Archive for 2008

The boy in the Black Hole

PTU.

DB here:

Films from Hong Kong’s Milkyway company earn a lot of praise for their visual qualities. Shooting in Technovision, Johnnie To Kei-fung and other directors have created some of the most vivid and fluid imagery in contemporary cinema. But the movies have soundtracks too. What about them?

When I saw Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide (2000), I staggered out exhausted. I was overwhelmed not only by the delirious plot and its cascade of feverish imagery—who else puts the camera inside a dryer at a laundromat?—but also by what seemed to me the most elaborate soundtrack I’d ever heard in a Hong Kong film.

Shortly after seeing the movie, I visited the Milkyway headquarters and met Martin Chappell, the sound designer of Time and Tide. (For his credits and his company information, go here.) I figured that he could help me hear more in all movies, not just his own.

Years later, during my spring visit to Hong Kong, I got my wish. Martin gave me an interview and sent me several information-packed emails. As I’d hoped, he taught me to listen better.

At the console

Martin Chappell is a concussive burst of enthusiastic energy, an impression aided by the fact that he looks about sixteen. He loves moviemaking and sound design. Growing up in England, he started as a bass guitarist and audio fan, and he studied music and acoustics. When he graduated he worked in sound studios and became a roadie. After a year in Australia, he moved to Hong Kong and got a job in a radio station.

Soon he was working at TNT, creating sound effects for cartoons and dubbing American movies into Mandarin. Hired briefly away by MGM, Martin then shifted to Milkyway. His first effort there was helping on the mix for The Intruder (1996).

Now, with over fourteen years of audio engineering experience, he is sovereign of sound at Milkyway. Ensconced at the heart of Milkyway’s facility, Martin presides over what he calls the Black Hole. The company’s sound studio consists of several rooms, including a Foley studio that is a black hole within the Black Hole.

By Hollywood standards, these studios are minuscule. (Compare the mixing theatre I visited last year for 3:10 to Yuma.) As usual in Hong Kong cinema, work must be fast and tight. Martin typically has a sound crew of three, sometimes including Foley artists. Postproduction sound is usually allotted three weeks, sometimes a little longer. Often he has to prepare a mix on short notice so that visiting critics, festival programmers, or backers can preview a work in progress. As a result, Martin can be found in the Black Hole far into the night, blasting through reel after reel.

Waiting for no man

Most Hong Kong films have a bare-bones approach to sound: dialogue, music, and minimal effects. The sort of detailing that Hollywood offers, especially in Foley techniques, has not been common. There simply isn’t the time and money for a densely mixed track. A lot of time has to be allotted for dubbing the film twice, once in Cantonese and once in Mandarin for the mainland and overseas Chinese market. As a result, even the best Hong Kong films often have a dry, vacant ambiance, which is commonly masked by music. (Perhaps the wall-to-wall music in Wong Kar-wai’s films is an effort to supply a rich sound texture in the absence of other options.)

But Time and Tide had more resources. As part of a Sony initiative to expand into Asian production, which also yielded Crouching Tiger and Kitano’s Brother, it had a large budget by Hong Kong standards. Martin had three months for sound postproduction, “the longest schedule I’ve had in my life,” and a sound crew of eight.

Martin found Time and Tide “a beautiful learning experience.” Working around the clock under the tutelage of veteran postproduction supervisor Hui Koan (The Blade, The Legend of Zu), Martin was encouraged to take chances. He could create rich Foley tracks—remember the tinny ricochet of the little boy’s abandoned skateboard?—and he borrowed ideas from Fight Club, Gladiator, and The Matrix. He was layering sound in the Hollywood manner, albeit on a smaller scale. And he pushed toward wilder possibilities. He recalls the pleasure of putting jungle bird calls under early shots of clubbers wandering through nighttime traffic.

Out and about

Hong Kong looks lovely, but Martin thinks that it’s just as breathtaking in its noise—“a rich sonic soup.” Virtually every chance he gets, he heads out to record in the field.

I pretty much never leave home without my Edirol R-09, and I have a Zoom HR for portable hard disc recording.

It’s important to have a recorder with you all the time. You never know when some drunk is going to burst into song whilst lying in the gutter. In Sparrow, Simon Yam challenges Ka Dung to steal the cop’s handcuffs when they’re outside a bar late at night. So I just pulled the recording I’d made earlier of some drunk guys singing karaoke. It was late one night, I was walking back from the pub, and I heard it echoing out an alleyway.

I feel I’m incredibly lucky. I went out one night to get fresh recordings of a minibus for Linger. I’d scouted the spot, but when I got there the heavens opened and I didn’t have an umbrella. I ran to a nearby bridge—serendipity. I realize it’s next to a tram road, so I recorded buses and trams in the rain, and these sounds feature prominently in Sparrow.

Martin’s wife Marisha often comes with him, either operating or providing effects herself. Recording on the fly freshens up his library, and keeps him alert to new possibilities.

I’m always hoping for a gift from the Ear in the Sky. I’m actually trying to type quietly now, but there’s a band playing downstairs and it’s coming through the walls. They sound terrible, but I think it could be used for a bar scene—late night outside somewhere? . . .

You can see Martin on location in a two-part TV show here.

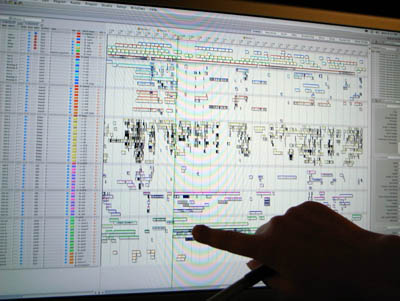

Back in the studio, Martin revels in software like his Digital Performer and Propellerhead Reason programs. His setup isn’t a Mercedes, like ProTools, he says, more of a Lexus—but in some ways it’s more flexible than the more famous option. Johnnie To wants rich tracks, so “Now I spend almost all my time on Foley and ambience.” Martin “finds the flavor” of the sound through his synthesizer.

I load a recording into Reason and I can play with it in real time on my keyboard—pitching it up or down, sweeping the filters, tweaking the equalization. I do so much with ambiance like this. Sometimes I tie it to the picture, other times I just play on a whim. . . . It’s almost fun.

Alongside his high-tech equipment, Martin employs some home-made items, such as his gobo panel, an upright mesh of stones that is virtually a sculpture (above). The gobo can muffle or redirect sound. Placed between two sources, it can allow clean recording of each track.

Every gun makes its own music

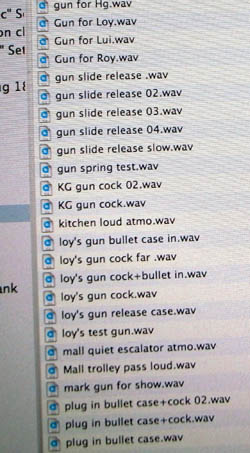

In The Mission, each of the five bodyguards gets a different pistol. Martin gave each one a different sound, labeled in his files by the actor’s name. Here “Roy’s gun” is sometimes coded as “loy’s gun,” and there are plenty of other discrete sound bits on file.

I asked Martin about the mall shootout, which has become a classic in the genre.

There seemed to be so much space in there, and we were adding artificial reverbs, but none of them seemed to work real well. That’s when we decided to experiment a bit, developing things we’d tried in A Hero Never Dies. We just put in the tail of a cannon firing. So that phrase “Bring out the big guns” is literally true here.

There was also a really long gap between some gunshots. We tried adding more, but it felt too busy. So we tried lengthening each gunshot, with the cannon tail reverberating. But that still wasn’t long enough, so we started playing with it, almost jamming with the music. We time-stretched the cannon tails, not just a bit like you’re supposed to. It gave a very artificial but tense sound. If you think it’s music, it might well be.

But even then it wasn’t long enough. So before the next pistol shot, we actually reversed the cannon sound. We get the reversed echo first, then we hear the shot itself! It feels like time has slowed down, then speeded up.

Martin might also have mentioned that these wavering gun reports swoop across left and right channels, creating a dynamic acoustic space for cinema’s most static static gunfight.

Martin also shared his thoughts on the role of sound in fleshing out characterization. After reading Walter Murch’s book In the Blink of an Eye he began to think about how to use sound subjectively. The result was the PTU scene in which Lam Suet, head bandaged, smoking in his car, suffers auditory hallucinations.

Martin acknowledges that there are plenty of conventions that audiences would miss if they weren’t present. When a character hangs up the phone on another character, the disconnected line is signaled through a beep or hum, even though this seldom happens in real life. Martin would also like to hear mobile phone calls in that “headphone bleed-through” effect. He’d also like to handle dialogue like that, “half-overheard, not fully comprehended.”

Still, he finds ways to bypass conventions. In PTU, when the officer played by Simon Yam is abusing the suspect in the video arcade, Martin avoided the library whacking sound, what he calls “the Foley kung-fu cloth flap.” Simon’s slaps are synched to explosions, whizzing missiles, and other arcade sounds. (I offer a visual analysis of one scene in PTU here.)

Ear in the sky

Martin believes that in most films, there’s an immediate need to establish the setting, the placement of the characters, and the scene’s mood. This is done through images, of course, but sound plays an important role. Often a wide shot orients us generally, while sound focuses on one zone of action in that space. “I would guess if you watch TV with no sound, it would be very difficult to really focus. Sound can bring out the visual and guide the eye.”

As an example, Martin walked me through a few moments in Sparrow. The elusive Chun Lei has gulled a quartet of pickpockets, and they pursue her to a rooftop. As the men explore it, we hear traffic and a distant plane, which evokes Chun Lei’s plan to flee Hong Kong.

They spot her on the roof. The suggestion that she might jump is underscored by distant traffic horns.

As the men approach Chun Lei, Martin added distant sirens and a soft wind.

An extreme long-shot provides a still broader sound canvas, with traffic sounds predominating.

In a much tighter shot, as the actors come closer to the camera, the ambiance thins and softens. “Now we time the traffic to underline the dialogue.” Chun Lei leans forward to kiss Bo, trying to provoke the leader Kei to jealousy. We hear echoes of a passing truck, almost as a warning.

Only professionals would probably notice these maneuvers, and there’s a reason. Martin thinks that sound can bypass the conscious mind, working directly on our most visceral impulses (fight or flight?). In this he echoes Gary Rydstrom, quoted in an earlier blog of ours: “Film sound is the side door to people’s brains.”

I’m grateful to Martin for all the time and effort he put into our interview. Next time I see a Milkyway film, or any movie, I’ll listen harder. You too?

Photo by Martin Chappell.

Goodbye to Hong Kong for another year

My Heart Is That Eternal Rose.

DB here, yet again:

Back nearly a week from Hong Kong, I’ve been swamped by backlog and made logy by jetlag. But I wanted to offer last-minute notes from this year’s film festival. I won’t comment on the films that disappointed me or that weren’t in finished form. Instead, upbeat reports, some pictures, and a trio of DVD delights.

On the big screen

Little Cop (1989) starring and directed by Eric Tsang, was part of the festival’s tribute to him. It’s a silly but ingratiating item that anticipates Stephen Chiau’s mo lei tau nonsense comedy. The opening credits are burned onto Tsang’s pudgy body, and thereafter a series of episodes takes him to the anti-prostitution squad (cue the condom jokes) and then the drugs detail. There are engaging gags around a funeral, with a song in praise of death set to the Colonel Bogey march, and lots of intrigue with a master criminal who can steal other people’s faces. Needless to say, since this is Hong Kong, we get many food gags too. Eric called in his bets and got a flurry of walk-ons from top stars like Andy Lau and Maggie Cheung. The only tedious stretch is the last scene, an uninspired clone of Steve Martin’s Absent-Minded Waiter routine. Otherwise, good dirty fun.

Paranoid Park (2007) seemed to me Gus van Sant’s best film in a long time, after the somewhat arid exercises of Gerry and Last Days. Here he’s got a genuine, gripping story that he can render in his detached but lyrical style. The shot of Alex in the shower is particularly gorgeous, and the tracking shot of his tormented walk through town is enhanced by swarms of subvocal recriminations that spurt out from all three channels. My friend J. J. Murphy has provided further commentary on his blog here and here.

If movies about moviemaking risk narcissism, movies about film school must be narcissism squared. The Early Years: Erik Nietzsche Part 1 (2007) centers on a young filmmaker who is transparently Lars von Trier. In-jokes about Danish film culture pile up, and the plot takes almost every easy way out, but Jakob Thuesen keeps the proceedings moving briskly enough. The caricatures are fun, although I think the all-night frenzy of film school life is better captured in Yanagimachi Mitsuo’s Who’s Camus Anyway?

A real revelation: And the Spring Comes (2007, above), by Gu Changwei. A somewhat homely woman with a crystalline singing voice imagines herself headed straight for the Beijing opera. Instead, broken love affairs and unwillingness to lower her ambitions keep her sequestered teaching music in a small town. A tough but touching melodrama rendered in a tactful style, with female lead Jiang Wenlei willing to be unsympathetic.

Many art movies can seem inert in their storytelling—over-under-dramatized, we might say. Carlos Reygados’s Silent Light (2007) escapes this trap. Slow and static, it is suffused with a stark calm that gives gravity to a love affair between a stolid farmer and a woman who runs a café. Planimetric compositions are used imaginatively, and the soundtrack makes daring use of offscreen noises. As an old Dreyer fan, however, I have to worry about the film’s relation to Ordet. Dreyer’s film isn’t exactly ripped off or cited, but it floats behind this one like a spectre before materializing at the climax, perhaps in overbearing fashion. Ordet, suffused with religious debate, earns its miraculous finale, while Silent Light, for all its austerity, is a film of the flesh, and its spiritual coda seems to me somewhat forced. But I’m willing to be convinced otherwise.

Because another guest didn’t appear, I was asked to introduce programs of films by or related to Maya Deren. I enjoyed the chance to see them again, and to reread her writings in the excellent collection Essential Deren. Her work remains stimulating—especially Meshes of the Afternoon and Ritual in Transfigured Time. Her writings blend a stringent formalism, echoing Rudolf Arnheim‘s views of cinematic specificity, and a fascination with myth and non-Western cultures. The boys’ Trance movies (Fragment of Seeking, The Cage, The Potted Psalm) are of historical interest, but hers remain lively. I was happy to see how many young people stayed after the screenings to discuss films that are sixty years old.

On the small screen

In my shopping, I discovered three fine movies on DVD.

*Do Over, a Taiwanese network narrative I liked in Vancouver back in 2006, now available with English subtitles in a so-so transfer (good color and contrast, blurry frame-by-frame pickup). A strong debut film from Cheng Yu-chieh.

*My Heart Is That Eternal Rose, an important 1989 Hong Kong film by New-Wave talent Patrick Tam. This mix of romance and crime stars Kenny Bee, Joey Wang, and a shockingly young Tony Leung Chiu-wai, and Christopher Doyle is listed as one of two cinematographers. The film’s daring stylization marks it as belonging to Hong Kong’s late-80s burst of creativity, and many moments look forward to the luxuriant melancholy of Wong Kar-wai. Clearly Tam (who edited Days of Being Wild and Ashes of Time) was an important influence on Wong. For a long time, I had access to My Heart only on an ugly pan-and-scan laserdisc, but now a widescreen transfer of a worn but bright print offers a considerable improvement. It’s far from perfect, with somewhat slurred movement, but better than nothing.

*Play while You Play, usually known as Cheerful Wind (1981), is Hou Hsiao-hsien’s second film, a romantic drama about a blind man and a somewhat self-indulgent television producer. It’s one of his three commercial “musicals,” and seldom seen, let alone discussed. I think that stylistically these films lay the groundwork for his Taiwanese New Wave films from The Sandwich Man onward. (Go here for more.)

I don’t enjoy this quite as much as his first film, Cute Girl, or his third, The Green, Green Grass of Home, which seems to me nearly a masterpiece. Still, there are lovely moments in Cheerful Wind, including the music montages and a surprisingly offhand ending. Hou films almost casually in the open air, letting passersby drift in and out of the frame (above). The disc, from something called Hoker Records, claims on its package to be 4:3, but it actually preserves the 2.35 format. Unfortunately, it does so through letterboxing, yielding only so-so resolution. No English subtitles. Rumor has it that the irresistable Cute Girl is available in a similar package.

In the point-and-shoot LCD

Four of the brains behind the festival: Ivy Ho, Bede Chang, Li Cheuk-to, and Albert Lee.

Shan Ding, man of all work at Milkyway Image, and the magisterial Peter Greenaway.

Mrs. Johnnie To, Johnnie To, Amy Lau, and Lau Ching-wan, who normally eats nicely.

Joanna Lee, translator extraordinaire and music facilitator to the world.

Jupiter Wong, ace photographer, and Bela Tarr after the enthusiastic reception of The Man from London. My takes on Tarr are here and here and here.

Peter Chan, whose Warlords just won a slew of prizes at the Hong Kong Film Awards.

Jacob Wong, Festival programmer, and Raymond Phathanavirangoon, lately of Fortissimo. I praised Raymond’s presskits last year.

Shu Kei and Michael Campi, just before the premiere of Coffee or Tea, which Shu Kei directed with Kwan Man-hin.

Tourist snap no. 1: Wherever you turn in Wanchai, there’s something interesting to see. Even air conditioners start to look like public sculpture.

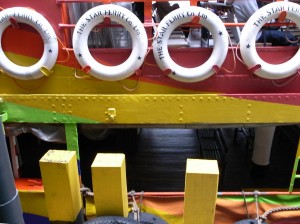

Tourist snaps 2 and 3: I often took the Wanchai ferry to screenings on Kowloon.

Tourist snap 4: Coming back late from a screening on the Kowloon side, I would walk past the old clock tower.

. . . A walk fortified by a late-night sample of the Sweet Dynasty’s almond and walnut soup.

In all, as I said at the start of my 3 1/2 weeks here: This will always be the place.

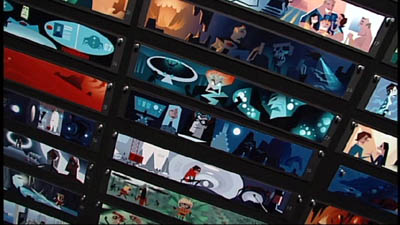

A glimpse into the Pixar kitchen

DB here:

On some of Bill Kinder‘s business cards, the I in PIXAR is represented by Buzz Lightyear, the blustery, not-too-swift astronaut of Toy Story. It’s a typical gesture of self-deprecation from the studio that showed that computer animation didn’t have to be just plastic surfaces and mechanical expressions. Pixar is cool, geeky, and warm all at the same time. Its films are both smart and soulful, made by movie fans for movie fans, and for everybody else. Like the best of the Hollywood tradition, Pixar movies have the common touch and still offer the most refined pleasures.

Kristin and I have already written admiringly about Pixar on this site (here, here, and here). It’s quite likely that this studio is making the most consistently excellent films in America today. So we were delighted when our colleague Lea Jacobs arranged for Bill to come to the University of Wisconsin—Madison last fall. He toured our new Hamel 3-D media facility, met with faculty and students, and gave a talk, “Editing Digital Pictures.” Bill is Director of Editorial and Post-Production, a position that gives him an encompassing view of the Pixar process as he champions the efforts of the editors and their teams as key creative contributors.

Kristin and I have already written admiringly about Pixar on this site (here, here, and here). It’s quite likely that this studio is making the most consistently excellent films in America today. So we were delighted when our colleague Lea Jacobs arranged for Bill to come to the University of Wisconsin—Madison last fall. He toured our new Hamel 3-D media facility, met with faculty and students, and gave a talk, “Editing Digital Pictures.” Bill is Director of Editorial and Post-Production, a position that gives him an encompassing view of the Pixar process as he champions the efforts of the editors and their teams as key creative contributors.

A graduate of Brown, where he studied with our old friend Mary Ann Doane, Bill is like Pixar movies—intellectual, good-natured, energized, and adept at connecting with people. He started his career in news-gathering and TV editing before moving to work at Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope, in the days of Jack (1996) and the uncompleted Pinocchio project. He joined Pixar in 1996, while they were finishing Toy Story. When the success of A Bug’s Life enabled Pixar to move to a purpose-built facility in Emeryville, Bill went along.

Whittling vs. building

I’ve always been uncertain about what an editor does in the animation process. Since every shot is planned and executed in detail, what can be left for an editor to do? Bill started from that question. No, editing digital animation isn’t just a matter of cutting off the slates and splicing perfectly finished shots together.

As in live-action filming, the animation editor is working with dozens of alternate versions of every shot. The reason is that at Pixar, there are roughly five phases of production: storyboarding, layout, animation, lighting, and effects/ rendering. Each one generates footage that has to be cut together.

The static storyboards, for instance, present poses, expressions, and movements against a blank background. They are assembled in digital files that can be played back as if they were a movie. In order to plan the next phase, the resulting “footage” has to be edited, and choices are made at every cut. And each scene is storyboarded at least five different ways, with many variations of action and timing. A single film uses up to 80,000 boards!

At the next phase, layout, the scene’s overall action is planned. Layout artists develop the staging of each shot, testing different backgrounds and camera angles with the editors. Again, the alternatives have to be assembled and cut in various combinations.

Whittling versus building, Bill called it. The live-action editor gets a mass of footage that has to be triaged, but the animation editor is building and tuning the film from the start. Editing operates at each phase, from storyboarding to final rendering. This “almost overwhelming iteration,” as Bill called it, demands that the editorial department hold all the alternatives in its collective mind at once. Add to this the fact that Pixar can take up to five years to produce a film, maintaining several editorial teams to cover projects at different degrees of completion. When you realize that all this brainpower and bookkeeping are necessary for even the simplest shot, you appreciate the felicities of the finished product even more. These people make it all look easy.

Continuity and the viewer’s eye

Bill explained that digital animation occasionally requires something like live-action coverage. (1) Action sequences with fast cutting need to be spatially clear, and “chase scenes can be hard to board.” So sometimes the layout artists create master shots and closer shots from different angles that the editor will pick out and assemble, live-action fashion.

Like live-action editors, Pixar editors have to keep an eye on continuity of the objects in the frame. Because each shot is reworked across many phases, items of the set, lighting, color, atmosphere, effects and rendering have to be maintained, on many layers or levels of the program. (I gather it’s like the layers in PhotoShop.) Sometimes a layer, whether a prop, character, or set element, fails to “turn on” and so a discontinuity can crop up. A finished Pixar film typically has 1500 shots or more, so there’s a lot to keep track of.

In another carryover from live-action features, Pixar plots are conceived and executed in three discrete acts. It’s not only a storytelling strategy but a convenience in production. Rather than waiting until the entire film is done to examine the results of the different phases, the filmmakers can finish one act ahead of the others in order to troubleshoot the rest.

I’ve studied how filmmakers compose the image in order to shift our attention (2), so I was happy to hear that this process is of concern to the Pixar team. “Guiding the viewer’s eye,” Bill called it. He explained that in looking at storyboards and animated sequences, his colleagues sometimes use laser pointers to track the main areas of interest within shots and across cuts, especially when characters’ eyelines are involved. Nice to see that sometimes academic analysis mirrors the practical decisions of filmmakers.

The auteurs of Pixar

What makes Pixar films so fine? Bill supplied one answer: It’s a director-driven studio. As opposed to filmmaking-by-committee, with producers hiring a director to turn a property into a picture, the strategy is to let a director generate an original story and carry it through to fruition (aided by all-around geniuses like the late Joe Ranft). Within the Pixar look, John Lasseter’s Toy Story 2 and Cars are subtly different from Brad Bird’s The Incredibles and Ratatouille or Andrew Stanton’s Finding Nemo and upcoming Wall.E.

Bill covered many other fascinating topics, including the importance of sound (“the animated film’s nervous system”). But I’ll end with some pull-quotes from Bill’s talk.

*Francis Ford Coppola: “No film is ever as good as its dailies or as bad as its first assembly.”

*Gary Rydstrom: “Film sound is the side door to people’s brains.”

*Bill himself: “Editing is just writing, but using different tools.”

We’re grateful to Bill for his visit and look forward to seeing him again. Goes to prove what we’ve said before: Popular American filmmaking harbors many of the most intelligent, sensitive, and generous people you’ll ever find.

(1) In live-action production, coverage involves shooting a master shot of a scene that shows the entire action. Then parts of the action are repeated and filmed in closer views. This allows the editor several options for cutting the scene together.

(2) I talk about this in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style and throughout Figures Traced in Light. See also Film Art, pp. 140-153, and this blog here and here.

PS: Another glimpse into the kitchen: Bill Desowitz reports on Wall*E at Animation World. Now Pixar is trying to emulate the look of 70mm. And there’s footage from Hello, Dolly! in there? All the signs point to another nutty, dazzling achievement.

Lines of sight and light

DB here:

Two weeks ago the film critic and historian Paul Arthur died. (An obituary is here.) Apart from being a warm and robust man, Paul advanced our understanding of cinema in important ways. He was a committed teacher and an energetic writer. For years it seemed that almost every issue of Film Comment or Cineaste contained an essay by him. Although he had an encyclopedic knowledge of film, he wrote with particular brilliance about experimental work. His book, A Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (2005), reflects a lifetime of sensitive study.

Paul was naturally on my mind as I watched the avant-garde films on display here at the Hong Kong Film Festival. I’ve mentioned some in an earlier entry, but I wanted to signal others that seemed to me especially fine.

A set by Ben Rivers had quiet poetic overtones. Very short (We the People lasts only one minute), they center on landscapes. I especially liked House (2007), a spectral suite of images derived from a miniature house Rivers contrived.

Lewis Klahr‘s Antigenic Drift (2007) was a lovely and funny meditation on, I think, air travel in a post-9/11 age. Glossy images of airports are haunted by wandering bar codes, boarding passes, and anatomy drawings. Tablets burst out of blister packs and gather in colorful rank-and-file formations. The film bears the traces of Klahr’s visit to Wisconsin, some details of which are here.

Lewis Klahr‘s Antigenic Drift (2007) was a lovely and funny meditation on, I think, air travel in a post-9/11 age. Glossy images of airports are haunted by wandering bar codes, boarding passes, and anatomy drawings. Tablets burst out of blister packs and gather in colorful rank-and-file formations. The film bears the traces of Klahr’s visit to Wisconsin, some details of which are here.

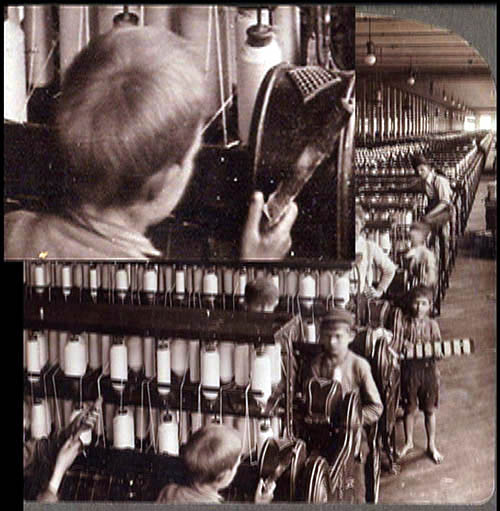

Ken Jacobs is a legendary figure in the avant-garde. Prolific, outrageous, and wide-ranging in his interests, he has been at it for fifty years. His oeuvre includes the casually goofy Little Stabs at Happiness (1960), the epic Star Spangled to Death (1957-2004), and the classic Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969). There Jacobs dissected a 1905 Biograph film on the optical printer (see P. S. below), revealing not only isolated faces and gestures in its crowded shots but also abstract masses of light and dark, and even the grain of the film stock.

Across several years, Jacobs and his wife Flo have developed a mode of multiple-projection performance. Their Nervous System shows films at different speeds, halts them, drops down filters, even superimposes slightly different frames from prints of the same film, creating vivid 3-D effects. Such spectacles trigger comparisons to nineteenth-century impresarios of wonder: the conjuror who calls up ghosts, the sideshow entertainer whose calliope happen to be a movie machine. (1)

Capitalism: Child Labor (2006) might at first seem a rerun of Tom, Tom. A photograph shows men and boys at work in a thread factory. This dire image, with the workers’ flat expressions only adding to the sadness, might suffice in itself. But Jacobs takes the picture to pieces and shows us everything. He creates close-ups and long-shots, embedding them within one another to create games of scale. And then? Informed by Nervous System discoveries, Jacobs takes things a step further.

The picture originated as a stereoscope card. A stereoscope card consists of two side-by-side images, shot at angles corresponding to the difference between our eyes. Looking at the card through the viewer, the viewer has an illusion of 3-D. (Remarkably, my top illustration also features a factory scene.) For a detailed account of stereoscopy, see the Wikipedia entry.

Jacobs intercuts the two slightly different photos, often allotting only a single frame to each. With simple geometric shapes this procedure would yield “wiggle stereo,” as illustrated in the Wikipedia piece. But the density of the images evidently allows Jacobs to create a fluttering, nagging sense of volume. We seem to move just a bit around the figures and their workstations before popping back to our starting place, then launching again, endlessly. Somehow my brain thinks I’m spasmodically starting to circle through the factory.

This is why we’re right to call such films experimental. They often try to discover how our senses, our minds, and our emotions reveal themselves in their encounter with cinema. The goals are different, I grant you: Art exposes, science explains. But scientists should have a special eagerness to study avant-garde films. I can’t imagine anyone interested in filmic perception—and not just cognitivist film researchers—who wouldn’t find Capitalism: Child Labor a provocation to marvel at how our vision jumps to conclusions about depth. This movie makes us say Wow.

Song and Solitude, a 2006 film by Nathaniel Dorsky, was simply stunning. (2) In the Brakhage tradition, it’s woven out of lyrical shots of details seized and abstracted. Reflections, silhouettes, out-of-focus textures, veils and grids shedding unexpected ripples of light: everything seems radiant. Sometimes you recognize a familiar object, like a window screen pebbled with rain. Often, though, you have to ask: What am I seeing? And then Why don’t I ever notice this?

Dorsky’s Buddhist-influenced aesthetic, revealed in his book Devotional Cinema, drew this commentary from Paul Arthur:

Old School doesn’t describe it. Dorsky has achieved such a subtle mastery over the most basic means of cinematic expression–composition, duration, juxtaposition–that he can squeeze a wealth of emotional vibrations out of the silent, seemingly banal interplay of foreground and background objects. A formalist with a brimming, elegiac soul, Dorsky will gently rock your attitude toward cinematic landscape. His world is a sublime mystery measured by patience and unmatched visual insight.

I didn’t know Paul well. I met him around 1974, when we had a good conversation about landscape in Anthony Mann. We ran into each other occasionally over the years and corresponded a little.

His generosity to Kristin and me came through on several occasions. In a roundtable discussion published in October no. 100, he called attention to the fact that Film Art tried to remind students and teachers of the importance of avant-garde film. (3) In reply to an essay of mine in Film Quarterly, he sent overabundant praise but added several pointed questions that forced me to tighten up my argument. Most vividly, when I was criticized (some would say personally attacked) in the pages of Film Studies’ most prestigious academic journal, he was moved to write me with encouragement. Of my critic he wrote: “To hell with him if he can’t take a joke.”

Like a great many others, I will remember Paul with affection and admiration.

Song and Solitude.

(1) An engrossing interview with Jacobs can be found here.

(2) By the sort of coincidence I like, Song and Solitude also played the Wisconsin Film Festival, which I had to miss this year. Trusty Joe Beres of the Walker Art Center, still a Badger at heart, provides coverage.

(3) The discussion is here, but beyond the first page the material is proprietary.

P. S. 21 May 2009 Keith Sanborn wrote me to point out that, in a reply to Ed Halter (who discusses Anaglyph Tom (Tom with Puffy Cheeks) in Artforum), Ken Jacobs corrects the frequent claim that the 1969-71 Tom, Tom was made on an optical printer. No, says Jacobs; he rephotographed the movie from the screen. Here is the inimitable explanation Jacobs supplied to Halter.

The movie so pushes forward the character of film projection. Images explode out of darkness. Nor was I using a specialized analytic projector that with a steady flicker minimizes exchange of frames. I used what had been a common RCA home sound-projector, from the 1940’s, possibly the late 1930’s, but one with a hand-controllable clutch that allowed for slowing and even stopping the film. Freezing as it’s called but usually more like burning. A heat-shield would fall in place to protect the film from burning but would then darken the image, and so I removed it and took my chances with burning. The energy that is light was a featured and constant presence in the work. Darkness is death and the old reclaimed images constantly struggle against death to proclaim themselves. Release of energy, via intermittent projection or in the return of rambunctious ghost-actors, was much of what the work was about.

Thanks to Keith for calling my attention to this.