Archive for 2008

Cavalcanti + Ealing = a little-known gem

Went the Day Well? A traitor gives information to a German infiltrator, who takes notes against a memorial to World War I dead

Kristin here—

As David and I sit here revising our Film History textbook for its third edition, we’re looking forward to the annual Il Cinema Ritrovato film festival in Bologna (June 28-July 5). We blogged from there last year and plan to do so again this year.

One of the festival’s themes in recent years has been World War II. Last year the program included Alberto Cavalcanti’s Went the Day Well?, which he directed for Ealing Studios in 1942. Partly out of a sense of duty, since I cover Great Britain for the textbook, I went to the screening. It turned out to be a well-made, engaging, and surprisingly affecting film.

Alberto De-Almeida Cavalcanti

Alberto Cavalcanti is one of those names that people who take courses in film tend to be vaguely aware of, and that for only a handful of titles. He got his start as a set designer on Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine (1923). His first film as a director, the 1926 experimental city symphony Rien que les heures, is a minor classic of the era. Coal Face (1935) is one of the better known British documentaries of the 1930s. Cavalcanti worked for Ealing for several years in the 1940s, and a modern cinema buff is likely to know his two episodes of the collectively directed Dead of Night (1945), including “The Ventriloquist’s Dummy,” the most highly regarded of the batch. Devotees of Ealing or of classic British comedy will also be familiar with his Champagne Charlie (1944). His other best-known films are Nicholas Nickleby and They Made Me a Fugitive (both 1947).

In an era of globilization, Cavalcanti’s career looks positively modern. Born in Rio De Janeiro, he made his early films in Paris. He worked in British documentaries during the 1930s before moving to Ealing, and he remained in England throughout the 1940s. The rest of Cavalcanti’s filmmaking career saw him on the move, including projects in East Germany, Israel, and Brazil. He had a brief stint in TV in the early 1970s before he retired. He died in Paris in 1982. He tended to sign his films simply “Cavalcanti,” as is the case on Went the Day Well?

British Pluck

Based on Graham Greene’s short story, “The Lieutenant Died Last,” Went the Day Well? is a “what if?” tale. A group of Germans disguised as British soldiers deceive a small village’s citizens into letting them billet there and conduct practice exercises. In reality they are there to set up observation posts in preparation for an invasion.

When the film was being planned, there were many rumors in England that a German invasion was imminent and much speculation as to whether the country could resist such a thing successfully. The film has no doubts. In fact, its brief frame story is set in 1945, and the narrator, one of the inhabitants of the fictional village Bramley End, reveals that Germany has been defeated. The narrator shows us the grave of several German soldiers who died in the attempted infiltration.

From the start, then, the spectator is aware that the apparent British soldiers who arrive in Bramley End are disguised Germans and that they will be defeated. This seems like an odd tactic, letting us know so much, and yet it makes perfect sense. The point of the early part of the film is to introduce us to the villagers who will form the collective hero of the plot. Seeing them going about helping British soldiers settle into the local hall and various households would hardly be dramatic. As it is, knowing more than they do, we are in suspense as to whether and how they will discover the truth and react.

From the start, then, the spectator is aware that the apparent British soldiers who arrive in Bramley End are disguised Germans and that they will be defeated. This seems like an odd tactic, letting us know so much, and yet it makes perfect sense. The point of the early part of the film is to introduce us to the villagers who will form the collective hero of the plot. Seeing them going about helping British soldiers settle into the local hall and various households would hardly be dramatic. As it is, knowing more than they do, we are in suspense as to whether and how they will discover the truth and react.

At first they seem the conventional characters of a comedy or light drama—the sorts who would be the supporting roles in a Hitchcock film like The Lady Vanishes. They innocently cooperate in typical British fashion, giving directions and offering tea and spare bedrooms. The initial third or so of the film is pleasant in tone, despite our underlying awareness of the enemy being let into these people’s midst.

Yet the little scenes of ordinary life swiftly and subtly set up the traits in these people that will allow them to fight back later. The local shopkeeper and telephone operator may be a bit dotty and forgetful, but she also bridles when one of  the Germans manhandles a boy who had been snooping around the equipment in the soldiers’ truck. In the same scene, that boy is established as spunky and curious. Went the Day Well? manages to set up several major characters that we come to care about, as well as many recognizable supporting figures. There is no one protagonist. In fact, the film’s top-billed actor, Leslie Banks (familiar to modern audiences mainly from The Most Dangerous Game, the original Man Who Knew Too Much, and Henry V), is a traitor, secretly aiding the Germans. That’s Banks in the photo surmounting this entry.

the Germans manhandles a boy who had been snooping around the equipment in the soldiers’ truck. In the same scene, that boy is established as spunky and curious. Went the Day Well? manages to set up several major characters that we come to care about, as well as many recognizable supporting figures. There is no one protagonist. In fact, the film’s top-billed actor, Leslie Banks (familiar to modern audiences mainly from The Most Dangerous Game, the original Man Who Knew Too Much, and Henry V), is a traitor, secretly aiding the Germans. That’s Banks in the photo surmounting this entry.

Naturally once the villagers discover who their guests really are, they come through with English pluck and resourcefulness–the women as well as the men. The film doesn’t sugar-coat the conflict, though. A number of characters one would not conventionally expect to die do meet heroic ends, and the tone rapidly turns more serious roughly halfway through the action.

Went the Day Well? is a handsome film, too. British films of the 1930s sometimes look like low-budget Hollywood imitations, but by the 1940s the studios had more resources. Cavalcanti’s design sense serves him well, and the beautifully lit scenes and crisp editing look like something MGM could have been proud of. William Walton contributes a brief but suitably grand score.

Went the Day Well? is a handsome film, too. British films of the 1930s sometimes look like low-budget Hollywood imitations, but by the 1940s the studios had more resources. Cavalcanti’s design sense serves him well, and the beautifully lit scenes and crisp editing look like something MGM could have been proud of. William Walton contributes a brief but suitably grand score.

Sources

Unfortunately Cavalcanti’s films aren’t easily available on DVD in the U.S. The only current way to buy Went the Day Well? on region 1 DVD is as part of a set, the “British War Collection.” (The set was originally released as individual discs as well, and several copies of that edition of Went the Day Well? are offered on eBay.) Amazingly, the only other in-print films are Le Capitaine Fracasse (a re-discovered 1929 French film with a young Charles Boyer, co-directed by Cavalcanti), Nicholas Nickleby, and They Made Me a Fugitive.

Those with multi-region players can visit Amazon.uk, where one can find Went the Day Well?, the three films just listed, Dead of Night, and Champagne Charlie.

Went the Day Well? seems like the kind of film ripe for a Criterion edition, if we may drop a hint in their ear.

Added May 11:

David Cairns, director and scriptwriter, critic and blogger, and Cavalcanti fan has responded to this entry with one of his own, discussing other aspects of Went the Day Well? (Beware, his entry has more SPOILERS than mine.) As he rightly points out, the early portions of the film not only set up the bucolic village and its apparently conventional British country folk, but they provide an object lesson for citizens not to behave in such a naive and unquestioning fashion. Germans might be anywhere! I was mainly writing about the narrative conventions that would hold for a modern audience watching a decades-old classic. There’s no doubt, though, that for a contemporary audience there would have been that implication. The point is fairly explicitly made when one character finally finds a clue that makes her begin to suspect something is wrong, while another dismisses her ideas–with we all the while knowing that the woman who becomes suspicious is right.

I don’t think I buy another claim David makes about a subtext for the film: “the film becomes more subversive. According to Cavalcanti, a pacifist, his objective was to show that when war comes to even a place as charming as Bramley End, the people become monsters. Without the slightest change in underlying personality, peace-loving and jocular countryfolk pick up weapons and set about slaughtering their fellow humans.”

I don’t find the villagers in any way to be monsters, even in their most violent acts against the invaders. For one thing, it’s self-defense in wartime. The starkly violent scene of the Germans ambushing and mowing down a group of men from the Home Guard makes that clear from before the point when the villagers respond. I certainly can’t believe that the audiences of 1942 would have seen the villagers as descending into some primitively violent instincts. After all, this film came out only a little over a year after the end of the Blitz. In fact, the Germans had attempted to infiltrate England in preparation for the Battle of Britain, which in turn was to culminate in a land invasion. All infiltration attempts were thwarted, and poor intelligence was a major contributing factor to what became Germany’s first significant loss of the war. There would have been few people in Britain who could conceive of pacifism as a response to what they had recently lived through.

For another thing, the villagers don’t kill ruthlessly. All three women who kill someone pause afterward, clearly upset and even nauseated . The men are more blithe about it, but they’re seldom seen killing except in pitched battles, and just as often the village menfolk are the victims up until the rescuing soldiers arrive at the end. I’d argue that the characters’ underlying personalities are assumed to include the courage and determination that surface in time of need.

Thanks to David for his thought-provoking comments and for backing me up in urging that cinephiles should seek out this and other Cavalcanti films. He mentions They Made Me a Fugitive in particular.

DVD reviewer Slarek has reviewed Went the Day Well? on DVD Outsider. (Again, SPOILERS.) Among other interesting comments, he reveals that it was shot in Turville, Oxfordshire. I think Bramley End is probably supposed to lie in the south of England, where most of the German aircraft and the putative invasion would have entered the country. Still, the rolling landscapes and hedgerow-lined fields of Kent and Sussex are fairly similar to those of Oxfordshire. As Slarek proves with a photo, the village is not all that much changed today.

Snapshots and soundbites

Boardman’s Art Theatre, two blocks from the Virginia Theatre, Champaign, Illinois.

DB here:

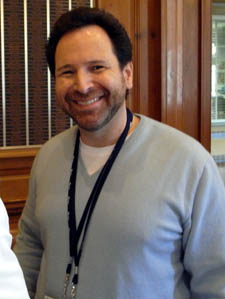

As you may surmise, a hell of a time was had by all at last week’s Ebertfest. In the sessions I moderated, I was often so busy listening and thinking about my next question that I didn’t have time to write down all the aperçus that spilled forth from the guests. But here are some soundbites, mixed with pix.

Jeff Nichols, director of Shotgun Stories: “I managed to make a 90-minute movie that feels 2 ½ hours long.”

Jeff Nichols, John Peterson (The Real Dirt on Farmer John), Eran Kolirin (The Band’s Visit), Timothy Spall (Hamlet).

Bill Forsyth on his early work: “I made films about teenagers because they were cheap to hire.”

Christine Lahti (Swing Shift, Running on Empty, Jack & Bobby, Amerika) and Bill Forsyth, reunited for the screening of Housekeeping.

Why so much multiframe imagery in Hulk? “In those notes you get from studio people,” Ang Lee explained, “they always want more and faster. So I decided to give it to them.”

Ang Lee (Hulk) and unidentified admirer.

Barry Avrich asked Suzanne Pleshette how she had survived so long in the industry. Suzanne: “I don’t have a gag reflex.”

Barry Avrich (The Last Mogul, Satisfaction, Citizen Cohl: The Untold Story, and the book Selling the Sizzle).

Paul Schrader: Theatrical screening is dead. “The multiplexes look like mortuaries.”

Tom DiCillo: “Going to a film is a religious experience. . . . When you see it on a computer screen, fuck it.”

Tom DiCillo (Delirious) and Timothy Spall.

Paul Schrader: “When I started, there was a crisis of content. Nobody knew what a movie should be about. So we had films with sex and violence and anti-heroes. But now we have a crisis of form. How long should a movie be? How big should the screen be? What is this thing called movies?”

Paul Schrader (Mishima) and Hannah Fisher (Dubai International Film Festival).

“What part of this is directing?” Tom DiCillo, reflecting on the fact that it took six years to set up Delirious and he spent only 25 days behind the camera.

Tarsem Singh: “I’ve been an atheist since I was nine. I’ve never used any intoxicant—drugs or liquor or whatever. But I don’t like to associate with nondrinkers: they’re either religious or reformed alcoholics.”

Mary Corliss (Film Comment) and Richard Corliss (Time).

Joey Pantoliano (The Matrix, Memento, The Sopranos, Canvas, and book Who’s Sorry Now) with unidentified admirer.

Michael Barker (Sony Pictures Classics).

Eiko Ishioka: “When Paul asked me what I thought about Mishima, I said, ‘I don’t like him.’ He said, ‘Perfect!'”

Eiko Ishioka (Mishima, The Cell, The Fall), multimedia artist.

The Ebertfest Team

Chaz Ebert.

Mary Susan Britt.

James Bond, projectionist, and Nate Kohn, Festival Director.

See you here next year? Jim Emerson (scanners, Rogerebert.com) is counting the hours.

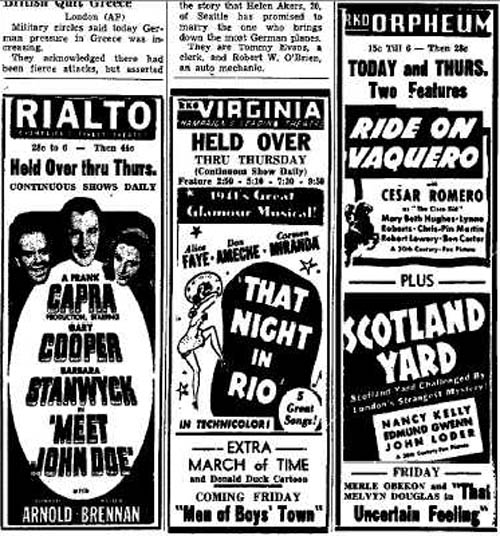

Bonus feature: What you would have been able to see in Urbana-Champaign 16 April 1941.

The show goes on

DB here:

Kristin and I had hoped to blog directly from this year’s edition of Ebertfest (formerly Roger Ebert’s Festival of Overlooked and Forgotten Films), but our blogging software failed us. We could post text but no pictures, and where’s the fun in that? Fortunately, the event was widely covered. The schedule, with very full film notes, is here. You can get a sense of what was happening by checking Jim Emerson at scanners and Peter Sobczynski at Hollywood Bitchslap and Kim Voynar at Cinematical and Lisa Rosman at A Broad View and P. L Kerpius at Scarlett Cinema and Andrew Wells at A Penny in the Well and many others. There is some coverage at the News Gazette, although the most informative stories from the paper aren’t on the net. Then there’s Roger’s own blog, Ebertfest in Exile, which in one entry goes off on an unexpected trajectory….toward Joe vs. the Volcano.

Now that we can again illustrate our entry, we offer you an ex post facto blog, like last year’s, which makes up in bulk for its tardiness. I hope to follow soon with a picture gallery.

This year’s Ebertfest lacked an essential ingredient: Roger Ebert. But Chaz Ebert took over hosting duties superbly, aided by the terrific organizational skills of Nate Kohn and Mary Susan Britt. At every screening, one person or another paid tribute to Roger’s gifts to film culture—his writing, of course, but also his tireless championing of deserving movies that should be brought to wider audiences.

The format of Ebertfest offers something for everyone. Traditionally, the opening night is an older film screened in classic 70mm, a format that’s almost vanished. Past years have included shows of Lawrence of Arabia, Play Time, and My Fair Lady. 70mm looks gorgeous on the vast screen of the Virginia Theatre. This year the film was Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet, at four hours the most complete version of the play ever put on film. It looked grand.

Another slot is reserved for a silent movie, often accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra. (Part of their armory, including bells, springs, and a thunderstrip, can be found on the left.) Having programmed The Black Pirate, The General, and The Eagle in earlier years, Roger picked von Sternberg’s sumptuous Underworld (1927), which Kristin introduced and led a discussion about. The Alloy boys’ scores are getting more nuanced by the year, and this one did as much justice to von Sternberg’s quiet passages as to the gunplay.

Another slot is reserved for a silent movie, often accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra. (Part of their armory, including bells, springs, and a thunderstrip, can be found on the left.) Having programmed The Black Pirate, The General, and The Eagle in earlier years, Roger picked von Sternberg’s sumptuous Underworld (1927), which Kristin introduced and led a discussion about. The Alloy boys’ scores are getting more nuanced by the year, and this one did as much justice to von Sternberg’s quiet passages as to the gunplay.

Yet another Ebertfest mainstay is a children’s show on Saturday morning, and last year’s wonderful Holes was followed by an unexpected pick—Ang Lee’s Hulk, with the director in attendance. The place was packed, Lee was his charming self, a trio serenaded him, and the audience left well-pleased.

Prime spots are reserved for less-known films, with an emphasis on independent and personal cinema. We saw Tom DiCillo’s Delirious, Sally Potter’s Yes, Joe Greco’s Canvas, and Jeff Nichols’ Shotgun Stories. A highlight for me was Eran Kolirin’s The Band’s Visit, which I’d missed elsewhere. This unassuming, warm, funny movie recalled Tati and 1960s Czech films like Intimate Lighting. Then there was The Cell by Tarsim Singh at a late-night screening, with John Turturro’s Romance and Cigarettes to wrap things up on Sunday. For kaleidoscopic commentary on all these, see the above-mentioned weblogs.

Princely contradictions

I hadn’t seen Hamlet in 70mm in its initial 1996-1997 run, and at first the idea of taking this fairly intimate piece to a wide-film format seemed counterintuitive. But on the Virginia screen the film lost none of the play’s intensity and it gained a welcome monumentality. The central set, the Danish throne room as a gigantic hall of mirrors flanked by a warren of corridors and fissured by secret passageways, is made for the wide image.

Scale of time also matters. By playing the full version, Branagh can give full weight to the father/ son parallels that riddle the play. If Olivier’s Hamlet was about a son’s love for his mother, Branagh makes the play about the strife between fathers and sons, with women caught in the middle. Hamlet Sr./ Hamlet Jr., Claudius/ Hamlet, Jr., Polonius/ Laertes, old Norway/ Fortinbras, and even the Player’s speech about the murder of Priam: the parallels are in Shakespeare’s text but played out at proper length they snap into sharp relief. Once Laertes is off to Paris, Polonius makes sure he’s spied on, just as Claudius orders Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern to watch Hamlet. In his turn, Hamlet assigns Horatio surveillance duty during the play-within-a-play (a piece of action nicely caught in the opera glasses that Branagh’s choice of period allows). Branagh’s decision to emphasize the military politics around Fortinbras’ march into Denmark helps justify the 70mm format and his decision to set the action in late nineteenth-century Europe; it also allows him to expand, through crosscutting set up early in the movie, the plot of another son at odds with his father.

Sex is important in this game. Branagh presents flashbacks to Hamlet and Ophelia in bed together, accentuating the prince’s later indifference and motivating her despair at his rejection. Not that the fathers don’t clock some mattress time too. Claudius the urbane politician becomes an infatuated newlywed, and Derek Jacobi gives to my mind a definitive performance. Even Polonius, usually treated as a pompous ass, smokes worldly little cigars and has a drab tucked into his bed, so that his advice to Laertes and Ophelia about proper conduct becomes not only patronizing but hypocritical.

During the Q & A, Timothy Spall and Rufus Sewall emphasized something that Branagh explains on the DVD set: the need to create ensemble performances out of footage shot at different times. Sewall (a dark and scary Fortinbras) was filmed in a few days, before full-blown production, with his bits cut into the film at intervals. Robin Williams, as Osric, was also filmed out of continuity; there are scarcely any shots of him in the same frame as other players.

During the Q & A, Timothy Spall and Rufus Sewall emphasized something that Branagh explains on the DVD set: the need to create ensemble performances out of footage shot at different times. Sewall (a dark and scary Fortinbras) was filmed in a few days, before full-blown production, with his bits cut into the film at intervals. Robin Williams, as Osric, was also filmed out of continuity; there are scarcely any shots of him in the same frame as other players.

Spall, a temporizing Rosenkrantz, was present for much more of the filming and was eloquent in explaining how shooting in long, wheeling takes demanded great precision from the actors—hitting marks, using body language, and timing speeches carefully.

Branagh put the bulky 70mm camera on a dolly, then reinforced the studio floors so that no tracks or boards were necessary; the camera could glide anywhere. “Walk and talk” technique, which I’ve blogged about before, comes home to roost in a Shakespeare film; Branagh wanted continuous shots so that the audiences could follow the flow of the speeches, and it works very well.

In fact, Branagh’s editing varies in a patterned way across the play. Acts I and III are briskly cut, averaging about 5 seconds per shot. Acts II and IV rely on much longer takes, typified by the tracking-shot arabesques, and they average 10-11 seconds per shot. And Act V? Here, as you might expect, Branagh pushes the pace to suit the converging plotlines and the burst of poisonings at the climax: the average shot runs about 3 seconds. This seesawing rhythm helps sustain viewer interest across four hours, and it shows an unusually geometrical approach to a movie’s overall architecture.

In his program review, Roger points out that the play remains deeply mysterious, even in a production as lucid and buoyant as Branagh’s. Hamlet is of course one of the most fascinatingly inconsistent characters in literature. I’ve read the play probably a dozen times and seen many film versions of it, and I’m inclined to think that in Hamlet Shakespeare is experimenting with how indeterminate a character can be and still be intelligible to us. It’s not that he’s indecisive; we have to decide what he truly is, and Shakespeare makes our task very hard.

All the other characters in the play are complicated but consistent. Only Hamlet seems to reinvent himself at every entrance. He tells us that he will put on an “antic disposition,” but before he’s gotten very far with his fake madness, he tells Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern of his strategy, knowing that they are likely to report it to Claudius. This has the effect of letting Hamlet behave any way he wants, sincere or duplicitous, calculating or mad. When he’s around others, he’s always “on,” and this makes his true nature and purposes difficult to divine.

I liked Branagh’s idea of having Hamlet consulting a book on demonology, for in a revenge tragedy the protagonist has to be sure that the aggrieved spirit urging revenge isn’t a demon in disguise. More generally, the Victorian milieu lets Branagh give us a truly bookish Hamlet, one who retreats to his stuffed library when overcome by the strife unfolding in the vast throne room. At the same time, that library contains players’ masks and a curious miniature theatre that Hamlet toys with thoughtfully. He lives among books, but also among images of pretense and deceit.

I liked Branagh’s idea of having Hamlet consulting a book on demonology, for in a revenge tragedy the protagonist has to be sure that the aggrieved spirit urging revenge isn’t a demon in disguise. More generally, the Victorian milieu lets Branagh give us a truly bookish Hamlet, one who retreats to his stuffed library when overcome by the strife unfolding in the vast throne room. At the same time, that library contains players’ masks and a curious miniature theatre that Hamlet toys with thoughtfully. He lives among books, but also among images of pretense and deceit.

The questions tease you right to the end. Hamlet finds Laertes’ plunge into Ophelia’s grave overdramatic, but he goes on to declare that he himself loved her with the strength of forty brothers. Before the climactic duel, Hamlet apologizes to Laertes (“I have shot my arrow o’er the house/ And hurt my brother”), but it seems almost bad faith, given all the misery he has helped cause. Is this a morally obtuse sincerity, or another masquerade? It’s this Hamlet, reliably unpredictable, that Branagh’s manic-depressive performance brings home so forcefully.

The unwitting wisdom of the suits

It’s common to say now that the 1970s was the last great era in American cinema, followed by the degradations of the blockbuster 80s, but that remains little more than PR. Putting aside the “revolution” of the 1970s, which seems to me overrated, I’ll just offer the opinion that the 1980s brought us many worthy films, some of them quite daring. For example, one of the sweetest “little movies” of the era is Bill Forsyth’s Local Hero (1983).

It’s a comedy, at once dry and warm, about an oil executive sent to buy a small Scottish town and beachfront in preparation for the installation of a pumping rig and refinery. Forsyth’s script reverses the cliché. The townsfolk, far from clinging to their beloved tradition, are in fact anxious to sell and look forward to being rich. The young executive, Mac, doesn’t try to drive a hard bargain but settles into the rhythm of a life different from that he has known. His boss, a passionate amateur astronomer, surprises everyone with his final decision about the deal. You might call Local Hero one of the first films about the clash of global capitalism and community values, but though that’s accurate, the schematic formula doesn’t capture the understated humor and humanity of Forsyth’s treatment.

Forsyth is at Ebertfest for a screening of his no less brilliant Housekeeping; see Jim Emerson’s eloquent and poised review here. But I wanted to ask about Local Hero. The Scottish village is rendered with the affectionate good humor we find in Ealing comedies, and Forsyth mentioned that after he’d made the film he discovered an Alexander Mackendrick movie, The Maggie (1955), that prefigured his. For me, there were echoes of Jacques Tati in the long-shots and sound gags, and Forsyth confirmed that one of the formative films in his youth was M. Hulot’s Holiday, screened by an indulgent school head.

Forsyth talked about certain choices he made. The Mark Knopfler score, bringing together Scottish tunes and a Texas twang, helped open out the film in a way that a more conventional lyrical score would not. Forsythe talked as well about the final shot, one of the most satisfying I’ve ever seen. The original cut ended with Mac returning to his Houston apartment and staring out at the dark urban landscape—beautiful in its own way, but very different from the majesty of the Scottish shore. There the original film ended, but the Warners executives, although liking the film, wanted a more upbeat ending. Couldn’t the hero go back to Scotland and find happiness, you know, like in Brigadoon? They even offered money for a reshoot to provide a happy wrapup. Forsyth didn’t want that, of course, but he had less than a day to find an ending.

Forsyth talked about certain choices he made. The Mark Knopfler score, bringing together Scottish tunes and a Texas twang, helped open out the film in a way that a more conventional lyrical score would not. Forsythe talked as well about the final shot, one of the most satisfying I’ve ever seen. The original cut ended with Mac returning to his Houston apartment and staring out at the dark urban landscape—beautiful in its own way, but very different from the majesty of the Scottish shore. There the original film ended, but the Warners executives, although liking the film, wanted a more upbeat ending. Couldn’t the hero go back to Scotland and find happiness, you know, like in Brigadoon? They even offered money for a reshoot to provide a happy wrapup. Forsyth didn’t want that, of course, but he had less than a day to find an ending.

The movie makes a running gag of the red phone booth through which Mac communicates with Houston. Forsyth remembered that he had a tail-end of a long shot of the town, with the booth standing out sharply. He had just enough footage for a fairly lengthy shot. So he decided to end the film with that image, and he simply added the sound of the phone ringing.

With this ending, the audience gets to be smart and hopeful. We realize that our displaced local hero is phoning the town he loves, and perhaps he will announce his return. This final grace note provides a lilt that the grim ending would not. Sometimes, you want to thank the suits—not for their bloody-mindedness, but for the occasions when their formulaic demands give the filmmaker a chance to rediscover fresh and felicitous possibilities in the material.

Salvation through self-punishment

Another outstanding film of the 1980s is Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), which he brought to Ebertfest in a sparkling print. Schrader is one of two American film critics who became major directors (Peter Bogdanovich is the other), and there’s little doubt that he’s the most cerebral and theoretically inclined of that group known as the Movie Brats. Even if he hadn’t written milestone screenplays (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull) and made provocative films (Blue Collar, Hard Core, Affliction), he would be remembered for his critical writing. A trailblazing essay on Joseph H. Lewis, “Notes on Film Noir,” the essay on the yakuza film, and the book Transcendental Style in Film (1972) made Schrader a distinctive voice in American film culture. Fortunately you can now read his entire oeuvre online at paulschrader.org.

While the youthful Schrader expresses admiration for Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch, he’s no cheerleader for the New Hollywood. It’s bracing to watch him tear Easy Rider and Alice’s Restaurant limb from limb. The website displays each article in situ, on its original page of print. Since he wrote for many alternative weeklies, ads for bongs and day-glo paint lie alongside Schrader’s reflections on Bresson and Boetticher.

Although I also admire Patty Hearst, Mishima is my favorite Schrader-directed project. I think it’s one of the most artistically courageous films in American cinema. Putting the dialogue almost entirely in Japanese and focusing on a writer few Americans know, it compounds its difficulty with a daunting structure. On one axis, we get four chapters: Beauty, Art, Action, Harmony of Pen and Sword. On another axis, there are three interwoven strands: an account of the final day of Mishima’s life, when he seized control of a general’s office in order to address the garrison; a chronological biography, from his childhood to his adulthood; and stylized, efflorescent scenes taken from three Mishima novels. All these strands knot in the film’s final moments, when Mishima commits seppuku in the office and we see the culmination of the action shown in the novels’ tableaus. A “cross-hatched” structure, Schrader calls it.

The three strands are kept distinct through some technical markers: black and white for the biographical scenes, cinema-verite color for the 1970 attack on the garrison, and stylized color and setting for the extracts from the novels. Schrader explained that he had originally wanted to use video for the novel scenes, but his brilliant production designer Ishioka Eiko told him that the results might not be effective. Instead, she supplied designs of a dreamy radiance.

At the same time, both the biographical scenes and the tableaux take us through different eras of Japanese history, but in a way that sharpens comparisons among them. In the 1930s the boy Mishima glimpses a female impersonator at the kabuki theatre, but in his novel of the period, Runaway Horses, the young men formulate their plan to restore the emperor through an attack on corrupting capitalists. The sets for Kyoko’s House have, Eiko explained, ugly design because in the 1950s the Japanese were copying ugly American designs (though the results look pretty ravishing onscreen).

Schrader wanted to avoid the classic plot trajectory of a hero overcoming obstacles. He sought instead to present the way that a person’s life “becomes more and more fascinating, but you never really understand it.” The shuffling of chronology let him juxtapose different aspects of Mishima’s nature. The man wasn’t exactly contradictory, Schrader says, but rather “compartmentalized”: He could keep his aesthetics, his homosexuality, his militarism, and his childhood distinct, and the film aims to show these different facets of his career.

Nevertheless, I’d argue, the film has a marked trajectory. “Perfection of the life or of the art?” Yeats asked. Schrader’s Mishima wants both, together. He seeks to fuse physicality (eroticism, violence, endurance of pain) with spirituality (given as the realm of art). The emblematic image is the poem written in a splash of blood. He finally realizes that for him this fusion can come only in death, because his life has come to embody, literally incarnate, his literary themes and techniques.

Nevertheless, I’d argue, the film has a marked trajectory. “Perfection of the life or of the art?” Yeats asked. Schrader’s Mishima wants both, together. He seeks to fuse physicality (eroticism, violence, endurance of pain) with spirituality (given as the realm of art). The emblematic image is the poem written in a splash of blood. He finally realizes that for him this fusion can come only in death, because his life has come to embody, literally incarnate, his literary themes and techniques.

Schrader’s film enacts the blending of art and life in its very imagery. At the climax, in the biographical strand Mishima climbs into a jet and the black-and-white imagery gains radiant color as he stares into the sun. The shift brings the biography up to 1970, and so provides a transition to the color footage of the writer’s last day, but it also recalls the opening credits, with the sun rising, and the closing shot of the cadet Isao about to slash himself.

Schrader regrets the transition showing Isao running to the beach, because the imagery shifts from Ishioka’s stylized world to something more realistic (albeit with glowing amber rocks). So for the upcoming Criterion DVD release he has fiddled with the final shots so that the sun and sky look far more abstract. Evidently he wants the world of art and the world of life to remain stubbornly apart—denying to his film what his protagonist yearned for.

You might object that the film’s formal intricacy and specialized themes make for a fairly chilly experience. It isn’t a wildly emotional movie, that’s true; it has some of that ceremonial, contemplative quality you get from a Philip Glass opera, which provides a theatre of pictorial attitudes rather than action. (For an example, see coverage of the current Met production of Glass’s Satyagraha.) No coincidence that Glass provided the score for the film, which he wrote without seeing any footage and which Schrader cut and shuffled to provide cues. Glass obligingly rescored the film to fit the musical collage Schrader wanted.

The film provides a visceral and a sensuous experience, but it doesn’t carry you off on waves of emotion. It will never be popular on a massive scale, because it makes almost no concessions to what people like in biopics. But if you can adjust yourself to a solemn celebration of blood and beauty, Mishima offers unparalleled rewards.

More from Schrader

“Inspiration is just another word for problem-solving.”

Schrader’s intellect never lets up. What other filmmaker could produce such a thoroughly informed academic case as he does in the 2006 “Canon Fodder” (available on his site)? One on one, I peppered him with questions and he answered with seriousness and subtlety. Two themes ran through his comments: his approach to direction and his view that cinema is dead.

On his directing: Until his last project, he embraced the “well-made film.” He shoots with a single camera, and plans his takes cut to cut. (That is, not a lot of coverage from many angles that will be winnowed out during editing.) He doesn’t storyboard because he wants to develop the staging organically on site. He visits the set, tries out blocking with the actors and DP, then decides on the spot about the breakdown into shots. For the Temple of the Golden Pavilion scenes of Mishima, like the one above, he and cinematographer John Bailey played “dueling viewfinders,” pacing around the actors to test points of view and then settling on tracking shots which incorporated the best angles.

But for his latest project, Adam Resurrected (2008), Schrader switched to a rougher style. Now, he says, he uses two cameras and he likes the bouncing and swaying frame yielded by the Bungee Cam. “I’m sick of the well-made film.”

On new media: Schrader’s stylistic turnabout comes from his conviction that cinema, “the dominant art form of the twentieth century,” is coming to an end. Today’s audience demands new forms of moving-image media. Thanks to television, young people have seen every conceivable story, so narrative is “exhausted” as an expressive resource. They expect their media products to be free, available on demand, and interactive. The result is a challenge to traditional media on every front: financial, cultural, and artistic.

Schrader looks to the Internet as not just an intriguing option but film’s destiny. So while he is planning a traditional “three-act” film, he also has written a screenplay for a 75-minute Net movie. In his essay, “Canon Fodder,” he predicted the end of traditional cinema but thought that he could keep going before the revolution. Now, he says, the sun is setting faster than he expected and if he wants to make more films he has to adjust.

I’m no prophet, but I don’t share his beliefs about the imminent collapse of traditional cinema. I also think that Web-based films, with viewers tempted to browse and graze and fast-forward, will limit aesthetic options. The computer monitor is not as hospitable to contemplative cinema, which demands that the audience patiently submit to unfolding time. When I worried at a panel that an Ozu or a Bresson could not have originated in the age of YouTube, he told me, “Get over it, David!” Though we disagree, talking with him was terrifically stimulating. I left with the hunch that Schrader will continue to devise some characteristic provocations for new media, for which we should be thankful.

Envoi

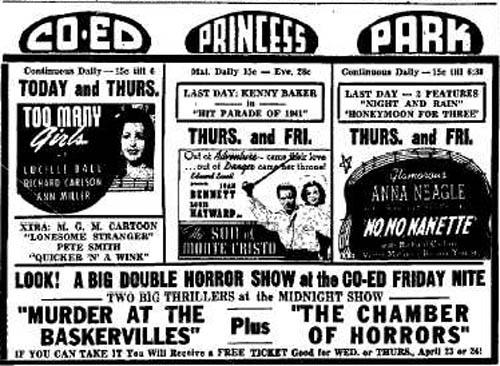

Dusty Cohl was one of the mainstays of Ebertfest, as well as the founder of the Toronto Film Festival and a shot in the arm to world film culture. He died last fall. He was honored by several events at this year’s festival, notably the biographical film, Citizen Cohl: The Untold Story, by Barry Averich (The Last Mogul). On my first visit to Ebertfest, the tough, salty guy with the quick grin and the cowboy hat immediately made me feel welcome, and he did the same when Kristin came along the following year. Everyone whose life he touched was grateful for Dusty’s generosity of mind and spirit.

Fair is still fair, and more so

Film Art: frames from Election illustrating the concept of motifs

Kristin here—

Back in 1977, when David and I began writing Film Art: An Introduction, we knew from the start that we would use frame enlargements as illustrations. At the time, that wasn’t common practice for film books, even textbooks. One reason was that it was difficult to obtain such images, but perhaps even more daunting was the notion that using frame enlargements would violate copyright. But Film Art came out of classes we had been teaching, and there we used slides of frames and 16mm clips during lectures to illustrate cinema techniques, style, and form. We didn’t see any way we could write it without photographing and reproducing actual frames.

From the start, we assumed that using frames in an educational context would be fair use. A few frames from a film would be comparable to a few words from a poem or a novel, we figured. We didn’t request permission to reproduce most of the frames printed in the book. The exceptions were films by experimental filmmakers, whom we asked more out of courtesy than because we figured we legally needed to.

One pleasant incidental result of such requests was that we now have autographs from Norman McLaren, Michael Snow, Ernie Gehr, and Bruce Connor. These unfortunately are on dull request forms. Connor livened his up a bit by adding, “I own the splices on my films. The images from individual frames are not copyrighted by myself.” He also enclosed the accompanying card as a little surrealist gesture.

One pleasant incidental result of such requests was that we now have autographs from Norman McLaren, Michael Snow, Ernie Gehr, and Bruce Connor. These unfortunately are on dull request forms. Connor livened his up a bit by adding, “I own the splices on my films. The images from individual frames are not copyrighted by myself.” He also enclosed the accompanying card as a little surrealist gesture.

We never got in trouble with the copyright holders for reproducing the hundreds of frames in Film Art. Most of our other books have also involved frames, from Méliès shorts to The Lord of the Rings.

The 1993 Report on Fair Use and Film Stills

Initially some of our editors were a bit reluctant to include those frames unless we obtained permissions from the copyright holders, but we managed to talk them into it. Then, in the early 1990s, I was asked to chair a special committee of the Society for Cinema Studies (now the Society for Cinema and Media Studies) to investigate the question of fair use of film frames and photographs. The result was the “Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Society for Cinema Studies, ‘Fair Usage Publication of Film Stills,’” written by me with help from my colleagues John Belton, Dana Polan, and Bruce F. Kawin. Experts, including the Register of Copyrights, Ralph Oman, and Prof. Peter Jaszi, an expert on copyright law, contributed their thoughts on the matter. The report first appeared in the Winter 1993 issue of Cinema Journal and is available online.

The fair-use law itself is simple. Here are the factors to be considered in determining whether the reproduction of a work violates its copyright:

1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

That last one seems to me particularly important for scholars, since it would be very difficult, if not impossible to prove that anything we publish diminishes the market value of the original. Quite the contrary, we help in our own small way to publicize that original.

I argued in the report that fair use did apply to film frames used in an educational context. The case for reproducing publicity and other behind-the-scenes photographs was considerably less clear, since unlike film frames, photographs can be individually copyrighted.

The report has had salubrious effects on film publications. Slowly more journal and academic-press editors accepted the idea that fair use does mean that authors don’t need to seek permissions. Given that most big studios either ignore such requests or demand hundreds or even thousands of dollars for their consent, the new policies of many journals and presses was a great boon to cinema studies. Gradually more and more scholarly and educational publications used frames instead of publicity stills, which made their descriptions and analysis much more effective. By now the use of film frames has become common practice.

Some encouraging cases

Occasionally, however, someone who is nervous about using frames writes to me to ask if anything has happened since 1993 that would change the situation. Has anyone been sued by a film studio for using film frames? Has a precedent been set?

In the report, I predicted that no studio would ever sue over the academic use of film frames. That was partly because the studios have bigger fish to fry, particularly the huge question of how to prevent film piracy. In contrast to bootleg DVDs selling for a couple of dollars in the streets of Shanghai or Moscow, we film scholars do not figure in the consciousness of the studio legal departments.

There have been some events that I think make it worth revisiting the issue of fair use in a more informal way here.

First, the very fact that the use of frame enlargements has become so common and that fewer academics seek permissions from copyright holders itself sets a precedent. As I said, it’s common practice now. I assume there probably are still editors who would rather be safe than sorry and demand that the author obtain permissions for illustrations. I assume there are probably some authors who abide by that decision or who are themselves worried about copyright and so do seek and even pay for unnecessary permissions. As always in discussing this issue, I urge editors and authors not to seek permissions, since it sets a different and dangerous precedent, implying that fair use might not apply in such publications.

Second, there have been some interesting court cases which don’t involve film frames but which do suggest that fair use applies to the sorts of images that film scholars might wish to employ.

In August of 2006, a decision came down in the case “Christopher R. Harris v. San Jose Mercury News.” (See here for an article on the case from Communications Lawyer.) Like many other newspapers, the Mercury News had used a photograph from a book in a review of that book. The newspaper cropped the photo, including eliminating the copyright notice. Harris, the photographer, sued for infringement.

The closing argument was presented by Gary Bostwick, of the major law firm Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton, which works in, among other areas, entertainment law and intellectual property rights law. An abridgement of Bostwick’s argument for the reproduction of the photo as fair use is included in the article linked above. The article concludes: “The jury deliberated for only thirty-seven minutes before concluding that copying photographs from books for use in reviews was fair use.”

If a newspaper review can reproduce photographs, surely a scholarly book could claim an even greater right to do so.

Recently I sat down with my friend and colleague, James Peterson, of Godfrey & Kahn, S.C., who practices intellectual property rights law here in Madison. James got his Ph.D. in film studies at the University of Wisconsin. His dissertation (the committee for which David co-chaired along with J. J. Murphy) was subsequently published as Dreams of Chaos, Visions of Order: Understanding the American Avant-Garde Cinema (Wayne State University Press, 1994). The book contains frame enlargements, obviously vital in any attempt to analyze experimental films. James’s expertise in film studies and his subsequent law degree make him particularly attuned to the needs of scholars in the field and the rights involved in using images in academic publications.

During our conversation, I mentioned that many books using frame enlargements had been published since the SCS report was published. James responded:

On the frame enlargements issue, to me, really, although there’s no case law verifying the old SCS analysis from twenty years ago, I think it’s right. I don’t have any reason to doubt it. Now, I have a personal commitment to it myself, because I relied on it when I did my book. Nothing in my experience as a lawyer has led me to think otherwise … I think the position on frame enlargements is much more secure than on production stills. Marginally more at least.

I mentioned that David and I had also used production stills in our books without seeking permission. James responded:

I would think that those are fair, too. To me the biggest case is the Bill Graham Archives case (the district court case in the letter) and that was affirmed right down the line by the second circuit court of appeals. So to me that’s a huge fair-use case for scholars.

The case James refers to is one he cited to me in a letter summing up his opinions on the fair-use status of various kinds of illustrations that I wanted to use in The Frodo Franchise. The second circuit court of appeals he refers to is in New York, and it often handles major cases involving copyright law.

The case in question was “Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Limited, Dorling Kindersley Publishing, and RR Donnelley & Sons Company.” At issue were some illustrations in a book, Grateful Dead: The Illustrated Trip. This was a coffee-table cultural history of the band, done with the members’ cooperation. The book reproduced without obtaining permission seven images on which the Bill Graham Archives claimed copyright. There had in fact been some negotiations between the publishers and the archive, but as a fee could not be agreed on, the illustrations were reproduced without permission. The copyrighted images had been “originally depicted on Grateful Dead event posters and tickets.”

The court decided in favor of the publishers, declaring the reproduction of the seven images constituted fair use and thus upholding the lower court’s decision. In summing up, the court declared (using the four factors determining fair use listed above):

On balance, we conclude, as the district court did, that the fair use factors weigh in favor of DK’s use. For the first factor, we conclude that DK’s use of concert posters and tickets as historical artifacts of Grateful Dead performances is transformatively different from the original expressive purpose of BGA’s copyrighted images. While the second factor favors BGA because of the creative nature of the images, its weight is limited because DK did not exploit the expressive value of the images. Although BGA’s images are copied in their entirety, the third factor does not weigh against fair use because the reduced size of the images is consistent with the author’s transformative purpose. Finally, we conclude that DK’s use does not harm the market for BGA’s sale of its copyrighted artwork, and we do not find market harm based on BGA’s hypothetical loss of license revenue from DK’s transformative market.

James expressed his opinion about the decision: “At least on the use of illustrative material, I think that case is very powerful.”

Powerful indeed, because it suggests that film scholars would be justified under fair use even if they reproduced whole production photos, posters, and other visual material directly related to the discussion in the text of their book or article, all without seeking permission.

I mentioned the widespread use of frame enlargements and photographs on the internet, particularly on fan websites. James gave his opinion on the use of photos on websites and then on our blog particularly:

The stock-photo houses are best positioned to complain about that activity, because they’re in the business of selling into that market. So if you want to illustrate something on your website, you shouldn’t just snatch it and stick it on the website.

You guys are, to my way of thinking–what you are doing is almost infringement-proof, because you’re unimpeachably scholarly and you’re writing about the things that you’re copying. It would be different if you were just using it to illustrate your website. I think a lot of the fan sites might fall into that category. They’re not connecting scholarship about the thing. They’re using the things they’re copying to attract attention to their own work. That, I think, is a different enterprise.

All of this is good news for cinema studies. So yes, things have happened since 1993 that would change the situation for film scholars, and it’s all for the better. Fair use is obviously alive and well, and those of us who need to reproduce the images we discuss can do so. Let’s all go analyze a film!

Note: Important policy statements on fair use in related areas have been released in the past few years. For the use of copyrighted material in documentary films, see the Center for Social Media’s “Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use” (2005) and its follow-up on the statement’s impact.

In 2007, the Society for Cinema and Media Studies released a statement targeted at classroom teaching: “The Society for Cinema and Media Studies’ Statement of Best Practices for Fair Use in Teaching for Film and Media Educators,” in Cinema Journal Volume 47, no. 2 (2008) or online.