Archive for 2008

Title wave

The very first drafts of the outline always had Cloverfield on them. . . . Cloverfield was what I always wanted to call the movie. . . . It’s a terrible title . . . if you’re trying to sell something, who the hell’s gonna go see that?. . . But it’s cool. There’s a reason. I could state the reason, but it’s very clear it is meant to be obtuse. I believe that the film answers why it is called Cloverfield, I believe that it’s in the film, I believe that you can make that argument. It says exactly what I want it to say. But it’s very clear that we don’t want to explain it.

Screenwriter Drew Goddard, at Creative Screenwriting podcast

DB here:

Don’t think about a movie title too long. Even a familiar one can turn strange before your eyes.

This was brought home to me long ago when I showed Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan in a course. Before the film started, a student asked me, “Who is it?” I didn’t understand. “I mean, who is her fan?” It never occurred to me to take the title this way, but actually in the movie Lady W does attract a big fan.

Titles can be explicit, but they’re often metaphorical, associative, and oblique. Sometimes they’re downright obscure. But as Drew Goddard says, they can be cool.

Don’t Worry, We’ll Think of a Title (1966)

The least provocative titles are based on the protagonist’s name: Brubaker, Anthony Adverse, Erin Brockovich, Norma Rae, Speed Racer. One step removed is the title that describes the protagonist’s job or role: Gladiator, Hitman, The Cable Guy, Bob le flambeur, perhaps also The Godfather. Then there are the titles, like The Last Action Hero or Prince of Players or Little Caesar, that characterize the protagonist more figuratively.

If the movie has a pair of protagonists, the title can reflect that, as in David and Bathsheba, Pete’n’Tilly, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. When the title elevates a secondary figure, as in Melvin and Howard or Harry and Tonto, it has the effect of making us consider the relationship between the two as central to the action. When there are several main characters, we can get a title characterizing the group, not just Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice but The Professionals and The Breakfast Club.

Things get a little more curious when the title focuses on a character other than the protagonist(s). Rebecca identifies a dead character, but her aura haunts the (unnamed) heroine. Both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much refer, at least literally, to a minor figure. Why is The Wizard of Oz not called Dorothy Goes to Oz? Why does Mizoguchi’s great Sansho the Bailiff take its title from the name of the villain? It’s not as if Mizoguchi was trying to do an Ian Fleming (Dr. No, Goldfinger).

Perhaps Wizard and Sansho bear their titles because they’re adapted from literary sources that had those titles. But that just pushes the problem back a step: Why do the originals have these titles? And in asking why, I’m not asking for information about what went on in an author’s mind or a story conference. The why question here is about purpose and function. What does the title do in relation to the film’s plot or theme?

For instance, you can argue that the title of The Wizard of Oz works to highlight the seductive world of Oz, so different from Kansas, with the Wizard himself being a figure with one foot in fantasy and one in reality (since the Wizard is actually a prairie mountebank). Similarly, I’m inclined to say that Sansho the Bailiff’s title reminds us of the socially sanctioned cruelty at its center. Zushio and Anju, the fugitive brother and sister, may each escape in a different way, but Sansho’s world remains; it is our world.

Some titles are simply place names, like Casablanca, Macao, Philadelphia, or New York, New York. Others specify dates: 1860, 1900, 1941, 1984. In both strategies, the title often evokes symbolic associations or parallels with the here and now.

The title can refer to the core situation, as with Back to School or Being John Malkovich, or to a key scene, as in Sophie’s Choice and Gunfight at the OK Corral. This can get abstract and metaphorical. Housekeeping features a very offbeat approach to housekeeping. The Birth of a Nation characterizes America reborn after the Civil War. Being There describes more or less all that the cipher-like hero does. The title can even predict the action, as in The Great Escape, A Man Escaped, and Killing of a Chinese Bookie. In these instances we have anomalous suspense: Why and how will an announced action be carried out?

Reaching for the Moon (1917/ 1930/ 1933)

More rarely, the title can refer to the film’s central formal device. Through Different Eyes and Vantage Point announce that they will play with subjective point of view. The Blair Witch Project justifies its title by posing as a dossier of found student footage. The Prestige warns us that a magic trick’s surprise payoff might well be matched by one at the end of this movie. Kristin and I have long assumed that the title of Tati’s Play Time refers not only to the anarchic relaxation unleashed in the Royal Garden restaurant but also to the movie’s own perceptual strategy of making us see amusement in banal incidents.

Hitchcock, the tireless formalist, provided titles that give away his game. Rear Window announces a stationary viewpoint and a limited field of action. More fancifully, you could take Rope as announcing the film’s sinuous long takes. Family Plot is nicely equivocal, referring at once to a communal grave, a conspiracy among kin, and of course the movie’s own mysterious plot of knotty kin relations.

Then there are the generic characterizing titles, usually single-word titles like Notorious or Spellbound or Pushover or Identity or Slacker or Speed or even, probably most generic of all, Conflict (borne by at least five films, from 1916 to 1955). Here again, though, we can find puzzles.

We know why Homicidal is called Homicidal, but what purpose is served by calling a movie Psycho? Again, the source book provides the title, but Robert Bloch’s novel is narrated in the first person and the title gives us a big clue about the sort of mind we’re in. Hitchcock’s film presents the story more objectively, and it begins with Marion Crane’s theft. Those critics who see the film as blurring the boundaries between sanity and insanity would say that Marion, who impulsively commits a crime, and Norman are points on a continuum. People we take to be normal have irrational impulses, a point reinforced by Norman’s line, “We all go a little mad sometimes. Haven’t you?” After their conversation about private traps, Marion seems to recognize herself in his question.

Same old song (1997)

Many titles are citations or quotations, and they usually highlight a thematic element. Both Yankee Doodle Dandy and Born on the Fourth of July are drawn from the same song: both offer portraits of patriotism, but in very different keys. Pennies from Heaven is highly, perhaps heavily, ironic, something you can’t say about Meet Me in St. Louis.

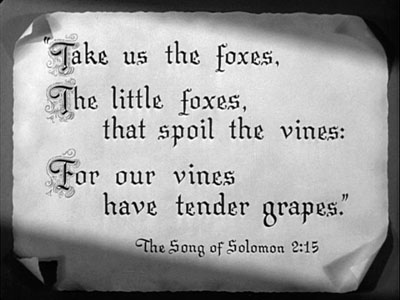

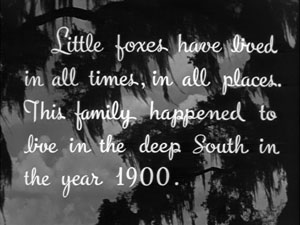

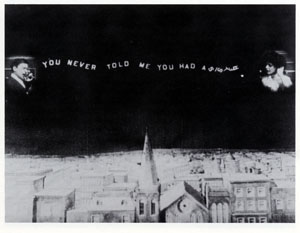

Not all citations are as transparent as these. The Little Foxes explains its title in a prologue, seen above. The Bible verse is then linked to the story we’ll see.

We’re ready to understand the family as creating a milieu that could easily corrupt the tender vine, Xan.

A catch phrase can work too, such as The Sweet Hereafter or It Takes a Thief or It’s a Wonderful Life. You Can’t Take It With You emphasizes pursuing fun rather than riches. Phffft suggests that a couple has split, but how would you explain that outside the U. S.? (The French title is, perhaps surprisingly, Phffft.)

Some catchphrase titles suggest the sort of multiple meanings we saw in Family Plot and Play Time. All That Jazz packs a lot into three words: most basically, a flurry of trivial stuff (pushing our hero into overdrive), but also music and the heights of emotion (being jazzed). You Only Live Once at first suggests seizing the moment, but by the end of the film you begin to think it implies: “Who could bear to live twice?” I especially like The Best Years of Our Lives, which also changes its significance across the film. The bulk of the movie asks: The returning servicemen have given their prime years for us, but how do we reward them? By the end of the movie, the title seems to be suggesting that their best years, of healing and self-understanding and integration into families, lie ahead of them.

I’ve known students, especially from outside the U. S., to have trouble with His Girl Friday. It’s a two-tiered reference. First is Robinson Crusoe’s “man Friday,” his aboriginal servant. But in American slang, a girl Friday is the boss’s closest female assistant, an all-around tough worker and troubleshooter. That’s what Hildy is to Walter Burns, until she decides to marry Bruce and move to Albany. She reverts to her girl Friday role in the course of the film, as the title has predicted she would.

We don’t always know when a quotation is at work. I have always found Some Came Running obscure. The phrase isn’t used in the film, or in the text of the James Jones source novel. But the novel’s epigraph takes a passage from Mark 10: 17:

And when he was gone forth into the way, there came one running, and kneeled to him, and asked him, Good Master, what shall I do that I may inherit eternal life?

This is the passage where Jesus asks the rich man to give all that he has to the poor, apparently as unlikely an event then as now. The problem is that in the Biblical passage, only one came running. The reader has to imagine several characters in the novel as “running” to ask how they will get into heaven. But the citation seems to me a mismatch, since the characters of novel and film aren’t all rich. In any case, without the epigraph tacked to the movie, its significance gets lost. This doesn’t stop me from liking the title, though.

One of my favorite instances of the obscure catchphrase-title is Ozu’s I Was Born, But . . . To decipher it you have to know that during the Depression, Japanese college graduates often couldn’t find work, and the sentence “I graduated, but . . . ,” trailing off, suggesting “. . . I’m unemployed,” was a topical one at the time. Ozu in fact made a film with that title. But then he decided to have fun with it, making a college comedy called I Flunked, But . . . Then came an even sillier extension: When he makes a film about boys, it becomes I Was Born, But . . . [I still have problems…]. Our parallel, I suppose, is the move from Honey, I Shrunk the Kids to Honey, I Blew Up the Kid.

Which reminds me: Titles have a strange habit of speaking for the character. We have I Was a Teenage Werewolf, I Dood It, I Love Melvin, Me and the Colonel, My Favorite Brunette, My Cousin Vinny, Blackmail Is My Life, and so on. This convention points up the difference between literature and film. A book with one of these titles would lead us to expect first-person narration, and it would be strange if it didn’t. A movie with such a title might provide voice-over commentary from the protagonist, as How Green Was My Valley and I Walked with a Zombie do, but more likely it won’t.

For Your Eyes Only (1981)

Many titles seem enigmatic when you first hear them. They create curiosity and build up an urge to check out the film. In most cases, the mystery gets cleared up in the course of the movie. Erik Gunneson’s Milk Punch does this through a bit of action, but more commonly the title is clarified in a line of dialogue or a motif. You have to wait for the very end of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? or Rio Bravo to get a reference to the title. A good embedded title shifts its meanings, as Best Years does. One scene of Silence of the Lambs explains the title’s relevance to Clarice’s character and shows what drives her to pursue Buffalo Bill. By the end of the film it points toward a moment when her inner pain will start to fade. And the title may reverberate beyond that moment, pointing to larger themes of injured innocence in a world of slaughter.

Sometimes the title is more oblique. Take North by Northwest. Many critics believe that it refers to Hamlet’s confession that “I am but mad North-northwest: When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.” Roger Thornhill, caught off balance by the espionage game he’s plunged into, could be said to have lost his bearings. But I’ve always thought that the compass-point title logo and the cross-hatched latitude/ longitude array that launch the movie prepare us for travel, in a roughly westerly, then northwesterly direction (New York-Chicago-South Dakota). And when Roger is sent from Chicago to Rapid City, he travels by airliner: He flies north, by Northwest. A Hitchcock joke?

We occasionally encounter a title that isn’t explained in the course of the action, so we are invited to ponder its implications. 8 ½ is a famous example; insiders know Fellini treated it as an opus number (seven features + two shorts + this new feature = 8 ½). American Graffiti can refer to the transitory events of the single night the film shows—the kids have scrawled their dramas on the town in one long summer blast. But I think you can also read the title as referring to the pop tunes that engulf and comment on the action. Americans write their graffiti on the airwaves.

In recent times Hong Kong films have tried to make their English-language titles more comprehensible, but in the golden years there were some delirious ones. We had Banana Cop, Wheels on Meals, Why Wild Girls, Gun Is Law, Tiger on Beat, Devil Fetus, Burning Sensation, Boys?, Kung-Fu vs. Acrobatic, Evil Black Magic, Ghost Punting, Takes Two to Mingle, Vampire’s Breakfast. . . Even Chungking Express and Ashes of Time aren’t straightforward. A real problem in studying Hong Kong films seriously is to explain to people that a movie called Police Story or Naked Killer can be pretty interesting. And if the titles don’t perturb them, the subtitles will.

But most of the Hong Kong titles are inadvertently puzzling, sort of accidental surrealism. Of course Surrealist filmmakers have given us many willfully meaningless titles, such as Emak Bakia and The Andalusian Dog. Arguably Brazil and even A Hard Day’s Night are in this vein (although I think that both of these can be explained in roundabout ways).

Today’s American films seem drawn to recherché titles. I heard Jonathan Caouette remark that he chose the title Tarnation for reasons he couldn’t specify; it just seemed to fit. One catchphrase, “the elephant in the room,” has founded two movies, but in such an abbreviated form—Elephant—that you might not recognize the link. I never thought I’d find synecdoche on a movie credit, since few Americans know how to pronounce it, let alone know what it means. But trust Charlie Kaufman to give it a try. (He also inadvertently stole a pun I’ve been using in film theory courses since the seventies.) But at least I think I get the title’s point, given the protagonist’s obsession to build a miniature city. Other titles are flat-out baffling.

Take Reservoir Dogs. Tarantino says “it’s more of a mood title, it just sums up the movie, don’t ask me why.” (1) I like the title. I just don’t understand why it works so well. Do certain dogs guard reservoirs, as some guard junkyards? Are these guys as vicious as dogs, as dirty as dogs, or doggy in the sense of losers, or what? In other words, why does it seem more fitting than, say, Sump-Pump Ferrets?

Despite the logo showing faces spilling out of a blossom, Magnolia doesn’t explain its title unless you dig around outside the film. During the rain of frogs, the traffic collisions take place on Magnolia Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley. So in a way, Magnolia is one point of convergence for several of the story lines that crisscross the plot. But that’s pretty thin motivation.

What about Syriana? Before I went to the film, I had heard that the title referred to an imaginary, prototypical Middle Eastern territory used in Pentagon war games and computer simulations. But Stephen Gaghan, in another Creative Screenwriting podcast, supplies details:

It was a real term. I heard it for real in a very conservative think-tank, where they said, “We’re going to redraw the map in the Middle East, we’re going to make a new country out of Syria, Iraq, and Iran—the borders of ancient Persia, less Pakistan. We’re going to call it Syriana.” I’m like, “Excuse me? Would you repeat that?” So I shot it, I had William Hurt explaining it. But I didn’t think it helped at the end of the day. We’re not going to make a new country in the Middle East right now.

As he saw the collapse of America’s invasion of Iraq, Gaghan came to believe that explaining the title would date the movie.

I wanted to go for a title that couldn’t be pegged to right now. You notice there’s no reference to Iraq in the movie, there’s just the most passing reference to 9/11, which was an improv thing we did, and there’s no Israel. I wanted the more permanent sense of what it is inside of men, particularly men in the west, that makes them believe that they can remake any region to suit their own purposes. . . . I wanted it to be specific to the film, not to the time. So that if you think about the tone of the film, when you think about what happened in the movie, it would only be Syriana, and Syriana could not skid into some other reference point.

Then there’s Cloverfield, which I’ve discussed earlier this year. Part of the movie’s mystique is that nobody can agree on what the title refers to. The creature? Central Park, where the video camera is found? An exit on California Interstate 10, near where producer J. J. Abrams has his office? On this last option, screenwriter Drew Goddard says no way:

If we would do that, we would be dicks. We would be assholes.

I don’t want to get into the labyrinthine question of the relations of Cloverfield to Lost and to the film’s viral marketing campaign online. What interests me is the fact that part of the fun around, if not exactly in, the film is playing with all these possibilities . . . and waiting to see if a sequel will explain further. Perhaps a teasing title can help get people into theatres for a followup movie.

Finally, Primer. Not only do I not understand the significance of the title; I don’t know how to pronounce it.

I Love a Mystery (1945)

Why have we seen such a rise in cryptic titles in recent years? Several factors seem important. A puzzling title lifts your film above the clutter and creates buzz as people wonder what this movie could be about. This buzz factor is multiplied by the Internet. The title can be researched through Google and discussed endlessly in chatrooms. Filmmakers know that we can revisit a film on video whenever we want, so the movie can be rescanned by eager eyes searching for clues to the title’s meaning. Mystery titles summon up the geek in us.

Which means that the current wave of peculiar titles probably owes a lot to Tarantino. In the interview I already cited, Tarantino stressed that that title of Reservoir Dogs let the audience play with the possibilities.

The main reason that I don’t go on record is because I really believe in what the audience brings. . . . People come up to me and tell me what they think it means and I am constantly astounded by their creativity and ingenuity. As far as I’m concerned, what they come up with is right, they’re 100 percent right. (2)

But then, as Jonathan Walley pointed out to me, cool opacity isn’t confined to movie titles.

Band names have always been evocative: The Rolling Stones weren’t literally rolling stones, The Pixies not literally pixies. But what many of them evoke now strikes me as much more obscure and, to quote Grandpa Simpson, “weird and scary”: System of a Down, Teeth of Lions Rule the Divine, One Day as a Lion, My Morning Jacket, etc. Many of these are alternative bands, and many of the films with these obscure titles are alt/indie films, or at least films with those pretensions, so there’s a parallel there, I’d say. The willful obscurity of title, of band or film, evokes an ironic, think-outside-the-box, you’re-not-meant-to-get-it indie attitude that appeals to the intended audience.

That is, obtuse titles for an acute public.

For comments, suggestions, and memory-jogging, thanks to the Badger Filmies: Susan Antani, Colin Burnett, Andrea Comiskey, Sydney Duncan, Stew Fyfe, Jason Gendler, Doug Gomery, Jonah Horwitz, Tristan Mentz, Jason Mittell, Tim Palmer, John Powers, Brad Schauer, Chris Sieving, and Jonathan Walley.

(1) Quoted in “Reservoir Dogs Press Conference,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerald Peary (Oxford: University of Mississippi Press, 1998), 38.

(2) Some writers have hazarded that the title derives from Tarantino’s awkward pronunciation of Au revoir les enfants, coupled with Straw Dogs, but as far as I can tell, this relies on a second-hand source–ie, a former girlfriend–and Tarantino hasn’t confirmed it.

Is there a blog in this class? 2008

Kristin here—

One year ago today, I wrote the first “Is There a Blog in This Class?” entry. The idea was to point Film Art: An Introduction users toward past entries that might prove useful in relation to various topics in the textbook. The beginning of the autumn semester seemed a good time to survey what has been posted here. We plan to make such surveys an annual feature of the blog. [For the 2009 entry, go here.] After all, there are over 200 items by now, and that number increases by about one per week. We also use the “Film Art: The Book” tag for entries that we think might be pedagogically useful, so you can always check there for updates.

From its first appearance in 1979, Film Art has offered a large and broad selection of examples illustrated by frame enlargements. Space considerations, however, always limit us to a few images from all but our most important examples. One enormous advantage of the blog is that we can use as many illustrations as we need. Some of the entries listed below can be useful as supplementary examples that go into more precise detail than we can in the textbook.

Some general entries

DVD supplements can be very useful for teaching, but many of them are lightweight fare, with actors and major crew members talking about how wonderful their colleagues are. Film Art suggests some more substantive supplements. More recent recommendations appear in “Beyond praise: DVD supplements that really tell you something.”

These days students are likely to encounter filmmakers talking about their own work, whether on talk shows, in DVD supplements, or in scholarly collections of interviews. In studying films, we need to examine their statements, which sometimes can be misleading. David ponders the question, “Do filmmakers deserve the last word?”

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

If you have aspiring filmmakers in your class, you might want to direct them to David’s “The magic number 30, give or take 4,” on the age at which most directors get started.

Chapter 2 The Significance of Film Form

During the spring of 2008, there was a lot of talk concerning the supposed decline of film criticism. In response, “In critical condition” elaborates on the four activities laid out in Chapter 2: Description, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation.

Chapter 3 Narrative as a Formal System

“A behemoth from the Dead Zone,” on the monster movie Cloverfield, discusses the concept of restricted narration in detail, touching on other Hollywood examples as well.

Virtually all the films used in Film Art are good examples of whatever technique or formal property we’re discussing. For Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, we pick apart the problems with motivation, progression, and character. We end with some comments on Steven Spielberg’s directorial style.

Two essays on David’s website deal with narrative issues. “The Hook: Scene Transitions in Classical Cinema” examines how classical Hollywood films use small-scale patterns to guide the spectator from one scene to the next. “Anatomy of the Action Film” analyzes the plot structure in Mission: Impossible: III using a number of concepts discussed in Film Art.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In “Hands (and faces) across the table,” analyses of three long takes from films made decades apart—Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007), Akira Kurosawa’s The Most Beautiful (1944), and Cecil B. De Mille’s Kindling (1915)—demonstrate the use of staging to subtly direct the viewer’s attention within the frame. This entry could be equally useful in exploring the long take in Chapter 5.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

Aspect ratios may seem a narrow, esoteric subject—especially to students! But “Godard comes in many shapes and sizes” uses many pretty pictures to demonstrate just how important framings are and how they can be distorted in DVDs. Students may be less resistant to letter-boxing after reading this.

Our discussion of 3D technology in Beowulf, “Bwana Beowulf,” also considers film style and how filmmakers so far have failed to find new ways of adjusting classical Hollywood style to 3D. People tend to have strong feelings one way or the other on the introduction of 3D, so this issue would probably generate a lively discussion.

The “Sleeves” entry compares framing techniques in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes and Kenji Mizoguchi’s A Woman of Rumor (an analysis which could be equally useful in discussing editing).

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

While at the Hong Kong Film Festival in April, 2008, David interviewed Johnny To’s editor, Tina Baz, on dealing with the complexities of shifting point-of-view in Mad Detective. Unfortunately at this point the film hasn’t been released in the U.S., either theatrically or on DVD; it is, however, available in the U.K. The interview contains massive spoilers that students shouldn’t encounter before they’ve seen the film. If Mad Detective does become available, however, it would be a challenging film to show in a unit on editing. If you’re teaching an upper-level analysis course or an introductory one to film majors, this one will get them talking. It also provides vivid examples of rapid shifts in point of view.

In “Some cuts I have known and loved,” David analyzes brief segments from five films, each centering on a particularly ingenious, striking, or flagrant cut. These are not the familiar examples usually summoned to demonstrate editing.

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

My “What does a Water Horse sound like?” covers a session of final sound mixing for Walden Films’ The Water Horse, with flashbacks to watching sound sessions for The Return of the King. David got another insight into the complexities of sound mixing in an interview with Martin Chappell, sound editor of several Johnny To films and Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide. He wrote it up as “The boy in the Black Hole.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

In “Your trash, my treasure,” David reflects on the children’s action genre as revived by the National Treasure films.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

“Manhattan: Symphony of a great city” analyses Amos Poe’s epic, mesmeric Empire II, a structural film based on a complex rendering of imagery recorded from a single window. The gorgeous frames will make both you and your students (at least the curious, perceptive ones among them) want to see the film. At three hours, it’s difficult to squeeze into a class screening, but even a generous excerpt would convey something of its fascination.

“Lines of sight and light” describes some recent experimental films, including Ken Jacobs’ Capitalism: Child Labor (2006).

In “Tracking Aardman creatures,” we presented a brief history and chronology of the great Bristol-based animation firm, responsible for Creature Comforts and the Wallace and Gromit series. If you’re showing an Aardman film in class, this will give you plenty of information on the company and on DVD availability as of January, 2008.

If you’re showing your students Warner Bros. cartoons, “Pausing and chortling: A tribute to Bob Clampett” might be useful. It gives some additional information about animation techniques and incidentally points to a teaching technique you might want to use in class.

Pixar consistently creates some of the best films (not just animated films, but films) coming out of Hollywood. It’s good news that the company is increasing its rate of release. By next spring, WALL-E, Bolt, and Up will have appeared in less than a twelve-month period. We got a fascinating glimpse behind the scenes when Bill Kinder, Director of Editorial and Post-Production, visited Madison. Some of what he said is summarized in “A glimpse into the Pixar kitchen.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Critical Analyses

Few of our entries offer in-depth analyses of single films, but “Cavalcanti + Ealing = a little-known gem” examines the narrative of Went the Day Well? and puts it into historical context. “Cronenberg’s Violent Reversals” compares the narrative structures of A History of Violence and Eastern Promises, while “Three Nights of a Dreamer” goes shot by shot through a sequence from In the City of Sylvia.

Chapter 12 Film Art and Film History

Film Art’s final chapter includes a section “The Development of the Classical Hollywood Cinema (1908-1927),” which outlines the early formulation of continuity editing. In “Happy birthday, classical cinema!,” posted December 28, 2007, we celebrating the 90th anniversary of the crucial year, 1917, when classical editing patterns crystallized into a system that has endured, with variations, ever since. We discuss some of the subtleties of the continuity guidelines of the time, with plenty of examples.

A related entry, “Rio Jim, in discrete fragments,” examines shifts in technique during the development of continuity editing, concentrating on several William S. Hart westerns of the mid-1910s. Another entry, “Lucky ‘13,” discusses the transitional year 1913 through two masterpieces that represent quite different styles.

“All singing! All dancing! All teaching!” is aimed primarily at teachers using Film History: An Introduction, who would be likely to devote a lecture and screening to the subject. Still, Film Art users might find it useful, either in relation to Chapter 9 or for the brief section on the coming of sound in Chapter 12. It assesses several documentaries on the coming of sound that had recently come out on DVD. Even for those who don’t want to show them in class, they yield considerable information. (One of the DVDs also deals with color technology up to the introduction of three-strip Technicolor in the 1930s.)

“Superheroes for sale” deals with recent trends in the American film industry.

Other entries

Although most of our entries could be read by an undergraduate, we don’t make a point of writing them for students. “Observations on Film Art and film art” has a wide readership, including other cinephiles, journalists, industry people, bloggers, filmmakers, and scholars in the other arts. A few of our entries go beyond the level of an introductory class. If you teach graduate students or have bright and enthusiastic undergraduates looking to learn more, you might, for example, steer them to this item: “Minding movies,” a brief summary of cognitive film theory, with lots of links for those who want to go further in this direction.

When we go to film festivals, we post reports on the movies we see, the old friends we re-connect with, and the new ones we meet. On a regular basis, we visit the Hong Kong, Vancouver, and Wisconsin festivals, as well as Roger Ebert’s “Ebertfest.” These entries are chatty and sometimes specific to films that students may never get a chance to see. They would be difficult to link up with Film Art. Still, they give a sense of one major aspect of film culture and show part what their textbook authors do when they’re not preparing new editions. We haven’t listed those entries here, but you can find them by clicking here or on the Festivals category on the blog. If you’re interested in a particular film or filmmaker, try a search. Perhaps we’ve said something on the subject.

When we launched “Observations on Film Art and film art,” we tended to post every few days. This year we have tried to settle into a steady, once-a-week rhythm, with new entries typically going online between Thursday and Saturday. For those teachers who might want to assign their students to read the blog regularly, we hope this schedule makes that easier.

Lucky ’13

The Mysterious X (1913).

Each film is interlocked with so many other films. You can’t get away. Whatever you do now that you think is new was already done in 1913.

Martin Scorsese, quoted in Scorsese by Ebert (University of Chicago Press, 2008), 219.

DB here:

Most historical events don’t abide by clocks and calendars. Seldom does a trend begin neatly on one date and end, full stop, on another. Changes have vague origins and diffuse destinies. When Kristin and I, along with others, argued for 1917 as the best point to date the consolidation of the Hollywood style of storytelling, we realized that it’s a useful approximation but not as exact as a Tokyo subway timetable.

It’s just as hard to argue that a year constitutes a meaningful unit in itself. Who expects anything but tax laws to change drastically at midnight on 31 December? Yet evidently our minds need benchmarks. Film historians, while being aware that trends are slippery and dating is approximate, have long spotlighted certain years as particularly significant.

Take 1939, which has become a sort of emblem of the peak achievements of Hollywood’s Golden Age. We had Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Only Angels Have Wings, Stagecoach, Gunga Din, Wuthering Heights, Dark Victory, Young Mr. Lincoln, Beau Geste, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Ninotchka, The Roaring ‘20s, and Destry Rides Again. I’d watch any of those, except Gone with the Wind, right now—something I find it hard to say about most Hollywood movies I’ve seen in 2008.

Another strong year is 1960, with La Dolce Vita, L’Avventura, Rocco and His Brothers, The Apartment, Elmer Gantry, Spartacus, Psycho, Exodus, The Magnificent Seven, Shadows, Late Autumn (Ozu), and The Bad Sleep Well (Kurosawa). Arguably, 1960 was owned by the French, who gave us Breathless, Shoot the Piano Player, Paris nous appartient, Les Bonnes femmes, Le Trou (Becker), Moi un noir (Rouch), and Letter from Siberia (Marker). (See Postscript.)

Let’s go back still further. Researchers sometimes split the silent-film period in two, with the first stretch, usually called “early cinema,” running up to 1915 or so. (1) The second phase then runs roughly from 1915 to 1928. (2) So for many historians the year 1915 functions as a tacit pivot-point, and it is remembered not only for The Birth of a Nation but also for Regeneration, The Tramp, Kindling, The Cheat, Les Vampires, Daydreams (Yevgenii Bauer), and several William S. Hart films. But another year holds a special place in the minds of silent film aficionados.

Over a decade ago, the annual Days of the Silent Cinema festival (Il Giornate del cinema muto), took 1913 as its focus. (3) It was an extraordinary year. Denmark produced Atlantis (August Blom) and The Mysterious X (Benjamin Christensen). From France we had L’Enfant de Paris (Leonce Perret), Germinal (Albert Capellani), and Louis Feuillade’s Fantomas series. Germany gave us Urban Gad’s Engelein and Filmprimadonna and Franz Hofer’s obsessively symmetrical The Black Ball. The staggering set of Italy’s Love Everlasting (Ma l’amor mio non muore!, Mario Caserini) was matched by the breadth of Enrico Guazzoni’s Quo vadis? In Russia Bauer released Twilight of a Woman’s Soul. American audiences saw Traffic in Souls (George Loane Tucker) and Death’s Marathon and The Mothering Heart, from a guy named Griffith. Several historians would argue that 1913 marked the first major achievements of film as an artform.

Two outstanding films of that annus mirabilis have recently been issued on US DVD. One is a striking accomplishment, the other a flat-out masterpiece. Both discs belong in the collections of everyone who’s serious about cinema.

Your call is important to us

A wife and her baby are alone in an isolated house when a tramp breaks in. As the wife tries to keep the invader at bay, her husband happens to telephone and learn what’s happening. He scrambles to return home. He steals an idle car, and its owner, accompanied by police, race after him. We cut rapidly between the besieged mother and the husband’s frantic drive, as he is in turn pursued. Just as the tramp is about to attack the wife, the husband bursts in, followed by the police. The family is saved.

This is the story of the 1913 one-reel film, Suspense, co-directed by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley. If the plot sounds familiar, it’s probably because you know that one of D. W. Griffith’s most famous films, The Lonely Villa (1909) tells the same basic tale.There are still earlier versions, including one, The Physician of the Castle (Le Médécin du chateau, 1908), which may have inspired Griffith. The ultimate source seems to be a 1902 play by André de Lord, Au téléphone (translated here).

So Weber and Smalley are reviving an old idea. Their task is to make it fresh. How they do so has been studied in depth by Charlie Keil in his book Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking, 1907-1913.I can’t match Keil’s subtlety, and it’s better that you see the film first, so I’ll drop only some hints, pointers, and comments.

We’re inclined to say that The Lonely Villa influenced Suspense. But maybe we can capture the situation in a more illuminating way. The art historian E. H. Gombrich has suggested that we can often trace the relationship between artworks in terms of schema and revision. (4) A schema is a pattern that we find in an artwork, one that a later artist can borrow. Most often, later artists copy the schema straightforwardly. This is the usual way we think of influence. But instead of replicating the schema, the next artist can revise it. She can elaborate on it, strip it to its essence, drop parts and add others, whatever—in order to achieve new purposes or evoke fresh responses.

In The Lonely Villa, Griffith uses crosscutting to build suspense. He cuts among the thuggish vagrants trying to break in, the wife and daughters trying to hold them off, and the father learning by phone of the situation and then plunging after them with a policeman. The obvious pattern here is the principle of alternation between different lines of action, all taking place at the same time and converging in a last-minute rescue.

So Smalley and Weber inherit the crosscutting schema, but they go beyond simply copying it. They find ways to revise it, some quite surprising. These revisions aim to create more tension and to dynamize the situation.

The obvious option, at least to us today, would be to use more shots than Griffith does; we think that increasing the cutting pace builds up excitement. Interestingly, however, Suspense uses only a couple of more shots than The Lonely Villa within a comparable running time. (5) We usually expect that American films become more rapidly cut as the 1910s go on, but this isn’t the case here. Shortly, I’ll suggest why.

Smalley and Weber recast Griffith’s parallel editing in several ways. For instance, The Lonely Villa prolongs the phone conversation between husband and wife, building suspense through the husband’s instruction to use his revolver on the thugs. Suspense, by contrast, doesn’t dwell on the telephone conversation but devotes more time (and shots) to the chase along the highway. That’s because Weber and Smalley have complicated the chase by having the husband pursued by the irate motorist and the police, something that doesn’t happen in the Griffith film.

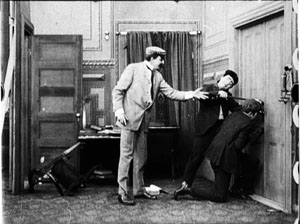

Just as important, Smalley and Weber revise the crosscutting schema through framings that are quite bold for 1913. For example, Griffith’s tramps break into the house in long shot, and they move laterally across the frame.

But Weber and Smalley’s tramp sneaks steadily up the stairs, into a menacing extreme close-up.

Elsewhere, Suspense gives us close views of the wife and of the door as the tramp breaks in. There are oblique angles on the back door of the house, and virtually Hitchcockian point-of-view shots when the wife sees the tramp breaking in and he looks straight up at her.

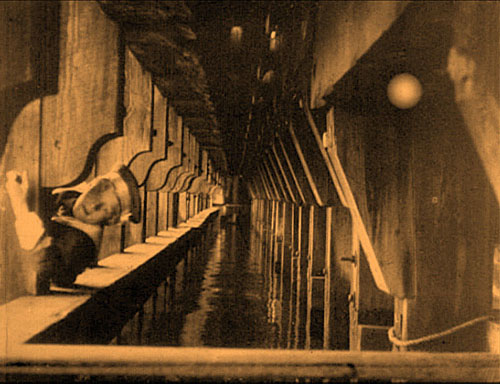

What struck me most forcibly on watching the film again was the way in which Weber and Smalley’s daring framings serve as equivalents for parallel editing. In effect, they revise the crosscutting schema by putting several actions into a single frame. The most evident, and the most famous, instances are the triangulated split-screen shots. They cram together three lines of action: the wife on the phone, the husband on the phone, and the tramp’s efforts to break into the house (here, finding the key under the mat). (6)

Split-screen effects like this were common enough in early cinema, especially for rendering telephone conversations. Eileen Bowser points out that the three-frame division was one variant, with a landscape separating the two callers. (7) Her example is from College Chums (1907).

But my sense is that in early cinema the split-screen effect was used principally for exposition or comedy, not for suspense. Smalley and Weber have made this framing substitute for crosscutting: instead of giving us three shots, we get one, showing the plot advancing along different lines of action. These splintered frames function much like Brian De Palma’s multiple-frame imagery in Sisters, Blow-Out, and other films. There’s also the nice touch of the conical lampshade over the husband’s head, providing a fulcrum for the composition.

Earlier in the film, instead of crosscutting between the tramp outside and the wife indoors, Suspense gives us both in the same shot, with the tramp peeking in behind her.

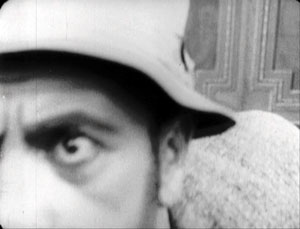

A more ingenious revision of the crosscutting schema comes during the shots on the road. Instead of cutting between the father in the stolen car and the police pursuing him, Suspense packs them into the same frame. This is done not only in long shot but also in striking depth compositions.

Flashiest of all are the shots showing the pursuers reflected in the rear-view mirror of the father’s car as he races ahead of them.

Again, a single framing has done duty for two shots, one of the father looking back and another showing the cops coming closer to him. By compressing several lines of action into a single frame, our 1913 film doesn’t need to use significantly more shots than the 1909 one.

These are just a few of the imaginative ways in which Weber and Smalley have recast their standard situation. I could have considered as well the unobtrusive use of the knife as a multi-purpose prop, the echoed shots of mirrors, and the shrewd employment of repetitions in the intertitles.

It would take an early-cinema specialist like Keil to trace out all the connections between Suspense and other films of its era. One among many would be the fact that Griffith wasn’t exactly standing still between 1909, the year of The Lonely Villa, and 1913. For instance, his Battle at Elderbush Gulch, made about the same time as Suspense (though released in 1914), displays far more rapid cutting than Weber and Smalley attempt. Griffith also employed a swelling advance to the foreground, like that of the tramp shot I showed above, in The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912).

Here, Smalley and Weber seem to have replicated a schema that was believed to ratchet up tension, the so-called looming effect.

The very title of the film exhibits self-consciousness about its artistic purpose. By 1913, it seems, American filmmakers were confident enough in their skills to announce their aims. We want, the title seems to say, to arouse you, to make you wait, hanging there, for the resolution. We know how to tell a twelve-minute story cinematically. The film seems uncannily to anticipate all those one-word titles that Hitchcock invoked to unsettle us–Suspicion, Spellbound, Psycho, Frenzy. As in a Hitchcock movie, the fact that we are pretty certain how Suspense will turn out doesn’t seem to dissipate our anxiety. (For more on this paradox of suspense, see this entry.)

Tunnel vision

It was during the Pordenone 1913 season that the full brilliance of Victor Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm hit me. I had seen the film a couple of times before and found it deeply moving in its restrained treatment of a poignant situation. The film traces the dissolution of a family. Sven Holm is doing a brisk retail business, but his health problems, along with a thieving clerk, plunge the family into poverty. When Holm dies, his wife Ingeborg must take the children into the poorhouse, and from there they are boarded out to foster families. Her plight worsens over the years, and its sorrowful depths are revealed when her son, now grown, returns to visit her.

Ingeborg Holm has long been recognized as a milestone in European film, not least for its effect on improving Sweden’s treatment of the poor. (8) The acting style is muted and delicate, with no mugging or arm-waving. For long periods, the main actors turn from the audience. (9) Just as impressive are the poised compositions, sustained in unhurried long takes. These give what is essentially a bourgeois tragedy a kind of majestic relentlessness. Watching, I remembered what Dreyer had admired in Sjöström’s Ingmar’s Sons (1918):

The film people here at home shook their heads because Sjöström had really a boldness to let his farmers walk heavily and soberly as farmers do. Yes, they used up an eternity to come from one end of the room to the other. (10)

But sitting in the Cinema Verdi in 1993, I spotted yet another level of artistry. Knowing the story of Ingeborg Holm, I was able to watch the shots unfold. I could study how Sjöström was unobtrusively moving characters so that they became shifting centers of interest. Although he didn’t cut in to close-ups, he harmonized his actors’ movements so that at one point you noticed Ingeborg, at another her husband. Performers spread themselves across the frame, arrayed themselves in depth, turned from or toward the camera. Most subtly of all, one actor might mask another one, driving our attention to other parts of the frame. Sjöström could sustain this intricate play of blocking and revealing for minutes on end.

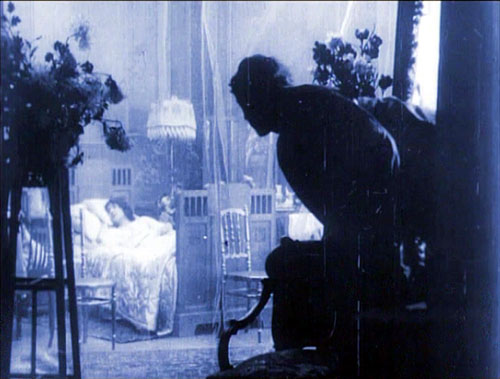

My favorite example of this tactic is the three-minute passage showing Ingeborg’s daughter and son taken away by new mothers. You can read the whole discussion on pp. 191-195 in On the History of Film Style (1997), but here is an excerpt, with stills intercalated. (These stills, grabbed from the DVD, lack a little on the left. The film has been printed and reprinted so many times, and now fitted to the TV monitor, that it has lost some information along that edge.)

Ingeborg’s entry with her children from the rear doorway establishes the trajectory that will be followed during the scene, as foster mothers come in and take away the children. (Again, the scene is built around movements toward and away from the camera.) In a brilliant stroke, Sjöström immediately plants the young son in the foreground, back to us. The boy will stand there immobile for this first phase of the scene, occasionally serving to block the superintendent.

Ingeborg buries her face in her daughter’s shoulder at the precise moment the foster mother enters from the rear left. She passes behind Ingeborg, and as she is momentarily blocked, the superintendent twitches into visibility, handing the woman a document to sign.

During the signing, when the woman is briefly obscured, the superintendent shifts position again and Ingeborg lifts her face once more. Then Ingeborg and her daughter move slightly leftward as the foster mother comes forward.

This phase of the scene concludes with the departure of the daughter and the embrace of Ingeborg and her son in the foreground, once more concealing the superintendent.

Granted, I picked one of the film’s most exactingly staged scenes, but there are several other examples. Consider the climax, when the adult son comes to visit Ingeborg: the camera position and staging ask us to recall the scene I’ve just mentioned. Or take a look at the handling of the space behind the counter in the various scenes in the Holms’ shop. One instance surmounts this section.

This choreography is hard to catch on the fly: by the time you notice a change, what prepared for it has gone. To understand the overall dynamic, we must reverse-engineer the effects, moving backward from the result to the conditions. As I studied the film, it became clear that creating shifting centers of interest was basic to the scenes’ effects. All the finesse of acting, both solo and ensemble, would come to little if we weren’t primed to watch the most important area of the shot. Directors of the 1910s became supremely skilful in guiding our eye from one major story point to another within the fixed frame.

Some of the tactics of guiding our attention could be borrowed from other arts. Painting and theatre supplied certain schemas, like placing an item in the center of the picture format and turning faces toward the viewer. But some tactics for directing our eye relied on capacities that were as “specifically cinematic” as cutting was argued to be. Theatre is staged for many sightlines, but cinema is staged for a single one, that of the camera lens. That fact allowed directors to organize the unfolding action in depth, prompting the viewer to notice things at many distances from the camera.

It also allowed a precise blocking and revealing of information that would not work on the stage. In a live theatre performance, the slight shifts we detect in the Ingeborg Holm scene would be apparent to only very few viewers; people sitting in other vantage points wouldn’t see them. For another example of this phenomenon, go elsewhere on this blogsite.

There’s a more basic explanation of what’s going on. Cinematic space is a result of optical perspective, like the space of classic painting. The actors may seem to be standing in a cubical space, but in fact they move within a tipped-over pyramid, with the tip resting at the camera lens. They work inside a ground area that’s the shape of a slice of pie. Here’s a reminder from The Black Ball.

When there are figures close to the camera, as here, they fill up more of the frame, indicating that the field of view has narrowed. Filmmakers of the 1910s had discussed this property of their “cinematic stage,” so as researchers we can confirm that the control of position and timing we observe on screen results from the firm intentions of the makers. They might have echoed Uccello, the Renaissance artist who bent over his drawings late at night and exclaimed: “How sweet a thing is this perspective!”

Suddenly the tableau tradition made sense to me. Directors had to organize both the two-dimensional composition and the tapering three-dimensional playing space in front of the camera. The purpose was to create ever-changing centers of interest, laterally and in depth, flowing along with the key moments in the unfolding action.

By studying the same tactics in Feuillade, Bauer, and others, I found that these principles offered a fruitful way to understand much of what was happening in the films of the tableau era. The dynamic of schema and repetition/revision was at work as well, since I found earlier, more rudimentary uses of these principles; these were then refined during the 1910s. Moreover, the idea helped me generalize beyond that era and analyze later directors, including Mizoguchi Kenji and Hou Hsiao-hsien, who also used staging to shape the viewer’s experience. The results can be found in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. Those books largely owe their existence to that flash of awareness kindled by Ingeborg Holm. (11)

We can’t reconstruct Sjöström’s stylistic development with much confidence. (12) His first directed film, The Gardener (Trädgärdsmästaren, 1912) survives, but I saw it before I knew how to watch 1910s movies in this way, so I can’t comment on it. Of the twenty-six films he made from 1912 to 1917, nearly all have been lost. Apart from Ingeborg, I have managed to see Havsagamar (The Sea Vultures, 1916). This retains aspects of the tableau tradition, but virtually no scenes display the intricate staging of his 1913 masterpiece.

In the late 1910s, judging by the films we have, Sjöström seems to have moved quickly toward continuity editing in the American vein. (13) The Girl from Stormycroft (Tösen frän Stormyrtorpet, 1917) contains extended passages of analytical editing, and the scenes display a freedom of camera setup one seldom sees in European cinema of the period. Sjöström clearly understands the principles of continuity down to the smallest detail. For instance, he not only uses the frame-edge cut (the cut that lets a character exit one shot and enter another, as the body crosses the frameline); he accelerates it. Our heroine leaves the kitchen, and in the shot’s final frame she hits the right edge. Another director would have had her exit the frame entirely and held the kitchen shot a little longer, to give her time to get to the next room. But Sjöström simply cuts to her already in another room, completing her trajectory.

Sjöström presumes that the constant pace of her approach and the vector of her movement will smooth the shot-change. It does, but few directors of that day would had such confidence that our mind would create continuity of motion.

During this summer’s archive viewing, I spent some time studying Sjöström’s cutting in The Girl from Stormycroft and subsequent films. I may offer some more thoughts later. For now I’ll just say that in these early years we seldom encounter such a versatile director, one who mastered the tableau tradition and then moved, with apparently little effort, to nuanced continuity editing. More generally, examining his technique isn’t a dry exercise. We never lose by studying craftsmanship. Sjöström’s films succeed because his style carefully guides our moment-by-moment apprehension of the heart-rending stories he has chosen to tell.

Have I convinced you to surrender your credit-card number? Suspense is available in a dazzling Flicker Alley collection, Saved from the Flames, compiled from the French series Retour de flame. Ingeborg Holm comes with a tinted print of the estimable Terje Vigen (A Man There Was) on a DVD from Kino. The latter disc includes vibrant scores from Donald Sosin and David Drazin.

(1) For the purposes of the outstanding Encyclopedia of Early Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2005), the editor Richard Abel considers that the early cinema constitutes the period from film’s invention ca. 1894 to the mid-1910s.

(2) Silent films were still made into the 1930s, notably in Russia and Japan—a situation that shows the rough-and-ready quality of period divisions.

(3) For an informative series of articles around the 1913 theme, see Griffithiana no. 50 (May 1994).

(4) Gombrich proposes these ideas at various points in Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation, new ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000). The book is a milestone in twentieth-century humanistic inquiry.

(5) The Lonely Villa (1909) has, in the version I’ve seen, 54 shots in a 750-foot reel (that is, about twelve and a half minutes at 16 frames per second). Suspense has nearly the same number of shots, 56, in about the same running time.

(6) Sharp-eyed readers will recognize one of these shots as Fig. 5.82 in Film Art: An Introduction, 8th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008), 187.

(7) Eileen Bowser, The Transformation of Cinema 1907-1915, vol. 2 of History of the American Cinema (New York: Scribners, 1990), 65.

(8) For more background on the film, see Jan Olsson, “‘Classical’ vs. ‘Pre-Classical’: Ingeborg Holm and Swedish Cinema in 1913,” Griffithiana no. 50 (May 1994), 113-123.

(9) Kristin wrote about this technique in “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1995), 65-85. She also discusses it in our Film History: An Introduction, 2d ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), 67.

(10) Carl Dreyer, “A Little on Film Style,” Dreyer in Double Reflection, ed. and trans. Donald Skoller (New York: Dutton, 1973), 133.

(11) I was probably primed for this by lectures presented by Yuri Tsivian, who has long been studying mirrors in 1910s cinema and calculating how they revealed offscreen space.

(12) Detailed information on Sjöström’s relation to the film industry in these years can be found in John Fullerton’s epic Ph. D. thesis, The Development of a System of Representation in Swedish Film, 1912-1920 (University of East Anglia, 1994). See also Fullerton, “Contextualising the Innovation of Deep Staging in Swedish Film,” Film and the First World War, ed. Dibbets and Hogenkamp, 86-96.

(13) Several people have analyzed Sjöström’s editing. Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 133-136 shows how cutting supports the acting in a crucial scene of Ingmar’s Sons. Tom Gunning’s essay “‘A Dangerous Pledge’: Victor Sjöström’s Unknown Masterpiece, Mästerman,” in John Fullerton and Jan Olsson’s anthology Nordic Explorations: Film before 1930(Sydney: John Libbey, 1999), 204-231, argues that Sjöström’s cutting gives his characters a degree of psychological opacity. Most recently, in an unpublished paper Jonah Horwitz discusses patterns of performance, composition, and editing in Terje Vigen (1917).

Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (1913).

PS 31 August: Some corrections. David Cairns writes to point out that the triangle at the top of the frame in the Suspense split-screen isn’t a lamp but simply the shade behind the father’s head, cropped by the masking. Wishful thinking on my part, I’m afraid. By the way, David has an intriguing movie giveaway going on his site.

Roland-François Lack corrects dates on two of my Greatest French Hits from 1960: “The great Marker from that year is Description d’un combat, not Lettre de Sibérie (1958), and likewise Rouch’s Moi un noir is from 1958.” Thanks to him and David. To my original list, I should probably have added Cocteau’s Testament d’Orphée, released in 1960.

Comic-Con 2008, Part 3: Two newbies share thoughts

Autographs are big: Richard Taylor signing books about the designs for The Chronicles of Narnia

Kristin here–

Back in the early days of this blog, I posted an entry on our friend Henry Jenkins and his concept of the “aca/fan,” a scholar who studies fandoms while being a fan him- or herself. At that time his book Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, had recently come out, and I highly recommended it. Fortunately the book has had a well-deserved success. On October 1 it will be coming out in paperback.

In that entry, I described Henry and our long friendship with him:

Henry doesn’t study fans to find out what makes them tick. He knows that. He’s one of them, a participant in fan cons, a player of video games, an explorer of the multimedia sagas like those of Star Trek and The Matrix that have grown up in the age of franchise culture. He received his doctorate here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where David was his dissertation advisor, and we have followed his career, as they say, with great interest. Straight out of the gate he was hired by MIT, where he is now the Director of the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities.

(You can find Henry’s blog, “Confessions of an Aca/Fan,” here. He interviewed me when The Frodo Franchise was published; you can find that in three parts, here, here, and here.)

The Frodo Franchise dealt with fan culture as well in Chapter 6, on fan-originated websites. Convergence Culture deals to a considerable extent with modern transmedia franchises. Yet neither of us had ever been to that Mecca of fandoms, Comic-Con. Of course, this year, when I got invited to participate on TheOneRing.net’s panel on the Hobbit project, I accepted. I emailed Henry just in case he happened to be going as well. It turns out he was, being on a long driving vacation through the west with his wife and son.

At first I thought maybe we could meet up early in the Con and then get together afterwards and share our impressions. (We bloggers look for material anywhere we can find it, and this seemed like a golden opportunity.) In fact we didn’t meet early on. There was so much going on, and we never glimpsed each other in the course of the entire event—not surprising, really, when you consider its size. But I made cell-phone contact on Sunday, and we sat down in my hotel lobby and spoke our thoughts into a microphone. Here are some excerpts.

(We talk about what we went to—him to the TV previews, me to artists’ presentation.)

On Different Tracks

We started off by talking about what we had each concentrated on.

HJ: It’s very clear that it’s like six or seven different conventions I could have gone to in the course of the weekend, and it would be a totally different experience depending on which one you went to.

KT: Yeah, I had that impression that there were probably people here mainly to buy stuff, some people here mainly to see celebrities and get autographs and so on.

HJ: And even on that there was a split between the film and the TV people. And there’s a whole comics track. Under other circumstances I would have just been spending my entire time at comics panels, because they’re the strongest comics sessions anywhere in the country.

Coming Alone vs. Having Something Specific To Do

KT: I was happy that I had something to anchor myself, though. I don’t think I’d like to come here, at least for the first time, alone and not having anything specific to do.

HJ: Luckily Henry and Cynthia were along, but it was overwhelming a bit, trying to negotiate and keep up with three people in a space that congested. So that was its own kind of challenge. Sometimes I was thinking it would be great just to be a single person navigating through the space and not have to have large-scale logistics! The scale of it just blows you away. I’ve been on the floor at E3, which is supposed to be one of the largest entertainment trade shows. I’ve done South by Southwest. But neither of them are anywhere near the scale of Comic-Con.

The Scale of the Event

KT: They always say 125,000, because that’s the number of tickets they sell, but then you’ve got all the exhibitors and the people who are presenting on panels. It must be another few tens of thousands packed into that building.

HJ: Yeah, at least.

KT: I was kind of amazed that it worked as well as it did

HJ: Yeah, they did a remarkable job in just managing crowd control. Getting people in and out of things with some degree of order. Some more bullying guards than others, but it was probably necessary to keep the peace.

KT: Yeah, there were a LOT of guards and guides and so on, but people seemed really to be polite, on the whole. I was taking the shuttle bus from a hotel down the street [from my hotel] every day and then coming back by shuttle bus. This morning the bus was quite late compared to other days. It was supposed to come every ten minutes, and we were there maybe twenty. And people who were arriving made this very neat horse-shoe shaped line on the sidewalk. It was very orderly.

HJ: Almost no signs of anyone breaking in line, despite the intensity of some people’s desire to get into things. Someone commented behind me about ‘honor among geeks,’ and that’s probably a good description. There’s a strong honor code.

KT: The venue seems to be up to having that many people in it. I hardly had to wait for rest rooms at all.

HJ: No, the facilities are good.

We ended up doing a fair amount of what they call here “camping,” which is sitting in several panels in a row because there was something we really wanted to see. But you end up trapped in a space with no access to food. Hall H at least has rest-room facilities in the space.

KT: I didn’t try that myself, that is, camping. But I was going to this action-figure panel because it involved Toy Biz, which did the action figures for Lord of the Rings. I heard from people in line that a lot of them were there for the next panel, which was on Sanctuary, which I know from nothing, but they were very devoted and were saying, “They shouldn’t have put this in such a small room.”

HJ: There is a certain sense that you vote with your body at Comic-Con. One of my newest fandoms is Middleman, which is a new ABC family show, and it was in a small room, but we packed it. There was a sense of accomplishment. The producer looked out and said, “This may be the whole audience for the show,” because it hasn’t gotten much publicity yet. There was a sense that just being there was show of support for things.

KT: I wonder how many of the companies have people at those panels—in the audience. I hadn’t realized it, but there was somebody from New Line—who’s probably not from New Line anymore—and then some Warner Bros. people, supposedly, sitting out in the audience for the Hobbit one. That kind of surprised me. Why bother?

HJ: At the larger sessions it seemed they had blocked off four or five rows of space just for the studio people. Rarely were they occupied to anywhere near that extent, so it was maybe overkill. But there were a few sessions where there were a significant number of people. The Battlestar Gallactica, for example. There was a large studio contingent there for that. Suits and friends and family and other writers, because that was a kind of last hurrah for that production. They just wrapped shooting the last episode two weeks ago, so this would have been a major last gathering of a lot of those people. They said they really hadn’t had a chance to have a wrap party yet, so in a sense it probably was.

The Hall H Experience

KT: Did you have the Hall H experience at all?

HJ: We went to see Heroes one morning, which was the first time, they said, a TV show had made it into Hall H. We managed to be there for Watchmen and a few of the other movies that followed it.

KT: I kind of avoided it for a while because I kept hearing that there would be incredibly long lines, and I pictured just sitting there for hours and hours and hours reading and possibly not getting into what I wanted to see anyway. So I avoided it until yesterday [Saturday], and I went to the Terminator Salvation one. I wanted really to go to the Pixar one, so I went to get in line very early, and ended up getting in on time for Terminator Salvation.

HJ: Well, for Heroes we waited for about an hour outside and then got in. Then there was a fairly long wait to get started, but then we knew that there were several things after that that we wanted to see as well.

KT: And was it full?

HJ: It was packed. But Heroes has been a kind of success story of Comic-Con. They showed the pilot there before it debuted, and Heroes is pretty desperate at this point to rekindle fan enthusiasm. Last season is largely seen as a bust. Hence their decision not to come back from the strike. They did a partial season and put it off to the fall, because the ratings were plummeting and they were getting bad buzz from fans. So they wanted to come back this year with a killer. They showed the entire opening episode, which was definitely a fan-pleaser. They had figured out what had gone wrong the first season and had put together something that was going to please. So there was lots of extended applause at key moments. It’s kind of fascinating to watch an episode of a TV show with 6500 other people.

The Exhibition Hall

KT: I only discovered the comics section today, as I was about ready to leave, because I hadn’t really been aware of which sections were devoted … I sort of thought it was all random, but obviously they do devote one big section to all the people who are selling old comic books. I suppose you could just stay in one part of the hall and never see the rest of it.

HJ: I felt I barely made a dent in the hall. The first day I didn’t quite realize how big it was, so I was just going up every aisle, and the second and third day I was going on targeted missions. But it still was just so immense that there’s no way you could see it all.

KT: And it’s SO congested.

HJ: Especially if you get to the studio side of things.

Autographs and Planning

KT: I could not figure out what was going on at the Warner Bros. exhibit, but they were constantly surrounded by lines and lines and lines of people who were obstructing the aisles around them. I guess they had people from their TV shows signing.

HJ: They seemed to. I kept stumbling into people. You wander around one corner and there’s Peter Mayhew of Chewbacca fame sitting there, and Will Frakes suddenly would pop up at another table. Neither particularly advertised. Then there were all the advertised autographed stuff. There were a lot of people there that you would know in another context.

KT: I don’t know how you would find out about all of those things in advance. I don’t think Lynda Barry was listed in the program as doing autographs, but she was at the Drawn and Quarterly booth at certain times. I missed her entirely. I got her autograph because I was sitting in the audience before her presentation and she sat down beside me.

HJ: They seemed to have a certain number of people who were there to do autographs, but then there were all these other people randomly. I guess you had to follow a particular company and maybe they posted on the Web.

KT: Yes, I was doing autographs at certain times for my book, and it was just on TheOneRing.net and The Frodo Franchise [websites]. You have to really investigate, go in with a plan.

HJ: It seems to be the case: The more you plan, the more you can get out of the experience.

KT: We were selling copies of my book at this very small booth, and I was there for an hour at different times of day on three days. I think almost everyone, if not everyone, who bought a copy came to the booth specifically to buy it. There were no impulse purchases. I don’t think people buy books at Comic-Con.

HJ: I looked at comics while I was there, but I would buy them from my dealer back in Boston or online at Amazon or My Line Comics [?]. Why I would weigh my suitcase down with comics in the age when it’s so easy to buy stuff digitally?

KT: Not new ones.

HJ: Not new ones. Collectibles, sure.

KT: Unless you have them signed.

Fan Culture hangs on at Comic-Con

HJ: Usually the cons I go to are small-scale, very intimate, you know a high number of the people who are coming. It’s fan-driven and fan-focused. This was like Creation Con on steroids!

KT: Though technically speaking, it is run by fans; there’s a committee.

HJ: It is, and they had a really bad art room with lots of cat pictures and dragon pictures and wolf pictures, which gave it a sense of fan authenticity, because they hadn’t closed out the really bad fan art, even in the midst of all the commercial takeover.

KT: Well, I missed that one.

HJ: You didn’t miss anything, other than the reaffirmation that this was still a con. There were still places and niches and corners where the fan stuff still ruled. You wouldn’t see fanzines there, but then you wouldn’t see them at most fan-run cons these days, since everything’s moved to the Web.

KT: Well, there’s Artists’ Alley, which is way over in the corner. That seems to be fans who are aspiring to be pros but haven’t really made it yet.

HJ: Well, it was a mix. I mean, you’d see Paul Chadwick there [author of “Concrete” series, published by Dark Horse Comics] or Kim Deitch [author of graphic novels such as The Boulevard of Broken Dreams and Shadowland], who were independent and weren’t necessarily going to be there with a company, but yeah, it’s definitely a lot of wannabes in some of that space.

And then fans show themselves through costumes. For all the jokes about women in Princess Leia costumes—and I saw maybe a dozen Princess Leia slave-girl outfits—it was still a way in which fans asserted their presence. There were some quite remarkable pieces of fan performance going on there. There was someone doing Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast, which had quite a spectacular Beast costume—a little more arty than one expects at a fan con.

Genre

[I mentioned having seen Focus Features’ Hamlet 2 preview.]

HJ: The role of comedy here interests me a lot. I’m always intrigued: What’re the borders of what a fan text is and what isn’t a fan text? Here comedy seems to creep into fandom in a more definitive way than I’ve seen elsewhere. So there was the focus on Hamlet 2, there was Harold and Kumar, The Big Bang Theory [TV series, 2007-08], but then just a bunch of panels on writing for sit-coms. So it’s probably just the industry’s priorities, but it’s interesting that it doesn’t extend to drama. You can imagine a lot of people there being into The Wire or The Shield or some equivalent, and it didn’t cross over in that direction.

KT: I suppose it’s what the studios think the fans want. It’s true there were a lot of comedies, and martial arts, war.

HJ: I think martial arts probably has crept into fandom pretty definitively over time. But it’s interesting to see where the boundaries are. We stumbled across one booth that had just a porn star signing her pictures, and it sort of outraged my son. Pornography isn’t fandom in his world view, but he thought nothing of going up to get wrestlers to sign autographs. Probably in any other fan con, the strong presence of wrestling performers would be out of keeping with fandom.

The Economics of It

KT: I was struck by how cheap it is, basically. How much was it for a single day pass?

HJ: Twenty-five dollars for a single day pass. It’s not bad at all for the scale of what you get. [Four-day passes are $75.]

KT: Some of the smaller tables were something like $380 for the full period, which I thought was kind of cheap. But obviously they NEED both sides of it. They need the exhibitors to attract the people and they need the people to attract the exhibitors, so keeping the cost down makes perfect sense.

HJ: The scale at which companies brought in people was also truly remarkable. I certainly have been to cons where they might have two or three performers from a show, but they brought the entire regulars of Heroes down, as well as the entire writing team. And Heroes is a large, large cast. They scarcely had time for anyone to say anything, but all lined up there on a panel, it was a pretty spectacular display. And Watchmen did pretty much the same thing. All the main characters in Watchmen were there with the director.

KT: That reminds me of the coverage that the film events and I suppose the television events, too, get in the trade press. I’m sure you read some of these articles about how, “Oh, it’s all becoming SO much Hollywood. The big media companies are coming in and taking over,” and so on. It struck me that Hall H is really kind of a world unto itself.

HJ: It is.

KT: It’s separate. You have to go out of the building and get in this line, and then you have to go out of the building when you exit. It’s quite a hike to get there if you’re around D or C in the exhibition hall. I think probably they don’t see much of the rest of the con.

HJ: It does seem largely cut off. That’s the sort of classic place where people camp. And so there’s almost an interesting tactical advantage in being one of the filler programs between the main events, if you can really maneuver into that. It’s like being right after a hit TV show or between two hit TV shows. You’re going to get exposure to people who wouldn’t otherwise. Yesterday Chuck was between Battlestar Gallactica and the Fringe panel. I’ve never see Chuck, but I wanted to see Battlestar and I wanted to see J. J. Abrams [executive producer of Lost and one episode of The Fringe], so we stuck through it. And we’ll probably give it a shot come fall as a result of being exposed to it in that way. There’s lots of things that get sandwiched in that probably get a boost off of this. Or they could hurt themselves.

KT: Bring the wrong scenes or whatever.

HJ: Wrong scenes or just the people are inarticulate. There’s certainly a range of comfort level up there.

In terms of the press coverage, the fact that Entertainment Weekly put Watchmen on its cover this week a year before the film comes out, purely on the basis of it playing at Comic-Con, says something about the publicity value of this thing.

KT: Oh, yeah, for the films there’s no doubt about its publicity value. I just think that if the big entertainment journalists plant themselves in Hall H and don’t pay a lot of attention, then you get this coverage that makes it sound as though the movies are just taking over everything.

HJ: It’s odd. It’s certainly every bit as spectacular a place to do TV as it is to do film. And comics. I couldn’t believe the betrayal I was committing in not seeing the full writers of Mad magazine in the 1960s or seeing Forrest J. Ackerman and his staff—things that were really significant to me as a kid or now. But they were competing with other things that I valued even more. So there are things that you would have killed to get to in any other context that you pass up because there’s so much going on at once. You can’t get to it all.

KT: I just get the feeling that if you at Hall H you’re at one con, and if you’re at the rest of it, you’re in a completely different world. The trades just never talk about that other stuff because it’s not really high-powered.

HJ: The question is, to what degree does that other stuff provide the context that explains what goes on in Hall H? Geek culture is integrated. Probably there are lots of people who travel between Hall H and other things, but if the reporters stay at Hall H, they won’t see the full layering of this.

The Gender Composition of the Attendees and the Industry