals that, unbeknownst to us or the other people present, he had also been present at the shootout. The flashback to his account reveals that the shootout happened very differently from the way we had assumed when first seeing it.

I’ll close with an example from The Silence of the Lambs. This shows how subtle and effective a play with perceptual and mental narration can be. In the scene at the funeral home where a recently discovered body of a murder victim is to be examined, Clarice is left waiting in the midst of a group of state troopers who stare at her. To get out of the situation, she turns and looks into the chapel, where a funeral is taking place. We see her face and then her POV as she surveys the room. A cut shows Clarice suddenly within the chapel, moving forward toward the camera and staring straight into the lens. We will only realize retrospectively that this image begins a fantasy that leads quickly into a memory. Clarice has not actually left her previous position just outside the door.

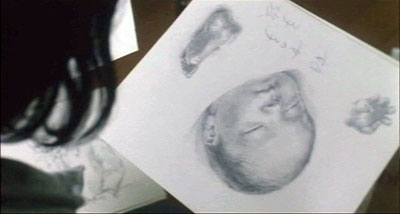

The next shot is a track forward through the center aisle toward the casket. Since Clarice had been walking in that direction before the cut, we recognize this as a POV and assume that Clarice is continuing to walk. Yet the man in the casket, as we soon will learn, is Clarice’s father. The shot represents a different funeral, one in the past which she has been triggered to remember by her glance into the chapel. The fantasy has become a flashback. A second, similar view of Clarice’s face returns us to her fantasizing adult self, the one remembering this scene but not the one still standing outside the door. A closer view of the father’s casket shows it from a lower vantage-point, as if that of a child.

The reason for the change becomes apparent from a radical change at the next cut, so that the camera is on the far side of the casket, filming from a low angle. The sudden shift moves us away from the adult Clarice in order to show her as a child approaching her father and leaning down to kiss him. A noise pulls Clarice out of her memory, and a cut back to the hallway shows her turning away from the chapel. (As often happens, sound, and particularly music, helps guide us through the scene, marking the beginning and ending of the fantasy/flashback.)

The most experienced film specialist could not track all the rapidly shifting levels of subjectivity in this scene on first viewing. Still, later analysis using some categories of subjective narration can help us appreciate how Demme has woven them into a scene that helps explain Clarice’s motives in becoming an FBI agent and her determination in pursuing her first case.

Categories matter

To some students, the categories I’ve just discussed may seem like trivial distinctions. They’re not. The use of subjective narration is one of the key ways the filmmaker has to engage our thoughts and emotions with the characters. In Psycho, we become involved in Marion Crane’s life in a remarkably short time, partly because of her situation but also partly because Hitchcock keeps us so close to her once she prepares to steal the money. The camera not only frames her closely, but to a considerable degree we see and imagine what she does: her fearful forebodings of how her rash act will turn out. Much the same thing happens with Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs, though there our emotional involvement lasts throughout the film, and we are given glimpses of Clarice’s memories.

Perhaps choosing a scene or two from such films and going through them with the students, trying to imagine what it would be like without the POV shots and the imaginings and the memories, would convince them of the value of learning these categories. After all, the exceptions they find are only exceptional because they play in a zone defined by solid concepts.

[Note added October 24: I should have referred back as well to David’s entry “Three Nights of a Dreamer,” largely on POV.]

Objective

Women and children first

Ten AM on a Tuesday, and I’m at my local megaplex, Star Cinema. I’m here to not to see a movie, exactly, but to catch a phenomenon I’ve been curious about for some years.

To back up: Kristin and I have fallen a bit behind in our blogging. For one thing, the presidential election has been so exciting that we spend more time staring at cable news than ever before. (But the time hasn’t been wasted: the campaigns have given me an idea for a blog entry, which I hope to post next week.) Secondly, we’ve been going over the copy-edited version of the third edition of our textbook, Film History: An Introduction. It’s due out this spring, and we’ll have more to say about it later. If you want a preview now, check the new essay I posted elsewhere on this site. It’s called “Doing Film History,” and it’s an updated version of the introduction that appeared in earlier editions of FH.

Kristin has been laboring over an epic blog on character subjectivity. As for me, to take a break from both politics and the textbook, I headed to Star.

The youngest demographic

The phenomenon I was interested in goes by different names, but here in Madison it’s called Baby Box Office.

Every Tuesday morning Star runs screenings for parents and their pre-schoolers. It’s billed as a chance to bring your child to see a film in a welcoming setting. The theatre is a little more illuminated than normal, the sound a little softer. Nobody will ask the kid to shush; you can even nurse your baby. Incidentally I hope that this gets babies to associate movies with oral gratification. The future needs passionate filmgoers, not to mention film students.

You can get more details from the Kerasotes chain’s website, and they’re pretty interesting. (Some theatres offer a Stroller Valet Service.) So I got curious and headed to the ‘plex.

I was surprised that five films were lined up to be screened—not Saw V and Max Payne, naturally, but a fairly wide range, including W. and a couple of animated titles. If none of the customers chooses a film, it’s not run. I asked which movie was today’s top pick, and Susan the cashier suggested The Secret Life of Bees. Buying my ticket, I met Meg and her son Connor. I asked whether she came often. With a smile, she said: “It’s been a life-saver.” She regularly meets a friend, who also has an infant, at the show.

Outside the auditorium there was a changing cot, with baby powder at the ready. Somehow, knowing it was there comforted me.

I counted twelve non-kids at the show, including a guy more or less like me (graying, maybe retired) and three young women who might have been playing hooky from high school. The show was an ordinary screening. There were local ads and video commercials. There were trailers for upcoming releases The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (Nazis with, natch, British accents), Marley and Me (a dog running in surf), The Soloist (Oscar bait), and Australia (part African Queen, part Out of Africa; I gather that She Will Fall in Love with a Man. . . and a Country).

I wish I could report that a dramatic incident, or at least an epiphany, took place during my visit. But the kids were mostly quiet. Occasionally I heard a wail or gurgle, and at one point a mother took a fretful baby out. The screening went fine. Glancing at the kids, I saw many of them staring at the screen transfixed and uncomprehending. On the basis of this experience, I’ve decided it’s better to have a squad of babies in a theatre than a few teenage boys.

As for The Secret Life of Bees: Cynics will say it’s ready for the Hallmark Channel, but I liked it. It’s what the Japanese call a “wet” film, affording many occasions for tears, in which I freely indulged. Not of much pictorial interest, it is saved, at least for me, by a robust script (tailored to Kristin’s four-part template), solid performances, and sentimental situations centering on racism, child abuse, female bonding, and raging male inadequacy. Needless to say, thanks to intensified continuity a lot of reaction shots drive home each moment. Appropriately, the mommy audience was seeing a movie about mommies; the idealistic but forlorn little heroine winds up with three, at least.

Afterwards, I talked to a pair of ladies who had brought a toddler. While he wrestled with the steering wheel on an arcade driving game, they explained that they frequently come to the shows and are glad that Star Cinema offers them the option. I then talked at length with Star’s savvy general manager, Craig Hussin, who has been part of the Madison movie scene for many years. Craig sees Baby Box Office as part of what every theatre should do—offer the patrons many options, and do it with the sort of flair that used to be called showmanship.

Mom, dad, and dollars

Susan Hansen, Meg Teter, and Connor.

There’s a broader point of interest to us as students of cinema. I think that the phenomenon is a good example of market segmentation, which David Waterman has talked informatively about in Hollywood’s Road to Riches. (1)

Obviously, people’s preferences about movies, as about anything else, differ. Some people want to see a movie the day it’s released; others are willing to wait a while. So it’s better business to charge the eager consumer more than the more cautious one. This is a form of price discrimination.