Archive for November 2008

His majesty the American, leaping for the moon

DB here:

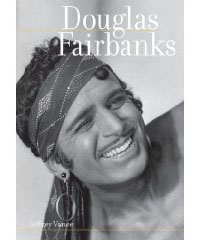

Douglas Fairbanks is remembered today as the nimble, insouciant hero of a string of swashbuckling films: The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), The Thief of Baghdad (1924), Don Q Son of Zorro (1925), and The Black Pirate (1926). He is the primary subject of a gorgeously illustrated, solidly researched new biography by Jeffrey Vance with Tony Maietta. Proceeding film by film, the authors interweave his life story with production data and summaries of critical reception. While tracing his career, they make an intriguing case that Fairbanks’ 1920s features more or less founded the modern film of action and adventure.

Douglas Fairbanks is remembered today as the nimble, insouciant hero of a string of swashbuckling films: The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), The Thief of Baghdad (1924), Don Q Son of Zorro (1925), and The Black Pirate (1926). He is the primary subject of a gorgeously illustrated, solidly researched new biography by Jeffrey Vance with Tony Maietta. Proceeding film by film, the authors interweave his life story with production data and summaries of critical reception. While tracing his career, they make an intriguing case that Fairbanks’ 1920s features more or less founded the modern film of action and adventure.

In the five years before The Mark of Zorro, Fairbanks made twenty-nine features and shorts. Vance and Maietta are enlightening on this period, but they treat it as prologue to the more spectacular work. Now, as if to counterbalance their book, comes a new Flicker Alley DVD collection, Douglas Fairbanks: A Modern Musketeer, gathering ten of the early films along with a very pretty copy of The Mark of Zorro and Fairbanks’ last modern-day movie, The Nut (1921), made because he wasn’t sure that Zorro would be a hit. (It was.) To the DVD package Vance and Maietta have contributed an informative booklet and they offer enlightening conversation in a commentary track for A Modern Musketeer (1917).

Kristin and I have long been fans of the pre-Zorro titles. Kristin wrote an appreciation of the early films for a Pordenone catalogue, and I studied Wild and Woolly (1917) as an early prototype of Hollywood narration. (1) There’s no denying that the 1920s costume pictures offer dashing spectacle and derring-do. But the 1915-1920 films are something special—lively, lilting, and unexpectedly peculiar. (2)

Kristin and I have long been fans of the pre-Zorro titles. Kristin wrote an appreciation of the early films for a Pordenone catalogue, and I studied Wild and Woolly (1917) as an early prototype of Hollywood narration. (1) There’s no denying that the 1920s costume pictures offer dashing spectacle and derring-do. But the 1915-1920 films are something special—lively, lilting, and unexpectedly peculiar. (2)

Before he became Fairbanks, he was Doug, the relentlessly cheerful American optimist. This star image was created very quickly, in films and in public events that made him seem the nicest guy in the country. His manic energy came to incarnate the new pace of American cinema, and his films helped shape the emerging precepts of Hollywood storytelling.

Doug

Consider his contemporaries. William S. Hart keeps his distance; perhaps his severe remoteness comes from secret pain. The result is a man you respect and admire but can hardly love. Mary Pickford, though, is lovable, and so is Chapin, although his cruel streak complicates things. But Doug is quintessentially likable. His early films present us with a brash youth who is all pep and pluck, bouncing with barely contained energy, unselfconscious in his engulfing enthusiasm for life. Today he could be elected President, the ultimate guy to have a beer with. (In real life Fairbanks was a teetotaler.)

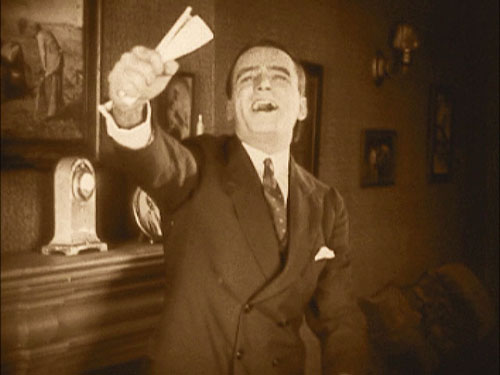

There is no guile in him, no hidden agenda. When he’s brimming with delight, as he often is, he flings his arms out wide. In another actor this would be hamminess, but for Doug it’s simply an effort to embrace the world. Any social embarrassments he commits—and they are plenty—he acknowledges with a puzzled frown before flicking on an incandescent grin. Who else makes movies with titles like The Habit of Happiness (1916) and He Comes Up Smiling (1918)?

There is no guile in him, no hidden agenda. When he’s brimming with delight, as he often is, he flings his arms out wide. In another actor this would be hamminess, but for Doug it’s simply an effort to embrace the world. Any social embarrassments he commits—and they are plenty—he acknowledges with a puzzled frown before flicking on an incandescent grin. Who else makes movies with titles like The Habit of Happiness (1916) and He Comes Up Smiling (1918)?

But how can such a genial fellow yield any drama? Give him an idée fixe, a cockeyed hobby or life philosophy into which he can pour his adrenaline. Now add a goal, something that his obsession blocks or unexpectedly helps him attain. Toss in the staples of romantic comedy: a good-humored maiden uncertain how to tame this creature of nature, a few old fogeys, some unscrupulous rivals. Hardened crooks may make an appearance as well. Be sure to include some tables, chairs, sofas, or horses for him to vault over, as well as some perches near the ceiling or on the roof; Doug feels most comfortable lounging high up. Add windows, for his inevitable defenestration. (In a poem about him, Jean Epstein wrote, “Windows are the only doors.”) There should also be chases. Other comedy stars run because they must. Doug’s joy in flat-out sprinting suggests that he welcomes the chance to flush a little hyperactivity out of his system. At the story’s climax he must save the day, taming his obsession and achieving his purpose while acceding to the claims of the practical world.

An early example is His Picture in the Papers (1916). In this satire on vegetarianism and the American lust for publicity, Doug works for his father’s health-food firm, even though he prefers thick steaks. But he’s full of ideas for promoting the product. Doug needs money to marry his equally carnivorous girlfriend, but his father will give him the dough only if Doug can pitch their line of dietary supplements. Doug vows to get his picture in every newspaper in town. While he launches a series of high-profile stunts—wrecking his car, entering a prizefight, brawling on an Atlantic City beach—his sweetheart’s father is pursued by a gang called the Weazels, who try to extort money from him.

The two plotlines converge, with Doug stopping a train wreck and winning a place on the front pages. (In a sly dig at the press, each news story contradicts the others.) The movie is a little disjointed, but several scenes are remarkable, not least a boxing match in an actual athletic club before an audience of cheering Fairbanks pals. And there is more than one funny framing, notably a nice planimetric one showing all our principals lined up and reading different newspapers celebrating Doug’s triumph.

As the title indicates, in The Matrimaniac (1916) Doug’s goal is elopement, which he pursues obsessively. He evades a rival suitor, his girlfriend’s father, a sheriff, and a posse of city officials in order to tie the knot in a gag that must have looked radically up-to-date. Reaching for the Moon gives us a more philosophical Doug, a naive disciple of self-help books that urge him to strive, to concentrate, and above all to keep his eye on the most supreme goal he can imagine. He ends up in New Jersey.

Wild and Woolly (1917) casts Doug as the son of a railroad tycoon. Although he lives in Manhattan, he dreams of being a cowboy. His bedroom boasts a teepee, and he practices his roping skills on the butler. Sent out to Bitter Creek to investigate a deal, he encounters the rugged frontier of his dreams, complete with shootouts, town dances, and hard-drinking cowpokes. But all of this is a show, staged by the locals to make him look favorably on a railroad spur. In another twist, a crooked Indian agent uses the charade to rob the bank and stir up an Indian settlement. Now Doug’s obsessions prove really useful, as his cowboy skills rescue the town.

Wild and Woolly is among the very best of the surviving early Fairbanks titles, and its adroit storytelling is still admirable today. The best-known version was a very poor print, salvaged from the Czech archives and still circulating on barely visible VHS and public-domain DVD copies. Forget those. On the Flicker Alley collection the image quality, while not perfect, allows this trim little masterpiece to be appreciated. (3)

“Always chivalrous, always misunderstood,” reads one intertitle in another gem, A Modern Musketeer. Here Doug is possessed by the spirit of D’Artagnan, simply because while he was in the womb his mother was reading The Three Musketeers. He manages to live up to his heritage as he overcomes a philandering rival and a bloodthirsty Indian. The climactic chase takes place at the Grand Canyon, affording Doug a chance to shinny up and down cliffs and do handstands along a precipice.

Doug never does things by halves. In Flirting with Fate, he is a starving artist, out of money and apparently unloved by his girl. The logical solution is to hire a killer to end his misery. Of course Doug’s fortunes instantly change, and life becomes worth living, but then he must somehow find his assassin and call off the hit.

Many of the early films show the protagonist fully formed as a cross between a cheerleader and a track star. But Fairbanks made a big success on stage playing a sissy. The task in such a plot is to turn him into a red-blooded man. His first film, The Lamb replayed this lamb-into-lion plot, which also served as the basis for Buster Keaton’s first feature, The Saphead (1920).

In the Flicker Alley collection, this strain of Doug’s work is represented by The Mollycoddle (1920). Doug is the descendant of hard-bitten westerners, but growing up in England has made him a fop. Coming to America with a batch of wealthy Yanks, he is a continual figure of fun, waving his monocle and cigarette holder. Once in Arizona, however, he’s confronted with a diamond-smuggling racket. He starts to channel his ancestors and turns into a hell-for-leather hero. He allies with a tribe of exploited Indians to capture the gang, in the process indulging in leaps, falls, canyon-scaling, and fistfights in raging rapids.

The titles often invoke craziness, vide the Matrimaniac, The Nut, and Manhattan Madness (1916). But this motif is carried to an extreme in one of the strangest pictures of the still-emerging Hollywood cinema. When the Clouds Roll By (1919) crams in enough gimmicks for three Doug stories. First, our hero is neurotically superstitious. He will climb over a building to avoid letting a black cat cross his path. He meets a girl who is as superstitious as he is, so after a session at the Ouija board, they seem a good match.

At the same time, however, a psychiatrist is making Doug the subject of a demonic experiment: Can one drive a person to madness and suicide? Through bribes and surveillance, Dr. Metz turns Doug’s life into hell—botching his romance, getting him disowned by his father, and even inducing nightmares. As if all this weren’t enough, the last reel jams in a train crash, a bursting dam, and a flood. Before this overwhelming climax, When the Clouds Roll By isn’t so much funny as eerily paranoiac. The way Dr. Metz’s Mabuse-like scheme enfolds everyone is as anxiety-provoking as anything in a film noir. This dreamlike movie ends on a surrealist note: Doug and his sweetheart get married when flood waters carry a church past them.

At the same time, however, a psychiatrist is making Doug the subject of a demonic experiment: Can one drive a person to madness and suicide? Through bribes and surveillance, Dr. Metz turns Doug’s life into hell—botching his romance, getting him disowned by his father, and even inducing nightmares. As if all this weren’t enough, the last reel jams in a train crash, a bursting dam, and a flood. Before this overwhelming climax, When the Clouds Roll By isn’t so much funny as eerily paranoiac. The way Dr. Metz’s Mabuse-like scheme enfolds everyone is as anxiety-provoking as anything in a film noir. This dreamlike movie ends on a surrealist note: Doug and his sweetheart get married when flood waters carry a church past them.

Across these films, in fact, the Fairbanks persona starts to disintegrate. Somewhat like those naïve Capra heroes of the 1930s (Mr. Deeds, Mr. Smith) who turn into melancholy victims in Meet John Doe and It’s a Wonderful Life, Doug becomes more brooding and helpless. In Reaching for the Moon, his absurd dream of glory is revealed as just that, a dream. When the Clouds Roll By saves itself from despair through splashy last-minute rescues.

Fairbanks was evidently becoming uncomfortable in cosmopolitan comedy. His taste for large-scale stunts and tests of prowess led him to the costume sagas of the 1920s. In the process, as Vance and Maietta point out, he cleared the way for Keaton and Harold Lloyd. Both comics would sometimes play obtuse idlers in the Lamb mode, and both would take thrill comedy to new heights. But avoiding Fairbanks’ ebullient optimism, Keaton brought a perplexity to every situation, along with an angular athleticism and a geometrical conception of plotting and shot composition. Lloyd frankly presented a hero lacking social intelligence, afflicted with a stammer or shyness or even cowardice, always desperate to fit in. Both men deepened the possibilities of modern-day comedy, thriving in the niche vacated by Fairbanks.

Bug and Mr. E

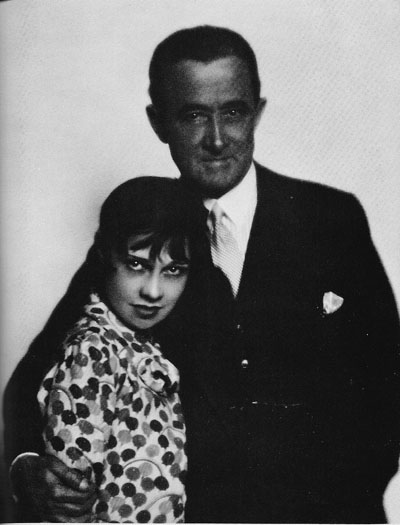

For nine of the early films, Fairbanks had the help of John Emerson and Anita Loos. All three worked on the stories, with Emerson usually directing and Loos writing the scripts and intertitles. The collaboration lasted only about two years, but it yielded some definitive moments in the creation of the Doug mystique.

Emerson found his first success acting and directing on the New York stage. Under Griffith’s supervision he started filmmaking in 1914, with an adaptation of his own successful play, The Conspiracy. I haven’t seen this or most of his other early work, but his 1915 Ibsen adaptation Ghosts, codirected with George Nichols, betrays little of the dynamism that would run through his Fairbanks projects (although The Social Secretary of 1916, without Doug, is lively enough). Emerson continued to direct films and New York stage productions until his death in 1936, at the age of fifty-eight.

Loos was a tiny prodigy. She sold her first scripts at age nineteen, with the third, The New York Hat (1913), directed by Griffith, earning her twenty-five dollars. (Her punctilious account book is reprinted in her 1974 autobiography Kiss Hollywood Goodbye.) After writing scores of shorts, she moved into features in 1916, when, she claims, Emerson discovered her script for His Picture in the Papers. Clearing the project with Griffith and casting Doug Fairbanks, the team proceeded. This, Fairbanks’ third feature, proved a great success and solidified important aspects of his star persona.

Loos married Emerson, whom she recalled as having “perfected that charisma, which even a bad actor has, of being able to charm his off-stage public.” (4) He called her Bug, she called him Mr. E., and they became a Hollywood couple. They kept themselves before the public eye with interviews and books like How to Write Photo Plays (1920) and Breaking into the Movies (1921). These are full of information about the filmmaking practices of the day.

Loos married Emerson, whom she recalled as having “perfected that charisma, which even a bad actor has, of being able to charm his off-stage public.” (4) He called her Bug, she called him Mr. E., and they became a Hollywood couple. They kept themselves before the public eye with interviews and books like How to Write Photo Plays (1920) and Breaking into the Movies (1921). These are full of information about the filmmaking practices of the day.

Why did Emerson and Loos split from Fairbanks? Loos says that that Doug had become somewhat jealous of her notoriety. (5) Further, the couple yearned to return to New York. There Loos would hobnob with the Algonquin club crowd and write Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, a successful serial, book, play, and silent film. Eventually she would write plays and return to Hollywood as an MGM screenwriter.

Although they remained married and collaborated on plays and films, the pair eventually lived apart, the better to ease Emerson’s philandering. “Mr. E.’s devotion was largely affected by the amount of money I earned,” Loos recalled. (6) By her own testimony, she earned plenty. She writes in 1921:

The highest paid workers in the movies today are the continuity writers, who put the stories into scenario form and write the “titles” or written inserts. The income of some of these writers runs into hundreds of thousands of dollars a year . . . . Scenario writing does not require great genius. (7)

Loos is largely credited with bringing the witty intertitle into its own. Expository “inserts” were often neutral descriptions of the action or pseudo-literary ruminations. Loos created intertitles that were amusing in themselves. When Jeff, the hero of Wild and Woolly, comes to Bitter Creek he’s delighted to find a rugged life matching the one he mimicked in his East Coast mansion. So naturally Loos’ title reads, “All the discomforts of home.”

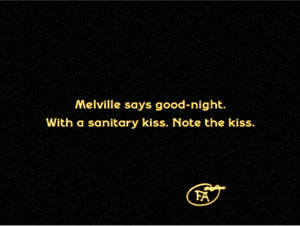

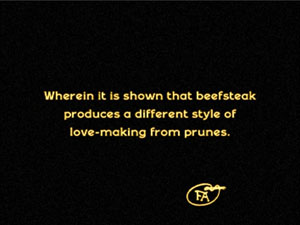

She wedged in puns, satiric jabs, and asides to the audience. The vegetarianism portrayed in His Picture in the Papers makes for anemic romance. Loos’ title prepares us:

The young suitor and Christine kiss by tapping each other’s cheek with their fingertips.

Later the intertitle stresses the more robust wooing program launched by Doug.

By the time Loos and Emerson left Fairbanks, the look and feel of their contributions had been mastered by others, notably director Allan Dwan, and smart-alec intertitles continued to grace Fairbanks’ modern comedies. Throughout the 1920s, most comedies would strive, not always successfully, for the cleverness Loos brought to the task. My own favorite in her vein comes in the Lloyd vehicle For Heaven’s Sake (1926). Harold is a millionaire courting a girl working in her father’s mission house in the slums, and one of the titles refers to “The man with a mansion and the miss with a mission.” Such niceties largely vanished when movies started to talk.

Cutting edge

We can learn a lot about the history of Hollywood from these films too. In the 1910s, narrative techniques were being put in place: the goal-oriented hero, the multiple lines of action, the need to prepare what will happen later, the use of motifs as running gags. At the start of The Matrimaniac, we see Doug sneaking into a garage and letting the air out of a car’s tires. Only later, after he has eloped with the daughter of the household, do we realize that this was a way to keep her father from pursuing them. In the course of the same film, the elopement is aided by passersby, and Doug keeps scribbling IOUs to pay them. At the end, the parson who has helped the couple the most is rewarded by the biggest payoff, with Doug shoveling bills at him.

The same years saw the consolidation of the “American style” of staging, shooting, and cutting scenes. (For more on this trend, see our earlier entries here and here.) Fairbanks’ films from 1916 to 1920 display a growing mastery of continuity techniques; the style coalesces under our eyes.

The system depended on breaking up master shots into many closer views. This practice was less common among European directors of the time, who might supply inserts of printed matter like letters but did not usually dissect the scene into shots of different scales. In His Picture in the Papers, for instance, we get a master shot (nearer than it would be in a European picture) of Melville paying court to Christine, followed immediately by closer views that show their expressions.

This is a minimal case. Not only are the shots all taken from the same side of the line of action (the famous 180-system) but they are taken from approximately the same angle. Filmmakers sometimes varied the angle more, usually to indicate a character’s point of view but sometimes to bring out different aspects of the action. (See here for examples from William S. Hart.)

Very quickly directors realized that you didn’t need a master shot if you planned your shots carefully. In Flirting with Fate, the artist Augy is chatting with Gladys, while her mother and her rich suitor watch from another part of the room. No long shot presents both pairs.

The mother summons Gladys, and when she and Augy rise, director Christy Cabanne cuts to another shot of them, moving into the frame.

This is a very rare option in most national cinemas of the period, which would simply frame the couple in a way that allowed them to rise into the top of the same shot. Now Gladys hurries out, crossing the frame line. This exit matches her entrance on frame left, meeting her mother.

Such a scene is obvious by today’s standards, but a revelation at the time—a way of lending even static dialogue scenes a throbbing rhythm that absorbed viewers. Around the world, notably in the Soviet Union, young directors saw this as the cutting-edge approach to visual storytelling. The new style was as probably as exciting to them as the powers of the Internet are in our time.

Because of analytical editing, the cutting pace of American films of the late 1910s is remarkable, and the Fairbanks films, with their strenuous tempo, are fair examples; the average shot length in these films ranges between 4 seconds and 6.6 seconds. With so many shots, production procedures emerged to keep track of them. To a certain extent shots were written into the scenarios Loos refers to, but directors also broke the action up spontaneously during filming. The cameraman, and later a “script girl,” would log the shots during shooting so that they could be assembled correctly in the editing phase.

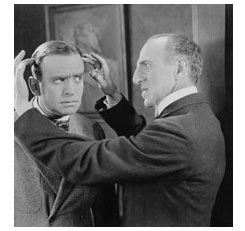

Directors were still refining the system, though, as we can see from an awkward passage of shot/ reverse shot in A Modern Musketeer.

The eyelines are a bit out of whack, but odder still are the identical backgrounds of the two shots. Evidently director Allan Dwan made these shots quickly and closer to the canyon rim, in the expectation that nobody would notice the disparity.

Point-of-view shots were easier to manage, and they could intensify the drama. Later in A Modern Musketeer, the rapacious Chin-de-dah tells the white tourists he’s getting married. To whom? asks Elsie. Instead of answering, “You,” he holds up his knife.

Sometimes you suspect that filmmakers were multiplying shots just for the fun of it. The early Fairbanks films are vigorous to the point of choppiness; action scenes spray out a hail of images, some offering merely glimpses of what’s happening. Wild and Woolly is especially frantic, with the final sequences of kidnapping, gunplay, and a ride to the rescue breathless in their pace. In the course of it, Emerson realizes that fast action needs some overlapping cuts to assure clarity. Doug bursts through a locked door in one shot, and from another angle, we see the door start to open again.

Only a few frames are repeated, but the movement gains a percussive force. Doubtless the Russians studied cuts like this; Eisenstein made the overlapping cut part of his signature style.

By contrast, The Mark of Zorro and its successors have calmer pacing. Doug’s acting got more restrained too, with his bounciness largely confined to the action scenes. Already in 1920, high-end pictures were finding a more academic look, a polished and measured style. Dialogue titles became more numerous, and big sets and other production values were highlighted.

I’ve been able to sample only a few points of interest in the early Fairbanks output. I haven’t talked about Fairbanks’ foray into Sennett-style farce, the cocaine-fueled Mystery of the Leaping Fish (1916), or the bold experimentation of the cinematography in the dream sequence of When the Clouds Roll By. My point is just to note that these films radiate exuberance—not only in their hero but in their very texture. Scene by scene, shot by shot, Doug’s energy is caught by an efficient, pulsating style that was an engaging variant of what would soon become the lingua franca of cinematic storytelling.

For other reading on Fairbanks, you can consult Alastair Cooke’s Douglas Fairbanks: The Making of a Screen Character (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1940), one of the earliest and still most thought-provoking studies; John C. Tibbetts and James M. Welsh’s His Majesty the American: The Films of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (South Brunswick, NJ: A. S. Barnes, 1977), which is wide-ranging and strong on the early films; Booton Herndon’s Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks (New York: Norton, 1977); and Douglas Fairbanks: In His Own Words (Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2006), a collection of interviews and essays signed (but probably mostly not written) by the star. I’ve also been enlightened by Lea Jacobs’ essay “The Talmadge Sisters,” forthcoming in Star Decades: The 1920s, ed. Patrice Petro (Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, forthcoming). Online, there is much information at the Douglas Fairbanks Museum site.

(1) Kristin Thompson, “Fairbanks without the Mustache: A Case for the Early Films,” in Sulla via di Hollywood, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (Pordenone: Biblioteca dell’Immagine, 1988), 156-193; David Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 166-168, 201-204.

(2) This set is very well chosen, but there are enough other films surviving from this period to warrant another box. It could include The Lamb (1915), Double Trouble (1915), The Good Bad Man (1916), Manhattan Madness (1916), The Americano (1916), Down to Earth (1917), The Man from Painted Post (1917), His Majesty the American (1919), and The Half Breed (1916), in which Fairbanks plays a biracial hero. On the matter of race, the films in the collection aren’t free of condescension and stereotyping, but there are also moments of affection between Fairbanks and Native Americans. He had extraordinarily dark skin, a fact he apparently took in his stride.

(3) I believe that this print is from a different version than the one I’ve known before; a few shots seem to show slightly different angles. (Perhaps the earlier one was from a foreign negative?) An informative page of the Flicker Alley booklet signals the provenance of the prints. While I’m on the subject, I should mention that occasionally the framing seems a bit cropped, but that could be due to the source material.

(4) Loos, Kiss Hollywood Goodbye (New York: Ballantine, 1974), 2.

(5) Loos’ account of the break with Fairbanks can be found in her memoir, A Girl Like I (New York, 1966), 178. You have to admire a book that ends with the line, “Miss Loos, you sure are flypaper for pimps!”

(6) Loos, Kiss Hollywood Goodbye, 14.

(7) Emerson and Loos, Breaking into the Movies (Philadelphia: Jacobs, 1921), 43.

When the Clouds Roll By.

PS 30 Nov: Internets problems and a memory lapse kept me from mentioning two other important books on Anita Loos: Gary Carey’s lively biography Anita Loos (Knopf, 1988) and Anita Loos Rediscovered: Film Treatments and Fiction, ed. and annotated by Cari Beauchamp and Mary Anita Loos (University of California Press, 2003). Both Carey and Beauchamp echo Loos’ claims that the couple split from Fairbanks because he was somewhat envious of the attention they received, while Carey adds that Fairbanks wanted to break out of the “boobish” parts Loos wrote for him (p. 50).

PPS 8 Dec: Mea culpa again. I overlooked Richard Schickel’s book-length essay, His Picture in the Papers: A Speculation on Celebrity in America, Based on the Life of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (New York: Charterhouse, 1973). It’s a lively and thoughtful argument that Doug was one of the very first modern celebrities, and one who enjoyed his role as such.

It’s the 80s, stupid

Choose Me.

DB here:

In an earlier post, I proposed that film historians can’t safely assume that decades mark off meaningful periods. Yet I can’t help succumbing to the temptation myself. It happens every time I hear about how the 1970s were the last great decade in American film.

We’re often told that back then, countercultural forces gave us movies of restless auteur ambition like Five Easy Pieces and Nashville and Mean Streets and Shampoo. Meanwhile, The Godfather, Jaws, American Graffiti, and even Star Wars not only rejuvenated the studio system but also reflected something of their directors’ temperaments, providing Hollywood with an enduring new mythology. So far, so plausible.

Then, the story goes, came the age of the blockbuster. Thereafter, moviemaking was simply selling out, winning the weekend, building franchises, and catering to disposable teenage income. Like big hair and padded shoulders and Wham!, the films of the 1980s are apparently something to be ashamed of.

The glorious burnout

This judgment is spelled out most fully in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders and Raging Bulls, a celebration of and postmortem on the Movie Brats era of the 1960s-1970s. Biskind doesn’t try to make a critical case for the films of the period; he assumes that everyone counts these movies as edgy masterpieces. He’s more interested in the sensational lifestyle of the filmmakers. Filling his pages with gossip about alcohol, cocaine, backbiting, squabbles, and the horizontal mambo, he could hardly deny that his favorite directors were somewhat self-destructive. He justifies their escapades by treating them as driven artists fighting a corrupt system—mavericks, in fact. (Yes, he uses the word.) This idealization occasionally leads to mawkishness that Biskind would castigate if he saw it on the screen:

Hal Ashby did die just after Christmas, on a raw, rainy Tuesday. . . .The papers said it was liver and colon cancer, but it could just as well have been a broken heart. (1)

Forgiving the flaws of these all-too-human directors, Biskind spares no sympathy for the producers who focused on the bottom line. With rising budgets and distribution costs, the studios’ cynical leaders chose to play safe with megapictures that purveyed “smarmy, feel-good pap.” (2)

It’s a good, simple story, and the problem is the simplicity. The top-grossing movies of the 1970s include Love Story, Fiddler on the Roof, The Sting, The Towering Inferno, Rocky, Grease, Smoky and the Bandit, and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. These aren’t exactly testaments to personal expression. The megapicture mentality we associate with the 1980s was already present in some of these, as well as in The Poseidon Adventure, Earthquake, and Superman. The four-quadrant movie was taking shape well before Heaven’s Gate brought auteur ambitions crashing to earth.

Further, not every 1980s movie aimed to be a blockbuster. I tried to argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It that just as in the classic studio era, we have to look for creativity beyond the titles that dominate the best-10 and top-grosser list. In addition, there are always filmmakers whose sensibilities naturally match the demands of big-budget projects: David Lean and Anthony Mann managed it in the 1960s, Spielberg and Lucas in the 1970s. In the 1980s several directors were able to make strong, original megapictures.

So you can make a good case that the 1980s gave America a burst of first-rate films and remarkable new talent. At all levels, from ambitious prestige items to dazzling genre pictures, the decade is nothing to be sneezed at. The maw of home video had to be fed, so the demand was for product of all sorts. Videotape rental expanded specialty niches and cult markets. Filmmakers could finance projects through video and foreign presales, and investors took chances at many levels. The era saw a revival of ambitious independent films, which played alongside program pictures, Oscar bait, and summer blockbusters. Romantic comedy, action movies, and science fiction enjoyed a strong run. And many of the people we still consider genuine movie stars—Tom Hanks, Julia Roberts, Glenn Close, Harrison Ford, Mel Gibson, and Tom Cruise—are ineluctably creatures of the 80’s.

My defense doesn’t spring from generational bias. I don’t have the excuse of adolescent nostalgia that makes Tom Shone write:

What a grand piece of historical luck it was to be in your early teens when Raiders of the Lost Ark came out—when Spielberg and Lucas were in their prime and the very act of going to the movies seemed to come with its own brassily rousing John Williams score. Later on, we would learn to cuss and curse the infantilization of the American film industry, just like everyone else, but back then we were too busy infantilizing it to notice. (2)

So here are some assorted, more or less objective reasons to consider this decade as making a remarkable contribution to U. S. film history.

New talents, old genres

Near Dark.

Put aside two highly influential 1980s films, E. T.—The Extraterrestrial and Raiders of the Lost Ark, since Biskind would consider them feel-good pap. Put aside Raging Bull, which he grants canonical status as the capstone masterwork of the 1970s generation. Even granting all this, most major 1970s directors didn’t vanish in the megapicture decade.

Scorsese’s underrated King of Comedy was a portrait of a social type, the obstinate, delusional nerd; we all knew one, but we hadn’t seen him on the screen before. Altman moved from Popeye, a sort of anti-musical and anti-comic-book movie, to intimate theatre pieces like Streamers and Secret Honor and Fool for Love.

From Jonathan Demme we had Melvin and Howard and Something Wild; from Clint Eastwood, Pale Rider and Bird; from Paul Schrader, American Gigolo, Cat People, Mishima, and the Bressonian Patty Hearst. Coppola, supposedly a marked man after Apocalypse Now, gave us another anti-musical (One from the Heart) and a robust biopic (Tucker: The Man and His Dream). De Palma outraged his audience with Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, and Scarface. John Carpenter’s B-movie sensibility was given full throttle in Escape from New York, The Thing, and Big Trouble in Little China. And arguably David Cronenberg hit his stride with Scanners, Videodrome, The Dead Zone, The Fly, and Dead Ringers. Maybe we should just call the 80’s the Cronenberg Years.

Veteran directors also got in their licks. Sidney Lumet had a remarkable run; if you bet on Serpico, I see you The Verdict and raise you Prince of the City. Sergio Leone offered Once Upon a Time in America, a film that looks more ambitious on each viewing. John Huston checked in with Prizzi’s Honor and The Dead, Sam Fuller with The Big Red One.

Biskind castigates the 1980s for parvenu producers like Don Simpson and Michael Eisner, but he doesn’t mention all the new directors who emerged. Some allied themselves with independent companies or mini-majors, others worked through the studios, but in any case it’s strange to overlook Michael Mann, Oliver Stone, Tim Burton, the Coens, Spike Lee, Robert Zemeckis, James Cameron, George Miller, Barry Levinson, John Sayles, Gus Van Sant, Jim Jarmusch, Katherine Bigelow, David Mamet, Steven Soderbergh, et al. Just cherry-picking their films yields up Thief, Manhunter, Salvador, Platoon, Wall Street, Born on the Fourth of July, Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, Beetlejuice, Batman, Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, She’s Gotta Have It, School Daze, Do The Right Thing, Used Cars, Diner, Tin Men, The Abyss, Return of the Secaucus Seven, Matewan, Mala Noche, Drugstore Cowboy, Stranger than Paradise, Down by Law, Mystery Train, Near Dark, House of Games, Things Change, sex, lies and videotape. Not many dribs of feel-good pap in this bunch.

There was a lot of bloated Oscar bait, I grant you. Is anybody, anywhere on the globe watching Gandhi or Chariots of Fire or Driving Miss Daisy at the moment? But we had Amadeus, an intelligent biopic, as well as Tender Mercies and Coal Miner’s Daughter and Rain Man.

The 1980s kept genres firmly at the center of Hollywood. Instead of working against genre conventions, as many Movie Brats had done (not all; remember Bogdanovich), many of the most talented Eighties directors found ways to do what they wanted in and through genres. In this sense, they were more like Hawks and Ford and other classical filmmakers. The “personal” mainstream film wasn’t a contradiction in terms.

Take science fiction. Blade Runner, which became as influential as Metropolis and 2001, pushed to an extreme the premise of Alien: The future will be rusty, drippy, and stygian. Blade Runner also expanded teenage vocabularies by at least one word (can you say dystopian?). Handed another cult science-fiction story, David Lynch turned Dune into a pageant of hallucinatory grotesques. Voices float unbidden in the air, and boils never looked so glistening. Today, these overstuffed genre pieces repay viewing more than Out of Africa does.

Granted, the 80s gave us plenty of earnest clunkers in the drama department, perhaps most notably The Color Purple. But we also have Body Heat, Never Cry Wolf, Fatal Attraction, Witness, Kiss of the Spider Woman, The Accused, Terms of Endearment, The Right Stuff, Field of Dreams, River’s Edge, Places in the Heart, The Big Chill, and other sturdy efforts.

If you admire Ishtar, then add it to this list. Ditto the parboiled stylings of Alan Parker: Pink Floyd The Wall, Birdy, Angel Heart, and Mississippi Burning. And if you grew up on John Hughes movies, there’s no more to be said by me. You probably still love Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, and the rest. Okay, maybe we should consider it the Hughes decade.

Laughs and bullets

Fantasy comedy flourished in the period, from a masterpiece of dark humor like Beetlejuice to amiable fare like Ghostbusters, Big, Splash, and All of Me. Add to this list Gremlins, sort of the down-and-dirty E. T.; I dare you to watch this or the 1990 sequel without laughing. Farce was also on the agenda, with the output of Mel Brooks (Spaceballs) and the Zucker-Abrams team (Airplane! Top Secret!), and one-offs like A Fish Called Wanda. Saturday Night Live continued to breed new stars. Bill Murray, today an axiom of the independent cinema, made his debut in the period. And after The Adventures of Pluto Nash (2002) and Meet Dave (2008), it’s heartening to remember Eddie Murphy’s appeal in 48 HRS, Beverly Hills Cop, Trading Places, and Coming to America.

On the romantic comedy front, we had Victor/ Victoria, Mystic Pizza, Desperately Seeking Susan, Broadcast News, Moonstruck, Bull Durham, and one of the supreme achievements in the genre, Tootsie. I never met anybody who didn’t like Tootsie.

Speaking of romantic comedy, every era has its favorite perky blonde. Long ago it was Doris Day; today it’s Reese Witherspoon. In between came Goldie Hawn, who gave us Private Benjamin and, mixing it up with Chevy Chase, two trim comedies Foul Play (okay, 1978) and my own favorite, Seems Like Old Times, a frothy revival of the screwball tradition. Her mantle was picked up by Meg Ryan in When Harry Met Sally, and she continued to deliver pert-and-lovable through the 1990s.

Movies centering on kids, like WarGames and The Karate Kid and Stand by Me, proved unexpectedly enjoyable to grownups too. Back to the Future was an intricate Oedipal fable, coarsened but also complicated in the second installment and sweetened in the third. Coppola’s flirtation with teenage art movies gave us The Outsiders and Rumble Fish. Fame is probably a part of every Gen-Xer’s childhood too, as are other musicals like Flashdance, Dirty Dancing, Hairspray, and the 1989 resurrection of Disney animation, The Little Mermaid.

With the new attractiveness of the global market, the demands of home video, and increasingly sophisticated special effects, the 1980s brought the really violent action movie into its own. I’m not ready to defend Rambo and its clones, not even the indifferently directed Lethal Weapon. But I will stick up for Fort Apache—The Bronx, The Terminator, Robocop, Aliens, Predator, and The Untouchables, the last of which has given us many lines appropriate to President-elect Obama’s Chicago-based campaign. (“Brings a knife to a gunfight.” “They send one of yours to the hospital, you send one of theirs to the morgue.”) Road Warrior probably counts as an import, but we ought to treat Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome as a Hollywood release. This sequel transposes the earlier film’s grimly amusing chases and stunts into full-out slapstick, while giving us one of the most touching finales of any film of its day.

I save for last the obligatory mention of Die Hard, the Jaws of the 1980s: a perfectly engineered entertainment.

Middlebrow, semi-highbrow

I don’t automatically despise middlebrow culture (a subject, I hope, for a future blog). But many cinephiles do, so I’m probably in the minority in my esteem for another prototypical 80s director, Ron Howard. Like Zemeckis, he started his climb with a something a little naughty, the mortuary comedy Night Shift. Thereafter he tried to update Hollywood genres in ingeniously middlebrow fashion, from Cocoon and Gung Ho to Parenthood, probably his best film of the decade.

Hollywood films have long blended art-cinema experimentation and genre conventions; it’s what a lot of people found exciting about The Conversation and The Godfather Part II and the seventies work of Altman. That sort of blending continued in the 1980s. The most obvious examples came from David Lynch, with The Elephant Man (surreal visions plus disfigured hero) and Blue Velvet (the Hardy Boys meet sadomasochism). Another merger of art movie and genre movie was The Stunt Man, a three-card-monte affair about moviemaking. Want a postmodern musical? David Byrne’s True Stories treated avant-garde art as of a piece with down-home kitsch. The music track is infectious, with the lip-sync sequence on “Wild, Wild Life” capturing the sense that everyone can be famous for, well, not fifteen minutes but about ten seconds.

I’m venturing onto disputed terrain here, but I vote for Alan Rudolph’s Choose Me as an intelligent blend of Euroart neuroticism and off-kilter romantic comedy. The first shot, a long take craning down the side of a bar sign and along a street filled with hustlers sometimes dancing and sometimes not, accompanied by Teddy Pendergrass’s music, remains a tingling moment of bravado. The interruptive flashbacks (or are they visions?) and some tricky pan shots play daringly with character motivations. I also admire Trouble in Mind and The Moderns, but I realize that making a case for them would probably be pushing my luck.

When was the last time Woody Allen made a really good movie? Hard to say, but recall three 1980s titles: Hannah and Her Sisters, Zelig, and Crimes and Misdemeanors. They show that Allen could take chances with adventurous narrative strategies, while mixing in mordant dialogue, social satire, surprisingly bitter comedy, and earned pathos. Consider Radio Days the cherry on top.

There are plenty of other worthwhile items: My Favorite Year, The Dream Team, Valley Girl, Adventures in Babysitting, Excalibur, Earth Girls Are Easy, The Abyss, This Is Spinal Tap, D. C. Cab, The Princess Bride, Total Recall, Day of the Dead, Monkey Shines, Streets of Fire, Housekeeping, Purple Rain, Koyaanisqatsi, The Thin Blue Line, and on and on. Few are perfect, but most offer genuine pleasures, and some are as imaginative and bold as the canonized films of the 1970s, albeit in different registers.

Not every film on my list will convince everybody, but I think there are enough solid achievements to show that the blockbuster era didn’t suffocate creative filmmaking in the U.S. In some cases it enhanced it.

Come to think of it, the American cinema always renews itself. Take the 90s. There’s My Cousin Vinny and . . . .

(1) Biskind, Easy Riders and Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock’n’Roll Generation Saved Hollywood (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998), 438.

(2) Biskind, Easy Riders, 404.

(3) Tom Shone, Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer (New York: Free Press, 2004), 11. Shone’s book is the best antidote I’ve found to the overreaching attacks on 1980s cinema. For a dauntingly comprehensive filmography, see Robert A. Nowlan and Gwendolyn Wright Nowlan, The Films of the Eighties (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1991).

One from the Heart.

Gradation of emphasis, starring Glenn Ford

DB here:

Charles Barr’s 1963 essay “CinemaScope: Before and After” has become a classic of English-language film criticism. (1) It proffers a lot of intriguing ideas about widescreen film, but one idea that Barr floated has more general relevance. I’ve found it a useful critical tool, and maybe you will too.

Grading on a curve

Barr called the idea gradation of emphasis. Here’s what he says:

The advantage of Scope [the 2.35:1 ratio] over even the wide screen of Hatari! [shot in 1.85:1] is that it enables complex scenes to be covered even more naturally: detail can be integrated, and therefore perceived, in a still more realistic way. If I had to sum up its implications I would say that it gives a greater range for gradation of emphasis. . . The 1:1.33 screen is too much of an abstraction, compared with the way we normally see things, to admit easily the detail which can only be really effective if it is perceived qua casual detail.

The locus classicus exemplifying this idea comes in River of No Return (1954). When Kay is lifted off the raft, she loses her grip on her wickerwork bag and it’s carried off by the current. (See the frame surmounting this entry.) Kay and her boyfriend Harry are rescued by the farmer Matt. As all three talk in the foreground, the camera catches the bundle drifting off to the right.

Even when the men turn to walk to the cabin, Preminger gives us a chance to see the bundle still drifting downstream, centered in the frame.

The point of this shot, Barr and V. F. Perkins argued, is thematic. As Kay moves from the mining camp to the wilderness, she will lose more and more of her dance-hall trappings and be ready to accept a new life with Matt and Mark. The last shot of the film shows her final traces of her old life cast away.

Cutting in to Kay’s floating bag would have been heavy-handed; if you stress a secondary element too much, it becomes primary. Barr reminds us that any film shot can include the most important information, as well as information of lesser significance. A film can achieve subtle effects by incorporating details in ways that make them subordinate as details and yet noticeable to the viewer. Or at least the alert viewer.

In Poetics of Cinema, I wrote an essay on staging options in early CinemaScope, and Barr’s idea helped me illuminate some of the strategies I discuss. (For earlier comments on Barr on Scope and River of No Return, see my article elsewhere on this site.) Today I want to consider how the notion of gradation of emphasis has a more general usefulness.

Barr contrasts the open, fluid possibilities of CinemaScope with two other stylistic approaches, both found in the squarer 1.33 format. The first approach is the editing-driven one he finds in silent film. This tends to make each shot into a single “word,” and meaning arises only when shots are assembled. Barr associates this approach with Griffith and Eisenstein. The second approach, only alluded to, is that of depth staging and deep-focus shooting, typically associated with sound cinema of the late 1930s and into the 1950s.

Both of these approaches, montage and single-take depth, lack the subtle simplicity of Scope’s gradation of emphasis.

There are innumerable applications of this [technique] (the whole question of significant imagery is affected by it): one quite common one is the scene where two people talk, and a third watches, or just appears in the background unobtrusively—he might be a person who is relevant to the others in some way, or who is affected by what they say, and it is useful for us to be “reminded” of his presence. The simple cutaway shot coarsens the effect by being too obvious a directorial aside (Look who’s watching) and on the smaller [1.33] screen it’s difficult to play off foreground and background within the frame: the detail tends to look too obviously planted. The frame is so closed-in that any detail which is placed there must be deliberate—at some level we both feel this and know it intellectually.

To see Barr’s point, consider a shot like this one from Framed (1947).

The shot, rather typical of 1940s depth staging, displays an almost fussy precision about fitting foreground and background together. That bartender, for instance, stands squeezed into just the right spot. (2) Barr claims that we sense a certain contrivance when primary and secondary centers of interest are jammed into the 1.33 frame like this.

We don’t sense the same contrivance in the widescreen format, he suggests. Barr assumes, I think, that the sheer breadth of any Scope frame will include areas of little consequence, whereas that’s comparatively rare in a 1.33 composition. This is an intriguing hunch, but uninformative patches of the frame may not be intrinsic to the Scope technology. Perhaps the fairly neutral and inexpressive uses of Scope that dominate the early 1950s, the sense of empty and insignificant acreage stretching out on all sides, make us expect that little of importance will be found there. Accordingly, directors can create a sense of discovery when we spot a significant detail in this stretch of real estate.

Anyhow, Barr indicates that if static deep-space staging made the frame too constrained, 1930s and 1940s directors who combined depth with camera movement created more spacious and fluid framings. He suggests that Mizoguchi, Renoir, and others anticipated the possibilities of Scope.

Greater flexibility was achieved long before Scope by certain directors using depth of focus and the moving camera (one of whose main advantages, as Dai Vaughan pointed out in Definition 1, is that it allows points to be made literally “in passing”). Scope as always does not create a new method, it encourages, and refines, an old one (pp. 18-19).

Barr believes that Scope positively encouraged gradation of emphasis, and that widescreen directors of the 1950s and 1960s have made the most fruitful use of the strategy. But he allows directors of all periods utilized gradation of emphasis, even in the standard 1.33 format. This is, I believe, a powerful idea.

Before Scope: Making the grade

Barr’s discussion of silent cinema, relying on notions of editing associated with Griffith and Soviet directors like Eisenstein, is done with a broad brush, but it’s typical of the period in which he was writing. We didn’t know much about silent filmmaking until archivists started to exhume important work in the 1970s. It’s no exaggeration to say that we haven’t really begun to understand the first twenty-five years of cinema until fairly recently.

In a way, the staging-driven tradition of the 1910s, which I’ve often mentioned on this site (here and here and here), exemplifies some things that Barr would approve of. Directors of that period made extraordinary use of the frame and compositional patterning. They staged action laterally, in depth, or both. They let shots ripen slowly or burst with new information. This approach to using the full frame (with only occasionally cut-in elements) has come to be called the tableau style, emphasizing its similarity to composition of a painting—although we shouldn’t forget that these films are moving paintings, and the compositions are constantly changing. The result is that emphasis tends to be modulated and distributed among several points of interest.

Central to this strategy, I think, was camera distance. American directors tended to set the camera moderately close, cutting figures off at the knees or hips, and by taking up more frame space, the foreground actors tended to limit the area available for depth arrangement or for significant detail.

This shot from Thanhouser’s The Cry of the Children (1912) is a rough 1910s equivalent of the crammed shot from Framed above. (See also the tightly composed shots from DeMille’s Kindling (1915) here.)

The European directors, by contrast, tended to let the scene play out in more distant shots, creating spacious framings of a sort that would be reinstituted in early CinemaScope. Consider this shot from Holger-Madsen’s Towards the Light (Mod Lyset, 1919) and another from Island in the Sun (1957).

Both, it seems to me, have the type of open composition and the foreground/ background interplay that Barr praises in his article.

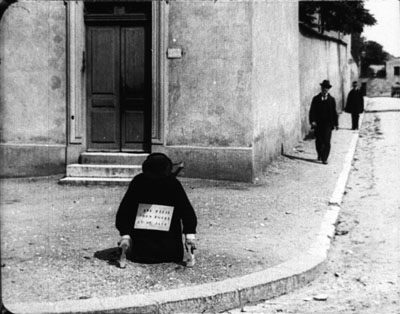

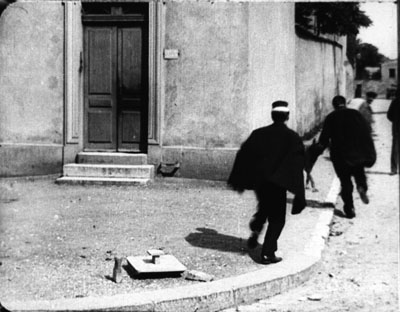

We can go back further. The Lumière brothers’ cameramen made fiction films as well as documentaries, and we occasionally find moments that suggest early efforts at gradation of emphasis. In Le Faux cul-de-jatte (1897), an apparent amputee is begging in the foreground while in the distance a man is walking down the street.

A cop crosses the street from off right and follows the pedestrian.

As the foreground fills up, the man we’ve seen in the distance gives the beggar some money.

As he goes out left, the cop is still approaching, and a vagrant dog appears.

The cop comes to the beggar, partially blocking the dog, who takes care of other business. (Not everything in this movie is staged.)

The cop checks the beggar’s papers and finds them to be suspect. The fake amputee jumps up and races off in the distance, with the cop pursuing.

As with many staged Lumière shorts, several figures converge in the foreground in order to create a culminating piece of action. Here the distant man and the cop, both secondary centers of interest, serve as a kind of timer, assuring us that something will happen when they meet at the beggar.

These are just some quick examples. We should continue to study the ways in which, with minimal use of editing, early filmmakers found ingenious ways to create gradation of emphasis. (2)

Some uses of grading

Barr, like most critics writing for the British journal Movie, was sensitive to the ways in which technique has implications for character psychology and broader thematic meanings. Kay’s bundle is one point along a series of changes in her character and her situation. But gradation of emphasis can serve more straightforward narrative purposes as well.

Consider our old friends, surprise and suspense. In the original 3:10 to Yuma (1957) Dan Evans is confronting the ruthless outlaw Ben Wade.

We get a string of reverse shots.

Then in one shot of Wade, without warning, a shadowy figure emerges out of focus in the left background.

Now we realize that Evans has been diverting Wade from the fact that the sheriff’s posse is surrounding him. Now we wait for Wade to discover it; how will he react?

While we’re on Glenn Ford, another nice example occurs in Framed. Mike Lambert has been romancing a woman named Paula, but we know that she and her lover Steve are plotting to fake Steve’s death and substitute Mike’s body.

She brings Mike to Steve’s elegant country house, having presented Steve as someone she knows only slightly. When Mike goes into the bathroom to wash up, we notice something important behind him.

With Mike at the sink, we have plenty of time to recognize Paula’s robe. Director Richard Wallace prolongs the suspense by giving us a new shot of Mike in the mirror, with the robe no longer visible.

But when Mike turns to leave, a pan following him brings him face to face with what we saw, accentuated by a track forward.

We get Mike’s reaction shot, followed by a cut to Steve and Paula downstairs, suspecting nothing. “So far, so good,” says Steve, looking upward at the bathroom.

The rest of the scene will play out with Mike aware that they’re deceiving him. As often happens with suspense, we know more than any one character: We know the couple’s scheme and Mike doesn’t, but they don’t (yet) know that Mike is now on his guard.

This isn’t as subtle a case as River of No Return, but I suspect that it’s more typical of the way Hollywood filmmakers use gradation of emphasis. Paula’s bathrobe is a good example of what I called in The Classical Hollywood Cinema the strategy of priming: planting a subsidiary element in the frame that will take on a major role, even if initially its presence isn’t registered strongly. My example in CHC was a coat rack in the Dean Martin/ Jerry Lewis comedy The Caddy (1953). In effect, the distant pedestrian in the Lumière film is an early example of priming.

Howard Hawks adopts the Lumière technique in order to sustain a flow of dialogue in Twentieth Century (1934). Here the foreground conversation is accompanied by a procession of people emerging in the distance and stepping up to take part.

The shot concludes, as does the shot of Faux cul-de-jattes, with a retreat from the camera.

The priming of secondary elements here, the summoning of the train attendant and the conductor, obeys Alexander Mackendrick’s dictum that the director ought to construct each shot so as to prepare for what will come next.

As Barr indicates, the idea of gradation shades insensibly off into general matters of cinematic expression. In The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947), the bank robber has hitched a ride with an unassuming civilian, and they stop for gas. When the attendant shows a picture of his little girl, the robber gratuitously insults her. (“With those ears she’ll probably fly before she can walk.”)

Later, the station attendant hears a radio broadcast describing the fugitive. First he has his head cocked as he listens attentively, but then his gaze drifts to the picture of his little girl.

The attendant is the center of dramatic interest, but when he looks at the picture, so do we (primed by the view of it earlier). Instantly we understand that the attendant’s resolve to call the police springs partly from an urge to get even with the man who insulted his daughter. A minor instance, surely, but it illustrates Barr’s point that the notion of gradation of emphasis leads us to consider “the whole question of significant imagery.”

The more the merrier

Barr seems to favor a plain style; he prefers Preminger’s quiet framings to the rococo imagery of Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954). Presumably the famous shot above from Wyler’s Best Years of Our Lives (1946) would be too obviously composed for Barr’s taste.

But there is merit in considering how a secondary center of interest can vie for supremacy. André Bazin declared Wyler’s shot a bold stroke exactly because its self-conscious precision created a tension between what was primary and what was subordinate. (3) The action in the foreground is of dramatic interest because Homer has learned to play the piano, and this represents a phase of his coming to terms with his wartime disability. Yet the most consequential action is taking place in the distant phone booth, where Fred breaks up with Al’s daughter Peggy. The gradation of emphasis is inverted, and we wait in suspense to find out what happens. Bazin taught us to recognize that what appears to be primary may actually be creatively distracting us from the scene’s principal action. (4)

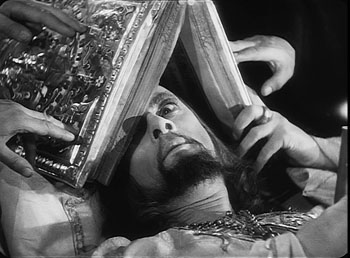

A director can also turn a primary center of interest into something secondary, but powerful. In one sequence of Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible I (1944), the apparently dying tsar is being prayed over by churchmen. Ever suspicious, he peers out from under the book, using only one eye.

As the scene develops, Prince Kurbsky meets Ivan’s wife and tries to seduce her. In the background an icon’s eye glares out, as if Ivan is watching them.

The single eye, which is a motif we find in other Eisenstein films, becomes a significant one throughout both parts of Ivan. More generally, this device manifests Eisenstein’s conception of polyphonic montage, which explored how the filmmaker can control all the various aspects of his images and make them weave throughout the film—promoting one at one moment, demoting it at another. (5)

Barr’s essay assumes that Eisenstein’s montage stripped each image down to a single meaning. In fact, though, Eisenstein wanted to multiply the sensuous and intellectual implications of each shot by weaving objects, gestures, body parts, musical motifs, and the like into an ongoing stylistic fabric. Each shot’s gradation of emphasis can suggest thematic parallels, deepen the drama, or heighten emotional expression, just as a complex score enhances an operatic scene.

Tati as well likes to create an interplay between primary and subsidiary centers of interest. Or rather, he sometimes abolishes our sense of what is primary and what isn’t. The crowded compositions of Play Time (1967) often bury their gags in a welter of inessential details. During the lengthy scene in the Royal Garden restaurant, a minor running gag involves the dyspeptic manager. He has just mixed some headache medicine with mineral water, but the action is easily lost within the tumultuous image. Even the soundtrack cues us only slightly, with a bit of fizz among the music and crowd noise.

As the manager lowers the glass, Hulot thinks it’s pink champagne being offered to him.

Rolling the stuff in his mouth, Hulot realizes his mistake as he earns a stare from the manager.

There is so much competing sound and activity in the shot that some viewers simply don’t notice this bit at all. In Play Time, gradation of emphasis is often flattened out, leaving us to rummage around the composition for the gag.

Some final notes

Barr was not particularly interested in the mechanics of how we come to notice something in the shot, be it primary or secondary in value. In On the History of Film Style, I suggested that many aspects of technique work to call attention to any element in the field. The filmmaker can put a something in motion, turn it to face us, light it more brightly, make it a vivid color, center it in the frame, have it advance to the foreground, have other characters look at it, and so on. These tactics can work together in a complex choreography. In Figures Traced in Light, I argued that they depend on the fact that we scan the frame actively; the techniques guide our visual exploration. (6)

You can see this guidance at work in most of the examples I’ve mentioned. In River of No Return, we are coaxed into noticing Kay’s bundle because we’re cued by movement (the bundle falls and drifts off), performance (she shouts, “My Things!” and stretches out her arm), music (we hear a chord as the bundle splashes), and framing (Preminger’s camera pans slightly as the trunk drifts away). The critic can refine our sense of the effects that a film arouses, but it’s one task of a poetics of cinema, as I conceive it, to examine the principles and processes that filmmakers activate in achieving those effects.

Finally, we might ask: To what extent do we find gradation of emphasis in current filmmaking? Today’s American cinema relies heavily on editing, using a style I’ve called intensified continuity. Each shot tends to mean just one thing, and once we get it we’re rushed on to the next. The unforced openness of the wide frame that Barr celebrated has been largely banned, in favor of tight singles—even in the 2.40 anamorphic format. It seems that most filmmakers are no longer concerned with gradation of emphasis within their shots.

To find this strategy surviving at its richest, I think we have to look overseas. If you want names: Angelopoulos, Tarr, Kore-eda, Jia, Hou. (7)

(1) It was published in Film Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4 (Summer, 1963), 4-24. Unfortunately, it’s not available free online, nor is a complete version available in anthologies, so far as I know. If you have access to online journal databases, you can find it. Otherwise, off to the library w’ye!

(2) In the Poetics of Cinema piece (pp. 303-307), I argue that some early uses of Scope tried to approximate such tightly organized composition, despite technological barriers to focusing several planes of action.

(3) See André Bazin, “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo, trans. Cardullo and Alain Piette (New York: Routledge, 1997), 14-16.

(4) Actually the phone booth is primed for our notice by earlier shots in Butch’s tavern. See On the History of Film Style, 225-228.

(5) For more on Eisenstein’s idea of polyphonic montage, see my Cinema of Eisenstein (New York: Routledge, 2005) and Kristin’s Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

(6) For some empirical evidence of this guided scanning, see the work of Tim Smith at his website and in this entry on this site.

(7) I discuss some of these alternatives in On the History of Film Style and the last chapter of Figures Traced in Light.

Eternity and a Day.

PS 15 Nov. Two more items. First, if the ideas floated here intrigue you, you might want to take a look at an earlier entry on this site, called “Sleeves.”

Second, I had planned to include one more example, but forgot it. In Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Andy Hanson’s life is unraveling. We follow him back to his apartment, and as he enters on the extreme left, his wife Gina is visible sitting on the extreme right, her back to us.

Gina forms a secondary center of attention, but the key to the upcoming action is revealed in a third point of interest: the black suitcase pressed against the right frame edge. The shot tells us, more obliquely than one showing her leaving the bedroom with the case, that she is planning to leave him. Lumet’s image, reminiscent of the framing of the trunk in River of No Return, shows that gradation of emphasis isn’t completely dead in American cinema. The orange scrap of yarn, knotted to the handle for baggage identification, is a nice touch of realism as well as a welcome color accent that further draws the suitcase to our notice.

Filling the New Line gap

The Loews Santa Monica Beach Hotel, one of the AFM venues

Kristin here-

The 2008 American Film Market started yesterday. Like the film festivals at Cannes, Toronto, and, increasingly, Berlin, the AFM is one of the major places where independent and foreign-language films get sold. Distributors from all over the world come to sell their products and to buy the films that they will release at home. It seems a good occasion to look at what effect the folding-in of New Line Cinema into a unit within Warner Bros. early this year has had on the international independent film market.

The good old days

In my book The Frodo Franchise, Chapter 9 dealt with the impact of The Lord of the Rings on the film industry. There I discuss what effects the trilogy had on New Line and its parent company Time Warner. I also analyze the rise of the fantasy genre, the technological advances, and the boost given to the depressed indie market internationally. The 26 international independent distributors that financed a substantial portion of the film’s production through presales—with commitments to all three parts, sight unseen, at very steep prices—grew dramatically as a result of its success.

In 2001, an international slump in independent and foreign-language cinema started. The causes were complex, and I detail them in the book; they included a sag in advertising, the dot-com bust, the September 11 attacks, and the American dollar’s high exchange rate. With perfect timing, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring came out in December of 2001. Its theatrical and DVD earnings in 2002 poured money into the market through the 26 companies’ ability to buy new product when other distributors were still strapped for cash. By early 2004, the market had substantially recovered. Rings wasn’t the only factor aiding that recovery, but it was a major one.

That section of Chapter 9 is one of the parts of the book I’m proudest of. Most people interested in film knew something about most of the topics I covered. They were probably at least vaguely aware of the video games and other tie-in products, the highest successful internet campaign, the growth in filmmaking and tourism in New Zealand, and so on. But the fact that this massive blockbuster was an independently financed film, sold on the independent market, and highly beneficial to that market was something completely unknown except to specialists within the industry. I cottoned onto it only because there were a few references to these distributors’ unusual buying power during the coverage of the 2003 Cannes Film Festival and AFM in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter.

Beyond those brief discussions, there was really no way I could research the topic without talking to people involved. That meant interviewing some of the executives of those 26 companies and someone very expert in the international indie market. A very helpful source was Mads Nedergaard, then of SF-Film, Copenhagen, who provided marvelous information for my major case study in that chapter. For the expert, I decided upon Jonathan Wolf, then and now the Managing Director of the AFM. Luckily he agreed to be interviewed. During our conversation Jonathan remarked that he had been very struck that I understood that Rings was an independent film and that it had had a positive impact on international markets. I gather that’s why he agreed to the interview, during which he furnished me with valuable insights. Those two interviews really made that part of the chapter possible.

Despite the huge success of the trilogy, New Line continued to function as an independent, financing its films through presales of distribution rights and of licensing fees for ancillary products. It continued to sell them at events like the AFM, as well as having regular output deals with some of the same overseas companies that it had been dealing with for nearly a decade. New Line was one of the main U.S. firms supplying such distributors. Its growing success ultimately became part of what got the studio into trouble.

What had worked so well for Rings continued to work until the blockbuster fantasy trilogy that had been touted as the successor to Rings. The Golden Compass was financed in the same way, with special rights pre-sold to foreign distributors, many of them the same ones that had handled Rings. The problem was that Compass did tepid business in the U.S. but was a distinct success abroad. That money stayed with the foreign distributors.

Absorbed into Warner Bros.

The Compass problem coincided with the promotion of Jeff Bewkes as CEO of Time Warner at a time when the conglomerate’s stock price was low. The real problem was the encumbrance of AOL, but that was a problem that would take time to solve. New Line’s lack of success with its big Christmas release made it a target. Bewkes could slash the company as a signal to stockholders that he would streamline Time Warner. On February 25, he announced that New Line would be folded into Time Warner, to become a production unit specializing in the sort of genre fare that had sustained New Line for so long, such as the Nightmare on Elm Street series. It would also continue to produce the occasional major film, such as The Hobbit.

The point of absorbing New Line into Warner Bros. was largely to downsize the former by eliminating its distribution and other departments that could be handled by Warners. With Warners distributing New Line films abroad, the income would return to the studio rather than remaining with foreign distributors. Receiving financing from Warners, New Line would no longer need to finance films through presales.

For Time Warner, this made sense, but it was a blow to the overseas distributors with regular output deals with New Line. New Line and Miramax had provided steady product to these companies, which otherwise would have to compete in the open market on a film-by-film basis. With the departure of the Weinstein brothers from Miramax, that firm had dried up as a source, leaving the burden on New Line. Now New Line was disappearing as well.

What now?

In the 7 March 2008 issue of Screen International (the online version is subscription only), Mike Goodridge discussed where these distributors might be able to turn after the expiration of their New Line contracts. He pointed out, “The distribution partners had good years and bad with New Line. None were thrilled with The Long Kiss Goodnight or The Island Of Dr. Moreau but for every flop, there was a Seven or Austin Powers, a Mask or Rush Hour.” He also confirms my claims about the Rings trilogy’s impact on its international distributors: “The success of the three films for the international partners cannot be overestimated. Nor can the fact that they, more than anybody involved, took a huge risk on the trilogy. The risk paid off. The Greens at Entertainment [the U.K. distributor], the Hadidas at Metropolitan [the French distributor] and others genuinely shared in the profits of one of the box-office phenomenons of the last 20 years. It was the international buyers’ dream. Instead of losing money on studio cast-offs, they had a hefty piece of a trilogy which grossed nearly $2bn outside North America.” New Line’s disappearance as a source of hit films “brings a dramatic sea change to the complexion of the global business,” according to Goodridge. These independent firms “will be competing for an increasingly small number of tentpole pictures available to them.”

Where have these distributors turned for films? In some cases their contracts with New Line, which predate the studio’s absorption into Warner Bros., are good through 2009. That means, however, that those distributors are already looking ahead for releases after the contracts end. At Cannes this year, New Line had a much-reduced presence. Camela Galano, one of the executives who had been in the studio’s international sales wing for years, was promoted to being its president in May. She brought only Journey to the Center of the Earth. Galano told Variety, “We just won’t be selling movies … but we’ll be doing what we normally do with our outputs, which is go through the lineup, releases and materials.”

A number of firms at Cannes stepped up to fill in the void left by New Line’s withdrawal from distribution. One up-and-coming firm, QED, was selling Oliver Stone’s W, the sci-fi film District 9 (produced by Peter Jackson and due out in the U.S. next August 14), and the Milla Jovovich thriller A Perfect Getaway. Gary Michael Walters, co-president of Bold Films, commented that he saw an opportunity presented by Warners’ takeover of New Line’s foreign distribution. “We see a sweet spot in that niche of $10 million-$30 million smart but commercial pictures.” Similar rising firms include IM Global, formed by the former head of Miramax International, Stuart Ford. (See Variety‘s summary here.)

John Hazleton analyzed the impact of New Line’s withdrawal from the international market for Screen International just before Cannes (May 9, 2008 issue). Hazleton harks back to the impact of Rings and other New Line franchises:

Many sales executives, in fact, go further and suggest that by boosting the fortunes of the distributor partners with which it had ongoing output or package deals—companies including the UK’s Entertainment, France’s Metropolitan, Australia’s Villege Roadshow and Spain’s Tri Pictures—New Line effectively elevated the independent international industry as a whole. Other sellers benefited, for example, when the New Line distributors reinvested profits from The Lord of the Rings and Rush Hour movies—or from last Christmas’ The Golden Compass—in the acquisition of non-New Line films.

No wonder, then, [that] the decision by parent Warner Bros to turn New Line into a stripped-down genre label whose films will (once current deals expire) be distributed worldwide by the studio is having such an impact in the independent arena. Filling the New Line void has suddenly become a pressing need, or an enticing opportunity, for all sorts of independent players.

One such player is Hyde Park International, whose president Lisa Wilson told Hazleton, “We’re certainly seeing an uptick in interest from distributors who previously didn’t need as much product because they were secure in having the New Line output. They’ve been making more of an effort than usual to meet us before Cannes.” Another is The Film Department, selling two films under production, Law Abiding Citizen, a thriller starring Gerard Butler, and The Rebound, a Catherine Zeta-Jones vehicle.

Hazleton identifies two major independent films suppliers that are stepping into the supply gap left by New Line’s departure:

Leading the field of remaining big picture suppliers are Summit Entertainment and the combination of Lionsgate and Mandate formed when the former acquired the latter last September. Crucially, like New Line, each group now has its own North American theatrical distribution operation, giving international buyers assurance that films will get a domestic theatrical launch and allowing the co-ordination of domestic and international release dates.

Summit is new to the domestic distribution business. But it is a company with vast international experience that plans to handle 10-12 films in the $15m-$45m budget range a year. Its Cannes slate includes Terrence Malick’s drama Tree of Life, starring Brad Pitt, and it already has output deals for its own productions in France, Germany, UK and Scandinavia.

In Lionsgate, Mandate has a well-proven domestic distribution outlet that last year scored three $50m-plus box-office hits and this year has a bigger market share than any independent or studio specialty division.

As the combination’s international arm, Mandate—which will be in Cannes with titles including Whip It! featuring rising star Ellen Page, and family animation Alpha And Omega—handles around half of Lionsgate’s domestic slate plus titles from third-party producers.

New Line’s withdrawal, says Helen Lee Kim, president of Mandate International, “just puts us in a better situation, because you can count on one hand the independent companies able to bring studio-level product to the marketplace.”