Archive for December 2008

Preserving two masters

Kristin here—

This past weekend the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Cinematheque played host to Stefan Drössler, the head of the Filmmuseum in Munich. The Filmmuseum is a major force in film restoration, and on Saturday we were treated to a much longer print of Ernst Lubitsch’s 1922 epic, Das Weib des Pharao, than had previously been available.

Lubitsch on the verge of going Hollywood

This restoration came too late for me to see it before my book on the director’s silent features, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005), was published. Not that that was a problem. I was dealing largely with style in that book, and the old version furnished plenty of examples to support my point. I argued that Das Weib was a turning point in Lubitsch’s career. It was the first film he made after the German ban on film imports was lifted and he was able to see recent Hollywood films for the first time since the war. It was also made with American financing, offering him the chance to work with American cameras and lighting equipment—an opportunity that gave him much more stylistic flexibility.

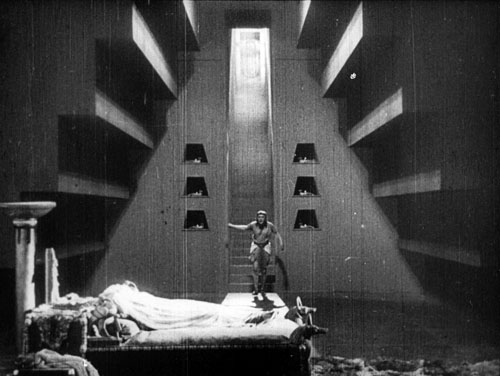

As a result, Lubitsch goes from using mostly flat, frontal light to employing the recently developed three-point lighting system. The frame above shows a very Hollywood-style lighting layout, and that’s fairly typical of this film.

Of course, it was a treat to see the film with so much new material. As I recall, the old version ran about 40 minutes, while this one is 110 minutes. There’s still footage missing, replaced in this print by still photographs and summary intertitles. Still, the plot makes a lot more sense. For the most part, the visual quality is better. The restoration depended on footage supplied by a number of archives, however, and the occasional inferior shot indicates that a less well-preserved print had to be used as source material.

The story, set in ancient Egypt, is rather clichéd and the characters little more than ciphers. The interest lies mainly in the style and the majestic scale of the production. Given a much larger budget than usual and a longer shooting schedule, Lubitsch distinctly outdid his own earlier historical dramas, Madame Dubarry (1919) and Anna Boleyn (1921). Reportedly 8000 extras participated in the battle and crowd scenes, and the sets were erected on a colossal scale. Designer Ernst Stern was a serious Egyptology buff, and despite occasional lapses, the sets, props, and hieroglyphs are a lot more authentic than those in most movies set in this era. The film’s cast also includes a remarkable line-up of some of the most prominent actors of its day: Paul Wegener, Albert Bassermann, Harry Liedtke, and Emil Jannings (above).

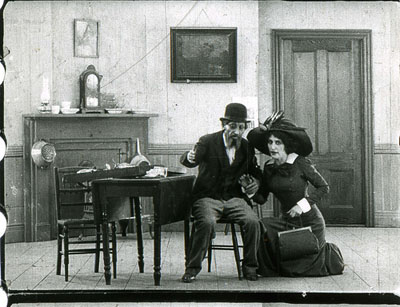

Perhaps, as happened recently with Metropolis, a new, complete version of Das Weib des Pharao will someday be found. As Stefan said, however, more footage from Lubitsch’s last German film, Die Flamme (1922) would be even more welcome. An intimate drama starring Pola Negri, it survives in only one tantalizing reel. That footage reveals the director’s rapidly growing grasp of continuity editing as well as three-point lighting. Clearly he was ready to make the move to Hollywood and to even further development as a filmmaker. (My own dream film to be rediscovered would be Kiss Me Again, a completely lost 1925 Warner Bros. feature. Odds are pretty good that the one film Lubitsch made between The Marriage Circle and Lady Windermere’s Fan would be a masterpiece.)

A new Walter Ruttmann DVD

Seeing a 35mm print of such a restoration well projected is the ideal, of course, especially with an expert pianist like the Cinematheque’s David Drazin providing the accompaniment. For those who can’t get to such screenings or who want to study its restorations, the Filmmuseum also makes many of its restorations, as well as art and avant-garde films, available on DVD.

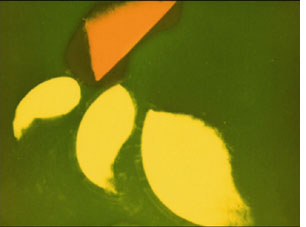

Stefan gave us a copy of one of the latest of these, a Walther (or Walter, as he sometimes spelled it) Ruttmann disc entitled “Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt & Melodie der Welt.” Actually, that’s a bit misleading, since the DVD actually contains a great deal more than those two features. All of Ruttmann’s surviving films up to 1931 are included. He was on the forefront of abstract animation, and the full series, Lichtspiel Opus I (1921), Opus II (1922), Opus III (1924), and Opus IV (1925), is included here. All have musical accompaniment, including Hanns Eisler’s 1927 score for Opus III. (That’s a frame from Opus I on the left.)

Stefan gave us a copy of one of the latest of these, a Walther (or Walter, as he sometimes spelled it) Ruttmann disc entitled “Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt & Melodie der Welt.” Actually, that’s a bit misleading, since the DVD actually contains a great deal more than those two features. All of Ruttmann’s surviving films up to 1931 are included. He was on the forefront of abstract animation, and the full series, Lichtspiel Opus I (1921), Opus II (1922), Opus III (1924), and Opus IV (1925), is included here. All have musical accompaniment, including Hanns Eisler’s 1927 score for Opus III. (That’s a frame from Opus I on the left.)

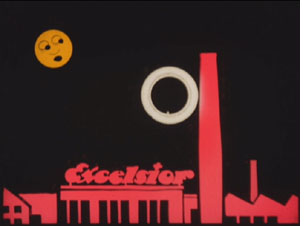

In addition, there’s a group of charming advertising films, all animated. These tend to be abstract and only bring in the product near the end. In doing the short for Excelsior tires, however, Ruttmann obviously found a round, nearly abstract shape that he could play with. A  tire rolls around in a flat landscape, having adventures that include going up and down the Excelsior factory smokestack and being threatened by spiky shapes that fail to puncture it.

tire rolls around in a flat landscape, having adventures that include going up and down the Excelsior factory smokestack and being threatened by spiky shapes that fail to puncture it.

Apart from these shorts, the two-disc set includes as bonuses a series of 22 paintings and drawings by Ruttmann, a number of texts by and about him, photographs, and so on. There’s also a CD-ROM section with additional documentation, plus a small booklet.

The two features are restorations. If you’ve only seen Berlin on a mediocre 16mm copy, this version should be a revelation. Its visual quality is gorgeous, and it has the original Edmund Meisel score, well played and well synched. The “symphony” aspect of the film makes a lot more sense with this accompaniment.

Melodie der Welt is credited with being the first German sound feature. It’s a lot simpler than Berlin. Financed  by a steamship company, it purports to follow a sailor on a huge liner around the world to exotic countries. Ruttmann takes footage from English, Greek, Japanese, and other cultures and cuts them together by topic to emphasize the similarities. Religious ceremonies are compared, military exercises intercut, children’s games assembled into a montage, people playing music (right), and so on. The laudable goal is to make customs of “exotic” peoples seem less remote and strange by showing them doing things that are not all that different from what Europeans do. A pity this was happening just before the Nazis sought to eradicate such notions of universal humanity.

by a steamship company, it purports to follow a sailor on a huge liner around the world to exotic countries. Ruttmann takes footage from English, Greek, Japanese, and other cultures and cuts them together by topic to emphasize the similarities. Religious ceremonies are compared, military exercises intercut, children’s games assembled into a montage, people playing music (right), and so on. The laudable goal is to make customs of “exotic” peoples seem less remote and strange by showing them doing things that are not all that different from what Europeans do. A pity this was happening just before the Nazis sought to eradicate such notions of universal humanity.

This set is just about ideal as a presentation of Ruttmann’s work in this period. I hope that someday a print of his 1933 fiction feature, Acciaio, will become available. It was made in Italy, and although it has been many years since I’ve seen it, I remember it as a very good film with spectacular documentary-style scenes shot in a steel mill—and as a forerunner of Neorealism.

David and I look forward to seeing Stefan at next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna and to whatever new treasures he and his fellow archivists have restored.

Fast forward, now pause

DB here:

Since Kristin got back from Petra (glimpses of her trip are here), we’ve been busy checking the page proofs of the third edition of Film History: An Introduction. It’s due out in February and we have to go over the whole enormous thing, since we’ve made adjustments to almost every chapter. There will be updates of several chapters, as well as two new chapters taking into account developments since our last edition (written in the fall of 2001). We’re also expanding our Notes and Queries supplements, which will appear online. Already our new introduction, discussing some approaches to historical research, is available elsewhere on this site.

This task hasn’t given us much time for blogging. Now, though, we are in a small hiatus before the final push, so each of us hopes to finish a blog entry this week. Kristin will write about a recent visit to Madison of Stefan Droessler, head of the Munich Film Archive. He gave lectures and screened a reconstructed Lubitsch film, The Wife of the Pharaoh (1922). My entry will focus on Wong Kar-wai’s Ashes of Time Redux. I hope to point out some interesting differences among the versions of this remarkable movie.

But to keep your eyes warm, three quick items of note.

I probably don’t have to urge you to see the new Criterion edition of Chungking Express, out in both standard and Blu-ray editions. It’s the Miramax/ Rolling Thunder version, in a crisp transfer with a nice range of color and detail. (I don’t have Blu-ray and so can’t report on that disc.) There’s also a precious 1996 British TV episode in which WKW and a beer-guzzling Chris Doyle tour some Hong Kong locales we see in the movie, tossing out technical information along the way. The show also supplies a more or less documentary record of the Midnight Express fast-food counter a couple of years after the film. Still later, the success of Wong’s film led the owner to upgrade it, with results you can see at the end of this entry.

In the supplementary short, Chris Doyle catches himself talking like a critic and says it’s because “I’ve been reading Tony Rayns.” Not by chance, the Criterion set includes a superb commentary track by Tony, who has worked closely with Wong and Doyle for years. Tony’s fluent discussion anticipates practically every question you might ask about the movie, including why Faye Wong wears a United Airlines uniform.

Chungking Express is my favorite of Wong’s work, but that’s not the main reason I devoted a chapter to it in Planet Hong Kong. I think it’s an important film historically. In the context of Hong Kong cinema, it was as much a breakthrough as was Days of Being Wild, but its offhandedness made it seem more innocuous. Wong makes daring use of plot structure: two stories, barely linked, that connect thematically rather than causally. (We also examine this aspect in one section of Film Art.) Further, Chungking Express is an exhilarating instance of a type of storytelling that fascinates me, what I call “network narrative” and that I analyze in one essay in Poetics of Cinema. Finally, because this film was more widely seen than Wong’s earlier work, it identified him with a particular style: dazzlingly composed shots alternating with smeared and rushed ones, pulsations of saturated color, precise matching of image to music, and a tone of wistful romanticism. Who else could make such an engaging movie about two guys whose girlfriends have left them?

Across his career, Wong’s technique has been more varied than the flash-and-grab breeziness of Chungking Express, Fallen Angels, and Happy Together suggests. The blurred imagery and stuttering slow motion proved easy to mimic and even parody (in Wong Jing’s Whatever You Want, 1994). In the Mood for Love and 2046 returned to the more precise and controlled staging, the nearly abstract use of setting, and the tight close-ups of Wong’s earliest films. For all their virtues, though, these late movies lack the sheer ingratiating zest of Chungking Express. If My Blueberry Nights disappointed you (as it did me), revisit the original and watch it jump off the screen. Keep an eye peeled for those reflections.

Speaking of new DVDs, today the UPS man lugged a Fox Murnau/ Borzage box to our door. This cost more than my first car (and weighs about the same), but it’s a better bargain. My oil-leaking ‘62 Impala did not come fully loaded with Sunrise and City Girl and Seventh Heaven. Dedicated Fox archivist Schawn Belston has labored hard to create this remarkable collection, as robust a contribution to our understanding of film history as his Ford at Fox box a year ago. Tucked inside the chocolate-colored case are twelve films and two handsome books with texts by Janet Bergstrom. An entire book is devoted to the lost Four Devils, and one disc houses a lengthy documentary on the two directors.

Many of the early thirties Borzages are new to me, and I can’t wait to see them. But Kristin and I are very happy to have two lesser-known titles that we love, Lucky Star (1929) and Lazybones (1925). The latter is a striking example of the trend toward the “soft style” of cinematography that swept Hollywood in the 1920s (and that Kristin analyzes in The Classical Hollywood Cinema). Even men were shot with filters, gauzes, and selective focus, creating lyrical images like the one of our hero above. The soft style was about as popular then as the dark, earth-and-steel tonalities we find in so many films today. When our travails with Film History are ended, we look forward to digging into this new Fox treasure chest.

Finally, why not try to identify a mystery movie like the one above? In an email Joe Lindner, archivist at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, writes:

The Nitrate Film Interest Group of the Association of Moving Image Archivists has put together a page on flickr where archivists can post images of unidentified films. The submissions have tended towards silent films and nitrate prints, but sound films and safety elements are welcome as well. The page is also set up for short video clips, and the first video post has just been uploaded from a new scan of a 28mm print in the Academy Film Archive’s collection. This is also a good resource for anyone out there seeking help in identifying film elements, and you do not have to be a member of AMIA to submit images.

This is a remarkable site, and the images are tantalizing. As of this writing, several films have already been identified.

So, three snacks to tide us all over. Check in later this week for some new stuff, when our eyes will focus again.

Stepping into a movie

KT here-

This past weekend I returned from a tour of ancient sites in Jordan. I didn’t plan to see any movies during the trip, but in a way it was a movie that sent me there.

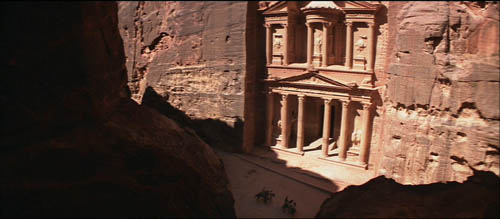

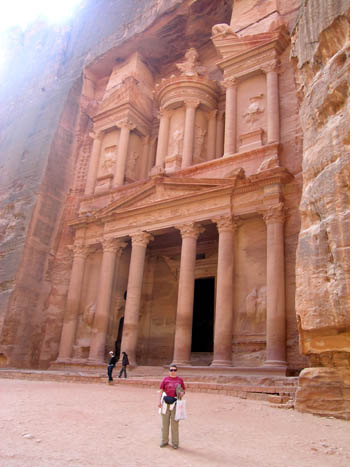

I suspect that, like me, many people first become aware of the ancient city of Petra when they watch the climactic scene of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Indie and his companions ride through a tall, narrow canyon and emerge to confront a huge red rock-cut building (above).

I suspect that, like me, many people first become aware of the ancient city of Petra when they watch the climactic scene of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Indie and his companions ride through a tall, narrow canyon and emerge to confront a huge red rock-cut building (above).

That’s not a set. It was shot at Petra in southern Jordan. The canyon is real. It’s called the Siq (“shaft” in Arabic), and it’s a dramatic crack that runs for about a mile between tall, undulating cliffs of red sandstone (on the lower layers, where most of the city’s buildings were carved) and white sandstone (on the upper layers). The other structures include a theater, temples, and many tombs.

As I learned a bit more about Petra as a real place, I conceived an ambition to visit it—not for its Indiana Jones connection but because it is such an extraordinary archaeological site. In fact, last year it was voted one of the new seven wonders of the world.

I was one of seven members of a London-based tour, plus our lecturer and local guide. There are many ancient sites in Jordan, but Petra was left until the end. What, after all, could hope to follow it and not seem a let-down?

No, I didn’t go to see movies, but I discovered it’s pretty hard to escape them. References and connections tend to pop up.

We approached the entrance to Petra through the usual rows of souvenir and refreshment stalls. Some entrepreneurs were exploiting the Indiana Jones connection. Images from posters adorned coffee shops, and more than one shop had hats on sale. They weren’t really much like the famous felt fedora, being mostly of leather and not quite the right shape.

Right beside the Indiana Jones stalls, there was the Titanic Coffee Shop. My companions were mystified as to why anyone would choose that name. To me it seemed pretty obvious. American movies are popular, and why not name your shop after the most popular of them all? There was a restaurant near our hotel called Mystic Pizza. I didn’t see any images from the film on the outside, and I didn’t go inside to find out if there were any there.

Back in early October I reported on Captain Abu Raed, reportedly the first fiction feature made in Jordan in fifty years. There doesn’t seem to be any big stigma against films, though. I saw theaters and video-rental shops, some of the latter adorned with unlicensed paintings of Mickey Mouse.

Our last stop after Petra before returning to Amman was the Wadi Rum (below), an austerely beautiful landscape of desert and small, craggy mountains. The film motif followed us. Part of Lawrence of Arabia was shot there. On the spot where the real Lawrence had trod, the real Peter O’Toole sang, “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo.”